Abstract

The increased mortality in prostate cancer is usually the result of metastatic progression of the disease from the organ-confined location. Among the major events in this progression cascade are increased cell migration and loss of adhesion. Moreover, elevated levels of nitric oxide (NO) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) found within the tumor microenvironment are hallmarks of progression for this cancer. To understand the role of nitrosative stress in prostate cancer progression, the effects of NO/iNOS on prostate cancer cell migration and adhesion were investigated here. Our results indicate that ectopic expression of iNOS in prostate cancer cells increased cell migration, which could be blocked by selective ITGα6- blocking antibody or iNOS-inhibitors. Furthermore, iNOS was found to cause S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 at Cys86 in prostate cancer cells. By comparing the activities of the wild-type ITGα6 with a Cys86 mutant, we showed that treatment of prostate cancer cells with NO increased ITGα6 heterodimerization with ITGβ1, but not with ITGβ4. Finally, S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 decreased its binding to laminin-β1, and reduced the adhesion of prostate cancer cells to laminin-1. In conclusion, S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 increased prostate cancer cell migration, which could be a potential mechanism of NO/iNOS–induced enhancement of prostate cancer metastasis.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer in American men (1) and will kill ~ 28,000 patients in 2012 primarily due to metastatic disease (2). To reduce mortality from this cancer, it is therefore imperative to understand how PCa cells escape the primary tumor and spread to secondary sites. A loss of cellular adhesion and an increase in cell motility are major events in this metastatic cascade.

Nitric oxide (NO), a free radical gas, has been shown to play an important role in tumor progression (3;4). It is synthesized from L-arginine by NO synthases (NOSs) (5). Three major human isoforms have been identified, namely the neuronal (n), endothelial (e), and inducible (i) NOS (6). Endothelial and neuronal NOSs are constitutively expressed and responsible for maintaining low levels (nanomolar range) of NO production in a cell-type specific manner. In contrast, the iNOS produces high output (micromolar range) of NO in response to inflammatory cytokines or pathogens as part of the host defense mechanism (6;7). At low levels, NO is a ubiquitous signaling molecule that regulates normal cellular functions (5;7) while chronic high levels of NO contribute to the development of various diseases including PCa (8-10).

In PCa, NO promotes tumor initiation and progression (9;10). Inducible NOS was found overexpressed in high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) (9) and adenocarcinoma (10), as well as in their surrounding inflammatory cells when compared with levels expressed in adjacent non-malignant tissue (11). It has been postulated that the overexpression of iNOS promotes PCa cell growth and survival, DNA damage, angiogenesis, invasiveness and metastasis during the development and progression of the cancer through increased NO production (9-12). Yet, the downstream effectors and the mode of action of NO/iNOS in prostate carcinogenesis remain to be identified.

An important means by which NO regulates cellular functions is through post-translational modification of signaling proteins at their cysteine residues via a process called S-nitrosylation (13). Site specific S-nitrosylation alters the function, stability, subcellular localization, and binding partners of its target proteins (14). Inappropriate S-nitrosylation of key regulatory proteins disrupts normal physiological function and leads to the pathogenesis of diseases (15-17).

Integrins are expressed in all epithelial cells and have diverse functions in regulating cell morphology, cell-cell interaction, and signal transduction from extracellular matrix (18). Altered expression or aberrant distribution of integrins disrupts the cell-substratum relationship, increases cell motility, and promotes progression of epithelial cancers including PCa (19). Using the biotin switch technique (BST) (20), we recently conducted a site-specific mapping of the S-nitrosoproteome in an immortalized prostate epithelial cell line NPrEC (21) and identified integrin α6 (ITGα6) as a target for S-nitrosylation at cysteines 86, 131 and 502. BST substitutes biotin for the labile and otherwise difficult to detect NO moiety making identification of S-nitrosylation more readily achievable (Ref 32: Hess DT).

In normal prostate epithelial cells, ITGα6 binds specifically to integrin β1 (ITGβ1) or ITGβ4 to form α6β4 or α6β1 integrin. These are receptors of prostate acinar laminins, allowing cell adherence to the basement membrane (19;22). However, during PCa progression, while multiple integrins including ITGβ4 are downregulated, both ITGα6 and ITGβ1, subunits of α6β1, are overexpressed in PCas and in their corresponding lymph node metastases (23;24), suggesting that ITGα6 and/or ITGβ1 expression favors PCa cell metastasis (25). This report is first to address if S-nitrosylation plays a role in regulating the function of ITGα6 in PCa progression. Here, we report that (i) ectopic expression of iNOS or treatment with a NO donor stimulates PCa cell migration through ITGα6, (ii) iNOS associates with ITGα6 and induces S-nitrosylation of the integrin, (iii) substitution of Cys86 with serine, when compared to substitution at the other two sites, most significantly affected the iNOS/NO-induced S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 in PCa cells. We further demonstrate that S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 Cys86 enhanced binding of the integrin subunit to ITGβ1, but not to ITGβ4, and diminished its adhesion to laminin-β1. These data suggest site-specific S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 is part of the mechanism underlying the iNOS/NO-mediated promotion of PCa cell migration.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 as previously described (26).

Vector Production

Plasmids expressing ITGα6 (BC136455) and iNOS (BC130283) (Thermo Fisher, Boston, MA) were cloned into pcDNA3.1/TOPO expression vector according to manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). ITGα6 was C-terminally tagged with Flag epitope (DYKDDDDK). Mutagenesis of cysteines 86 (TGC->TCC), 131 (TGT->TCT), and 502 (TGT->TCT) to serine residues (C86S, C131S and C502S) was accomplished with Stratagene QuikChange XL site directed mutagenesis (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) of pcDNA3.1/ITGα6-Flag constructs. Ectopic expression of iNOS or a control vector (LacZ) in PC-3 cells was accomplished using lentivirus constructs as previously described (27).

