Abstract

Superpositions of social networks, such as communication, friendship, or trade networks, are called multiplex networks, forming the structural backbone of human societies. Novel datasets now allow quantification and exploration of multiplex networks. Here we study gender-specific differences of a multiplex network from a complete behavioral dataset of an online-game society of about 300,000 players. On the individual level females perform better economically and are less risk-taking than males. Males reciprocate friendship requests from females faster than vice versa and hesitate to reciprocate hostile actions of females. On the network level females have more communication partners, who are less connected than partners of males. We find a strong homophily effect for females and higher clustering coefficients of females in trade and attack networks. Cooperative links between males are under-represented, reflecting competition for resources among males. These results confirm quantitatively that females and males manage their social networks in substantially different ways.

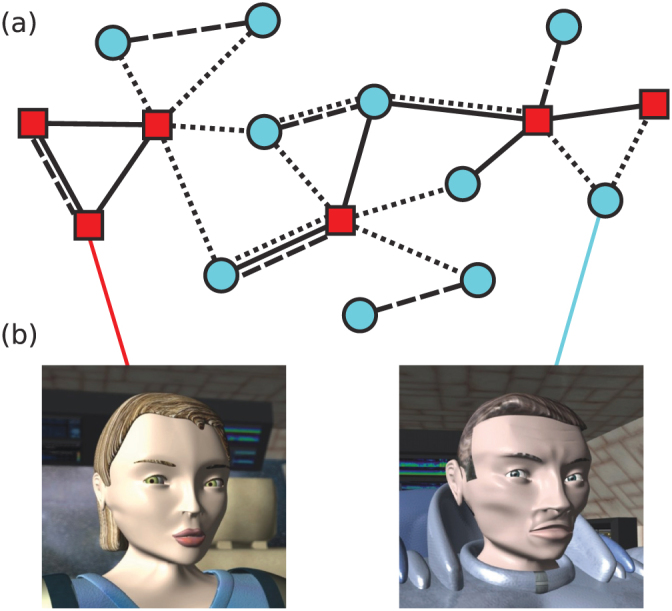

Essential to understanding the behavior of humans within their socio-economical environment is the observation that they simultaneously play different roles in various interconnected social networks, such as friendship networks, communication networks, family, or business networks. The superposition of several networks on the same set of nodes (individuals) is called a multiplex network (MPN), Fig. 1. In social networks, interactions between individuals (such as communication, trading, aggression, revenge) can be represented as links. Since these interactions can be unilateral and do not necessarily have to be reciprocated, in general the MPN consists of a set of directed, weighted and time-varying subnetworks. The MPN is a highly non-trivial, dynamical object which allows to quantify societies on a systemic level. In particular the MPN captures the co-evolving nature of societies, where on one hand actions of individuals shape and define the topological structure of the MPN, and on the other hand, where the topology of the MPN constrains and shapes the possible actions. The position of an individual within the MPN has an impact on her/his possibilities for actions in the near future and her/his state of being. The state of an individual characterizes its present situation such as its wealth, achievements, skills, number of friends, etc. The notion of the MPN conveniently allows to study the interdependencies of different social relations and in particular how they mutually influence each other through network-network interactions1.

Figure 1. Multiplex networks consist of a set of nodes connected by different types of links.

(a) In the MMOG dataset, six types of social links co-exist between players, representing their friendship or enmity status, exchange of messages, trading activity, aggressive acts (attacks), and their placing of head-money (bounties) on others as a means of punishment. (b) Each player of the MMOG Pardus chooses a male (circles) or female (squares) gender when joining the game (adapted from http://www.pardus.at).

The study of small-scale MPNs has an established tradition in the social sciences2,3,4,5, for large societies however, in general the MPN can not be observed directly due to immense data requirements. Nevertheless there are recent considerable achievements in understanding several massive social networks on a quantitative basis, such as the cell phone communication network6,7,8, features of the world-trade network9,10,11, email networks12, the network of financial debt13 and the network of financial flows14. The integration of various time-varying networks on an entire society has so-far been beyond the scope of any realistic study.

