Abstract

This Protocol describes a single vesicle-vesicle microscopy system to study Ca2+-triggered vesicle fusion. Donor vesicles contain reconstituted synaptobrevin and synaptotagmin-1. Acceptor vesicles contain reconstituted syntaxin and SNAP-25, and are tethered to a PEG-coated glass surface. Donor vesicles are mixed with the tethered acceptor vesicles and incubated for several minutes at zero Ca2+-concentration, resulting in a collection of single interacting vesicle pairs. The donor vesicles also contain two spectrally distinct fluorophores that allow simultaneous monitoring of temporal changes of the content and membrane. Upon Ca2+-injection into the sample chamber, our system therefore differentiates between hemifusion and complete fusion of interacting vesicle pairs and determines the temporal sequence of these events on a sub-hundred millisecond timescale. Other factors, such as complexin, can be easily added. Our system is unique by monitoring both content and lipid mixing, and by starting from a metastable state of interacting vesicle pairs prior to Ca2+-injection.

Keywords: Membrane biology; vesicle fusion; membrane fusion; sulforhodamine B; 1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3',3'-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate; DiIC18(5); DiD; cascade blue; SNARE; Ca2+; fluorescence microscopy; TIR; total internal reflection

Introduction

Ca2+-triggered exocytosis occurs in a number of biological processes such as neurotransmission1,2, peptide release from neuroendocrine cells3,4, and granular secretion from mast cells5. In the case of neurotransmission, fusion events between synaptic vesicles and the active zone in the presynaptic membrane are tightly controlled by protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions involving SNAREs, synaptotagmin, complexin, Munc18, Munc13, and other proteins6,7,2,8-11. The role of these and other proteins have been subject to intense investigations and controversies. In vitro assays play an important role for uncovering the molecular mechanism of action of synaptic vesicle fusion since they allow manipulations and observations not possible in vivo.

In vitro ensemble assays with reconstituted proteoliposomes have been widely used to study SNARE-mediated membrane fusion12. Clearly, these early assays were important to establish that SNAREs have fusogenic activity. However, nearly all of these studies monitored lipid mixing only, defined as the exchange of lipids between membranes, rather than content mixing. Despite the ease of such ensemble lipid mixing assays, they are subject to numerous pitfalls. Most importantly, monitoring lipid mixing alone can be misleading since lipid mixing can occur without or with significantly delayed content mixing, that is the exchange or release of aqueous content: SNAREs alone do not produce much content mixing, although SNAREs readily induce lipid mixing13,14, influenza virus-induced fusion content mixing occurs seconds after initial lipid mixing15, and content mixing occurs with minute delay after lipid mixing in vacuolar fusion16. When membrane fusion is induced by DNA-zippering even inner leaflet mixing can occur without complete fusion17, although this intriguing observation will require verification with synaptic-protein induced fusion. We recently found an even more striking difference between content mixing and lipid mixing for Ca2+-triggered fusion with synaptic proteins18.

Content mixing measurements have been notoriously difficult to achieve for ensemble-based assays because of a number of technical hurdles, including potential leakiness of proteoliposomes, aggregation, and vesicle rupture that may plague ensemble experiments. Such phenomena may produce a large fluorescence intensity change that may not be directly related to genuine fusion. Another issue with commonly used lipid-mixing ensemble experiments is that they cannot distinguish between docking and hemifusion/fusion since the observed lipid-mixing signal depends on both processes19. On a different note, some of the first ensemble lipid mixing studies used an unreasonably high protein to lipid ratio (e.g., 1:10 for synaptobrevin reconstituted vesicles12); this is a concern since high protein concentrations are known to cause vesicle instabilities. Finally, ensemble measurements may obscure heterogeneous fusion pathways since they only observe averages rather than individual fusion events. This is indeed a problem for ensemble experiments since single-vesicle lipid-mixing experiments revealed multiple intermediates in SNARE-mediated fusion20,21, and our recent single vesicle-vesicle content/lipid mixing experiments showed the existence of multiple fusion pathways for Ca2+-triggered fusion with synaptic proteins18.

Single vesicle microscopy approaches can overcome these problems with ensemble assays. However, many in vitro studies of SNARE-mediated fusion with proteoliposomes at the single vesicle level, again, used only lipid-mixing indicators. For example, a tethered vesicle assay monitored fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between fluorescent lipids in donor and acceptor-dye containing vesicles, respectively20,22. A different single vesicle assay employed fluorescent lipids in synaptobrevin vesicles in order to observe the docking and fusion events on brushed supported lipid bilayers with reconstituted syntaxin/SNAP-2521,23. However, even at a single vesicle level, lipid mixing is not necessarily indicative of content mixing, especially since it is often not possible to resolve two distinct lipid mixing events that would correspond to outer and inner leaflet mixing of a single interacting vesicle pair, respectively14; furthermore there is the abovementioned possibility of inner leaflet mixing without content mixing. It is thus essential to use robust and reliable content mixing assays to study biological membrane fusion.

Using the soluble content marker calcein, our laboratory observed only very rare fusion between neuronal SNARE-only containing vesicles and supported bilayers13; another group reported mostly vesicle bursting with this content marker, indicating that this particular soluble dye may have destabilized their particular vesicles24. More recently, relatively large content indicators (much larger than typical neurotransmitter molecules, such as glutamate) consisting of DNA hairpins were employed for a tethered single-vesicle assay25,26.

Our single vesicle assay14 uses the small water-soluble dye sulforhodamine B in order to monitor content mixing. It is important to note that this fluorophore did not destabilize our proteoliposomes which mimic physiological lipid compositions and protein densities (protein to lipid ratios). We also monitored the state of the membrane with the lipid dye DiD, and the arrival of Ca2+ in the evanescent field with cascade blue dye. Our assay simultaneously monitors the temporal sequence of content release and lipid mixing of single vesicle pairs on a sub-hundred millisecond timescale (Figs. 1-4).

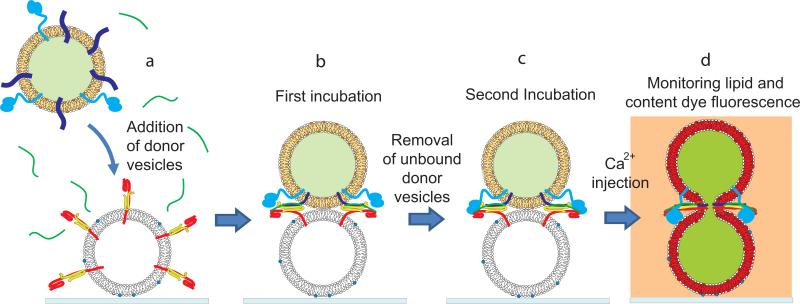

Figure 1.

Schematic of the single vesicle-vesicle microscopy system. (a) Donor vesicles labeled with self-quenched sulforhodamine B (content dye) and DiD (lipid dye) along with complexin are added to the sample chamber containing acceptor vesicles immobilized on a cover glass surface via biotin-neutravidin interactions. (b) During the first, short, incubation period (typically 10 to 30 seconds), donor vesicles are allowed to interact with acceptor vesicles. Excess donor vesicles are then rinsed away by buffer exchange. (c) A second, longer, incubation period (typically 30 mins) follows. (d) Ca2+ buffer, along with cascade blue dye is injected. Content and lipid mixing events are monitored by observing changes in fluorescence intensity of the content and lipid dyes, respectively. The observation period typically starts 5 seconds prior to the Ca2+ injection and can typically last 30 to 50 seconds (limited by photobleaching).

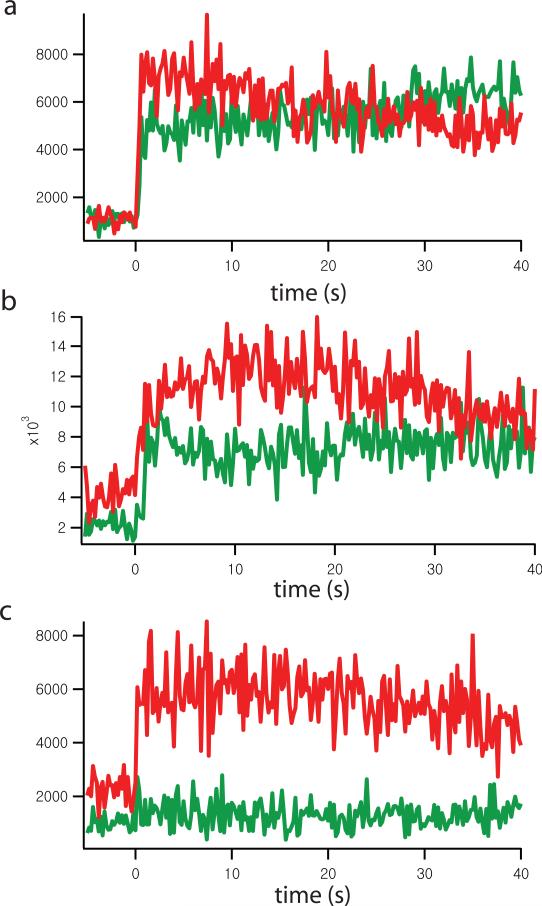

Figure 4.

