Abstract

Although UVA has different physical and biological targets than UVB, the contribution of UVA to skin cancer susceptibility and its molecular basis remain largely unknown. Here we show that chronic UVA radiation suppresses PTEN expression at the mRNA level. Subchronic and acute UVA radiation also down-regulated PTEN in normal human epidermal keratinocytes, skin culture and mouse skin. At the molecular level, chronic UVA radiation decreased the transcriptional activity of the PTEN promoter in a methylation-independent manner, while it had no effect on the protein stability or mRNA stability of PTEN. In contrast, we found that UVA-induced activation of the Ras/ERK/AKT and NF-κB pathways plays an important role in UV-induced PTEN down-regulation. Inhibiting ERK or AKT increases PTEN expression. Our findings may provide unique insights into PTEN down-regulation as a critical component of UVA’s molecular impact during keratinocyte transformation.

Keywords: PTEN, UVA, keratinocytes, Ras, AKT, ERK

INTRODUCTION

Non-melanoma skin cancer (skin cancer) is the most common type of cancer in the United States (US). Each year more than one million new cases of skin cancer are diagnosed in the U.S. alone, accounting for 40% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases (1, 2). The major risk factor of skin cancer is UV radiation in sunlight, including UVB (280–315 nm) and UVA (315–400 nm). UVB has long been known to cause skin cancer (3–5). Since UVA alone is less carcinogenic than UVB (6–8), UVA has been generally assumed to be safe. This has indirectly resulted in rapid growth of the tanning business using high-powered UVA lamps in developed countries (9–15) and little development of protection against UVA in sunscreens (16). However, we now know that UVA is carcinogenic in mice (17, 18). In humans, prolonged outdoor recreational sun exposure due to the use of high SPF (sun protection factor) sunscreen (19) without sufficient UVA protection (20) may lead to increased UVA damage and thus skin cancer risk. We and others have independently shown that UVA induces tumorigenic transformation of human HaCaT keratinocytes (21, 22). UVA has different physical and biological targets than UVB (23–25); UVA’s targets involve the formation of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress (26–29). UVA is more abundant than UVB in the sunlight and much more UVA penetrates the epidermis and reaches the basal germinative layers (30). Recently, UVA signature mutations have been detected in human squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and solar keratosis (15), underscoring its important role in causing skin cancer. However, the molecular basis remains largely unknown.

One of the critical factors that inhibit tumorigenesis is PTEN (31), a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT pathway (32). This ubiquitous and evolutionarily conserved signaling cascade influences many functions including cell growth, survival, proliferation, migration, and metabolism (33, 34). Our recent evidence shows that PTEN reduction exerts a critical role in UVA-induced development of Seborrheic keratoses as well as SCC (35). Our previous studies have shown that chronic UVA radiation down-regulates PTEN expression in human HaCaT keratinocytes during malignant transformation in association with acquired apoptotic resistance (21). However, the molecular mechanism by which UVA down-regulates PTEN remains unknown. In this study, we have shown that PTEN mRNA and protein levels are decreased by chronic, subchronic and acute exposure of UVA both in vitro and in vivo. UVA does not affect PTEN protein stability or mRNA stability, whereas it decreases the transcriptional activity of the PTEN promoter. However, PTEN down-regulation does not require promoter methylation. Furthermore, our results indicate that Ras-dependent activation of AKT and ERK may play an important role in UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and EpiDerm skin culture

HaCaT cells were maintained in a monolayer culture in 95% air/5% CO2 at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units per mL penicillin, and 100 mg per mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). Normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) were obtained from Clonetics (Lonza) and cultured in KGM Gold BulletKit medium (Clonetics, Lonza) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NHEK cells were cultured for fewer than 4 passages. EpiDerm skin culture (kindly provided by Dr. Patrick J. Hayden, MatTek Corporation, MA, USA) was cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

UVA radiation

UVA radiation was performed as described previously (21, 36). Our UVA radiation was monitored every other week to measure the exposure output and dose. DuPont Teijin Films (Melinex 453/400, cutoff 315 nm, DuPont) were used to remove UVB radiation.

