Abstract

Inherited vascular malformations are commonly autosomal dominantly inherited with high, but incomplete, penetrance; they often present as multiple lesions. We hypothesized that Knudson’s two-hit model could explain this multifocality and partial penetrance. We performed a systematic analysis of inherited glomuvenous malformations (GVMs) by using multiple approaches, including a sensitive allele-specific pairwise SNP-chip method. Overall, we identified 16 somatic mutations, most of which were not intragenic but were cases of acquired uniparental isodisomy (aUPID) involving chromosome 1p. The breakpoint of each aUPID is located in an A- and T-rich, high-DNA-flexibility region (1p13.1–1p12). This region corresponds to a possible new fragile site. Occurrences of these mutations render the inherited glomulin variant in 1p22.1 homozygous in the affected tissues without loss of genetic material. This finding demonstrates that a double hit is needed to trigger formation of a GVM. It also suggests that somatic UPID, only detectable by sensitive pairwise analysis in heterogeneous tissues, might be a common phenomenon in human cells. Thus, aUPID might play a role in the pathogenesis of various nonmalignant disorders and might explain local impaired function and/or clinical variability. Furthermore, these data suggest that pairwise analysis of blood and tissue, even on heterogeneous tissue, can be used for localizing double-hit mutations in disease-causing genes.

Introduction

Glomuvenous malformations (GVMs [MIM 601749]) are hyperkeratotic bluish-purple cutaneous lesions and often have a cobblestone-like appearance. GVMs account for about 5% of venous anomalies referred to specialized centers.1 On pathologic examination, GVMs are characterized by distended venous channels with flat endothelium surrounded by variable numbers of rounded abnormal mural glomus cells2 (Figure 1). These are abnormally differentiated vascular smooth-muscle cells likely to be at the origin of the lesion.3

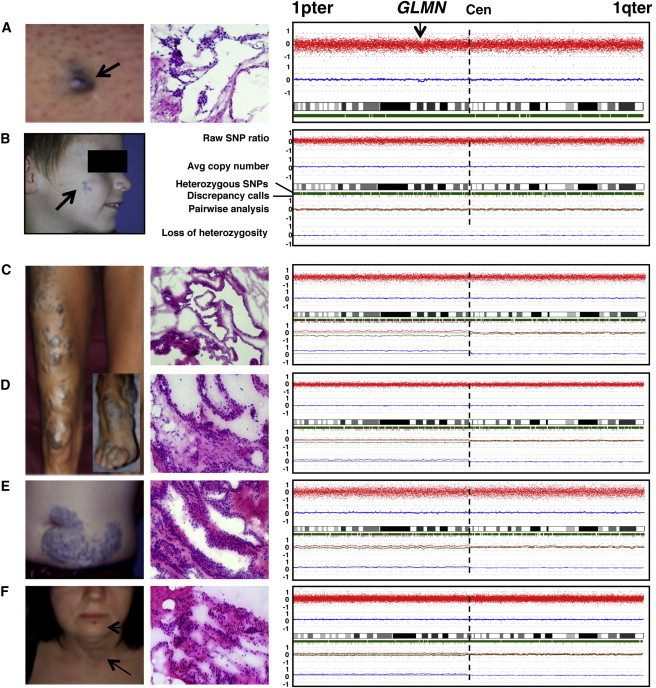

Figure 1.

Second-Hit Mutations in Six GVMs

Clinical photograph (left), hematoxylin and eosin histology (middle), and SNP-chip-based genotype and copy-number estimates for chromosome 1 (right).

(A) GVM on left thigh of GVM71-12 has a partial deletion in 1p22.2–22.1, containing GLMN.

(B) Cheek lesion of GVM36-II-1. This tissue has a partial intragenic deletion (Table 1) yet no alteration in pairwise copy-number analysis.

(C–F) Four representative GVM tissues from three patients with 1p aUPID: (C) right leg, (D) right foot, (E) abdomen, and (F) neck. Five additional GVMs with a similar profile are shown in Figure S1.

GVM is transmitted as an autosomal-dominant trait with variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance, which is 92.7% at 20 years of age.3 Genetic studies have localized the disease-causing mutations in glomulin (GLMN) on the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p22.1).4–6 To date, 40 distinct germline mutations have been identified in 162 families3,7,8 (P.B., L.M.B., M.W., J.B.M., and M.V., unpublished data). Among these, the most frequent mutation (c.157_161del, formerly c.157delAAGAA; Table S1, available online) was found in 72 families, and 86.5% of families have one of 16 shared mutations. All mutations are thought to cause loss of function. The inherited mutations alone are not sufficient to explain the high phenotypic variability (number, size, and location of lesions), reduced penetrance, and development of new small lesions with time. We hypothesized that Knudson’s two-hit model for retinoblastoma (MIM 180200), i.e., the association between an inherited and a somatic mutation, could be the explanation.9 Identifying such changes with the use of lesional DNA for screening for exonic changes has been relatively fruitless; there are only few reports in some inherited vascular anomalies.10–13 To further investigate the two-hit hypothesis, we used laser-capture microdissection (LCM), cDNA analysis, sequencing, and paired allele-specific SNP-chip copy-number analysis of fresh GVM tissue.