Cell Transfection and Infection

HEK-293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen), and PC-3 cells were transfected using Mirus TransIT®-Prostate Transfection Kit (MirusBio Corp. Madison, WI) according to manufacturer’s protocol for 24 hours unless otherwise noted. PC-3 and DU-145 cells were infected as previously described (27).

NO donor preparation, nitrite measurement and the Biotin Switch Technique - S-nitroso-L-cysteine (CysNO) and S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO) were freshly prepared as previously described (21). CysNO and GSNO were used for experiments with NO donors needed for short and long time points, respectively. The Griess/Saltzman assay was used to detect nitrite level in cell culture media according to manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen) in triplicate. The BST (20) was performed as previously described (21). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Gel Electrophoresis and Western-blot Analysis

SDS-PAGE was performed with 8% gels under non-reducing conditions in triplicate. After electrophoresis, gels were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Immobilon FL, Millipore, Billerica, MA) with a blotting cell (Invitrogen). Antibodies used were as follows: Flag (#2368, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), β-actin (A2228, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), ITGα6 (SC-6597, Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SCBT), Santa Cruz, CA), ITGβ4 (SC-6629, SCBT), iNOS (SC-651, SCBT), Laminin-β1 (SC-17810, SCBT), ITGβ1 (MAB1987Z, Millipore), and rabbit IgG (SC-2027, SCBT). The ITGα6 antibody (GoH3) blocks the interaction of ITGα6 with laminin, and was a generous gift from Dr. Arnoud Sonnenberg (28;29). For all inhibition studies, GoH3 was used at 10 μg/ml. Primary antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilutions overnight at 4°C or 1 hour followed by corresponding IRDye conjugated secondary antibodies (LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) used at 1:15,000 dilutions as previously described (21).

Wound healing

Cells were allowed to reach confluence, serum starved for 24 hours, and wounded as previously described (30) in triplicate. Specifically, cells were treated with NO donor and/or ITGα6 inhibiting antibody, GoH3 at indicated doses. Pictures were taken at 0, 8, or 24 hours using a Zeiss microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, GmbH, Germany) at 40X magnification. Migratory distances were measured using Zeiss Axiovision software. Wells were coated overnight at 10 μg/ml laminin-1 and fibronectin (Sigma Aldrich) at 4°C. For the antibody inhibition experiments all antibodies were used at 10 μg/ml. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Boyden Chamber Assay

Cell invasion was measured using the Boyden chamber assay (BD Biosciences, Raleigh, NC) as previously described (30) with the following modifications. Invasion chambers were coated with 10 μg/ml human laminin-1 (Sigma Aldrich) overnight at room temperature followed by blocking 0.1% BSA/PBS prior to seeding cells.

Cell Viability

Cell viability was measured using the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) reagent and diluting (1:5) in cell media and incubating 1 hour after the experiment. Viable cells were determined colorimetrically by setting the absorbance at 490 nm directly proportional to the number of living cells in culture.

BrDU Incorporation

DNA synthesis was measured according to manufacturer’s protocol (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Cell Adherence

Cell adhesion experiments were performed as previously described (29) in triplicate. Specifically, wells were coated with 10 μg/ml human laminin-1 (Sigma Aldrich) followed by blocking with 0.5% BSA/PBS. Wells were washed with 0.1% BSA/PBS prior to seeding 40,000 cells. Cells were allowed to adhere for 1 hour at 37°C. Non-adherent cells were aspirated and wells were washed with rotation at 70 rpm four times. Adherent cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Plates were washed followed by methanol incubation. Adherent cells were stained with crystal violet and read spectrophotometrically at 490 nm. Cells adherence was calculated as the ratio of cells adhered to laminin-1 to those adhered to poly-lysine. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Lysates were co-immunoprecipitated according to a published protocol (31). Specifically, cells were seeded on plates coated with 10 μg/ml laminin-1 and lysed with radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma Aldrich) with protease inhibitors. Lysates were incubated with 2 μg/ml primary or control antibodies for 16 hours at 4°C. The primary antibodies were pulled down with protein A/G Plus agarose beads (SC-651 SCBT). Laminin-β1 was chosen for laminin-1 coimmunoprecipitation because it is known to interact with ITGα6 (28). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were calculated using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). ImageJ software for quantification of band intensity on a Western blot was downloaded from http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html.