Animal Treatments

All animal procedures have been approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. B6 mice were shaved two days prior to the first UVA treatment. Mice were exposed to UVA (15 or 30 J/cm2) dorsally or sham-irradiated, three times a week for one week. Mouse skin was collected for PTEN analysis by immunohistochemistry.

Transfection

HaCaT cells were transfected with a plasmid construct expression empty vector or dominant negative Ras (N17Ras, a kind gift from Dr. John O’Brian at the University of Illinois at Chicago) using Amaxa Nucleofector II as described in our previous studies (37, 38).

Western blotting

Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein were subjected to electrophoresis. Western blotting was performed as described previously using film detection (21, 37). Antibodies used included PTEN phospho-ERK (p-ERK), ERK, phospho-AKT ser473 (p-AKT), p65, Lamin B, β-actin, GAPDH (Santa Cruz), p-p65 ser276 (p-p65) (Cell Signaling Technology), and Ras (Upstate).

Immunohistochemistry, promoter reporter assay, real-time PCR, cytosol-nuclear fractionation and gel shift analysis

Immunohistochemical analysis of PTEN levels in the mouse epidermis was conducted in the Immunohistochemistry Core facility. The promoter reporter assay, real-time PCR analysis and cytosol-nuclear fractionation were performed as described in our recent studies (37, 38). Gel shift analysis of NF-κB activation was performed using the Gel Shift Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The oligonucleotide sequences for NF-κB are 5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′, and 3′-TCA ACT CCC CTG AAA GGG TCC G-5′.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). Data were expressed as the mean of three independent experiments and analyzed by Student’s t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

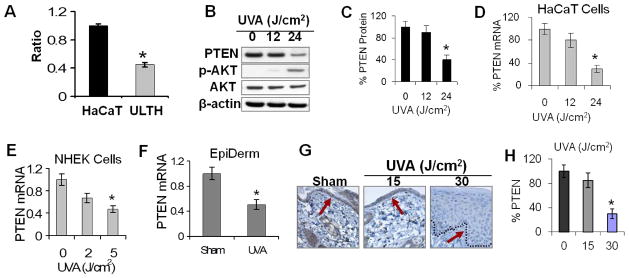

Chronic, subchronic, and acute UVA radiation decreases the mRNA and protein levels of PTEN in vitro and in vivo

To determine the molecular impact of chronic UVA radiation on keratinocytes, we used real-time PCR analysis to examine the mRNA levels of PTEN in ULTH (UVA-long-term irradiated HaCaT) cells, which were derived from chronic UVA radiation (21), and their parental control HaCaT cells. Real-time RT-PCR analysis indicates that PTEN mRNA levels were significantly reduced in ULTH cells as compared with HaCaT cells (Fig. 1A). To determine whether subchronic or acute UVA radiation affects PTEN expression, as chronic UVA radiation did, we assessed PTEN expression in sham- and UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells, normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK), skin culture, and mouse skin. When HaCaT cells were exposed to different doses of acute UVA, PTEN was significantly down-regulated at 72 hours following exposure to 24 J/cm2 UVA, but not to 12 J/cm2 UVA (Fig. 1B–C). PTEN down-regulation post-UVA was correlated with increased AKT activation, although total AKT decreased. PTEN mRNA levels were also determined in HaCaT cells at 72 hours post-UVA. In HaCaT cells, 24 J/cm2 UVA radiation significantly decreased the mRNA levels of PTEN in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1D), consistent with the alteration of PTEN protein levels. These data show that UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation is dose-dependent.

Fig. 1. Chronic, subchronic, and acute UVA radiation decreases the mRNA and protein levels of PTEN in vitro and in vivo.

