Abstract

Objective To assess the long term effect of United Kingdom legislation introduced in September 1998 to restrict pack sizes of paracetamol on deaths from paracetamol poisoning and liver unit activity.

Design Interrupted time series analyses to assess mean quarterly changes from October 1998 to the end of 2009 relative to projected deaths without the legislation based on pre-legislation trends.

Setting Mortality (1993-2009) and liver unit activity (1995-2009) in England and Wales, using information from the Office for National Statistics and NHS Blood and Transplant, respectively.

Participants Residents of England and Wales.

Main outcome measures Suicide, deaths of undetermined intent, and accidental poisoning deaths involving single drug ingestion of paracetamol and paracetamol compounds in people aged 10 years and over, and liver unit registrations and transplantations for paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity.

Results Compared with the pre-legislation level, following the legislation there was an estimated average reduction of 17 (95% confidence interval −25 to −9) deaths per quarter in England and Wales involving paracetamol alone (with or without alcohol) that received suicide or undetermined verdicts. This decrease represented a 43% reduction or an estimated 765 fewer deaths over the 11¼ years after the legislation. A similar effect was found when accidental poisoning deaths were included, and when a conservative method of analysis was used. This decrease was largely unaltered after controlling for a non-significant reduction in deaths involving other methods of poisoning and also suicides by all methods. There was a 61% reduction in registrations for liver transplantation for paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity (−11 (−20 to −1) registrations per quarter). But no reduction was seen in actual transplantations (−3 (−12 to 6)), nor in registrations after a conservative method of analysis was used.

Conclusions UK legislation to reduce pack sizes of paracetamol was followed by significant reductions in deaths due to paracetamol overdose, with some indication of fewer registrations for transplantation at liver units during the 11 years after the legislation. The continuing toll of deaths suggests, however, that further preventive measures should be sought.

Introduction

In many countries, self poisoning with paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a common method of suicide and non-fatal self harm, it is responsible for many accidental deaths, and is a frequent cause of hepatotoxicity and liver unit admissions.1 2 3 4 5 Legislation was introduced by the United Kingdom government, following recommendations by the UK Medicines Control Agency (later the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency) in September 1998 that restricted pack sizes of paracetamol (including compounds) sold over the counter. Packs were restricted to a maximum of 32 tablets in pharmacies and to 16 tablets for non-pharmacy sales.6 7

This policy was introduced because of the large number of people taking paracetamol overdoses,2 8 9 and increasing numbers of deaths10 and liver transplants11 due to paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity. Another reason for the legislation was knowledge gained from interviewing people who had presented to hospital after paracetamol overdoses, many of whom reported that the act was often impulsive and involved use of drugs already stored in the home.12 13

Our research group showed that this implementation had benefits during the first few years after the legislation in terms of paracetamol related deaths, liver transplants, and numbers of tablets consumed in overdoses.14 15 Other studies supported these findings.16 17 However, some commentators have questioned the effect of the legislation.18 Furthermore, other researchers who re-examined national data19 suggested that decreases in mortality from paracetamol poisoning simply reflected trends in other poisoning deaths (although there were methodological issues with these findings20). They also suggested that the reduction in paracetamol related deaths preceded implementation of the legislation.21 In Scotland, no evidence of an effect of the legislation on deaths was found.22 23 More long term studies are needed to assess whether the legislation has been a success.17

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the potential long term effect of the legislation in England and Wales on poisoning deaths, especially suicides, and on liver unit activity for paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity, as measured by registration for liver transplantation and actual transplants.

Methods

Study design

We used data for poisoning deaths in England and Wales between 1993 and 2009 to examine the effect of the 1998 legislation on deaths. We also used data for liver unit registrations and transplantations in residents of England and Wales between 1995 and 2009 to examine the legislation’s effect on paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity. The effects of the 1998 legislation were assessed in a before and after design, by using interrupted time series.