RESULTS

NO/iNOS Stimulates PCa Cell Migration via ITGα6 Action

To determine whether S-nitrosylation plays a role in regulating the function of ITGα6 in PCa progression, we tested whether increased NO/iNOS contents enhance PCa cell migration and invasion, key events in cancer progression. To do this, we first determined the concentration of nitroso-glutathione (GSNO) tolerated by PC-3 cells by measuring the effect of increasing GSNO concentrations on PC-3 cell viability (Fig. 1A). Since, the 100 μM GSNO dose was well tolerated; we tested its effect upon cell invasion using Boyden chambers coated with laminin-1. In the presence of the 100 μM GSNO dose, there was a significant increase in cell invasion (Fig. 1B). Cell invasion is thought to result from changes in two cellular functions: remodeling of the cellular adhesion interactions both with adjoining cells and with the extracellular matrix, and cell migration. To confirm the effects of GSNO on cell migration, we used the in vitro wound healing assay. Moreover, since high levels of NO in the prostate tumor microenvironment has been attributed to high levels of iNOS in HGPIN (9), adenocarcinoma (10), and invading inflammatory cells (11), we either treated the two PCa cell lines, PC-3 and DU-145, with GSNO, or transfected them with an iNOS expression plasmid (Fig. 1F). 24 hours post-wounding, a significant increase in migration was observed in these cell lines after treatment with GSNO, when compared with their respective untreated controls (Fig. 1C). Additionally, iNOS expression resulted in a statistically significant, increased cell migration compared to the empty vector controls (Fig. 1C, lower panels EV and iNOS). To confirm ectopic expression of iNOS increased NO production, the levels of nitrite were measured in cell culture media at the end of the wound healing assay (Supplemental Fig. 1A & 1B). A significant increase in the levels of measurable nitrite was observed in PCa cell cultures 24 hours after transfection with the iNOS-expression-plasmid (Supplemental Fig. 1C) even with a transfection rate of 40-60% (not shown). The nitrite levels in the culture media from these cells were comparable to those obtained from cells treated with 100 μM GSNO. Furthermore, elevated levels of NO persisted for at least 48 hours after either treatment (Supplemental Fig. 1C). A weakness of the wound healing assay is that the observed cell migration could be a result of cell proliferation. We hence checked that the observed increase in cell migration was not an artifact of an enhancement of cell proliferation. Neither GSNO nor ectopic iNOS expression altered cell viability in the treated cultures (Fig. 1D). Using a range of nitro-cysteine concentrations, DNA synthesis was only significantly altered at higher concentrations and not at a 100 μM CysNO dose (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

iNOS increases the migration of prostate cancer cells. (A) PC-3 cells were treated with a range of GSNO (0, 100, 250 and 500 μM) for 24 hours. (B) PC-3 cells treated with -/+ 100 μM GSNO for 24 hours were subjected to the invasion assay. (**) represents p<0.01. (C) PC-3 (left) and DU-145 (right) cells were subjected to the wound healing assay -/+ 100 μM GSNO, empty vector (EV) or iNOS expressing vector. (D) PC-3 and DU-145 cells were treated with -/+ 100 μM GSNO, and transfected with EV or iNOS for 24 hours followed by MTS cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI). (E) PC-3 cells were treated with a range of CysNO (0, 50, 100, 200 and 400 μM) for 24 hours followed by analysis of BrDU DNA synthesis assay (Millipore, Billerica, MA). (F) Western blot showing iNOS transfection efficiency (MirusBio Corp. Madison, WI) after 24 hour transfection, 100 μg loaded on an 8% gel. All experiments were done three times, except for invasion assay (n=2). (*) represents p<0.05.

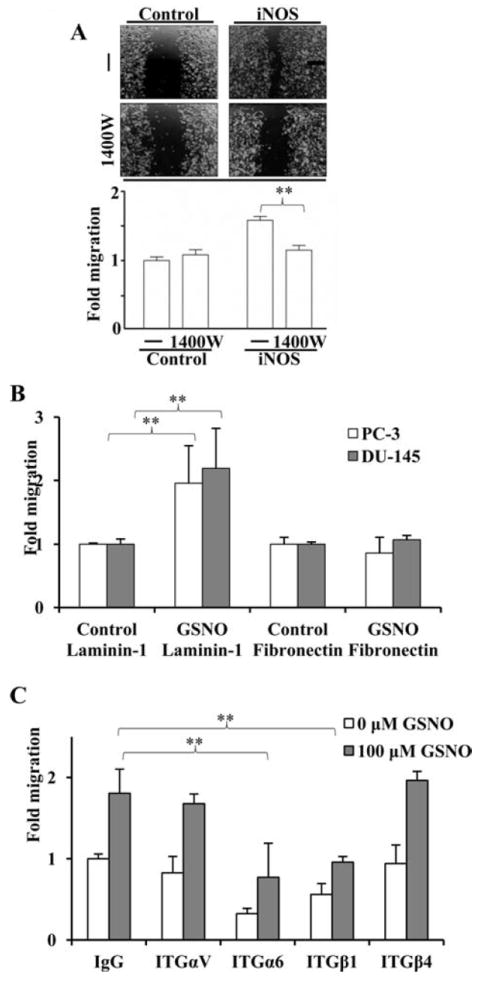

To demonstrate enhanced expression of iNOS is causally linked to increased cell migration, the wound healing assay was performed in PC-3 cultures transfected with a control or iNOS-expressing plasmid in the presence or absence of an iNOS inhibitor, 1400W. We found that iNOS-mediated enhancement of cell migration in PC-3 cells 8 hours after wounding was ameliorated upon treatment with 1400W (Fig. 2A). To test the hypothesis that NO induces PCa cell migration through integrin action per se, the wound healing assay was performed with PC-3 and DU-145 cultures treated with GSNO in wells coated with two different extracellular matrices, laminin-1 and fibronectin. GSNO increased PC-3 and DU-145 cells migration upon laminin-1 but not fibronectin (Fig. 2B). To determine which integrin was influencing prostate cancer cell migration upon laminin-1 in the presence of GSNO, the wound healing assay was performed in the presence or absence of antibodies targeted against integrins αV, α6, β1 and β4. The integrins α6 and β1 antibodies were the only ones which affected cell migration of PC3 cells (Fig. 2C, white bars). Moreover, the antibodies against α6 and β1 were found to block the GSNO-mediated enhancement of cell migration in these cultures (Fig. 2C). The increase in migration seen in the presence of GSNO is not statistically significant for the integrins α6 and β1 antibodies (Fig. 2C, gray bars).