A, Real-time PCR analysis of PTEN mRNA levels in HaCaT and ULTH cells. *, p < 0.05, significant difference between HaCaT and ULTH cells. B, immunoblot analysis of PTEN, phospho-AKT (p-AKT), and total AKT in sham- or UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells at 72 h post-UVA (J/cm2). β-actin blot was used as an equal-loading control. C, quantification of PTEN levels in B. D–F, real-time PCR analysis of PTEN mRNA levels at 72 h post-UVA in HaCaT cells (D), NHEK cells at 24 h after exposure to UVA (0, 2, or 5 J/cm2) once daily for four treatments (E), and EpiDerm skin culture at 24 h after exposure to UVA (6 J/cm2) or sham once daily for four treatments (F). G, immunohistochemical analysis of PTEN in sham- or UVA-irradiated mouse epidermis. Mice were exposed to UVA (0, 15, or 30 J/cm2) every other day for three treatments, and mouse skin was collected at 72 h after the final UVA exposure. The dotted line indicates the boundary between epidermis and dermis. The arrow indicated the basal keratinocyte layers for comparison of PTEN levels. H, quantification of PTEN levels in G. *, p < 0.05, significant difference between sham and UVA-irradiated cells.

To determine whether UVA-induced PTEN mRNA down-regulation is specific for HaCaT cells, we further evaluated the effect of UVA on PTEN mRNA levels in NHEK cells and EpiDerm skin culture. Similar to HaCaT cells, in NHEK cells UVA radiation decreased the expression of PTEN mRNA levels at 72 hours at 5 J/cm2 for four UVA treatments in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1E). Markedly decreased mRNA levels of PTEN were also found in EpiDerm skin culture post-UVA (6 J/cm2, four treatments) compared with sham-irradiated culture (Fig. 1F).

To further determine the effect of UVA on PTEN expression in vivo, we evaluated the effect of acute UVA radiation on PTEN levels in mouse epidermis using immunohistochemical analysis. As shown in Fig. 1G–H, UVA significantly reduced PTEN protein levels in interfollicular epidermal keratinocytes at 30 J/cm2 (P < 0.05; Student’s t-test), but not at 15 J/cm2. Taken together, these data indicate that, in addition to chronic UVA radiation, subchronic or acute UVA radiation down-regulates PTEN in vitro and in vivo.

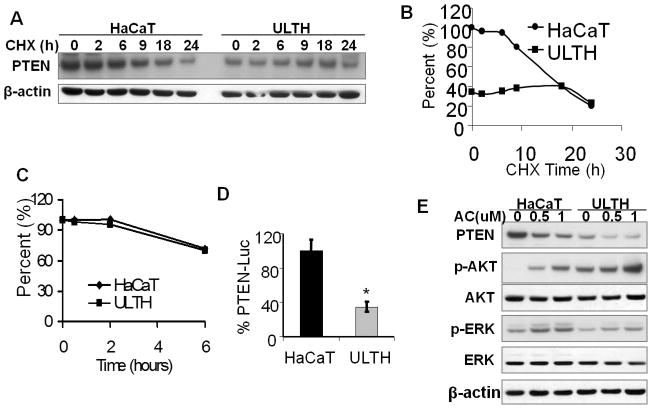

Chronic UVA radiation down-regulates PTEN transcription but has no effect on PTEN protein stability or mRNA stability

To determine the mechanism of UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation, we assessed the role of PTEN protein stability, mRNA stability, and promoter transcription. In HaCaT cells treated with cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of protein biosynthesis, PTEN levels were reduced at a nearly linear rate after 6 h (Fig. 2A–B). In ULTH cells, however, PTEN levels were sustained up to 18 h in the presence of CHX and then reduced at a rate similar to that of normal HaCaT cells (Fig. 2A–B). These data suggest that UVA-induced PTEN protein down-regulation was not due to a decrease in protein stability but may be a result of a reduction in protein synthesis. To determine whether UVA radiation affects PTEN mRNA stability, we treated cells with a DNA transcription suppressor, actinomycin D (Fig. 2C). Little difference was observed in the rate of decrease of PTEN mRNA levels between normal HaCaT cells and ULTH cells at different times post-actinomycin D, suggesting that UVA does not affect PTEN mRNA stability either. In contrast, we found that chronic UVA significantly decreased the transcriptional activity of the PTEN promoter as compared with the sham control (Fig. 2D; P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). These results indicate that PTEN down-regulation by UVA is mediated via suppression of PTEN transcription.

