Abstract

Current antidepressants, which inhibit the serotonin transporter (SERT), display limited efficacy and slow onset of action. Here, we show that partial reduction of SERT expression by small interference RNA (SERT-siRNA) decreased immobility in the tail suspension test, displaying an antidepressant potential. Moreover, short-term SERT-siRNA treatment modified mouse brain variables considered to be key markers of antidepressant action: reduced expression and function of 5-HT1A-autoreceptors, elevated extracellular serotonin in forebrain and increased neurogenesis and expression of plasticity-related genes (BDNF, VEGF, Arc) in hippocampus. Remarkably, these effects occurred much earlier and were of greater magnitude than those evoked by long-term fluoxetine treatment. These findings highlight the critical role of SERT in serotonergic function and show that the reduction of SERT expression regulates serotonergic neurotransmission more potently than pharmacological blockade of SERT. The use of siRNA-targeting genes in serotonin neurons (SERT, 5-HT1A-autoreceptor) may be a novel therapeutic strategy to develop fast-acting antidepressants.

Keywords: BDNF, fast-acting antidepressants, neurogenesis, RNAi, serotonin, SERT transporter

Introduction

Despite the high prevalence of depression and its considerable socioeconomic impact, its pathophysiological mechanisms remain poorly understood.1, 2, 3 Serotonin (5-HT) participates in the etiology and treatment of major depression, being the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the most common antidepressant therapy. However, SSRIs need to be administered for long time periods before clinical improvement emerges, and fully remit depressive symptoms in only one third of patients.4, 5, 6

The serotonin transporter (SERT) is a key regulator of serotonergic neurotransmission, as it controls the active fraction of 5-HT. In the brain, SERT is localized to raphe 5-HT neurons at somatodendritic and terminal levels.7, 8, 9 SERT blockade by SSRIs (showing nM affinity for SERT)10 initiates the chain of events leading eventually to clinical improvement. Long-term SSRI treatment promotes an internalization of SERT from the cell surface in 5-HT neurons without affecting SERT mRNA expression.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In addition to loss of 5-HT1A-autoreceptor function,16, 17, 18 SERT down-regulation may enhance forebrain 5-HT neurotransmission contributing to the therapeutic action of SSRIs.19, 20

Polymorphic variations in SERT transcriptional region—leading to reduced SERT expression and function—are involved in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders, including major depression,21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and in the clinical response to SSRI.26, 27 SERT-knockout mice were generated to gain further insight into the role of SERT in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression.28, 29 However, these mice showed depression-related behaviors attributable to the developmental changes that result from SERT early-life absence and the perturbed 5-HT function.30, 31, 32 Thus, while SERT-knockout mice represent a useful model to investigate disorders involving genetic alterations in SERT during early life, they are less appropriate to study downstream changes of 5-HT transmission secondary to SERT blockade in adulthood.

RNA interference (RNAi) has a critical role in regulating gene expression.33, 34 It also provides new alternatives to pharmacological treatments to modulate brain neurotransmission through the use of exogenous small interference RNA (siRNA). Recent studies have shown the feasibility to silence the expression of critical genes in 5-HT neurons, such as SERT and the 5-HT1A-autoreceptor.18, 35 Given the above limitations of SERT-knockout mice, here we evaluated the specificity and selectivity of partial SERT suppression in adult mice, following short-term SERT-siRNA treatment. We examined downstream changes on brain variables linked to antidepressant efficacy and compared SERT-siRNA effects with those of a standard SSRI (fluoxetine) treatment. The results indicate that the post-transcriptional regulation of SERT may constitute a target for fast-acting antidepressants, thus bringing RNAi closer to the clinic as a potential therapy for major depression.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (10–14 weeks; Charles River, Lyon, France) were housed under controlled conditions (22±1 °C; 12 h light/dark cycle) with food and water available ad libitum. Animal procedures were conducted in accordance with standard ethical guidelines (EU regulations L35/118/12/1986) and approved by the local ethical committee.

Drug/siRNA treatments

SERT-targeting siRNA (nt:1230–1250, GenBank accession NM_010484) and an unrelated siRNA with no homology to mouse genome (nonsense siRNA, ns-siRNA) were used (Life Technology, Madrid, Spain). The siRNA sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Mice were anesthetized (pentobarbital, 40 mg kg−1, intraperitoneally, i.p.) and silica capillary microcannula (110 μm-outer diameter (OD), 40 μm-inner diameter (ID); Polymicro Technologies, Madrid, Spain) were stereotaxically implanted into the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR; coordinates in mm: anteroposterior, −4.5; mediolateral, −1.0; dorsoventral, −4.4; with a lateral angle of 20°).36 Local siRNA microinfusion was performed with a perfusion pump at 0.5 μl min−1 24 h after surgery in awake mice as described previously.18 siRNAs were prepared in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (125 mℳ NaCl, 2.5 mℳ KCl, 1.26 mℳ CaCl2 and 1.18 mℳ MgCl2 with 5% glucose) and infused intra-DR once daily at the dose of 10 μg μl−1 (0.7 nmol per dose). Mice received two dose in 2 consecutive days, or four dose in 5 days (days 1, 2, 4 and 5), and were killed on 3rd or 6th day, respectively. An additional group of mice received seven dose in 9 days (days 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 9) and was killed on 10th-day. In the last group, only in situ hybridization and autoradiography studies were performed (see below). Control mice received artificial cerebrospinal fluid.

Fluoxetine (Tocris, Madrid, Spain) was prepared in saline and was administered once daily at 20 mg kg−1 dose, i.p. for 4, 7 or 15 days. Mice were killed on 5th, 8th or 16th day, respectively. Control mice received saline.

In situ hybridization and autoradiographic studies

Tissue preparation

Mice were killed by pentobarbital overdose and brains rapidly removed, frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C. Tissue sections (14 μm thick-coronal) were cut using a microtome-cryostat (HM500-OM, Microm, Walldorf, Germany), thaw-mounted onto 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain)-coated slides and kept at −20 °C until use.

In situ hybridization

Antisense oligoprobes [33P]-labeling and in situ hybridization procedures were carried out as described previously.18 Mouse SERT, 5-HT1AR, tryptophan hydroxylase 2, Ki-67, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), activity-regulated cytoskeletal protein (Arc), and cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) probes were synthesized by IBA-GmbH (Göttingen, Germany). Details can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Receptor autoradiography

The autoradiographic binding assays for 5-HT1AR, SERT and norepinephrine transporter were performed using the following radioligands: (a) [3H]-8-OH-DPAT (233 Ci mmol−1), (b) [3H]-citalopram (70 Ci mmol−1) and (c) [3H]-nisoxetine (85 Ci mmol−1), respectively (Perkin-Elmer, Madrid, Spain).18, 37 Experimental conditions are summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

5-HT1AR-stimulated [35S]GTPγS autoradiography

Labeling of DR sections with [35S]GTPγS was performed as described previously.38 Autoradiograms were analyzed and the relative optical densities (ROD) were obtained using a computer-assisted image analyzer (AIS, Imaging Research, St Catherines, Ontario, Canada). Details are shown in Supplementary information.

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine administration

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain) and dissolved in saline solution. Mice were injected with 4 × 75 mg kg−1 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine every 2 h, i.p., the last day of antidepressant treatments. Mice were killed 24 h later.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in sodium-phosphate buffer (pH=7.4). Brains were collected, post-fixed 24 h at 4 °C in the same solution, and then placed in gradient sucrose or phosphate-buffered saline 10–30% for 2 days at 4 °C. After cryopreservation, 30-μm-thick free-floating coronal brain sections were processed for immunohistochemical visualization of SERT, BdrU, Ki-67, NeuroD, NeuN, Doublecortin (DCX), GFAP and IBA-1 by using the biotin-labeled antibody procedure. Details are shown in Supplementary Information.

