Summary

The application of stem cells to regenerative medicine depends on a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying their pluripotency. Many studies have identified key transcription factor-regulated transcriptional networks and chromatin landscapes of embryonic and a number of adult stem cells. In addition, recent publications have revealed another interesting molecular feature of stem cells— a distinct alternative splicing pattern. Thus, it is possible that both the identity and activity of stem cells are maintained by stem cell-specific mRNA isoforms, while switching to different isoforms ensures proper differentiation. In this review, we will discuss the generality of mRNA isoform switching and its interaction with other molecular mechanisms to regulate stem cell pluripotency, as well as the reprogramming process in which differentiated cells are induced to become pluripotent stem cell-like cells (iPSCs).

Keywords: alternative splicing, embryonic stem cells, adult stem cells, stem cell maintenance and differentiation, post-transcriptional regulation, epigenetic regulation

Introduction

Stem cells are unique in that they both self-renew and give rise to a variety of differentiated cell types. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are isolated from the inner cell mass of mammalian blastocysts and propagated in culturing systems (Evans and Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981). ESCs can be induced to differentiate into distinct cell types and therefore hold the promise for therapeutic applications (Smith, 2001). More excitingly, in both mouse and human, differentiated somatic cells can be reprogrammed to become ESC-like iPSCs (Park et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2007; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al., 2007). Moreover, mouse male germ cells have been shown to retain the potential to become ESC-like cells in vitro and in vivo (Guan et al., 2006; Kanatsu-Shinohara et al., 2004). These exciting discoveries, which involve the reversal of lineage commitment for both somatic and germ cells, open an entirely new avenue for applying stem cells in regenerative medicine.

Another type of stem cell is the naturally existing adult stem cells, which are required for tissue homeostasis and regeneration in adulthood (Losick et al., 2011; Morrison and Spradling, 2008). The adult stem cell normally divides asymmetrically, either as a single cell or as a group of cells, to self-renew and give rise to daughter cells that initiate differentiation (Yamashita et al., 2010). Before turning on the terminal differentiation program, progenitor cells derived from stem cells normally undergo proliferation to expand their population for high-throughput yield of terminally differentiated cell types. Such activities of stem cells need to be tightly controlled. Imbalances that arise between stem cell self-renewal versus differentiation, or between progenitor cell proliferation versus differentiation, are common causes of many human diseases, including cancers, tissue dystrophy and infertility (Morrison and Kimble, 2006; Rossi et al., 2008).

To effectively use stem cells in regenerative medicine, the molecular mechanisms underlying stem cell maintenance, proper differentiation, and reprogramming need to be thoroughly understood. Particularly, the stem cell transcriptome needs to be resolved at the levels of both transcript abundance and isoform structure. In addition, transcriptional network and chromatin landscape need to be delineated to understand the regulatory circuitries that maintain stem cell pluripotency and prevent precocious differentiation. Indeed, recent years have witnessed substantial progress in these areas (Chen, 2008).

Recently, new technologies, including exon tiling arrays and high-throughput mRNA sequencing (RNA-seq), have revolutionized our understanding of transcription and alternative splicing (AS) in various stem cell lineages, including ESCs and adult stem cells in different organisms. In particular, several new studies have revealed that differential gene expression in stem cell lineages involves mRNA isoform switching from stem cells to differentiated cells, ranging from ESCs to various adult stem cells, and across the animal kingdom from Drosophila to humans (Gabut et al., 2011; Gan et al., 2010; Pritsker et al., 2005; Salomonis et al., 2009; Salomonis et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2010; Yeo et al., 2007). This switching either leads to changes in particular coding sequences, which may affect protein structure and/or subcellular localization, or it results in changes at the non-coding sequences, which may alter post-transcriptional regulation, such as microRNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) (Barash et al., 2010; Lareau et al., 2007; Ni et al., 2007). In this review, we discuss these recent results and hypothesize that mRNA isoform switching may serve as a common molecular mechanism that acts cooperatively with other epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone modifications, in regulating stem cell function.

Alternative splicing in the regulation of ESC pluripotency and lineage-specific differentiation

Molecular mechanisms underlying the pluripotency of ESCs have been extensively investigated, but most studies have focused on dissecting the key transcription factor-regulated transcriptional network (Boyer et al., 2005; Boyer et al., 2006a; Loh et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2007) and chromatin structure (Azuara et al., 2006; Bernstein et al., 2006; Boyer et al., 2006b; Guenther et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2006b; Mikkelsen et al., 2007; Stock et al., 2007). However, recent studies using new technologies, including RNA-seq, have shown the importance of ESC-specific mRNA isoforms (Das et al., 2011; Kunarso et al., 2008), as well as changes of isoforms during ESC differentiation (Gabut et al., 2011; Pritsker et al., 2005; Salomonis et al., 2009; Salomonis et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2010; Yeo et al., 2007).