Fig. 2. Chronic UVA radiation down-regulates PTEN transcription but does not affect PTEN protein stability or mRNA stability.

A, immunoblot analysis of PTEN and β-actin in HaCaT and ULTH cells at different times post-CHX (50 μg/ml). B, quantification of PTEN levels in A. C, real-time PCR analysis of PTEN mRNA levels in HaCaT and ULTH cells at different times post-actinomycin D (1 μM). D, reporter assay using PTEN promoter reporter in HaCaT and ULTH cells. *, p < 0.05, significant difference between HaCaT and ULTH cells. E, Immunoblot analysis of PTEN, p-AKT, AKT, p-ERK, ERK, p-EGFR, EGFR and β-actin in HaCaT and ULTH cells after treatment with AC (0, 0.5 and 1 μM) for 6 days. Medium containing vehicle or AC was replaced daily.

Promoter methylation is an important mechanism of silencing gene expression during development and cancer pathogenesis (39). To determine the role of PTEN promoter methylation in UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation, HaCaT and ULTH cells were treated with a potent DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (AC). In HaCaT cells, AC treatment decreased PTEN expression in a dose-dependent manner in parallel with increasing ERK and AKT activation (Fig. 2E). A similar pattern of increased ERK/AKT activation and decreased PTEN expression was observed in ULTH cells in response to AC (Fig. 2E). These data suggest that promoter methylation is not involved in UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation.

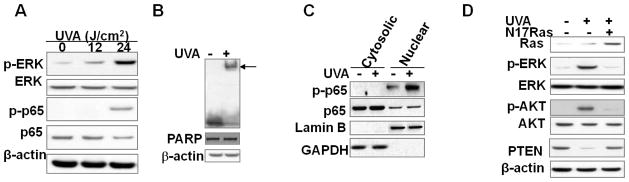

Activation of Ras and its downstream pathways play important roles in PTEN down-regulation induced by acute exposure of UVA irradiation

To determine the molecular pathway that mediates UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation, we analyzed the role of the oncogene Ras as well as the transcription factor NF-κB, both of which have been shown to suppress PTEN expression (40, 41). Our previous studies have demonstrated that UVA induces a delayed and sustained ERK activation through Ras activation (42). ERK was activated following exposure to 12 and 24 J/cm2 UVA in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). The phosphorylation of p65 (NF-κB subunit) was detected following exposure to 24 J/cm2 UVA, but not to 12 J/cm2 UVA (Fig. 3A). NF-κB activation was further confirmed by gel shift analysis in sham- and UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells at 6 h post-UVA (Fig. 3B). Both basal and UVA-induced p65 phosphorylation was exclusively localized in the nucleus (Fig. 3C). To determine the role of Ras in PTEN down-regulation, we inhibited Ras by transfecting HaCaT cells with a construct expressing dominant negative Ras (N17Ras). Expression of N17Ras completely abolished the increase in ERK and AKT activation induced by UVA exposure and prevented UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation (Fig. 3D). These results demonstrate that Ras activation is required for UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation.

Fig. 3. Activation of Ras and its downstream pathways play important roles in PTEN down-regulation induced by acute UVA radiation.

A, immunoblot analysis of p-ERK, ERK, and β-actin in sham- or UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells (12 and 24 J/cm2) at 6 h post-UVA. B, gel shift analysis of NF-κB activation in sham-or UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells at 6 h post-UVA. C, immunoblot analysis of p-p65 and p65 in cytosolic and nuclear fractions from sham- or UVA-irradiated cells collected at 6 h. Lamin B (nuclear) and GAPDH (cytosolic) blots were used as biomarkers for protein fractionation. D, immunoblot analysis of p-ERK, ERK, p-AKT, AKT, and total Ras in vector- or N17Ras-infected HaCaT cells at 6 h post-UVA or -sham irradiation.