Figure 2.

iNOS- and NO-mediated cell migration is blocked by 1400W or GoH3, respectively. (A) PC-3 cultures infected with LacZ (control) or an iNOS-expression plasmid were wounded in the absence or presence (-/+) of 100 μM 1400W for 8 hours. (B) PC-3 and DU-145 cells were wounded upon laminin-1 or fibronectin (10 μg/ml, each) coated plates in the absence or presence (Control or GSNO) of 100 μM GSNO for 8 hours. (C) PC-3 cells were wounded and treated in absence (white bars) or presence (grey bars) of 100 μM GSNO and incubated with anti-ITGαV, ITGα6, ITGβ1, and ITGβ4 antibodies for 8 hours. IgG was used as an isotype control. All experiments were done three times. (**) represents p<0.01.

ITGα6 Interacts with iNOS and is S-nitrosylated by Increased Levels of NO or iNOS Expression

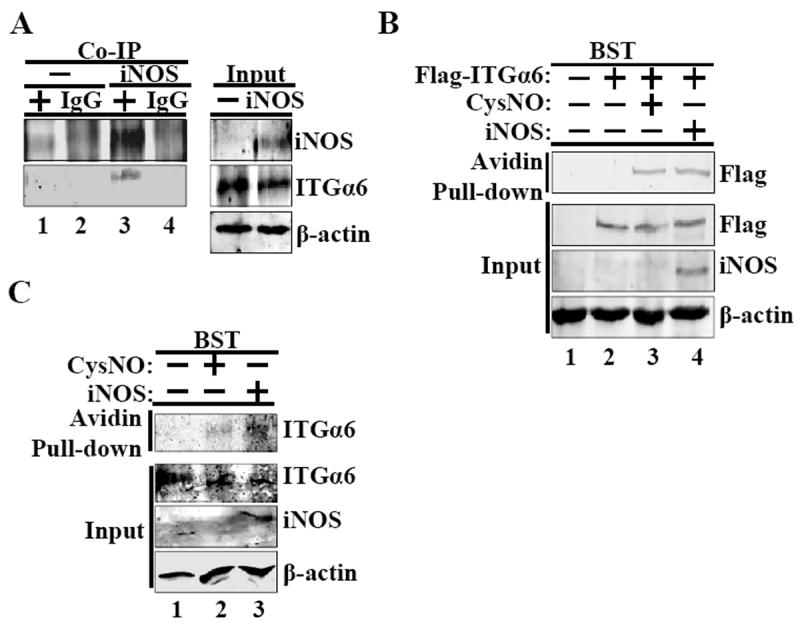

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were carried out to examine whether iNOS associates with ITGα6. Cell lysates from PC-3 cells infected with the iNOS-expression virus or LacZ-expression virus were immunoprecipitated with anti-iNOS, anti-ITGα6, or IgG control antibodies and subjected to western blot analysis. ITGα6 was found to co-immunoprecipitate with iNOS (Fig. 3A, lane 3), suggesting the possibility of an association between these two proteins. To determine whether iNOS S-nitrosylates ITGα6, HEK-293 cells transiently transfected with a control or ITGα6-Flag-expression plasmid were subjected to the BST in the presence or absence of the NO donor CysNO or following the transfection of an iNOS-expression plasmid. Western blot analyses revealed that S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 occurred in the presence of CysNO or ectopic expression of iNOS (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4), but not in their absence (lane 2). To demonstrate endogenous ITGα6 can be S-nitrosylated in PCa cells, PC-3 cells were infected with the iNOS-expression virus or treated with CysNO, and subjected to the BST (Fig. 3C). S-nitrosylated ITGα6 was detected only in PC-3 cells treated with the NO donor or ectopically expressing iNOS (Fig. 3C, lane 2, 3), but not in control PC-3 cells (lane 1). ITGα6 was also S-nitrosylated in LNCaP and DU-145 cells (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

ITGα6 interacts with iNOS and is S-nitrosylated with increased NO or iNOS expression in cellullo. (A) iNOS was coimmunoprecipitated (Co-IP) with ITGα6 using from PC-3 lysates infected with LacZ (-) or the iNOS-expression plasmid. (+) indicates iNOS antibody immunoprecipitation. (B) The BST was conducted using lysates from HEK-293 transfected with or without an ITGα6-Flag plasmid following treatment with 1mM CysNO or transfected with an iNOS-expression plasmid (iNOS). (C) The BST was carried out in PC-3 cells with or without treatment with 1mM CysNO or transfection of an iNOS-expression plasmid. All experiments were done three times.

Cys86 is Central in ITGα6 S-nitrosylation

We previously reported treatment of NPrEC with CysNO induced S-nitrosylation of 172 proteins (21). ITGα6 was identified to be in this S-nitrosoproteome and the S-nitrosylation shown to occur at Cys86, Cys131 and Cys502 by mass-spectrometry (21). As indicated in the cartoon of ITGα6, these sites are located on the extracellular head (Cys86 and 131) and thigh (Cys502) regions of ITGα6 (Fig. 4A). To determine which of these three cysteines is the most important site mediating ITGα6 S-nitrosylation, PC-3 cells stably expressing the empty vector (PC-3/EV), wild-type ITGα6-Flag (PC-3/WT), or ITGα6-Flag with a C86S (PC-3/C86S), C131S (PC-3/C131S) or C502S (PC-3/C502S) substitution were generated These cell lines were treated with CysNO and subjected to BST analysis (Fig. 4B, upper panel). We observed a marked decrease in S-nitrosylated ITGα6 (Flag-pull down) only in PC-3/C86S (Fig. 4C, lane 3) but not in PC-3/C131S or in PC-3/C502S (Fig. 4C, lane 4 and 5). These results indicate that biochemically, Cys86 is the most important site mediating S-nitrosylation of ITGα6. To demonstrate the physiological significance of Cys86 in S-nitrosylation of ITGα6, PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells were transfected with the iNOS-expression plasmid and subjected to BST analysis (Fig 4C). No S-nitrosylated ITGα6/C86S protein was pulled down by avidin in the PC-3/C86S cell line whereas ITGα6 protein was readily detected in PC-3/WT suggesting that the Cys86 residue is important for ITGα6 S-nitrosylation by iNOS.