Intracerebral microdialysis

Extracellular serotonin concentration was measured by in vivo microdialysis.18, 39 Details are shown in the Supplementary Information.

Tail suspension test

Mice were moved from the housing room to the testing area in their home cages and allowed to adapt to the new environment for at least 1 h before testing. Mice were suspended 30 cm above the bench by adhesive tape placed ∼1 cm from the tip of the tail. The total duration of immobility during a 6 min test was measured.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. Data were analyzed with Student's t-test, one- two- or three-way analysis of variance as appropriate followed by post-hoc test (Newman-Keuls). The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

In vivo characterization of SERT knockdown in mice

We first examined the feasibility to acutely suppress in vivo SERT expression in raphe 5-HT neurons using a SERT-siRNA. Mice were locally infused with: (a) vehicle, (b) ns-siRNA or (c) SERT-siRNA (10 μg per dose) into DR for 2 consecutive days using a protocol similar to that inducing 5-HT1A-autoreceptor knockdown.18, 40 Histological analysis revealed a significant decrease of SERT expression in DR—but not in median raphe nucleus (MnR)—of SERT-siRNA-treated mice (SERT mRNA and binding levels were 63±4% and 70±8%, respectively versus vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice). Neither treatment altered the raphe expression of norepinephrine transporter, 5-HT1AR and tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (Supplementary Figure S1a–d).

Next, we evaluated the potential neurotoxic effects of SERT-siRNA infusion by immunohistochemical staining for NeuN, GFAP and IBA-1 (neuronal, astrocyte and microglial markers, respectively). Compared with control groups (ns-siRNA and vehicle), SERT-siRNA-treated mice showed no loss of NeuN-positive neurons in DR. In addition, a mild increase in DR GFAP was noted in all experimental groups, likely due to the reactive astrogliosis secondary to the microcannula implant. Likewise, IBA-1-stained sections in each group showed no increase in activated microglia, except for within the injection tracts (Supplementary Figure S2a–c).

The functional impact of siRNA-induced acute SERT reduction was assessed by in vivo microdialysis in caudate putamen (CPu), a forebrain area exclusively innervated by DR 5-HT fibers.41 Local 50 μℳ veratridine application produced a similar increase of extracellular 5-HT in CPu of all groups, indicating that SERT knockdown did not alter the impulse-dependent 5-HT release. However, 1 μℳ citalopram (SSRI) infusion by reverse dialysis increased 5-HT concentration in CPu of vehicle (170±27% of baseline) and ns-siRNA-treated mice (180±15%), but not of SERT-siRNA-treated mice (83±8%), reflecting a decreased SERT expression/function in the latter group (Supplementary Figure S3a). In addition, fluoxetine administration (SSRI; 20 mg kg−1, i.p.) enhanced extracellular 5-HT in CPu of vehicle-treated mice (8.0±1.0 fmol per fraction), reaching the basal values in SERT-siRNA-treated mice (10.0±0.6 fmol per fraction) (Supplementary Figure S3b). Next, the efficacy of SERT-siRNA infusion was tested in the tail suspension test, a highly reliable predictor of clinical antidepressant potential.42, 43 Mice treated with SERT-siRNA showed a significant reduction of the immobility time compared with control groups (Supplementary Figure S3c).

Different regulation of SERT mRNA and protein levels after SERT-siRNA or fluoxetine treatment

Following verification the effectiveness of SERT suppression by acute SERT-siRNA, we evaluated the effect on SERT regulation after short-term SERT-siRNA administration and its time course. Mice were infused intra-DR with four- or seven-dose SERT- or ns-siRNA (10 μg per dose) or vehicle during 5 and 9 days, respectively. The effects on SERT expression were compared with those in mice treated with fluoxetine (20 mg kg−1 per day, i.p.) or saline for 4, 7 or 15 days.