Outcomes

Deaths

To evaluate the effect of the legislation to reduce paracetamol pack size on suicide, we used data for deaths receiving a suicide verdict and those recorded as death of undetermined intent (“open” verdicts). In England and Wales, it has been customary to assume that most injuries and poisonings of undetermined intent are cases where the harm was self inflicted but there was insufficient evidence to prove that the deceased deliberately intended to kill themselves.24 25

The Office for National Statistics provided quarterly information on drug poisoning deaths (suicides, open verdicts, and accidental poisonings) involving paracetamol, and the more common paracetamol compounds used for self poisoning (paracetamol with codeine, dihydrocodeine, ibuprofen, or aspirin). These data were based on deaths registered in 1993-2009 in England and Wales. We did not include deaths involving co-proxamol, a paracetamol-dextropropoxyphene compound, because dextropropoxyphene is the usual lethal agent in co-proxamol poisonings and the drug was withdrawn in 2007.26

We restricted our analyses to deaths involving single drugs (paracetamol or paracetamol compounds) with or without alcohol, for people aged 10 years and over. This restriction was to avoid contamination of effects where paracetamol was taken with other, perhaps more toxic, drugs (which could have been the cause of death). Similar data were supplied for overall deaths from drug poisoning that received suicide, open, and accidental poisoning verdicts, and for all deaths that received suicide and open verdicts.

Registrations for liver transplantation and actual transplants

Data for all transplant units in the UK between 1995 and 2009 on registrations for liver transplantation and actual liver transplants due to paracetamol poisoning were supplied by UK Transplant (now NHS Blood and Transplant). We restricted our analyses to data for residents of England and Wales aged 10 years and over (paracetamol poisoning in children younger than 10 years is usually accidental).

Statistical analyses

We used interrupted time series analysis to estimate changes in the levels and trends in deaths, liver unit registrations, and liver transplantations following implementation of the 1998 legislation to reduce the pack size of paracetamol. This method controls for the baseline level and trend when estimating expected changes in numbers due to the intervention.27 Specifically, segmented regression analysis28 was used to estimate the mean quarterly numbers of deaths and liver unit registrations and transplantations that might have occurred in the post-intervention period without the legislation, and the numbers that occurred with the legislation. The mean numbers per quarter following the legislation were obtained from best fitted data lines from the regressions, and are better estimates than taking the average of the actual values. The end of the third quarter of 1998 was chosen as the point of intervention.

Our data for deaths comprised 23 quarters in the pre-intervention segment and 45 quarters in the post-intervention segment. For liver unit registrations and transplantations, corresponding data comprised 15 quarters before the legislation and 45 quarters after. Regression coefficients for both level and trend were used to estimate the average absolute differences per quarter (using the mid-point of the post-intervention period; web appendix).

We analysed paracetamol deaths using:

The basic regression model (equation 1, web appendix), which assumed that pre-existing trends in paracetamol deaths would have continued in the absence of the legislation

The basic regression model plus adjustment for potentially confounding trends in “all drug poisoning suicide deaths” and “all suicide deaths” by inclusion of “all drug suicide deaths excluding paracetamol” and “all suicide deaths excluding paracetamol” as covariates

A conservative estimate of the absolute effect, which assumed no increase in the incidence of paracetamol associated deaths after the legislation (in the absence of this intervention). In this conservative estimate, the absolute effect of the legislation was determined as the difference between the outcome expected at the last point of the pre-intervention period and the mid-point of the post-intervention period

For analysis of liver unit registrations and transplantations, we used the basic regression model and the conservative estimate analysis.

We found some first order autocorrelation in the data; therefore, Cochrane-Orcutt autoregression was used to adjust for this, and Durbin Watson statistics were close to the preferred value of 2. We carried out a sensitivity analysis to determine whether our results changed when January 1998 was used as the date when trends changed. This date corresponded to the date when changes to the paracetamol packaging sizes began to occur (nine months before the legislation was implemented). Analyses of trends in deaths and liver unit registrations and transplantations were conducted using Stata version 10.0.29

Results

Deaths

Table 1 shows the number of deaths in England and Wales between 1993 and 2009 due to poisoning with (1) any drugs and (2) paracetamol specifically, which received suicide, open, and accidental poisoning verdicts. Paracetamol poisoning deaths constituted about 6-10% of such deaths.

Table 1.

