Abstract

Objectives

Interactions between breast cancer patients and their oncologists are important as effective patient-physician communication can facilitate the delivery of quality cancer care. However, little is known about patient-physician communication processes among Asian American breast cancer patients, who may have unique communication needs and challenges. Thus, we interviewed Asian American patients and several oncologists to explore patient-physician communication processes in breast cancer care.

Methods

We conducted in-depth interviews with nine Chinese- or Korean American breast cancer patients and three Asian American oncologists who routinely provided care for Asian American patients in the Washington DC metropolitan area in 2010. We conducted patient interviews in Chinese or Korean and then translated into English. We conducted physicians’ interviews in English. We performed qualitative analyses to identify themes.

Results

For women with limited English proficiency, language was the greatest barrier to understanding information and making treatment-related decisions. Both patients and oncologists believed that interpretation provided by patients’ family members may not be accurate, and patients may neglect to ask questions because of their worry of burdening others. We observed cultural differences regarding expectations of the doctor’s role and views of cancer recovery. As expressed by the patients and observed by oncologists, Asian American women are less likely to be assertive and are mostly reliant on physicians to make treatment decisions. However, many patients expressed a desire to be actively involved in the decision-making process.

Conclusion

Findings provide preliminary insight into patient-physician communication and identify several aspects of patient-physician communication that need to be improved for Asian American breast cancer patients. Proper patient education with linguistically and culturally appropriate information and tools may help improve communication and decision-making processes for Asian American women with breast cancer.

Keywords: Asian American, breast cancer, patient-physician communication, language barrier, cultural difference, treatment decision making

Introduction

Effective patient-physician communication has been stressed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) as a crucial aspect of providing quality cancer care. According to the IOM, in an effective patient-physician communication process, patients should be able to understand the information they receive as well as express their needs and preferences to their health care providers [1]. Breast cancer care is very complex involving a wide range of treatment options and coordination of multiple health care providers both during cancer treatment and long-term survivorship care. Therefore, effective communication between cancer patients and their health care providers is an extremely important element of such care [2]. A growing body of literature has suggested that a positive communication experience with the health care team is associated with greater satisfaction with care [3–5], greater psychological adjustment [6], reduced anxiety and depression [5,7], and higher quality of life [4,8] among cancer patients. Others reported patient-physician communication as being key to the establishment of a trusting and respectful patient-physician relationship and patient-centered care [9–11]. Despite its importance, only a few studies have directly examined the communication experience among minority women with breast cancer. These studies revealed that minority women ask fewer questions during medical visits compared to non-minority women [12] and desire to be cared for as a whole human being, receive personal attention, and to have a collaborative role in treatment decision making [13,14]. To our knowledge, only one previous study (published in two papers) has documented Asian American breast cancer patients’ perceptions of their interaction with physicians, in which themes such as following doctor’s recommendations, dependence on the doctor in making treatment decisions and need for proper advice on diet and physical activity were identified [15,16].

In light of the rapid increase in breast cancer incidence among Asian American women [17] combined with the scarcity of research on patient-physician communication in this patient subgroup, the current study describes the communication needs and challenges of Chinese and Korean American women with breast cancer using in-depth interviews with patients and oncologists. As perspectives from physicians have been rarely reported [18], this study will contribute to the literature by comparing and contrasting the perceptions of the two parties in this communication process.

Methods

Study design

Two interviewers bilingual in English and Chinese or Korean conducted in-depth interviews. They were trained in interviewing techniques and then conducted in-depth interviews with nine breast cancer patients and three oncologists that provided care for Asian American breast cancer patients.

Recruitment of Study Participants

We identified a convenience sample of nine Chinese and Korean American breast cancer patients through community-based organizations located in the Washington DC metropolitan area, postings on websites well known to Chinese or Korean immigrants, and personal contacts. We recruited three oncologists who routinely treat Asian American breast cancer patients through personal contacts. Given the exploratory nature of this pilot study, a diverse sample was sought with respect to patient age, education levels, survivorship (e.g., length of time since diagnosis), and treatment options (e.g., surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or any combination of these). The oncologists and patients were not matched in that the oncologists did not necessarily provide care for the patients who were interviewed.