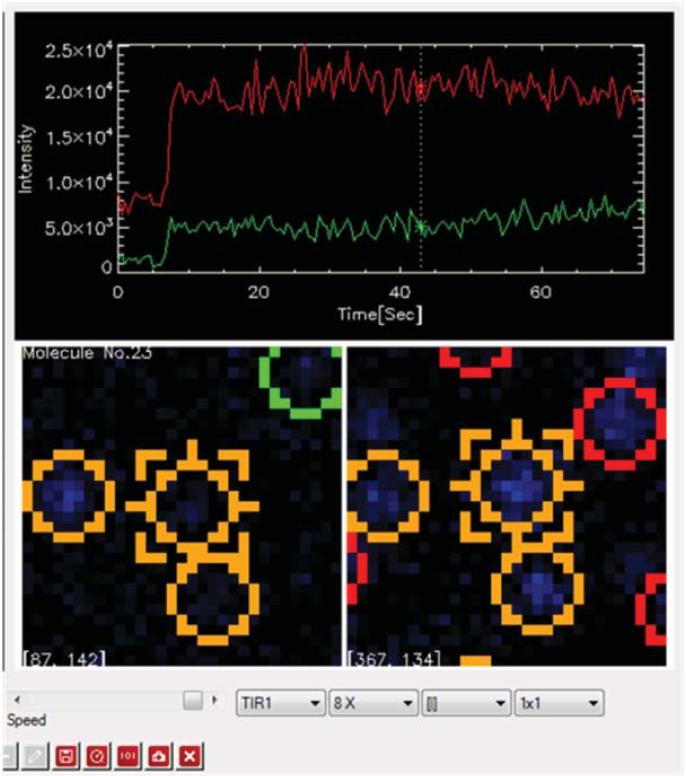

Representative time traces of content and lipid mixing events for a fluorescent spot that corresponds to a single interacting vesicle pair. Green (lower) and red (upper) lines are the fluorescence intensity time traces of content and lipid dyes, respectively. Time point 0 indicates the instance of Ca2+ buffer injection. The time binning used in this particular experiment was 200 msec. (a) Immediate full fusion. (b) Delayed full fusion. (c) Hemifusion only.

Our single vesicle-vesicle system starts from a metastable state of docked vesicle pairs that is established by incubation periods at zero Ca2+ concentration14. The incubation periods at zero Ca2+ are followed by Ca2+ injection at a defined concentration. Our system thus mimics the arrival of a stepwise Ca2+ concentration increase that acts on the readily-releasable pool of primed synaptic vesicles. This stepwise Ca2+ concentration increase is reminiscent of photolysis of caged Ca2+ experiments in neurons that are typically also carried out at ambient temperature27,28. In principle, our system is suitable for studies at other temperatures as well, although the stability of the vesicles need to be carefully checked at elevated temperature. Furthermore, our system should be extendable to a different Ca2+ delivery method in order to mimic transient Ca2+ concentration increases that are typical for physiological neurotransmitter release. On a different note, our incubation period at zero Ca2+ should reduce cis-interactions between the C2 domains of synaptotagmin to its own membrane that otherwise might prevent proper trans-interactions with acceptor vesicles in assays that use a constant non-zero Ca2+-concentration29.

Optical tweezer pulling experiments recently revealed a partially folded intermediate of the SNARE complex under external force conditions30. This intermediate likely facilitates the metastable state of interacting, but mostly unfused, vesicles during the incubation periods at zero Ca2+ in our assay. Indeed, during the incubation periods, we observed the formation of parallel trans SNARE complex interactions at the N-terminal ends of the SNARE complex14. Previous work from our laboratory showed that only a relatively small fraction (1/5th) of reconstituted SNAREs form stable anti-parallel configurations when they juxtapose membranes13; this should not be confused with the observation that soluble SNARE fragments (i.e., not reconstituted into membranes) can form a much larger fraction of unstable anti-parallel complexes in addition to the stable parallel SNARE complex31. Thus, we conclude that the majority of trans SNARE complexes are in a parallel, partially folded conformation in the metastable starting state of our single vesicle-vesicle system.

We observed that the majority of interacting vesicles formed hemifusion-free point contacts after the incubation periods, although a significant fraction had undergone hemifusion with reconstituted full-length SNAREs and synaptotagmin 118. Only a small fraction of vesicles underwent spontaneous (complete) fusion during the incubation period at ambient temperature. Upon Ca2+ injection, subsequent instances of fusion and hemifusion of these interacting, but not yet (hemi-) fused vesicles, could be distinguished and their temporal sequence monitored on a sub-hundred millisecond time scale14,18 (Fig. 4).

Here, we describe the detailed protocol of our original single vesicle-vesicle fusion system. However, recent improvements and modifications18 are also briefly mentioned.

Comparison to other methods

There are a number of advantages of our single vesicle-vesicle microscopy system compared to all other single vesicle assays known to us (Table 1). The unique features of our system are:

Triggering of fusion processes by Ca2+ or other factors. To our knowledge, our single vesicle-vesicle system is to-date the only one that starts from a metastable state of interacting vesicles that have been incubated at zero Ca2+, mimicking primed synaptic vesicles prior to an action potential.

Monitoring of the arrival of the Ca2+ buffer in the evanescent field by using a third spectrally distinct dye. Using this approach we showed that the rise time of the time-dependent content mixing probability upon Ca2+-injection is faster than 100 msec14. One can therefore use the first occurrence of any content mixing event upon Ca2+ injection as an indicator for the arrival of Ca2+ in the evanescent field as we did in our most recent work18. Of course, at significantly faster time resolution, this simplified approach to determine Ca2+-arrival in the evanescent field needs to be reconfirmed.

Ability of buffer exchange during the incubation periods, and immediately prior or after the fusion process. This feature of our system allows one to introduce accessory proteins or regulators at different stages. It should be noted, however, that the content or lipid dye fluorescence intensities of the donor vesicles should be checked before and after buffer exchange to ensure that vesicles did not get dislodged. In our experiments we did not observe disruption of interacting vesicles upon buffer exchange.

Observation of the temporal sequence of both content and lipid mixing events between single vesicle pairs on a sub-hundred millisecond time scale.

Differentiation of docking, complete fusion, hemifusion between interacting vesicles, and leakage/bursting of vesicles. Docking is characterized by the appearance of a spot with faint lipid dye fluorescence intensity. Hemifusion is characterized by a sharp increase in lipid dye fluorescence intensity without content dye fluorescence intensity change. Complete fusion is characterized by a sharp simultaneous increase in both content and lipid dye fluorescence intensities, followed by a steady state. Leakage is characterized by a sharp jump and subsequent fast decay of content dye fluorescence intensity.

Table 1.

Single vesicle assays

| Reference | Content mixing marker | Lipid mixing marker | Full-length synaptotagmin 1 in donor vesicles | Distinguish docking from (hemi-)fusion | Starting from interacting vesicles | Ca2+ triggering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Diao et al., 201025,26 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Lee et al., 201022 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Karatekin et al., 201021,23 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Kiessling et al., 201032 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Cypionka et al., 200919 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Bowen et al., 200413 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

Applications of the method

We applied our single vesicle-vesicle microscopy system to mimic synaptic vesicle fusion with a minimal set of proteins: neuronal SNAREs, synaptotagmin 1, and complexin. Full-length constructs were used for all proteins. Upon Ca2+ injection we observed a fast fusion burst with a rise time faster than 100 msec14,18. In contrast, neuronal SNAREs alone produced only a lipid-mixing burst upon Ca2+-injection, but with little content mixing; the effect of Ca2+ in this SNARE-only case is likely caused by PIP2 in the acceptor vesicle membranes33. This example illustrates the importance of monitoring content mixing since lipid mixing can occur well before, or without, content mixing.

Our assay allows one to exchange buffer (e.g., change in Ca2+ concentration) and the addition of other synaptic factors without disrupting interacting vesicle pairs. Thus, our assay allows one to perform manipulations that are not easily achievable in vivo.

Limitations

In our initial studies we applied a relatively high Ca2+-concentration in order to test our system under a variety of conditions14. This was a reasonable strategy at an early stage of technique development and proof-of-principle studies. After improvements in optical instrumentation as well as protein expression and purification18, we recently have been able to routinely perform experiments at 250-500 μM Ca2+ which is close to the physiological concentration range (starting at 10 μM and saturating at several hundred μM) 34 and comparable to other recent in vitro experiments35,36.

For the single vesicle lipid-mixing experiments (i.e., no content mixing monitoring) by Lee, et al.22, with reconstituted SNAREs and synaptotagmin 1, significantly higher PIP2 and synaptotagmin concentrations were used than in our experiments. Specifically, Lee, et al.22 used 6 mol% PIP2; in contrast we used 3.5 mol% in our experiments, consistent with measurements of PIP2 in the plasma membrane of PC12 cells37). Furthermore, a 1:1 molar ratio of synaptotagmin to synaptobrevin was used with a protein to lipid ratio of 1:200 for reconstitution into liposomes by Lee et al.22; in contrast we used a 1:4.6 molar ratio of synaptotagmin to synaptobrevin with a synaptobrevin protein to lipid ratio of 1:200 in our reconstitution protocol, consistent with observations of purified synaptic vesicles38. Furthermore, Lee al.22 performed experiments on mixtures of donor/acceptor vesicles in solution at a constant Ca2+ concentration, rather than starting from the metastable state of interacting vesicle pairs at zero Ca2+ in our assay. Perhaps the particular conditions used by Lee et al.22, as well as the possibility of synaptotagmin C2 cis-interactions with its own membrane when Ca2+ is present prior to docking of vesicles, caused the paradoxical decrease of Ca2+-triggered lipid mixing from 10 to 100 μM, assuming background level at 100 king of vesicles, a C2 or><Year>2010</Year><RecNum>534</RecNum><fusion (content mixing) as the Ca2+-concentration is increased.

Our initial studies14 did not allow us to determine the initial state (docked, hemifused, or fused) of individual vesicle pairs for the following reasons. (1) In order to perform several experiments in parallel on the same cover slip consisting of multiple channels (Fig. 3), the microscope stage was moved between data collection on individual channels. Our microscope stage was not precise enough to correlate the spots after the stage had been moved. (2) Moreover, the lipid dye fluorescence intensity of the vesicles showed variation due to differences in vesicle size and dye concentration in individual vesicles. Thus, the absolute lipid dye fluorescence intensity is not necessarily indicative of the particular initial state of the interacting vesicles.