Suicide, open verdict and accidental deaths in England and Wales for people aged 10 years and over, 1993-2009

| Year | All causes (suicide, open) | All drugs | Paracetamol | Paracetamol compound* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide, open | Suicide, open, accidental | Suicide, open |

Suicide, open, accidental | Suicide, open |

Suicide, open, accidental | ||||

| 1993 | 5182 | 1314 | 1897 | 132 (10.0) | 181 (9.5) | 17 (1.3) | 22 (1.2) | ||

| 1994 | 5090 | 1298 | 2003 | 126 (9.7) | 163 (8.1) | 15 (1.2) | 20 (1.0) | ||

| 1995 | 5127 | 1390 | 2140 | 122 (8.8) | 155 (7.2) | 24 (1.7) | 27 (1.3) | ||

| 1996 | 4910 | 1325 | 2103 | 121 (9.1) | 158 (7.5) | 24 (1.8) | 26 (1.2) | ||

| 1997 | 4830 | 1406 | 2252 | 149 (10.6) | 204 (9.1) | 21 (1.5) | 27 (1.2) | ||

| 1998 | 5347 | 1432 | 2246 | 135 (9.4) | 183 (8.1) | 16 (1.1) | 20 (1.9) | ||

| 1999 | 5241 | 1414 | 2294 | 113 (8.0) | 150 (6.5) | 29 (2.1) | 33 (1.4) | ||

| 2000 | 5081 | 1309 | 2143 | 90 (6.9) | 123 (5.7) | 29 (2.2) | 31 (1.4) | ||

| 2001 | 4904 | 1280 | 2176 | 108 (8.4) | 142 (6.5) | 18 (1.4) | 27 (1.2) | ||

| 2002 | 4762 | 1227 | 1983 | 90 (7.3) | 124 (6.3) | 22 (1.8) | 28 (1.4) | ||

| 2003 | 4811 | 1194 | 1843 | 91 (7.6) | 120 (6.5) | 22 (1.8) | 28 (1.5) | ||

| 2004 | 4883 | 1246 | 2008 | 88 (7.1) | 127 (6.3) | 31 (2.5) | 40 (2.0) | ||

| 2005 | 4718 | 1154 | 1926 | 92 (8.0) | 126 (6.5) | 33 (2.9) | 37 (1.9) | ||

| 2006 | 4513 | 979 | 1821 | 92 (9.4) | 131 (7.2) | 35 (3.6) | 46 (2.5) | ||

| 2007 | 4322 | 888 | 1852 | 66 (7.4) | 90 (4.9) | 23 (2.6) | 36 (1.9) | ||

| 2008 | 4603 | 884 | 2071 | 61 (6.9) | 106 (5.1) | 26 (2.9) | 44 (2.1) | ||

| 2009 | 4682 | 898 | 2185 | 69 (7.7) | 125 (5.7) | 26 (2.9) | 39 (1.8) | ||

Open=open verdict; accidental=accidental poisoning. Data are no or no (%) of deaths.

*Compounds include paracetamol and codeine, paracetamol and dihydrocodeine, paracetamol and ibuprofen, and paracetamol and aspirin.

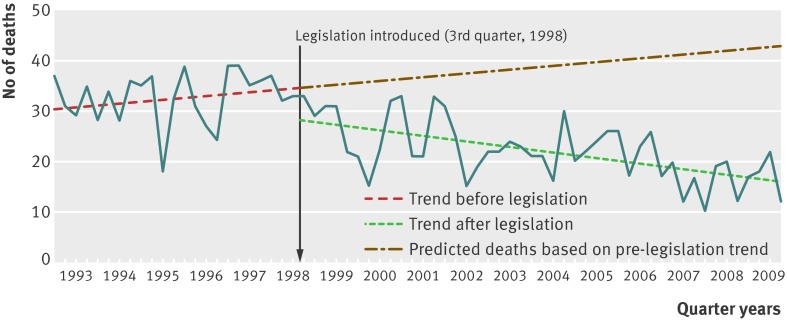

Regression analysis of quarterly data indicated a significant decrease corresponding to the 1998 legislation in both level and trend (that is, the slope) in deaths in England and Wales involving paracetamol that received a suicide or open verdict (fig 1; web table). The estimated average reduction in number of deaths was 17 (95% confidence interval −25 to −9) per quarter in the post-intervention period compared with the expected number based on trends in the pre-intervention period (table 2). This change equated to an overall decrease of about 43% in the post-legislation period of 11¼ years, or 765 fewer deaths than would have been predicted based on trends between 1993 and September 1998. An overall decrease of 35% was found when using a conservative method of analysis (table 2).