Online media have revolutionized the possibilities of measuring human behavior on societal levels and allow for the possibility of transforming the social sciences into a quantitative, experimental science15,16,17. Interactive online games provide a particularly powerful tool to quantitatively study human socio-economic multiplex data18,19. These games are usually played by thousands, sometimes even millions and offer ‘alternative lives' where players engage in different types of social interactions, such as establishing friendships and economic relations, forming of groups, alliances, parties, or performing aggressive acts like fighting or waging war20. Practically all actions of all players can be recorded at a time resolution of a second. Massive Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs) open a previously unimaginable potential for data-driven, quantitative socio-economic understanding of human societies1,20,21,22, with three obvious advantages over traditional methods: (i) Complete information on the topology of the MPNs: All topological properties of the MPN are available. The inter-dependence of the different networks in the MPN reveals the organization of the system at different levels1. (ii) Complete information about the co-evolution of the MPN with the behavior, actions and performance of individual players. Players can be grouped into different classes such as their gender so that the MPN can be studied gender-specifically. (iii) Reduced measurement bias: players are not constantly aware of their actions being recorded – the experimental setup does not influence the behavior which is often a problem in behavioral experiments23.

Humans actively influence and re-structure their local MPN. In fact a large fraction of human activity is devoted to re-arranging, managing and maintaining various social networks at the same time. In this paper we focus on genderspecific differences in managing and maintaining local MPN environments and how this correlates with performance. To identify differences in networking behavior of male and female players, we analyze complete and coherent MPN data from a MMOG society of about 300,000 players19.

There exist a few quantitative, data-driven studies on gender-specific behavior with the focus on the use of communication media, including a study on telephone usage in 317 French homes24, a large-scale Belgian mobile phone call and test message dataset25, and a gender-specific content analysis of instant messages26,27. Gender differences in online gaming is relatively unexplored, with the exception of recent work on gender roles28, the relation of gender and age group29, and gender swapping30,31,32,33, i.e. the phenomenon of playing a gender different from the biological sex.

Pardus (http://www.pardus.at) is a browser-based MMOG in a science-fiction setting, played since September 2004. MMOGs are characterized by a substantial number of users playing together online in the same virtual environment19,34. In Pardus every player owns a single, individual account which is associated with a game character. A character owns a spacecraft with a certain cargo capacity, and can roam the virtual universe, trade commodities, socialize, and do much more, usually with the motivation to gain wealth, social standing, respect, and fame in the virtual world (http://www.pardus.at/index.php?section=about). One feature of Pardus is a trading platform which provides the possibility for the production and distribution of virtual goods and services. The ‘society’ of Pardus is mainly driven by social factors such as friendship, cooperation or competition. Its gameplay is based on socializing and role-playing, with interaction between players, and with interactions between players and non-player characters19. It is important to mention that the various social networks which can be extracted from the Pardus game indeed form a MPN, in the sense that these networks are tightly related and mutually influence each other. This was systematically explored and quantified in1. For more details on Pardus, see20.

When signing up for the game the player choses to be a male or female character. The gender of a character can not be changed afterwards. The consequence of the virtual gender is that a male or female avatar is displayed during communication in the game, see Fig. 1 (b). We have no information about the biological sex of players. The possibility of freely choosing a virtual sex may lead some players to experiment with gender roles31,32,33,34. Selecting a gender different from the biological is called gender swapping which is common in online environments35. A survey on 8,694 players in the Everquest MMOG found that 15.5% are gender-swapped, 17% of the males and 10% of the females30. Similar values are reported for the virtual environment Second life (10% swapping of all, 16% of males, just 2.7% of females)36 or the World of Warcraft MMOG (23% of males, 3% of females swapping for the ‘most enjoyable’ character)37. In the Pardus game the data acquisition process aggregates both possible gender-specific behavioral effects resulting from the underlying biological sex of the players on one hand, and from their chosen online gender – regardless of sex – on the other hand.

Players can anonymously mark others as friends or enemies. Private Messages (PM) are the prevalent form of communication in the game. It is comparable to email in the real world. A PM is seen by sender and receiver only. For more details see20. Communication events, friend and enemy markings, trades, attack and bounty placements are recorded as networks: A link of type ‘communication’, ‘friend’ etc. is placed from player i to j if i has communicated with j, or has marked j as friend/enemy, etc. Friend/enemy markings exist until they are removed by players, while PM, trade, attack, and bounty networks are recorded by aggregating all actions that happened before to a given day. Friend and enemy networks are unweighted, for all others the weights correspond to the cumulative number of PMs sent, trades made, etc. The actions of communication, trading, and friend marking we consider to be positive (friendly) actions, whereas attack, enemy marking and bounty collection are negative (unfriendly). For more information on the MPN data, see SI. The legal department of the Medical University of Vienna has attested the innocuousness of the used anonymized data.