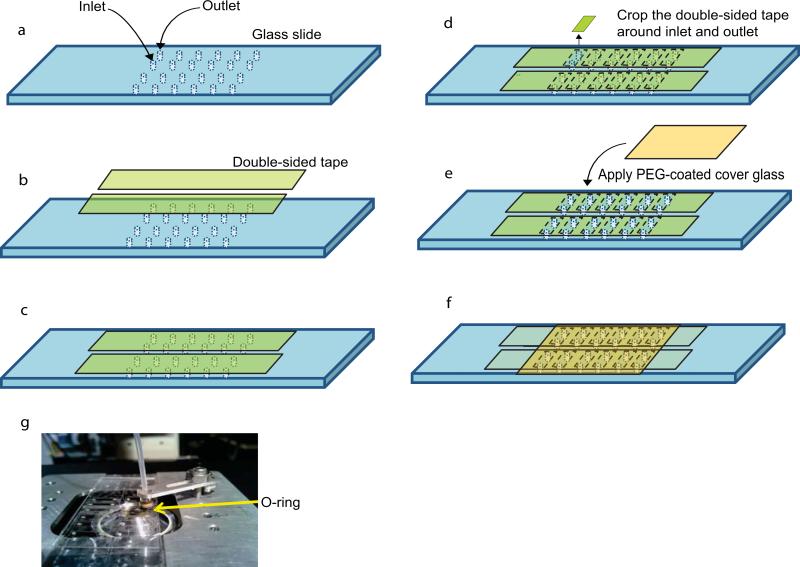

Figure 3.

Sample chamber and outlet ports. (a)-(f) Showing the preparation of the sample chamber. Inlet and outlet holes are initially covered by double-sided tape. (a-c) A rectangular piece of tape is cut out around the pairs of inlet and outlet holes to establish the area of the sample chamber. (d) A cover slip is added onto the top of the double-sided tape. (e) A total of 12 sample chambers with each ~ 2 μl volume can be accommodated with a single glass slide and cover slip. (g) A picture showing the outlet port of one of the sample chambers.

In order to determine the initial state of individual vesicle pairs prior to Ca2+ injection, we recently performed entire experiments (imaging of the vesicles right upon addition of donor vesicles to the tethered acceptor vesicles, incubation, Ca2+ injection, and observation) without moving the stage and switching the connecting tubes18. This alternative method allowed us to image the fluorescence intensities of both the content and lipid dyes right after mixing donor and acceptor vesicles, and then again right before Ca2+-injection, enabling the determination of any change in membrane state during the incubation period. However, since this method does not allow rapid switching between channels, all experiments had to be performed sequentially, increasing the total amount of time required for the experiments. We are working on further improvements and automation to routinely enable monitoring of the initial state of the individual vesicle pairs at the time of Ca2+-injection.

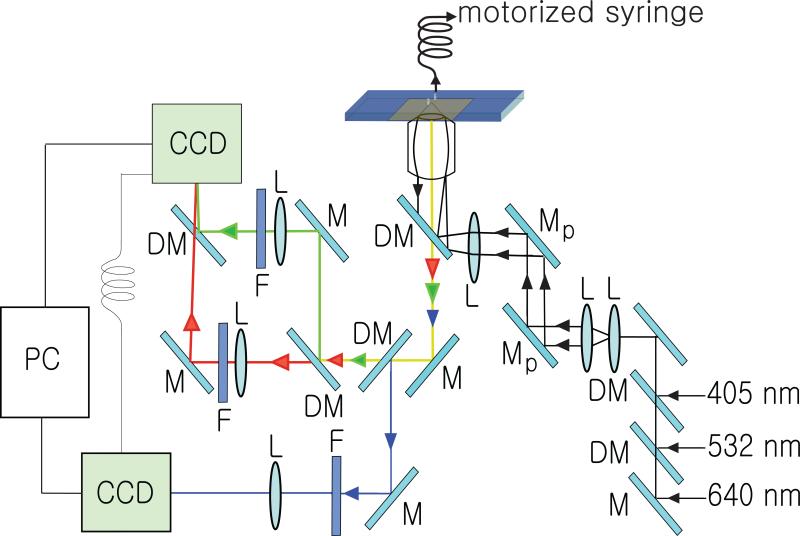

The minimum time binning that we were able to achieve with our original setup14 was 200 msec, effectively allowing the determination of rise and decay times greater than 100 msec. The limited time resolution of that particular setup was due to a poor signal-to-noise ratio of the fluorescence intensity time traces when time bins shorter than 200 msec were used even though the CCD camera that we used is capable of a time resolution of 30 msec. The poor signal-to-noise ratio in turn was related to the low laser power that was used to minimize photobleaching, along with the large number of optical elements in the fluorescence emission paths (Fig. 2). We are currently exploring simplifications of the optical apparatus in order to improve the time resolution for our assay; initial experiments enabled us to achieve sub-hundred millisecond time binning.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the objective-based TIR setup. The three-color excitation and emission paths are depicted. The evanescent field is created at the interface of the cover glass and buffer in the sample chamber. Abbreviations: M: mirror, DM: dichroic mirror, F: filter, L: lens, Mp: periscope mirror.

During the observation period we sometimes observed slow drifts of the content or lipid dye fluorescence intensities. Photobleaching is the most likely explanation for such drifts. For example, in Fig. 4b the lipid dye fluorescence intensity (red/upper line) slightly increases after the Ca2+ injection (time point zero), and then gradually decreases. In Fig. 4a, the content dye fluorescence intensity (green line) gradually increases over the observation period after Ca2+ injection. These gradual fluorescence intensity increases are related to the reduction of dye self-quenching by photobleaching. Initially, this will cause a slight increase in fluorescence intensity. At some point, photobleaching will dominate and then the fluorescence intensity gradually decreases. Ultimately, it is photobleaching that limits the useful time for continuous observation.

Experimental design

Protein expression and purification protocols for full-length synaptobrevin, syntaxin, SNAP-25, synaptotagmin 1, and complexin have been described in detail elsewhere14,18. Significant improvements of the protocols for syntaxin, synaptobrevin, SNAP-25, and complexin have been described elsewhere18. We simply refer to the purified samples as “Purified Synaptobrevin Solution”, “Purified Syntaxin Solution”, etc. (see Reagents).

Proteins were reconstituted into “acceptor” (syntaxin/SNAP-25) and “donor” (synaptobrevin/synaptotagmin 1) vesicles with a detergent depletion method as previously described14, and as detailed below. The homogeneity of reconstituted donor and acceptor vesicles obtained from this protocol was extensively tested with cryo-electron microscopy, light scattering, single molecule counting experiments to determine the protein number distributions in single vesicles, SDS gel electrophoresis of reconstituted vesicles, and determination of the orientation of reconstituted proteins as previously described14.

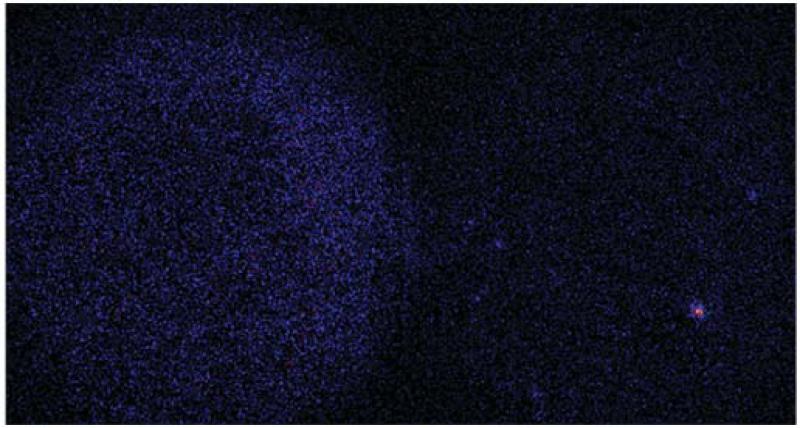

Full-length syntaxin /SNAP-25 reconstituted acceptor vesicles were immobilized on a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-containing surface via biotin-neutravidin tethers (Fig. 1a), as detailed below. Donor vesicles reconstituted with full-length synaptobrevin and synaptotagmin 1 were added to a sample chamber along with other factors, such as complexin (Fig. 1a), as detailed below. Non-specific binding of donor vesicles was very rare with our particular surface preparation, but should be tested for each new experimental setup by incubating the acceptor-free surface with donor vesicles (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Testing non-specific binding to the surface. The captured image shows a PEG-coated surface that was prepared by the protocol described in steps 1-14. The PEG-coated surface was incubated with donor vesicles for the same amount time as for experiments with acceptor vesicle-tethered surfaces and then washed with Vesicle Buffer (content mixing channel on the left side and lipid mixing channel on the right side). If the procedures of the PEG coating and surface preparation are successful one expects to only observe very rare non-specific binding of donor vesicles to the surface, and only background fluorescence, as shown in this figure.

The content and lipid dyes were at sufficiently high concentration in order to promote self-quenching of the fluorescence. We determined the optimum concentration of the dyes in order to achieve maximum sensitivity upon fusion (i.e., doubling of surface area or volume) by testing fluorescence intensities at various concentrations. We found that the optimum concentration ranges for the content dye sulforhodamine B and the lipid dye DiD were 50-100 mM and 3.5 – 4 mol% , respectively, for our system. We did not observe bursting or vesicle leaking, suggesting that the osmotic imbalance created by the aqueous content dyes does not pose problems for our particular vesicles with their lipid composition and protein to lipid reconstitution ratios.