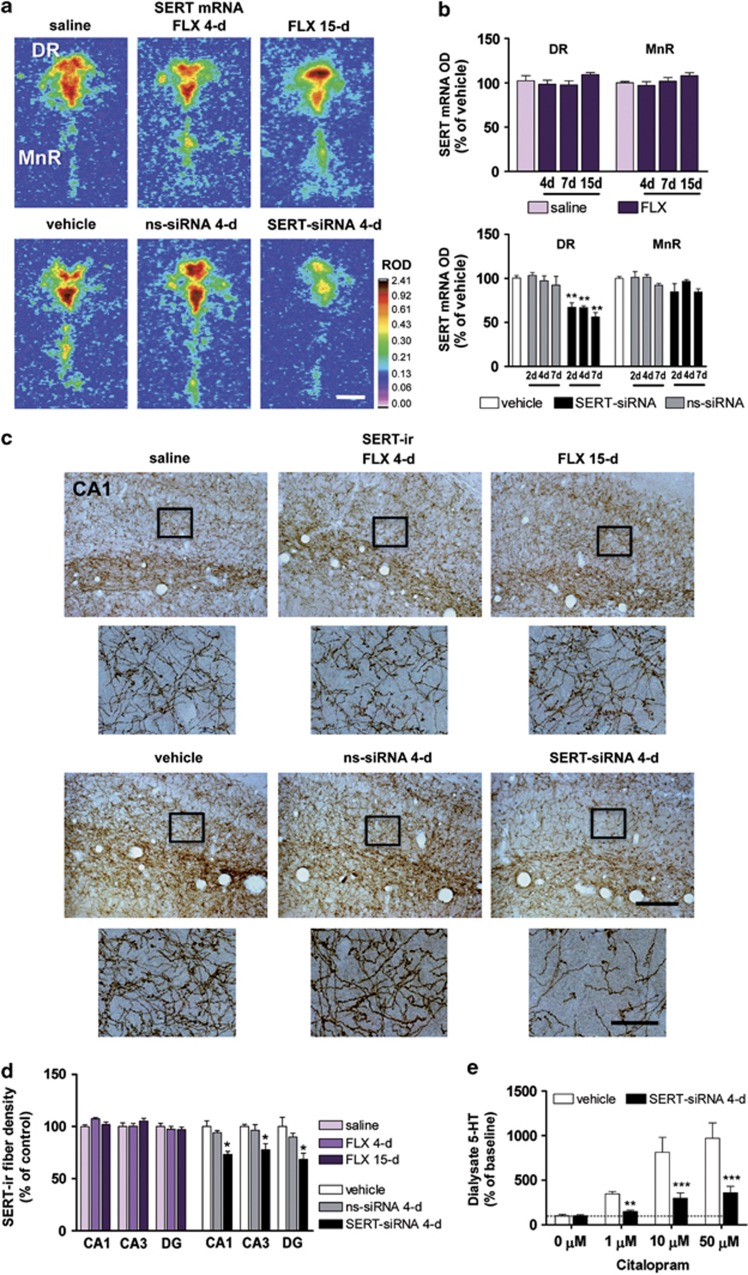

Short-term SERT-siRNA infusion evoked a regionally selective (only in DR) and dose-dependent reduction of SERT mRNA expression. This reduction was not observed in control mice (vehicle and ns-siRNA) nor in any of the fluoxetine-treated groups (Figures 1a and b). As SERT is localized in the somatodendritic and terminal regions of raphe 5-HT neurons,7 [3H]-citalopram autoradiography was performed to quantify SERT-binding sites in different brain regions along the rostro-caudal axis. Repeated SERT-siRNA infusion, but not ns-siRNA, significantly reduced SERT binding by ∼30%–40% in most brain regions analyzed. Differences in the extent of the reduction likely reflect the DR/MnR origin of serotonergic fibers in each region (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Serotonin transporter-small interference RNA (SERT-siRNA) treatment, but not fluoxetine (FLX), downregulates SERT mRNA and protein levels. Mice were infused with two-, four- or seven-dose SERT- or nonsense siRNA (ns-siRNA) (10 μg–0.7 nmol per day) or vehicle into the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR). Other groups of mice were treated with 4, 7 or 15-day FLX (20 mg kg−1 per day, intraperitoneally) or saline. (a) Representative coronal brain sections showing reduced SERT expression in the DR of mice treated with SERT-siRNA (four dose), but not with FLX, as assessed by in situ hybridization. Scale bar=500 μm. (b) Bar graphs showing no differences in SERT mRNA level in DR and median raphe nucleus (MnR) of FLX-treated mice. However, SERT-siRNA at different doses significantly reduced SERT mRNA level exclusively in DR (n=5–10 mice per group). Two-way analysis of variance revealed a significant effect of group (F2,33=59.32, P<0.001). (c) Representative images of SERT-immunoreactive (SERT-ir) axons in the hippocampal CA1 region. Short-term SERT-siRNA treatment (four dose) significantly decreased the target SERT protein density as compared with vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice. In contrast, FLX treatment did not alter SERT-ir axon density. Box insets represent regions of high-magnification photomicrographs. Scale bars: lower magnification=100 μm and high magnification=20 μm. (d) SERT-ir fiber density in different hippocampal subfields including CA1, CA2, CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) was measured and expressed as the percentage of the density in the respective vehicle-treated mice (n=4–6 mice per group). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of group (F2,11=11.16, P<0.01). (e) Local citalopram (SSRI) infusion by reverse dialysis induced a concentration-dependent increase of extracellular 5-HT in caudate putamen (CPu) of vehicle-treated mice (n=7). However, this effect was lesser marked in SERT-siRNA-treated mice (n=9). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of group (F1,14=17.17, P<0.0001), concentration (F3,42=27.06, P<0.0001) and group-by-concentration interaction (F3,42=7.72, P<0.0001). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice. Values are mean±s.e.m.

In contrast, a specific [3H]-citalopram signal was undetectable in fluoxetine-treated mice (4, 7 or 15 days), likely owing to the long half-life of fluoxetine. Additional SERT autoradiography binding was performed in fluoxetine-treated mice (4 or 7-day) and subjected to a 48–96 h washout before killed to reduce fluoxetine serum concentrations.13, 44 Even in these conditions, a specific [3H]-citalopram binding was not observed (data not shown).

Next, we examined the density of SERT-containing fibers in several brain areas, including different hippocampus (HPC) subfields (Figure 1c and Supplementary Figure S5) where neurogenesis was evaluated (see below). Short-term SERT-siRNA treatment (four dose) caused a rapid and significant decrease of SERT-immunolabeling in different HPC areas relative to vehicle- and ns-siRNA-treated mice. However, SERT-immunolabeling was equal in fluoxetine-treated mice and their respective controls (Figures 1c and d). The presence of an immunohistochemical SERT signal in fluoxetine-treated mice indicates that the lack of specific [3H]-citalopram binding was due to competence with fluoxetine present in the tissue sections. Likewise, these data highlight the different mechanism of regulation of SERT expression. Thus, whereas SERT-siRNA-induced post-transcriptional changes lead to SERT mRNA knockdown and a subsequent fall in protein density, we did not find an effect of fluoxetine on SERT expression, as previously reported.45, 46

In agreement with this partial SERT suppression, a decreased SERT function was observed in SERT-siRNA-treated mice (four dose). Hence, local application of citalopram (1–10–50 μℳ) produced much smaller increases of extracellular 5-HT in the CPu relative to vehicle controls (Figure 1e).

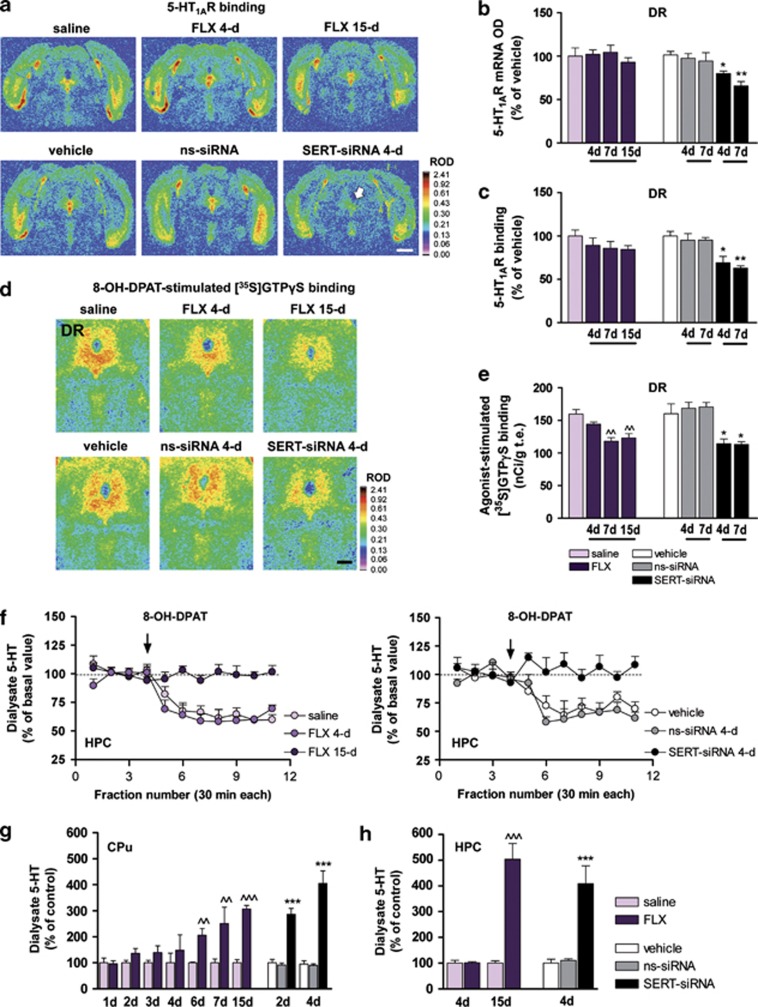

Short-term SERT-siRNA treatment, but not fluoxetine, reduces 5-HT1A-autoreceptor expression and function

The functional down-regulation of presynaptic 5-HT1AR (5-HT1A-autoreceptors) is required for the clinical antidepressant action.16, 38, 47, 48 Indeed, the degree of 5-HT1AR-mediated inhibition of 5-HT by SSRIs has been used as a reliable index of their sensitivity.49, 50 As expected, 5-HT1A-autoreceptor expression was unchanged in any of the fluoxetine-treated groups (Figures 2a–c). However, 7 and 15-day fluoxetine administration (but not 4-day) attenuated 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the DR, indicating a decrease in G-protein coupling efficiency of 5-HT1AR (Figures 2d and e). In contrast, a short-term SERT-siRNA treatment significantly reduced 5-HT1A-autoreceptor expression and produced a concomitant loss of function as assessed by [35S]GTPγS binding (Figures 2a–e).

Figure 2.