Interestingly, several studies have demonstrated high diversity of isoforms in stem cells, but low diversity of isoforms in differentiated cells, a phenomenon called “isoform specialization” (Wu et al., 2010). To account for this, it is speculated that stem cells may require a high diversity of isoforms to maintain their identities, while reduction into specific isoforms in differentiating cells may ensure proper differentiation. The diverse isoforms co-expressed in stem cells have non-redundant functions. For example, a pluripotency transcription factor, Sal-like protein 4 (Sall4), has two isoforms, Sall4a (long isoform) and Sall4b (short isoform), in mouse ESCs (Rao et al., 2010). Although both Sall4a and Sall4b interact with one of the core transcription factors Nanog in ESCs (Wu et al., 2006), they have distinct roles. Specifically, Sall4a represses expression of differentiation genes, while Sall4b essentially maintains high expression of pluripotency genes. This phenomenon whereby a critical transcription factor sustains multiple isoforms in ESCs also applies to the Wnt-responsive transcription factor TCF3. Here, again, both TCF3(l) (long isoform) and TCF3(s) (short isoform) are co-expressed in ESCs and regulate expression of different sets of target genes (Salomonis et al., 2010). Other examples include critical cell cycle regulators, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway components MAP4K2 and MNK1 kinases, which also have different isoforms in stem cells (Pritsker et al., 2005). In these examples, it is possible that coordinated activities of proteins encoded by different isoforms are required for maintaining ESC pluripotency.

In other cases, changes in alternative splicing during ESC differentiation are accompanied by isoform switching, in which stem cells and differentiated cells have distinct isoforms. Isoform switching is probably required for lineage specification during ESC differentiation. An earlier study using the EST (expressed sequence tag) library showed that genes required for lineage-specific differentiation undergo AS at a higher frequency than housekeeping genes (Pritsker et al., 2005). Recent RNA-seq data obtained from distinct human organs have also revealed abundant isoform switching for tissue-specific genes (Wang et al., 2008).

Isoform switching during ESC differentiation has been shown to mainly affect coding sequences, resulting in protein domain truncation, disruption, exchange, or modification (Salomonis et al., 2010). Interestingly, many of the genes that show this isoform switching phenomenon encode critical regulators. For example, the master transcription factor OCT4 that regulates ESC self-renewal has an ESC-specific isoform (OCT4A). Upon differentiation, OCT4A expression is greatly reduced, while two other isoforms, OCT4B and OCT4B1, take over (Atlasi et al., 2008). It has been shown that OCT4B has distinct subcellular localization and DNA binding affinity different from OCT4A (Lee et al., 2006a), suggesting that OCT4B and OCT4A regulate different target genes in differentiating cells and stem cells, respectively. A recent study reveals that the Forkhead box (FOX) transcription factor FOXP1 has an ESC-specific isoform, which is different from the more broadly expressed isoform (Gabut et al., 2011). The particular switching of an exon in FOXP1 transcript results in amino acid changes within the critical forkhead DNA-binding domain, and this leads to different choices of target genes. In this case, the ESC-specific FOXP1 (FOXP1-ES) acts as a transcriptional activator for pluripotency genes, such as OCT4 and NANOG, while it acts as a transcriptional repressor for differentiation genes. Interestingly, this dual role of FOXP1-ES is also required for efficient reprogramming of somatic cells to iPSCs, suggesting a critical role for this isoform switching in maintaining, as well as restoring, ESC function. In other cases, switched mRNA isoforms even encode proteins with antagonistic functions. For example, fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4) acts as an important autocrine factor to maintain human ESC pluripotency, whereas its truncated isoform encoded by FGF4si antagonizes FGF4 function and promotes differentiation (Mayshar et al., 2008). Genome-wide analysis reveals different AS patterns in different human tissues and cell lines (Sultan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Further functional studies in model organisms are needed to specifically knockdown or overexpress particular isoforms to determine the biological significance of these changes.

Isoform switching can also lead to changes at regulatory regions, such as 3′UTRs (Untranslated Regions). Different 3′UTRs may subsequently allow post-transcriptional regulation via distinct microRNAs. For instance, the Serca2 gene encodes a calcium pump essential for cardiac muscle cell function. Its protein expression is repressed by microRNAs in ESCs. However, during mouse ESC cardiac differentiation, a specific Serca2 isoform with shorter 3′UTR is produced through exon exclusion, which allows it to escape microRNA binding and repression (Salomonis et al., 2010). In addition to microRNAs, NMD adds another mechanism to regulate transcript abundance in stem cells and differentiated cells. For example, a particular set of premature termination codon-introducing exons are excluded in stem cells or embryonic tissues in order to maintain gene expression at a high level, whereas they are included in differentiated tissues to activate NMD and reduce expression level for the corresponding genes (Barash et al., 2010).