Results

Females are less risk-taking but wealthier

By economic actions such as trade, players earn virtual money in the currency of credits. Destructive, and aggressive actions such as attacking others, may result in the destruction of those players (kills), the destruction of oneself (death), or the collection of a bounty if a bounty was placed on a destroyed player's head. Players spend action points (AP) to perform all of these actions, which provides a measure for their overall activity. Players have the possibility to earn experience points through various actions or jobs, such as destroying ‘space monsters’.

In Table I we report the number of APs spent, credits and experience points earned, players killed, deaths, and bounties collected per day, averaged over all players. To compare values from males with values from females, we adopt a standard two-sample t-test, testing for the null hypothesis H0 that the two distributions have equal means, against the alternative hypothesis H1 that the means are not equal. The test is two-tailed, making no assumptions whether values from females are supposed to be larger than from males or vice versa, see Methods. It is immediately clear that females accumulate significantly more wealth (H0 rejected at 4 sigma level), i.e. credits, than males. At the same time male players experience significantly more deaths (rejection at 2 sigmas), due to more risk-taking and/or aggressive behavior. This points at a much larger engagement of females in economic, rather than destructive activities. Concerning overall activity, experience points, kills and collected bounties, female and male players perform comparably (H0 cannot be rejected).

Table 1. Quantifiable achievements of players in the game. These include spent APs, earned credits, experience points earned, players killed, deaths, bounties collected. For each player we calculate a respective daily value for these quantities, and average over them. The respective units are used as in the game (arbitrary units). The last column denotes whether the null hypothesis H0 of equal means is rejected. Females collect significantly more money (4-sigma event) and experience less deaths (2 sigmas) than males.

| Female | Male | H0 rejected | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (APs) | 2714 | 2607 | no |

| Wealth (Credits) | 14619 | 11073 | yes **** |

| Experience | 270 | 250 | no |

| Kills | 0.0055 | 0.0063 | no |

| Deaths | 0.026 | 0.030 | yes * |

| Bounties | 0.0024 | 0.0025 | no |

*p-value < 0.05, **** p-value < 0.0001

Females attract positive behavior

We now focus on action weights, i.e. how many actions of each type are initiated (out-weight) or received (in-weight) by the average female or male player. Table II, upper panel, shows the out- and in-weights for the different action types. Highly significant differences for all positive action types are observed, where females are much more active in performing actions: marking friends (null hypothesis H0 of equal means rejected at 2 sigmas), writing private messages (3 sigmas), or initiating a trade (4 sigmas). At even higher significance levels (rejection of H0 at 5 sigmas) females receive positive actions with respect to males: being marked as friend, receiving a private message, and being on the receiving end of a trade than their male co-players. For all negative action types males are both more active in initiating and receiving than females, however to a less substantial degree.

Table 2. Gender-specific number of relational actions and links. Upper panel: Out-weights (actions initiated or messages sent) and in-weights (actions/markings/messages received). For each player we calculate a daily value for the number of actions performed and received and average them. Male values are presented as in Table I. For values with stars the null hypothesis H0 of equal means is rejected. Females mark significantly more friends (H0 rejected at 2 sigmas) and are marked themselves much more as friend (5 sigmas). They send and receive significantly more PMs (3 and 5 sigmas, respectively), and perform and receive significantly more trades (4 and 5 sigmas). Females perform less attacks than males (2 standard deviations). Lower panel: Homophily and heterophily: Over- and under-represenation, as measured by Z-scores (See SI), of directed link types of the six networks at day 856. Each real network is compared to 1,000 surrogate networks where the gender of nodes is randomly reshuffled. The most significant over-represented link types are female-to-female trades and communication (PMs), followed by male-to-female trades and PMs. Female-to-male trades and PMs are over-represented, however not as drastically. Highly under-represented are male-to-male PMs and trades. Negative links show neither substantive over- or under-representation.

| Positive links | Negative links | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friends | PMs | Trades | Enemies | Attacks | Bounties | |

| Action weights | ||||||

| Initiated M | 0.026 | 0.60 | 0.100 | 0.029 | 0.20 | 0.009 |

| Initiated F | 0.028* | 0.74** | 0.124*** | 0.027 | 0.16* | 0.009 |

| Received M | 0.022 | 0.45 | 0.066 | 0.036 | 0.116 | 0.0084 |

| Received F | 0.027**** | 0.61**** | 0.086**** | 0.032 | 0.109 | 0.0074 |

| Homophily | ||||||

| FF | 0.6 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 0.6 | −0.4 | −0.6 |

| MM | 0.4 | −2.3 | −2.4 | −0.6 | 1.0 | −0.2 |

| FM | −0.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | −0.3 | −1.7 | 0.4 |

| MF | −0.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | −0.2 |

*p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001, **** p-value < 0.0001

