Abstract

North–South partnerships for health aim to link resources, expertise and local knowledge to create synergy. The literature on such partnerships presents an optimistic view of the promise of partnership on one hand, contrasted by pessimistic depictions of practice on the other. Case studies are called for to provide a more intricate understanding of partnership functioning, especially viewed from the Southern perspective. This case study examined the experience of the Tanzanian women's NGO, KIWAKKUKI, based on its long history of partnerships with Northern organizations, all addressing HIV/AIDS in the Kilimanjaro region. KIWAKKUKI has provided education and other services since its inception in 1990 and has grown to include a grassroots network of >6000 local members. Using the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning, the experience of KIWAKKUKI's partnership successes and failures was mapped. The findings demonstrate that even in effective partnerships, both positive and negative processes are evident. It was also observed that KIWAKKUKI's partnership breakdowns were not strictly negative, as they provided lessons which the organization took into account when entering subsequent partnerships. The study highlights the importance of acknowledging and reporting on both positive and negative processes to maximize learning in North–South partnerships.

Keywords: synergy, partnership, Africa, HIV/AIDS

INTRODUCTION

North–South partnership is a widely promoted approach for addressing the complex health challenges faced in the Global South. Governments, non-governmental organizations, private foundations and others are increasingly joining forces to provide local services and implement programmes in marginalized areas. In health promotion, such partnerships are ubiquitous. However, research examining their functioning is scant, and the knowledge base for guiding successful partnerships is shallow (Lister, 2000; Brehm, 2004a; Harris, 2008). One approach to building the necessary knowledge base is to examine and document the functioning of health promotion partnerships that are widely recognized as successes.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to use a systems model, the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning (BMCF), to map the successes and failures of one organization's North–South partnership experiences, and provide a robust analysis not typically captured in routine evaluations.

NORTH–SOUTH PARTNERSHIP FUNCTIONING

The empirical literature on Northern and Southern organizations is of limited utility. Specific partnerships as well as partnerships in general are compared with various conceptions of ideal partnerships, and are often found lacking (Brehm, 2004b). A handful of published case studies cite unequal power relations as a core problem. These studies report that unequal power can result in Northern dominance in agenda-setting, one-way accountability and taxing reporting requirements (Harrison, 2002; Mawdsley et al., 2002). In response to this power imbalance, Harris found Southern organizations sometimes resort to covert methods, e.g. fudging reports, to conform to Northern priorities (Harris, 2008).

Rather than strict Northern dominance, Ebrahim found in his case studies of two successful development organizations in India, that the relationships between these Southern NGOs and their funders were characterized by interdependence (Ebrahim, 2003). One of the areas this interdependence was evident is in the reporting practices of Southern NGOs as required by their Northern partners. Northern funders exchanged financial capital for symbolic capital (the reputation, status and authority provided by funding successful programmes). Ebrahim argues that it is this need to provide symbolic capital that drives overly quantitative and simplistic reporting requirements of Southern NGOs to funders—success must be easy to measure and free from the political and contextual complexities that more qualitative reporting might generate. Quantitative evaluations of projects and programmes also overlook higher-level processes that affect the operation of the NGO itself on a more general level. Reporting systems discourage the reporting of negative outcomes and encourage the exaggeration of positive outcomes, which leads to many missed opportunities for organizational learning (Ebrahim, 2003).

