Abstract

Bile acid sequestrants are nonabsorbable resins designed to treat hypercholesterolemia by preventing ileal uptake of bile acids, thus increasing catabolism of cholesterol into bile acids. However, sequestrants also improve hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia through less characterized metabolic and molecular mechanisms. Here, we demonstrate that the bile acid sequestrant, colesevelam, significantly reduced hepatic glucose production by suppressing hepatic glycogenolysis in diet-induced obese mice and that this was partially mediated by activation of the G protein-coupled bile acid receptor TGR5 and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) release. A GLP-1 receptor antagonist blocked suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis and blunted but did not eliminate the effect of colesevelam on glycemia. The ability of colesevelam to induce GLP-1, lower glycemia, and spare hepatic glycogen content was compromised in mice lacking TGR5. In vitro assays revealed that bile acid activation of TGR5 initiates a prolonged cAMP signaling cascade and that this signaling was maintained even when the bile acid was complexed to colesevelam. Intestinal TGR5 was most abundantly expressed in the colon, and rectal administration of a colesevelam/bile acid complex was sufficient to induce portal GLP-1 concentration but did not activate the nuclear bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor (FXR). The beneficial effects of colesevelam on cholesterol metabolism were mediated by FXR and were independent of TGR5/GLP-1. We conclude that colesevelam administration functions through a dual mechanism, which includes TGR5/GLP-1-dependent suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis and FXR-dependent cholesterol reduction.

Keywords: bile acids, glucagon-like peptide-1, TGR5, diabetes-induced obesity, FGF-15, FXR

bile acid sequestrants are orally administered nonabsorbable resins designed to treat hypercholesterolemia (23) but that have unexpected beneficial effects on glycemia in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (17). This observation has been confirmed in multiple human studies, animal models, and with a variety of different bile acid binding resins (reviewed in Ref. 41). Colesevelam is a bile acid sequestrant used to treat T2DM, but the mechanisms by which it and other sequestrants act on glucose metabolism are incompletely understood. Inasmuch as colesevelam passes through the digestive track unaltered, its efficacy on both cholesterol and glucose metabolism are thought to originate from its high bile acid-binding affinity.

Bile acids are amphipathic molecules synthesized in liver, stored in the gallbladder, and secreted into the small intestine to facilitate dietary lipid absorption (48). Ileal bile acid reabsorption and uptake by the liver is nearly quantitative and exquisitely regulated. Bile acids activate receptors in the intestine, including the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a member of the nuclear receptor family of ligand-activated transcription factors. Activation of FXR in the small intestine induces the expression and release of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 15/19 (22). FGF15/19 activates the FGFR4 receptor in liver and represses transcription of Cyp7a1 (22), a critical enzyme in the synthesis of bile acids from cholesterol. Sequestrants, like colesevelam, bind bile acids in the small intestine and prevent the FXR-dependent repression of bile acid synthesis (20), resulting in clearance of cholesterol as bile acids.

Bile acids also activate TGR5 (also known as GPR131), a plasma membrane G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) (53). In general, TGR5 activation invokes several beneficial metabolic effects including increased energy expenditure in skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissue, and activation of TGR5 in the intestine induces secretion of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) from intestinal L cells (43). The putative effects of GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) activation optimize insulin secretion, reduce glucagon secretion, and improve insulin sensitivity in liver and peripheral tissues (14). Sequestrant treatments are associated with altered levels of gut hormones (4, 19, 36, 50), including a rise in GLP-1 (4, 19, 50), which appears to require TGR5 activation (19).

The metabolic mechanism of improved glucose homeostasis during sequestrant treatment has been attributed to increased energy expenditure (56), improved glucose disposal (46), and reduced glucose production (4). Humans treated with colesevelam have reduced rates of glycogenolysis (4), a pathway partly mediated by GLP-1 (1), and a contributor to glycemic dysregulation during insulin resistance (2). We therefore investigated the role of TGR5-dependent GLP-1 action in effects of colesevelam on liver glycogen metabolism in diet-induced obese (DIO) mice. TGR5 and GLP-1 were essential for colesevelam to suppress hepatic glycogenolysis and glucose production and partially required for its glucose-lowering effects. However, the activation of TGR5/GLP-1 by colesevelam was totally dispensable for improved cholesterol metabolism, which was mediated by FXR deactivation. Thus, the unique beneficial actions of sequestrants on cholesterol and glucose metabolism are mediated by multiple pharmacological targets, including FXR suppression and TGR5/GLP-1 activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal experiments.

FXR (51) and TGR5 knockout (KO) mice (54) were generated as described previously and were backcrossed at least 10 generations to a pure C57Bl/6 genetic background. Male WT mice (C57Bl/6J; Jackson Laboratories), knockout mice, and control mice were housed under a light/dark cycle of 12 h (6 AM to 6 PM). Mice were fed standard chow (Teklad Global 2016 diet, Harlan Laboratories) containing 4% fat or 60% high-fat diet (HFD) (Research Diets, D12492i) ad libitum as indicated. For colesevelam HCl (Col) treatment in WT mice, DIO mice on the 60% HFD for 11–13 wk were ordered from Jackson laboratories and maintained on the 60% HFD until mice were 15 wk old. Mice were then individually caged and maintained on the 60% HFD or provided the HFD mixed with 2% colesevelam (Daiichi Sankyo) ad libitum for 7 days. Mice were ad libitum fed (chow or HFD) and killed between 9 AM and 11 AM for tissue and blood collection unless otherwise noted. Glucose tolerance tests (GTT) were performed in mice fasted overnight (5 PM-9 AM) and intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 2 g/kg d-glucose (Sigma) with tail blood collected at the indicated times. Tracer infusions and rectal administrations were performed after a brief 4-h morning fast to minimize active nutrient absorption without depleting hepatic glycogen (6). All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists and antagonists were administered as previously described (12, 30). Briefly, synthetic exendin-4 (Ex-4) (Anaspec,USA) and exendin-(9–39) (Ex-9) (Anaspec,USA) were dissolved in saline and administered i.p. twice daily (at 9 AM and 6 PM) at a dose of 0.1 μg/g body wt, and 0.2 μg/g body wt, respectively, for 7 days. Measurement of portal GLP-1 was performed on 250 μl of portal blood collected under isofluorane anesthesia by catheterization of the portal vein and immediately mixed with a DPP-IV inhibitor (Millipore) per the manufacturers' instructions. The remaining blood was collected and placed in a separate EDTA-tube for analysis of additional plasma factors.

Stable isotope tracer experiments.

In vivo hepatic glucose production was measured in mice with minor modifications of previously described experiments (6). Mice were fitted with a chronic jugular vein catheter and allowed to recover for 1 wk. Food was removed from the cages in the morning, and 4 h later [U-13C]glucose was infused for 90 min. The fractional enrichment of tail vein glucose was determined by GC-MS (52). Turnover was determined from the precursor product relationship and infusion rates as previously described (6).

Livers from ad libitum fed DIO mice fed a HFD or HFD + Col were isolated and perfused for 60 min with a nonrecirculating buffer at 8 ml/min as previously described. The perfusate contained a mixture of substrates and 3% deuterated water as previously described (45). Relative rates of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis were determined from the relative enrichments of effluent glucose H2 and H5 as described by Landau and adapted to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis (7, 32). Absolute hepatic glucose output was determined by assaying the effluent perfusate for glucose. Absolute rates of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis were determined by multiplying relative flux and hepatic glucose output (45).

In vivo cholesterol synthesis.