Females show homophily, males are heterophiles

Homophily is the tendency of individuals to associate and link with similar others3. In our case we test for linkings between individuals of the same gender. A straightforward way to measure homophily in the mutiplex data is to compare the numbers of directed links between all gender-combinations in all networks (MM, MF, FM, FF) to the corresponding numbers surrogate networks where the gender of nodes is randomized. Table II, lower panel, shows the result of this comparison. Positive and negative Z-scores (see SI) denote the number of standard deviations by which a link type is over- or under-represented, with respect to the randomized case. To measure statistical significance of differences between different combinations of genders, we compare each real network to 1,000 surrogate networks where the gender of the nodes was randomly reshuffled, leaving the topology of the network intact. Clearly, female-to-female trading and communication are the most significantly overrepresented link types, with a Z-score of approximately 4 sigmas. Male-to-female trades (Z = 2.7) and communication (Z = 2.7) are also strongly over-represented, whereas the opposite, female-to-male trades and PMs is much less substantial (Z = 1.4 and 1.6, respectively). Male-to-male trades and communication are highly under-represented (Z = −2.3 for both cases). Negative link types show no significant tendency in either direction.

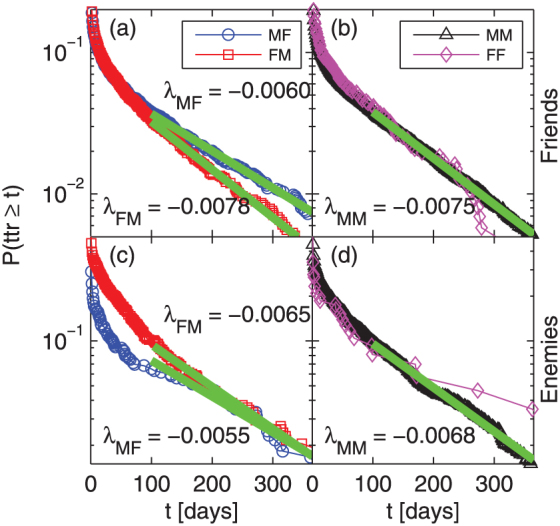

Males respond fast (slow) to female friendship (enmity) initiatives

We measure the time (days) it takes for individuals to reciprocate an action of a given type. For all pairs (i, j) where an action was reciprocated, the time-to-reciprocate (ttr) is the number of days from initial marking to reciprocation. In Fig. 2 (a) and (b) we show the cumulative distribution functions for the time-to-reciprocate for friendship and enmity links, for the four possible gender permutations: MM, FF, MF, FM. Here the first letter denotes the gender of the individual who placed the initiating link, the second letter denotes the gender of the one who reciprocated. Reciprocation time probabilities follow a sub-exponential decrease for about the first 30 days after a link was initiated, beyond which distributions become approximately exponential, P(ttr ≥ t) ~ e−λt. The decay rate λ for friendship reciprocation with male initiation followed by female reciprocation is λMF ≈ −0.0060. For female initiation and male reciprocation it is λFM ≈ −0.0078. The MM rate lies between, close to the FM case, λMM ≈ −0.0075, (b). Correspondingly, the half-life for MF reciprocation is about 116, for FM it is only 89 days. The situation changes for the enemy links. Here a big difference is found for the short times: within the first 150 days of an enemy marking males reciprocate much less than females. The approximate exponential tails have a λFM ≈ −0.0065 and λMF ≈ −0.0055, respectively. The ttr-distributions for the other actions are found in the SI.

Figure 2. Distributions of time-to-respond for different genders.

(a) Cumulative probability distributions for the time-to-respond (ttr) for females to reciprocate a friendship link, given the initiator was male (MF), and vice versa (FM). Probabilities fall sub-exponentially in the first 30 days, later exponentially, P(ttr ≥ t) ~ e−λt with long-time decay rates λ depending on gender pairs: Males are much faster to reciprocate female friendship initiatives (λFM = −0.0078) than the other way round (λMF = −0.0060). (b) Situation for equal sex reciprocation MM, and FF. Here reciprocation decay times are in between the MF and FM case. (c) Cumulative ttr distributions for enemy links. For enemy markings, males are considerably slower to reciprocate within the first 180 days if the initiator was a female than vice versa. (d) Situation for equal sex reciprocation of enemy links. Fit ranges are 100 to 365 days, fits of FF curves were not feasible.

