Abstract

Despite changes in the epidemiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia [BPD], longer term morbidity, particularly in the form of airway dysfunction, remains a substantial problem in former preterm infants. The stage for this respiratory morbidity may begin as early as the transition from fetal to neonatal life. Newer therapeutic approaches for BPD should be directed toward minimizing this longer term respiratory morbidity. Neonatal animal models focused primarily on hyperoxic exposure may provide important insights into the pathogenesis of longer term airway hyperreactivity in this population.

Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, neonatal airway function, pediatric asthma

The Spectrum of Neonatal Lung and Airway Injury

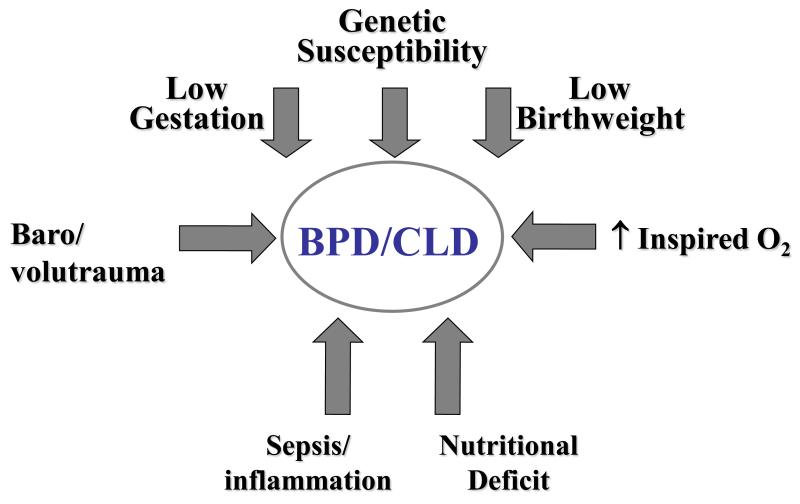

It is 45 years since Northway and colleagues first coined the term “bronchopulmonary dysplasia” [BPD] to describe a chronic form of neonatal lung injury associated with delivery of barotrauma to a group of preterm infants [1]. Over the ensuing decades the spectrum of disease has changed and the emphasis has moved away from baro- or even volutrauma as fundamental to its etiology. Nonetheless, the etiology remains multifactorial as summarized in Figure 1. While the low gestation associated with an underdeveloped lung is the key ingredient of BPD, pathobiology is clearly aggravated by the presence of intrauterine growth restriction, supplemental oxygen exposure, pre- and postnatal proinflammatory mechanisms and nutritional deficits compromising lung maturation and repair [2,3]. Early evidence also points to a genetic predisposition, the basis of which still needs to be unraveled [4,5].

Figure 1.

An overview of the major multifactorial factors contributing to the genesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia [BPD] or chronic lung disease [CLD] of the neonate.

During embryogenesis airway branching plays a central role in lung development. Nonetheless, over the last decade the focus of research in BPD has been on impaired alveolar development resulting in larger, “simplified” alveolar structures [6]. This line of investigation has been complemented by novel studies demonstrating an important role for intrapulmonary vascular structures and downstream signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] on lung parenchymal development [7]. Available outcome data suggest a later reduction in pulmonary diffusing capacity, reflecting a decrease in gas transfer across the alveolar/capillary unit and possibly abnormal lung parenchyma in the low birth weight survivors of BPD [8]. At the same time there has been increasing recognition that the epidemiology of BPD has changed considerably, placing at risk extremely low birth weight infants exposed to no or minimal barotrauma and to relatively low levels of supplemental oxygen over the first days of life. Such infants may develop respiratory deterioration as late as one to two weeks postnatally, and a proinflammatory process is often implicated in this downhill progression to BPD [9].

The pathobiology of injury to the immature airway has taken somewhat of a backseat to unraveling the signaling pathways that regulate aberrant alveolar development. While traumatic injury to structurally immature, compliant airway structures is well described as a result of ventilator-induced lung injury, this problem is probably diminished by decreased use of intermittent positive pressure ventilation. On the other hand, asthma and wheezing disorders manifest by increased airway reactivity are the major longer term respiratory morbidities demonstrated by former preterm infants. Lung parenchymal structures and intrapulmonary airways are anatomically closely interrelated such that parenchymal damage may decrease the tethering between airways and lung parenchyma and compromise airway caliber [10]. This review will focus primarily on the pathophysiology of lung injury as it affects airway function, recognizing that such injury may begin as early as during the fetal to neonatal transition.

