Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Gastric neuromodulation (GNM) has been advocated for the treatment of drug refractory gastroparesis or persistent nausea and vomiting in the absence of a mechanical bowel obstruction. There is, however, little in the way of objective data to support its use, particularly with regards to its effects on gastric emptying.

METHODS

Six patients (male-to-female ratio: 4:2, mean age: 49 years, range: 44–57 years) underwent the GNM between April and August 2010. Three patients had confirmed slow gastrointestinal transit. Aetiology included previous gastric surgery in two, diabetes in one and idiopathic nausea and vomiting in three patients. GNM pacing wires were placed endoscopically and left in situ for seven days. Pa-tients underwent gastric scintigraphy before and 24 hours after the commencement of GNM. Total gastroparesis symptom scores (TSS), weekly vomiting frequency scores (VFS), health-related quality of life (using the SF-12® questionnaire), gastric emptying, nutri-tional status and weight were compared before and after GNM.

RESULTS

TSS improved after GNM in comparison with baseline data. VFS improved in three of four symptomatic patients. The SF-12® physical composite score improved in four patients (27.5 vs 34.3) and the mental composite score improved in five patients (34.9 vs 35.9). All patients reported an improvement in oral intake. A significant weight gain (mean: 1kg, range: 0.3–2.4kg) was observed over seven days. Gastric emptying half-time improved in four patients.

CONCLUSIONS

GNM improved upper gastrointestinal symptoms, quality of life and nutritional status in patients with intractable nausea and vomiting. GNM merits further investigation.

Keywords: Gastroparesis, Gastric motility, Gastric neuromodulation, Gastric scintigraphy

Gastroparesis is a common and challenging medical problem. The symptoms are non-specific and include nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, early satiety and abdominal pain.1,2 The symptoms can mimic gastric ulcers, gastric outlet obstruction, biliopancreatic disorders, gastric cancers and bowel pathologies.3 For this reason, the diagnosis is made after the exclusion of organic gastrointestinal (GI) pathologies and confirmed with objective evidence of delayed gastric emptying (GE).4 Gastroparesis can be idiopathic or secondary to conditions such as diabetes, previous gastric surgery and vagotomy.

The treatment of gastroparesis includes the treatment of the underlying cause, dietary modification, and prokinetic and antiemetic drugs. Results are very variable. In the last decade, gastric neuromodulation (GNM) has emerged as a new treatment option for severe and drug refractory gastroparesis. There are many reports of its use but few objective data on its effects on GE. Furthermore, the exact mechanism by which GNM may improve the symptoms of gastroparesis remains unclear.

This paper presents our experience of six patients with temporary GNM who underwent careful pre and post-operative objective assessment of GE. In addition, we recorded symptom improvement, nutritional outcomes and quality of life in each patient.

Methods

Patient selection and assessment

Patients with refractory nausea and/or vomiting who failed to respond to medical treatment and were not found to have any correctable pathology were selected for consideration of GNM (Table 1). At least one of the two symptoms had to be severe and associated with nutritional or quality of life (QOL) impairment to be included for the procedure. The patients were investigated to exclude mechanical gastric outlet and bowel obstruction by endoscopy and radiological investigations including plain abdominal radiography, computed tomography and/or contrast studies.

Table 1.

Demographic data and underlying pathology

| Patient | Sex | Age | Duration of symptoms | Aetiology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 57 | 12 years | Annular pancreas treated with subtotal gastrectomy, RYGB, refashioning of RYGB |

| 2 | M | 40 | 6 years | Slow panenteric gastrointestinal transit treated with ileostomy. Recurrence of symptoms. |

| 3 | M | 44 | 3 years | Idiopathic nausea and vomiting, weight loss 15kg |

| 4 | F | 57 | 3 years | Longstanding diabetes mellitus (for 15 years) |

| 5 | F | 54 | 3 years | Idiopathic severe nausea, bloating and abdominal pain |

| 6 | M | 44 | 4 years | Longstanding nausea, acid reflux and bloating. Treated with Nissen fundoplication. Symptoms deteriorated necessitating the reversal of Nissen fundoplication. |

RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

All patients had an initial trial of antiemetic and/or prokinetic drugs for at least six months. After a failure with medical treatment, they were considered for a trial of temporary GNM. Baseline data such as the total symptom score (TSS), the weekly vomiting frequency score (VFS), QOL, using the 12-item short form health survey (SF-12®), and nutritional status were assessed in the selected patients. TSS is the sum of scores from five four-point categorical scales (0 = symptoms absent; 4 = symptoms extremely frequent and extremely severe) for the symptoms of vomiting, nausea, early satiety, bloating and abdominal pain. In addition, all the patients underwent a standard gastric scintigraphy before GNM.

Procedure

GNM (Enterra® therapy, Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN, US) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. As this procedure is not a routine practice in our institution, clinical service approval was obtained.

All the patients underwent GNM in the endoscopy department at Hull Royal Infirmary, East Yorkshire, between April and August 2010. Under local anaesthesia (lidocaine 10% throat spray) and sedation, a gastroscopy was performed with a double lumen endoscope. A suitable area, about 10cm proximal from the pylorus on the greater curvature of stomach, was identified. A gastric pacing wire was implanted in the submucosal area with gentle clockwise rotation. The wire was secured by application of two clips on the wire using the second lumen of the endoscope.

The implanted pulse generator (IPG) was programmed with commonly used high frequency GNM parameters (frequency 0.2Hz, intensity 5mA, pulse duration 0.33ms, cycle ON 0.1s, cycle OFF 5.0s) using an external programmer (model 4351, Medtronic Inc). Those parameters were used throughout the duration of the test period. The pacing wire was then brought out of the nostril and attached to the IPG. The parameters on the IPG were reconfirmed and the wire was left in situ for seven days. The procedure was tolerated well by all the patients and no peri or post-procedure complications were recorded.

Patients

Six patients (4 male) were selected for the GNM. The mean age was 49 years (range: 44–57 years). Patient characteristics and demographic data are summarised in Table 1. The average duration of their symptoms was five years. Four of the six patients required multiple hospital admissions due to dehydration, electrolyte disturbances and nutritional deficiencies. One required enteral and parenteral supplementary nutritional support. Three patients had confirmed slow GE assessed by gastric scintigraphy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Alterations in clinical symptoms and gastric emptying following gastric neuromodulation

| Patient | TSS | VFS | Weight gain | GE half-time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative | Post-operative | Pre-operative | Post-operative | Pre-operative | Post-operative | ||

| 1 | 17 | 13 | 30 | 0* | 1.0kg | 515 | 600 |

| 2 | 16 | 0 | 20 | 0* | 2.4kg | 104 | 42 |

| 3 | 13 | 3 | 20 | 3* | 1.0kg | 29 | 23 |

| 4 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0.3kg | 98 | 41 |

| 5 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.9kg | 37 | 71 |

| 6 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.5kg | 65 | 48 |

| Median | 13.5 | 3.5 | 11.5 | 0 | 1.02kg (mean) | – | – |

| IQR | 12.5–16.25 | 2.25–7.75 | 0–22.5 | 0–3 | – | – | |

| p-value | 0.02 | 0.10 | – | – | |||

TSS = total symptom score; VFS = weekly vomiting frequency score; GE = gastric emptying; IQR = interquartile range

Scintigraphy

Scintigraphy was used as a gold standard for measurement of GE before and after GNM. After an overnight fast, subjects were given a test meal containing small dose 99mTc (0.3mSv). The meal was prepared just before the beginning of the test and consumed within 10 minutes. With the subjects lying supine, dynamic acquisitions were taken for 100 minutes and each image comprised anterior and posterior acquisitions. The regions of interest were drawn on anterior and posterior images. Geometric means of radioactivity were calculated and computer generated time activity curves generated. The GE half-time was calculated and compared with our reference values (99 ±26 minutes) based on a study in healthy volunteers.5