Two days after the initiation of colesevelam treatment, mice were administered a bolus injection of saline D2O (0.9% saline in 99% D2O) equal to 28 μl/g body wt and subsequently maintained with 6% D2O in the drinking water. After 7 days, mice were euthanized by decapitation, and livers were collected and immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Liver lipid components were extracted and purified. Deuterium incorporation into the C18 methyl position of cholesterol was determined by 2H NMR. Fractional synthesis was calculated as 2H enrichment in position C18 divided by body water enrichment. Absolute cholesterol synthesis was evaluated as the product of the fractional synthesis and tissue cholesterol content divided by the D2O exposure time (4 days).

In vitro TGR5-BRET assay.

For real-time measurement of cAMP responses in HEK293 cells, we generated a HEK cell line that stably expressed the cAMP bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) sensor, CAMYEL (25), and the human TGR5 receptor (TGR5-BRET cells). Functionality of the TGR5 receptor was assessed in the cell lines stably expressing the receptor by testing cAMP production in response to stimulation with bile acids. Adherent cells were plated in 96-well solid-white tissue culture plates (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) at a density of 40,000–60,000 cells per well the day before assays. The BRET assay was carried out with a POLARstar Optima plate reader from BMG LabTech. Emission signals from Renilla luciferase and YFP were measured simultaneously using a BRET1 filter set (475-30/535-30). All determinations were carried out in triplicate and all experiments conducted at least two times.

Intracellular cAMP responses to isoproterenol or bile acid treatment [cholic acid (CA), taurocholic acid (TCA), glycocholic acid (GCA), chenoxycholic acid (CDCA), taurine chenoxycholic acid (TCDCA), glycine chenoxycholic acid (GCDCA)], (all bile acids were purchased from Sigma) were assessed as previously described (25, 26). To generate a Col/BA complex, Colesevelam was hydrated in simulated intestinal fluid as previously described (18). A sample (400 μl) of 5 mg/ml Colesevelam (the maximum concentration determined not to disrupt the BRET signal) was incubated with 400 μl of 100 mM TCA and 10 μM oleic acid for 45 min. Addition of oleic acid with bile acid sequestrants improves bile acid retention on the resin (5). Following incubation, colesevelam incubated with bile acids was spun down at 2,000 rpm, and the supernatant was collected and the pellet washed. Washing of the pellet was performed twice, and the pellet, supernatant, and washes were individually treated to the TGR5-BRET cells and accessed for cAMP response. By the second wash step, BA in the wash was minimal when assayed on the TGR5-BRET cells (data not shown). These results were confirmed using radiolabeled bile acid (14C-TCA) (American Radiolabel), which indicated that 55% of the total bile acid remained on the resin following incubation and wash steps (data not shown).

Rectal administration of bile acids.

Following a 4-h morning fast, 300 μl of vehicle, 10 mM TCA (Sigma), or INT-777 (30 mg/kg) (a kind gift from Intercept Pharmaceuticals) was rectally injected. After 40 min, portal blood (250 μl) was collected as described above. Ileum and colon were collected and immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for gene expression analysis.

Gene expression analysis-quantitative real-time PCR.

Mice were euthanized by decapitation, unless otherwise specified, and tissues were isolated and immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Gene expression analysis was performed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) as previously described (45).

Metabolic parameters.

Plasma glucose, insulin, cholesterol, and glucagon levels were measured as previously described (44). GLP-1 concentration was measured in portal blood and collected as described above, using the Millipore Elisa kit (EGLP-35K) according to manufacturer's instructions. Hepatic cholesterol was extracted and analyzed as previously described (27). Body composition was determined using a Bruker Minispec mq10 NMR.

Hepatic glycogen content was determined by weighing 100 mg of liver sample into a prechilled 15-ml sterile tube and then homogenizing it for 30 s in 1 ml of 30% KOH. Homogenized tissue was boiled for 15 min and then centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min. After centrifugation, 75 μl of homogenate was spotted onto Whatman Grade 3 (cat no. 1003–323) filter disks and allowed to dry overnight in a scintillation vial. Filters were then washed once in cold (4°C) 70% ethanol by gentle shaking for 30 min, followed by two additional washes with room temperature 70% ethanol for 15 min each. Disks were then briefly rinsed with acetone and allowed to dry overnight. Once dry, filters were incubated in 2 ml of amyloglucosidase reaction mix [0.2 mg/ml amyloglucosidase (Sigma, cat. no. A7420) in 50 mM NaOAc pH 4.8] at 37°C for 90 min, mixing periodically. Samples were then assayed for glucose using the Wako Autokit glucose assay, and glycogen content was calculated as milligrams of glucose per 100 mg liver.

Statistical analyses.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical differences were analyzed using ANOVA for multiple groups or an unpaired t-test between two groups. Means were considered significantly different at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Colesevelam treatment improves the metabolic profile of DIO mice.

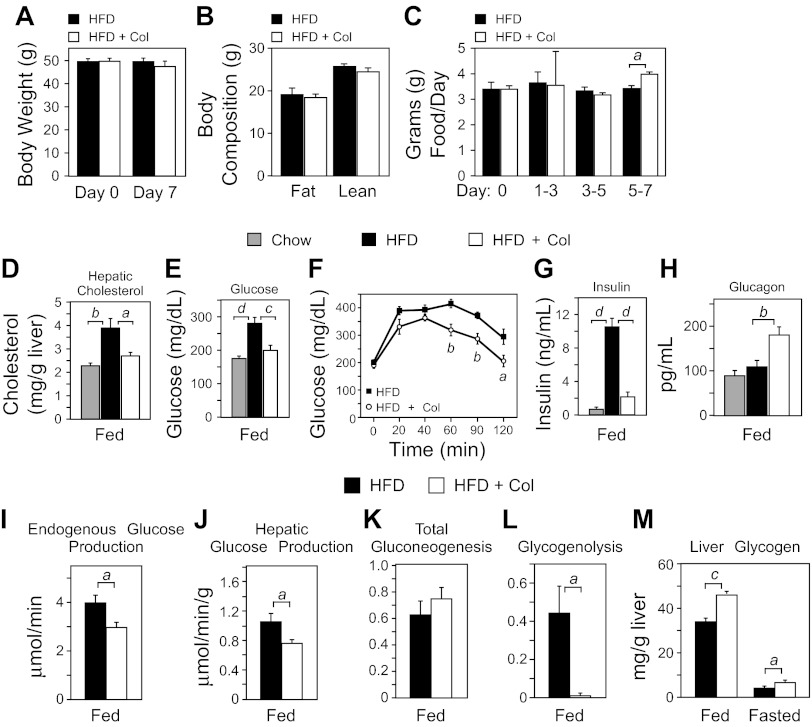

Mice were provided a 60% HFD for 15 wk to induce obesity followed by 7 days of colesevelam treatment. Colesevelam treatment did not significantly alter body weight (Fig. 1A) or composition (Fig. 1B). Food intake was unaffected until day 5 when it increased slightly (Fig. 1C). As expected, colesevelam treatment normalized hepatic cholesterol (Fig. 1D) and plasma glucose levels (Fig. 1E) and significantly reduced glucose excursion during a GTT (Fig. 1F). Colesevelam treatment also reduced hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 1G) but caused an unexpected rise in plasma glucagon (Fig. 1H). Hepatic glucagon receptor mRNA expression was not different between HFD mice and HFD mice administered colesevelam (HFD + Col) (data not shown). Together, these data confirm that colesevelam treatment in DIO mice provokes the favorable changes in cholesterol and glucose homeostasis observed in humans (17, 41).

Fig. 1.

