Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma are characterized by hyperreactive airway responses that predispose patients to episodes of acute airway constriction. Recent studies suggest a complex paradigm of GABAergic signaling in airways that involves GABA-mediated relaxation of airway smooth muscle. However, the cellular source of airway GABA and mechanisms regulating its release remain unknown. We questioned whether epithelium is a major source of GABA in the airway and whether the absence of epithelium-derived GABA contributes to greater airway smooth muscle force. Messenger RNA encoding glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) 65/67 was quantitatively measured in human airway epithelium and smooth muscle. HPLC quantified GABA levels in guinea pig tracheal ring segments under basal or stimulated conditions with or without epithelium. The role of endogenous GABA in the maintenance of an acetylcholine contraction in human airway and guinea pig airway smooth muscle was assessed in organ baths. A 37.5-fold greater amount of mRNA encoding GAD 67 was detected in human epithelium vs. airway smooth muscle cells. HPLC confirmed that guinea pig airways with intact epithelium have a higher constitutive elution of GABA under basal or KCl-depolarized conditions compared with epithelium-denuded airway rings. Inhibition of GABA transporters significantly suppressed KCl-mediated release of GABA from epithelium-intact airways, but tetrodotoxin was without effect. The presence of intact epithelium had a significant GABAergic-mediated prorelaxant effect on the maintenance of contractile tone. Airway epithelium is a predominant cellular source of endogenous GABA in the airway and contributes significant prorelaxant GABA effects on airway smooth muscle force.

Keywords: airway, epithelial, GABA, tone

the airway epithelium and smooth muscle are anatomically positioned to signal via paracrine and autocrine pathways. Well-established examples of paracrine signaling from airway epithelium to airway smooth muscle include the release of epithelial prostaglandins (10) and nitric oxide (19). Epithelial dysfunction has been linked to disease states including asthma, which result in hypercontractility of the smooth muscle, owing in part to aberrant epithelium signaling and impaired barrier function, increased inflammation, and long-term airway remodeling (8). A burgeoning number of recent studies suggest that many paracrine signaling pathways involving growth factors and cytokines released by the epithelium-mesenchyme unit are important in airway smooth muscle reactivity and remodeling (9, 11, 12). Although the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) has classically been perceived as limited to neuronal signaling, recent evidence suggests GABA also plays a novel role as a paracrine signaling molecule in airways. For example, GABAA chloride ion channels, Gi-coupled GABAB metabotropic receptors, GABA transporters, and the enzymes that synthesize GABA (glutamic acid decarboxylase) have all been recently identified on both airway epithelium and airway smooth muscle (3, 15, 16, 22–24).

GABA is synthesized from glutamate by two isoforms of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD; GAD65 and/or GAD67) that have been most extensively characterized in the central nervous system (13). Although prejunctional inhibitory GABAB receptors have been functionally demonstrated in peripheral lung cholinergic nerves (2), GAD expression has yet to be identified in peripheral nerves of the lung. However, GAD protein expression has been identified in both native and cultured airway epithelium (14, 23) although the antibodies employed in these studies did not distinguish between the isoforms. Moreover, the cellular source of endogenous GABA in the airway is unknown.

In the present study we hypothesized that epithelium is an important cellular source of GABA in the airway and that the GAD67 isoform is the primary isoform responsible for GABA synthesis. Furthermore, we hypothesized that endogenous levels of GABA originating from the epithelium have a paracrine effect on GABAA channels expressed on airway smooth muscle, contributing a tonic prorelaxant effect during the maintenance of airway smooth muscle tone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Indomethacin, N-vanillynonanamide (capsaicin analog), pyrilamine, and acetylcholine were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). GABA transporter (GAT) inhibitors were obtained from Tocris (Bristol, UK). Tetrodotoxin was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Human airway tissues.

In accordance with Columbia University's Institutional Review Board, discarded regions of healthy human donor lungs originally harvested for lung transplantation were employed in our studies (deemed not human subjects research under 45 CFR 46). Upon availability, excess tissue was placed in cold M199 media (4°C) and transported to the laboratory, where the epithelial layer was dissected from the underlying muscle layer with the aid of a dissecting microscope and immediately processed for RNA isolation or used in organ bath studies. In functional organ bath studies, intact airway smooth muscle strips from trachea or first generation bronchi (including small adjoining segments of the cartilaginous ring) were used rather than intact rings.

Guinea pig tracheal rings.

All animal protocols were approved by the Columbia University Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Hartley guinea pigs were euthanized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital. Trachea were surgically removed and promptly placed in cold (4°C) phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Under a dissecting microscope, closed tracheal rings including two to three cartilaginous rings were cut and separated into two groups (epithelium intact or epithelium denuded) and placed into cold Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer (in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 0.24 MgSO4, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4). Removal of epithelium was achieved by gentle mechanical rubbing of the luminal surface with cotton.

Real-time RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from human airway smooth muscle and epithelium by using the micro scale RNA isolation kit (Ambion AM1931), and cDNA was generated by reverse transcription of 2 μg of total RNA by using the Super Script VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer's recommendations. Subsequent quantitative PCR was directed against human GAD isoforms 65 and 67 (the two enzyme variants responsible for generating GABA) using gene specific primers designed to span introns to avoid confounding amplification of genomic DNA (0.4 μM of both sense and antisense; Table 1) combined with 100 ng of cDNA in a 20-μl reaction mixture using Applied Biosystems Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Life Technologies). RNA from human brain served as positive controls and samples devoid of input cDNA (water blanks) served as negative controls. Quantitative PCR parameters included an initial denaturing step at 94°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 92°C for 15 s and 65°C for 1 min with the Applied Biosystems 7500 PCR machine. Amplification plots were obtained from Applied Biosystems software, and Ct values were calculated with means from triplicate determinations of each sample. A comparison of mRNA expression between airway epithelium (epith) and smooth muscle (ASM) was expressed as a fold change by the calculation

Table 1.

Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase Primers for RT-PCR

HPLC.

To quantitatively measure differences in secreted GABA levels between epithelium-intact airways compared with airways devoid of epithelium, HPLC was used on samples obtained from guinea pig tracheal ring segments as previously published (4). Briefly, after five buffer exchanges with PBS (to minimize any GABA release resulting from dissection confounding our measurements) epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded samples were separately placed into 500-μl volumes of KH buffer. Samples were incubated for 20 min, washed, and placed in 200 μl KH buffer and underwent no treatment or exposure to KCl (60 mM). After 45 min at 37°C, 20-μl aliquots were analyzed for eluted GABA levels by HPLC. Samples underwent electrochemical detection after precolumn amino acid derivatization with o-phthalaldehyde and 2-mercaptoethanol on a system consisting of a GBC model LC1150 pump (GBC Scientific Equipment, Dandenong, Australia), a Rheodyne model 9725i injector (Rheodyne, Rohnert Park, CA), and an INTRO amperometric detector (Antec, Leyden, The Netherlands) equipped with a VT-03 (Antec) electrochemical flow cell with glassy carbon working electrode and salt bridge Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a C18 column by using a mobile phase consisting of 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 50 mg/l EDTA, and 12% methanol (pH 5.2). Generation of linear standard curves with known concentrations of GABA preceded sample analysis, and intraexperimental controls were employed as described previously (4). Additionally, to gain insight into the plausible mechanisms governing GABA release we performed a parallel set of experiments utilizing four treatment groups [no treatment, KCl 60 mM, KCl 60 mM after GAT blockade with NNC 05-2090 10 μM (5 × GAT 4 IC50 of 1.4 μM) and (S)-SNAP 5114 100 μM ∼5 × IC50 GAT2 IC50 of 21 μM, and KCl 60 mM after tetrodotoxin (10 μM) pretreatment]. These conditions were chosen since high external potassium (KCl) is a known membrane depolarizer for both epithelium and airway smooth muscle cells. This depolarization has been shown by our group (24) to stimulate GABA release through GATs in both of these cell types.

Organ bath contractility.

In vitro functional studies were performed using closed guinea pig tracheal rings and human airway smooth muscle strips in organ baths. Briefly, tissues were attached inferiorly to a fixed hook and superiorly to a Grass FT03 force transducer (Grass Telefactor, West Warwick, RI) such that muscle contraction would align in the vertical plane between the anchoring hook below and transducer above to give continuous digital recordings of muscle force over time. All studies were performed in KH buffer (in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 0.24 MgSO4, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4) continuously bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. Tissues underwent preliminary contractile challenges as previously described (4, 6).

In vitro assessment of the functional contribution the presence of epithelium imparts on endogenous GABA-mediated effects on precontracted human and guinea pig airway smooth muscle tone.

To determine the relative functional importance of GABA generated by airways with intact epithelium compared with the functional effect derived from endogenous GABA released from epithelium-denuded airways, organ bath experiments were performed by examining these two groups in parallel. This was achieved by dividing harvested tissues into two groups: one in which the epithelium remained intact, and the other that underwent either cotton denuding of the epithelium (guinea pig) or fine surgical removal of the epithelium (human) from airway specimens to create the epithelium absent groups. Otherwise, all tissues were equally prepared for organ bath study as outlined above, after which an acetylcholine EC50 contraction was generated. Following stabilization of the contraction, the tonic prorelaxant effect of endogenous GABA on muscle force was assessed by treatment with a single dose of the selective GABAA channel antagonist gabazine (200 μM guinea pig, 400 μM human) (the antagonist revealing the tonic GABAergic prorelaxant effect occurring during maintenance of contraction). In each case, treatment with vehicle served as time-matched controls. Subsequent changes in airway smooth muscle force were measured 15 min after treatment and expressed as the percent of change in muscle force elicited from the plateau achieved by the preceding EC50 acetylcholine-induced contraction.

Statistical analysis.

Each experimental permutation included intraexperimental controls. Where appropriate, we employed repeated-measures one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest comparisons between appropriate groups. In cases in which only two experimental groups were being compared a paired, two-tailed Student t-test was employed. Data are presented as means ± SE; P < 0.05 in all cases was considered significant.

RESULTS

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR demonstrates a higher expression of mRNA encoding GAD 67 in human epithelium compared with human airway smooth muscle.