Fig 1 Suicide and open verdict deaths involving paracetamol only, in people aged 10 years and over in England and Wales, 1993-2009, and best fit regression lines related to 1998 legislation

Table 2.

Estimated effects of 1998 legislation on poisoning deaths involving paracetamol, for people aged 10 years and over in England and Wales in 1993-2009. Data are mean estimated no of deaths per quarter year, unless stated otherwise

| Estimate of absolute effect (October 1998 to 2009)* | Conservative† estimate of absolute effect (October 1998 to 2009)* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without legislation‡ |

With legislation‡ |

Difference (95% CI)§ | Without legislation‡ |

With legislation‡ |

Difference (95% CI)§ | ||

| Suicide, open death | |||||||

| Paracetamol | 39 | 22 | −17 (−25 to −9) | 34 | 22 | −12 (−20 to −4) | |

| All drug poisoning (except paracetamol) |

350 | 263 | −87 (−145 to −29) | 321 | 263 | −57 (−115 to 1) | |

| Paracetamol (adjusted)¶ | 28 | 14 | −14 (−23 to −5) | 24 | 14 | −10 (−19 to −2) | |

| Paracetamol (adjusted)** | 20 | 4 | −16 (−25 to −8) | 16 | 4 | −12 (−20 to −3) | |

| Paracetamol compounds | 5 | 6 | 1 (−5 to 7) | 5 | 6 | 1 (−5 to 8) | |

| All drug poisoning | 388 | 285 | −103 (−166 to −40) | 355 | 285 | −70 (−132 to −7) | |

| All causes | 1228 | 1198 | −30 (−199 to 140) | 1252 | 1198 | −54 (−224 to 115) | |

| Suicide, open death, accidental poisoning | |||||||

| Paracetamol | 53 | 31 | −22 (−30 to −14) | 46 | 31 | −15 (−23 to −7) | |

| All drug poisoning (except paracetamol) |

580 | 480 | −100 (−225 to 23) | 513 | 480 | −33 (−158 to 90) | |

| Paracetamol (adjusted)¶ | 41 | 21 | −20 (−32 to −8) | 35 | 21 | −14 (−26 to −2) | |

| Paracetamol compounds | 7 | 9 | 2 (−4 to 8) | 6 | 9 | 3 (−3 to 9) | |

| All drug poisoning | 612 | 493 | −119 (−249 to 11) | 540 | 493 | −47 (−177 to 83) | |

*Using interrupted time series segmented regression analysis,28 where the intervention point is taken as third quarter of 1998.

†Conservative estimate assumes flat trend in post-legislation period had the legislation not occurred.

‡Estimated for the mid-point quarter of October 1998 to 2009.

§Absolute difference of estimated number with legislation and estimated number without, taken at the mid-point of the post-intervention period. Confidence intervals taken from Stata results or calculated according to reference 37.

¶Adjusted by including all deaths from drug poisoning (excluding paracetamol) that received suicide or open verdicts, as a covariate in regression.

**Adjusted by including all suicide and open verdict deaths (except paracetamol) by all methods as a covariate in regression.

We also saw a reduction in all deaths from drug poisoning (excluding paracetamol) receiving a suicide or open verdict during the post-legislation period (−87 deaths (95% confidence interval −145 to −29) per quarter), although this decrease was smaller in magnitude (25%) and was not associated with the step change seen for paracetamol after the introduction of the 1998 legislation. When the change in paracetamol deaths was adjusted to take account of the fall in poisoning deaths involving other drugs, the decline in paracetamol deaths changed very little (table 2). Adjustment for changes in the overall suicide rate also made little difference to the results. Similar results were found when accidental poisoning deaths involving paracetamol were included with suicides and open verdicts (table 2). The reduction in deaths in the post-legislation period when accidents were included equated to 990 fewer deaths than expected based on continuation of the pre-legislation trend had the legislation not occurred (−22 deaths (−30 to −14) per quarter). Although suicides (including open verdicts) involving any method showed a significant reduction during the post-legislation period, we saw no step change associated with the legislation (web table).