Colesevelam modulates hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. A–M: wild-type (WT) mice were fed a chow diet or a high-fat diet (HFD) for 15 wk and treated with or without colesevelam HCl (HFD + Col) for 7 days. A: body weight. B: body mass composition. C: food intake. D: hepatic cholesterol. E: plasma glucose. F: intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (2 g/kg). G: plasma insulin. H: plasma glucagon. I: in vivo endogenous glucose production in awake and unrestrained HFD or HFD + Col mice following a brief 4-h morning fast was determined by GC-MS analysis of tracer dilution after steady-state infusion of [U-13C]glucose. J–L: sources of glucose production were determined by the deuterated water method and 2H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in isolated perfused livers from fed WT DIO mice on a HFD for 15 wk treated with and without HFD + Col for 7 days. M: hepatic glycogen content in fed and 12-h fasted (9 PM to 9 AM) HFD and HFD + Col mice. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 6–7). The presence of different lowercase letters indicates statistical significance (aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; cP < 0.005; and dP < 0.001 vs. control).

Colesevelam treatment reduces hepatic glucose production and suppresses glycogenolysis.

Endogenous glucose production contributes to hyperglycemia during type 2 diabetes (3), so we measured basal glucose turnover following a 4-h morning fast and found that it was decreased by colesevelam administration (Fig. 1I) in the absence of altered gluconeogenic gene expression (data not shown). To address the effect of colesevelam treatment on hepatic glucose metabolism, independent of acute substrate and hormone influence, livers were isolated and metabolic flux was examined under normalized perfusion conditions. Livers from mice treated with colesevelam produced less glucose (Fig. 1J). Deuterium tracer incorporation showed that gluconeogenic flux was unaltered (Fig. 1K) but that glycogenolysis was robustly suppressed by colesevelam treatment (Fig. 1L). Hepatic glycogen content was elevated in mice receiving colesevelam treatment (Fig. 1M), indicating that colesevelam treatment suppresses glycogen breakdown and promotes glycogen storage. However, glycogen content was reduced normally after an overnight fast (Fig. 1M), demonstrating that hepatic glycogen mobilization is not impaired during fasting. These data suggest that the principal metabolic mechanism by which colesevelam treatment reduces hepatic glucose production in DIO mice is via suppression of glycogenolysis.

GLP-1 signaling is required for suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis.

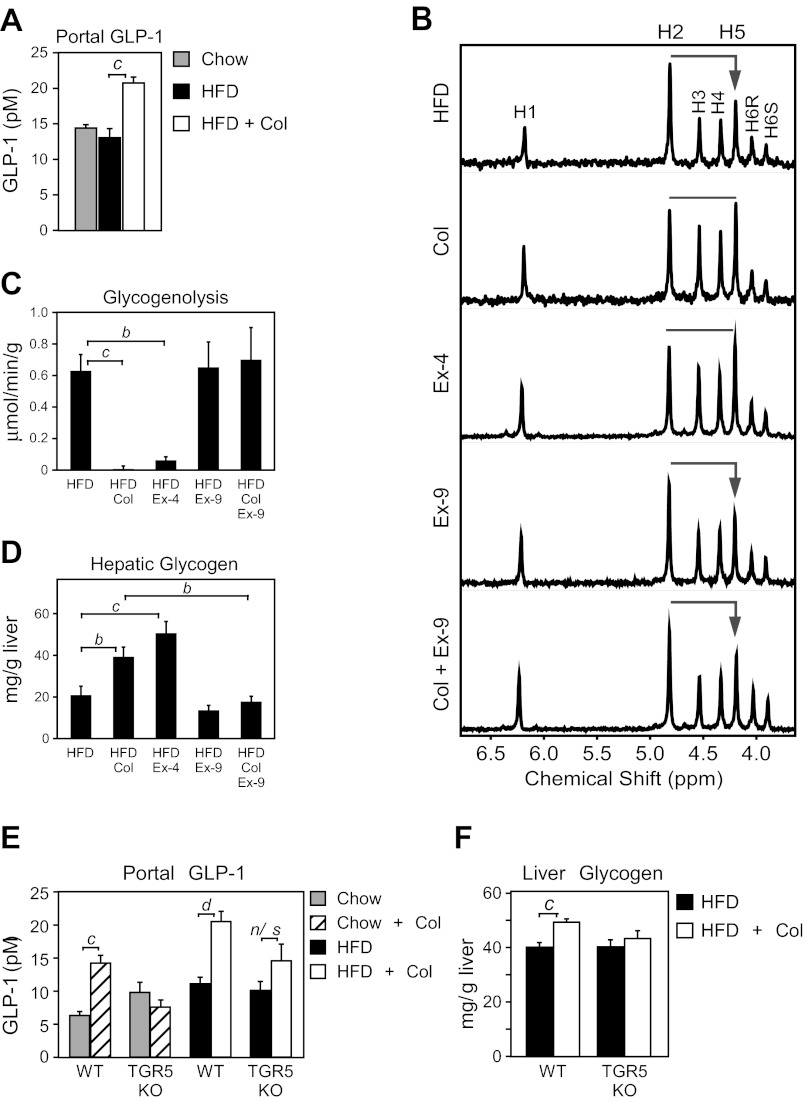

Incretins have been suggested as key mediators of the actions of bile acid sequestrants (4, 19, 36, 50), so we examined GIP and GLP-1 in DIO mice treated with colesevelam. GIP was elevated in DIO mice as previously reported (38) and reduced by colesevelam treatment (data not shown). In contrast, portal GLP-1 concentration was substantially increased by colesevelam treatment (Fig. 2A), consistent with previous studies in humans and animal models (9, 50). Because GLP-1 is known to promote glycogen storage (1, 29) and reduce hepatic glucose production (14), we examined whether elevated GLP-1 action during colesevelam treatment was responsible for the suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis. Treatment with the GLP1-R agonist, exendin-4 (Ex-4), recapitulated the elevated glucose H5/H2 deuterium enrichment (Fig. 2B) that occurred following colesevelam treatment (Fig. 2B), indicating that both treatments caused a suppression of glycogenolysis (Fig. 2, B and C). Both treatments also caused an increase in hepatic glycogen content (Fig. 2D). To determine whether the suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis requires GLP-1 action, DIO mice were treated with the GLP-1R antagonist, exendin-9 (Ex-9). Ex-9 alone did not alter hepatic glycogenolysis (Fig. 2, B and C), but coadministration of Ex-9 blocked the inhibition of hepatic glycogenolysis by colesevelam (Fig. 2, B and C) and reduced hepatic glycogen content (Fig. 2D). These data show that GLP-1 action is required for suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis during colesevelam treatment.

Fig. 2.

TGR5-mediated induction of glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 is required for Col-mediated suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis. A: GLP-1 measured in portal blood of fed WT DIO mice on a chow or HFD for 15 wk and treated with or without colesevelam HCl (HFD + Col) for 7 days (n = 6/group). B–F: WT DIO mice on HFD for 15 wk were administered either saline, the GLP-1R agonist exendin-4 (Ex-4), the GLP-1R antagonist exendin-(9–39) (Ex-9), or colesevelam (Col) with or without Ex-9 for 7 days (n = 5–6/group). B: livers from fed mice were perfused with media containing 2H2O, and the deuterium enrichment of glucose was measured by NMR, where higher H5/H2 enrichment indicates less glycogenolysis. C: hepatic glycogenolysis. D: hepatic glycogen from livers in B (n = 5–6/group). Portal GLP-1 (E) and hepatic glycogen (F) levels analyzed from WT or TGR5 knockout (KO) mice fed 15 wk with chow or a HFD and then treated with or without colesevelam HCl (HFD + Col) for 7 days (n = 5–6/group). Data are presented as means ± SE. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significance (aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; cP < 0.005; and dP < 0.001 vs. control; n/s = not significant).

TGR5 is required for colesevelam to induce GLP-1 and alter hepatic glycogen metabolism.