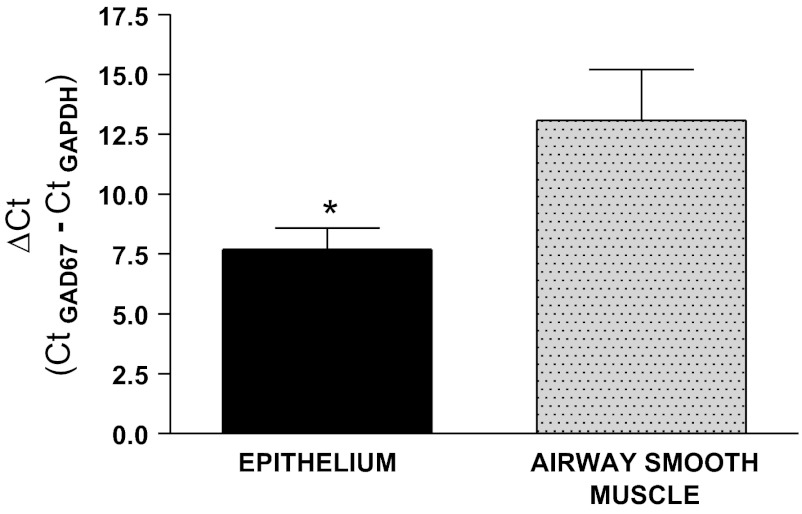

Quantitative PCR revealed no identifiable amplification of GAD 65 up to 40 cycles of PCR in both human epithelium and airway smooth muscle despite robust expression in positive controls from human brain and GAPDH expression from each sample under study (data not shown). In contrast, mRNA encoding GAD 67 was detected in both human epithelium and airway smooth muscle tissues. When correcting for each sample's expression of GAPDH (Ct of GAD67 − Ct of GAPDH), the delta Ct for GAD67 expression was significantly lower in the epithelium (indicative of higher levels of mRNA expression) compared with airway smooth muscle (epithelium ΔCt: 7.86 ± 0.89, n = 6 vs. airway smooth muscle ΔCt: 13.09 ± 2.11, n = 4, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). These differences in expression represent a 37.5-fold increase in mRNA for GAD67 in human epithelium compared with human airway smooth muscle. Each sample represents a different human patient sample.

Fig. 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR of human airway epithelium and airway smooth muscle for glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) expression. Acutely dissociated human airway epithelium (EPI) and airway smooth muscle (ASM) were analyzed for mRNA encoding GAD65 or GAD67 expression (normalized to GAPDH). GAD 65 expression was undetectable (>40 cycles, not shown), whereas GAD67 expression was higher in human EPI (ΔCt: 7.86 ± 0.89, n = 6 patient samples) compared with human ASM (ΔCt: 13.09 ± 2.11, n = 4, *P < 0.05). These differences in expression represent a 37.5-fold increase in mRNA for GAD67 in human epithelium compared with human airway smooth muscle.

Eluted GABA levels demonstrate that epithelium is a major source of endogenous airway GABA under both unstimulated and KCl-depolarized conditions.

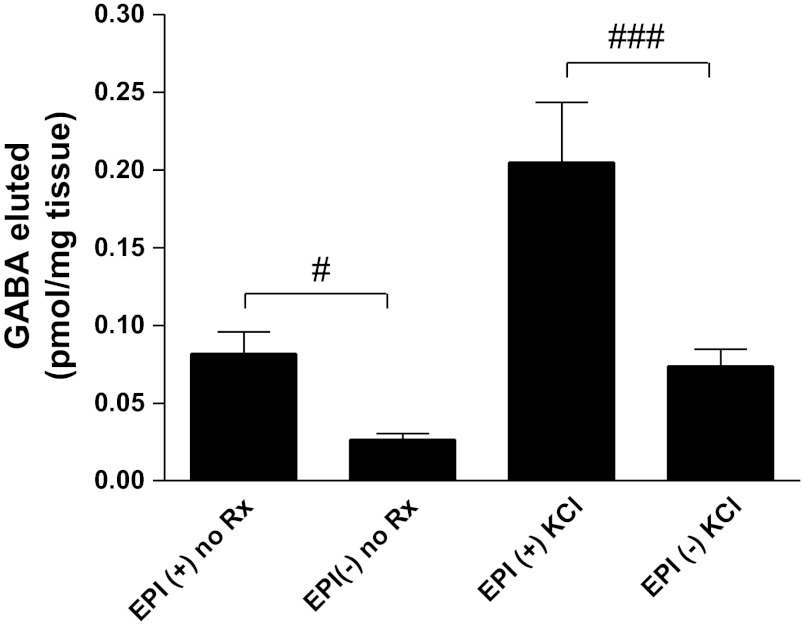

To correlate our quantitative RT-PCR findings, we assessed eluted airway GABA levels using HPLC as previously described by our group (4). Although both epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded airway tissues elaborate quantifiable levels of GABA, under both unstimulated or depolarized conditions, GABA eluted from guinea pig airway rings was significantly higher in tissues where the epithelium was intact (Fig. 2). GABA levels eluted from guinea pig airway rings maintained in KH buffer at 37°C over a 45-min period (unstimulated) are demonstrably higher from tissues with an intact epithelium (0.082 ± 0.014 pmol/mg tissue, n = 11) compared with samples where the epithelium was denuded (0.026 ± 0.004 pmol/mg tissue, n = 11; P < 0.05). Similarly, if the tissues were exposed to the depolarizing agonist KCl (60 mM) followed by a 45-min (37°C) incubation period, there is considerably more GABA eluted from the tissues where the epithelium is present (0.205 ± 0.038 pmol/mg tissue, n = 11) compared with guinea pig airway rings that are epithelium denuded (0.074 ± 0.010 pmol/mg tissue, n = 11; P < 0.001). Interestingly, the percentage of GABA attributable to an epithelial source accounts for approximately two-thirds of the total eluted GABA measured from an intact airway, with this ratio holding constant under both unstimulated and KCl-depolarized conditions.

Fig. 2.

Quantification of eluted GABA from epithelium-intact and -denuded guinea pig airways under baseline and KCl-depolarized conditions. Under both unstimulated conditions (no Rx) and in airway samples stimulated with 60 mM KCl (KCl), significantly more GABA was eluted in the presence of airway epithelium (EPI+) compared with epithelium-denuded samples (EPI−). #P < 0.05, n = 11, ###P < 0.001, n = 11.

Airway GABA release in response to depolarizing KCl treatment is GAT-mediated.