Alternative splicing in the regulation of adult stem cell maintenance and differentiation

Adult stem cells are multi-potent or uni-potent cells that exist under physiological conditions and function to maintain tissue homeostasis by replenishing short-lived cells, such as skin, muscle, intestinal, and blood cells, as well as sperm [reviewed in (Morrison and Spradling, 2008)]. Understanding the molecular characteristics of adult stem cells will greatly facilitate targeted differentiation of ESCs to lineage-committed adult stem cells, or the reprogramming of differentiated cells to adult stem cells. This could be followed by transplantation of adult stem cells to their physiological environments, thus serving as basis for curing genetic diseases and age-dependent tissue degeneration. Compared to ESCs, very little is known about how alternative splicing regulates adult stem cell maintenance and differentiation, partly because of their extremely small numbers in vivo, as well as technical difficulties associated with their isolation and purification [reviewed in (Eun et al., 2010)].

The Drosophila germline stem cells (GSCs) provide paradigmatic model systems to study adult stem cell identity and activity [reviewed in (Fuller and Spradling, 2007; Losick et al., 2011)]. During Drosophila male GSC differentiation, AS events are significantly more abundant in undifferentiated cell-enriched bag-of-marbles (bam) mutant testes than in wild-type testes which mainly contain differentiating cells (Gan et al., 2010). The infrequency of splicing events in differentiating germ cells is partly achieved by turning on a large set of single-isoform or intronless genes, which probably serves as a mechanism to ensure robust expression of nearly a thousand genes for terminal differentiation (Gan et al., 2010). However, isoform switching of multi-isoform genes is also detected at the transition from mitotic germ cells to meiotic germ cells [(Gan et al., 2010) and unpublished results]. Further analyses will be performed to address their functions in regulating spermatogenesis.

Hematopoiesis and myogenesis are two other well-characterized cellular differentiation processes that rely on the activities of adult stem cells. Genome-wide studies of the mammalian hematopoietic stem cell lineage reveal that lineage-specific genes and signaling pathway components have a higher propensity to undergo splicing than housekeeping genes, providing great opportunities for functional studies (Lemischka and Pritsker, 2006; Pritsker et al., 2005). For example, the transcription factor-encoding Ikaros (Ik) gene undergoes dynamic AS to produce various isoforms that restrict hematopoietic stem cells to differentiate along the lymphoid pathway. Distinct Ik isoforms differ in their protein-coding sequences, resulting in distinct subcellular localizations of Ik proteins responsible for their different transcription activation abilities (Molnar and Georgopoulos, 1994).

Using splicing-sensitive microarray (Bland et al., 2010) and RNA-seq (Trapnell et al., 2010) techniques, recent studies have also demonstrated robust splicing switching of several hundred genes during mammalian myoblast differentiation. Subsequent studies reveal that the majority of these genes switch isoforms in coordination with the myogenic differentiation program and might be temporally controlled. Moreover, the splicing switching during myogenesis occurs even before expression of myogenic transcription factors, suggesting that isoform switching may poise myoblast progenitor cells for myogenic differentiation (Bland et al., 2010). Finally, isoform changes for many genes, including the crucial Myc transcription factor, are so dynamic that they cannot be ascribed to a simple “pattern switching” (Trapnell et al., 2010). Therefore, more detailed analyses of individual genes are required to thoroughly understand how AS regulates muscle stem cell differentiation.

Regulation of isoform switching during stem cell differentiation by splicing factors

The regulation of AS pattern switching in stem cell lineages at the molecular level remains an open question. However, we do know that AS is regulated by RNA-protein complexes called spliceosomes, consisting of five small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs) and hundreds of protein components [reviewed in (Jurica and Moore, 2003; Wahl et al., 2009)]. The trans-acting RNA binding proteins (RBPs) act by directly recognizing and binding to splicing regulatory elements in pre-mRNAs, either as splicing enhancers or silencers, to determine inclusion or exclusion of a particular exon [reviewed in (Wang and Burge, 2008)]. Therefore, the ultimate choice of AS sites is defined by interactions between trans-acting splicing factors and cis-acting splicing elements at pre-mRNAs.

Furthermore, several splicing factors have been demonstrated to regulate AS events in stem cell maintenance and differentiation. For example, using CLIP-seq (cross-linking and immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing) technology, the FOX2 splicing factor has been shown to bind to sequences that encode many splicing regulators in human ESCs, demonstrating a potential upstream role of FOX2 in regulating AS in ESCs (Yeo et al., 2009). Consistent with its important roles in ESCs, knockdown of FOX2 leads to ESC cell death (Yeo et al., 2009). The conserved FOX1/2-binding motif has also been found near alternatively spliced sites for genes expressed in neural progenitor cells (Yeo et al., 2007) and various human tissues (Wang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008), suggesting that FOX1/2 might have a broad role in regulating tissue-specific AS events. Another splicing factor, polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB), is important for ESC proliferation and early embryonic development (Shibayama et al., 2009), and it also regulates both neuronal and muscle cell differentiation. In the central nervous system, PTB is restrictively expressed in neuronal precursor cells, whereas its paralogue nPTB is specifically expressed in post-mitotic neurons. Since PTB and nPTB regulate distinct AS events, they are major regulators of isoform switching during neural differentiation (Boutz et al., 2007b). In muscle cells, PTB and nPTB are highly expressed in precursor myoblasts where they repress inclusion of certain exons of target genes, whereas in differentiated myotubes, expression of PTB and nPTB is repressed, leading to inclusion of the particular exons for target genes (Boutz et al., 2007a). Another example is the 68 kDa Src substrate associated during mitosis (SAM68) RBP, which also regulates AS events critical for neural differentiation (Chawla et al., 2009) and mesenchymal cell differentiation (Richard et al., 2005).