(a–f) Short-term serotonin transporter-small interference RNA (SERT-siRNA) treatment, but not fluoxetine (FLX), reduces 5-HT1A-autoreceptor expression and function. Mice were infused with four or seven dose SERT- or nonsense siRNA (ns-siRNA; 10 μg per day) or vehicle into dorsal raphe nucleus (DR). Other groups of mice were treated with 4, 7 or 15-day FLX (20 mg kg−1 per day, intraperitoneally (i.p.) or saline. (a) Representative coronal midbrain sections showing [3H]-8-OH-DPAT binding to 5-HT1AR in DR. The arrow indicates the decreased DR 5-HT1AR density in SERT-siRNA-treated mice (four dose). Scale bar=2 mm. (b) Bar graphs showing no differences in DR 5-HT1AR mRNA levels of vehicle- and FLX-treated mice. However, SERT-siRNA significantly reduced 5-HT1AR mRNA level in DR compared with vehicle and ns-siRNA groups (n=3–5 mice per group). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed an effect of group (F2,15=22.59, P<0.001). (c) Quantitative [3H]-8-OH-DPAT binding showed a decreased DR 5-HT1AR density after SERT-siRNA treatment, but not with FLX (n=4–7). Two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of group (F2,15=20.69, P<0.001). (d) Autoradiograms of coronal midbrain sections of mice showing 5-HT1AR 8-OH-DPAT agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Scale bar=500 μm. (e) FLX induced a decreased DR 8-OH-DPAT-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding from days 7 to 15 of treatment (n=5–8). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of group (F3,25=11.40, P<0.001). However, SERT-siRNA produced a fast 5-HT1A-autoreceptor desensitization detected after four dose treatment (n=4–8). Two-way ANOVA revealed an effect of group (F2,31=10.47, P<0.001). (f) The 5-HT1AR agonist 8-OH-DPAT (0.5 mg kg−1, i.p.) decreased extracellular 5-HT concentration in ventral hippocampus (HPC) of saline- and FLX-treated mice (4-day), but not after 15-day FLX treatment (n=5–9). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of group (F2,18=41.32, P<0.0001), time (F10,180=13.96, P<0.001) and interaction (F20,180=4.41, P<0.001). Similarly, 8-OH-DPAT had no effect on ventral HPC 5-HT release in SERT-siRNA-treated mice (four-dose), unlike to control groups (n=4). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of group (F2,8=23.13, P<0.0001), time (F10,80=6.38, P<0.001) and interaction (F20,80=4.41, P<0.001). (g–h) Time course of the increase in extracellular 5-HT levels in forebrain. Mice received an intra-DR infusion of two or four dose siRNA or vehicle. Microdialysis experiments were performed on the 3rd or 6th day, respectively. In addition, groups of mice were treated with FLX (20 mg kg−1 per day, i.p.) or saline and microdialysis experiments were performed 24 h after the last administration on 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th, 8th and 16th day. (g) FLX treatment significantly increased extracellular 5-HT levels in caudate putamen (CPu) from six dose onwards, compared with saline-treated mice (F13,80=7.43, P<0.0001; n=7–10 mice per group). In contrast, SERT-siRNA-treated mice displayed a larger and faster increase in CPu 5-HT levels, which was significantly different from control already after two-dose treatment (F5,60=32.52, P<0.0001; n=7–12 mice per group). (h) Long-term FLX treatment (15 dose) also increased 5-HT levels in ventral HPC compared with saline-treated mice (F3,20=39.93, P<0.0001; n=4–9). SERT-siRNA-treated mice (four dose) also showed a rapid and significant increase of HPC 5-HT levels relative to vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice (F2,18=14.51, P<0.001; n=4–9 mice). ^^P<0.01, ^^^P<0.001 versus saline-treated mice; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice. Values are mean±s.e.m.

Likewise, the 5-HT1AR agonist 8-OH-DPAT (0.5 mg kg−1, i.p.) significantly decreased 5-HT release in the HPC of vehicle (62±4% of baseline) and mice treated with fluoxetine for 4 days (61±4%), but not in those treated for 15 days (99±2%) (Figure 2f). Interestingly, 8-OH-DPAT did not reduce hippocampal 5-HT release in four-dose SERT-siRNA-treated mice (103±5% of baseline), unlike in control groups (vehicle: 70±3% and ns-siRNA: 65±2%) (Figure 2f). This indicates a very fast attenuation of 5-HT1A-autoreceptor sensitivity in SERT-siRNA-treated mice, as observed after long-term pharmacological blockade of SERT.47, 51

Time course of forebrain extracellular 5-HT concentration after SERT-siRNA or fluoxetine treatment

We next assessed the kinetics of extracellular 5-HT levels after SERT-siRNA or fluoxetine treatment using in vivo microdialysis. Basal extracellular 5-HT levels in CPu and HPC of control mice were: 3.4±0.3 fmol per fraction (n=49) and 1.7±0.1 fmol (n=9) per fraction, respectively. Further, baseline 5-HT levels of mice implanted with a silica microcannula into DR were: 3.9±0.4 fmol per fraction (CPu, n=25) and 2.4±0.5 fmol per fraction (HPC, n=10). No significant differences were detected between groups.

Repeated fluoxetine administration induced a progressive and significant increase of 5-HT levels in CPu from days 6 to 15 of treatment compared to their respective saline-treated controls (Figure 2g). SERT-siRNA-treated mice displayed a larger and faster increase in CPu 5-HT levels, which was not seen in control groups. Extracellular 5-HT in CPu of mice treated with four doses of SERT-siRNA was greater than after 15-day fluoxetine administration (Figure 2g). Similar results were seen in HPC, where SERT-siRNA (four doses) increased extracellular 5-HT to the same extent than a 15-day treatment with fluoxetine (Figure 2h). Regional differences are likely owing to the greater contribution of DR axons in CPu versus HPC.52