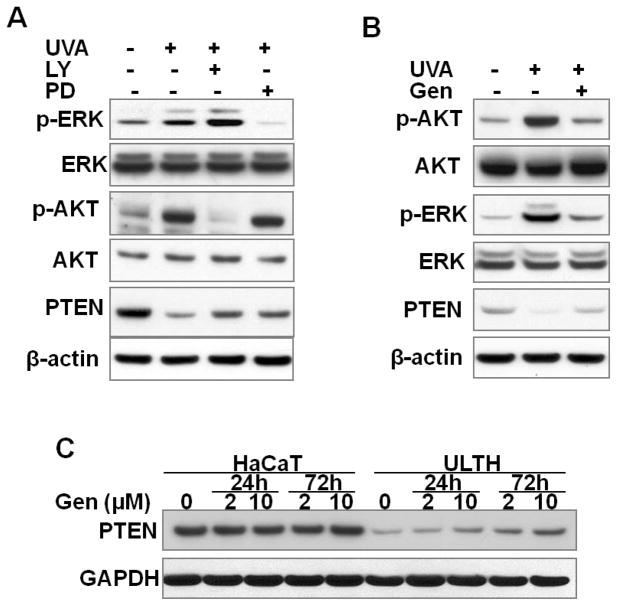

PTEN down-regulation is mediated by activation of ERK and AKT

To determine the role of the ERK and AKT pathways in PTEN suppression by UVA radiation, NHEK cells were irradiated with acute UVA in the presence or absence of the inhibitors LY2940002 (LY) or PD98059 (PD). LY is a specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) that inhibits AKT activation, and PD is a specific inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK) kinase 1 (MEK) that inhibits ERK activation. The presence of LY or PD abolished the AKT or ERK activation, respectively (Fig. 4A). In the meantime, the levels of PTEN protein were increased by treatment with LY or PD. These data indicate that the ERK and AKT pathways are critical for UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation.

Fig. 4. Role of ERK and AKT pathways in PTEN down-regulation.

A, immunoblot analysis of p-ERK, ERK, p-AKT, AKT, PTEN, and β-actin in NHEK cells at 24 h post-final UVA irradiation consisting of four daily UVA treatments (5 J/cm2), in the presence or absence of the PI3K/AKT inhibitor LY294002 (LY, 5 μM) or the MEK1/ERK inhibitor PD98059 (PD, 10 μM). B, immunoblot analysis of p-ERK, ERK, p-AKT, AKT, PTEN, and β-actin in NHEK cells at 24 h post-final UVA irradiation consisting of four daily UVA treatment (5 J/cm2), in the presence or absence of genistein (Gen, 2 μM). C, immunoblot analysis of PTEN and β-actin in HaCaT and ULTH cells treated with vehicle or genistein (2 or 10 μM) for 24 or 72 h.

To further confirm the roles of ERK and AKT activation in PTEN expression, we determined the effect of genistein (Gen), a natural tyrosine kinase inhibitor which has been reported to inhibit the phosphorylation of both ERK and AKT (43–45). Genistein decreased UVA-induced ERK and AKT activation while it partially restored PTEN levels in NHEK cells after UVA radiation (Fig. 4B). Considering the critical role of PTEN as a tumor suppressor in skin homeostasis, induction of PTEN expression may prove beneficial in preventing carcinogenesis. Thus, we further examined the effect of genistein on PTEN expression in ULTH cells compared with HaCaT cells. When ULTH cells were treated with different doses of genistein, the PTEN levels were increased at 24 and 72 h after treatment with 2 or 10 μM genistein (Fig. 4C). The induction of PTEN expression is both time- and dose-dependent. Taken together, these data indicate that ERK and AKT activation negatively regulates the PTEN levels following UVA damage, and that PTEN suppression induced by both chronic and acute UVA radiation can be partially reversed by blocking ERK/AKT pathways.