Figure 4.

iNOS S-nitrosylates ITGα6 at Cys86. (A) Cartoon model of ITGα6 indicating S-nitrosylation sites relative to homologous repeat domains I-VII in grey and transmembrane domain in dark grey. (B) PC-3 cells stably expressing ITGα6-Flag with cysteines 86, 131, and 502 mutated to serines were treated with 1mM CysNO and submitted to the BST. (C) WT/PC-3 and PC-3/C86S cells were transfected with the iNOS-expression plasmid and submitted to the BST. (D) ITGα6 was modeled using ITGαV crystal structure (PDB: 3IJE) to visualize S-nitrosylated Cys86, 131 and 502 (red) with their predicted cysteine binding partners (magenta) within the “head” and “thigh” tertiary domains of ITGα6. All experiments were done three times.

We next conducted the wound healing assay on PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells with or without treatment with GSNO, and in the presence and absence of anti- ITGα6 GoH3 antibody, that blocks the interaction of integrin with laminin (28). The antibody was found to block the NO-induced enhancement of cell migration in PC-3/WT cells, but not in PC-3/C86S cells (Supplemental Figure 3A).

To visualize how site-specific S-nitrosylation may affect the function of ITGα6, the tertiary structure of the protein including the three S-nitrosylation sites were modeled (Fig. 4D) using the available crystal structure of ITGαV which shares significant similarity in its primary sequence with that of ITGα6. The S-nitrosylated cysteine residues Cys86, Cys131 and Cys502 are conserved in ITGαV cysteines and their positions are shown in red with their predicted cysteine binding partners shown in magenta in Fig. 4D. While Cys86 and Cys131 are found located within the head region of ITGα6, Cys502 is located within the thigh region. Based on structural analysis, the Cys86-Cys95 loop located within the head region is largely exposed to the solvent, suggesting that Cys86 could be transiently exposed on the surface of ITGα6. Approximate normal mode analysis performed using Elastic Network Model, as implemented in the NOMAD-ref server (http://lorentz.immstr.pasteur.fr/nomad-ref.php), lends further support to the idea that the Cys86 residue contributes significantly to slow coordinated motions in ITGα6 (data not shown). Taken together, experimental and modeling results indicate that S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 at Cys86 may have significant functional relevance. Hence, subsequent functional studies were performed using PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells.

ITGα6 Cys86 is required for the NO-induced Increase in PC-3 Cell Migration and Enhanced Association with ITGβ1

To determine the consequence of a C86S substitution on NO-induced enhancement of cell migration, wound healing assays were performed with ITGα6 PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells treated with GSNO or the vehicle control (Fig. 5A). As shown previously (Fig. 1A), NO significantly increased migration of PC-3/WT cells but not that of PC-3/C86S (Fig. 5A) cells.

Figure 5.

NO mediates migration through ITGα6 Cys86 and promotes increased ITGβ1 heterodimerization. (A) PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells were wounded for 8 hours -/+ 100 μM GSNO. (*) represents p<0.05. (B) PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells were seeded onto plates pre-coated with 10 μg/ml laminin-1 and allowed to adhere for 8 hours with -/+ 100 μM GSNO. ITGα6 was immunoprecipitated using a Flag antibody and its associated ITGβ1 or ITGβ4 was detected by western blotting. Quantitation was done with ImageJ software by measuring ITGβ1 bands and subtracting from WT and C86S Flag immunoprecipitation bands. WT Flag/ITGβ1 without NO bands was set to baseline. (C) PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells were seeded onto Boyden chambers coated with 10 μg/ml laminin-1 and allowed to invade for 8 hours with -/+ 100 μM GSNO. (**) represents p<0.01. All experiments were done three times, except for invasion assay (n=2).

We then examined the effects of NO on the association of ITGα6 with ITGβ1 or ITGβ4, and determined whether the process involves Cys86. PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells were seeded onto laminin-1-coated plates and treated with GSNO for 8 hours. Lysates obtained from PC-3/WT had more ITGα6-associated ITGβ1 following GSNO-treatment when compared to levels in lysates from vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 5B, lane 1 versus lane 3, upper panel; histograms). This difference cannot be completely accounted for by the NO-induced increase in ITGα6 expression (lane1 versus lane 3 bottom panel). In contrast, GSNO-treatment did not affect the amount of ITGβ4 associated with ITGα6 (lane 1 versus lane 3, middle panel). Importantly, the amount of ITGα6, and the degree of ITGβ1 association with ITGα6 in PC-3/C86S cells were insensitive to GSNO-treatment (lane 5 versus lane 7, upper, middle and bottom panel).

To determine the effect of the Cys86 substitution, the invasion assay was performed ITGα6 PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells treated with GSNO or the vehicle control. After 24 hours, there was a significant increase in PC-3/WT cell invasion but not for PC-3/C86S cells (Fig. 5C).