Material and Methods

Subject Recruitment

Informed consent was obtained from all the individuals prior to their participation in the study, which was approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty at the Université catholique de Louvain (Brussels, Belgium). Twenty-eight GVM lesions and corresponding blood samples were collected from 26 individuals (Table 1). Additional paired blood and tissue samples were collected from 41 individuals with other vascular anomalies. Thirteen tissue samples of polycystic kidney disease (PKD [MIM 173900 and MIM 613095]) and their respective blood samples were also collected and analyzed, given that somatic second hits have been reported in some, but not all, such lesions. Moreover, uniparental disomy (UPD) has been reported.14,15

Table 1.

The 16 Somatic Second-Hit Mutations identified in 28 GVMs

| Individual and Tissue | Gender | Inherited Mutationa | Tissual RNA | Glomus Cell DNA | Arrays vs. Controls | Pairwise Arrays |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVM43-II-1 | M | c.157_161del | r.1141_1668delins1141–100_1141–48 | c.1141–42C>G | NT | NT |

| GVM107-10 | M | c.395–1G>A | r.714_735del | c.735+1G>A | NT | NT |

| GVM36-II-1 | M | c.395–1G>A | LOH WT allele | LOH WT + SNP i8d | - | - |

| GVM71-12 | F | c.107dup | LOH WT allele | LOH WT allele | del1p22 | NT |

| GVM7-810b | F | c.107dup | LOH WT allele | LOH WT + SNP i8d | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM22-100-legb | F | c.157_161del | LOH WT allele | LOH WT allele | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM22-100-footb | F | c.157_161del | LOH WT allele | LOH WT allele | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM67-11 | M | c.395–1G>C | LOH WT allele | NT | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM16-IV-1c | F | c.743dup | - | LOH SNP i8d | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM4-10b | M | c.554_558delinsG | - | NT | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM24-10b | F | c.1711_1712del | - | - | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM98-10 | F | c.157_161del | NT | NT | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM150-10 | F | c.157_161del | NT | NT | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM16-IV-2c | F | c.743dup | NT | - | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM80-10 | M | c.422dup | - | - | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM185 | M | c.422dup | - | - | - | 1p aUPID |

| GVM14-241b | F | c.1547C>G | - | - | - | - |

| GVM16-IV-2c | F | c.743dup | NT | - | - | - |

| GMV33-10b | M | c.108C>A | NT | NT | - | - |

| GVM67-1 | M | c.395–1G>C | NT | NT | - | - |

| GVM71-100 | M | c.107dup | - | NT | - | - |

| GVM90-101 | M | c.157_161del | NT | NT | - | - |

| GVM94-10-scre | M | c.422dup | - | - | - | - |

| GVM94-10-foot | M | c.422dup | NT | NT | - | - |

| GVM99-10 | M | c.157_161del | NT | NT | - | - |

| GVM100-10 | F | c.1179_1181del | NT | NT | - | - |

| GVM111-100 | M | c.36_37del | NT | NT | - | - |

| GVM127-11 | F | c.743dup | NT | NT | - | - |

The following abbreviations are used: M, male; F, female; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; -, no alteration; NT, not tested; and aUPID, acquired uniparental isodisomy.

Mutations in GLMN (RefSeq NM_053274.2) were (re)named according to HGVS guidelines. RefSeq NG_009796 was used for the two mutations observed in tissual RNA (GVM43-II-1 and GVM107-10).

Pedigree in Brouillard et al.3

Pedigree in Brouillard et al.6

rs1487540.

From the scrotum.

DNA and mRNA Samples

Vascular tissues were collected in liquid nitrogen immediately after resection and were stored at −80°C directly or after optimal-cutting-temperature (OCT) embedding. We used the Puregene DNA extraction kit (Gentra) for extraction of blood or tissual DNA (five sections of 30 μm each) and Tripure (Roche) for purification of total RNA.

mRNA-Based Screening

The SuperScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) was used for RT-PCR. The GLMN full-length transcript was amplified and used as a template for 12 overlapping fragments (0.4–1.0 kb). The amplicons were resolved on agarose gel for the detection of abnormal bands. The entire mRNA was sequenced for the samples screened (Table 1). In the case of double sequence, amplicons were cloned into pCR2.1 (TOPO TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen, Life Technologies), and several clones were sequenced.