DISCUSSION

Both UVA and UVB in sunlight and tanning beds are the major environmental risk factors for skin cancer. However, UVA has been considered safe and has been less studied. The tumor suppressor PTEN plays an important role in skin homeostasis, acts as a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT pathway in both humans and mice (31), and prevents UVA-induced skin tumorigenesis (35). In the current studies, we investigated the molecular mechanism by which UVA down-regulates PTEN. Our results clearly indicate that chronic UVA exposure decreases PTEN mRNA and protein levels. Subchronic or acute UVA radiation down-regulates PTEN in human HaCaT and NHEK cells and artificial skin culture as well as in mouse skin. We found that PTEN down-regulation induced by chronic UVA radiation does not involve alterations in the stability of either PTEN protein or mRNA, but occurs at the transcriptional level independent of promoter methylation. At the molecular level, Ras-dependent activation of the AKT and ERK pathways play important roles in UVA-induced PTEN down-regulation.

We found that the transcription factor NF-κB is activated by UVA in HaCaT cells, likely through Ras-dependent ERK/MSK1 activation, as UVA induces p65 phosphorylation at ser276, an MSK1 phosphorylation site (46, 47). It has been reported that NF-κB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) suppresses PTEN transcription, independent of p65DNA binding or transcription function, but involves sequestration of limiting pools of the transcriptional coactivators CBP/p300 byp65 (41). It is possible that nuclear ERK activation (42) induces phosphorylation of nuclear p65 and thereby suppresses PTEN transcription.

It appears that both ERK and AKT activation play important roles in UVA-induced PTEN suppression, as inhibition of the MEK1/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways can rescue PTEN expression following UVA damage. Inhibition of ERK activation, AKT activation, or both only partially recovered down-regulation of the PTEN protein seen in the control, suggesting that additional regulatory mechanisms are involved. Nevertheless, the recovery of PTEN levels was also found in ULTH cells treated with genistein, indicating that PTEN suppression is at least partially reversible. Longer genistein treatment may further increase PTEN expression in ULTH cells. It is also possible that genistein increases PTEN expression through demethylation and acetylation of histone H3 Lysine 9 (48). In addition to NF-κB, other transcription factors may be involved, including AP-1 (40, 49), ΔNp63α (50), and GRHL3 (51). Further investigation is needed to elucidate the role of these pathways in UVA-induced PTEN suppression. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that controlling ERK and/or AKT activation is critical for maintaining PTEN expression.

In summary, our results demonstrate that chronic, subchronic, and acute UVA radiation down-regulates PTEN at the protein and mRNA levels both in vitro and in vivo, which requires the Ras-dependent ERK and AKT pathways. Our studies provide compelling evidence that UVA alone, at environmentally relevant doses from sunlight and particularly tanning beds, has the potential to be a human skin carcinogen by itself or to sensitize the skin to further UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis by down-regulating PTEN. Identifying PTEN as a critical molecular target of UVA may provide us with unique insights for the development of chemopreventive and therapeutic strategies for skin cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant ES016936 (YYH), the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center Pilot program (P30 CA014599), the CTSA (NIH UL1RR024999), and the UC Friends of Dermatology Endowed Fund. We thank Terri Li for the Ki67 immunohistochemistry, Dr. Patrick J. Hayden (MatTek Corporation, MA, USA) for providing EpiDerm culture, Dr. John O’Brian (University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL) for providing the N17Ras construct, Dr. Ian de Belle (Burnham Institute of Medical Research) for providing the PTEN promoter, and Dr. Ann Motten for critical reading of the manuscript. This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Colin F. Chignell.