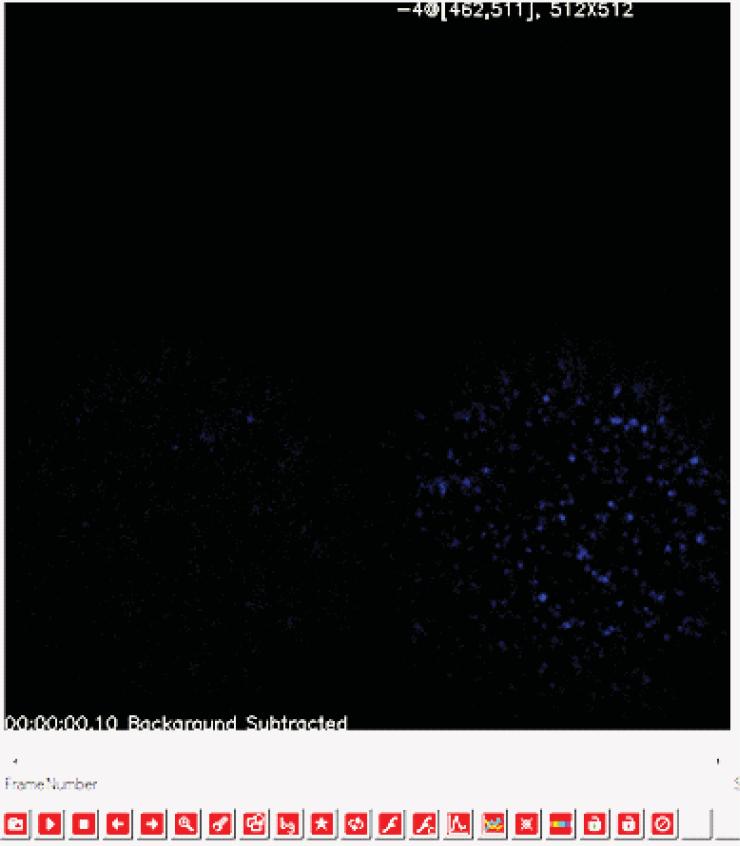

A first quick (seconds) incubation period followed where vesicles were allowed to interact via protein-protein interactions (Fig.1b). Excess donor vesicles were then removed by extensive buffer washing. Faint fluorescence spots were observed in the field of view originating from the self-quenched lipid dyes of docked donor vesicles. With a defined incubation time and acceptor vesicle concentration we were able to compare the interaction efficiency of donor and acceptor vesicles for different experiments by simply counting the number of spots, indicating donor vesicles interacting with acceptor vesicles. Donor-acceptor vesicle pairs were then incubated for a 30 min period at zero Ca2+ concentration in order to maximize the population of vesicles that were ready for Ca2+-triggered fusion (Fig. 1c). We observed that a shorter second incubation period decreased the number of vesicle pairs undergoing Ca2+ triggered fusion. The second incubation period may mimic priming of synaptic vesicles in the active zone. Other factors not yet present in our system may make this process faster in vivo.

The outlet of the flow chamber was then connected to a motorized syringe pump (as detailed below) with a fixed flow rate in order to perform buffer exchange. Several seconds prior to Ca2+ injection, we began to simultaneously monitor the fluorescence intensities from both the content and lipid dyes, as well as the blue dye that is part of the injected Ca2+ buffer. We continued monitoring for typically 30 to 50 seconds after Ca2+-injection (Fig. 1d). The fluorescence emissions from the three dyes were collected through an objective lens and projected onto two EM-CCD cameras. One camera simultaneously recorded both content and lipid dye fluorescence intensities using a dichroic beam splitter while a second camera monitored the blue dye fluorescence intensity upon Ca2+ buffer injection. One of the cameras was externally triggered by the other camera in order to allow simultaneous recording of all three fluorescence emissions. Analysis of the individual fluorescence intensity time traces was then carried out, as detailed below.

Because a single slide can accommodate twelve chambers, control experiments can be easily performed with the same slide. For example, four different experimental conditions could be tested in three channels with a single slide. For sufficient statistics, it is recommended that several hundred traces be analyzed that show fusion events; typically this requires more than three channels and two slides for our particular setup and experimental conditions.

Materials

Reagents

Sulforhodamine B (Invitrogen, cat. no. S1307)

Cascade blue ethylenediamine (trisodium salts) (Invitrogen, cat. no. C621)

Brain total lipid extract (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., cat. no. 131101C)

1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3',3'-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate, DiIC18(5), DiD (Invitrogen, cat. no. D307)

mPEG (MW 5000, mPEG-SCM, Laysan Bio, cat. no. mPEG-SCM-5000)

(3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) (Aldrich, cat. no. 440140)

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (sodium salt), DOPS (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., cat. no. 840035C)

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphoethanolamine, DOPE (Avanti Polar Lipid Inc., cat. no. 850725C)

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(cap biotinyl) (sodium salt), Bio-DPPE (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., cat. no. 870277X)

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, POPC (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., cat. no. 850457C)

Acetone (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. A929-4)

Biotin-PEG (MW 5000, Biotin-PEG-SCM, Laysan Bio, cat. no. biotin-PEG-SCM-5000)

Bio-beads™ SM-2 Adsorbent (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 152-3920)

β-mercaptoethanol, β-ME (Sigma, cat. no. M7154)

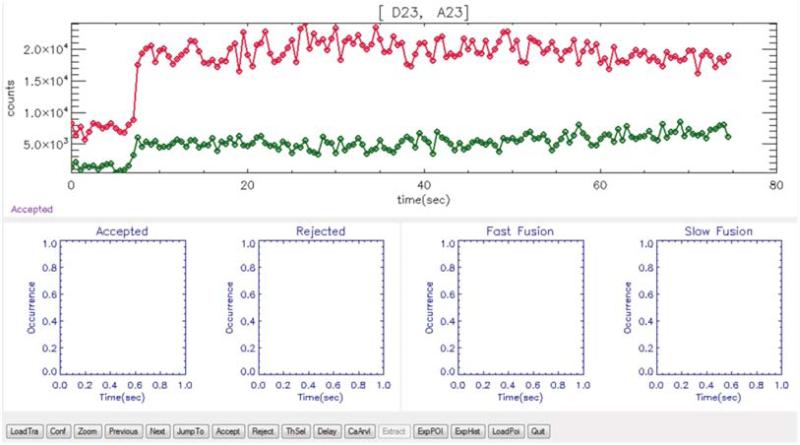

Chloroform (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. C606-1)

Cholesterol (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., cat. no. 70000P)

Fluorescent beads (200 nm, 625/645, Invitrogen, cat. no. F8806)

HEPES (RPI, cat. no. H75030)

L-α-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (Brain, Porcine-Triammonium salt), PIP2 (Avanti Polar Lipid Inc., cat. no. 8400046X)

NeutrAvidin (Thermo, cat. no .LF144746)

n-Octyl-B-D-glucopyranoside, OG (Affymetrix, cat. no. O311)

Sodium chloride, NaCl (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. BP358-1)

Tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (RPI, cat. no. T60040-5000.0)

CRITICAL:

All lipid reagents, mPEG and Biotin PEG have to be stored at -20 °C. (ii) Chloroform, acetone, β-mercaptoethanol need to be handled in a chemical hood.

Equipment

Motorized syringe pump (Cole Parmer, cat. no. KDS 210)

Dialysis cassettes (10-KDa MWCO, 3 ml, Thermo Scientific, cat. no. 66380)

Empty PD-10 disposable columns (GE Healthcare, cat.no. 17-0435-01)

Sepharose CL-4B (GE Healthcare, cat.no. 17-0150-01)

Double-sided tape (3M, cat. no. 20014958)

Forceps (Techni-Tool, cat. no. 35A-SA)

Glass coverslips (24 × 30 mm, No.1 1/2, VWR, cat. no. 48393 092)

Glass slides (1” × 3”, 1 mm thick; VWR, cat. no. 16004-430)

Gas tight syringe (5 ml, Hamilton, cat. no. 81520)

Nalgene® Polypropylene Straight-Sided Jars (VWR, cat. no. 36319-580)

Cover glass staining rack (Thomas Scientific, cat. no. 8542E40)

Aluminum foil

Beaker (500 mL)

Vacuum Desiccator

13×100 mm glass culture tubes (VWR, cat. no. 47729-572)

Magnetic stirrer

Microfuge tubes (Eppendorf, cat. no. centrifuge 5415 D)

Needle (26 gauge, 3/8”, BD, cat. no. 305110)

Parafilm (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 13-374-10)

Vacuum pump or house vacuum line

Vortex mixer (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 02215365)

Ferrule assembly (Upchurch Scientific cat. no. P-250)

Diamond point drill bits (Starlite cat. no. 115005)

Equipment setup

Objective based total internal reflection (TIR) fluorescence microscopy apparatus

Our three-color custom built, objective-based total internal reflection (TIR) fluorescence microscopy apparatus used a Nikon TE2000U inverted microscope (Nikon) (Fig. 2). Laser excitation paths for content and lipid mixing dyes (Excelsior 532 nm, Spectra-Physics, Newport and cube 640 nm, Coherent) and for the Ca2+ indicator dye (405 nm, Coherent) were combined with dichroic mirrors. The laser beams were expanded by a telescope and then focused to the back focal plane of the objective lens (Nikon Apo TIR 100×, 1.49 N.A.) by a converging lens with a focal length of 300 mm and delivered to the interface between the cover glass and the sample chamber for TIR. Fluorescence emissions were collected by the same objective lens and projected to two EM-CCD cameras (iXon EM+ DU-897, Andor Technology). The fluorescence emissions from sulforhodamine B and 1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3',3' tetramethylindodicarbocyanine were imaged with FF01-562/40 (Semrock) and HQ700/75m (Chroma Technology) optical band pass filters, respectively, with one of the two CCD cameras. The fluorescence emission from the cascade blue was separately imaged by an optical band pass filter (FF01-417/60, Semrock) with the second CCD camera.

Attachment of tubes to outlet ports

A tube was attached to the outlet port of the flow chamber by decorating the end of the tube with a small rubber O-ring (ID 3/64 inch, OD 9/64 inch) that was just large enough to cover the outlet ports on the slide (Fig. 3). An O-ring (yellow arrow) was glued to a ferrule (Upchurch Scientific part P-250) tightly locked on the 1/16 inch OD tubing with a stainless steel lock ring. A custom machined thin metal clamp was used to hold the ferrule-tube-O-ring assembly to the outlet port.