Intriguingly, the splicing factors themselves might be subject to dynamic regulation as well, adding another layer of complexity. For example, in the Drosophila male germline lineage, splicing factors are highly enriched in undifferentiated cells, but they are downregulated in differentiating cells, suggesting that their expression levels are controlled by developmental programming (Gan et al., 2010). In addition, during both neural and cardiac differentiation of ESCs, genes regulating RNA splicing themselves undergo robust AS (Salomonis et al., 2009), for example, PTB and nPTB which have mutually exclusive expression in the nervous system. This expression pattern is partly regulated by AS. That is, in precursor cells, PTB induces splicing of nPTB into an isoform that subsequently undergoes NMD (Boutz et al., 2007b). In addition, during myoblast differentiation, the level of splicing regulators also changes dynamically (Bland et al., 2010). For instance, nPTB is downregulated during muscle differentiation by a muscle-specific microRNA, miR-133, providing a great example illustrating how these two post-transcriptional mechanisms (i.e., AS and microRNA) coordinate in regulating cellular differentiation (Bland and Cooper, 2007; Boutz et al., 2007a). These observations, together with the identification of many splicing factor binding sites at regions that are differentially spliced, demonstrate that AS events are tightly controlled during cellular differentiation and that the expression or AS of splicing factors may contribute to this.

Regulation of isoform switching during stem cell differentiation by epigenetic mechanisms: splicing code vs. epigenetic code

Increasing evidence demonstrates that splicing occurs concurrently with mRNA transcription (Allemand et al., 2008). This feature allows regulators of transcription, such as chromatin factors, to control splicing. Recent studies demonstrate two major epigenetic mechanisms in regulating AS: histone modifications and control of RNA Pol II processivity. Because histone modifications also play a profound role in regulating Pol II processivity, these two mechanisms may exhibit crosstalk.

In stem cells, modified histones could determine choice of splicing sites by directly recruiting chromatin-associated proteins and splicing factors. One example comes from studying chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein-1 (CHD1), which is required for maintaining the chromatin landscape and pluripotency of mouse ESCs (Gaspar-Maia et al., 2009). CHD1 recognizes the H3K4me3 histone modification. Interestingly, CHD1 physically interacts with spliceosome components. Furthermore, depletion of CHD1 results in malfunction of spliceosomes, which leads to failure of AS at a set of target genes (Sims et al., 2007). Another example comes from studying human mesenchymal stem cells. In this case, the alternatively spliced third exon of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 gene (FGFR2) is labeled by H3K36me3, a histone modification for transcriptional elongation (Barski et al., 2007). The H3K36me3 mark is subsequently recognized by the histone tail-binding MORF-related protein 15, followed by the recruitment of PTBto a splicing silencer element, which regulates the exclusion of this exon in mesenchymal stem cells (Luco et al., 2010). Since splicing is coupled with transcription, the particular histone modifications that act with splicing machinery are usually associated with transcriptional activation, such as the H3K4me3 and the H3K36me3 histone modifications. We anticipate that future studies will address how epigenetic mechanisms contribute to specific splicing codes for stem cell pluripotency, as well as their proper differentiation.