BERGEN MODEL OF COLLABORATIVE FUNCTIONING (BMCF)

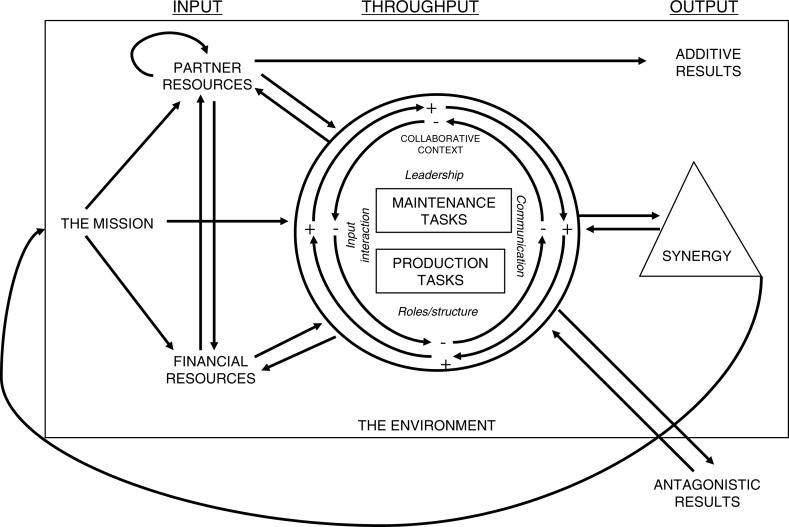

The framework for the analysis for the case study is the BMCF as depicted in Figure 1. The model is an extension of a model developed by Wandersman et al. (Wandersman et al., 1997). The extensions and modifications that comprise the Model as it is today were suggested by the empirical findings of several earlier studies. These include a global, professional health promotion partnership (Corbin, 2006), a national-level partnership for alcohol control (Endresen, 2007), a local partnership for enhanced patient nutrition in a large university teaching hospital (Corwin, 2009), an NGO–donor partnership in Kazakhstan (Dosbayeva, 2010) and a community-based health management information system project in Kenya (Kamau, 2010).

Fig. 1:

Bergen model of collaborative functioning.

The Model is a systems model with input, throughput, output and feedback components (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). The inputs to a partnership are its mission, partner resources and financial resources. Mission refers to the agreed-upon approach of the partnership to address a specific problem, issue or situation. Partner resources refer to the skills, knowledge, power, commitment, connections and other attributes that human resources contribute to the partnership. Financial resources encompass all monetary and material investments in the partnership.

The throughput section is the collaborative context. Inputs enter this context and interact positively or negatively as they work on the maintenance (administrative tasks) and production (relating to the collaborative mission) activities of the partnership. The collaborative context is shaped by the interaction of four elements: the inputs themselves as they engage in work, the leadership, roles and procedures and communication. These four elements can interact positively or negatively creating dynamic and reinforcing cycles within the collaborative context.

The outputs of the collaborative context may be synergy and/or its opposite, antagony, in which the costs of partnership are perceived to outweigh the benefits (Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008).

The term ‘synergy’ is often employed to describe the multiplicative interaction of people and resources to solve problems that cannot be tackled by any of the partners working alone, described mathematically as 2 + 2 = 5 (Lasker et al., 2001; Brinkerhoff, 2002; Ball et al., 2003; Corbin and Mittelmark, 2008). In the Model, an arrow from synergy feeds back into the collaborative context indicating the positive impact success (achieving synergy) can have on functioning and input recruitment.

Antagony is not the mere failure to produce synergy, it is the wasting of partner and financial resources to the extent that more is consumed in the process of collaborating than is produced, 2 + 2 = 3, or even 2 + 2 = 0. Arrows depict antagony feeding back into the collaborative context and to the inputs indicating the negative impact antagony can have on functioning and resource acquisition.

THE CASE

In 1990, a small group of Tanzanian and expatriate women in Moshi, Kilimanjaro worked together to plan several public education campaigns for World AIDS Day (Setel and Mtweve, 1995; Haffagee, 2003). This led to the founding of KIWAKKUKI (Kikundi cha Wanawake Kilimanjaro Kupambana na UKIMWI) or Women Against AIDS in Kilimanjaro, which began work by providing information and education to prevent the spread of HIV and reduce stigma. Gradually, their work expanded into voluntary counselling and testing, support for adults and children living with HIV/AIDS, and advocacy and policy development. Unpaid volunteers carry out most of KIWAKKUKI's activities (Itemba, 2007). By 2007, KIWAKKUKI had grown to over 6000 members in 160 grassroots groups across the Kilimanjaro region (Itemba, 2007).