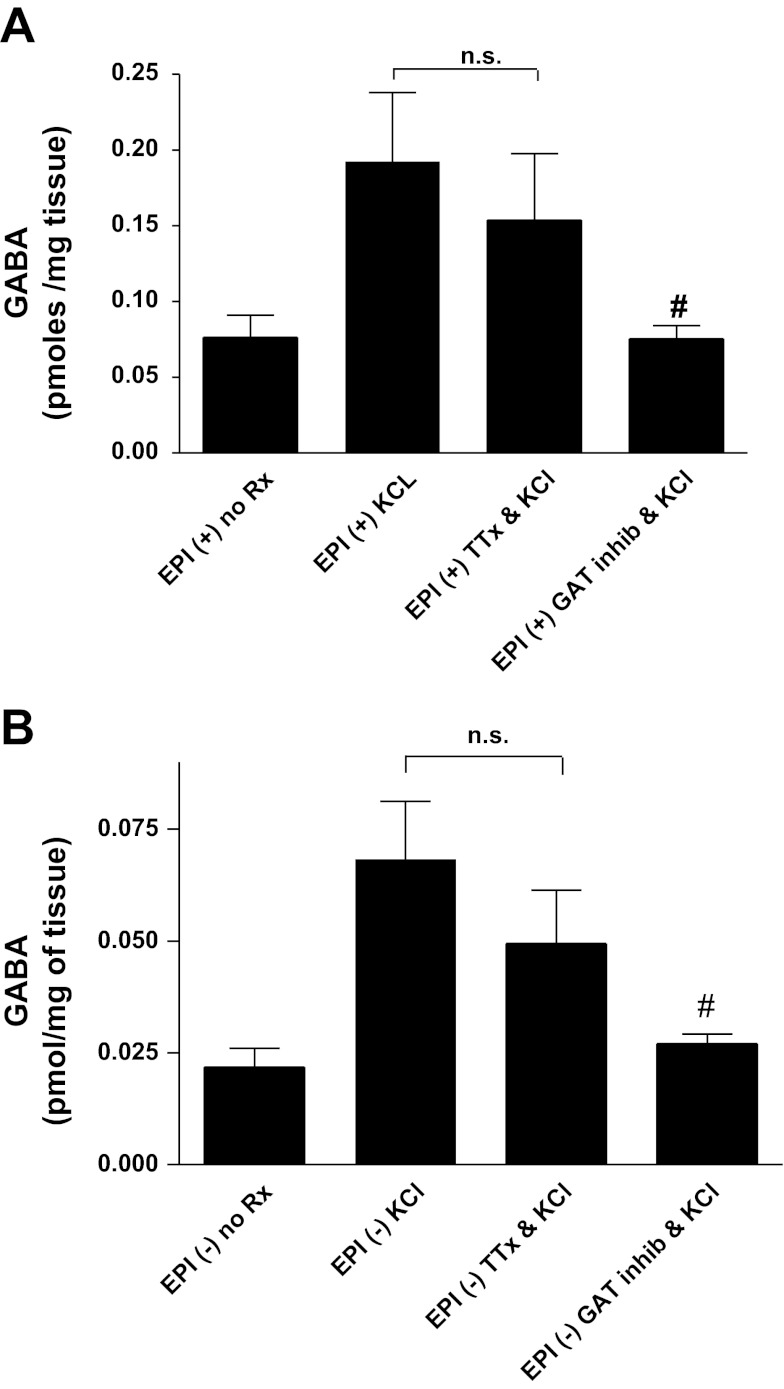

We have previously shown that GABA transporters (GAT2 and GAT4) are expressed in both cultured epithelial cells and cultured airway smooth muscle cells and participate in GABA uptake and release under depolarizing stimuli (24). To illustrate that the KCl-mediated elevations in GABA we observed were indeed GAT mediated and did not represent merely GABA release from airway nerves, we performed the above experiments in separate tissues in the presence and absence of a cocktail of GAT inhibitors [NNC 05-2090 10 μM and (S)-SNAP 5114 100 μM] or the sodium channel inhibitor tetrodotoxin (1 μM). HPLC confirmed that GAT inhibition significantly suppressed KCl-mediated release of GABA from epithelium-intact airway rings [0.075 ± 0.009 pmol/mg tissue (n = 9) vs. 0.192 ± 0.046 pmol/mg tissue (n = 9), respectively; P < 0.05], but showed no significant attenuation by tetrodotoxin pretreatment [0.154 ± 0.044 pmol/mg tissue (n = 9) vs. 0.192 ± 0.046 pmol/mg tissue (n = 9), respectively; P > 0.05] (Fig. 3A). Similar results were also obtained from epithelium-denuded rings, where GAT inhibition significantly suppressed KCl-mediated release of GABA from those tissues [0.027 ± 0.003 pmol/mg tissue (n = 7) vs. 0.068 ± 0.013 pmol/mg tissue (n = 9), respectively; P < 0.05], and tetrodotoxin treatment yielded no appreciable effect [0.049 ± 0.012 pmol/mg tissue (n = 6) vs. 0.068 ± 0.013 pmol/mg tissue (n = 9), respectively; P > 0.05] (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Quantification of eluted airway GABA demonstrates that GABA release from airway epithelium is mediated by GABA transporters but not airway nerves. A: in epithelium-intact airway rings (EPI+), KCl-induced depolarization significantly increased eluted GABA release compared with unstimulated controls (no Rx). Treatment with tetrodotoxin (TTX: to inhibit GABA release from airway nerves) in the presence of KCl had no effect on KCl-induced GABA release. Conversely, the GABA transporter-inhibitor [GAT inhib; cocktail consisting of 10 μM NNC 05-2090 and 100 μM (S)-SNAP 5114] attenuated the KCl-induced GABA release and approximated that of unstimulated controls. #P < 0.05 compared with KCl; n.s., not significant; n = 9. B: in epithelium-denuded airway rings (EPI−), a similar relationship was observed as was seen in the epithelium-intact samples (A); however, the absolute eluted GABA release was significantly decreased in EPI tissues. The GAT-inhibitor cocktail, but not TTX, significantly decreased GABA release in KCl-stimulated tissues and approximated that of unstimulated, epithelium-denuded controls. #P < 0.05 compared with KCl, n = 9.