Reagent setup

Sulforhodamine Buffer (pH 7.4, 50 mM sulforhodamine B, 20 mM HEPES, 90 mM NaCl, 110 mM OG, total volume 2 ml)

Vesicle Buffer (pH 7.4, 20 μM EGTA, 90 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 1 % β-ME, total volume 2.5 L, for vesicle preps and dialysis)

PEG Buffer (pH 8.6, 0.5 M potassium sulfate, 50 mM sodium phosphate, 1 to 99 ratio of Biotin-PEG to mPEG, total volume 5 ml)

OG Buffer (pH 7.4, 110 mM OG, 20 μM EGTA, 90 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 1 % β-ME, total volume 500 ml)

Fluorescent Beads Buffer (pH 8, 10 mM TRIS-HCl and 50 mM NaCl, total volume 1 ml)

CRITICAL:

Except for the Fluorescent Beads Buffer, all buffers must be freshly prepared and used within a day.

Acceptor Vesicle Lipid Mixture: Brain total lipid extract (see Reagents) supplemented with 20 mol% cholesterol, 3.5 mol% PIP2, and 1 mol% biotinylated phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). The PIP2 concentration that we used (3.5 mol%) is within the range of that observed in the plasma membrane of PC12 cells37. Make a solution of 33 mM lipids mixture in 100 μl chloroform.

Donor Vesicle Lipid Mixture: phosphatidylcholine (44.5 mol%), PE (20 mol%), phosphatidylserine (12 mol%), cholesterol (20 mol%), DiD (3.5 mol%). Make a solution of 33 mM lipids mixture in 100 μl chloroform.

CRITICAL:

All mixtures must be freshly prepared.

Purified Synaptobrevin Solution: 100 μM purified full-length protein in 165 μl OG Buffer)

Purified Syntaxin Solution: 60 μM purified full-length protein in 275 μl OG Buffer)

Purified SNAP-25 Solution: 150 μM purified full-length protein in 687.5 μl Vesicle Buffer)

Purified Synaptotagmin Solution: 40 μM purified full-length protein in 100 μl OG Buffer)

Purified Complexin Solution: 100 μM purified full-length protein in 500 μl Vesicle Buffer)

CRITICAL:

(i) Protein solutions must be freshly prepared and used within 1-2 hours after the final purification step. (ii) Do not exceed the specified protein concentrations, especially for synaptotagmin, since otherwise proteins may aggregate and Ca2+-triggered content may not occur. (iii) For all constructs with his-tags ensure that tags are completely cleaved by performing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide (SDS-PAGE) gel electrophoresis before and after cleavage. (iv) Ensure that proteases used for cleavage have been completely removed or inactivated.

Procedures

Glass surface preparation and PEG coating

Note: a similar protocol has been published elsewhere26 along with an instructional movie at http://bio.physics.illinois.edu/movies/PEG%20protocol/.

Place cover glasses in a staining rack and immerse the rack in the acetone, holding it with Nalgene® polypropylene straight-sided jars.

Close the lid of the jars to avoid the evaporation of acetone during sonication.

Sonicate the cover glass rack for ~1 hr in acetone more than three times. Use fresh acetone every time.

Move the cover glass rack to a new jar, add 3-5% APTES solution in acetone to the jar and incubate the cover glasses for 30 min in the dark. Close the lid to avoid the evaporation of acetone.

Wash the cover glasses with clean acetone at least 3 times. Do this by preparing three fresh acetone jars and gently shake the rack holding the cover glasses in each jar for several minutes.

Wash individual cover glasses with deionized water and acetone.

Dry them with filtered N2.

Prepare a humidity chamber. Add 5 to 10 ml of water to an empty pipette tip box. Do not remove the tip holder insert that has a flat surface.

Place the cover glasses onto the top of the tip holder insert.

Drop 70 μl of 10% (w/v) PEG Buffer in pH 8.6 sulfate buffer (0.5 M potassium sulfate and 50 mM sodium phosphate) on the cover glasses.

Make “sandwiches” of pairs of cover glasses with the PEG drops pointing inside. This will ensure a uniform surface coverage of PEG. It is important to prevent the formation of bubbles between the two cover glasses.

Cover the humidity chamber with the lid of the tip box and incubate cover glasses for 2 hrs inside a humidity chamber. Wrap the humidity chamber with aluminum foil to keep the cover glasses in the dark.

Separate the sandwiched pairs of cover glasses and thoroughly wash cover glasses with clean deionized water and store them in deionized water at 4 °C.

Prior to use, dry cover glasses with filtered air or N2.

Sample chamber preparation (Fig. 3)

-

15

Drill holes with diamond point drill bits (see Equipment) in glass slides for inlets and outlets (Fig. 3a).

-

16

Apply double-sided tape to clean slide glass and cut out rectangular shapes around inlet and outlet holes (Figs. 3b-d).

-

17

Apply a dried PEG-coated cover glass to the double-sided tape on the glass slide (Fig. 3e). It is important to make sure that (i) the PEG coated side faces to the interior of the sample chamber; (ii) both the cover glass and glass slide are completely attached to the double-sided tape so that no water can leak from the chambers (a good seal should last for a couple of days). Up to 12 sample chambers can be accommodated with one glass slide.

Fluorescent bead sample for calibration of the microscopy apparatus

-

18

Inject the Fluorescent Beads Solution into an assembled sample chamber until it is completely filled. Start with a 1000 × dilution of the fluorescent bead slurry as provided by the manufacturer. If necessary, adjust the concentration of the bead solution.

-

19

Remove excess fluorescent beads by rinsing with buffer if necessary. The surface density of the beads needs to be low enough to locate and image individual beads. <PAUSE POINT> The fluorescent beads sample can be kept over several weeks unless the buffer inside the bead sample chamber dries out. The same bead sample can be used for multiple experiments.

Acceptor vesicle preparation

Note: an instructional video is available as supplementary material (will be supplied later).

-

20

Add 100 μl of the Acceptor Vesicle Lipid Mixture to a glass tube and wrap the glass tube with aluminum foil.

-

21

Evaporate the chloroform in the glass tube using a gentle stream of N2 gas.

-

22

Further dry the lipid film by placing glass tube in the vacuum desiccator for 2 to 12 hours.

-

23

Apply 275 μl Purified Syntaxin Solution onto the dried lipid film in the bottom of the glass tube. The protein to lipid molar ratio can be varied from 1:200 to 1:2000 by changing the protein concentration. We typically used a protein to lipid molar ratio of 1:200 for the acceptor vesicles in our experiments14,18. Determine the protein concentration by a reliable assay, e.g., UV absorption at 280 nm or a Bradford assay. The molar ratio between OG to lipids should be 8.5 ~ 12 (e.g. 100 μl of 33 mM lipid solution to 350 μl of 110 mM OG Buffer). The critical micelle concentration (CMC) of OG is 23 – 25 mM.

-

24

Dissolve the lipid film with the syntaxin containing solution from step 23 by vortexing it at a low speed that does not create bubbles.

-

25

After the solution in the glass tube is cleared, apply Vesicle Buffer to the lipid-protein mixture. The volume of Vesicle Buffer should be 1.5 times of the total volume of the lipid-protein mixture at step 24. While applying Vesicle Buffer into the tube, fast vortexing is necessary in order to prevent local concentration gradients.

-

26

Apply 550 μl SNAP-25 solution to the glass tube while fast vortexing it to prevent local concentration gradients. Notes: (i) The total volume of the resulting solution should be 2 times of the total volume of the lipid-protein mixture at step 24; (ii) the molar ratio of SNAP-25 to syntaxin should be more than 5; and (iii) the combined volume of Vesicle Buffer and SNAP-25 solution should be large enough to dilute the OG concentration below the CMC.

-

27

Incubate the solution at room temperature for 15 min.

-

28

Pass the sample solution through a CL-4B column (Mr = 104 - 107) in order to remove detergents, excess of SNAP-25, and other impurities from the protein-lipid-detergent mixture. The CL-4B column must be be pre-washed and pre-equilibrated with Vesicle Buffer prior to use. The size of the CL-4B column depends on the volume of protein-lipid-detergent mixture. For example, for a volume of 200 – 400 μl, a 5 ml CL-4B column should be used. Vesicle Buffer is used as eluent after the sample solution has entered the stationary volume of the column.

-

29

Collect the void volume eluate from the column that is expected to contain the vesicles. The void volume should appear as an opaque solution due to light scattering of the vesicles.

-

30

Dialyze the vesicle solution in a 10-KDa MWCO dialysis cassette against Vesicle Buffer overnight at 4 °C in order to further remove any residual OG from the vesicle solution. For 1 ml of vesicle solution, use 500 ml of Vesicle Buffer. For every 500 ml of vesicle solution, add 0.5 g of Bio-beads powder.

CRITICAL:

Use different dialysis beakers for acceptor and donor vesicles to avoid cross-contamination.

-

31

Check the approximate protein incorporation ratio in vesicles by performing SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis of the vesicle solution and staining the gel with Coommassie blue. Initially, load 20 - 50 μl of vesicle solution in the gel. If the protein bands are too faint or overloaded, adjust the volume and rerun the gel. For the expected result, see Fig. S6A, left lane, in ref.14. The syntaxin to SNAP-25 ratio should be close to 1:1.

CRITICAL:

Ensure that reconstituted proteins are not degraded. Use acceptor vesicles within 1 to 2 days after reconstitution. It is recommended to the repeat the SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis of the vesicle solution right before using the vesicles in microscopy experiments.

-

32

It is recommended to check the vesicle size distribution with dynamic light scattering and/or cryo-EM imaging, the protein number density, and the proper orientation as previously described14 (see also Figs. S3, S4, and S6 in that reference). The diameter of vesicles and the average size of the lipids can be used to calculate the number of lipids in single vesicles as follows: The total number of lipids in a single vesicle is 4π(d/2)2/a+4π((d-t)/2)2/a where d is the diameter of a single vesicle (typically ~ 70 nm for the vesicles prepared with this protocol), a is the average cross-sectional area of a single lipid (70 Å2), and t is the typical thickness of a lipid bilayer (5 nm).

Donor vesicle preparation

Note: a instructional video is available as supplementary material (will be provided later).