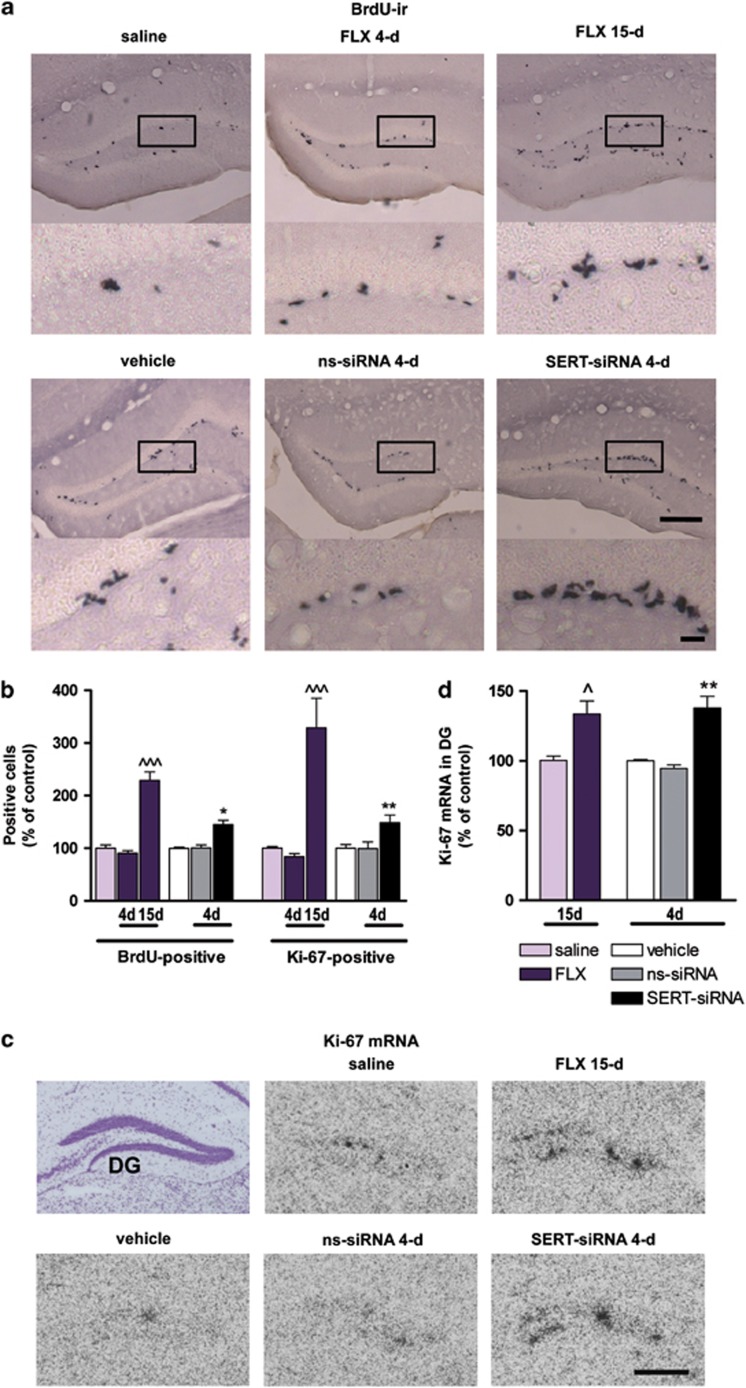

SERT-siRNA treatment induces faster adult neurogenesis than fluoxetine

We then addressed whether the above temporal differences between SERT-siRNA and fluoxetine translated into the proliferative activity in dentate gyrus (DG), a key feature of antidepressant treatments. To this end, mice were injected with the proliferation marker BdrU on the last day of the antidepressant treatments. Twenty-four hours later, BdrU incorporation was quantified in DG. Remarkably, SERT-siRNA (four dose) significantly enhanced the number of BdrU-labeled cells to 144±8% of vehicle-treated mice. No effect was observed in ns-siRNA-treated mice (Figures 3a and b). Detailed morphological analysis revealed that these cells were grouped in clusters, suggesting an acute induction of mitotic activity. Such clusters of BdrU-positive cells were detectable after 15-day (but not 4-day) fluoxetine treatment (BdrU-positive cells: 91±5 and 229±16% following 4- and 15-day fluoxetine relative to saline group) (Figures 3a and b). Moreover, we confirmed the effects on neural progenitor cell proliferation, assessing the intrinsic Ki-67 expression in DG.53, 54 Both Ki-67 mRNA level and Ki-67-positive cells were significantly increased in the DG of SERT-siRNA- and fluoxetine-treated mice following 4 and 15-day of administration, respectively, compared with their control groups (Figures 3b–d).

Figure 3.

Serotonin transporter (SERT) silencing accelerates neural proliferation in the adult hippocampus compared with fluoxetine (FLX). Mice were infused with four dose SERT- or nonsense siRNA (ns-siRNA; 10 μg per day) or vehicle into dorsal raphe nucleus (DR). Other groups of mice were treated with 4 or 15-day FLX (20 mg kg−1 per day, intraperitoneally) or saline. (a) Representative images showing an increased number of 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BdrU)-positive cells in the dentate gyrus (DG) of FLX-treated mice (15-day) or serotonin transporter-small interference RNA (SERT-siRNA)-treated mice (four dose) compared with their respective control mice. Box insets frame regions of high-magnification photomicrographs shown below. Scale bars: lower magnification=100 μm and high magnification=20 μm. (b) Cell proliferation was assessed by the number of BdrU-positive cells (n=5–8 mice) and Ki-67-positive cells (n=5–9 mice) in the granule cell layer. Quantitative analysis indicated a significant increase in both BdrU- and Ki-67-positive cell number for longer treatment with FLX (BdrU: F2,20=53.16; Ki-67: F2,17=20.72) or SERT-siRNA (BdrU: F2,13=14.10; Ki-67: F2,18=6.26). (c) Representative coronal brain sections showing Ki-67 expression in DG assessed by in situ hybridization. Scale bar=100 μm. (d) Bar graph showing increased Ki-67 mRNA levels in DG following FLX (15-day) and SERT-siRNA (four dose) treatment as compared with respective control groups (n=3–4 mice). One-way analysis of variance revealed a significant effect of group (F4,11=9.73, P<0.01). ^P<0.05, ^^^P<0.001 versus saline-treated mice; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice. Values are mean±s.e.m.

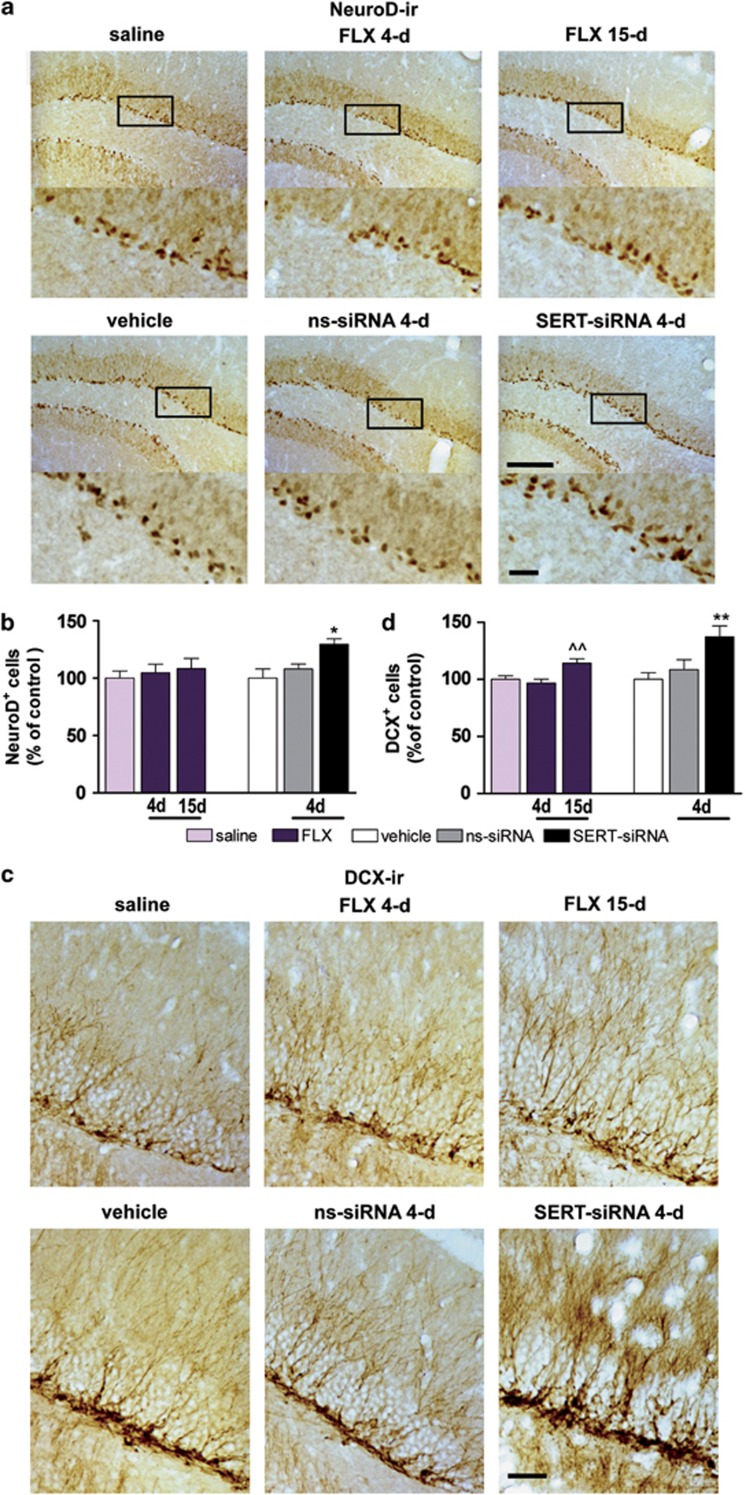

In addition, an increase in NeuroD-positive cells was seen in the subgranular cell layer of DG after four-dose SERT-siRNA treatment (129±5% of vehicle), whereas fluoxetine administration (15-day) led to a slight, but non-significant increase in the number of immature neurons (NeuroD-positive cells: 115±10% of vehicle) (Figures 4a and b). To assess whether SERT-siRNA regulates neuronal cell migration, DCX-immunostaining was performed. SERT-siRNA treatment (four-dose) significantly enhanced the number of DCX-positive cells in the DG (137±9% of vehicle) compared with control groups. Similar data were obtained after 15-day fluoxetine administration (DCX-positive cells: 121±4% of vehicle) (Figures 4c and d).