S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 at Cys86 mediates the NO-induced reduction in cell adherence to laminin-1. We examined the effect of NO on ITGα6-mediated cell adhesion to laminin-1 which is composed of α1, β1, and γ1 subunits and its other nomenclature is laminin-111. PC-3/WT and PC-3/C86S cells were seeded on laminin-1 coated plates in the presence or absence of GSNO for 1 hour. Treatment with GSNO caused a significant decrease in cell adherence in PC-3/WT but exerted no effect on the adherence of PC-3/C86S to laminin-β1 (Fig. 6A). GSNO treatment did not cause a significant alteration of PC-3 cell adhesion to poly-lysine alone (Supplemental Fig. 3B). In concordance, while treatment of PC-3/WT cells with GSNO reduced ITGα6-laminin-1 interaction (Fig. 6B, lane 1 versus 2) it has no effects on the PC-3/C86S cell line (lane 3 versus 4), as demonstrated in experiments using Flag-ITGα6 immuno-precipitation followed by Western blotting for laminin-β1. These results indicate that the disruption of cell adhesion after GSNO treatment is attended by a reduction in ITGα6-laminin-β1 interaction, with both processes likely mediated by S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 at Cys86.

Figure 6.

Cys86 is responsible for NO destabilization of ITGα6-mediated cell adherence. (A) WT/PC-3 and C86S cells were seeded onto plates pre-coated with human laminin-1 or poly-lysine and allowed to adhere for 1 hour in the presence or absence of 500 μM GSNO. % Cell adherence was calculated as cell absorbance on laminin-1 divided by absorbance on poly-lysine × 100% with values observed in untreated WT/PC-3 arbitrarily set as 100%. (*) represents p<0.05. (B) WT/PCS and C86S/PC-3 cells adhered to laminin-1 for 1 hour in the presence 500 μM GSNO were used to prepare cell lysates for immunoprecipitation with Flag-antibody. Laminin-β1 was chosen for laminin-1 coimmunoprecipitation because it is known to mediate interactions with ITGα6. Quantitation of WT and C86S Flag IP bands relative to their laminin-β1 bands was done with ImageJ software. All experiments were done three times.

DISCUSSION

Integrins are important mediators of cell adhesion and migration (18). In this study, we showed that NO and iNOS significantly increased PCa cell migration and decreased cell adhesion through S-nitrosylation of Cys86 on ITGα6. This post-translational modification was further showed to promote the interaction of ITGα6 with ITGβ1, but not ITGβ4, and diminish its association with laminin-β1. These findings are consistent with reports demonstrating a positive association between iNOS expression and PCa progression and metastasis in clinical specimens (9-11) and the pivotal role of perturbations of cancer cell-matrix interaction in PCa progression (32).

Our findings provide the first evidence that S-nitrosylation of an integrin (ITGα6) promotes PCa cell migration in a site-specific manner. Although earlier studies have reported NO promotes cell migration in a variety of cells such as eosinophils (33) and mammary cancer cells (34) few have definitively demonstrated S-nitrosylation of motility-related molecules at specific cysteines as a causative factor. This initial lack of progress was in part due to the very unstable nature of the S-nitrosylated proteins. With the development of the BST, the highly unstable protein-SNOs are replaced with biotin that can be readily detected, as well as be sequenced for the identification of the S-nitrosylation sites (20;35). Using BST, S-nitrosylation of actin in neutrophils was shown to alter actin polymerization, network formation, intracellular distribution and interaction with integrins (36). Similarly, both NO and estradiol-17β activates c-Src through S-nitrosylation of its Cys498 in MCF-7 cells and promotes cancer cell invasion and metastasis (37).

Our data suggest iNOS may directly interact with ITGα6 and mediate S-nitrosylation of the integrin. In fact, overexpression of iNOS is more effective than GSNO presumably because iNOS can directly interact with ITGα6 and therefore directly S-nitrosylate ITGα6. This postulate is consistent with the general belief that the selectivity of S-nitrosylation is provided by protein-protein interaction such as that of the S-nitrosylation of cyclooxygenase-2 (38) and caspase-3 (39). However, since Cys86, identified to be essential for S-nitrosylation, is located in the head region that normally resides outside the cell membrane, it raises the question of how intracellular iNOS can S-nitrosylate this site. One probable mechanism is through the individual association of iNOS (40) and integrins (41) with caveolin-1, bringing these two molecules to the caveolae, the plasma membrane organelle responsible for recycling integrins and transducing matrix information during cell migration (42). Whether iNOS-induced S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 occurs within the caveolae remains to be established. Alternatively, it is possible that the NO released by intracellular iNOS diffuses across the cell membrane and S-nitrosylates ITGα6 on the outside of the cell.

From modeling ITGα6, we recognize that Cys86 lies at the bottom of an easily exposed loop and, in contrast, Cys131 is fully buried. Therefore the S-nitrosylation of Cys86 might lead to exposure of Cys131 and its subsequent S-nitrosylation. So in the absence of Cys86 S-nitrosylation, Cys131 may not be accessible for S-nitrosylation. In this regard, Cys86 may be the first in a cascade of S-nitrosylation of a series of cysteines including Cys131 Cys502, analogous to the sequential phosphorylation of multiple sites at the cytoplasmic tails of receptor tyrosine kinases (43). Thus in silico predictions could explain the experimental observation that Cys86 is the most sensitive S-nitrosylation site on ITGα6. However, future investigations are needed to ascertain whether sequential or cooperative S-nitrosylation of multiple cysteines in ITGα6 partakes in the regulation of the action of this integrin.