-

33

Add 100 μl Donor Vesicle Lipid Mixture into a glass tube and wrap the glass tube with aluminum foil.

-

34

Evaporate the chloroform in the glass tube using a gentle stream of N2 gas.

-

35

Keep the dried lipid film in the glass tube in the vacuum desiccator for 2 to 12 hours. Wrap the desiccator with aluminum foil.

-

36

Mix Purified Synaptobrevin Solution (165 μl) and Purified Synaptotagmin Solution (100 μl) at a 4.6:1 molar ratio, as consistent with observations on purified synaptic vesicles 38.

-

37

Dissolve sulforhodamine B into the synaptobrevin and synaptotagmin solution from step 36 in order to achieve 50 mM final concentration of sulforhodamine B.

-

38

Apply the solution from step 37 to the dried lipid film. Note that (i) the synaptobrevin to lipid molar ratio can be varied from 1:200 to 1:2000 by changing the protein concentration (determine the protein concentrations by a reliable assay, e.g., UV absorption at 280 nm or a Bradford assay); and (ii) the molar ratio between OG to lipids should be 8.5 ~ 12 (e.g. 50 μl of 66 mM lipids solution to 350 μl of 110 mM OG Buffer). We typically used a synaptobrevin to lipid molar ratio of 1:200, as consistent with observations on purified synaptic vesicles 38.

-

39

Dissolve the lipid film with protein solution by vortexing it at a low speed that does not create bubbles.

-

40

After the lipid film is dissolved, apply Vesicle Buffer with 50 mM sulforhodamine B into the lipid-protein mixture. The volume of Vesicle Buffer should be 3.5 times of the total volume of the lipid-protein mixture at step 39, and should be large enough to dilute the OG concentration below the CMC. Fast vortexing is necessary while applying the Vesicle Buffer.

-

41

Pass the sample solution through a CL-4B column in order to remove detergents and other impurities from the protein-lipid-detergent mixture and in order to remove free sulforhodamine B dyes that are not encapsulated in vesicles. Vesicle Buffer is used as eluent after the sample solution has entered the stationary volume of the column.

-

42

Collect the void volume eluate from the column.

-

43

Dialyze the vesicle solution in a 10-KDa MWCO dialysis cassette into 1 L of Vesicle Buffer overnight at 4 °C. For 1 ml of vesicle solution, use 500 ml of Vesicle Buffer. For every 500 ml of vesicle solution, add 0.5 g of Bio-beads powder.

CRITICAL:

Use different dialysis beakers for acceptor and donor vesicles to avoid cross-contamination.

-

44

Check the protein incorporation ratio in vesicles by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and by staining the gel with Coommassie blue. Initially, load 20 - 50 μl of vesicle solution in the gel. If the protein bands are too faint or overloaded, adjust the volume and rerun the gel. For the expected result, see Fig. S6C, right lane, in ref.14. The synaptobrevin to synaptotagmin ratio should be close to 4.6:1.

CRITICAL:

Ensure that proteins are not degraded, and no SDS-resistant bands for oligomerized synaptotagmin are visible. Use donor vesicles within 1 to 2 days after reconstitution. It is recommended to repeat the SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis of the vesicle solution right before using the vesicles in microscopy experiments.

-

45

It is recommended to check the vesicle size distribution with dynamic light scattering and cryo-EM, the protein number density, and proper orientation as previously described14 (see also Figs. S3, S4, and S6 in that reference).

Immobilization of acceptor vesicles

-

46

Manually inject ~ 5 μl solution of 0.5 mg/ml neutravidin in Vesicle Buffer into the sample chamber.

CRITICAL:

Do not introduce bubbles into sample chambers when solution is injected.

-

47

Incubate for 15 min at ambient temperature.

-

48

Thoroughly wash the sample chamber with 100 – 200 μl of Vesicle Buffer.

-

49

Manually inject ~ 30 μl of a mixture of acceptor vesicles (from steps 20-32) and protein-free vesicles at a ratio of 1:4 into the sample chamber. Protein-free vesicles are prepared with the same vesicle preparation method as the acceptor vesicles except that no proteins are present in the OG Buffer. The presence of protein-free vesicles reduces the density of the acceptor vesicles on the surface; this is desirable in order to optically resolve individual vesicles.

-

50

Incubate the system from step 49 for 30 min at ambient temperature.

-

51

Thoroughly wash out excess vesicles with 100 – 200 μl of Vesicle Buffer. Any soluble accessory proteins (e.g., complexin) can be added at this step if necessary.

First incubation period

-

52

Manually inject ~ 20 - 30 μl of donor vesicle containing solution (from steps 33-45) into the sample chamber. Soluble accessory proteins (e.g., complexin) can be added together with the donor vesicles if desired. For example, add 10 μl of the 100 μM Purified Complexin Solution to 190 μl of the donor vesicle solution in order to achieve a final concentration of 5 μM complexin in the vesicle mixture.

CRITICAL:

(i) If the soluble accessory proteins are added at step 51, then add the proteins to the donor vesicle containing solution as well (from steps 33-45) to keep the same concentration of the proteins in the sample chamber. (ii) The concentration of donor vesicles needs to be optimized in order to achieve enough separation between donor vesicles to be optically resolved (see below). If necessary, the donor vesicle solution (from steps 33-45) should be diluted.

-

53

Incubate for 10-30 sec.

-

54

Thoroughly rinse the sample chamber with 100 – 200 μl of Vesicle Buffer.

CRITICAL:

If soluble accessory proteins are added in steps 51 and 52, then make sure that these proteins are also added to the Vesicle Buffer rinsing step 54 in order to maintain the same concentration of the proteins in the sample chamber.

Second incubation period

-

55

Incubate the donor vesicles that are interacting with acceptor vesicles (from step 54) for 30 min at room temperature without laser illumination.

Alignment of excitation/imaging paths and outlet port

-

56

Check that the green, red and blue lasers are aligned correctly. Ensure that (i) the individual laser beams are impinged to the same area of the sample plane; (ii) the laser beams are producing TIR at the interface between the buffer and cover glass; and (iii) the optical elements in the imaging paths are properly aligned.

-

57

Place the bead-mapping sample (from steps 18-19) in the sample stage. Image the beads using both the content and lipid dye fluorescence emission paths.

-

58

Ensure that the EM-CCD camera monitoring the calcein dye fluorescence intensity is externally triggered by the other CCD camera.

-

59

Align the emission paths for both content and lipid dyes. The images of both dyes should be identical.

-

60

Take several images of the bead sample.

-

61

Compute bead locations in both content and lipid channels to sub-pixel accuracy by our custom program written for the IDL graphic system (ITT Visual Information Solutions). Follow steps 81-86 in the Data Analysis Section for the bead mapping process. If the program fails to provide a bead-mapping coefficient, then redo the alignment (steps 56-60 and 81-86).

-

62

Locate the desired sample chamber prepared from step 55.

-

63

Check the syringe in the motorized pump. Make sure that there is no bubble in the tubing.

-

64

Place an O-ring at end of the tubing onto the top of the outlet of the sample chamber and tighten the pin to obtain a good seal between the O-ring and the slide glass surface (Fig. 3).

-

65

Turn on all lasers.

-

66

Start the “live” mode in the acquisition software (Andor Solis, Andor Technology) to check the lipid and content dye fluorescence intensity imaging channels and the focus.

-

67

Adjust ND filters to reduce photobleaching.

Ca2+ injection

-

68

Gently apply a 40-50 μl drop of Vesicle Buffer on the top of the inlet hole and draw the buffer into the sample chamber using the motorized syringe connected to the outlet hole (Fig. 3g). To do this, adjust the syringe speed to 20-30 μl/sec. Check whether there is any leakage. Wipe off excess buffer with paper tissue.

CRITICAL:

Do not press on the cover slide or perturb the sample when applying the Vesicle Buffer drop, or when removing the residual buffer after injection.

-

69

Ensure that the focus is still maintained before and after drawing the Vesicle Buffer. If it has drifted, then adjust the pressure to the O-rings and redo steps 64-66.

-

70

Start data acquisition on both two CCD cameras with all lasers turned on. Check that photobleaching is minimal.

-

71

~ 5 seconds after data collection has started, place a drop of Ca2+ solution (at the desired Ca2+ concentration in Vesicle Buffer) onto the inlet and draw it into the sample chamber immediately with the motorized syringe.

-

72

Save movies of fields of view for both content and lipid dye detection channels as “sif” files.

Data analysis

Procedures for content and lipid dye fluorescence intensity time trace generation and dual color image registration by bead mapping are similar to what is commonly used for single molecule FRET data analysis39,40, multi-color super-resolution imaging41,42, as well as other single vesicle assays26. The following step-by-step guide uses custom IDL programs adapted from previous single molecule FRET work40. These custom IDL programs are available at http://cns-online.org/wiki/index.php/File:Software_for_nature_protocol.zip Note, that each frame of the CCD camera (512 × 515 pixels) is analyzed as two individual 256×512 frames that are horizontally next to each other (corresponding to the recorded fluorescence emissions of the content and lipid dyes, respectively).

-

73

Identify vesicles in both content and lipid dye channels by finding fluorescent spots with peaks well above background in the “sif” movie files using the custom IDL program. Load a movie file into TIR 2007 by clicking the “load” button (Fig. 6).

-

74

Register the spots in both channels by applying the 2D polynomial mapping produced by step 61. If the fluorescence intensity of the spot is too weak in one of the channels, use the position predicted from the transformation instead. i) Load the mapping coefficient by clicking the “load mapping coefficient” button. Start the movie by clicking the arrow button on the window and stop the movie after Ca2+ injection. ii) Click the “find peaks” button to select spots in the field of view.

-

75

Generate fluorescence intensity time traces for each spot in both channels by integrating a fixed number of pixels around each spot. The pixels to be integrated are centered at the centroid of the spot. i) Click the button with a tooltip that reads “Calculate full traces”. The calculated fluorescence intensity time traces of an individual spot will show up on the upper right-hand side panel (Fig. 7).