Figure 4.

Serotonin transporter (SERT) silencing rapidly increases the number of NeuroD- and DCX-positive cells in hippocampus. Mice were infused with four dose SERT- or nonsense siRNA (ns-siRNA; 10 μg per day) or vehicle into dorsal raphe nucleus (DR). Other groups of mice were treated with 4 or 15-day fluoxetine (FLX; 20 mg kg−1 per day, intraperitoneally) or saline. (a) Immunohistochemical images showing NeuroD-positive progenitors in the dentate gyrus (DG) of mice. Box insets represent regions of high-magnification photomicrographs. Scale bars: lower magnification=100 μm and high magnification=20 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis indicated a significant increase in the number of NeuroD-positive cells in serotonin transporter-small interference RNA (SERT-siRNA)-treated mice (four dose) compared with vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice (n=5–9 mice). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed an effect of group (F2,11=5.87, P<0.05). (c) Representative photomicrographs showing DCX-positive cells, bearing a complex dendritic morphology in the DG of mice. Scale bar=20 μm. (d) Quantitative analysis revealed a significant increase in the number of DCX-positive cells in both 15-day FLX (F2,29=7.71, P<0.01) and four dose SERT-siRNA-treated mice (F2,18=5.94, P<0.05) (n=6–10). ^^P<0.01 versus saline-treated mice; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice. Values are mean±s.e.m.

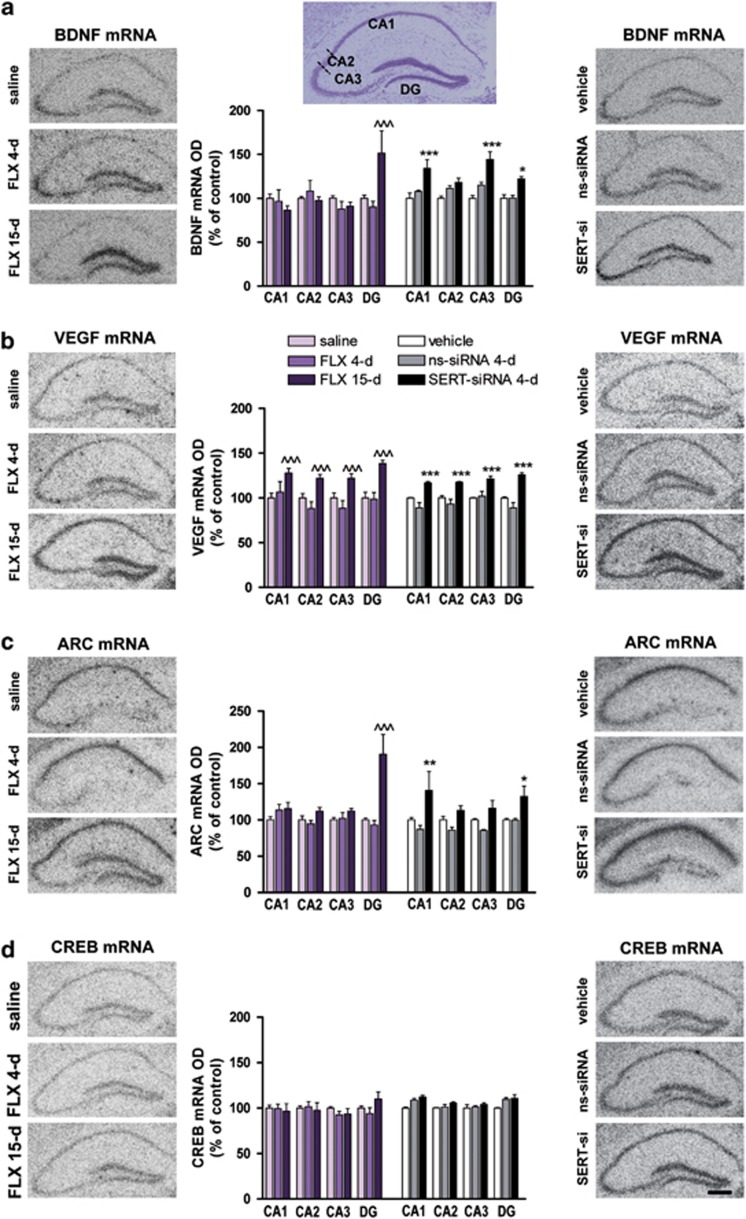

Short-term SERT-siRNA treatment, but not fluoxetine, enhances hippocampal plasticity-associated gene expression

As the final step of the present study, we assessed whether SERT-siRNA (four dose) was able to increase the hippocampal expression of trophic factors such as BDNF and VEGF, which are known to be enhanced only after prolonged (2–3 weeks) antidepressant treatments.55, 56, 57 We also examined the effects on the expression of the immediate early gene Arc and the transcription factor CREB, which are also regulated by chronic antidepressant treatments and contribute to the antidepressant efficacy.58, 59 We found that SERT-siRNA infusion (four dose) robustly and significantly increase BDNF mRNA levels in the different hippocampal areas (CA1: 134±9%, CA3: 144±9% and DG: 122±2% of vehicle) (Figure 5a). A 15-day fluoxetine treatment (but not 4-day) increased BDNF mRNA expression only in DG (151±25%). Likewise, SERT-siRNA (four dose) significantly enhanced VEGF expression in all HPC subfields (∼125%), as produced by 15-day fluoxetine treatment (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Serotonin transporter (SERT) silencing enhances hippocampal plasticity-associated gene expression. Mice were infused with four dose SERT- or nonsense siRNA (ns-siRNA; 10 μg per day) or vehicle into dorsal raphe nucleus (DR). Other groups of mice were treated with 4 or 15-day fluoxetine (FLX; 20 mg kg−1 per day, intraperitoneally) or saline. (a–d) Representative autoradiograms of hippocampal sections of mice are shown for (a) brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), (b) vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), (c) activity-regulated cytoskeletal protein (Arc) and (d) cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) mRNA expression. Scale bar=100 μm. Densitometric analyses were performed in different hippocampal regions: CA1, CA2, CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG), shown in the cresyl violet-stained section (top). Levels of mRNA for each gene are shown in the bar graphs next to the representative autoradiograms (n=4–5 mice). (a) BDNF mRNA levels in DG were significantly increased after 15-day FLX treatment compared with saline-treated mice (two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA): effect of region F3,33=5.76 and interaction group-by-region F6,33=7.86). However, serotonin transporter-small interference RNA (SERT-siRNA) treatment (four dose) increased BDNF expression in CA1, CA3 and DG compared with respective control groups (significant effect of group F2,8=18.03 and region F3,24=4.33). (b) VEGF mRNA levels were augmented in all hippocampal subfields after FLX (15-day) or SERT-siRNA (four dose) treatments compared with respective control groups (two-way ANOVA; FLX: effect of group F2,10=10.11, region F3,30=12.80 and interaction F6,30=4.54; SERT-siRNA: effect of group F2,8=17.32, region F3,24=5.00 and interaction F6,24=5.42). (c) Arc mRNA levels in DG were significantly increased following FLX (15-day) compared with saline-treated mice (two-way ANOVA: effect of group F2,11=9.30, region F3,33=4.93 and interaction group-by-region F6,33=7.75). SERT-siRNA treatment (four dose) increased Arc expression in CA1 and DG compared with respective control groups (significant effect of group F2,13=11.53, region F3,39=6.77 and interaction F6,39=4.05). (d) CREB mRNA levels were unchanged following any treatment. ^^^P<0.001 versus saline-treated mice; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus vehicle and ns-siRNA-treated mice. Values are mean±s.e.m.