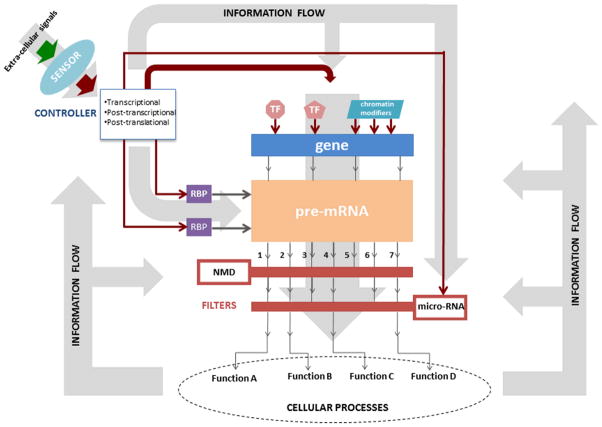

The processivity of Pol II determines the rate of transcription and may also affect choices of AS, as has been reported in stressed cells (Munoz et al., 2009), neurons (Schor et al., 2009), and small interfering RNA (siRNA)-treated cells (Allo et al., 2009). It has been shown that Pol II is more abundant at the exonic region than at introns, suggesting that slow movement of Pol II along exons may allow precise determination of exon-intron boundaries (Schwartz et al., 2009). On the other hand, nucleosomes are found to have a higher occupancy at exons than at introns in various organisms [reviewed by (Schwartz and Ast, 2010)]. Because high nucleosome density limits Pol II elongation rate, differential occupancy of nucleosome along the genome of different cells may lead to their distinct splicing pattern. Intriguingly, recent studies reveal that a DNA-binding protein, CTCF, promotes inclusion of a weak exon by pausing Pol II at specific splicing sites. On the other hand, such a pause of Pol II is prevented by DNA methylation through inhibition of CTCF binding, providing strong evidence that epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, regulate AS through a DNA-binding protein (Shukla et al., 2011). Based on these reports, it is likely that epigenetic mechanisms not only determine gene expression level but also regulate splicing pattern. However, since most of the data have been obtained in cultured cells, more research will be needed to understand how epigenetic mechanisms regulate stem cell-specific splicing events in various organisms [see Figure 1 and reviews (Eun et al., 2010; Luco et al., 2011; Luco and Misteli, 2011)].

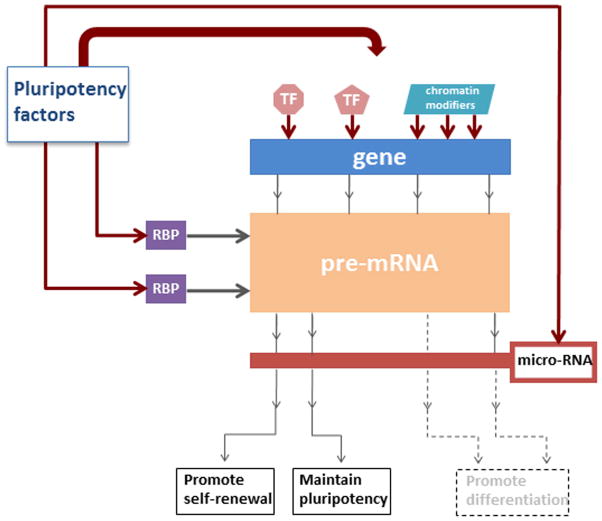

Figure 1.

Figure 1A: A gene-centric view of the cellular information processing system (CIPS), see text for detailed explanation.

Figure 1B: An example of applying the cellular information processing system (CIPS) framework to explain stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency.

A multitude scenario can be used to explain how AS of pre-mRNAs can contribute to self-renewal and maintenance of multipotency/pluripotency of stem cells, as well as their cellular differentiation. Some possible scenarios are shown here: the general pluripotency factors can modulate the activity of RBPs which regulate pre-mRNA splicing. Additionally, the pluripotency factors can affect splicing indirectly by changing the chromatin template of the corresponding genes. The dotted line coming out from the “pre-mRNA” rectangle symbolizes a particular isoform, which is not produced by the splicing process. An isoform produced by the splicing process may still be filtered out by a micro-RNA filter as depicted by the dotted line coming out from the filter. The production of the protein that promotes cellular differentiation is thus inhibited. Instead, the protein that promotes self-renewal and maintains pluripotency is produced. See OCT4 and FOXP1 examples in the text. Abbreviations: TF - transcription factor; RBP -RNA binding protein; NMD - nonsense mediated decay.

Differential splicing and information flow in stem cell lineages

In the previous sections, we reviewed the involvement of AS in stem cell maintenance and differentiation. In this section, we will attempt to unify these different events using information and communication theory metaphors.

Recently, some basic concepts from information theory have been used to characterize the complexity and dynamics of alternative splicing. For example, it was reported that isoform entropy was significantly higher in cancer cells than in normal tissues (Ritchie et al., 2008). We also observed that isoform entropy decreases upon differentiation of male GSCs in Drosophila (Gan et al., 2010). A related observation in ESC differentiation was made in (Wu et al., 2010). In order to describe the generic isoform switching that should involve at least two isoforms, a recent study uses “Jensen-Shannon distance” as an information-theoretic approach to characterize changes in information content of transcriptomes during cellular differentiation (Trapnell et al., 2010).

The signals received by stem cells from their niches allow them to maintain their identity and activity. These signals comprise different types of interactions such as direct cell-cell contacts and cell-extracellular matrix contacts. Shannon entropy is a measure of uncertainty about a system (Cover et al., 1991). We speculate that decrease in isoform entropy is related to information inflow that guides the stem cell differentiation process. The pre-mRNA splicing process is tightly coupled to the cellular information processing systems (CIPS). Therefore, the functional meaning of AS in stem cell maintenance and differentiation can be precisely understood only in the context of the CIPS.

The pre-mRNA splicing process in the context of the CIPS is schematically depicted in Figure 1A. The extracellular signals activate cell-surface receptors, which, in turn, relay the information down the signal transduction pathways into the stem cell. The cell-surface receptors and the signal transduction pathways are collectively denoted as “sensor”. The sensor also receives input from intracellular processes; thus, the output of the sensor also depends on the intrinsic state of the cell. The signal transduction pathways impinge upon transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational gene-regulatory networks, which are collectively denoted as “controller”. This is depicted as the output of the sensor feeding into the controller. Transcription factors or chromatin modifiers that bind to the regulatory elements, such as the enhancer and promoter regions of genes, or modify chromatin are themselves subject to regulation by the controller (shown as a thick red line with an arrow toward transcription factors or chromatin modifiers). Based on the co-transcriptional nature of alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs, some of the histone modifications involved in transcription initiation and elongation may influence pre-mRNA splicing process. The transmission of information from the chromatin template to pre-mRNA of a gene is depicted as arrows extending from “gene” to “pre-mRNA”. The binding of RBPs, such as FOX2 and PTB discussed above, to splicing regulatory sequences, such as splicing enhancers or silencers, modulate pre-mRNA splicing. RBPs are themselves subject to regulation by the controller.