LCM

LCM was performed on a PALM Microlaser with the use of 5 μm cryosections stained with hematoxylin III (Gill) for the identification of nuclei. Several groups of glomus cells or dermal cells were microdissected, 10–20 μl of DNA extraction buffer (0.5 M EDTA pH 8, 1 M Tris pH 8, Tween 20, and 20 mg/ml proteinase K) was added, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 55°C. Proteinase K was heat inactivated, and 2–3 μl was used in 50 μl PCR for 40 cycles. Amplicons were analyzed either by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) on a WAVE 3500 HS system (Transgenomic) or by sequencing on a CEQ2000 fluorescent capillary sequencer (Beckman Coulter) or an ABI 3130xl (Life Technologies).

Analysis of Mutations

To predict the effects of intragenic mutations on splicing, we used Human Splicing Finder software and MaxEntScan software for short sequence motifs.

Microarray Analyses

Molecular karyotyping was performed in all samples with Affymetrix Human Mapping 250K NspI or SNP6.0 SNP chips according to the manufacturer’s (Affymetrix) instructions. In brief, total genomic DNA was digested, and fragments were ligated to adaptors and amplified with a single primer. After purification of the PCR products, amplicons were quantified, fragmented, labeled, and hybridized on the array. Signal intensities were measured with Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G.

Bioinformatic Analyses

Results were analyzed with Affymetrix Genotyping Console 4 and with the Copy Number Analyzer for GeneChip (CNAG) 3.3.0.1 for copy-number changes. Genotype-calling algorithms using the Bayesian Robust Linear Model with Mahalanobis or the customized Expectation Maximization algorithm (Birdseed v.2) were used for generating the genotypes for 250K or SNP6.0 chips, respectively. In non-self-reference analysis, a hidden Markov model (HMM) was used for identifying statistically significant deviations in logarithmic ratios of signal intensities between SNPs on the array. The reference data were drawn from a pool of 182 (250K array) or 69 (SNP6.0 array) arrays. Within this pool of reference arrays, the signal-intensity SD values were ranked, and the arrays with the smallest SD were used. Each array was referenced to at least six other arrays of unrelated individuals. In pairwise analysis (comparing tissue- and blood-derived DNA), copy-number variations in the two alleles were separately analyzed on the basis of the genotyping information. Signal ratios were plotted without the use of a logarithm. Copy-number status was derived via algorithms based on the HMM.16,17

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed as previously described.18 OCT-embedded frozen sections (5 μm) were hybridized overnight with bacterial-artificial-chromosome probes RP11-163M2 (1p22.1, covering the GLMN locus) and RP11-181G2 (control probe on 1p36.33). Control hybridizations were performed with commercial probes Telomere 1q Spectrum Orange and Telomere 7p Spectrum Green (Abbott Molecular).

Results

No GLMN Second Hit Detected in DNA from GVMs

To identify somatic mutations in GLMN (RefSeq accession number NM_053274.2), we isolated genomic DNA from 28 resected GVM specimens (26 individuals, Table 1). The inherited mutations were already known for most of the individuals3,7,19 (P.B., L.M.B., M.W., J.B.M., and M.V., unpublished data). We screened the 19 exons and their splice sites of GLMN. This whole-tissue approach did not reveal any somatic changes in GLMN but uncovered the heterozygous inherited mutations that were also present in blood-derived DNA (Table 1).

Intragenic GLMN Second Hits Detected in mRNA from GVMs

To increase sensitivity of our screens, we extracted total RNA from a set of 14 frozen GVMs (Table 1). The GLMN transcripts were screened in 12 overlapping fragments. Besides the allele that carried the known inherited mutation of family GVM43-II-1, the amplicon covering the full-length cDNA had a shorter product. This allele was wild-type with regard to the germline mutation but had a deletion of exons 13–18 and an insertion of 54 bp from intron 12 (r.1141_1668delins1141–100_1141–48). Using LCM tissue, we discovered in the middle of intron 12 a substitution (c.1141–42C>G) causing a new strong splice site leading to the deletion (Table 1).

For GVM107-10, we found an allele with a deletion of the first eight nucleotides of exon 6 (c.395_402del). This most likely resulted from the inherited splice-site mutation in the last nucleotide of intron 5 (Table 1). The second allele had a deletion of the last 22 nucleotides of exon 7 (r.714_735del). In microdissected tissue, we detected a substitution of the first nucleotide of intron 7 (c.735+1G>A). This destroyed the canonical splice site. An alternative consensus site lay 22 nucleotides upstream (Table 1), corresponding to the deletion observed in mRNA.

For six other tissues, we detected a loss or a significant decrease in expression of the allele that did not carry the inherited mutation (Table 1), suggesting a somatic mutation in regulatory elements, epigenetic modification, and/ or loss of heterozygosity (LOH). No genetic mutation was found in the six other lesions.