Over the years, many organizations from the North have chosen to partner with KIWAKKUKI. These organizations have included universities (University of Bergen, Duke University), private philanthropic foundations (Bernard van Leer, Ebert, Glaxo Wellcome, Terre des Hommes Netherlands and Switzerland, Child Foundation Netherlands), national development agencies (Germany, Norway, Netherlands, Ireland, USA), international non-governmental organizations (e.g. FamFaith), non-governmental organizations (The Women's Front of Norway, Oxfam Ireland, Positive Steps Scotland) and services clubs (e.g. Rotary Norway). Some of these partnerships have endured many incarnations and renewals over years. Others have consisted of a single programme carried out over many years. Less often, a partnership has been a one-off programme without renewal. Northern donors account for 90% of KIWAKKUKI's funding, with membership fees and income-generating activities providing the remaining 10% (Itemba, 2009). KIWAKKUKI is recognized both within Tanzania and internationally as being well-established and effective (Lie and Lothe, 2002; Haffagee, 2003; Strauch and Eickhoff, 2004; Thielman et al., 2006).

METHODS

Data were obtained from KIWAKKUKI working documents (e.g. email), archival records (e.g. proposals, budgets, reports), direct observation and through interviews with nine individuals. The data obtained through documents, records and observations provided background to inform the analysis but the results presented here are based on themes emerging from the interviews.

Of the nine interview participants, eight were currently employed by KIWAKKUKI at the time of the interview and one was a voluntary member with a long history of working with KIWAKKUKI. The participants ranged in age from their early 20s to over 60, they were all women and either currently live in, or formerly lived in, the Kilimanjaro region. These nine individuals were selected for their extensive professional interactions with Northern partners in the course of their work. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by the first author, with the third author present and asking an occasional follow-up questions. Participants were asked open-ended questions, in a semi-structured format, about their interactions with Northern organizations. The interviews began with a brief introduction to the study, the kinds of information of interest and then the researchers just allowed the participants to recount stories of their experiences asking for clarification or more detail as needed. This is an example of the typical introduction presented by the interviewer: ‘In terms of the partnership project, what I am interested in is your individual experience when partners from the North are involved in projects, provide money or provide expertise, or whatever the partnership arrangement is. When it works well, how does it function? What is communication like? What roles do different people play? Who are the leaders of the partnership? How does the work get done?’ The content of the questions asked varied considerably from interview to interview depending upon the person's role in the organization. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed by the first author.

The analysis of data for this study followed the steps recommended by Creswell (Creswell, 2007). The first stage of analysis began as discussion, reflection and the identification of themes directly after interviews through dialogue between the first and second author. Subsequently, all texts were read thoroughly by the first author, themes were noted and compared with the initially identified themes, coded and condensed to fewer and fewer codes (noting outliers); then analysed on their own and also in relation to the BMCF.

RESULTS

The results are presented according to the BMCF, the themes that emerged from the interviews and are relevant to this paper are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Themes emerging from interviews with KIWAKKUKI Staff/members

| Themes emerging from interviews | Nine participants |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 1. Grassroot volunteers contribute financially to NSP programmes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 2. KIWAKKUKI staff contribute financially to NSP programmes | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 3. Northern partners provide ‘partner resources’, such as capacity building | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 4. Mission guides decision-making for both Northern partners and KIWAKKUKI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 5. KIWAKKUKI exerts influence in its NSPs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 6. Inadequate resources are provided for maintenance tasks (such as, reporting) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7. Provided a concrete example of synergy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 8. Provided a concrete example of anatagony | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

Check mark indicates that the participant addressed the theme during their interview.