Data collection

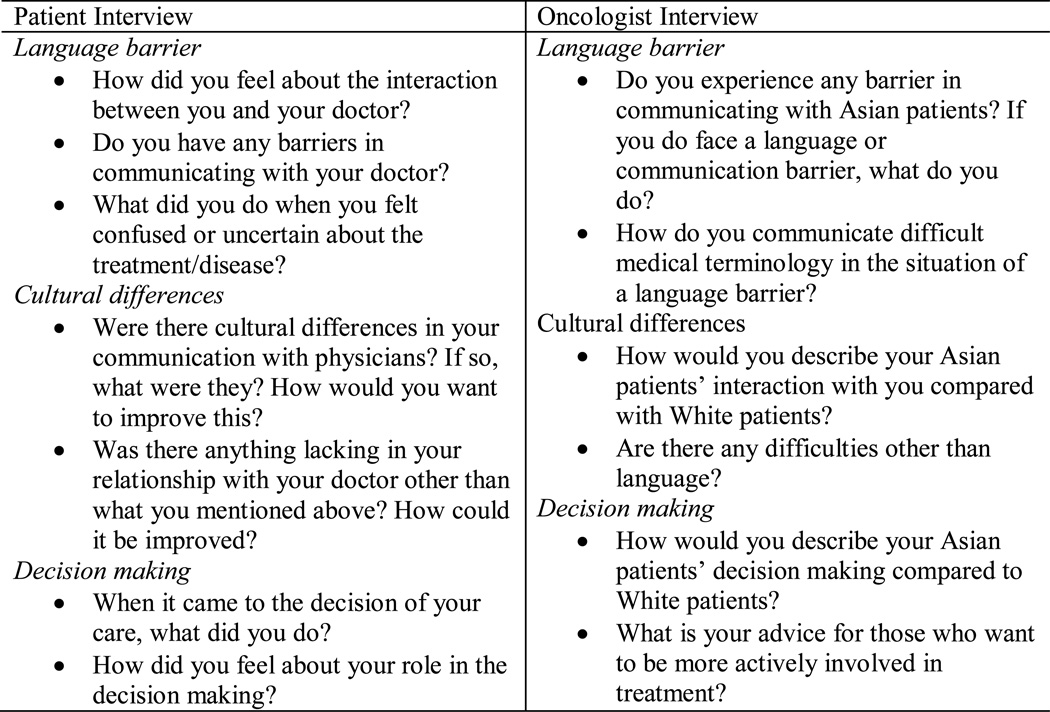

We developed separate interview guides for patients and oncologists based on findings from the existing literature and guidance from experts on breast cancer survivorship. A list of key interview questions is presented in Figure 1. We interviewed each participant individually in Chinese or Korean, and interviews lasted approximately two hours. We also interviewed oncologists individually in English. Each interview lasted about 45 minutes. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of University of Maryland, College Park. We obtained informed consent from all participants prior to the interviews, and tape-recorded interviews with permission from the participants.

Figure 1.

Core interview questions

Data analysis

We transcribed all interviews verbatim and then translated into English. The research team reviewed transcripts and created a codebook to guide the coding process. We identified main categories (e.g., language barrier, cultural differences) and subthemes under each category (e.g., interpretation by family members and medical interpreter under language barriers). With the codebook serving as a general framework, the coders were allowed to create new categories or subthemes when necessary. Two independent coders qualitatively analyzed each transcript simultaneously. The results were then contrasted and compared to assure accuracy and completeness using MAX QDA, a qualitative analysis software.

Results

Patient Characteristics

We interviewed four Chinese and five Korean breast cancer patients. On average, patients were 54 years old. All but one participant was diagnosed with breast cancer within the past 5 years. The majority of them had early stage breast cancer (stage 1 to 3). As stated in our aim in the recruitment for a diverse sample, our participants varied in characteristics such as education (from high school to graduate school), annual household income (from less than $20,000 to more than $100,000) and acculturation status (e.g., years of living in the U.S. ranging from 7 to 35 years). Although seven out of nine participants responded as speaking English well or fluently, we found a strong theme of having a ‘language barrier’ in their communication with oncologists. This incongruity may indicate that subjectively assessed fluency in everyday conversation may not be sufficient in the medical setting when conversing about cancer diagnosis and treatment. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Patients Socio-demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at interview (yrs) (mean, range) | 53.7 (44–66) |