Because bile acid activation of TGR5 induces secretion of GLP-1 (53), we investigated whether TGR5 was required for colesevelam-mediated induction of GLP-1 and glycogen sparing. Colesevelam treatment increased the portal GLP-1 concentration in WT lean and DIO mice as expected but failed to significantly induce GLP-1 in TGR5 KO mice (Fig. 2E). Colesevelam administration also significantly increased hepatic glycogen content in WT mice, but TGR5 KO mice failed to spare hepatic glycogen (Fig. 2F), similar to the effect of ex-9 treatment.

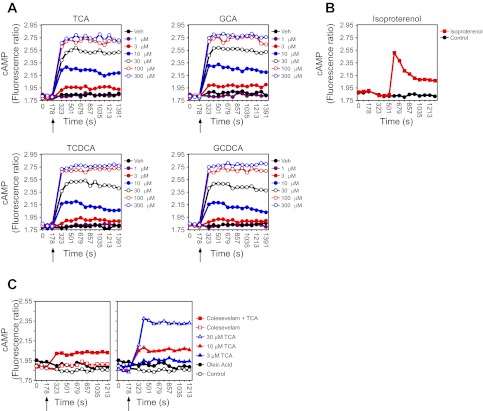

Bile acids bound to colesevelam activate a prolonged TGR5-mediated cAMP response.

The activation of TGR5 during bile acid sequestration contrasts with the deactivation of FXR, so we tested whether sequestered bile acids maintain activity against TGR5. A real-time TGR5-activity assay was developed by stably expressing human TGR5 and a BRET sensor for cAMP in HEK cells (TGR5-BRET cells) (26). As expected, treatment of TGR5-BRET cells with bile acids caused a dose-dependent increase in TGR5 activation (Fig. 3A), which was not observed in cells lacking TGR5 (data not shown). Compared with the rapid dissipation of cAMP signaling when other GPCRs are activated (e.g., isoproterenol action) (Fig. 3B), bile acid activation of TGR5 resulted in an immediate and sustained activation of cAMP signaling (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, however, treatment of TGR5-BRET cells with colesevelam that had been preloaded with TCA resulted in a marked increase in TGR5 activity, whereas colesevelam alone had no effect (Fig. 3C, left). The TGR5 activity stimulated by the bile acid-bound resin was similar to that observed with 10 μM TCA alone (Fig. 3C, right). Notably, in these experiments the bile acid-bound resin was washed several times before addition to cells, and the concentration of free bile acids in the administered sample was measured to ensure they were below detection at the time of addition. Furthermore, analysis of the media from cells treated with bile acid-bound resin revealed undetectable levels of free bile acids. These results suggest that bound bile acids or those in a rapidly exchanging complex with colesevelam are capable of activating TGR5.

Fig. 3.

Bile acid-mediated activation of TGR5 initiates a novel cAMP signaling cascade. Real-time analysis of TGR5 activation (cAMP signaling) in TGR5-bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) cells after treatment with the indicated concentrations of bile acid (BA) (A) or isoproterenol (B). C: Real-time analysis of TGR5 activation (cAMP signaling) in TGR5-BRET cells after treatment with bile acid [3, 10, and 30 μM taurocholic acid (TCA)], Colesevelam (Col) alone, oleic acid alone, or bound Col/TCA equivalent to 55 μM (see materials and methods). Arrow indicates when factors were added to cells. GCA, glycocholic acid; TCDCA, taurine chenoxycholic acid; GCDCA, glycine chenoxycholic acid.

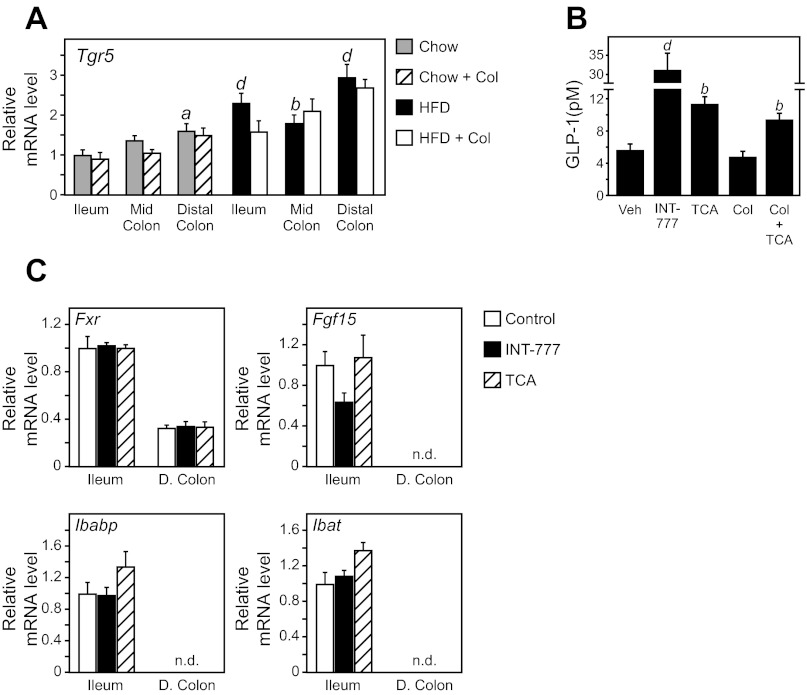

TGR5 activation in the colon is sufficient to induce GLP-1 release.

Sequestrants repartition bile acids to the colon (35), where TGR5 and GLP-1 expressing cells are abundant (11, 15, 33). We confirmed high TGR5 mRNA expression in the distal colon, which was further elevated by a HFD (Fig. 4A). We next examined whether activation of TGR5 specifically in the colon was sufficient to increase portal GLP-1 concentration. Rectal administration of either a TGR5-specific agonist (INT-777), the endogenous bile acid TCA, or a bile acid prebound to colesevelam (TCA + Col) increased portal GLP-1 levels (Fig. 4B). FXR target gene expression in the small intestine was unchanged following rectal administration of TCA (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that the injection did not penetrate the ileocecal valve and was constrained to the colon. Together, these data indicate that bile acids bound to colesevelam can activate a sustained TGR5 signaling mechanism and that activation of this pathway in colon elicits a robust induction of GLP-1 concentration.

Fig. 4.

Col-mediated activation of TGR5 in the colon induces GLP-1. A: WT C57Bl/6 mice fed a chow diet or induced to obesity by a 60% HFD for 15 wk were supplemented with and without Colesevelam (Col) for 7 days. Tgr5 mRNA expression in ileum, mid-colon (M. Colon), and distal colon (D. Colon) was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (n = 6/group). B: portal GLP-1 levels in WT mice 40 min after rectal administration of vehicle, INT-777, TCA, Col alone, or Col preincubated with TCA (Col + TCA) (n = 4–5/group). C: ileum and distal colon (D. Colon) gene expression from mice in B. Data are presented as means ± SE. The presence of different lowercase letters indicates statistical significance relative to ileal gene expression from chow fed mice (aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; and dP < 0.001 vs. control; n.d. = not detected).

TGR5/GLP-1 activation is not required for colesevelam to improve cholesterol metabolism and is not solely responsible for reducing hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia.