Input

KIWAKKUKI is well resourced, but the various contributions are unevenly made. On paper, financial resources come predominantly from the North, professional expertise comes from both North and South, and an overwhelming proportion of labour comes from the South. However, the day-to-day experience of KIWAKKUKI, especially in regard to financial contribution runs counter to the caricature of northern partners contributing only money and demands.

While balance sheets show that 90% of funding for programmes comes from the Northern partners, financial contributions are also made locally by community volunteers and staff. Employees routinely work unpaid extra hours to meet reporting deadlines and provide charity from their own pocket to KIWAKKUKI's clients. It is customary to bring gifts when visiting the sick in Tanzania, so individual volunteers often give materially as well giving their time, as one participant describes:

We have been discussing for a long time that apart from donor contributions, our grassroots groups are really, really contributing a lot because we cannot actually value the materials they bring and how often and how many patients do they give those materials (to) from their own money, from their own family.

Because it is so difficult to quantify these inputs, and also because the value of ‘a dollar’ differs so drastically between North and South, the depiction of ‘90 percent of funding coming from North versus ten percent contributed locally’ does not adequately reflect the local stake and thus sense community of ownership.

Also bucking the stereotype, some of KIWAKKUKI's Northern partners contribute expertise to their partnerships in addition to their financial support. This expertise often comes in the form of:

Capacity building for the partnership's maintenance tasks (training on report and proposal writing);

We had a capacity building on report writing. The other time we had capacity building on financial reporting.

Professional exposure and links to connect KIWAKKUKI with other funding organizations;

We were called to (Northern Country) to present our work … We gave different presentations to different (institutions), you know? And also they support us because they link us to other donors.

Ideas and guidance on planning production activities:

For the most donors—basically all of them—their role is to provide funding to us and also they provide support—support for—you know they would like to ask us, ‘OK, how is the project going?’ If they can give their views ‘Why don't you do this.’—in case there is any problem and we share with them—they help us.

Logistical support given by some Northern partners when they have had difficulty meeting report deadlines.

They can give a good format, so it will be easy for you to fill. To fill in that, yes, for this activity, I have done this and this was the outcome, this was the result, this was the impact. So by having this simple format—you can see they are also supporting.

KIWAKKUKI also provides evidence that money is not the driving force behind synergy, but is an enabling force. The vast amount of voluntary labour that keeps KIWAKKUKI at work could never be compensated by Northern donations. Voluntary labour, too, is not a driving force, but an enabling force, since the labour is essential, but not sufficient, for KIWAKKUKI to meet its mission. All contributions are seen as essential.

We really need donors to help us and we really need the grassroots women's groups to do the work.

The input ‘mission’ can be a powerful motivating factor for partners—attracting donors who wish to support particular activities. For instance, the partnership with Bernard van Leer Foundation has a mission aligned with its organizational mandate—to provide holistic care to orphans and vulnerable children aged 0–8 (Bernard van Leer Foundation, 2009). Alignment with mission is also a key motivating factor for the selection of partners by KIWAKKUKI. Their board is very strict in adhering to their 5-year strategic plan when considering whether or not to accept offers of partnership and will only agree to engage in programmes and projects that are in line with KIWAKKUKI's long-term plan.

KIWAKKUKI's values of voluntarism and community empowerment are central to their mission; they believe this is crucial to their success with Northern partners:

Because we are trying to live our values … people come, they see the values at work. So they say ‘this is the organization we should be working with.’ The warmth, the commitment, the results, the grassroots nature. You know? Because they say ‘there are many organizations which claim to work with grassroots but when you visit them, you don't see much about working with the grassroots. Their work is concentrated in urban areas.’ But when they come, we show them where we are and that is where our work is visible. And they see we are really working with the communities, with marginalized communities, rather than working with urban communities.

Unfortunately, funding priorities for Northern partners change over time and according to political whims. There might be substantial support for one type of mission at a given time but less for others. One participant mentioned a current example:

I think most of donors are interested in supporting the orphans but for PLHAs (people living with HIV/AIDS), nobody is interested.