GABAA antagonism reveals a tonic prorelaxant effect of endogenous GABA in acetylcholine contracted airways with intact epithelium.

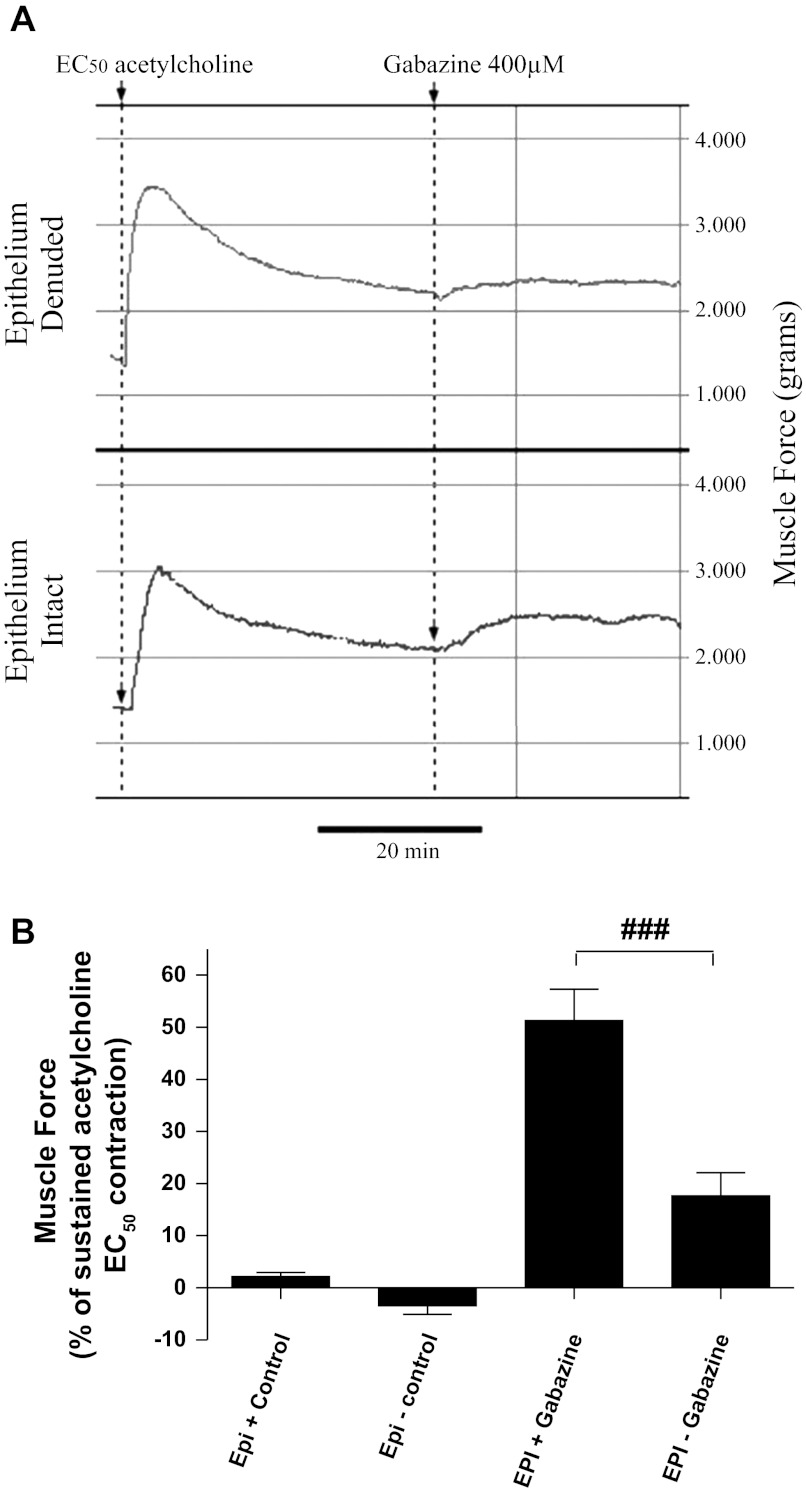

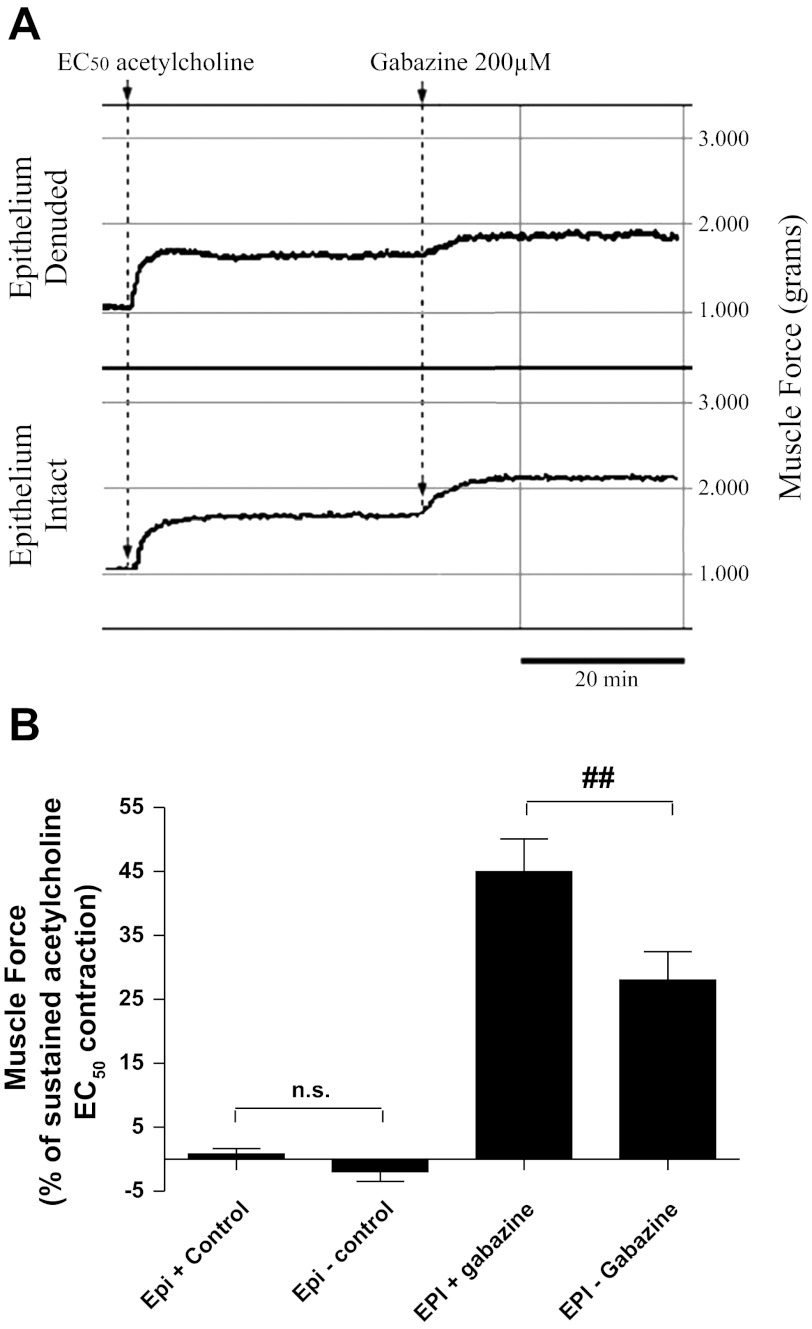

We have previously shown the functional contribution that endogenous airway GABA exerts on counterbalancing procontractile agonist-mediated contractions (4, 5). This is illustrated during the maintenance of a contraction by blocking the prorelaxant effect that GABA exerts on airway smooth muscle via GABAA receptor antagonism. In this study, we employed this physiological observation to assess the magnitude by which GABA elaborated from airway epithelium contributes to the prorelaxant tone elicited after contraction with acetylcholine. During the maintenance phase of an acetylcholine contraction, GABAA receptor antagonism with gabazine resulted in an increase in airway tension in both epithelium-intact and denuded preparations from both human (Fig. 4) and guinea pig (Fig. 5). The increase in force was more pronounced in the epithelium-intact preparations (Figs. 4A and 5A) compared with epithelium-denuded tissues (Figs. 4B and 5B), indicating a larger contribution of prorelaxant GABA signaling in the epithelium-intact group. In human upper airway tissues, GABAA channel blockade resulted in a more pronounced rise in contractile tone when the epithelium was present (51.3 ± 6.1%; n = 11) than was observed in tissues where the epithelium was removed (17.7 ± 4.4%; n = 12; P < 0.001; Fig. 4B). Similarly, in guinea pig tracheal rings, the presence of epithelium conferred enhanced GABAA-mediated prorelaxant tone following an EC50 acetylcholine contraction (45.0 ± 5.1%; n = 12) than was observed when the epithelium was removed (28.0 ± 4.4%; n = 12; P < 0.01; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