Furthermore, SERT-siRNA (four dose) significantly upregulated the Arc mRNA expression in CA1 and DG (∼135%), an effect that was observed in DG only after 15-day fluoxetine treatment (190±27%) (Figure 5c). In contrast to these changes, neither SERT-siRNA nor fluoxetine altered hippocampal CREB mRNA expression (Figure 5d).

Discussion

The present study shows that partial RNAi-based reduction of SERT expression in mouse DR has dramatic effects on serotonergic neurotransmission. Short-term SERT-siRNA treatment evoked a number of changes in behavioral, neurochemical and cellular variables predictive of therapeutic antidepressant activity, such as (i) reduced immobility time in the tail suspension test, (ii) increased extracellular 5-HT concentration, (iii) downregulated 5-HT1A-autoreceptor expression/function, (iv) enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis and (v) increased hippocampal expression of plasticity-associated genes. Remarkably, these changes occurred much earlier and were in general of greater magnitude than those evoked by long-term SSRI-fluoxetine administration. Together with earlier reports,18, 35, 40 this study illustrates the therapeutic potential of siRNA-based strategies in the treatment of major depression. In particular, our data highlight the relevance of post-transcriptional SERT regulation as a new therapeutic approach to develop fast-acting antidepressants.

We previously showed that unmodified siRNA infusion into the mouse DR and also, intracerebroventricular or intranasal administration of a conjugated siRNA can efficiently and selectively reduce 5-HT1A-autoreceptor expression in 5-HT neurons, thus evoking antidepressant responses.18, 40 Here, we suppressed SERT expression, another key mechanism controlling brain serotonergic transmission. RNAi-induced reduction of SERT level triggers remarkable effects on serotonergic function, faster and more efficient than those produced by the pharmacological SERT blockade. Thus, forebrain 5-HT concentration was increased three- and four-fold by two and four doses of SERT-siRNA, respectively, an effect similar to that found after 2-week fluoxetine treatment at a daily dose showing ∼90% SERT occupancy.60 The robust effect on extracellular 5-HT, compared with the relatively modest change in SERT expression (consistent with its half-life, ∼3 days),61 suggests that functional SERT derives from newly synthesized pools.

As expected from the increased serotonergic function, resulting from the decreased SERT level, mice treated with very small SERT-siRNA (1.4 nmol) showed a marked reduction of immobility in the tail suspension test, a behavioral response evoked by antidepressant drugs.18, 42 An earlier study also found antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test but after a prolonged intracerebroventricular SERT-siRNA infusion during 2-week at a higher dose (31 nmol per day).35 Overall, this indicates that SERT knockdown in adulthood significantly improves the resilience to stress, thus contributing to the antidepressant action.

The fast increase of extracellular 5-HT observed in SERT knockdown mice likely accounts for the rapid desensitization of 5-HT1A-autoreceptors, a key characteristic of antidepressant drugs. Indeed, 5-HT1A-autoreceptor stimulation by the excess 5-HT produced by SSRIs reduces raphe 5-HT neuronal firing and, consequently, 5-HT neurotransmission in forebrain.16 Only after successful 5-HT1A-autoreceptor desensitization, 5-HT neuron activity and terminal 5-HT release are recovered.17, 47 In agreement with these previous studies, fluoxetine desensitized 5-HT1A-autoreceptors after 2-week treatment. Interestingly, short-term SERT-siRNA treatment fully disrupts the 5-HT1A-autoreceptor function and—unlike fluoxetine—decreases their expression in DR, thus hastening the adaptive presynaptic mechanisms in serotonergic neurotransmission.

The fast-acting antidepressant potential of SERT-siRNA was further confirmed by its ability to increase neurogenesis and to activate the expression of plasticity gene in the adult mouse HPC. It is well accepted that antidepressants share the common property to positively modulate cellular growth and plasticity in mood-related brain areas. Indeed, plasticity-associated gene expression and neurogenesis are considered to be specific markers of antidepressant action.56, 57, 58, 59 However, these effects require prolonged (for example, >2 weeks) administration of antidepressants drugs.62, 63, 64 One of the more relevant findings of the present study is the observation that short-term SERT-siRNA treatment increased hippocampal progenitor proliferation using two different markers (5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine and Ki-67), an effect produced only after 15-day pharmacological SERT blockade. This was accompanied by an increase in the number of NeuroD- and DCX-positive cells, whose morphological complexity suggests that the integration of immature neurons into hippocampal networks may be accelerated by SERT-siRNA. In parallel, SERT-siRNA ( four dose)—but not fluoxetine—, also enhanced the expression of trophic factors such as BDNF and VEGF, as well as that of the activity-dependent Arc gene in several HPC subfields. Neuronal activity recruits latent stem/progenitor cells in the adult HPC, increasing the expression of trophic factors.65 Therefore, these could serve to link neuronal activity to structural plasticity in the hippocampal neurogenic niche. Future experiments will examine whether this neurogenic effect is required for the antidepressant-like responses elicited by SERT-siRNA treatment.

In conclusion, our results show that siRNA-induced selective SERT knockdown evokes a number of behavioral, neurochemical and cellular responses predictive of clinical antidepressant activity. Notably, these effects occur after short-term SERT-siRNA treatment and are remarkably faster and—in most instances—more effective than those elicited by persistent SERT blockade with the SSRI fluoxetine. Together with previous observations,18, 35, 40 the present data support the usefulness of RNAi strategies, stimulating serotonergic transmission as a new therapeutic class overcoming the two main limitations of current pharmacological treatments, that is, limited efficacy and slowness of action.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation—CDTI, with the participation of the DENDRIA Consortium; from Instituto de Salud Carlos III PI10/00290 and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM, P91C). Structural funds of the European Union, through the National Applied Research Projects (R+D+I 2008/11) and from the Catalan Government (grant 2009SGR220) are also acknowledged. We gratefully thank to Mireia Galofré and Esther Ruiz-Bronchal for technical support and, Anna Castañé for advice in behavioral test.