Abbreviations

- AC

5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine, also called decitabine

- AKT

also called protein kinase B

- CHX

cycloheximide

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- MEK1

an upstream kinase of ERK

- NHEK

normal human epidermal keratinocytes

- skin cancer

non-melanoma skin cancer

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- ULTH

UVA-Long-Term-irradiated HaCaT cells

- UVA

ultraviolet A (315–400 nm)

- UVB

Ultraviolet B (280–315 nm)

- Veh

vehicle

References

- 1.Bowden GT. Prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer by targeting ultraviolet-B-light signalling. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson TM, Dolan OM, Hamilton TA, Lu MC, Swanson NA, Lowe L. Clinical and histologic trends of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:681–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willis I, Menter JM, Whyte HJ. The rapid induction of cancers in the hairless mouse utilizing the principle of photoaugmentation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1981;76:404–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12520945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das M, Bickers DR, Santella RM, Mukhtar H. Altered patterns of cutaneous xenobiotic metabolism in UVB-induced squamous cell carcinoma in SKH-1 hairless mice. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1985;84:532–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12273527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong BK, Kricker A. The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63:8–18. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Gruijl FR, Sterenborg HJ, Forbes PD, et al. Wavelength dependence of skin cancer induction by ultraviolet irradiation of albino hairless mice. Cancer research. 1993;53:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noonan FP, Recio JA, Takayama H, et al. Neonatal sunburn and melanoma in mice. Nature. 2001;413:271–2. doi: 10.1038/35095108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Fabo EC, Noonan FP, Fears T, Merlino G. Ultraviolet B but not ultraviolet A radiation initiates melanoma. Cancer research. 2004;64:6372–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornung RL, Magee KH, Lee WJ, Hansen LA, Hsieh YC. Tanning facility use: are we exceeding Food and Drug Administration limits? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003;49:655–61. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young AR. Tanning devices--fast track to skin cancer? Pigment cell research/sponsored by the European Society for Pigment Cell Research and the International Pigment Cell Society. 2004;17:2–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0749.2003.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Weelden H, van der Putte SC, Toonstra J, van der Leun JC. UVA-induced tumours in pigmented hairless mice and the carcinogenic risks of tanning with UVA. Archives of dermatological research. 1990;282:289–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00375721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Laat A, van der Leun JC, de Gruijl FR. Carcinogenesis induced by UVA (365-nm) radiation: the dose-time dependence of tumor formation in hairless mice. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1013–20. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bech-Thomsen N, Wulf HC. Carcinogenic potential of fluorescent UV tanning sources can be estimated using the CIE erythema action spectrum. International journal of radiation biology. 1993;64:445–50. doi: 10.1080/09553009314551631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bech-Thomsen N, Wulf HC, Poulsen T, Christensen FG, Lundgren K. Photocarcinogenesis in hairless mice induced by ultraviolet A tanning devices with or without subsequent solar-simulated ultraviolet irradiation. Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine. 1991;8:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agar NS, Halliday GM, Barnetson RS, Ananthaswamy HN, Wheeler M, Jones AM. The basal layer in human squamous tumors harbors more UVA than UVB fingerprint mutations: a role for UVA in human skin carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4954–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401141101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasparro FP. Sunscreens, skin photobiology, and skin cancer: the need for UVA protection and evaluation of efficacy. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108 (Suppl 1):71–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterenborg HJ, van der Leun JC. Tumorigenesis by a long wavelength UV-A source. Photochemistry and photobiology. 1990;51:325–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1990.tb01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelfkens G, de Gruijl FR, van der Leun JC. Tumorigenesis by short-wave ultraviolet A: papillomas versus squamous cell carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 1991;12:1377–82. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.8.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Autier P, Dore JF, Negrier S, et al. Sunscreen use and duration of sun exposure: a double-blind, randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1304–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.15.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bissonnette R, Allas S, Moyal D, Provost N. Comparison of UVA protection afforded by high sun protection factor sunscreens. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2000;43:1036–8. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.109299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He YY, Pi J, Huang JL, Diwan BA, Waalkes MP, Chignell CF. Chronic UVA irradiation of human HaCaT keratinocytes induces malignant transformation associated with acquired apoptotic resistance. Oncogene. 2006;25:3680–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wischermann K, Popp S, Moshir S, et al. UVA radiation causes DNA strand breaks, chromosomal aberrations and tumorigenic transformation in HaCaT skin keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2008;27:4269–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Gruijl FR. Photocarcinogenesis: UVA vs UVB. Methods in enzymology. 