The output of pre-mRNA splicing is a set of spliced mRNA isoforms (denoted as 1 to 7 in Fig. 1A). The relative levels of these isoforms are determined by upstream regulatory processes. In other words, the information inflow from upstream processes shapes the information content of mRNA isoforms. The spliced isoforms then pass through various “filters”. NMD can be interpreted as a filter (e.g., isoform 5 does not pass the NMD filter and gets degraded in Fig. 1A). Translational inhibition or mRNA degradation by microRNAs can be treated as another filter (e.g., isoforms 3 and 6 do not pass the microRNA filter and get degraded and/or are translationally inhibited in Fig. 1A). The Serca2 gene in mouse ESC, as discussed above, is an example of a microRNA filter. The microRNAs are themselves subject to regulation by the controller. The products of mRNA isoforms that pass all post-transcriptional and post-translational filters go on to produce functional proteins that act in various cellular processes. Examples of such cellular processes include maintenance of pluripotency and repression of differentiation gene expression in stem cells. The outputs of these cellular processes then have feedback to the CIPS.

The schematic framework shown in Figure 1A may accommodate many scenarios regarding how AS contributes to the self-renewal and pluripotency of stem cells, as well as their cellular differentiation. All examples discussed in this review can be understood using this framework. Some additional possible scenarios are shown in Figure 1B.

The information/communication theory metaphor of CIPS described here is qualitative and does not necessarily reflect all events at the molecular level. In order for such a framework to be useful, a quantitative theory of information flow dynamics in CIPS is needed. We predict that as more high-throughput measurements of the dynamic activity of components in CIPS become available in cellular differentiation, the information-theoretic methods will be increasingly used to characterize information flow in biological networks.

Conclusions and Perspectives

In summary, new high-throughput technology allows digital inventory of RNA abundance and isoforms, which provides new opportunities to study how changing AS patterns accompany or regulate stem cell differentiation processes. Although most of the current work cannot determine whether the observed pattern switching correlates with, or contributes to, stem cell maintenance and differentiation (Nelles and Yeo, 2010), molecular genetics assays using animal models or cultured stem cells can test the biological consequence of disrupting such patterns in stem cell systems, in vivo or in vitro. Furthermore, recent research on human iPSCs has paved the way for regenerative medicine. It will be interesting to determine whether the stem cell-specific splicing code discussed in this review also exists in iPSCs. If it does, we will want to know what mechanism underlies isoform switching during normal stem cell differentiation such that it then reverses itself during the reprogramming process to become iPSCs. We anticipate more exciting work will emerge to understand the biological significance of mRNA isoform switching during stem cell differentiation, thus facilitating the application of stem cells in regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to people whose work cannot be discussed in this review due to space limitation. We thank Dr. Keji Zhao and Chen lab members for their critical comments on this review. The work in the Chen lab has been supported by Research Grant No. 05-FY09-88 from the March of Dimes Foundation, the R00HD055052 NIH Pathway to Independence Award, R21 HD065089 and R01HD065816 from NICHD, the 49th Mallinckrodt Scholar Award from the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation, the American Federation of Aging Research, the Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Johns Hopkins University start-up funding. And I.C. is supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