When the intervention point was moved back nine months to the beginning of 1998 to take account of earlier introduction of packaging changes, there remained a significant reduction in suicide and open verdict deaths involving paracetamol during 1998-2009 but no step change (web table). There was no major change in deaths involving paracetamol compounds after the 1998 legislation (table 2, web table). These deaths represented a relatively small proportion of paracetamol related deaths overall (table 1).

Liver unit activity

Registration for liver transplantation

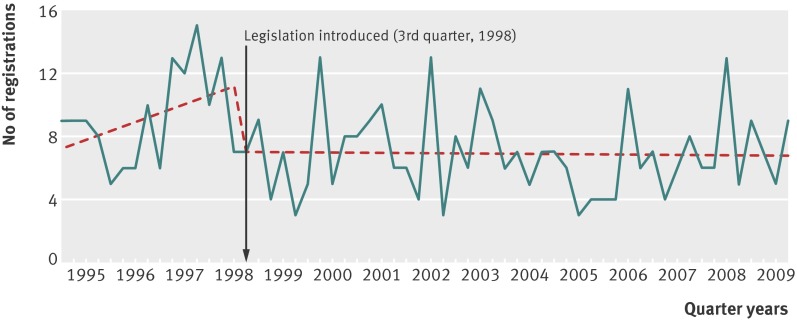

There was a decrease in the level and trend of number of registrations for paracetamol induced liver transplantation in England and Wales residents after the 1998 legislation was introduced (fig 2). The mean quarterly change compared with the expected number based on pre-intervention trends was −11 deaths (95% confidence interval −20 to −1), equating to a 61% reduction in the mean number of deaths per quarter (7 v 18; table 3). This reduction equated to 482 fewer registrations over the 11¼ years after the legislation. We obtained a similar result when we used the beginning of 1998 as the intervention point. A conservative estimate of the absolute change in registrations for liver transplants was smaller, and was not significant.

Fig 2 Paracetamol related registrations for waiting list for liver transplantation, in people aged 10 years and over in England and Wales, 1995-2009, and best fit regression lines related to 1998 legislation

Table 3.

Estimated effects of 1998 legislation on paracetamol related registrations for liver transplantation and liver transplants by people aged 10 years and over in England and Wales, 1995-2009. Data are mean estimated no of registrations per quarter year, unless stated otherwise

| Estimate of absolute effect (October 1998 to 2009)* | Conservative† estimate of absolute effect (October 1998 to 2009)* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without legislation‡ | With legislation‡ | Difference (95% CI)§ | Without legislation‡ | With legislation‡ | Difference (95% CI)§ | ||

| Paracetamol related registrations | |||||||

| Registrations | 18 | 7 | −11 (−20 to −1) | 11 | 7 | −4 (−14 to 5) | |

| Transplants | 8 | 5 | −3 (−12 to 6) | 7 | 5 | −2 (−11 to 7) | |

| All liver transplants | 132 | 149 | 17 (−30 to 63) | 139 | 149 | 10 (−37 to 57) | |

*Using interrupted time series segmented regression analysis,28 where the intervention point is taken as third quarter of 1998.

†Assuming flat trend in post-legislation period had the legislation not occurred.

‡Estimated for the mid-point quarter of October 1998 to 2009.

§Absolute difference of estimated number with legislation and estimated number without, taken at the mid-point of the post-intervention period. Confidence intervals taken from Stata results or calculated according to reference 37.

Liver transplantation

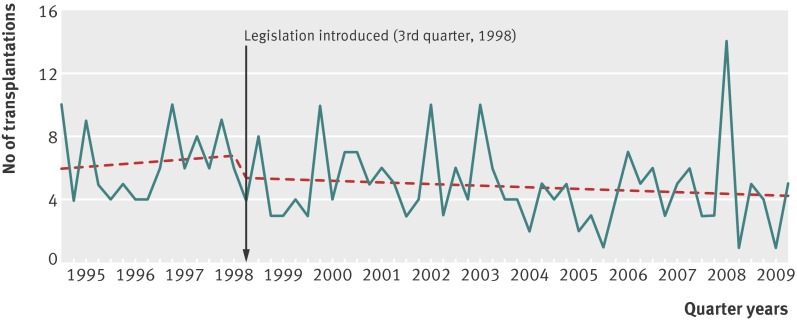

There was a non-significant reduction in liver transplantations for paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity in England and Wales residents after the legislation, when comparing the period from October 1998 to the end of 2009 with the estimated level based on the period from 1995 to September 1998 (fig 3). The estimated mean quarterly change in transplantations was −3 (−12 to 6; table 3). All liver transplantations in the UK showed a small but non-significant increase during the post-legislation period in the mean estimated number per quarter (from 132 before the legislation to 149 after; table 3).