| Time since diagnosis (yrs) (mean, SE)a | 1.9 (1–5) |

| Stage of Breast Cancer | |

| 1 | 2 (22.2%) |

| 2 | 5 (55.6%) |

| 3 | 1 (11.1%) |

| 4 | 1 (11.1%) |

| Treatment Status | |

| Ongoing | 1 (11.1%) |

| Completed | 8 (88.9%) |

| Highest Schooling Completed | |

| High school or less | 2 (22.2%) |

| Some college | 0 |

| College graduate or above | 7 (77.8%) |

| Annual household income | |

| <$20,000 | 1 (11.1%) |

| $20,000–49,999 | 2 (22.2%) |

| $50,000–74,999 | 0 |

| $75,000–99,999 | 4 (44.4%) |

| >$100,000 | 2 (22.2%) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 6 (66.7%) |

| Unemployed | 1 (11.1%) |

| Retired | 1 (11.1%) |

| Housewife | 1 (11.1%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 7 (77.8%) |

| Divorced | 1 (11.1%) |

| Never been married | 1 (11.1%) |

| Years lived in US (yrs) (mean, SE) | 18.6 (10.5) |

| Speaking English | |

| Not at all | 1 (11.1%) |

| Not well | 1 (11.1%) |

| Well | 5 (55.6%) |

| Fluently | 2 (22.2%) |

| Reading English | |

| Not at all | 1 (11.1%) |

| Not well | 1 (11.1%) |

| Well | 6 (66.7%) |

| Fluently | 1 (11.1%) |

| Language spoken at home | |

| English | 3 (33.3%) |

| Korean or Chinese | 5 (55.6%) |

| English and Korean/Chinese equally | 1 (11.1%) |

| Perception of identity | |

| Very Asian | 5 (55.6%) |

| Mostly Asian | 0 |

| Bicultural | 2 (22.2%) |

| Mostly Westernized | 2 (22.2%) |

| Very Westernized | 0 |

| Years of school in US (mean, range) | 2.1 (0–8) |

One Korean patient who was diagnosed 21 years ago was excluded from calculating the average because all others were diagnosed within 5 years.

Oncologists Characteristics

Among the three oncologists we interviewed, two were female. They were 46, 49, and 36 years old respectively. One was born in Korea, one was born in India and the other was born in the U.S. All of them were medical oncologists, working in private practice, and spoke at least one language other than English (e.g., Korean, Spanish, Tamil). On average, they had been practicing medicine for 19 years (ranging from 14–22 years), and they saw 20–40 Asian American patients per year.

Across both patient and oncologist interviews, three major categories emerged: Language barriers, cultural differences, and treatment decision making.

Language barriers

Difficulties in understanding and speaking English were the most common barriers to communicating with doctors. Using family members or friends as interpreters was common among Asian breast cancer patients according to the oncologists. They expressed concerns regarding the quality of interpretation provided by these lay persons who were not trained as medical interpreters and may not convey the information accurately. Even with a medical interpreter, oncologists were still concerned that the explanation may not be sufficiently described for patients to understand what they were told.

“The interpreter cannot be depended upon a lot of times because they may not explain every word by word.” (A female oncologist)

Even worse, when there was no interpreter (e.g., in a radiation therapy room where the patients had to be left alone), participants said they “just didn’t know what he (the doctor) was talking about”, relied on body language (e.g., pointing at the body part where they felt pain), used simple words (e.g. “little bad” “not bad”), or guessed the meaning of what was being said by the doctor.

The oncologists’ concern that some Asian breast cancer patients, who did not speak English, might neglect to ask questions was confirmed by our participants. One patient who used interpretation services provided by the clinic wondered why she was told to have chemotherapy prior to the surgery. Even though she “wanted to ask”, she “could not speak it” and “did not ask him (the doctor) at last”. According to the oncologists, some Asian patients may also be concerned about the burden placed on the family member accompanying them to the medical visits, and therefore avoid asking questions in order to shorten the appointment.

Medical terminology was a challenge even for participants who reported speaking fluent English.