Gender differences in networking

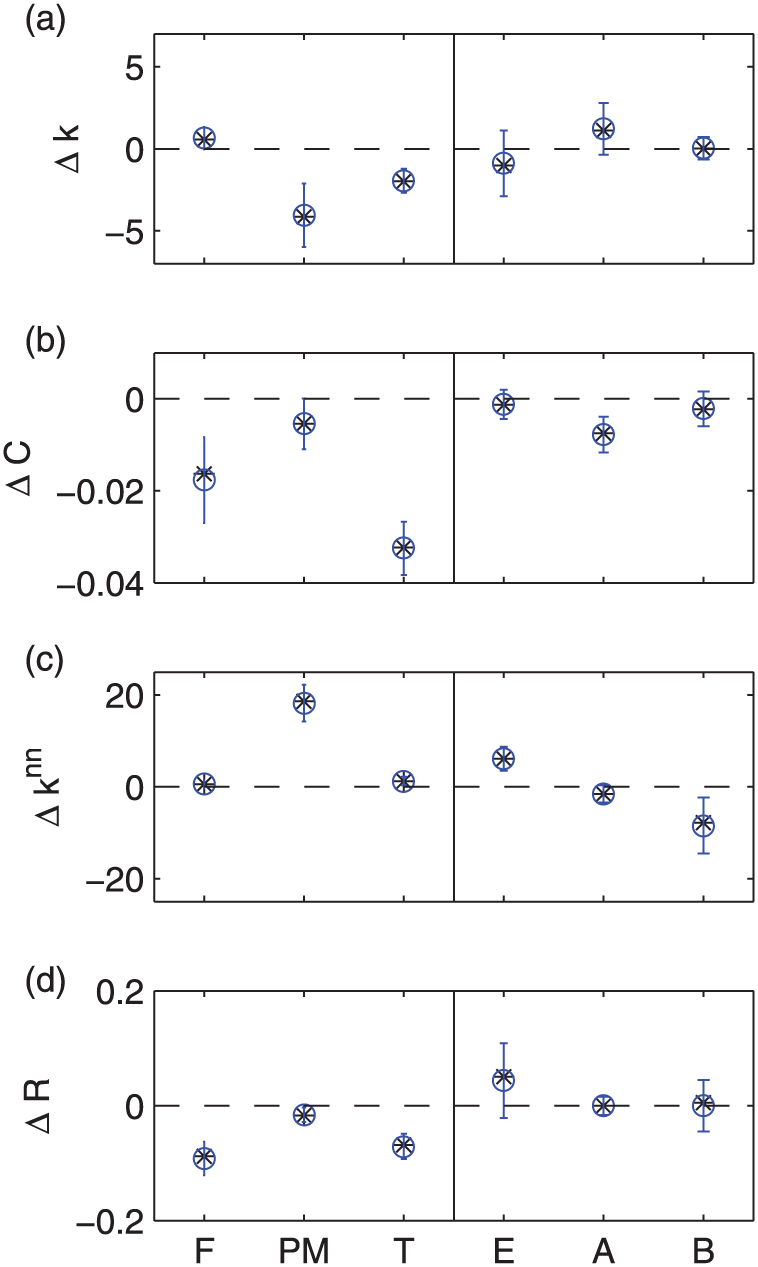

Figure 3 shows gender differences in four network properties as observed on day 856, illustrating the clear evidence that males and females structure their local MPNs in different ways. We compute the average degree  , the clustering coefficient C, and the average neighbour degree knn (see SI) independently for the 8 male control groups and the female group, see Methods. We then subtract the value for the female group from the average of the 8 control groups. This difference is indicated in Fig. 3 by the letter Δ. Errorbars indicate the standard deviations of the means of the control groups. A statistical t-test supports these results by significant rejection of the equal-means hypothesis, see Methods and SI.

, the clustering coefficient C, and the average neighbour degree knn (see SI) independently for the 8 male control groups and the female group, see Methods. We then subtract the value for the female group from the average of the 8 control groups. This difference is indicated in Fig. 3 by the letter Δ. Errorbars indicate the standard deviations of the means of the control groups. A statistical t-test supports these results by significant rejection of the equal-means hypothesis, see Methods and SI.

Figure 3. Differences of network properties between male and female players (M − F) on the last day 856.