-

76

For each spot visually identify and record fluorescence intensity jumps in both content and lipid dyes fluorescence intensity time traces using the custom IDL program. i) Load the trace into the “Fusion09” program (Fig. 8). ii) Navigate through individual traces via the “previous”, “next”, “jumpto” buttons. iii) Use the “accept” and “reject” buttons to reject traces containing no information. iv) Double-click a trace plot in order to activate or deactivate the particular trace plot of a channel. v) When a channel is activated, <ctrl> plus left mouse click where an intensity jump occurs in order to record such an event. Only accept jumps that are larger than the average noise level of the trace before and after the jump (, where σ1 and σ2 are the standard deviations before and after the jump, typically measured over 5-10 time points). In other words, jumps should only be accepted with a signal-to-noise ratio greater than 1. Hold <ctrl> and tweak the mouse cursor position before releasing the left mouse button. To cancel the event, right-click the mouse.

-

77

Load the movie obtained from the cascade blue (Ca2+) channel by clicking the “CaArv” button of the “Fusion09” program. The program automatically generates cascade blue fluorescent intensity traces by integrating a fixed region of interest (64x64 pixels) at the center of the field of view. It also automatically identifies and records the intensity jump in the blue trace. The blue intensity jump identifies the instance of the Ca2+ delivery to the field of view.

-

78

Export recorded events (i.e., fluorescence intensity jumps) from the “Fusion09” program as a csv file. Each line of the csv file contains the recorded events from a particular fluorescence intensity time trace. The comma-separated line begins with the content ID followed by the time points of the recorded events and followed by the acceptor lipid ID and the time points from the acceptor trace. Note that there are six fields for each channel reserved for recorded jumps, and an empty field indicates that there were no more jumps identified. We expect at most one jump event per trace for most of the traces.

-

79

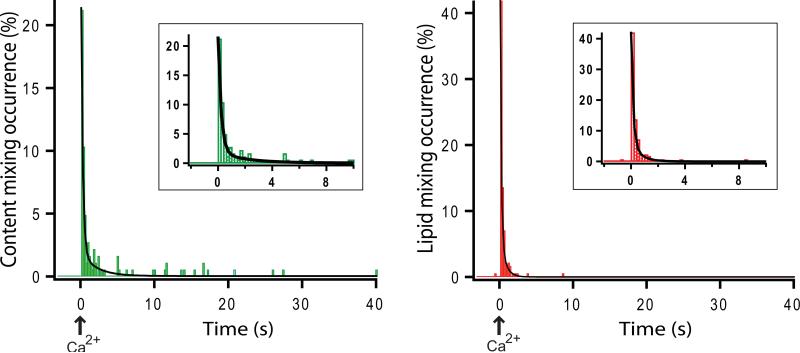

Define time “0” as the time bin when the blue fluorescence intensity jump occurs. Generate histograms of content and lipid mixing events using the time binning chosen for the experiment.

-

80

Fit single or double exponential decay functions to the histograms using programs such as IGOR Pro (Wavemetrics, Inc.) or ORIGIN (OriginLab, Inc.). Extract time constants and amplitudes of each population.

Figure 6.

Screenshot of an image series (movie) loaded into our custom IDL program.

Figure 7.

Display of an example of a fluorescence intensity time trace.

Figure 8.

Display of time points of content and lipid mixing events.

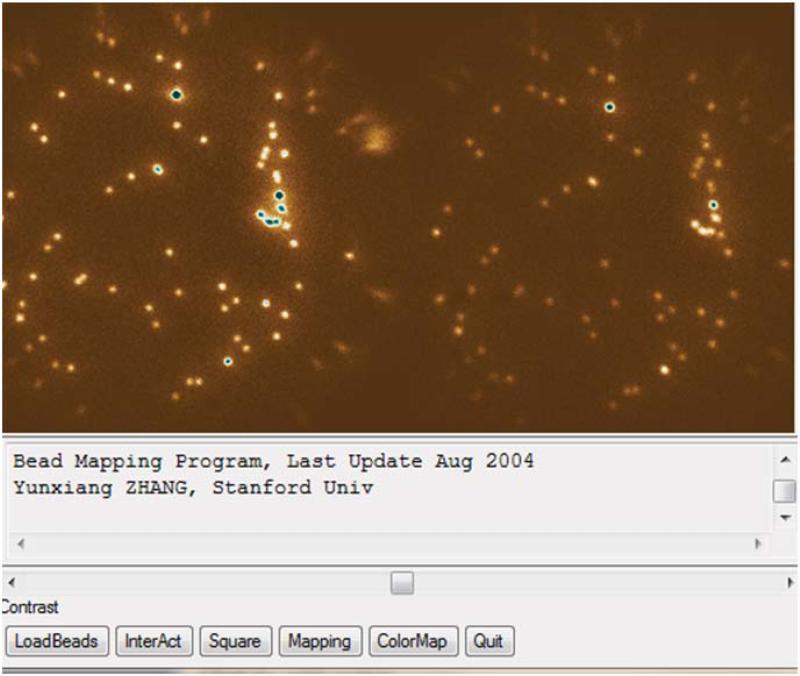

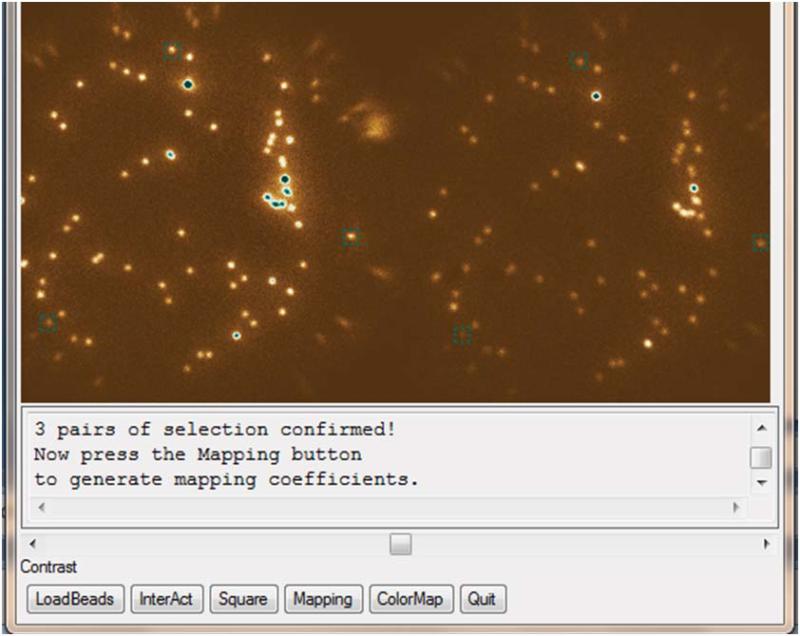

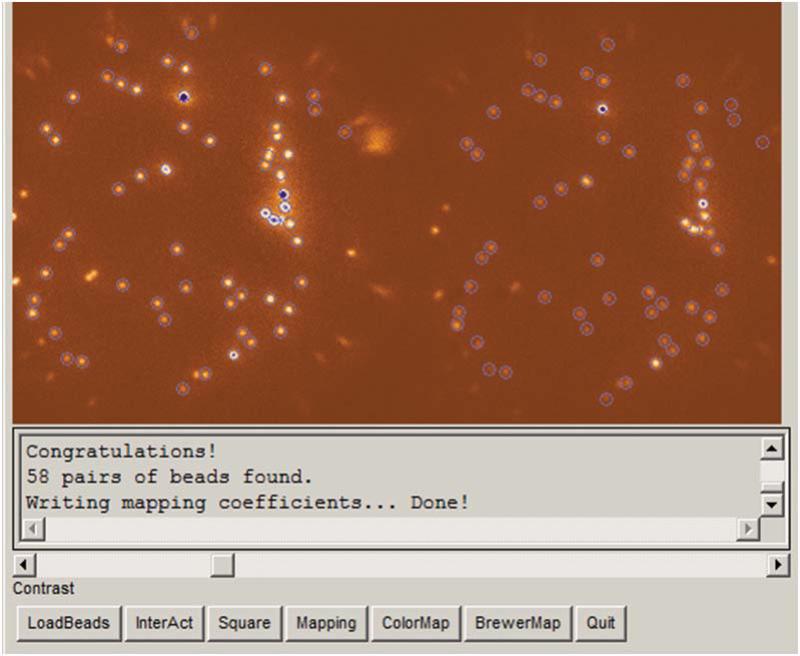

Bead mapping

-

81

Load an image of a bead sample (Fig. 9).

-

82

To select three desired bead pairs from the loaded image click “InterAct” in the window. Locate the cursor on the top of a bead and click. Then a square will be positioned on the bead.

-

83

Locate the bead on the center of the square by using the arrow buttons on the keyboard for the content channel on the left side. To register both channels, find the matching bead and locate the second square on the top of it. Holding the <ctrl> key while using arrow buttons will allow you to move the second square for the lipid channel.

-

84

Once one pair of beads is identified by the two squares accordingly press the space bar.

-

85

Find and register two more pairs of beads that are non-collinear and separated as much as possible in the given field of view (Fig. 10).

-

86

Click on the “mapping” button on the window. The mapping coefficient (xx.coe) will then be automatically saved in the directory folder that contains the bead image (Fig. 11).

Figure 9.

Image of loaded beads.

Figure 10.

Selection of pairs of beads.

Figure 11.

Generation of the bead mapping coefficient.