S-nitrosylation of Cys86 on ITGα6 was found to be essential and sufficient to mediate the NO/iNOS-induced enhancement of PCa cell migration and loss of matrix adhesion. These results are consistent with findings from a series of studies reporting NO regulates the disulfide bonds in extracellular proteins including integrins (44-46). S-nitrosylation of specific cysteines in integrins induces breakage, reformation or reshuffling of disulfide bonds resulting in conformational changes in these molecules (47). These changes ultimately lead to functional changes including alterations of ligand-binding/matrix-adhesion and cell motility for these integrins (48;49). Such structural and functional changes probably occur upon S-nitrosylation of Cys86 on ITGα6, resulting in decreased cell adhesion and increased cell migration.

At the molecular level, we showed that S-nitrosylation of Cys86 favors the association of ITGα6 with ITGβ1 (and not ITGβ4) and reduces its binding to laminin-1/laminin-β1. We suggest that NO is increasing its interaction with ITGβ1 and we showed that ITGβ4 heterodimerization remains the same. These findings are in agreement with previous studies (22) reporting increased production/formation of integrin α6β1 and laminin as promoters of tumor progression and metastasis that is commonly attended with a loss of α6β4. One probable mechanism underlying the S-nitrosylation-induced alterations in heterodimer preference and matrix protein-affinity could be the result of breaking/reshuffling of disulfide bonds at targeted cysteines as discussed above. Another likely mechanism may involve the cleavage of ITGα6 at Arg594, 595 that has previously been shown to play a significant role in PCa migration and metastasis (50). However, although Cys502 is in close proximity to Arg594, 595, it remains to be determined if S-nitrosylation of this site mediates or facilitates ITGα6 cleavage.

In conclusion, iNOS induced increased migration of PCa cells via S-nitrosylation of ITGα6 at Cys86 that is likely the trigger of enhanced ITGα6-ITGβ1 heterodimerization and loss of ITGα6 binding to laminin-β1. These biochemical and molecular changes were accompanied by decreased cell adherence and increased motility in PCa cells. A schematic model has been proposed (Fig. 7). Given these observations, inhibiting S-nitrosylation has potential for use in prostate cancer therapy and prevention.

Figure 7.

Proposed model of how iNOS may affect ITGα6 binding to Laminin-1 and heterodimerization to ITGβ4 and ITGβ1 resulting in decreased adherence and increased cell migration.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Nitrite increases in cell medium after iNOS transfection.

Supplemental Figure 2. ITGα6 is S-nitrosylated in LNCaP and DU-145 cells.

Supplemental Figure 3. GoH3 does not block cell migration of PC-3/C86S cells in the presence of 100 μM GSNO.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Arnoud Sonnenberg, PhD from the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Department Cell Biology who graciously provided GoH3 antibody and Jarek Meller, PhD, from the University of Cincinnati, Division of Biomedical Informatics for the modeling studies of ITGα6.

Funding Sources

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grant #ES006096 (SH), the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program Department of Defense award # PC10835 (JI), and award #PC094619 (PT).