Throughput

The inputs of the partnership (partner resources, financial resources and the mission) interact as the partnership engages in maintenance and production activities. It is within this interaction that the power of each partner is manifest and exchanged. The positive experiences of KIWAKKUKI that resulted in synergy were defined, according to the study participants, by an exchange of power and interdependence. Participants described dynamic power relations depending upon the activity. KIWAKKUKI's Board has the power to accept or reject partners and activities in accordance with its strategic plan. KIWAKKUKI is always involved in the drafting of proposals and involves its grassroots members in this process as well. They largely decide what to do and who shall receive the services (Production).

Northern partners, on the other hand, control funding and are therefore in a position to demand a degree of communication, accounting and reporting to track the use of those funds (Maintenance). Rather than resenting this, the participants interviewed for this study felt comfortable with this interdependency. One participant explains:

Our donors actually fund us from what we ask to do. They don't come and impose things on us. But when it comes to the accountability, they need (reports). They have given you money, they want to see what you have done. That is when they have power on that but within the activities that we are doing, they don't impose anything. They are not pushing us ‘do this, do that.

When this balance is achieved, the positive processes of the partnership dominate the collaborative context. Negative interactions still take place but are dwarfed by the predominantly positive exchange.

Output

As described in the ‘Case’ section, KIWAKKUKI's ability to produce synergy through its North –South partnerships is the basis of its documented success as an organization.

Many Northern organizations are interested in providing school fees and materials for orphaned and vulnerable children. However, the simple distribution of such money and materials does not always result in a positive impact in the recipient community (see Daniel, 2008). KIWAKKUKI's partnerships, on the other hand, combine this Northern funding with formal grassroots consensus-building processes where community members meet and debate the relative status and needs of recipient children, so when funds are distributed there is local support for those recipients rather than resentment or hostility. Through such decision-making processes, local communities are empowered. Northern organizations are able to provide financial help to those in most critical need as defined by local standards, information Northern NGOs could never have access to from their offices in Europe or the USA. It is this interaction—more than the sum of the individual contributions—that characterizes partnership synergy. Similar processes can be found in their education programmes, home-based care and other partnership initiatives.

Additionally, in KIWAKKUKI's experience, synergy has also yielded unexpected benefits. An example of this occurred when the work of one of KIWAKKUKI's partnerships was later disseminated by another Northern partner for use in their other partnerships throughout Tanzania:

(Northern Donor) read about (the work of another partnership), they said, ‘This is good.’ And now they want it to be adopted into their (KIWAKKUKI) program, into their funding—but also into other partners which they fund.

These positive experiences feed back into the functioning of the partnership and help to recruit more inputs in the form of additional partners and funds. KIWAKKUKI's success in working in its partnerships attracts new donors. Their reputation for engaging in successful partnerships is such that in recent years, they rarely have had to seek out Northern organizations for funding. One interviewee described how Northern donors now approach them:

I don't remember when I last wrote a proposal just anonymously.

ANTAGONY

The construct ‘antagony’ is a core contribution of the BMCF to health partnership scholarship. Antagony can have its root in any number of processes within the partnership. For example, in one instance KIWAKKUKI experienced a negative partnership interaction with a Northern donor that, for reasons unknown to KIWAKKUKI, was marked by distrust. One participant described the circumstance:

We have (Northern donor) – they are so skeptical, they keep coming in with doubts about what we are telling them and all this … (questions) we don't get with other donors. We can say, ‘OK, we (did the thing they asked) on such and such date.’ They say, ‘We must have (verification).’ ‘OK’. We send them (our word of what we did). ‘We must get (external confirmation).’ Even though we have told them. They still want to confirm (externally). We don't get those things from other donors.