GABAA receptor blockade increases force in human airways contracted with acetylcholine. A: representative force tracing of human airway tissue contracted with acetylcholine (ACh). GABAA receptor antagonism (gabazine; 400 μM) results in an increase in tone in both epithelium-denuded (top) and epithelium-intact (bottom). B: the magnitude of the increase in tone, expressed as a percentage of ACh-induced contraction, is greater in the epithelium-intact preparation (EPI+) (51.3 ± 6.1%; n = 11) compared with the denuded tissue (EPI−) (17.7 ± 4.4%; n = 12). ###P < 0.001.

Fig. 5.

The GABAA receptor antagonist gabazine unmasks the tonic prorelaxant contribution of endogenous GABA to the maintenance of smooth muscle force in precontracted guinea pig tissues. A: representative force tracings of guinea pig tracheal rings contracted with acetylcholine (EC50) in epithelium-intact (top) vs. epithelium-denuded (bottom) preparations illustrating a greater increase in force in the epithelium-intact tissues. B: the magnitude of force generated following blockade GABAA receptor is greater in epithelium-intact (45.0 ± 5.1%; n = 12) compared with epithelium-denuded (28.0 ± 4.4%; n = 12) airways. ##P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study are that 1) endogenous GABA is synthesized by GAD67 in the airway, 2) GABA is predominantly derived from the airway epithelium, 3) GABA release is regulated by GAT transporters, and 4) GABA elaborated from the airway works in both an autocrine (epithelium) and paracrine (smooth muscle) fashion on airway smooth muscle to balance muscle tone during an acetylcholine-induced contraction.