Follow-up

After the application of GNM, the patients were admitted to the ward for observation for 24 hours. A repeat gastric scintigraphy was performed on the first day after GNM. Patients were then sent home and requested to keep a diary of symptoms, medication and food intake for the next seven days. The patients were reviewed in the outpatient department for the removal of the wires seven days after the procedure. The results of repeat QOL, weight and nutritional assessments were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Pre and post-GNM data including TSS, VFS, QOL and GE half-time were entered into an Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, US) spreadsheet. Comparison between pre- and post-GNM was performed using SPSS® version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, US). The Wilcoxon test was used to determine the differences between medians.

Results

The GNM procedure was performed in all six patients without any complications. All patients tolerated the wire for a week with no spontaneous dislodgement of the wire. Alterations in GE, clinical symptoms and QOL following GNM are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Alterations in SF-12® quality of life scores following gastric neuromodulation

| Patient | SF-12® PCS | SF-12® MCS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative | Post-operative | Pre-operative | Post-operative | |

| 1 | 22.8 | 21.7 | 39.1 | 42.6 |

| 2 | 38.8 | 52.4 | 52.5 | 62.1 |

| 3 | 27.2 | 40.5 | 36.7 | 45.2 |

| 4 | 27.9 | 28.1 | 24.3 | 29.2 |

| 5 | 23.4 | 21.1 | 17.1 | 22.8 |

| 6 | 32.3 | 53.9 | 33 | 18.2 |

| Median | 27.5 | 34.3 | 34.9 | 35.9 |

| IQR | 23.3–33.9 | 21.6–52.8 | 22.5–42.5 | 21.6–49.4 |

| p-value | 0.24 | 0.34 | ||

PCS = physical composite score; MCS = mental composite score; IQR = interquartile range

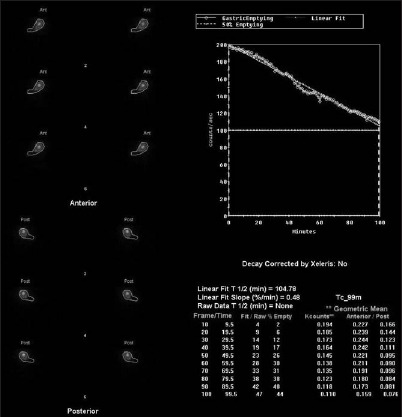

Gastric emptying

GE half-time improved in four patients (see Figs 1 and 2 as examples) and increased in one patient (Table 2). One patient with a previous history of a gastrectomy and a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass had a very prolonged GE time but there was no evidence of obstruction on endoscopic or radiological investigations. GNM did not have any effect on GE in this patient (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Delayed gastric emptying of a patient with gastroparesis before gastric neuromodulation (gastric emptying half-time: 104 minutes)

Figure 2.

Improved gastric emptying of a patient with gastroparesis before gastric neuromodulation (gastric emptying half-time: 42 minutes)

Clinical symptoms and nutritional status

Results are expressed as median (inter quartile range). Overall TSS improved after GNM in comparison with the baseline data (13.5 [12.5–16.25] vs 3.5 [2.25–7.75]). VFS improved in three of the four symptomatic patients. All patients reported an improvement in oral intake and a mean weight gain of 1.02kg (range: 0.3–2.4kg) was observed over the seven-day test period (Table 2).

Quality of life

Health-related QOL was assessed using the SF-12® questionnaire. The physical composite score improved in four patients (27.5 [23.3–33.9] vs 34.3 [21.6–52.8]) and the mental composite score improved in five patients (34.9 [22.5–42.5] vs 35.9 [21.6–49.4]) (Table 3).

Discussion

This small experience with temporary GNM demonstrates that GNM is safe and effective in improving both the clinical symptoms of gastroparesis and the objective measurements of GE.