LOH Detected in DNA from Microdissected Tissues

To study LOH in GVMs, we extracted genomic DNA from microdissected tissues of ten lesions (Table 1). Six samples demonstrated LOH: GVM7-810, GVM22-100-leg, GVM22-100-foot, GVM36-II-1, and GVM71-12 were homozygous for the respective inherited mutation, and GVM7-810, GVM16-IV-1, and GVM36-II-1 lost heterozygosity such that they were missing one allele for a SNP (rs1487540) in intron 8 of GLMN. No mutation was detected in the other four samples tested. These results suggest the presence of larger genomic alterations encompassing, at least partially, the GLMN locus.

aUPID Detected in GVMs by Pairwise Copy-Number Analysis

We used Affymetrix SNP-chip arrays on DNAs extracted from a series of 26 GVMs to define the extent of the LOH detected in microdissected glomus cells and to detect additional tissues with LOH. The hybridization signals were first compared to those of a large reference set of 260 unaffected and unrelated blood samples. In GVM71-12, we detected an interstitial deletion in 1p22.2–22.1 (the region containing GLMN) and no other chromosomal abnormality (Figure 1A and Table 1). Within the deleted region, we identified a large number of heterozygous SNPs with an average copy-number estimate of 1.7, which indicates tissue heterogeneity (Figure 1A). In all other GVMs, the overall copy number was equal to 2, and there was no LOH or other variation (data not shown).

Next, we compared each GVM to its respective blood-derived DNA in a pairwise manner. In GVM36-II-1, in which microdissected tissue was homozygous for the inherited GLMN mutation and the intronic SNP rs1487540, no chromosomal aberration was found (Figure 1B and Table 1). This indicates that the size of the LOH was below 25 kb, the resolution of the 250K chip array used. All other samples also showed two copies of each chromosome (Figures 1C–1F and Figures S1A–S1E). In 12 GVMs, the short arm of chromosome 1 had significantly increased genotypic discordance between lesional DNA and the corresponding lymphocytic DNA (Figures 1C–1F and Figures S1A–S1E). Moreover, when we compared the copy-number status of each allele separately by pairwise analysis of blood and tissue, we observed a statistically significant divergence. This was accompanied by increased LOH on 1p. This copy-neutral LOH suggests that the loss of one allele is compensated by the gain of the other allele—evidence of acquired uniparental isodisomy (aUPID)20,21 (Figures 1C–1F, Figures S1A–S1E, and Table 1). The fact that 1p remained heterozygous in all tissues indicates that aUPID is present only in a subpopulation of cells. Tissual heterogeneity increases the difficulty in detecting aUPID (Figures 1C–1F and Figures S1A–S1E).

No Aneuploidy Detected in GVMs

To confirm the presence of two copies of the short arm of chromosome 1 in GVMs, we analyzed three different lesions by FISH (Table 2 and Figure S2). In all three lesions, the number of cells showing two hybridization signals for the two probes in 1p was identical to that of the two control probes on 1q and 7p, i.e., 93–95 out of 100 nuclei counted in resected glomus cells.

Table 2.

Diploid Glomus Cells in Three GVM Lesions out of 100 Nuclei Analyzed by FISH Locus-Specific Probe

| Individual and Tissue |

Percentage of Diploid Glomus Cells |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p22.1a | 1p36.33b | 1qterc | 7pterd | |

| GVM22-100-leg | 93% | 93% | 94% | 94% |

| GVM22-100-foot | 93% | 95% | 94% | 94% |

| GVM98-10 | 96% | 96% | 92% | 92% |

| Average | 94% | 95% | 93% | 93% |

RP11-163M2.

RP11-181G12.

Telomere 1q Spectrum Orange.

Telomere 7p Spectrum Green.

Break Points of Identified aUPID Localized to 1p13.1–1p12

To map the breakpoints of each case of aUPID, we combined the LOH and pairwise copy-number data. Using a gliding window set to ten SNPs, we scanned the chromosome 1p pericentromeric area from centromere to telomere, and we considered as the breakpoint the region in which we started to detect a deviation between the estimated copy number of an allele in tissue-blood pairs. This corresponded to the starting-point LOH. We found that all identified breakpoints were located in a ∼2.94 Mb region containing ∼60% A and T at 1p13.1–1p12 (Table 3). This region contained multiple tandem repeats of A and T, illustrated by the identification of tandemly repeated structures in DNA sequences (mreps software; Table S1). With the resolution of the technique used, it is impossible to state how many independent sequences and/or sites were involved.