Although we and others have characterized GABA effects on smooth muscle relaxation as well as GABA receptor expression in human airway (4, 7, 15, 23), we are the first to investigate the source of GABA in the airway as illustrated in the present study. Three possible sources of GABA include airway epithelium, airway smooth muscle itself, and airway nerves. In this study we focused on the potential endogenous sources of GABA from the airway smooth muscle and epithelium and quantified the relative contribution of each in modulating airway tone. To demonstrate the relative input different tissues contribute to the total pool of GABA in the airway we first chose to look at the relative abundance of mRNA encoding the two isoforms of the enzyme responsible for GABA synthesis, GAD65 or GAD67. Using quantitative RT-PCR, we demonstrate an ∼37.5-fold greater prevalence of RNA message for GAD67 in epithelial tissue compared with airway smooth muscle. Interestingly, we detected message for only one of the two known isoforms (GAD 67) taken from several different samples of native human epithelium as well as native human airway smooth muscle. Our findings are consistent with results recently published by Wang et al. (22) that also demonstrate human epithelium taken from large and small airways is devoid of significant amounts of mRNA encoding the GAD65 isoform.

To further support our hypothesis that the differences observed for mRNA encoding GAD67 actually translate into an increase in actual airway GABA levels, we employed HPLC to show that the majority of GABA that elutes from guinea pig airway tissues at baseline and under KCl depolarization is derived from the epithelium. Membrane depolarization with KCl has been associated with increased GABA release from rat cerebrocortex (17) and the enteric nervous system (ENS) from guinea pig (1, 18); however, we are the first to compare GABA eluted from endogenous airway tissues under basal and stimulated conditions. Additionally, GABA release from the ENS was shown to be tetrodotoxin sensitive (21). In this study we describe the novel tetrodotoxin-insensitive GABA release from airway tissues that is mediated via GATs, further confirming that the GABA eluted from these airways is likely not due to airway nerves. We feel it is important to recognize that our findings represent GABA that has eluted into the buffer and as such is not a direct tissue measurement. The concentrations of GABA we report are likely much lower compared with concentrations likely achieved within airway tissue. Similarly, given that KCl-mediated elevations in tone in functional organ bath studies do not occur instantaneously (and often require 20 min to reach maximal tone), our choice of 45 min seems consistent with a time point that allows both maximal mediated KCl effects and sufficient time for GABA to elute out into the buffer from within the tissue.

Consistent with our HPLC data in which epithelium-devoid tissues demonstrate markedly reduced GABA levels, we observed a correlation between the magnitude of functional GABA-mediated relaxation and the presence or absence of epithelium. Gabazine blockade of GABA-mediated relaxation resulted in increases in force in both human and guinea pig smooth muscle preparations that had epithelium intact. The magnitude in the increase in force was proportional to the amount of GABA eluted from the epithelium and airway smooth muscle. The epithelium-intact preparations had a greater increase in force upon GABAA receptor blockade, suggesting a greater endogenous GABA signaling mechanism in these tissues. Taken together our data suggests reductions in GABA translate into a quantifiable functional increase in airway force and attenuation of an endogenous paracrine relationship, whereby GABA elaborated by the epithelium serves as a prorelaxant molecule on airway smooth muscle and exerts a counterbalancing force against the procontractile mechanisms during the maintenance phase of an acetylcholine-mediated airway smooth muscle contraction.

Although airway smooth muscle contractility is a hallmark of airway diseases including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, increased airway inflammation, remodeling, and mucus production are also widely associated with these diseases. Recently, Xiang et al. (23) showed that GABAergic paracrine signaling in airway epithelium played an essential role in asthma pathogenesis by examining the role of GABA receptor and GAD expression in a mouse model of allergic asthma. We found that paracrine GABA signaling between the airway epithelium and airway smooth muscle was prorelaxant, whereas Xiang et al. found an increase in mucus production from goblet cells subsequent to allergen challenge that was mediated in part by GABA signaling in the airway epithelium. This illustrates the beneficial (smooth muscle relaxation) and potential detrimental (increased mucus production) effects associated with GABA signaling the airway and highlights the complexity of airway diseases such as asthma. It is the balance between increased airway relaxation as well as decreased inflammation, atopic immune response, and mucus secretion that will provide new therapeutic avenues in the case of airway diseases and necessitates continued research on the role of GABAergic processes in normal and disease states. One approach that has the potential for selectively targeting the beneficial effects of GABAA signaling in airway smooth muscle is to take advantage of differential GABAA receptor α-subunit expression that exists between airway smooth muscle and epithelium. Our laboratory and others have shown that human airway smooth muscle cells express α4 subunit-containing GABAA receptors whereas epithelium does not (6, 15, 23). This may be a potential clinical target since selective agonists for α4-containing GABAA receptors have recently been described (20) and we have recently shown them to be efficacious at relaxing precontracted airway smooth muscle (6). However, further studies are required to establish what airway physiological effects occur when targeting GABAA receptors containing α4 vs. α5 subunits in terms of the balance between airway smooth muscle relaxation, epithelial mucus production, inflammation, and other immune responses.