(a) average degree  , (b) clustering coefficient C, (c) average neighbour degree

, (b) clustering coefficient C, (c) average neighbour degree  . Females have higher average degrees in PM and trade networks, as well as a higher clustering coefficient in trades, but considerably lower

. Females have higher average degrees in PM and trade networks, as well as a higher clustering coefficient in trades, but considerably lower  for PMs. (d) reciprocity R between male-male and female-female links on the last day 856. Females are substantially more reciprocal in friendships and trades. Errorbars denote the standard deviations of the network measures obtained from the 8 male control groups (each of the size of the female group), illustrating the substantial differences. A statistical t-test supports these results by significant rejection of the equal means hypothesis. For definitions see Methods.

for PMs. (d) reciprocity R between male-male and female-female links on the last day 856. Females are substantially more reciprocal in friendships and trades. Errorbars denote the standard deviations of the network measures obtained from the 8 male control groups (each of the size of the female group), illustrating the substantial differences. A statistical t-test supports these results by significant rejection of the equal means hypothesis. For definitions see Methods.

Females have more communication partners

As seen in Fig. 3 (a) females have about 15% more communication and trading partners (degree) than males.

Females organize in clusters

Female trading networks show a clustering coefficient (see SI) that is about 25% higher than the one of males, Fig. 3 (b). This means that females tend to trade with people who trade among themselves. Also the clustering of female friendship networks is significantly higher than those of males, showing a preference for stability38 in local networks. Surprisingly, also in the case of attacks females are more likely to attack people who are in conflict with each other than males.

Males prefer well connected communication partners

From Fig. 3 (c) we learn that the communication partners of males have more communication partners than the communication partners of females (for the neighbour degree knn, see SI). The same tendency is seen for the male enmity networks, meaning that the typical enemy of a male player has more enemies than the typical enemy of a female. In relative terms, both effects are in the 10% range.

Females reciprocate friendships

Females invest more effort in reciprocating links. Fig. 3 (d) reports that females reciprocate 20% more friendship and trading links than their male counterparts. For communication and negative links there are no substantial gender differences observable. For the measure ΔR we considered male-male and female-female links. More details are found in the SI.

Discussion

We quantitatively studied gender-specific behavior and network organization in a society of humans engaged in a virtual world of an online game. We find clear differences of how females and males structure and manage their local MPNs. Females show a significantly higher average degree  in their communication networks, however, the communication partners of females have a significantly lower average degree than those of males, i.e. females have more communication partners, while males tend to have better connected ones. The positive MPNs of females are far more clustered than those of males. The combination of higher clustering coefficients with lower average neighbour degrees knn indicates that females manage their local MPNs to be tighter and more compact. On the behavioral level females are more engaged in the reciprocation of their positive relations, again signaling that they invest more in stable and secure networks. This is also reflected in their less risk-taking behavior and a better overall economic performance in the game.

in their communication networks, however, the communication partners of females have a significantly lower average degree than those of males, i.e. females have more communication partners, while males tend to have better connected ones. The positive MPNs of females are far more clustered than those of males. The combination of higher clustering coefficients with lower average neighbour degrees knn indicates that females manage their local MPNs to be tighter and more compact. On the behavioral level females are more engaged in the reciprocation of their positive relations, again signaling that they invest more in stable and secure networks. This is also reflected in their less risk-taking behavior and a better overall economic performance in the game.

So far only a limited body of data-driven works on gender-specific network organization exists. A particular exciting one is a study on the use of classic communication media (telephone)24, where it was found that women call more frequently and spend about twice as much time on the telephone than men. We find a comparable effect. Female players send about 25% more messages (0.74 per day) than males (0.60 per day). In24 a gender homophily effect3 was found for both sexes. We find a comparable effect for females only where female-to-female links in the communication network are strongly over-represented with respect to pure chance. In contrast to24 we find that links between pairs of males are less likely than expected by chance. This tendency might be caused by the male-dominated game environment in which females may be treated far better than males, which is a known phenomenon30, and therefore also receive more messages. Inter-gender response time distributions reveal that females respond much slower to male friendship initiatives, than males do to female ones. We find clear evidence that females ‘attract’ positive behavior to a much higher degree than males. It is important to note that players have neither direct information about – nor influence on – the links of their neighbours (except for their own). Therefore, the observed differences in network patterns such as clustering coefficients and average neighbour degree, can not be explained through social group dynamics, such as e.g. in the friendship dynamics in Facebook, but instead constitute strong direct evidence for biological gender-specific differences in networking behavior.