Multiple case series have been published in support of the efficacy of GNM in gastroparesis and intractable nauseas and vomiting.6–16 The bulk of the treated patients consisted of diabetics and idiopathic gastroparesis followed by patients with post-surgical and post-transplant gastroparesis. In 2009 a systematic review of case series elaborated on the outcome of the procedure in different centres across the world.17 The review demonstrated the significant benefits for high frequency GNM in the treatment of refractory gastroparesis. Reduction in nausea and vomiting, nutritional support and an improvement in GE were also emphasised.

In addition to diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis, studies have demonstrated promising results in post-gastric surgery gastroparesis refractory to medical treatment with GNM.11,18 There are, however, only a few studies focusing on the objective changes in GE following GNM.9–11,17 The data are inconclusive in terms of the effect of GNM on GE. In one study, GNM in 16 post-surgical patients improved GI symptoms but did not change GE after 12 months.11 In another study, both liquid GE (after temporary GNM) and solid GE (after permanent GNM) improved in patients with gastroparesis secondary to diabetes, post-surgical and idiopathic cases.19 Others have also reported improvement of GE after six months and one year.9

Temporary GNM electrodes can be placed using an endoscopic approach whereby the electrode (wire) is brought out of the nose. Another method involves the transperitoneal intramuscular (muscularis propria) placement using a percutaneous endoscopic or laparoscopic technique.19 The wire is then attached to the IPG and programmed to deliver low energy, high frequency GNM as described above. Endoscopic placement of temporary GNM has become a more widely established method although both endoscopic and percutaneous methods for placement of temporary wires are safe and effective.19 If successful, temporary GNM is replaced by a permanent device. In some cases, permanent devices have also been placed without an initial trial of temporary GNM.20

Placement of a permanent electrode is more invasive and requires open or laparoscopic abdominal surgery.9,21 Electrodes are attached to the IPG and, after programming, the IPG is implanted in a subcutaneous pocket (generally, left hypochondrium). Permanent GNM has potential complications such as infection, device erosion, pain at the implantation site, perforation of the stomach/intestine, device migration and volvulus secondary to wires.6,17,20 An overall complication rate of 8.3% has been reported in the previous literature.17

Our case series is of small sample size and consisted of patients with severe symptoms of mixed aetiology. We applied temporary GNM for a short period (seven days). Each subject included in this trial was selected carefully after multiple clinical assessments and extensive investigations.

In one patient we recorded exceptionally prolonged GE, both before and after GNM (Patient 1, Table 2). This was also confirmed on endoscopic evaluations on multiple occasions as food was present in the gastric pouch several hours after ingestion. Endoscopic assessment also revealed that the pouch tissue had become fibrotic, very friable and associated with multiple ulcers. This may have been secondary to prolonged stasis of food and multiple surgeries. The possible mechanisms of extremely prolonged GE may be a vagotomy, loss of normal tissue and fibrotic conversion resulting in no or abnormal gastric slow waves. GE did not improve in Patient 1 after GNM. GE did, however, improve in three of the remaining patients.

TSS improved in all of our patients after a GNM trial. VFS improved in all patients but one, who had low pre-operative VFS. The fact that the change to GE varied so much among our patients may be due to their diverse and complex aetiologies. The change in GE may have been more consistent in patients with uniform aetiologies and a less complex surgical history. The improvement in the QOL was very subjective; the mental composite score improved in four patients and the physical composite score improved in five patients. All patients were able to eat and tolerate more food and fluids after GNM. This was confirmed with the objective evidence of increased weight after the test period.

The mechanism underlying the clinical benefits of GNM is not fully understood. It is believed that the beneficial effects are mediated by local neurostimulation and that it possibly involves the central nervous system. Other proposed mechanisms include gastric fundus relaxation and contribution of GI motility hormones.22 Some studies, however, observed only minimal acceleration in GE, suggesting that improved nausea and vomiting may not necessarily be due to an improvement in GE.21,23 We observed in two cases (Patients 1 and 5, Table 2) that clinical improvement was not associated with objective improvement in GE. Nevertheless, improvement in GE in 3 patients within 24 hours of GNM reflects that it enhanced GI motility.