References

- Allemand E, Batsche E, Muchardt C. Splicing, transcription, and chromatin: a menage a trois. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allo M, Buggiano V, Fededa JP, Petrillo E, Schor I, de la Mata M, Agirre E, Plass M, Eyras E, Elela SA, et al. Control of alternative splicing through siRNA-mediated transcriptional gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:717–24. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlasi Y, Mowla SJ, Ziaee SA, Gokhale PJ, Andrews PW. OCT4 spliced variants are differentially expressed in human pluripotent and nonpluripotent cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:3068–74. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, Spivakov M, Jorgensen HF, John RM, Gouti M, Casanova M, Warnes G, Merkenschlager M, et al. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:532–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash Y, Calarco JA, Gao W, Pan Q, Wang X, Shai O, Blencowe BJ, Frey BJ. Deciphering the splicing code. Nature. 2010;465:53–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland CS, Cooper TA. Micromanaging alternative splicing during muscle differentiation. Dev Cell. 2007;12:171–2. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland CS, Wang ET, Vu A, David MP, Castle JC, Johnson JM, Burge CB, Cooper TA. Global regulation of alternative splicing during myogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7651–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutz PL, Chawla G, Stoilov P, Black DL. MicroRNAs regulate the expression of the alternative splicing factor nPTB during muscle development. Genes Dev. 2007a;21:71–84. doi: 10.1101/gad.1500707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutz PL, Stoilov P, Li Q, Lin CH, Chawla G, Ostrow K, Shiue L, Ares M, Jr, Black DL. A post-transcriptional regulatory switch in polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins reprograms alternative splicing in developing neurons. Genes Dev. 2007b;21:1636–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.1558107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Mathur D, Jaenisch R. Molecular control of pluripotency. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006a;16:455–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Plath K, Zeitlinger J, Brambrink T, Medeiros LA, Lee TI, Levine SS, Wernig M, Tajonar A, Ray MK, et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006b;441:349–53. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla G, Lin CH, Han A, Shiue L, Ares M, Jr, Black DL. Sam68 regulates a set of alternatively spliced exons during neurogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:201–13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01349-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Stem cells: What can we learn from flies? Fly (Austin) 2008:2. doi: 10.4161/fly.5872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover TM, Thomas JA. Elements of information theory. 1. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Jena S, Levasseur DN. Alternative Splicing Produces Nanog Protein Variants with Different Capacities for Self-Renewal and Pluripotency in Embryonic Stem Cells. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eun SH, Gan Q, Chen X. Epigenetic regulation of germ cell differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:737–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–6. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller MT, Spradling AC. Male and female Drosophila germline stem cells: two versions of immortality. Science. 2007;316:402–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1140861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabut M, Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Wang X, Slobodeniuc V, O’Hanlon D, Sung HK, Alvarez M, Talukder S, Pan Q, Mazzoni EO, et al. An alternative splicing switch regulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell. 2011;147:132–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Q, Chepelev I, Wei G, Tarayrah L, Cui K, Zhao K, Chen X. Dynamic regulation of alternative splicing and chromatin structure in Drosophila gonads revealed by RNA-seq. Cell Res. 2010;20:763–83. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar-Maia A, Alajem A, Polesso F, Sridharan R, Mason MJ, Heidersbach A, Ramalho-Santos J, McManus MT, Plath K, Meshorer E, et al. Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:863–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Nayernia K, Maier LS, Wagner S, Dressel R, Lee JH, Nolte J, Wolf F, Li M, Engel W, et al. Pluripotency of spermatogonial stem cells from adult mouse testis. Nature. 2006;440:1199–203. doi: 10.1038/nature04697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurica MS, Moore MJ. Pre-mRNA splicing: awash in a sea of proteins. Mol Cell. 2003;12:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Inoue K, Lee J, Yoshimoto M, Ogonuki N, Miki H, Baba S, Kato T, Kazuki Y, Toyokuni S, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from neonatal mouse testis. Cell. 2004;119:1001–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Chu J, Shen X, Wang J, Orkin SH. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:1049–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunarso G, Wong KY, Stanton LW, Lipovich L. Detailed characterization of the mouse embryonic stem cell transcriptome reveals novel genes and intergenic splicing associated with pluripotency. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau LF, Inada M, Green RE, Wengrod JC, Brenner SE. Unproductive splicing of SR genes associated with highly conserved and ultraconserved DNA elements. Nature. 2007;446:926–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim HK, Rho JY, Han YM, Kim J. The human OCT-4 isoforms differ in their ability to confer self-renewal. J Biol Chem. 2006a;281:33554–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, Guenther MG, Levine SS, Kumar RM, Chevalier B, Johnstone SE, Cole MF, Isono K, et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006b;125:301–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemischka IR, Pritsker M. Alternative splicing increases complexity of stem cell transcriptome. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:347–51. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.4.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh YH, Wu Q, Chew JL, Vega VB, Zhang W, Chen X, Bourque G, George J, Leong B, Liu J, et al. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2006;38:431–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick VP, Morris LX, Fox DT, Spradling A. Drosophila stem cell niches: a decade of discovery suggests a unified view of stem cell regulation. Dev Cell. 2011;21:159–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luco RF, Allo M, Schor IE, Kornblihtt AR, Misteli T. Epigenetics in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 2011;144:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luco RF, Misteli T. More than a splicing code: integrating the role of RNA, chromatin and non-coding RNA in alternative splicing regulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luco RF, Pan Q, Tominaga K, Blencowe BJ, Pereira-Smith OM, Misteli T. Regulation of alternative splicing by histone modifications. Science. 2010;327:996–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1184208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:7634–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayshar Y, Rom E, Chumakov I, Kronman A, Yayon A, Benvenisty N. Fibroblast growth factor 4 and its novel splice isoform have opposing effects on the maintenance of human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2008;26:767–74. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, Issac B, Lieberman E, Giannoukos G, Alvarez P, Brockman W, Kim TK, Koche RP, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–60. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar A, Georgopoulos K. The Ikaros gene encodes a family of functionally diverse zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8292–303. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Kimble J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature. 2006;441:1068–74. doi: 10.1038/nature04956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz MJ, Perez Santangelo MS, Paronetto MP, de la Mata M, Pelisch F, Boireau S, Glover-Cutter K, Ben-Dov C, Blaustein M, Lozano JJ, et al. DNA damage regulates alternative splicing through inhibition of RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell. 2009;137:708–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelles DA, Yeo GW. Alternative splicing in stem cell self-renewal and diferentiation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;695:92–104. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7037-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni JZ, Grate L, Donohue JP, Preston C, Nobida N, O’Brien G, Shiue L, Clark TA, Blume JE, Ares M., Jr Ultraconserved elements are associated with homeostatic control of splicing regulators by alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated decay. Genes Dev. 2007;21:708–18. doi: 10.1101/gad.1525507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritsker M, Doniger TT, Kramer LC, Westcot SE, Lemischka IR. Diversification of stem cell molecular repertoire by alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502132102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S, Zhen S, Roumiantsev S, McDonald LT, Yuan GC, Orkin SH. Differential roles of Sall4 isoforms in embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5364–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00419-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S, Torabi N, Franco GV, Tremblay GA, Chen T, Vogel G, Morel M, Cleroux P, Forget-Richard A, Komarova S, et al. Ablation of the Sam68 RNA binding protein protects mice from age-related bone loss. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie W, Granjeaud S, Puthier D, Gautheret D. Entropy measures quantify global splicing disorders in cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Jamieson CH, Weissman IL. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132:681–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomonis N, Nelson B, Vranizan K, Pico AR, Hanspers K, Kuchinsky A, Ta L, Mercola M, Conklin BR. Alternative splicing in the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into cardiac precursors. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomonis N, Schlieve CR, Pereira L, Wahlquist C, Colas A, Zambon AC, Vranizan K, Spindler MJ, Pico AR, Cline MS, et al. Alternative splicing regulates mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10514–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912260107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor IE, Rascovan N, Pelisch F, Allo M, Kornblihtt AR. Neuronal cell depolarization induces intragenic chromatin modifications affecting NCAM alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810666106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Ast G. Chromatin density and splicing destiny: on the cross-talk between chromatin structure and splicing. EMBO J. 2010;29:1629–36. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Meshorer E, Ast G. Chromatin organization marks exon-intron structure. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:990–5. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama M, Ohno S, Osaka T, Sakamoto R, Tokunaga A, Nakatake Y, Sato M, Yoshida N. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein is essential for early mouse development and embryonic stem cell proliferation. FEBS J. 2009;276:6658–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S, Kavak E, Gregory M, Imashimizu M, Shutinoski B, Kashlev M, Oberdoerffer P, Sandberg R, Oberdoerffer S. CTCF-promoted RNA polymerase II pausing links DNA methylation to splicing. Nature. 2011;479:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nature10442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims RJ, 3rd, Millhouse S, Chen CF, Lewis BA, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Manley JL, Reinberg D. Recognition of trimethylated histone H3 lysine 4 facilitates the recruitment of transcription postinitiation factors and pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2007;28:665–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AG. Embryo-derived stem cells: of mice and men. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:435–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock JK, Giadrossi S, Casanova M, Brookes E, Vidal M, Koseki H, Brockdorff N, Fisher AG, Pombo A. Ring1-mediated ubiquitination of H2A restrains poised RNA polymerase II at bivalent genes in mouse ES cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1428–35. doi: 10.1038/ncb1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan M, Schulz MH, Richard H, Magen A, Klingenhoff A, Scherf M, Seifert M, Borodina T, Soldatov A, Parkhomchuk D, et al. A global view of gene activity and alternative splicing by deep sequencing of the human transcriptome. Science. 2008;321:956–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1160342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136:701–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Burge CB. Splicing regulation: from a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. RNA. 2008;14:802–13. doi: 10.1261/rna.876308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JQ, Habegger L, Noisa P, Szekely A, Qiu C, Hutchison S, Raha D, Egholm M, Lin H, Weissman S, et al. Dynamic transcriptomes during neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells revealed by short, long, and paired-end sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5254–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914114107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Chen X, Zhang J, Loh YH, Low TY, Zhang W, Sze SK, Lim B, Ng HH. Sall4 interacts with Nanog and co-occupies Nanog genomic sites in embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24090–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita YM, Yuan H, Cheng J, Hunt AJ. Polarity in stem cell division: asymmetric stem cell division in tissue homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001313. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo GW, Coufal NG, Liang TY, Peng GE, Fu XD, Gage FH. An RNA code for the FOX2 splicing regulator revealed by mapping RNA-protein interactions in stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:130–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo GW, Xu X, Liang TY, Muotri AR, Carson CT, Coufal NG, Gage FH. Alternative splicing events identified in human embryonic stem cells and neural progenitors. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:1951–67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang Z, Castle J, Sun S, Johnson J, Krainer AR, Zhang MQ. Defining the regulatory network of the tissue-specific splicing factors Fox-1 and Fox-2. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2550–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.1703108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Chipperfield H, Melton DA, Wong WH. A gene regulatory network in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]