The distrust of the Northern partner led them to demand more communication, accounting and reporting. This increased the draw upon KIWAKKUKI resources to fulfil the greater demand for these maintenance tasks and drained resources away from the purposes of engaging in production tasks (those related directly to the mission).

A second example also involves the interaction of partner resources. Capacity building is often a component of KIWAKKUKI's partnership arrangements. However, at one time, one of their Northern partners thrust ‘capacity building’ on KIWAKKUKI in a way that they had not agreed to. KIWAKKUKI was forced to rewrite several versions of each proposal that was sent, each draft was returned to KIWAKKUKI with more and more edits required. One participant described that a proposal would have to be written 10 times before finally being approved. KIWAKKUKI found this experience to not only consume precious resources, but also to be degrading. Another participant described it:

At the end of the day, we feel like babies, babies, babies.

A final example involves reporting activities. Throughout the interviews with KIWAKKUKI staff and evidenced by the volume of quarterly and annual reports given to the researchers to analyse for this case study, reporting to Northern donors is by far the most significant maintenance task undertaken by KIWAKKUKI staff and volunteers. Numerous challenges with reporting were described by participants of the study. Reporting begins within KIWAKKUKI at the grassroots level. Each district must capture and convey data to programme officers so reports can be complied on a monthly, quarterly and annual basis. Delays are common in receiving this data caused by poor transportation and communication to and from remote villages. Conforming reports to the many diverse formats required by each donor is also time consuming and often redundant. Donors differ not only in report formatting requirements, but also in the timing of their fiscal years, which further complicates reporting routines. Some donors have specific software systems into which they require that report data be entered.

Taken together, the various reporting requirements are a tremendous drain on Southern partner resources. To compound these challenges, very few donors actually provide financial resources for the administrative activities demanded in their contracts. In theory the antagony resulting from the diversion of resources from production to maintenance tasks is preventable—if, for instance, reporting processes could be streamlined among Northern partners. Unfortunately, these diverse reporting requirements are often out of the control of the Northern partners as well as they are imposed by the Northern partners’ funders.

As illustrated above, antagony can feed back into the partnership, causing problems in functioning. However, the case of KIWAKKUKI demonstrates that antagony can also foster positive outcomes. The second example described above, KIWAKKUKI's experience of feeling like ‘babies’, actually motivated the leadership to confront the Northern partner. KIWAKKUKI refused to conform to their demands and suggested the Northern funder withdraw their funding if the proposal was not acceptable in its current form. This confrontation lead to some healthy discussion and KIWAKKUKI and that Northern organization went on to enjoy a fruitful and productive partnership for many years.

DISCUSSION

The BMCF was employed in this study as a framework to identify and examine the functioning of KIWAKKUKI's partnerships.

The examination of inputs revealed that Northern ‘financial partners’ often also contribute human resources and that Southern ‘partner resources’ often contribute substantial (in relative terms) monetary and material resources.

In terms of partnership functioning, the findings here describe an exchange of power between Northern and Southern partners. There is no indication that power relations are perceived as equal—at times KIWAKKUKI has the power (e.g. saying ‘no’ to funding) and at other times Northern partners have the power (e.g. demanding reports). Lister suggests that unequal power relations might preclude Northern and Southern organizations from claiming ‘partnership’ (Lister, 2000). The findings here do not support such a notion. Rather, a sharing of power between partners was accepted as part of the partnership interaction.

There is evidence in the data of considerable partnership synergy, and for some antagony. Distrust had a negative impact on partnership functioning in some instances, as it drew resources from production tasks to accommodate the increased maintenance burden. This study documents the administrative burden of reporting, also observed in many other studies (e.g. Ashman, 2001; Mawdsley et al., 2002; Harris, 2008). Northern organizations could do much to alleviate this burden by providing funding to employ people (and supplies) to produce the reports they require. They could also be flexible in terms of their formats, or perhaps Northern partners could join together and standardize some of these procedures.