Fig 3 Paracetamol related liver transplantations, in people aged 10 years and over in England and Wales 1995-2009, and best fit regression lines related to 1998 legislation

Discussion

We have shown that the 1998 legislation to restrict pack sizes of paracetamol was associated with a significant reduction in terms of the level and slope in deaths due to paracetamol poisoning in England and Wales over an 11 year period. A decrease was seen both when considering deaths with a coroner’s verdict of suicide and undetermined intent, and when including deaths from accidental poisoning. This effect was found in analyses with estimates based on a continuation of the pre-legislation trend, as well as more conservative estimates assuming no increasing trend in the absence of the legislation.

The downward step change was not apparent when the intervention point was moved back to the beginning of 1998. Although we saw no significant change in deaths due to poisoning with paracetamol compounds, they constituted a small proportion of paracetamol related deaths. Deaths from poisoning with drugs excluding paracetamol also showed a significant reduction between 1998 and 2009, but to a lesser extent than that found for paracetamol. These deaths did not have the step change associated with the 1998 paracetamol legislation date. When we adjusted the paracetamol analyses for underlying trends in poisoning deaths (excluding those that were paracetamol related), the findings for paracetamol deaths were largely unaltered. The 43% reduction in deaths over 11 years was equivalent to 765 fewer deaths with a suicide or open verdict, or 990 fewer deaths if accidental poisoning verdicts were included.

A significant reduction after the legislation was also found for registrations for liver transplantation due to paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity in residents of England and Wales. However, a downward step change was also apparent when the beginning of 1998 was used as the intervention point, and the change was not significant using a conservative estimate of the effect. The 61% reduction in registrations at liver units represented 482 fewer registrations. Although there was also a reduction in liver transplantations of a similar order to registrations, this finding was not significant, owing to smaller numbers.

The reduction in registrations for liver unit transplantation is particularly striking because in 2005 the criteria for registration were broadened, with a lowering of the thresholds for consideration for surgery.30 The reduction in liver transplant registrations may have, in part, resulted from improvements in the early management of patients presenting to hospital with paracetamol poisoning (including administration of the antidote N-acetylcysteine) and the increasing sophistication and success of intensive care support given to patients with acute liver failure induced by paracetamol use.31 These factors could also have accounted for some of the non-significant reduction in the numbers of paracetamol deaths observed over the study period. However, the process of change has been one of continuous evolution and would be unlikely to account for the step change seen in outcomes coincident with the introduction of sales restrictions. Importantly, there has been no decline in hospital presentations in England for non-fatal overdoses of paracetamol after the legislation32; thus, these findings cannot be explained by fewer paracetamol overdoses.

The effect of the 1998 legislation on pack sizes of paracetamol is likely to reflect the fact that many people who intentionally overdose with paracetamol take what is available in the household,13 33 especially if the overdose is impulsive. Also, when people purchase drugs specifically for the purpose of an overdose, the amount of paracetamol available would have been more limited after the legislation, probably even if multiple purchases are made. We previously showed a reduction in the size of non-fatal overdoses of paracetamol after the legislation.15

Despite the apparent benefits of the 1998 legislation, there continues to be a considerable number of deaths each year due to paracetamol poisoning, averaging 121 per year (for suicide, open, and accidental verdicts) between 2000 and 2009 for paracetamol alone with or without alcohol but excluding paracetamol compounds (table 1). The benefits should therefore not lead to complacency.