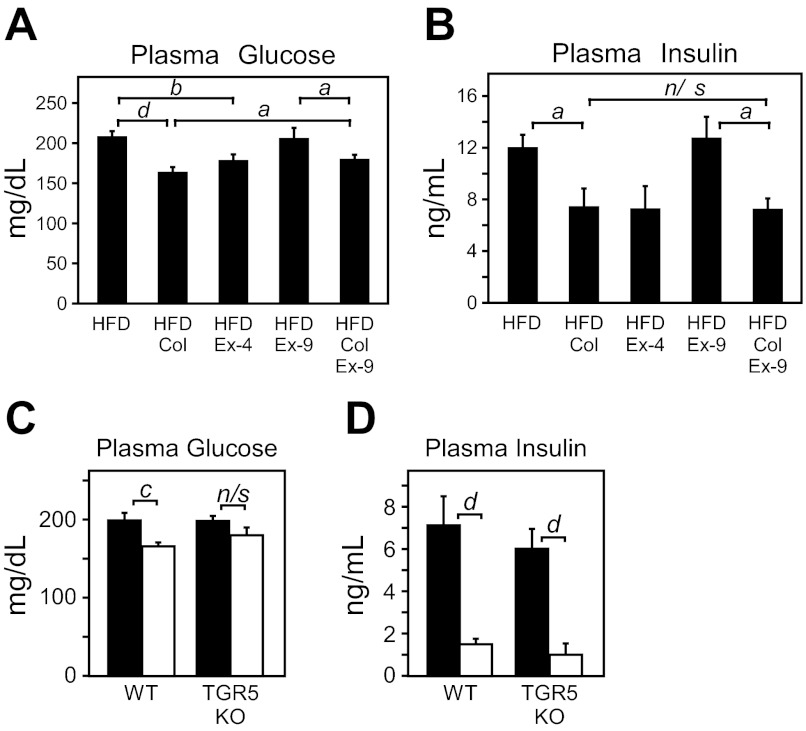

TGR5 activation and GLP-1 induction only partially explain the metabolic benefits of colesevelam. Ex-9 mildly blunted the efficacy of colesevelam against plasma glucose concentration, consistent with reduced hepatic glucose production. However, ex-9 did not completely prevent the reduction of plasma glucose (Fig. 5A) and had very little effect on the ability of colesevelam to reduce hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 5B). TGR5 KO mice did not significantly induce GLP-1 during colesevelam treatment and also failed to significantly lower hyperglycemia although glucose trended lower (P = 0.1) (Fig. 5C). Despite no significant effect on GLP-1 or glycemia, colesevelam robustly reduced hyperinsulinemia in TGR5 KO mice (Fig. 5D). Thus TGR5/GLP-1 activation is required for colesevelam to suppress hepatic glycogenolysis and is partially responsible for improved glycemia but other targets contribute to its effects on hyperinsulinemia.

Fig. 5.

TGR5-mediated induction of GLP-1 contributes to Col-mediated suppression of hyperglycemia but not hyperinsulinemia in DIO mice. Plasma glucose (A) and insulin levels (B) from WT DIO mice on HFD for 15 wk were administered either saline, the GLP-1R agonist exendin-4 (Ex-4), the GLP-1R antagonist exendin-(9–39) (Ex-9), or colesevelam (Col) with or without Ex-9 for 7 days (n = 5–6/group). Plasma glucose (C) and (D) insulin levels from WT or TGR5 KO mice fed 15 wk a HFD and then treated with or without colesevelam HCl (HFD + Col) for 7 days (n = 5–6/group). Data are presented as means ± SE. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significance (aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; cP < 0.005; and dP < 0.001 vs. control; n/s = not significant).

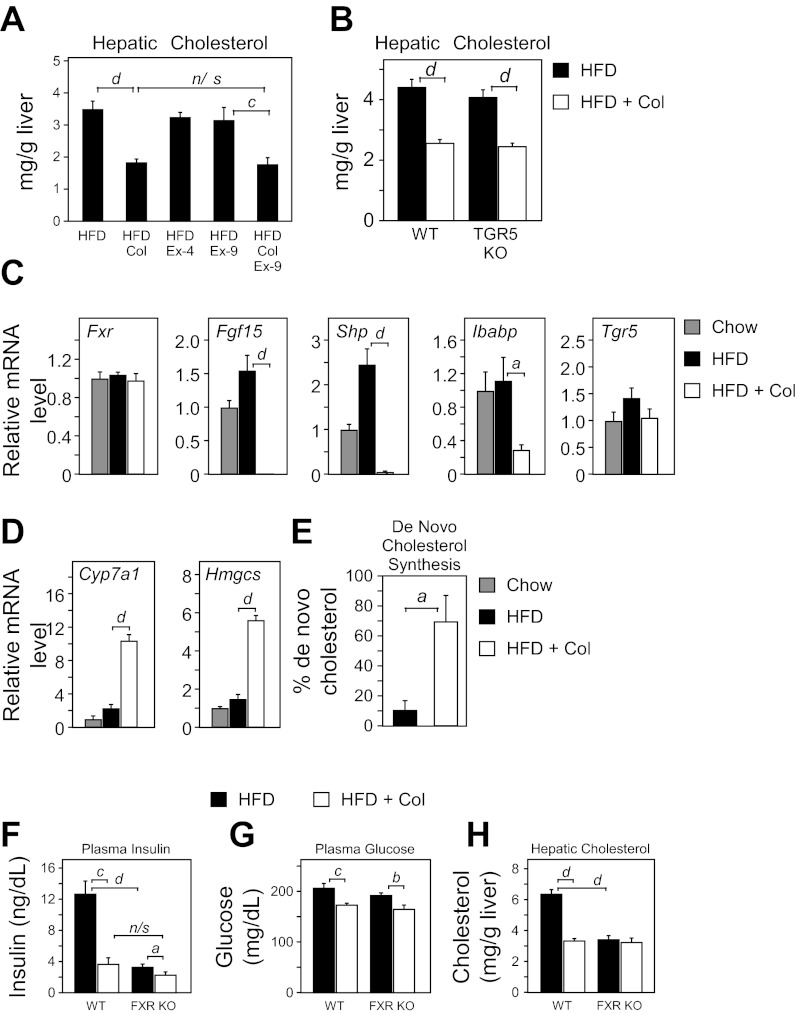

The ability of colesevelam to reduce hepatic cholesterol was independent of GLP-1 (Fig. 6A) and TGR5 (Fig. 6B). In agreement with previous studies (20), there was a near complete loss of FXR target genes (Fgf15, Shp, and Ibabp) in the ileum (Fig. 6C). Consistent with the loss of ileal FGF15, hepatic expression of cholesterol biosynthetic genes (Cyp7a1 and Hmgcs) was markedly induced (Fig. 6D), and cholesterol synthesis was increased by sevenfold (Fig. 6E). Blocking GLP-1 action with ex-9 had no effect on the expression of ileal FXR targets or hepatic genes of cholesterol synthesis (data not shown). Thus the effects of colesevelam on FXR and cholesterol metabolism are independent of TGR5 activation and GLP-1 release.

Fig. 6.

Farnesoid X receptor (FXR), but not TGR5/GLP-1, is required for Col-mediated remediation of hepatic cholesterol levels. A: hepatic cholesterol levels from WT DIO mice on HFD for 15 wk were administered either saline, the GLP-1R agonist exendin-4 (Ex-4), the GLP-1R antagonist exendin-(9–39) (Ex-9), or colesevelam (Col) with or without Ex-9 for 7 days (n = 5–6/group). B: hepatic cholesterol levels from WT or TGR5 KO mice fed 15 wk a HFD and then treated with or without colesevelam HCl (HFD + Col) for 7 days (n = 5–6/group). Ileum (C) or hepatic gene (D) expression from WT chow, HFD, and HFD + Col fed mice. E: measurement of de novo cholesterol synthesis in HFD and HFD + Col mice. Plasma insulin (F), plasma glucose (G), and hepatic cholesterol (H) levels from WT or FXR KO mice fed HFD for 15 wk and then treated with or without colesevelam HCl (HFD + Col) for 7 days (n = 5–6/group). Data are presented as means ± SE. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significance (aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; cP < 0.005; and dP < 0.001 vs. control; n/s = not significant).