Table 3.

aUPID Breakpoint Boundaries Identified on 1p in 12 GVMs

| Individual and Tissue | Telomeric SNP ID | Centromeric SNP ID | Breakpoint Region Limit (bp) | Size (kb) | Location | Affymetrix Array Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVM80-10 | rs6428670 | rs10494190 | 117,168,713–117,194,463 | 25.8 | 1p13.1 | SNP6.0 |

| GVM98-10 | rs12087175 | rs12410934 | 117,636,914–117,656,082 | 19.2 | 1p13.1 | SNP6.0 |

| GVM150-10 | rs167662 | rs1975283 | 117,929,096–117,944,081 | 15.0 | 1p12 | SNP6.0 |

| GVM7-810a | rs12404666 | rs1146342 | 118,733,848–118,784,700 | 50.9 | 1p12 | SNP6.0 |

| GVM16-IV-2b | rs1779430 | rs12027986 | 119,262,320–119,372,788 | 110.5 | 1p12 | 250K |

| GVM185 | rs17023224 | rs6676180 | 119,434,378–119,584,746 | 150.4 | 1p12 | 250K |

| GVM16-IV-1b | rs17186115 | rs3753263 | 119,631,749–119,711,372 | 79.6 | 1p12 | 250K |

| GVM24-10a | rs860792 | rs1819698 | 119,693,142–119,767,042 | 73.9 | 1p12 | 250K |

| GVM67-11 | rs3753263 | rs1417608 | 119,711,372–119,779,356 | 68.0 | 1p12 | 250K |

| GVM4-10a | rs10489811 | rs3949342 | 119,784,626–119,816,321 | 31.7 | 1p12 | 250K |

| GVM22-100-lega | rs17023814 | rs539799 | 119,897,445–120,009,995 | 112.6 | 1p12 | 250K |

| GVM22-100-foota | rs920513 | rs2289459 | 120,074,129–120,113,001 | 38.9 | 1p12 | 250K |

1p aUPID Not Found in a Series of Other Tissues

To determine whether somatic 1p aUPID is specific to GVMs or is a common somatic event, we analyzed 54 other blood-tissue pairs. These included 41 vascular anomalies, including infantile hemangiomas (MIM 602089) (n = 20), cutaneomucosal-venous malformations (MIM 600195) (n = 4), capillary malformations (CMAVMs [MIM 608354]) (n = 3), and lymphatic malformations (n = 14), as well as tissues from polycystic kidneys (n = 13). None of the 54 samples showed evidence of somatic 1p aUPID (data not shown).

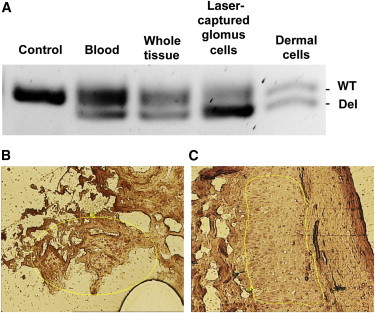

Second Hits Enriched in Glomus Cells

Our difficulty in detecting second hits in GVMs suggested cellular heterogeneity in the resected lesions (illustrated in Figure S3). Because the resected tissue GVM22-100-leg contained overlying skin, we laser captured dermal cells (Figure 2A) and abnormal cells (Figure 2B) for separate DNA analyses. Amplification of a fragment overlapping the inherited mutation (c.157_161del) confirmed that the abnormal cells demonstrated LOH, given that they predominantly contained the allele harboring the germline mutation, whereas dermal cells, whole tissue, and blood were all heterozygous (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Lack of GLMN Is Restricted to the Lesion

(A–C) Amplification of a 95 bp fragment overlapping the inherited mutation (c.157_161del) of GVM22-100 (A) shows enrichment of the mutant allele in microdissected glomus cells (B) compared to overlying dermal cells (C), whole GVM, and blood. The lack of GLMN is restricted to glomus cells.

Discussion

Phenotypic variability in individuals with GVMs, even in those who have the same inherited mutation, suggests that an additional genetic event might trigger the formation of a lesion. Previously, we proposed that this event might be a somatic second hit and identified one such mutation in one GVM specimen. Herein, we screened 28 additional GVMs and identified a second hit in 16 lesions (Table 1); these included two (11.75%) intragenic point mutations, two (11.75%) intragenic deletions, and one (5.9%) interstitial 1p22.2–22.1 deletion containing GLMN. Unexpectedly, the majority of the mutations we identified (12 mutations; 70.6%) were cases of 1p aUPID. These data suggest that somatic second hits are necessary for the formation of GVMs and explain the variable phenotype and incomplete penetrance observed. Moreover, heterozygous glomulin knockout mice are phenotypically normal, but homozygous glomulin knockout mice die in utero (unpublished data). Taken together, these data support the somatic second-hit model for GVM formation.