“Because they (health professionals) were using medical terminologies, it was hard to understand. And because of lack of knowledge about the cancer and its symptoms, it was very difficult to understand even if I went there and listened to doctors with my husband.” (A 46-year old Korean woman)

Some patients described strategies that they used to help them with their language barriers such as bringing native English speakers with them to the doctor’s office and preparing a diary of symptoms in English to show the doctor. They thought these were very helpful in improving her communication with the physician.

Cultural differences

Although most patients did not perceive cultural differences to be a significant barrier in communicating with physicians, there were discrepancies between their expectations and the actual care they received. For instance, a 55-year old Chinese woman stated that she presented her numerous side effects from chemotherapy to the doctor but was frustrated by the physician’s response of “What do you expect me to do”. She expected the doctor to provide her with answers rather than questions.

Although oncologists held similar perceptions regarding Asian patients’ expectation of physicians being the experts, one of the oncologists thought that too much information may scare away some of these patients. “Some people just cannot take all information, they get confused, and they might go to a different physician that will just tell them this is what you need to do to get well. Sometimes that’s just better for them” (a male oncologist).

Cultural differences were also evident regarding the provision of information on diet and physical activity. Some patients thought physicians’ diet recommendations were too general and suggestions for physical activity were too difficult to follow.

“If you went to ask American doctors and nurses about the diet, they would tell you that you could eat everything you wanted. But after reading materials, I learned that actually there are certain things that you should not eat.” (A 55-year old Chinese woman)

Oncologists agreed that some Asian breast cancer patients want to know very specifically what they can or cannot eat and that patients were surprised when told to just eat a healthy balanced diet.

Treatment decision making

Physicians played a leading role in making treatment decisions in most patients’ cases regardless of education level or English speaking ability. Some patients had no other choice but to follow the doctor when making decisions because they “had no one to ask questions and had no time to collect the related information about how to deal with cancer” (A 55-year old Chinese woman). Oncologists also pointed out that some Asian patients had difficulty in seeking treatment information from channels other than physicians due to language barriers.

“I feel terrible for some of these women who have to make decisions without understanding the language, not being able to read about it. They just sort of blindly subjecting themselves to these procedures.” (A female oncologist).

The preferred level of involvement in decision making varied across individuals. Reported by both oncologists and patients, some Asian patients were comfortable and content with “following the doctor’s order”. A 66-year old Chinese woman emphasized that patients should follow their doctors because “they (doctors) had good research and good analysis”. Even for those who thought of themselves as being actively involved in the treatment decision making, patients admitted that they kept in accordance with the doctor’s suggestions most of the time.

The influence from family members was more evident in participants who had limited English proficiency. A 66-year old Chinese woman relied on her son, who worked in a medically-related field, to communicate with the doctor and to make treatment decisions. Despite the dominant power of physicians and influence from family, many patients expressed their desire to be actively involved in the decision making. Some of them described how they participated in the process.

“When I had to choose the treatment, she (the oncologist) asked me first if I wanted to choose it. I didn’t want to have radiation therapy so I refused it. The oncologist and other doctors discussed it many times based on my opinion. Thankfully, they respected my decision and did their best to help me.” (A 61-year old Korean woman)

Patients whose participation in decision making was limited due to English ability also treasured active involvement in decision making. The woman who depended on her son to translate and make decisions also stated the importance of patients’ involvement and agreement to the decision, otherwise she would be “forced to follow family’s wish, which is really uncomfortable”.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies in literature to employ a qualitative approach to investigate the communication experience of Asian American breast cancer patients from the perspectives of the patients and oncologists. Results provide preliminary insight into the communication experience of Asian American breast cancer patients and inform the development of culturally appropriate programs that aim to improve patient-physician communication.

Having a language barrier was identified as the most significant obstacle in patient-physician communication by both Asian American breast cancer patients and oncologists. Reliance on family members or friends for interpretation was a common strategy, but it may problematic due to potential inaccuracy of interpretation and patients’ concerns with burdening others. Using a medical interpreter was reported by one of the patients, but she still experienced difficulty in understanding medical information and could not voluntarily ask questions due to low health literacy.