Timing

Step 1-8 Cleaning cover glass; ~ 5 hours

Step 9-14 PEG coating of cover glass: ~ 4-5 hours

Step 15-17 Sample chamber assembly: ~ 1-2 hours

Step 18-19 Fluorescent bead sample for bead mapping: ~ 10-30 min

Step 20-45 Acceptor and donor vesicles preparation including dialysis time: 18 hours

Step 46-51 Immobilization of acceptor vesicles: ~ 1 hour

Step 52-55 Incubation of donor vesicles: ~ 40 min

Step 56-74 Measurement for a single slide: ~ 1 hour

Step 73-86 Data analysis for a single slide: ~ 10 hours

Anticipated results

Prior to Ca2+ injection, the content and lipid dye fluorescence intensities for each observed spot are expected to be relatively constant. After Ca2+ injection, statistically significant jumps in lipid and content dye fluorescence intensities are expected to occur at certain times for each spot depending on the experimental conditions and factors included in the system (Fig. 4, see also step 76). The fluorescence intensities should be relatively constant before and after each jump although slow gradual drifts are sometimes observed due to photobleaching, as also mentioned in the Limitations Section. The fluorescence intensity jumps can be used to classify events into immediate fusion, delayed fusion, or hemifusion of individual vesicle pairs. We define “immediate” fusion by a jump in content dye fluorescence intensity at the instance of Ca2+ injection, and “delayed” fusion by a content dye fluorescence intensity jump at some later time after Ca2+ injection; in both cases the content dye fluorescence intensity jump is generally associated with a lipid dye fluorescence intensity jump although there may be a few cases when the lipid dye fluorescence intensity jump is small due to noise or prior photobleaching. Hemifusion is characterized by a lipid dye fluorescence intensity jump without a corresponding content dye fluorescence intensity jump (Fig. 4c). Vesicle leakage can be easily distinguished from genuine fusion events since they lead to a small rapid increase, followed by a rapid complete decay of content dye fluorescence intensity (see Fig. S2 in reference14). Typically, hundreds to thousands of time traces should be analyzed in order to obtain statistically significant histograms (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Examples of content and lipid mixing histograms (the fraction of vesicles that show a jump in fluorescence intensity (“occurrence”) in a particular time bin) vs. time. (a) Content mixing histogram, and (b) lipid mixing histogram with 200 msecs time binning. Inserts represent histograms from -2 sec. to 10 sec. Time point 0 corresponds to Ca2+ injection. The black lines are fitted exponential decay functions (f (t) = 0.03 + 30.3 e–4.4t + 2.0 e–0.5t and f (t) = 0.003 + 69.4 e–6.7t + 7.5 e–1.5t for the content and lipid mixing histograms, respectively). Insets are close-up views of the histograms around time point 0. The histograms are normalized with respect to the number of docked vesicles.

Some Ca2+-triggered fusion was observed with SNAREs and synaptotagmin 1 in the absence of complexin14. When complexin was added to the system during both the incubation and the observation periods, Ca2+-triggered fusion as well as docking were enhanced14. Immediate fusion was especially enhanced by complexin at lower (250 μM) Ca2+-concentration18. We are currently exploring the effects of other factors, such as Munc18 and Munc13, on our system.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Troubleshooting

| Step | Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | seal leak | It is critical that the glass surface is completely dry when establishing the seal. If a problem occurs, then discard the sample chamber and start over. It is recommended to apply pressure to each side of the sample chamber using a non-sharp object. |

| 19 and 58 | Too many fluorescent spots in bead sample | Make a new sample with lower concentration of beads. |

| 24 | Lipids are not dissolving | Occasional vortexing is necessary. Use low speed to avoid bubbles. |

| 63 | Bubbles in the tubing of the injection system | Push the syringe to remove any bubbles in the outlet tubing prior to attaching to the outlet. |

| 53 and 71 | Not enough or too many docked vesicles | Adjust the concentration of acceptor and donor vesicles. |

| 68 | Leaking occurs while drawing buffer | Adjust the position or pressure applied to the O-ring. |

| 70 | Severe photobleaching | Adjust ND filters in order to reduce power of lasers. |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37-MH63105 to ATB. We thank Daniel Cipriano, Rex Garland, and Mark Padolina for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Categories

Biochemistry; Neuroscience

Manuscripts where this method has been used:

Kyoung, M. et al. In vitro system capable of differentiating fast Ca2+-triggered content mixing from lipid exchange for mechanistic studies of neurotransmitter release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, E304-313, doi:10.1073/pnas.1107900108 (2011).

Author contributions M.K. designed the single vesicle content/lipid mixing system described in this Protocol, with input from S.C. and A.T.B.. Y.Z. developed the outlet port and programs for data analysis. J.D. made recent improvements to the vesicle content/lipid mixing system. M.K. and A.T.B. wrote the paper.

Competing financial interests The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katz B, Miledi R. Spontaneous and evoked activity of motor nerve endings in calcium Ringer. J Physiol. 1969;203(3):689–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudhof TC. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:509–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bean AJ, Zhang X, Hokfelt T. Peptide secretion: what do we know? FASEB J. 1994;8(9):630–638. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.9.8005390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voets T, Neher E, Moser T. Mechanisms underlying phasic and sustained secretion in chromaffin cells from mouse adrenal slices. Neuron. 1999;23(3):607–615. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindau M, Gomperts BD. Techniques and concepts in exocytosis: focus on mast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1071(4):429–471. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(91)90006-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sollner T, et al. SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature. 1993;362(6418):318–324. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1998;395(6700):347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson MB, Chapman ER. Fusion pores and fusion machines in Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Annual review of biophysics and biomolecular structure. 2006;35:135–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang J, et al. A complexin/synaptotagmin 1 switch controls fast synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cell. 2006;126(6):1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science. 2009;323(5913):474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1161748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma C, Li W, Xu Y, Rizo J. Munc13 mediates the transition from the closed syntaxin-Munc18 complex to the SNARE complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(5):542–549. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber T, et al. SNAREpins: Minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92(6):759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowen ME, Weninger K, Brunger AT, Chu S. Single molecule observation of liposome-bilayer fusion thermally induced by soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive-factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs). Biophysical journal. 2004;87(5):3569–3584. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyoung M, et al. In vitro system capable of differentiating fast Ca2+-triggered content mixing from lipid exchange for mechanistic studies of neurotransmitter release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(29):E304–313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107900108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Floyd DL, Ragains JR, Skehel JJ, Harrison SC, van Oijen AM. Single-particle kinetics of influenza virus membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(40):15382–15387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807771105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jun Y, Wickner W. Assays of vacuole fusion resolve the stages of docking, lipid mixing, and content mixing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(32):13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700970104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan YHM, van Lengerich B, Boxer SG. Effects of linker sequences on vesicle fusion mediated by lipid-anchored DNA oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(4):979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812356106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diao J, et al. Synaptic proteins promote calcium -triggered fast transition from point contact to full fusion. eLife. 2012 doi: 10.7554/eLife.00109. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cypionka A, et al. Discrimination between docking and fusion of liposomes reconstituted with neuronal SNARE-proteins using FCS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(44):18575–18580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906677106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon TY, Okumus B, Zhang F, Shin YK, Ha T. Multiple intermediates in SNARE-induced membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(52):19731–19736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606032103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karatekin E, et al. A fast, single-vesicle fusion assay mimics physiological SNARE requirements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(8):3517–3521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HK, et al. Dynamic Ca2+-dependent stimulation of vesicle fusion by membrane-anchored synaptotagmin 1. Science. 2010;328(5979):760–763. doi: 10.1126/science.1187722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karatekin E, Rothman JE. Fusion of single proteoliposomes with planar, cushioned bilayers in microfluidic flow cells. Nature Protocols. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang T, Smith EA, Chapman ER, Weisshaar JC. Lipid mixing and content release in single-vesicle, SNARE-driven fusion assay with 1-5 ms resolution. Biophysical journal. 2009;96(10):4122–4131. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diao J, et al. A single-vesicle content mixing assay for SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat Commun. 2010;1:54. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diao J, et al. A single vesicle-vesicle fusion assay for in vitro studies of SNAREs and accessory proteins. Nature Protocols. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature. 2000;406(6798):889–893. doi: 10.1038/35022702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun J, et al. A dual-Ca2+-sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature. 2007;450(7170):676–U674. doi: 10.1038/nature06308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vennekate W, et al. Cis- and trans-membrane interactions of synaptotagmin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(27):11037–11042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116326109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y, et al. Single Reconstituted Neuronal SNARE Complexes Zipper in Three Distinct Stages. Science. 2012 doi: 10.1126/science.1224492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weninger K, Bowen ME, Chu S, Brunger AT. Single-molecule studies of SNARE complex assembly reveal parallel and antiparallel configurations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):14800–14805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiessling V, Domanska MK, Tamm LK. Single SNARE-mediated vesicle fusion observed in vitro by polarized TIRFM. Biophysical journal. 2010;99(12):4047–4055. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghosh SK, et al. Measuring Ca2+-induced structural changes in lipid monolayers: implications for synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Biophysical journal. 2012;102(6):1394–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidelberger R, Heinemann C, Neher E, Matthews G. Calcium dependence of the rate of exocytosis in a synaptic terminal. Nature. 1994;371(6497):513–515. doi: 10.1038/371513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z, Liu H, Gu Y, Chapman ER. Reconstituted synaptotagmin I mediates vesicle docking, priming, and fusion. J Cell Biol. 2011;195(7):1159–1170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez JM, et al. Membrane fusion intermediates via directional and full assembly of the SNARE complex. Science. 2012;336(6088):1581–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.1221976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van den Bogaart G, et al. Membrane protein sequestering by ionic protein-lipid interactions. Nature. 2011;479(7374):552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takamori S, et al. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127(4):831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy R, Hohng S, Ha T. A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nature methods. 2008;5(6):507–516. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Sivasankar S, Nelson WJ, Chu S. Resolving cadherin interactions and binding cooperativity at the single-molecule level. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(1):109–114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811350106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pertsinidis A, Zhang Y, Chu S. Subnanometre single-molecule localization, registration and distance measurements. Nature. 2010;466(7306):647–651. doi: 10.1038/nature09163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bates M, Dempsey GT, Chen KH, Zhuang X. Multicolor super-resolution fluorescence imaging via multi-parameter fluorophore detection. Chemphyschem : a European journal of chemical physics and physical chemistry. 2012;13(1):99–107. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.