The prompt and marked response in our patients with gastroparesis, intractable nausea and vomiting clearly suggests that permanent GNM is a potential long-term solution. The overall cost of one procedure is approximately £10,000 to £15,000. The case selection for a permanent device should therefore be a careful process based not only on the subjective and objective improvements after temporary GNM but also on overall cost and potential complications. Patient response to a temporary device can guide in case selection for insertion of a permanent device. Further research is justified in this field, focusing on the mechanisms of GNM and long-term outcomes of the procedure.

Conclusions

Temporary GNM improved upper GI symptoms, QOL and nutritional status in patients with intractable nausea and vomiting. It does affect GE in this chronically debilitated group of patients. More research is required to determine the indications for this procedure and to understand the mechanism of action.

References

- 1.Soykan I, Sivri B, et al. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2,398–2,404. doi: 10.1023/a:1026665728213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1,592–1,622. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkman HP, Schwartz SS. Esophagitis and gastroduodenal disorders associated with diabetic gastroparesis. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1,477–1,480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abell TL, Van Cutsem E, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation in intractable symptomatic gastroparesis. Digestion. 2002;66:204–212. doi: 10.1159/000068359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kastelik JA, Jackson W, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying in gastroesophageal reflux-related chronic cough. Chest. 2002;122:2,038–2,041. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster J, Sarosiek I, et al. Further experience with gastric stimulation to treat drug refractory gastroparesis. Am J Surg. 2003;186:690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster J, Sarosiek I, et al. Gastric pacing is a new surgical treatment for gastroparesis. Am J Surg. 2001;182:676–681. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones MP, Ebert CC, Murayama K. Enterra for gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2,578. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abell T, McCallum R, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation for medically refractory gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:421–428. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00878-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Z, Forster J, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW. Treatment of diabetic gastroparesis by high-frequency gastric electrical stimulation. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1,071–1,076. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCallum R, Lin Z, et al. Clinical response to gastric electrical stimulation in patients with postsurgical gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason RJ, Lipham J, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation: an alternative surgical therapy for patients with gastroparesis. Arch Surg. 2005;140:841–846. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.9.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Voort IR, Becker JC, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation results in improved metabolic control in diabetic patients suffering from gastroparesis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2005;113:38–42. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Csepel J, Shapsis A, Jordan C. Gastric electrical stimulation: a novel treatment for gastroparesis. JSLS. 2005;9:364–367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gourcerol G, Leblanc I, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation in medically refractory nausea and vomiting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:29–35. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000250584.15490.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maranki J, Parkman HP. Gastric electric stimulation for the treatment of gastroparesis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:286–294. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Grady G, Egbuji JU, et al. High-frequency gastric electrical stimulation for the treatment of gastroparesis: a meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2009;33:1,693–1,701. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oubre B, Luo J, et al. Pilot study on gastric electrical stimulation on surgery-associated gastroparesis: long-term outcome. South Med J. 2005;98:693–697. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000168660.77709.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayinala S, Batista O, et al. Temporary gastric electrical stimulation with orally or PEG-placed electrodes in patients with drug refractory gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:455–461. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anand C, Al-Juburi A, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation is safe and effective: a long-term study in patients with drug-refractory gastroparesis in three regional centers. Digestion. 2007;75:83–89. doi: 10.1159/000102961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abrahamsson H. Treatment options for patients with severe gastroparesis. Gut. 2007;56:877–883. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.078121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo J, Al-Juburi A, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation is associated with improvement in pancreatic exocrine function in humans. Pancreas. 2004;29:e41–e44. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200408000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abell TL, Bernstein RK, et al. Treatment of gastroparesis: a multidisciplinary clinical review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:263–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]