The direct implications of the presented work to real societies has to be discussed with some care. First, it is not a priory obvious how representative MMOG societies are for real human societies, and second, how much does gender swapping influence the results? The only way to determine to what extent MMOGs are good models for ‘real’ society is the direct comparison of the MPNs in games with those observable in the ‘real’ world. Previous results on the same Pardus dataset show amazingly good agreements20 between statistical properties of the communication network of players and mobile phone networks6,8. Also in20 the evolution of network measures and of network growth patterns, including network densification, was shown to strongly overlap with data from ‘real-world’ societies39,40. In further work1 additional equivalent results have been found in the study of sociological hypotheses on structural balance41. We have not explicitly conducted a survey on the extent of gender swapping in Pardus, however we have reason to believe that we are in the same ballpark as comparable MMOGs35, meaning that we expect about 15% of players whose avatar has a different gender than their biological player. For all of our conclusions this fraction can be regarded as marginal.

In conclusion, the substantial gender effects in different types of networking and reciprocation behavior that we find in the online world of Pardus, suggest two main implications. First, if we assume our findings to hold in online environments in general and if the majority of players choose their online gender in accordance with their biological sex, this implies that we can find and explore traces of biological human behavior in online environments. As previous studies on mobility42 or social organization hypotheses1,20 have shown, the type of medium and actual physical contact are of limited relevance for a wide range of social behavior. Our results imply an impact on the understanding of relation-formation between individuals of different and the same genders, and thus eventually might help to understand reproductive strategies behind the behavior of finding and competing for mating partners43. Second, our setup demonstrates that online media increasingly blur gender roles and can render the biological sex of social actors less important. Without tangible signals, representing the behavior of a male or female may be more important here than actually having male or female sex. Lacking information on sex does not enable us to disentangle sex–gender effects: Does a male acting as a female behave differently from a female who chooses a female online persona? We do not know – further data and studies on gender-specific offline–online behavior are needed to answer these specific details. Nevertheless, our results could have immediate applications both offline and online, in particular in control of gender-specific information spreading, in marketing, or for smooth implementation of online social networks and dating sites44.

Methods

The social multiplex network data

For the MPN we considered all players of the Artemis universe who played within the time interval from day 1 to day 856 and who performed at least one communication event, a trade, an attack, or a bounty request, or who were involved in at least one friendship or enmity relation on day 856 (the trade relation studied here is all ship-to-ship trades, reflecting the business relations in which trust is important – this is slightly different to trade networks constructed from ship-to-building trades which can be of more impersonal nature1,20). We discard all players who existed for less than 1 day. The communication-, trade-, attack-, and bounty networks were accumulated over time, enmity and friend networks were taken as snapshots of day 856. This leads to 23,872 players (nodes) in the MPN with 21,264 males and 2,608 females. For the time-to-respond calculations we used also all players involved in reciprocated friendship and enmity markings over the 856 days, increasing the total number of players to 34,210 (30,607 males and 3,603 females). For the calculations of player achievements, we used those 6,548 players who played on day 856.

Control groups

At any time, there are roughly 8 to 9 times more male than female players. For highlighting substantial gender differences, we randomly divided the set of male players into 8 non-overlapping control groups, each of the size of the female group (3,603). We compute mean and standard deviation of these 8 control samples for comparing network-and performance measures in Fig. 3 and in Supplementary Table I. Following the central limit theorem, with a large enough sample size the standard deviation of the sample means follows a normal distribution regardless of the shape of the parent population. Since the number of samples here is very low (8), the deviations of the sample means are to be treated with care. For rigorous statistical testing however, we use a two-sample t-test, see below.

Statistical technique for hypothesis testing

For directly comparing values between males and females, we use a standard two-sample t-test for testing the null hypothesis H0 that two distributions have equal means, against the alternative hypothesis H1 that the means are not equal. We assume equal variances and use two tails, i.e. no preference of testing for one specific gender to have larger values than the other. Thus the t-test computes a pooled standard deviation

where nm, nf are the sizes of male and female values considered, and varm, varf their variances, respectively. The test statistic is then given by

where  and

and  denote the means of the male and female values.

denote the means of the male and female values.

Author Contributions

All the authors have equally contributed to the design of the study, to the analysis and interpretation of the results and to the preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the Austrian Science Fund FWF P23378. We thank Benedikt Fuchs for assistance in data analysis, and Bernat Corominas-Murtra for stimulating discussions.

Footnotes

Michael Szell owns stock in Bayer and Szell OG, the company that owns and maintains Pardus.