aUPID discovered in GVMs results in duplication of the mutant allele and loss of the wild-type without causing quantitative loss of other genes. Such a mechanism has been described in cancerous tissues, but not in noncancerous Mendelian disorders. Indeed, if LOH were caused by the deletion of 1p, the result would most likely be progression to malignancy because of the loss of several tumor-suppressor genes that reside in 1p. This finding suggests that aUPID might be involved in various other disorders in which lesions are localized, for example, vascular disorders such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT [MIM 187300]), cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs [MIM 116860]), and CMAVMs, as well as other disorders, such as PKD. It might also explain why second-hit screens (focusing on intragenic mutations) have often been unrewarding. We reported one intragenic somatic second hit in a mucocutaneous-venous malformation10 and one in a GVM,3 and others have found five somatic second hits in CCMs.11–13,22 Screens in HHT have been fruitless, leading to a strong debate regarding the second-hit mechanism as being the explanation for the localized vascular lesions in HHT. Nevertheless, murine studies support the two-hit mechanism in HHT and CCMs.23–25

Mitotic recombination occurs at a higher frequency in centromeres and telomeres than in the rest of the chromosomes.26 Aneuploidy is a direct consequence of chromosomal-segregation errors in mitosis.27 In the 12 GVMs with aUPID, the breakpoints reside close to each other (according to the resolution of the SNP chips) near the centromere at 1p13.1–1p12. This region is rich in A and T sequences. (Table S2). Such A- and T-rich regions have been suggested to be associated with common aphidicolin fragile sites.28 The 1p13.1–1p12 region does not contain a known fragile site. Another possibility is break-induced recombination. The underlying haploinsufficiency in glomulin might play a role in these mechanisms.

A number of studies have recorded an accumulation of somatic mutations in human tissues and support the idea that the mutation rate per cell division is much greater in somatic cells than in germline cells.29 The human somatic mutational rate has been estimated to be less than one mutation per megabase per generation30,31 but as high as 17.7 mutations per megabase throughout the genome of a pulmonary tumor.32 Single-nucleotide substitutions are ∼25 times more common than all other mutations, and deletions are approximately three times more common than insertions, whereas complex mutations are very rare.30 In light of these data, we expected to detect single-nucleotide substitutions. There are no accurate estimates of the frequency of mitotic aUPID— the most common somatic mutation detected in our study—in human cells.

The frequency of germline UPD as the result of impaired meiotic allelic disjunction is estimated at less than 2% in the human genome.33 Therefore, for any chromosome, UPD is expected in only 1/3,500 births.34 aUPID occurs as a postfertilization mitotic recombination event. It has been described in cancers.35 Therefore, aUPID is an attractive model to explain localized dysfunction in various diseases. In the 13 PKD tissues analyzed, no aUPID of 1p or the chromosomes containing the genes associated with PKD types 1 an 2 was identified. However, an individual with neonatal renal cystic disease was reported to be homozygous for a missense mutation due to UPD in PKD type 2.15,36–38

The rate of meiotic, as well as mitotic, recombination has been calculated to be twice as high in females as in males.39 Accordingly, in a series of 12 cases of aUPID, one would expect to see eight to nine in females and three to four in males. In our series, 7 of the 12 GVMs with 1p aUPID occurred in females. There was no difference in transmission of the inherited mutation between paternal and maternal alleles in individuals with lesions with aUPID.

Cellular heterogeneity makes it difficult to determine somatic changes in GVMs, as well as most other disorders. Resected GVMs are composed of endothelial cells, vascular smooth-muscle cells, glomus cells, fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and blood cells (Figure 2 and Figure S3). This diversity complicates detection of somatic mutations in whole tissues, especially at the genomic DNA level, because normal cells can mask low-number mutant cells. To bypass this obstacle, we used both cDNA analysis (to screen GLMN exons only in cells expressing it) and DNA analysis on microdissected lesions. In addition, allele-specific pairwise analyses with SNP chips allowed detection of aUPID even in heterogeneous whole tissue. Our findings underscore the presence of a second-hit mutation that is located in a GVM and that renders it devoid of glomulin. Thus, in a particular individual, the timing of the second hit’s occurrence most likely influences the number of affected cells in the lesion and thus the size of the lesion. This proposal is supported by the fact that the two distant resections of the same lesion of GVM22 (that of the right leg and that of the right foot; Figures 1C and 1D) showed the same somatic mutation (i.e., 1p aUPID).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that somatic second hits explain the wide phenotypic variability of GVMs with regard to size, number, and localization of lesions. These somatic mutations eliminate GLMN locally, most commonly via homozygosity for the inherited loss-of-function mutation due to aUPID. GVMs exemplify aUPID in a noncancerous disorder and suggest a wider implication for aUPID in human disease.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the individuals for their invaluable contributions. These studies were supported by the Belgian Federal Science Policy, Concerted Research Actions (07/12-005) of the French Community of Belgium, the National Institutes of Health (program project P01 AR048564), the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (all to M.V.), and la Lotterie Nationale, Belgium. M.A. is a Scientific Logistics Manager of the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS). V.A. was supported by a fellowship from the Fonds pour la Formation à la Recherche dans l’Industrie et dans l’Agriculture and from the Patrimoine de la Faculté de Médicine of the Université catholique de Louvain. B.A.S.M. was supported by a Patrimoine de la Faculté de Médecine fellowship from the Université catholique de Louvain. He also received a doctoral research grant from the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada. F.P.D. is supported by fellowship from the FRS-FNRS. We thank Ms. Dominique Cottem and Ms. Anne Van Egeren for technical support and Ms. Liliana Niculescu for her secretarial and administrative contributions.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Copy number analyzer for GeneChip (CNAG 3.3.0.1), http://www.genome.umin.jp/