Patients also reported using other strategies to overcome language difficulties, such as taking notes and bringing a native English speaker to medical visits. However, neither the patients nor the oncologists mentioned any efforts by physicians for improving the communication process. A survey with 301 oncologists and surgeons found that among those who saw patients with limited English ability, more than half reported difficulty in patient-physician communication and acknowledged to have less patient-centered treatment discussion with these patients [19]. On the other hand, having sufficient information regarding their illness and treatment was highly desired by breast cancer patients and regarded as a way to gain power and control over their illness and future lives [20]. In order to achieve effective communication, both physicians and patients should engage in behaviors that are intended for this purpose. For example, physicians should provide clear and jargon-free explanations and encourage patients to express their beliefs and preferences, while patients should be assertive in asking questions and verbalizing their concerns [21]. For Asian American breast cancer patients, our findings suggest that physicians need to provide sufficient information in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.

In general, patients and oncologists did not perceive cultural differences as hindering the communication process during medical visits. Nevertheless, our results suggest that discrepancies exist between patients’ expectations and the doctors’ manner of giving advice. Some Asian patients expect the physician to be an expert and give more direct advice. This was the case with diet and physical activity where there is a need for more culturally appropriate information from doctors. Asian breast cancer patients’ dissatisfaction with physician recommendations on diet and physical activity has been reported previously [15]. Complaints included lack of specific guidance on diet and recommendations on physical activity being too demanding. Among many Asian breast cancer patients, diet is perceived to be a key contributor to an individual’s health, including cancer and its recurrence [15, 22]. Though oncologists in our study encountered such cultural difference regarding beliefs in diet, they did not seem to have developed any strategies for responding to such needs. Understanding and validating patients’ concerns and beliefs is essential for effective communication in patient-centered care [21]. It is important that physicians who care for Asian American breast cancer patients recognize the cultural beliefs of these women and tailor the information to such needs.

As reported by both patients and oncologists, Asian American breast cancer patients tend to follow their doctors’ advice in treatment decisions. Family members may also influence treatment decisions for elderly women, especially when the patients cannot speak English. Such strong reliance on doctors and family members to make treatment decisions may be due, in part, to low health literacy and a lack of adequate information available in a language that women can understand. Latina breast cancer patients, who had limited English ability, were found to be more likely than their White and African American counterparts to report dissatisfaction and regret with their treatment decisions. Low health literacy was suspected to play a role in that association [23]. The leading role of doctors in treatment decision making may be explained by Asian American breast cancer patients’ perception of physicians having authority and power and patients’ confidence in physicians’ medical knowledge and ability. Tam Ashing et al. reported similar observations from a focus group study with Asian breast cancer patients in California. Nevertheless, most women we interviewed expressed the desire to play an active role in decision making and some of them had taken measures to do so. While encouragement for active involvement in treatment decision is certainly needed for Asian American breast cancer patients, it is also important to acknowledge that preferences for the level of patient involvement in decision making may vary by individual [24].

Our study provides unique insights into patient-physician communication from the perspectives of Asian American breast cancer patients and oncologists. However, caution is needed when interpreting the findings. First, the patients and oncologists included in our study were not matched, which limits us from directly contrasting the perceptions and experiences from patients and oncologists. Second, most women in our study were recently diagnosed patients with early stage breast cancer. Thus, our findings may not be generalizeable to breast cancer patients with different disease characteristics. Third, this study includes a convenience sample of nine patients and three oncologists. Therefore, they are not representative of either group. Lastly, only two groups of Asian American women (Chinese and Korean American women) are included in the study, and therefore, results may not be generalizable to all Asian American groups.

Our study also identified several aspects of patient-physician communication that need to be improved. Efforts should be made to develop a culturally appropriate patient education program for Asian American breast cancer patients to teach strategies and skills to communicate effectively with physicians in the context of their cultural background. Specifically, all these education will be delivered in linguistically appropriate manner and cultural differences in patient-physician communication (such as asking many questions is fine in American culture vs. follow orders of doctor because he or she is an authority figure in Asian culture) will be explained. Teaching patients how to prepare for a doctor’s visit (such as preparing a list of questions) and what patients can expect to receive (such as a treatment summary or follow-up care plan) will be another component of education program. As for the physicians, we suggest an educational program that helps them understand patient needs, or helps them develop skills to probe for patient understanding. We suggest developing a program (embedded in the healthcare system) where if a doctor identifies a patient as needing more time to understand the information, the patient can then be referred to another healthcare professional (such as a nurse or community health educator) who can take the time to explain everything in detail.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by National Institute of Health-National Cancer Institute’s Community Network Program Center, ACCHDC U54 CNPA (1U54CA 153513-01, PI: Grace X. Ma).