This study used the BMCF to describe KIWAKKUKI's partnerships. This is the first instance of the use of the BMCF to study North–South partnerships. It is the judgement of the authors that the BMCF served its function well, and that its systems perspective on partnership functioning seems equally applicable to North–South partnerships as to the other forms of partnership studies previously undertaken with the BMCF. The Model may therefore prove a useful tool for the future evaluation of North–South partnerships by us and by others. Perhaps its greatest utility is that it provides for the consideration not only positive, but also of negative partnership processes, simultaneously.

One limitation is noteworthy. It is questionable if Northern researchers have sufficient ability to ascertain the perspectives of Southern partners given both their remoteness from the context and their ability or inability to develop the confidence of participants (Ryen, 2003). The third author, who was involved in both data collection as well as analysis, speaks the local language and has spent 23 years living in the region or keeping in continual contact with KIWAKKUKI—her expertise and understanding has been relied upon to help counter this limitation.

CONCLUSION

Ebrahim urges both Northern and Southern organizations to move away from the limits of a strictly quantitative reporting mechanism that encourage the communication of success while keeping the analysis of challenges within partnerships superficial. The BMCF is a tool that might facilitate a shift to a more nuanced analysis (Ebrahim, 2003).

The BMCF offers a consistent frame that enables detailed analysis of partnership across many facets of partnership functioning. Thus, this ‘mapping’ of successful North–South partnerships illuminates some key features that may explain KIWAKKUKI's ability to produce synergy, when so many other North–South partnerships fail. First, the enormous contribution of a voluntary labour of 6000 grassroots members and the personal financial contributions contributed by most were perceived by those interviewed at KIWAKKUKI to be more balanced than is typically depicted in evaluations that may not examine ‘partner contributions’ in the robust way dictated by the BMCF. Second, the clear role of ‘mission’ in the BMCF enabled the examination of KIWAKKUKI's day-to-day interaction with their mission (via their strategic plan) that was a key to selecting Northern partners and producing synergy within those partnerships. Other frameworks of evaluation may or may not have picked up on this crucial point of interaction and criteria for decision-making.

The ‘mapping’ of antagony also produced results that offer insights into how to further improve North–South partnership, such as the example of KIWAKKUKI straying away from their ‘mission’ and experiencing less than optimal results. Further research using the BMCF to examine North–South partnerships that do not have the history of success of KIWAKKUKI and its partners could yield other findings that could contribute to improving these relationships.

By considering antagony and negative processes along side positive processes and synergy, the BMCF acknowledges and normalizes the existence of both in every partnership interaction. It becomes a question not of ‘do negative processes exist?’ but rather ‘are negative processes overshadowing partnership efforts in a way that is impeding synergy?’ This could open up dialogue and reflection on issues that are seldom in focus in traditional evaluation methodologies.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the University of Bergen, Norway.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the women of KIWAKKUKI for their time, hospitality and candour. Thanks also to Jennifer and Derick Brinkerhoff for their insightful feedback on an early draft and to the anonymous reviewers who improved the utility of the paper enormously.

REFERENCES

- Ashman D. Strengthening North-South partnerships for sustainable development. NonProfit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2001;30:74–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M., Le Ny L., Maginn P. Synergy in urban regeneration partnerships: property agents’ perspectives. Urban Studies. 2003;40:2239–2253. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard van Leer Foundation. 2009. Website page http://www.bernardvanleer.org/partners/africa/tanzania_-_kiwakkuki. (last accessed 20 August 2009)