Human Splicing Finder, http://www.umd.be/HSF/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

References

- 1.Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Enjolras O., Vikkula M. Glomuvenous malformation (glomangioma) and venous malformation: Distinct clinicopathologic and genetic entities. Arch. Dermatol. 2004;140:971–976. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.8.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman T.F., Abele D.C. Multiple glomus tumors. A clinical and electron microscopic study. Arch. Dermatol. 1971;103:11–23. doi: 10.1001/archderm.103.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouillard P., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Enjolras O., Ghassibé M., Warman M.L., Tan O.T., Olsen B.R., Vikkula M. Mutations in a novel factor, glomulin, are responsible for glomuvenous malformations (“glomangiomas”) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:866–874. doi: 10.1086/339492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irrthum A., Brouillard P., Enjolras O., Gibbs N.F., Eichenfield L.F., Olsen B.R., Mulliken J.B., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. Linkage disequilibrium narrows locus for venous malformation with glomus cells (VMGLOM) to a single 1.48 Mbp YAC. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;9:34–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boon L.M., Brouillard P., Irrthum A., Karttunen L., Warman M.L., Rudolph R., Mulliken J.B., Olsen B.R., Vikkula M. A gene for inherited cutaneous venous anomalies (“glomangiomas”) localizes to chromosome 1p21-22. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:125–133. doi: 10.1086/302450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouillard P., Olsen B.R., Vikkula M. High-resolution physical and transcript map of the locus for venous malformations with glomus cells (VMGLOM) on chromosome 1p21-p22. Genomics. 2000;67:96–101. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouillard P., Ghassibé M., Penington A., Boon L.M., Dompmartin A., Temple I.K., Cordisco M., Adams D., Piette F., Harper J.I. Four common glomulin mutations cause two thirds of glomuvenous malformations (“familial glomangiomas”): evidence for a founder effect. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:e13. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouillard P., Vikkula M. Genetic causes of vascular malformations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16(Spec No. 2):R140–R149. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Vikkula M., Watkins H., Seidman J., Olsen B.R., Warman M.L. Assignment of a locus for dominantly inherited venous malformations to chromosome 9p. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:1583–1587. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.9.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limaye N., Wouters V., Uebelhoer M., Tuominen M., Wirkkala R., Mulliken J.B., Eklund L., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. Somatic mutations in angiopoietin receptor gene TEK cause solitary and multiple sporadic venous malformations. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:118–124. doi: 10.1038/ng.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akers A.L., Johnson E., Steinberg G.K., Zabramski J.M., Marchuk D.A. Biallelic somatic and germline mutations in cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs): Evidence for a two-hit mechanism of CCM pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:919–930. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gault J., Awad I.A., Recksiek P., Shenkar R., Breeze R., Handler M., Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B.K. Cerebral cavernous malformations: Somatic mutations in vascular endothelial cells. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:138–144. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000348049.81121.C1. discussion 144–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagenstecher A., Stahl S., Sure U., Felbor U. A two-hit mechanism causes cerebral cavernous malformations: Complete inactivation of CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 in affected endothelial cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:911–918. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pei Y., Watnick T., He N., Wang K., Liang Y., Parfrey P., Germino G., St George-Hyslop P. Somatic PKD2 mutations in individual kidney and liver cysts support a “two-hit” model of cystogenesis in type 2 autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1999;10:1524–1529. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1071524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Losekoot M., Ruivenkamp C.A., Tholens A.P., Grimbergen J.E., Vijfhuizen L., Vermeer S., Dijkman H.B., Cornelissen E.A., Bongers E.M., Peters D.J. Neonatal onset autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) in a patient homozygous for a PKD2 missense mutation due to uniparental disomy. J. Med. Genet. 2012;49:37–40. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nannya Y., Sanada M., Nakazaki K., Hosoya N., Wang L., Hangaishi A., Kurokawa M., Chiba S., Bailey D.K., Kennedy G.C., Ogawa S. A robust algorithm for copy number detection using high-density oligonucleotide single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping arrays. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6071–6079. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto G., Nannya Y., Kato M., Sanada M., Levine R.L., Kawamata N., Hangaishi A., Kurokawa M., Chiba S., Gilliland D.G. Highly sensitive method for genomewide detection of allelic composition in nonpaired, primary tumor specimens by use of affymetrix single-nucleotide-polymorphism genotyping microarrays. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:114–126. doi: 10.1086/518809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medves S., Duhoux F.P., Ferrant A., Toffalini F., Ameye G., Libouton J.M., Poirel H.A., Demoulin J.B. KANK1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene, is fused to PDGFRB in an imatinib-responsive myeloid neoplasm with severe thrombocythemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1052–1055. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brouillard P., Enjolras O., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. Glomulin and glomuvenous malformation. In: Epstein C.J., Erickson R.P., Wynshaw-Boris A., editors. Inborn Errors of Development. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. pp. 1561–1565. [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaFramboise T. Single nucleotide polymorphism arrays: A decade of biological, computational and technological advances. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4181–4193. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purdie K.J., Lambert S.R., Teh M.T., Chaplin T., Molloy G., Raghavan M., Kelsell D.P., Leigh I.M., Harwood C.A., Proby C.M., Young B.D. Allelic imbalances and microdeletions affecting the PTPRD gene in cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas detected using single nucleotide polymorphism microarray analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:661–669. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallory S.B., Enjolras O., Boon L.M., Rogers E., Berk D.R., Blei F., Baselga E., Ros A.M., Vikkula M. Congenital plaque-type glomuvenous malformations presenting in childhood. Arch. Dermatol. 2006;142:892–896. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.7.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gault J., Shenkar R., Recksiek P., Awad I.A. Biallelic somatic and germ line CCM1 truncating mutations in a cerebral cavernous malformation lesion. Stroke. 2005;36:872–874. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157586.20479.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park S.O., Wankhede M., Lee Y.J., Choi E.J., Fliess N., Choe S.W., Oh S.H., Walter G., Raizada M.K., Sorg B.S., Oh S.P. Real-time imaging of de novo arteriovenous malformation in a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:3487–3496. doi: 10.1172/JCI39482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald D.A., Shenkar R., Shi C., Stockton R.A., Akers A.L., Kucherlapati M.H., Kucherlapati R., Brainer J., Ginsberg M.H., Awad I.A., Marchuk D.A. A novel mouse model of cerebral cavernous malformations based on the two-hit mutation hypothesis recapitulates the human disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:211–222. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Limaye N., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. From germline towards somatic mutations in the pathophysiology of vascular anomalies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18(R1):R65–R74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaco I., Canela A., Vera E., Blasco M.A. Centromere mitotic recombination in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181:885–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janssen A., van der Burg M., Szuhai K., Kops G.J., Medema R.H. Chromosome segregation errors as a cause of DNA damage and structural chromosome aberrations. Science. 2011;333:1895–1898. doi: 10.1126/science.1210214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dillon L.W., Burrow A.A., Wang Y.H. DNA instability at chromosomal fragile sites in cancer. Curr. Genomics. 2010;11:326–337. doi: 10.2174/138920210791616699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch M. Rate, molecular spectrum, and consequences of human mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:961–968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912629107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondrashov A.S. Direct estimates of human per nucleotide mutation rates at 20 loci causing Mendelian diseases. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:12–27. doi: 10.1002/humu.10147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenman C., Stephens P., Smith R., Dalgliesh G.L., Hunter C., Bignell G., Davies H., Teague J., Butler A., Stevens C. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee W., Jiang Z., Liu J., Haverty P.M., Guan Y., Stinson J., Yue P., Zhang Y., Pant K.P., Bhatt D. The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient. Nature. 2010;465:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature09004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-Santiago B., Malats N., Rothman N., Armengol L., Garcia-Closas M., Kogevinas M., Villa O., Hutchinson A., Earl J., Marenne G. Mosaic uniparental disomies and aneuploidies as large structural variants of the human genome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lalande M. Parental imprinting and human disease. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1996;30:173–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teh M.T., Blaydon D., Chaplin T., Foot N.J., Skoulakis S., Raghavan M., Harwood C.A., Proby C.M., Philpott M.P., Young B.D., Kelsell D.P. Genomewide single nucleotide polymorphism microarray mapping in basal cell carcinomas unveils uniparental disomy as a key somatic event. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8597–8603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pei Y. A “two-hit” model of cystogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? Trends Mol. Med. 2001;7:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)01953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Badenas C., Torra R., Pérez-Oller L., Mallolas J., Talbot-Wright R., Torregrosa V., Darnell A. Loss of heterozygosity in renal and hepatic epithelial cystic cells from ADPKD1 patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;8:487–492. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holt D., Dreimanis M., Pfeiffer M., Firgaira F., Morley A., Turner D. Interindividual variation in mitotic recombination. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:1423–1427. doi: 10.1086/302614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.