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041, Maryland Population Research Center.

We appreciate contribution from research assistants Youngsuk Oh and Lynn Scully in data collection.

References

- 1.Adler NE, Page A National Institue of Medicine (U.S.) Cancer care for the whole patient : meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2008. Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients / Families in a Community Setting. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt ME, Herdman R, Holland JC, et al. Meeting psychosocial needs of women with breast cancer. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez LS, Schwartz JS, Freres D, et al. Patient-clinician information engagement increases treatment decision satisfaction among cancer patients through feeling of being informed. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 Dec;77(3):384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB, et al. Doctor-patient communication and cancer patients' quality of life and satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000 Sep;41(2):145–156. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel BA, Leonhart R, Helmes AW. Communication matters: the impact of communication and participation in decision making on breast cancer patients' depression and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 Dec;77(3):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts CS, Cox CE, Reintgen DS, et al. Influence of physician communication on newly diagnosed breast patients' psychologic adjustment and decision-making. Cancer. 1994 Jul 1;74(1 Suppl):336–341. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820741319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallowfield LJ, Hall A, Maguire GP, et al. Psychological outcomes of different treatment policies in women with early breast cancer outside a clinical trial. Bmj. 1990 Sep 22;301(6752):575–580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6752.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Street RL, Jr, Voigt B. Patient participation in deciding breast cancer treatment and subsequent quality of life. Med Decis Making. 1997 Jul-Sep;17(3):298–306. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9701700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayton MF, Dudley WN. Patient-centered communication during oncology follow-up visits for breast cancer survivors: content and temporal structure. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009 Mar;36(2):E68–E79. doi: 10.1188/09.onf.e68-e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McWilliam CL, Brown JB, Stewart M. Breast cancer patients' experiences of patient-doctor communication: a working relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000 Feb;39(20–3):191–204. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright EB, Holcombe C, Salmon P. Doctors' communication of trust, care, and respect in breast cancer: qualitative study. Bmj. 2004 Apr 10;328(7444):864. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38046.771308.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH. Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Sep;62(3):355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davey MP, Kissil K, Nino A, et al. "They paid no mind to my state of mind": African American breast cancer patients' experiences of cancer care delivery. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010 Nov;28(6):683–698. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2010.516807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royak-Schaler R, Passmore SR, Gadalla S, et al. Exploring patient-physician communication in breast cancer care for African American women following primary treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008 Sep;35(5):836–843. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.836-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tam Ashing K, Padilla G, Tejero J, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psychooncology. 2003 Jan-Feb;12(1):38–58. doi: 10.1002/pon.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004 Jun;13(6):408–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez SL, Quach T, Horn-Ross PL, et al. Hidden breast cancer disparities in Asian women: disaggregating incidence rates by ethnicity and migrant status. Am J Public Health. 2010 Apr 1;100(Suppl 1):S125–S131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clayman ML, Boberg EW, Makoul G. The use of patient and provider perspectives to develop a patient-oriented website for women diagnosed with breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008 Sep;72(3):429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karliner LS, Hwang ES, Nickleach D, et al. Language barriers and patient-centered breast cancer care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 Aug;84(2):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakker DA, Fitch MI, Gray R, et al. Patient-health care provider communication during chemotherapy treatment: the perspectives of women with breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2001 Apr;43(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein RM, Street RLJ. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson PB. Family beliefs about diet and traditional Chinese medicine for Hong Kong women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003 Sep-Oct;30(5):834–840. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.834-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawley ST, Janz NK, Hamilton A, et al. Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008 Nov;73(2):363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polacek GN, Ramos MC, Ferrer RL. Breast cancer disparities and decision-making among U.S. women. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 Feb;65(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]