Because regulation of FXR activity influences glycemia and insulin sensitivity (28, 44), we next examined whether FXR contributes to the GLP-1-independent effects of colesevelam on hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia. FXR KO mice were induced to obesity by a HFD and treated with or without colesevelam. FXR KO mice on a HFD recapitulated the lower insulin concentration observed during colesevelam treatment (Fig. 6F). However, colesevelam treatment in FXR KO mice still decreased insulin slightly (Fig. 6F), and glucose concentration was reduced in a manner similar to WT mice (Fig. 6G). Notably, DIO FXR KO mice exhibited markedly lower hepatic cholesterol levels comparable to WT DIO mice administered colesevelam (Fig. 6H). Moreover, administration of colesevelam to DIO FXR KO mice did not further reduce hepatic cholesterol levels (Fig. 6H). Thus the effect of colesevelam on GLP-1R activation and FXR deactivation both have important therapeutic effects, but neither is independently sufficient for colesevelam to lower glycemia or hyperinsulinemia.

DISCUSSION

Bile acid sequestrants disrupt the normal enterohepatic circulation of bile acids and alter the activity of bile acid receptors in the intestine. Sequestrants improve hypercholesterolemia by inhibiting the bile acid nuclear receptor FXR, resulting in the derepression of bile acid synthesis and the clearance of cholesterol into the bile acid pool. In contrast, the effect of sequestrants on glycemia (17) is not well understood. A role for GLP-1 in the glycemic action of colesevelam was anticipated after several studies noted that sequestrant treatment increased plasma GLP-1 concentration in rodents (9, 50) and humans (4). GLP-1 is a gut incretin that is critical for glycemic regulation, and several classes of drugs that mimic or stabilize GLP-1 are effective against hyperglycemia (34). Bile acids induce GLP-1 by activating TGR5 on the surface of intestinal L cells (42). The physiological relevance of bile acid mediated GLP-1 release in glycemic regulation is indicated by reduced plasma glucose after bile acid administration (53) and is confirmed by the blunted glycemic effect of bile acids in GLP-1R KO mice (47). In contrast to the expected deactivation of FXR by bile acid sequestration, sequestrants appear to augment TGR5 activation and GLP-1 release (19).

DIO mice treated with colesevelam had elevated GLP-1, improved glucose tolerance, and reduced hyperinsulinemia. Hepatic glucose production was reduced due to suppressed glycogenolysis, a finding that is consistent with Beysen and colleagues who reported that colesevelam lowered glycogenolysis but not gluconeogenesis in humans (4). Because GLP-1R activation spares hepatic glycogen (29), we tested whether colesevelam suppresses glycogenolysis by TGR5-mediated GLP-1 action. A GLP-1R agonist (ex-4) recapitulated the effect of colesevelam on hepatic glycogenolysis, and a GLP-1R antagonist (ex-9) blocked the effect and resulted in increased hepatic glycogen. The failure of TGR5 KO mice to significantly induce GLP-1, lower glucose, or spare hepatic glycogen indicated that TGR5 activation during colesevelam treatment is required for these effects.

GLP-1 regulates hepatic glucose metabolism (5a, 24), but the mechanism is unclear because the GLP-1R is not expressed in hepatocytes (10). The putative incretin effect of GLP-1 is to induce pancreatic insulin and suppress glucagon secretion, a hormonal maneuver that should favor hepatic glycogen synthesis over glycogenolysis. However, portal glucagon was surprisingly increased, and hepatic glucagon receptor expression was unchanged. Markedly decreased insulin and plasma glucose during colesevelam treatment indicates improved insulin sensitivity, which makes it difficult to interpret the changes in the concentration of circulating glucoregulatory hormones, inasmuch as they will adapt to concentrations appropriate for lower glycemia. It remains possible that pancreatic function is improved during an oral nutrient challenge or that favorable changes in insulin and/or glucagon action (rather than concentration) contribute to the effects of colesevelam on hepatic glucose metabolism. GLP-1R activation may also modify glycogen metabolism and glucose production independent of its incretin effects (1, 29) by direct activation of the GLP-1R in portal vein nerves (39, 40) or central mediation of liver metabolism by hypothalamic GLP-1R activation (8, 29, 49).

Several aspects of sequestrant efficacy could not be attributed to TGR5/GLP-1. Not surprisingly, the favorable effect of colesevelam on cholesterol regulatory genes and metabolism was associated with deactivation of FXR, independent of TGR5 or GLP-1R loss of function. On the other hand, the finding that GLP-1R inhibition completely blocked the effect of colesevelam on hepatic glycogenolysis, but only partially reduced its ability to lower glycemia, was surprising. In contrast, TGR5 KO mice did not significantly reduce basal glucose when treated with colesevelam, indicating that TGR5 activation is critical for the glycemic effect (Fig. 5C and Ref. 19). It is possible that the Ex-9 dose used here only partially inhibited GLP-1R activation and thus underestimates the role of GLP-1R activation during colesevelam treatment. Alternatively, TGR5 activation can also improve glucose homeostasis independent of GLP-1. Systemic bile acid activation of TGR5 has been reported to improve glucose homeostasis by increasing energy expenditure during 3 mo of sequestrant treatment (56), but we did not find changes in energy expenditure after 7 days of colesevelam treatment (not shown). We also note that a glucose-lowering effect in TGR5 KO mice narrowly missed statistical significance, and both Ex-9 and TGR5 KO mice robustly improved hyperinsulinemia during treatment. Thus the GLP-1/TGR5 axis is critical for improved hepatic glucose metabolism but is unlikely the sole factor by which colesevelam improves glycemic regulation.

FXR and its intestinal target FGF15 regulate glucose homeostasis and glucose clearance (28, 44). Genetic loss of FXR activity improves glucose clearance in db/db mice (46). Sequestrants also increase glucose clearance in humans (4) and in db/db mice, where this increase has been attributed to reduced FXR activity (37). In contrast, endogenous glucose production was reduced in DIO mice, perhaps due to the lesser severity of this model compared with the db/db mouse. Nonetheless, our findings do not obviate a role for FXR mediated glucose clearance especially during nutrient load. FXR loss of function recapitulated the lower insulin levels induced by colesevelam treatment, consistent with decreased FXR activation by sequestrants. However, FXR KO mice treated with colesevelam still achieved a slight reduction in insulin and maintained a robust glycemic response to treatment. Thus it is possible that a combination of FXR-dependent insulin sensitization and TGR5/GLP-1-dependent glucose disposition (i.e., glycogen storage) are important for the glycemic efficacy of colesevelam, but neither appears independently sufficient to mediate these effects.

The activation of one bile acid receptor (cell surface TGR5) and suppression of another (nuclear FXR) are unique pharmacological properties of sequestrant treatment. TGR5 is highly expressed in the distal colon (Fig. 4A) (11, 15, 33), whereas FXR is mainly expressed in the small intestine (Fig. 4C). During sequestrant treatment, bile acids in the small intestine are sequestered and unable to enter the cell to activate FXR (20), but once transported to the colon (13) differences in pH (16) and motility increase free bile acid levels (35). We found that ectopic bile acids in the colon result in elevated portal GLP-1 concentration and that the effect was maintained when the bile acid was complexed to colesevelam (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, bile acids triggered sustained activation of TGR5 signaling in cell-based assays, and this activation was maintained (although to a lesser level) despite the presence of a saturating concentration of colesevelam (Fig. 3C). Thus sequestrants inhibit FXR activation by excluding the cellular transport of bile acids in the small intestine, but cell surface TGR5 can be activated in the colon by dissociated and/or bound bile acids. Lipid receptors (21, 31) also stimulate GLP-1 secretion (57), and we observed a slight (3%) decrease in lipid absorption with colesevelam treatment (data not shown). In addition, sequestrants also induce other gut hormones (36), including GIP (4). However, GIP is artificially elevated by high-fat feeding in mice (38) and was normalized independent of TGR5 by colesevelam. It is possible that a combination of FXR- and TGR5-independent factors contribute to the pharmacology of sequestrants, but their roles remain to be elucidated.