2000;319:359–66. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)19035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Gruijl FR. Photocarcinogenesis: UVA vs. UVB radiation Skin pharmacology and applied skin physiology. 2002;15:316–20. doi: 10.1159/000064535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Kranen HJ, de Laat A, van de Ven J, et al. Low incidence of p53 mutations in UVA (365-nm)-induced skin tumors in hairless mice. Cancer research. 1997;57:1238–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black HS, deGruijl FR, Forbes PD, et al. Photocarcinogenesis: an overview. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology. 1997;40:29–47. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valencia A, Kochevar IE. Nox1-based NADPH oxidase is the major source of UVA-induced reactive oxygen species in human keratinocytes. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2008;128:214–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waster PK, Ollinger KM. Redox-dependent translocation of p53 to mitochondria or nucleus in human melanocytes after UVA- and UVB-induced apoptosis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2009;129:1769–81. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He YY, Huang JL, Block ML, Hong JS, Chignell CF. Role of phagocyte oxidase in UVA-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in keratinocytes. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2005;125:560–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruls WA, Slaper H, van der Leun JC, Berrens L. Transmission of human epidermis and stratum corneum as a function of thickness in the ultraviolet and visible wavelengths. Photochem Photobiol. 1984;40:485–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1984.tb04622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ming M, He YY. PTEN: new insights into its regulation and function in skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2109–12. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Endersby R, Baker SJ. PTEN signaling in brain: neuropathology and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2008;27:5416–30. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ming M, Shea CR, Feng L, Soltani K, He YY. UVA induces lesions resembling seborrheic keratoses in mice with keratinocyte-specific PTEN downregulation. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1583–6. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He YY, Council SE, Feng L, Chignell CF. UVA-induced cell cycle progression is mediated by a disintegrin and metalloprotease/epidermal growth factor receptor/AKT/Cyclin D1 pathways in keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3752–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ming M, Han W, Maddox J, et al. UVB-induced ERK/AKT-dependent PTEN suppression promotes survival of epidermal keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2010;29:492–502. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ming M, Shea CR, Guo X, et al. Regulation of global genome nucleotide excision repair by SIRT1 through xeroderma pigmentosum C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22623–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010377108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baylin SB. DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2 (Suppl 1):S4–11. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasudevan KM, Burikhanov R, Goswami A, Rangnekar VM. Suppression of PTEN expression is essential for antiapoptosis and cellular transformation by oncogenic Ras. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10343–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vasudevan KM, Gurumurthy S, Rangnekar VM. Suppression of PTEN expression by NF-kappa B prevents apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1007–21. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1007-1021.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He YY, Huang JL, Chignell CF. Delayed and sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in human keratinocytes by UVA: implications in carcinogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53867–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan GR, Xiao CL, He GW, et al. Global phosphoproteomic effects of natural tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein, on signaling pathways. Proteomics. 2010;10:976–86. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee S, Li Y, Wang Z, Sarkar FH. Multi-targeted therapy of cancer by genistein. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:226–42. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akiyama T, Ishida J, Nakagawa S, et al. Genistein, a specific inhibitor of tyrosine-specific protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5592–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, Chariot A. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB and IkappaB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reber L, Vermeulen L, Haegeman G, Frossard N. Ser276 phosphorylation of NF-kB p65 by MSK1 controls SCF expression in inflammation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kikuno N, Shiina H, Urakami S, et al. Genistein mediated histone acetylation and demethylation activates tumor suppressor genes in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:552–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silvers AL, Bowden GT. UVA irradiation-induced activation of activator protein-1 is correlated with induced expression of AP-1 family members in the human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;75:302–10. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)075<0302:uiiaoa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leonard MK, Kommagani R, Payal V, Mayo LD, Shamma HN, Kadakia MP. DeltaNp63alpha regulates keratinocyte proliferation by controlling PTEN expression and localization. Cell Death Differ. 18:1924–33. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darido C, Georgy SR, Wilanowski T, et al. Targeting of the tumor suppressor GRHL3 by a miR-21-dependent proto-oncogenic network results in PTEN loss and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]