Further measures might be needed to reduce this death toll. These measures might include stronger enforcement of the legislation.34 Another possibility is a further reduction in pack sizes—some commentators have suggested that the limit should have been set lower.13 18 Another measure might be to reduce the paracetamol content of tablets, similar to the recent reduction of paracetamol (from 500 mg to 325 mg) in prescribed compound preparations introduced by the US Food and Drug Administration.35 However, it would need to be shown that such a further reduction would have no major effect on efficacy of pain relief.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was that we only used data for deaths for poisoning with paracetamol (with or without alcohol), in pure or compound form. We did not use data for deaths where paracetamol was consumed with other drugs. This approach, however, ensured that our findings were restricted primarily to paracetamol, and not substantially affected by changed availability or toxicity of other drugs or compounds.

A strength of the study was that it was based on national data for both deaths and liver unit activity. We have not been able to estimate possible substitution of paracetamol overdoses with other methods of poisoning or self harm, but the non-significant change in total suicides (by all methods) and in suicides by ingestion during the period after the 1998 legislation was downward. This non-significant decrease in all suicides probably indicates that other factors may have favourably influenced suicide rates, and hence might have contributed to the findings for paracetamol poisoning deaths.

Other changes in availability of analgesics during the study included withdrawal of co-proxamol in 200724 and cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors after safety concerns in 2004.36 However, these withdrawals probably would have not influenced the results, and we took account of changes in poisoning deaths in our analyses.

What is already known on this topic

Paracetamol poisoning, which occurs mainly through intentional overdose, is an important worldwide cause of deaths and reason for liver transplantation due to hepatotoxicity

UK legislation implemented in 1998 to restrict pack sizes of paracetamol sold over the counter has shown initial benefits, in terms of non-fatal overdoses and liver unit activity in England and Wales

The long term effect of the legislation has yet to be evaluated

What this study adds

The legislation appears to have had long term benefits in terms of fewer deaths due to paracetamol poisoning, after controlling for changes in overall rates of death by self poisoning and suicide

Less robust evidence suggested a reduction in liver unit registrations and transplantation owing to paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity

Nevertheless, substantial numbers of deaths due to paracetamol poisoning still occur annually, and further preventive measures might be warranted

We thank Claudia Wells at the Office for National Statistics for supplying the mortality data.

Contributors: KH conceived the idea for the study. KH, SS, DG, and NK designed the study. KH, DG, and NK obtained funding. SS, SD, PP, and KH obtained the data. HB conducted the analysis. KH drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors commented on drafts and approved the final version. KH is the guarantor. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0606-1247) as part of a programme of work related to suicide prevention. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health, or the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The funder had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and decision to submit the paper for publication. KH and DG are NIHR senior investigators. KH is also supported by the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, HB by the Department of Health under the NHS Research and Development Programme (DH/DSH2008), and NK by the Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support from the NIHR for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; DG is a member of the Pharmacovigillance Expert Advisory Group of the MHRA; KH, NK, and DG are members of the National Suicide Prevention Strategy Advisory Group; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f403

Web Extra. Extra material as supplied by authors

References

- 1.Gunnell D, Murray V, Hawton K. Use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) for suicide and non-fatal poisoning: world-wide patterns of use and misuse. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2000;30:313-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunnell D, Hawton K, Murray V, Garnier R, Bismuth C, Fagg J, et al. Use of paracetamol for suicide and non-fatal poisoning in the UK and France: are restrictions on availability justified? J Epidemiol Community Health 1997;51:175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gow PJ, Smallwood RA, Angus PA. Paracetamol overdose in a liver transplantation centre: An 8-year experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;14:817-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, et al. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology 2005;42:1364-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Møller LR, Nielsen GL, Olsen ML, Thulstrup AM, Mortensen JT, Sørensen HT. Hospital discharges and 30-day case fatality for drug poisoning: A Danish population-based study from 1979 to 2002 with special emphasis on paracetamol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2004;59:911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Safety of Medicines. Paracetamol and aspirin. Curr Prob Pharmacovigilance 1997;23:9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Medicines (Sales or Supply) (Miscellaneous Provisions) Amendment (No 2) Regulations 1997. Statutory Instrument (1997/2045). The Stationery Office, 1997.