References

- Szell M., Lambiotte R. & Thurner S. Multirelational organization of large-scale social networks in an online world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 13636–13641 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman S. & Faust K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications (Cambridge University Press, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M., Smith-Lovin L. & Cook J. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology 415–444 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle B., Faust K., Rindfuss R. & Kaneda T. Networks and contexts: Variation in the structure of social ties. American Journal of Sociology 112, 1495–1533 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Padgett J. & Ansell C. Robust action and the rise of the Medici, 1400–1434. American Journal of Sociology 1259–1319 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Onnela J. et al. Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 7332 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onnela J. et al. Analysis of a large-scale weighted network of one-to-one human communication. New Journal of Physics 9, 179 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Lambiotte R. et al. Geographical dispersal of mobile communication networks. Physica A 387, 5317–5325 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo C. & Hausmann R. The building blocks of economic complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 10570–10575 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo C., Klinger B., Barabási A.-L. & Hausmann R. The product space conditions the development of nations. Science 317, 482 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimek P., Hausmann R. & Thurner S. Empirical confirmation of creative destruction from world trade data. Arxiv preprint arXiv: 1112.2984 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M., Forrest S. & Balthrop J. Email networks and the spread of computer viruses. Physical Review E 66, 035101 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss M., Elsinger H., Summer M. & Thurner S. Network topology of the interbank market. Quantitative Finance 4, 677–684 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakopoulos F., Thurner S., Puhr C. & Schmitz S. Network and eigenvalue analysis of financial transaction networks. The European Physical Journal B 71, 523–531 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Lazer D. et al. Computational social science. Science 323, 721 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K., Kaufman J., Gonzalez M., Wimmer A. & Christakis N. Tastes, ties, and time: A new social network dataset using Facebook.com. Social Networks 30, 330–342 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Thurner S., Szell M. & Sinatra R. Emergence of good conduct, scaling and Zipf laws in human behavioral sequences in an online worlds. PLoS ONE 7, e29796 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge W. The scientific research potential of virtual worlds. Science 317, 472 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castronova E. Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Szell M. & Thurner S. Measuring social dynamics in a massive multiplayer online game. Social Networks 32, 313–329 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Castronova E. On the research value of large games. Games and Culture 1, 163–186 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. et al. Human group formation in online guilds and offline gangs driven by a common team dynamic. Physical Review E 79, 66117 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J. et al. “Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 28, 795–815 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoreda Z. & Licoppe C. Gender-specific use of the domestic telephone. Social psychology quarterly 238–252 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Stoica A., Smoreda Z., Prieur C. & Guillaume J. Age, gender and communication networks. In: NetMob - Analysis of Mobile Phone Networks 2010 communication proposal (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fox A., Bukatko D., Hallahan M. & Crawford M. The medium makes a difference: Gender similarities and differences in instant messaging. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 26, 389 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Baron N. See you online: Gender issues in college student use of instant messaging. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 23, 397–423 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Williams D., Consalvo M., Caplan S. & Yee N. Looking for gender: Gender roles and behaviors among online gamers. Journal of communication 59, 700–725 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M., Davies M. & Chappell D. Online computer gaming: a comparison of adolescent and adult gamers. Journal of adolescence 27, 87–96 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M., Davies M. & Chappell D. Breaking the stereotype: The case of online gaming. Cyber Psychology & Behavior 6, 81–91 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckman A. Gender swapping on the internet. In Proceedings of the International Networking Conference (San Francisco, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Danet B. Text as mask: Gender, play and performance on the internet. Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Communication and Community 129–158 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Hussain Z. & Griffiths M. Gender swapping and socializing in cyberspace: An exploratory study. Cyber Psychology & Behavior 11, 47–53 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartle R. Designing Virtual Worlds (New Riders, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Grosman K. An exploratory study of gender swapping and gender identity in “Second Life”. Ph.D. thesis, The Wright Institute (2010). [Google Scholar]

- De Nood D. & Attema J. Second life: The second life of virtual reality. The Hague, EPN-Electronic Highway Platform 1 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Yee N. & Bailenson J. The proteus effect: The effect of transformed self-representation on behavior. Human communication research 33, 271–290 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter M. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78, 1360–1380 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Leskovec J., Kleinberg J. & Faloutsos C. Graph evolution: Densification and shrinking diameters. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data (TKDD) 1 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Leskovec J., Backstrom L., Kumar R. & Tomkins A. Microscopic evolution of social networks. In Proceeding of the 14th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, 462–470 (ACM, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Leskovec J., Huttenlocher D. & Kleinberg J. Signed networks in social media. Proc. 28th CHI (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Szell M., Sinatra R., Petri G., Thurner S. & Latora V. Understanding mobility in a social petri dish. Scientific Reports 2, 457 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palchykov V., Kaski K., Kertesz J., Barabasi A.-L. & Dunbar R. Sex differences in intimate relationships. Scientific Reports 2, 370 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingol H. & Basar O. Asymmetries of Men and Women in Selecting Partner. arXiv: 1211.1035 (2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information