FA has received consulting and educational honoraria on antidepressant drugs from Eli Lilly and Lundbeck. AM is a cofounder and board member of nLife Therapeutics S.L. MCC is an employee of nLife Therapeutics S.L. The rest of authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature. 2008;455:894–902. doi: 10.1038/nature07455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. Trillion-dollar brain drain. Nature. 2011;478:15. doi: 10.1038/478015a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ML, Licinio J. Research and treatment approaches to depression. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:343–351. doi: 10.1038/35072566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, Quitkin F, Warden D, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1243–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakely RD, De Felice LJ, Hartzell HC. Molecular physiology of norepinephrine and serotonin transporters. J Exp Biol. 1994;196:263–281. doi: 10.1242/jeb.196.1.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Chan J. Ultrastructural localization of the serotonin transporter in limbic and motor compartments of the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7356–7366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07356.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quin Y, Melikian HE, Rye DB, Levey AI, Blakely RD. Identification and characterization of antidepressant-sensitive serotonin transporter proteins using site-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1261–1274. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01261.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:13–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry A, Mouillet-Richard S, Schneider B, Launay JM, Kellermann O. miR-16 targets the serotonin transporter: a new facet for adaptive responses to antidepressants. Science. 2010;329:1537–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1193692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmansour S, Cecchi M, Morilak DA, Gerhardt GA, Javors MA, Gould GG, et al. Effects of chronic antidepressant treatments on serotonin transporter function, density, and mRNA level. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10494–10501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10494.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmansour S, Owens WA, Cecchi M, Morilak DA, Frazer A. Serotonin clearance in vivo is altered to a greater extent by antidepressant-induced downregulation of the serotonin transporter than by acute blockade of this transporter. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6766–6772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06766.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau T, Horschitz S, Berger S, Bartsch D, Schloss P. Antidepressant-induced internalization of the serotonin transporter in serotonergic neurons. FASEB J. 2008;22:1702–1714. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-095471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeyro G, Blier P, Dennis T, de Montigny C. Desensitization of the neuronal 5-HT carrier following its long-term blockade. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3036–3047. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03036.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artigas F, Celada P, Laruelle M, Adell A. How does pindolol improve antidepressant action. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01682-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P, de Montigny C. Current advances and trends in the treatment of depression. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:220–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolozzi A, Castañé A, Semakova J, Santana N, Alvarado G, Cortés R, et al. Selective siRNA-mediated suppression of 5-HT1A autoreceptors evokes strong anti-depressant-like effects. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:612–623. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer A, Benmansour S. Delayed pharmacological effects of antidepressants. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:S23–S28. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Zhang HT, Bootzin E, Millan MJ, O'Donnel JM. Association of changes in norepinephrine and serotonin transporter expression with the long-term behavioral effects of antidepressant drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1467–1481. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguelova M, Benkelfat C, Turecki G. A systematic review of association studies investigating genes coding for serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter: II. Suicidal behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:646–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD, et al. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:815–826. doi: 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DL, Lesch KP. Targeting the murine serotonin transporter: insights into human neurobiology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeraldi E, Zanardi R, Benedetti F, Di Bella D, Perez J, Catalano M. Polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene and antidepressant efficacy of fluvoxamine. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:508–511. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanardi R, Serretti A, Rossini D, Franchini L, Cusin C, Lattuada E, et al. Factors affecting fluvoxamine antidepressant activity: influence of pindolol and 5-HTTLPR in delusional and nondelusional depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Yang RJ, Murphy DL, Crawley JN. Evaluation of antidepressant-related behavioral responses in mice lacking the serotonin transporter. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:914–923. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira A, Zhou M, Castanon N, Ansorge MS, Gordon JA, Francis JH, et al. Altered depression-related behaviors and functional changes in the dorsal raphe nucleus of serotonin transporter-deficient mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:960–971. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge MS, Zhou M, Lira A, Hen R, Gingrich JA. Early-life blockade of the 5-HT transporter alters emotional behavior in adult mice. Science. 2004;306:879–881. doi: 10.1126/science.1101678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Murphy DL, Crawley JN. Abnormal behavioral phenotypes of serotonin transporter knockout mice: parallels with human anxiety and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JE, Zupan B, Gross S, Toth M. Paradoxical anxiogenic response of juvenile mice to fluoxetine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2197–2207. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson BL, Boudreau RL. RNA interference: a tool for querying nervous system function and an emerging therapy. Neuron. 2007;53:781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakker DR, Natt F, Hüsken D, van der Putten H, Maier R, Hoyer D, et al. siRNA-mediated knockdown of the serotonin transporter in the adult mouse brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:782–789. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press: New York, USA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert C, Habimana A, Elie R, Reader TA. Effects of chronic antidepressant treatments on 5-HT and NA transporters in rat brain: an autoradiographic study. Neurochem Int. 2001;38:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro ME, Díaz A, Del Olmo E, Pazos A. Chronic fluoxetine induces opposite changes in G-protein coupling at pre and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors in rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2003;4:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amargós-Bosch M, Bortolozzi A, Puig MV, Serrats J, Adell A, Celada P, et al. Co-expression and in vivo interaction of serotonin1A and serotonin2A receptors in pyramidal neurons of prefrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14:281–299. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrés-Coy A, Santana N, Castañé A, Cortés R, Carmona MC, Toth M, et al. Acute 5-HT1A autoreceptor knockdown increases antidepressant responses and serotonin release in stressful conditions Psychopharmacology (Berl)advance online publication, 21 July 2012 (e-pub ahead of print); PMID:22820867. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Azmitia EC, Segal M. An autoradiographic analysis of the differential ascending projections of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1978;179:641–667. doi: 10.1002/cne.901790311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Mombereau C, Vassout A. The tail suspension test as a model for assessing antidepressant activity: review of pharmacological and genetic studies in mice. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:571–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Gould E, Manji H, Buncan M, Duman RS, Greshenfeld HK, et al. Preclinical models: status of basic research in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:503–528. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K, Kimura R, Sugimoto Y, Yamada J, Uchida S, Kato Y, et al. Relationship between brain serotonin transporter binding, plasma concentration and behavioural effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:695–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy S, Blakely RD. Phosphorylation and sequestration of serotonin transporters differentially modulated by psychostimulants. Science. 1999;285:763–766. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuvel DJ, Jayanthi LD, Bhat NR, Ramamoorthy S. A role of for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the regulation of the serotonin transporter: evidence for distinct cellular mechanisms involved in transporter surface expression. J Neurosci. 2005;25:29–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3754-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artigas F, Romero L, de Montigny C, Blier P. Acceleration of the effect of selected antidepressant drugs in major depression by 5-HT1A antagonists. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:378–383. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensler JG. Differential regulation of 5-HT1A receptor-G protein interactions in brain following chronic antidepressant administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:565–573. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arborelius L, Hawks BW, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB. Increased responsiveness of presumed 5-HT cells to citalopram in adult rats subjected to prolonged maternal separation relative to brief separation. Psychopharmacology. 2004;176:248–255. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Artigas F. Preferential potentiation of the effects of serotonin uptake inhibitors by 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the dorsal raphe pathway: role of somatodendritic autoreceptors. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2593–2603. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeyro G, Blier P. Autoregulation of serotonin neurons: role in antidepressant drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:91S–98S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuade R, Sharp T. Functional mapping of dorsal and median raphe 5-hydroxytryptamine pathways in forebrain of the rat using microdialysis. J Neurochem. 1997;69:791–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69020791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee N, Sivalingam S, Boonstra R, Wojtowicz JM. The utility of Ki-67 and BrdU as proliferative markers of adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias BG, Banerjee SB, Duman RS, Vaidya VA. Differential regulation of brain derived neurotrophic factor transcripts by antidepressant treatments in the adult rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS. Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7539–7547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman RS. VEGF is an essential mediator of the neurogenic and behavioral actions of antidepressants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4647–4652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610282104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant administration increases the expression of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2365–2372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02365.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Q, Zetterström TS, Sprakes M, Tordera R, Sharp T. Antidepressant drug treatment induces Arc gene expression in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 2003;121:975–982. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DT, Bysmaster FP, Reid LR, Fuller RW, Perry KW. Inhibition of serotonin uptake by optical isomers of fluoxetine. Drug Dev Res. 1985;6:397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel H, Vicentic A, Kuhar MJ. Neurotransmitter transporters synthesis and degradation rates. Life Sci. 2001;68:2181–2185. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, et al. Requirement of.hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HD, Duman RS. The role of neurotrophic factors in adult hippocampal neurogenesis, antidepressant treatments and animal models of depressive-like behavior. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:391–418. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282ee2aa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker TL, White A, Black DM, Wallace RH, Sah P, Bartlett PF. Latent stem and progenitor cells in the hippocampus are activated by neural excitation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5240–5247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0344-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.