In summary, colesevelam reduced hepatic glucose production by suppressing glycogenolysis in DIO mice. The suppression of hepatic glycogenolysis required TGR5 and GLP-1R activation. TGR5 could be activated by the bile acid-colesevelam complex in vitro, and its activation in the colon was sufficient to induce GLP-1. However, TGR5/GLP-1R activation was unrelated to improved hypercholesterolemia or hyperinsulinemia and may only partially explain glycemic efficacy of colesevelam. Suppression of FXR mediated the cholesterol effect and may reduce hyperinsulinemia but was not sufficient for the glycemic effect of colesevelam. This unique polypharmacology of colesevelam impinges on multiple receptors, hormones, and metabolic pathways, which contribute to improve hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycemia.

GRANTS

Support for this work was provided in part by the NIH RO1DK078184 (S. Burgess), U19 DK62434 (D. Mangelsdorf), UL1-DE019584 (S. Burgess, D. Mangelsdorf, S. Kliewer) Cores within RR02584 and, by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D. Mangelsdorf., M. Potthoff), a research grant from Daiichi Sankyo, the Robert A. Welch Foundation (I-1275 to D. Mangelsdorf and I-1558 to S. Kliewer), and by the American Diabetes Association (7-09-BS-24 to S. Burgess).

DISCLOSURES

We disclose that this work was partially funded by an Investigator Initiated Study Protocol from Daiichi Sankyo who makes and markets colesevelam. Drs. Burgess, Kliewer, and Mangelsdorf have also served as consultants for DS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.J.P., R.T., D.J.M., S.A.K., and S.C.B. conception and design of research; M.J.P., A.P., T.H., J.A.D., R.T., D.J.M., and S.A.K. performed experiments; M.J.P., A.P., J.A.D., R.T., D.J.M., S.A.K., and S.C.B. analyzed data; M.J.P., R.T., D.J.M., S.A.K., and S.C.B. interpreted results of experiments; M.J.P., R.T., D.J.M., and S.A.K. prepared figures; M.J.P., R.T., D.J.M., S.A.K., and S.C.B. drafted manuscript; M.J.P., R.T., D.J.M., S.A.K., and S.C.B. edited and revised manuscript; M.J.P., S.A.K., and S.C.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Current address for M. Potthoff: Department of Pharmacology, Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242.