Abbreviations

- NO

nitric oxide

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- ITGα6

integrin alpha 6

- ITGβ4

integrin beta 4

- ITGβ1

integrin beta 1

- BST

biotin switch technique

Footnotes

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lala PK, Chakraborty C. Role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis and tumour progression. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomsen LL, Miles DW. Role of nitric oxide in tumour progression: lessons from human tumours. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1998;17:107–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005912906436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moncada S, Higgs A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Ruiz A, Cadenas S, Lamas S. Nitric oxide signaling: classical, less classical, and nonclassical mechanisms. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu W, Liu LZ, Loizidou M, Ahmed M, Charles IG. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell Res. 2002;12:311–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baltaci S, Orhan D, Gogus C, Turkolmez K, Tulunay O, Gogus O. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in benign prostatic hyperplasia, low- and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic carcinoma. BJU Int. 2001;88:100–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaltoma SH, Lipponen PK, Kosma VM. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and its prognostic value in prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3101–3106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uotila P, Valve E, Martikainen P, Nevalainen M, Nurmi M, Harkonen P. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase-2 in human prostate cancer. Urol Res. 2001;29:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s002400000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanella L, Di GC, Acquaviva R, Santangelo R, Cardile V, Barbagallo I, Abraham NG, Sorrenti V. The DDAH/NOS pathway in human prostatic cancer cell lines: antiangiogenic effect of L-NAME. Int J Oncol. 2011;39:1303–1310. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess DT, Stamler JS. Regulation by S-nitrosylation of protein post-translational modification. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4411–4418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.285742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura T, Lipton SA. Redox modulation by S-nitrosylation contributes to protein misfolding, mitochondrial dynamics, and neuronal synaptic damage in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1478–1486. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uehara T, Nakamura T, Yao D, Shi ZQ, Gu Z, Ma Y, Masliah E, Nomura Y, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylated protein-disulphide isomerase links protein misfolding to neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;441:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature04782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaston B, Sears S, Woods J, Hunt J, Ponaman M, McMahon T, Stamler JS. Bronchodilator S-nitrosothiol deficiency in asthmatic respiratory failure. Lancet. 1998;351:1317–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung KK, Thomas B, Li X, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Marsh L, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin’s protective function. Science. 2004;304:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.1093891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Flier A, Sonnenberg A. Function and interactions of integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;305:285–298. doi: 10.1007/s004410100417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goel HL, Li J, Kogan S, Languino LR. Integrins in prostate cancer progression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:657–664. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam YW, Yuan Y, Isaac J, Babu CV, Meller J, Ho SM. Comprehensive identification and modified-site mapping of S-nitrosylated targets in prostate epithelial cells. PLoS One 5. 2010:e9075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cress AE, Rabinovitz I, Zhu W, Nagle RB. The alpha 6 beta 1 and alpha 6 beta 4 integrins in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1995;14:219–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00690293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonkhoff H, Stein U, Remberger K. Differential expression of alpha 6 and alpha 2 very late antigen integrins in the normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic prostate: simultaneous demonstration of cell surface receptors and their extracellular ligands. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90033-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knox JD, Cress AE, Clark V, Manriquez L, Affinito KS, Dalkin BL, Nagle RB. Differential expression of extracellular matrix molecules and the alpha 6-integrins in the normal and neoplastic prostate. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:167–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabinovitz I, Nagle RB, Cress AE. Integrin alpha 6 expression in human prostate carcinoma cells is associated with a migratory and invasive phenotype in vitro and in vivo. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1995;13:481–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00118187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung YK, Mak P, Hassan S, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta isoforms: a key to understanding ER-beta signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13162–13167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung YK, Lam HM, Wu S, Song D, Levin L, Cheng L, Wu CL, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor beta2 and beta5 are associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer, and promote cancer cell migration and invasion. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:675–689. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aumailley M, Timpl R, Sonnenberg A. Antibody to integrin alpha 6 subunit specifically inhibits cell-binding to laminin fragment 8. Exp Cell Res. 1990;188:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90277-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonnenberg A, Linders CJ, Modderman PW, Damsky CH, Aumailley M, Timpl R. Integrin recognition of different cell-binding fragments of laminin (P1, E3, E8) and evidence that alpha 6 beta 1 but not alpha 6 beta 4 functions as a major receptor for fragment E8. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:2145–2155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam HM, Suresh Babu CV, Wang J, Yuan Y, Lam YW, Ho SM, Leung YK. Phosphorylation of human estrogen receptor-beta at serine 105 inhibits breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann M, Klar S, Wilisch-Neumann A, Hollenbach E, Kavuri S, Leverkus M, Kandolf R, Brunner-Weinzierl MC, Klingel K. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is a crucial mediator of signal-induced RelB degradation. Oncogene. 2011;30:2485–2492. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung LW, Baseman A, Assikis V, Zhau HE. Molecular insights into prostate cancer progression: the missing link of tumor microenvironment. J Urol. 2005;173:10–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141582.15218.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomazzi SM, Ferreira HH, Conran N, De NG, Antunes E. Role of nitric oxide on in vitro human eosinophil migration. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:1417–1421. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orucevic A, Bechberger J, Green AM, Shapiro RA, Billiar TR, Lala PK. Nitric-oxide production by murine mammary adenocarcinoma cells promotes tumor-cell invasiveness. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:889–896. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990611)81:6<889::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Mancini DJ, Milovanova TN. Actin S-nitrosylation inhibits neutrophil beta2 integrin function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10822–10834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman MA, Senga T, Ito S, Hyodo T, Hasegawa H, Hamaguchi M. S-nitrosylation at cysteine 498 of c-Src tyrosine kinase regulates nitric oxide-mediated cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3806–3814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SF, Huri DA, Snyder SH. Inducible nitric oxide synthase binds, S-nitrosylates, and activates cyclooxygenase-2. Science. 2005;310:1966–1970. doi: 10.1126/science.1119407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felley-Bosco E, Bender F, Quest AF. Caveolin-1-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in human colon carcinoma cells. Biol Res. 2002;35:169–176. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602002000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Echarri A, Muriel O, Del Pozo MA. Intracellular trafficking of raft/caveolae domains: insights from integrin signaling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:627–637. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salanueva IJ, Cerezo A, Guadamillas MC, Del Pozo MA. Integrin regulation of caveolin function. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:969–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Gutkind JS, Yamada KM. Integrins can collaborate with growth factors for phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases and MAP kinase activation: roles of integrin aggregation and occupancy of receptors. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1633–1642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahamed J, Versteeg HH, Kerver M, Chen VM, Mueller BM, Hogg PJ, Ruf W. Disulfide isomerization switches tissue factor from coagulation to cell signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13932–13937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606411103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stathakis P, Fitzgerald M, Matthias LJ, Chesterman CN, Hogg PJ. Generation of angiostatin by reduction and proteolysis of plasmin. Catalysis by a plasmin reductase secreted by cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20641–20645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lahav J, Gofer-Dadosh N, Luboshitz J, Hess O, Shaklai M. Protein disulfide isomerase mediates integrin-dependent adhesion. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walsh GM, Leane D, Moran N, Keyes TE, Forster RJ, Kenny D, O’Neill S. S-Nitrosylation of platelet alphaIIbbeta3 as revealed by Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6429–6436. doi: 10.1021/bi0620712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walsh GM, Sheehan D, Kinsella A, Moran N, O’Neill S. Redox modulation of integrin [correction of integin] alpha IIb beta 3 involves a novel allosteric regulation of its thiol isomerase activity. Biochemistry. 2004;43:473–480. doi: 10.1021/bi0354536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lahav J, Wijnen EM, Hess O, Hamaia SW, Griffiths D, Makris M, Knight CG, Essex DW, Farndale RW. Enzymatically catalyzed disulfide exchange is required for platelet adhesion to collagen via integrin alpha2beta1. Blood. 2003;102:2085–2092. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King TE, Pawar SC, Majuta L, Sroka IC, Wynn D, Demetriou MC, Nagle RB, Porreca F, Cress AE. The role of alpha 6 integrin in prostate cancer migration and bone pain in a novel xenograft model. PLoS One 3. 2008:e3535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Nitrite increases in cell medium after iNOS transfection.

Supplemental Figure 2. ITGα6 is S-nitrosylated in LNCaP and DU-145 cells.

Supplemental Figure 3. GoH3 does not block cell migration of PC-3/C86S cells in the presence of 100 μM GSNO.