- 8.Bialas MC, Reid PG, Beck P, Lazarus JH, Smith PM, Scorer RC, et al. Changing patterns of self-poisoning in a UK health district. QJM 1996;89:893-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K, Fagg J, Simkin S, Bale E, Bond A. Trends in deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1985-1995. Implications for clinical services and the prevention of suicide. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:556-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray GP. Liver failure induced by paracetamol: avoidable deaths still occur. BMJ 1993;306:157-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernal W. Changing patterns of causation and the use of transplantation in the United Kingdom. Semin Liver Dis 2003;23:227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawton K, Ware C, Mistry H, Hewitt J, Kingsbury S, Roberts D, et al. Why patients choose paracetamol for self poisoning and their knowledge of its dangers. BMJ 1995;310:164.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawton K, Ware C, Mistry H, Hewitt J, Kingsbury S, Roberts D, et al. Paracetamol self-poisoning. Characteristics, prevention and harm reduction. Br J Psychiatry 1996;168:43-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawton K, Townsend E, Deeks JJ, Appleby L, Gunnell D, Bennewith O, et al. Effects of legislation restricting pack sizes of paracetamol and salicylates on self poisoning in the United Kingdom: before and after study. BMJ 2001;322:1203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J, Cooper J, Johnston A, Waters K, et al. UK legislation on analgesic packs: Before and after study of long term effect on poisonings. BMJ 2004;329:1076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prince MI, Thomas SHL, James OFW, Hudson M. Reduction in incidence of severe paracetamol poisoning. Lancet 2000;355:2047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkins LC, Edwards JN, Dargan PI. Impact of restricting paracetamol pack sizes on paracetamol poisoning in the United Kingdom: A review of the literature. Drug Saf 2007;30:465-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bateman DN. Limiting paracetamol pack size: has it worked in the UK? Clin Toxicol 2009;47:536-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan OW, Griffiths C, Majeed A. Interrupted time-series analysis of regulations to reduce paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning. PLoS Med 2007;4:e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckley NA, Gunnell D. Does restricting pack size of paracetamol (acetaminophen) reduce suicides? PLoS Med 2007;4:612-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan O, Griffiths C, Majeed A. Impact of paracetamol pack size restrictions on poisoning from paracetamol in England and Wales: an observational study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bateman DN, Gorman DR, Bain M, Inglis JHC, House FR, Murphy D. Legislation restricting paracetamol sales and patterns of self-harm and death from paracetamol-containing preparations in Scotland. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:573-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheen CL, Dillon JF, Bateman DN, Simpson KJ, MacDonald TM. Paracetamol pack size restriction: the impact on paracetamol poisoning and over-the-counter supply of paracetamol, aspirin and ibuprofen. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002;11 329-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Linsley KR, Schapira K, Kelly TP. Open verdict v suicide—importance to research. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlton J, Kelly S, Dunnell K, Evans B, Jenkins R. Suicide deaths in England and Wales: trends in factors associated with suicide deaths. Popul Trends 1993;71:34-42. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawton K, Bergen H, Simkin S, Wells C, Kapur N, Gunnell D. Six-year follow-up of impact of co-proxamol withdrawal in England and Wales on prescribing and deaths: time-series study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramsay CR, Matowe L, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: Lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2003;19:613-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stata Corporation. Stata statistical software: release 10. Stata, 2007.

- 30.Neuberger J, Gimson A, Davies M, Akyol M, O’Grady J, Burroughs A, et al. Selection of patients for liver transplantation and allocation of donated livers in the UK. Gut 2008;57:252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernal W, Auzinger G, Sizer E, Wendon J. Intensive care management of acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis 2008;28:188-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, Cooper J, Kapur N. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England, 2000 to 2007. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simkin S, Hawton K, Kapur N, Gunnell D. What can be done to reduce mortality from paracetamol overdoses? A patient interview study. QJM 2012;105:41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greene SL, Dargan PI, Leman P, Jones AL. Paracetamol availability and recent changes in paracetamol poisoning: is the 1998 legislation limiting availability of paracetamol being followed? Postgrad Med J 2006;82:520-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings. 2011. www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm239894.htm.

- 36.Gottlieb S. Warnings issued over COX 2 inhibitors in US and UK. BMJ 2005;330:9.4.15626793 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang F, Wagner A, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Estimating confidence intervals around relative changes in outcomes in segmented regression analyses of time series data. 2002. www.nesug.info/Proceedings/nesug02/st/st005.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.