We thank Tingting Li, Richard Davis, and Yuan Zhang for technical assistance. Glucagon and lipid absorption assays were performed by the Vanderbilt (DK-059637) and U. Cincinnati (DK-059630) MMPCs, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, James FD, Julien BM, Wasserman DH, Drucker DJ. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor regulates endogenous glucose production and muscle glucose uptake independent of its incretin action. Endocrinology 150: 1155–1164, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu R, Chandramouli V, Dicke B, Landau B, Rizza R. Obesity and type 2 diabetes impair insulin-induced suppression of glycogenolysis as well as gluconeogenesis. Diabetes 54: 1942–1948, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Best JD, Judzewitsch RG, Pfeifer MA, Beard JC, Halter JB, Porte D., Jr The effect of chronic sulfonylurea therapy on hepatic glucose production in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes 31: 333–338, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beysen C, Murphy EJ, Deines K, Chan M, Tsang E, Glass A, Turner SM, Protasio J, Riiff T, Hellerstein MK. Effect of bile acid sequestrants on glucose metabolism, hepatic de novo lipogenesis, and cholesterol and bile acid kinetics in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled study. Diabetologia 55: 432–442, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braunlin W, Zhorov E, Smisek D, Guo A, Appruzese W, Xu Q, Hook P, Holmes-Farley R, Mandeville H. In vitro comparison of bile acid binding to colesevelam hcl and other bile acid sequestrants. Polymer Preprints 41: 708–709, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Burcelin R, Da Costa A, Drucker D, Thorens B. Glucose competence of the hepatoportal vein sensor requires the presence of an activated glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. Diabetes 50: 1720–1728, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess SC, Jeffrey FMH, Storey C, Milde A, Hausler N, Merritt ME, Mulder H, Holm C, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Effect of murine strain on metabolic pathways of glucose production after brief or prolonged fasting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289: E53–E61, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgess SC, Nuss M, Chandramouli V, Hardin DS, Rice M, Landau BR, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. Analysis of gluconeogenic pathways in vivo by distribution of 2H in plasma glucose: comparison of nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem 318: 321–324, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burmeister MA, Ferre T, Ayala JE, King EM, Holt RM, Ayala JE. Acute activation of central GLP-1 receptors enhances hepatic insulin action and insulin secretion in high-fat-fed, insulin resistant mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E334–E343, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, McNulty J, Anderson D, Liu Y, Nystrom C, Bullard S, Collins J, Handlon AL, Klein R, Grimes A, Murray D, Brown R, Krull D, Benson B, Kleymenova E, Remlinger K, Young A, Yao X. Cholestyramine reverses hyperglycemia and enhances glucose-stimulated glucagon-like peptide 1 release in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334: 164–170, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Alessio D, Vahl T, Prigeon R. Effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 on the hepatic glucose metabolism. Horm Metab Res 36: 837–841, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damholt AB, Kofod H, Buchan AM. Immunocytochemical evidence for a paracrine interaction between GIP and GLP-1-producing cells in canine small intestine. Cell Tissue Res 298: 287–293, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding J, Gao Y, Zhao J, Yan H, Guo SY, Zhang QX, Li LS, Gao X. Pax6 haploinsufficiency causes abnormal metabolic homeostasis by down-regulating glucagon-like peptide 1 in mice. Endocrinology 150: 2136–2144, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donovan JM, Von Bergmann K, Setchell KD, Isaacsohn J, Pappu AS, Illingworth DR, Olson T, Burke SK. Effects of colesevelam HC1 on sterol and bile acid excretion in patients with type IIa hypercholesterolemia. Dig Dis Sci 50: 1232–1238, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 368: 1696–1705, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eissele R, Goke R, Willemer S, Harthus HP, Vermeer H, Arnold R, Goke B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 cells in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas of rat, pig and man. Eur J Clin Invest 22: 283–291, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans DF, Pye G, Bramley R, Clark AG, Dyson TJ, Hardcastle JD. Measurement of gastrointestinal pH profiles in normal ambulant human subjects. Gut 29: 1035–1041, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg A, Grundy SM. Cholestyramine therapy for dyslipidemia in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A short-term, double-blind, crossover trial. Ann Intern Med 121: 416–422, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanus M, Zhorov E. Bile acid salt binding with colesevelam HCl is not affected by suspension in common beverages. J Pharm Sci 95: 2751–2759, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harach T, Pols TW, Nomura M, Maida A, Watanabe M, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. TGR5 potentiates GLP-1 secretion in response to anionic exchange resins. Sci Rep 2: 430, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrema H, Meissner M, van Dijk TH, Brufau G, Boverhof R, Oosterveer MH, Reijngoud DJ, Muller M, Stellaard F, Groen AK, Kuipers F. Bile salt sequestration induces hepatic de novo lipogenesis through farnesoid X receptor- and liver X receptoralpha-controlled metabolic pathways in mice. Hepatology 51: 906–815, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Yamada M, Sugimoto Y, Miyazaki S, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med 11: 90–94, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, Peng L, Cummins CL, McDonald JG, Luo G, Jones SA, Goodwin B, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab 2: 217–225, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insull W., Jr Clinical utility of bile acid sequestrants in the treatment of dyslipidemia: a scientific review. South Med J 99: 257–273, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ionut V, Hucking K, Liberty IF, Bergman RN. Synergistic effect of portal glucose and glucagon-like peptide-1 to lower systemic glucose and stimulate counter-regulatory hormones. Diabetologia 48: 967–975, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang LI, Collins J, Davis R, Fraser ID, Sternweis PC. Regulation of cAMP responses by the G12/13 pathway converges on adenylyl cyclase VII. J Biol Chem 283: 23429–23439, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang LI, Collins J, Davis R, Lin KM, DeCamp D, Roach T, Hsueh R, Rebres RA, Ross EM, Taussig R, Fraser I, Sternweis PC. Use of a cAMP BRET sensor to characterize a novel regulation of cAMP by the sphingosine 1-phosphate/G13 pathway. J Biol Chem 282: 10576–10584, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalaany NY, Gauthier KC, Zavacki AM, Mammen PP, Kitazume T, Peterson JA, Horton JD, Garry DJ, Bianco AC, Mangelsdorf DJ. LXRs regulate the balance between fat storage and oxidation. Cell Metab 1: 231–244, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kir S, Beddow SA, Samuel VT, Miller P, Previs SF, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Shulman GI, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science 331: 1621–1624, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knauf C, Cani PD, Perrin C, Iglesias MA, Maury JF, Bernard E, Benhamed F, Gremeaux T, Drucker DJ, Kahn CR, Girard J, Tanti JF, Delzenne NM, Postic C, Burcelin R. Brain glucagon-like peptide-1 increases insulin secretion and muscle insulin resistance to favor hepatic glycogen storage. J Clin Invest 115: 3554–3563, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamont BJ, Drucker DJ. Differential antidiabetic efficacy of incretin agonists versus DPP-4 inhibition in high fat fed mice. Diabetes 57: 190–198, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lan H, Vassileva G, Corona A, Liu L, Baker H, Golovko A, Abbondanzo SJ, Hu W, Yang S, Ning Y, Del Vecchio RA, Poulet F, Laverty M, Gustafson EL, Hedrick JA, Kowalski TJ. GPR119 is required for physiological regulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion but not for metabolic homeostasis. J Endocrinol 201: 219–230, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landau BR, Wahren J, Chandramouli V, Schumann WC, Ekberg K, Kalhan SC. Use of 2H2O for estimating rates of gluconeogenesis. Application to the fasted state. J Clin Invest 95: 172–178, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsson LI, Holst J, Hakanson R, Sundler F. Distribution and properties of glucagon immunoreactivity in the digestive tract of various mammals: an immunohistochemical and immunochemical study. Histochemistry 44: 281–290, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lovshin JA, Drucker DJ. Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5: 262–269, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luner PE, Amidon GL. Description and simulation of a multiple mixing tank model to predict the effect of bile sequestrants on bile salt excretion. J Pharm Sci 82: 311–318, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marina AL, Utzschneider KM, Wright LA, Montgomery BK, Marcovina SM, Kahn SE. Colesevelam improves oral but not intravenous glucose tolerance by a mechanism independent of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function. Diabetes Care 35: 1119–1125, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meissner M, Herrema H, van Dijk TH, Gerding A, Havinga R, Boer T, Müller M, Reijngoud DJ, Groen AK, Kuipers F. Bile acid sequestration reduces plasma glucose levels in db/db mice by increasing its metabolic clearance rate. PLos One 6: e24564, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Ban N, Ihara Y, Tsukiyama K, Zhou H, Fujimoto S, Oku A, Tsuda K, Toyokuni S, Hiai H, Mizunoya W, Fushiki T, Holst JJ, Makino M, Tashita A, Kobara Y, Tsubamoto Y, Jinnouchi T, Jomori T, Seino Y. Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents obesity. Nat Med 8: 738–742, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakabayashi H, Nishizawa M, Nakagawa A, Takeda R, Niijima A. Vagal hepatopancreatic reflex effect evoked by intraportal appearance of tGLP-1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 271: E808–E813, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishizawa M, Nakabayashi H, Uchida K, Nakagawa A, Niijima A. The hepatic vagal nerve is receptive to incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1, but not to glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, in the portal vein. J Auton Nerv Syst 61: 149–154, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Out C, Groen AK, Brufau G. Bile acid sequestrants: more than simple resins. Curr Opin Lipidol 23: 43–55, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parker HE, Wallis K, le Roux CW, Wong KY, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Molecular mechanisms underlying bile acid-stimulated glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Br J Pharmacol 165: 414–423, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pols TW, Noriega LG, Nomura M, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. The bile acid membrane receptor TGR5: a valuable metabolic target. Dig Dis 29: 37–44, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potthoff MJ, Boney-Montoya J, Choi M, He T, Sunny NE, Satapati S, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Gerard RD, Finck BN, Burgess SC, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. FGF15/19 Regulates Hepatic Glucose Metabolism by Inhibiting the CREB-PGC-1alpha Pathway. Cell Metab 13: 729–738, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potthoff MJ, Inagaki T, Satapati S, Ding X, He T, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Finck BN, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA, Burgess SC. FGF21 induces PGC-1alpha and regulates carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism during the adaptive starvation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10853–10858, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prawitt J, Abdelkarim M, Stroeve JHM, Popescu I, Duez H, Velagapudi VR, Dumont J, Bouchaert E, van Dijk TH, Lucas A, Dorchies E, Daoudi M, Lestavel S, Gonzalez FJ, Oresic M, Cariou B, Kuipers F, Caron S, Staels B. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency improves glucose homeostasis in mouse models of obesity. Diabetes 60: 1861–1871, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rafferty EP, Wylie AR, Hand KH, Elliott CE, Grieve DJ, Green BD. Investigating the effects of physiological bile acids on GLP-1 secretion and glucose tolerance in normal and GLP-1R(-/-) mice. Biol Chem 392: 539–546, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russell DW. The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 137–174, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandoval DA, Bagnol D, Woods SC, D'Alessio DA, Seeley RJ. Arcuate glucagon-like peptide 1 receptors regulate glucose homeostasis but not food intake. Diabetes 57: 2046–2054, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shang Q, Saumoy M, Holst JJ, Salen G, Xu G. Colesevelam improves insulin resistance in a diet-induced obesity (F-DIO) rat model by increasing the release of GLP-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G419–G424, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sinal CJ, Tohkin M, Miyata M, Ward JM, Lambert G, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 102: 731–744, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sunny NE, Bequette BJ. Gluconeogenesis differs in developing chick embryos derived from small compared with typical size broiler breeder eggs. J Anim Sci 88: 912–921, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas C, Gioiello A, Noriega L, Strehle A, Oury J, Rizzo G, Macchiarulo A, Yamamoto H, Mataki C, Pruzanski M, Pellicciari R, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. TGR5-mediated bile acid sensing controls glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab 10: 167–177, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vassileva G, Golovko A, Markowitz L, Abbondanzo SJ, Zeng M, Yang S, Hoos L, Tetzloff G, Levitan D, Murgolo NJ, Keane K, Davis HR, Jr, Hedrick J, Gustafson EL. Targeted deletion of Gpbar1 protects mice from cholesterol gallstone formation. Biochem J 398: 423–430, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watanabe M, Morimoto K, Houten SM, Kaneko-Iwasaki N, Sugizaki T, Horai Y, Mataki C, Sato H, Murahashi K, Arita E, Schoonjans K, Suzuki T, Itoh H, Auwerx J. Bile acid binding resin improves metabolic control through the induction of energy expenditure. PLos One 7: e38286, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoder SM, Yang Q, Kindel TL, Tso P. Stimulation of incretin secretion by dietary lipid: is it dose dependent? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G299–G305, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]