- Brehm V. Introduction: fostering autonomy or creating dependence? In: Brehm V., editor. Autonomy or Dependence? Case Studies of North-South NGO Partnerships. London: INTRAC; 2004a. pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm V. Partnership as a contested concept. In: Brehm V., editor. Autonomy or Dependence? Case Studies of North-South NGO Partnerships. London: INTRAC; 2004b. pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff J. M. Partnership: promise and practice. In: Brinkerhoff J. M., editor. Partnership for International Development: Rhetoric or Results? London: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2002. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H. Interactive Processes in Global Partnership: A Case Study of the Global Programme for Health Promotion Effectiveness. Paris: International Union for Health Promotion and Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H., Mittelmark M. B. Partnership lessons from the global programme of health promotion effectiveness: a case study. Health Promotion International. 2008;23:365–371. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin L. University of Bergen; 2009. Factors and Processes that Facilitate Collaboration In a Complex Organisation: A Hospital Case Study. http://hdl.handle.net/1956/4453 . [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. London: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M. L. The Hidden Injuries of Aid: Unintended Side Effects of Humanitarian Support to Vulnerable Children in Makete, Tanzania. Paper presented at Child and Youth Research in the 21st Century: A Critical Appraisal. First international conference organized by the International Childhood and Youth Research Network; 28–29 May 2008; Cyprus. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dosbayeva K. University of Bergen; 2010. Donor-NGO collaboration functioning: case study of Kazakhstani NGO. https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4450 . [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim A. NGOs and Organizational Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Endresen E. University of Bergen; 2007. A Case Study of NGO Collaboration in Norwegian Alcohol Policy Arena. https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4466 . [Google Scholar]

- Haffagee R. The Women of KIWAKKUKI: Leaders in the Fight Against HIV/AIDS in Kilimanjaro. Tanzania: Duke University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harris V. Mediators or partners? Practioner perspectives on partnership. Development in Practice. 2008;18:701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison E. ‘The problem with the locals’: partnership and participation in Ethiopia. Development and Change. 2002;33:587–610. [Google Scholar]

- Itemba D. The contribution of grassroots groups in HIV/AIDS prevention and care in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania: the case of KIWAKKUKI. In: Lothe M., Daniel E. A., Snipstad M. B., Sveaass N., editors. Strength in Broken Places. Bergen: University of Bergen; 2007. pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Itemba D. HIV/AIDS Community Response by Kilimanjaro Women's Group Against AIDS– KIWAKKUKI. Presentation given on 23 March 2009 at the University of Bergen; Norway. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamau A. Documentation of the Implementation strategy. A case study for the Kibwezi Community-Based Health Management Information System project; Kenya. University of Bergen; 2010. https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4276 . [Google Scholar]

- Lasker R., Weiss E. S., Miller R. Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Millbank Quarterly. 2001;79:179–205. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie G. T., Lothe E. A. KIWAKKUKI: Women against AIDS in Kilimanjaro Region—A Qualitative Evaluation. Bergen: Women's Front of Norway; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lister S. Power in partnership? An analysis of an NGO's relationships with its partners. Journal of International Development. 2000;12:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mawdsley E., Townsend J. G., Porter G., Oakley P. Knowledge, Power and Development Agendas: NGOs North and South. Oxford: INTRAC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ryen A. Cross-cultural interviewing. In: Holstein J. A., Gubrium J. F., editors. Inside Interviewing: New Lenses, New Concerns. London: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Setel P., Mtweve S. The Kilimanjaro women's group against AIDS. In: Klepp K.-I., Biswalo P. M., Talle A., editors. Young People at Risk: Fighting AIDS in Northern Tanzania. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Strauch I., Eickhoff A. B. KIWAKKUKI—women fight against HIV/AIDS, an encouraging example for social work in Tanzania. Social Work and Society. 2004;2:237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Thielman N. M., Chu H. Y., Ostermann J., Itemba D. K., Mgonja A., Mtweve S., et al. Cost-effectiveness of free HIV voluntary counselling and testing through a community-based AIDS service organization in Northern Tanzania. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:114–119. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A., Goodman R. M., Butterfoss F. Understanding coalitions and how they operate: an ‘open systems’ organizational framework. In: Minkler M., editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1997. pp. 261–277. [Google Scholar]