In summary, we are the first to categorize and quantify endogenous sources of GABA from the airway smooth muscle and airway epithelium. Additionally, we have demonstrated a functional role of GABAA receptor activation in counteracting an acetylcholine-induced contraction, suggesting that 1) increased airway reactivity in asthma pathogenesis may represent aberrant paracrine GABA signaling from a dysfunctional airway epithelium, and 2) selective GABAA receptor ligands may provide a novel therapeutic avenue in the treatment of airway diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grants GM065281 (C. W. Emala) and GM093137 (G. Gallos).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.G., P.Y., D.X., M.B., and C.W.E. conception and design of research; G.G., L.V., Y.Z., and D.X. performed experiments; G.G., E.A.T., P.Y., L.V., Y.Z., and C.W.E. analyzed data; G.G., E.A.T., P.Y., D.X., and C.W.E. interpreted results of experiments; G.G. prepared figures; G.G. and L.V. drafted manuscript; G.G., E.A.T., P.Y., and C.W.E. edited and revised manuscript; G.G., E.A.T., P.Y., L.V., Y.Z., D.X., M.B., and C.W.E. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bouhours B, Trigo FF, Marty A. Somatic depolarization enhances GABA release in cerebellar interneurons via a calcium/protein kinase C pathway. J Neurosci 31: 5804–5815, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chapman RW, Danko G, Rizzo C, Egan RW, Mauser PJ, Kreutner W. Prejunctional GABA-B inhibition of cholinergic, neurally-mediated airway contractions in guinea-pigs. Pulm Pharmacol 4: 218–224, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fu XW, Wood K, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure increases GABA signaling and mucin expression in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 44: 222–229, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gallos G, Gleason NR, Virag L, Zhang Y, Mizuta K, Whittington RA, Emala CW. Endogenous gamma-aminobutyric acid modulates tonic guinea pig airway tone and propofol-induced airway smooth muscle relaxation. Anesthesiology 110: 748–758, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gallos G, Gleason NR, Zhang Y, Pak SW, Sonett JR, Yang J, Emala CW. Activation of endogenous GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle potentiates isoproterenol mediated relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L1040–L1047, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gallos G, Yim P, Chang S, Zhang Y, Xu D, Cook JM, Gerthoffer WT, Emala CW., Sr Targeting the restricted α-subunit repertoire of airway smooth muscle GABAA receptors augments airway smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L248–L256, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gleason NR, Gallos G, Zhang Y, Emala CW. The GABAA agonist muscimol attenuates induced airway constriction in guinea pigs in vivo. J Appl Physiol 106: 1257–1263, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holgate ST. The sentinel role of the airway epithelium in asthma pathogenesis. Immunol Rev 242: 205–219, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holgate ST, Roberts G, Arshad HS, Howarth PH, Davies DE. The role of the airway epithelium and its interaction with environmental factors in asthma pathogenesis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 6: 655–659, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kleinstiver PW, Eyre P. The lung parenchyma strip preparation of the cat and dog: responses to anaphylactic mediators and sympathetic bronchodilators. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 27: 451–467, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuo PL, Hsu YL, Huang MS, Chiang SL, Ko YC. Bronchial epithelium-derived IL-8 and RANTES increased bronchial smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation by Kruppel-like factor 5 in areca nut-mediated airway remodeling. Toxicol Sci 121: 177–190, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le Cras TD, Acciani TH, Mushaben EM, Kramer EL, Pastura PA, Hardie WD, Korfhagen TR, Sivaprasad U, Ericksen M, Gibson AM, Holtzman MJ, Whitsett JA, Hershey GK. Epithelial EGF receptor signaling mediates airway hyperreactivity and remodeling in a mouse model of chronic asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L414–L421, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin DL, Rimvall K. Regulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid synthesis in the brain. J Neurochem 60: 395–407, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mizuta K, Osawa Y, Mizuta F, Xu D, Emala CW. Functional expression of GABAB receptors in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 39: 296–304, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mizuta K, Xu D, Pan Y, Comas G, Sonett JR, Zhang Y, Panettieri RA, Jr, Yang J, Emala CW., Sr GABAA receptors are expressed and facilitate relaxation in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L1206–L1216, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osawa Y, Xu D, Sternberg D, Sonett JR, D'Armiento J, Panettieri RA, Emala CW. Functional expression of the GABAB receptor in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L923–L931, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raiteri L, Stigliani S, Zedda L, Raiteri M, Bonanno G. Multiple mechanisms of transmitter release evoked by “pathologically” elevated extracellular [K+]: involvement of transporter reversal and mitochondrial calcium. J Neurochem 80: 706–714, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reis HJ, Biscaro FV, Gomez MV, Romano-Silva MA. Depolarization-evoked GABA release from myenteric plexus is partially coupled to L-, N-, and P/Q-type calcium channels. Cell Mol Neurobiol 22: 805–811, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rengasamy A, Xue C, Johns RA. Immunohistochemical demonstration of a paracrine role of nitric oxide in bronchial function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 267: L704–L711, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rivas FM, Stables JP, Murphree L, Edwankar RV, Edwankar CR, Huang S, Jain HD, Zhou H, Majumder S, Sankar S, Roth BL, Ramerstorfer J, Furtmuller R, Sieghart W, Cook JM. Antiseizure activity of novel γ-aminobutyric acid (A) receptor subtype-selective benzodiazepine analogs in mice and rat models. J Med Chem 52: 1795–1798, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taniyama K, Kusunoki M, Saito N, Tanaka C. [Release of gamma-aminobutyric acid from cat colon]. Science 217: 1038–1040, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang G, Wang R, Ferris B, Salit J, Strulovici-Barel Y, Hackett NR, Crystal RG. Smoking-mediated up-regulation of GAD67 expression in the human airway epithelium. Respir Res 11: 150, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xiang YY, Wang S, Liu M, Hirota JA, Li J, Ju W, Fan Y, Kelly MM, Ye B, Orser B, O'Byrne PM, Inman MD, Yang X, Lu WY. A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med 13: 862–867, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zaidi S, Gallos G, Yim PD, Xu D, Sonett JR, Panettieri RA, Jr, Gerthoffer W, Emala CW. Functional expression of GABA transporter 2 in human and guinea pig airway epithelium and smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 45: 332–339, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]