Optimizing the Fetal to Neonatal Respiratory Transition

a. Oxygen

There is considerable current interest in enhancing an effective fetal to neonatal respiratory transition while avoiding short or potential longer term injury with therapeutic interventions imposed on preterm infants. The use and abuse of supplemental oxygen immediately after delivery has attracted great interest [11]. We are indebted to Saugstad and Vento for drawing attention to the hazards of supplemental oxygen at this vulnerable period in the immature infant. Hyperoxia at this time has been shown to delay the onset of spontaneous respiratory efforts and potentially lead to unnecessary subsequent interventions. More importantly, brief but excessive oxygen exposure may result in greater expression of reactive oxygen species and oxidant-induced impairment of metabolic function. This may be caused by exposure of the airway epithelium to excessive supplemental oxygen with potential adverse effects on airway-related signaling pathways. Systemic effects may also come into play as demonstrated by elevated markers of both oxidant and inflammatory stress in blood and urine of high compared to low oxygen-exposed infants [12]. A provocative single center study demonstrated that initially high compared to low supplemental oxygen exposure after delivery may be associated with a greater need for ventilatory support and a higher subsequent incidence of BPD [12]. This has spawned a series of blinded multicenter studies to further evaluate both optimal practice [concentration of blended oxygen accompanied by pulse oximetry] and outcome [focused on BPD] with regard to initial oxygen administration for this high risk population.

b. Ventilation

In the preterm infant we seek to rapidly establish an optimal functional residual capacity [FRC] in order to support gas exchange without provoking a stretch-induced injurious cascade of lung injury. Recent studies have employed a fetal lamb model briefly ventilated in the absence of supplemental oxygen while exteriorized, then returned to the uterus prior to delivery [13]. These data provide evidence for a proinflammatory cascade and bronchial epithelial disruption initiated by just a brief period of positive ventilation in the fetal model. te Pas and colleagues have also employed animal models to determine the ability of ventilatory techniques to open the lungs and establish a FRC [14]. They have documented that a longer sustained inflation at delivery is associated with more rapid establishment of a FRC. However, the resultant rapid lung aeration and improved oxygenation must be weighed against the potential for initiating lung or airway injury.

Finally, in our attempts to minimize the need for endotracheal intubation and intermittent positive pressure ventilation, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)-based strategies have been widely studied in well designed multicenter trials [15,16]. It can be concluded from these studies that an initial CPAP-based strategy provides an effective alternative to immediate intubation and surfactant administration for many infants in the 25 to 28 weeks’ gestation range. Unfortunately, there is currently no simple bedside test or biomarker to determine which very preterm infants are likely to succeed with a CPAP-based strategy and clinical judgment must prevail as excessive delay in surfactant therapy is suboptimal.

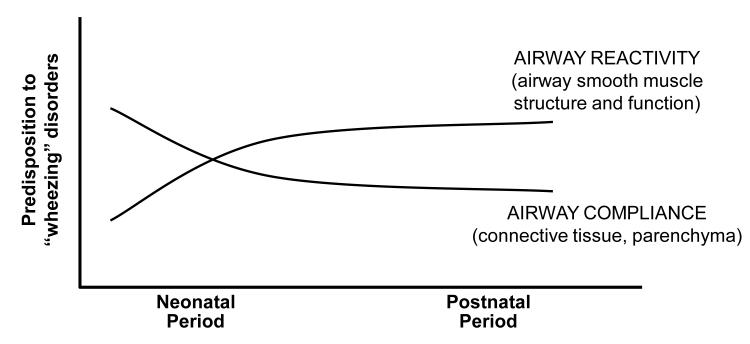

Maturation of Airway Smooth Muscle

During fetal life there is ample evidence for abundant airway smooth muscle in the developing intrapulmonary airways of both animal models and human infants [17,18]. This airway smooth muscle layer can exhibit phasic contraction and may serve a functional role in propagation of lung fluid and resultant lung development. It may also serve to provide airway stability at a time when airways have a high compliance due to paucity of cartilaginous and other connective tissue support. During postnatal maturation, and in response to neonatal lung injury [as discussed later], this balance of airway compliance and airway smooth muscle may change, predisposing to later airway hyperreactivity [Fig. 2]. This balance may also explain the failure of bronchodilator therapy to consistently improve lung function in preterm infants in the NICU [19]. It may be that airway smooth muscle tone is important to maintain airway caliber early in the course of BPD in these infants when there is increased airway compliance, hence a negative response to bronchodilation.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of maturational change in airway function of preterm infants during postnatal development. With advancing postnatal age we speculate that increased airway reactivity becomes dominant as airway compliance decreases with structural maturation.

Impact of Therapeutic Approaches on Lung and Airway Function

a. Inhibition of Inflammatory Mechanisms

Proinflammatory mechanisms have been widely implicated in the pathogenesis of BPD [20]. This is supported by the observation that postnatal steroid therapy enhances the ability to extubate many infants with developing lung injury, although potential benefit must be weighed against the adverse neurodevelopmental side effects of such therapy. Longer term outcome studies have focused on neurodevelopmental rather than respiratory follow-up of postnatal steroid therapy, however, if extubation is enhanced, one would expect that longer term airway function would be improved. There is still controversy regarding optimal dosing and timing of postnatal steroid therapy, and whether reduction in its use has been associated with an increase in the incidence or severity of BPD in NICU survivors [21]. Future clinical data may provide greater detail on specific cytokine mediated pathways in neonatal lung injury, thus providing a safer, more selective, approach to therapy.

b. Targeting Lung Elastase

Given the functional interdependence of lung parenchyma and intrapulmonary airways, it is important to consider experimental approaches that minimize elastin degradation in the genesis of neonatal lung injury. Earlier studies in preterm infants have demonstrated imbalance in elastase/antielastase ratios associated with neonatal lung injury [22, 23]. Recent data in mechanically ventilated neonatal mice have shown that intratracheal administration of a specific lung protease inhibitor protected against neonatal lung injury induced by a combination of mechanical ventilation and high oxygen exposure [24]. This may be a mechanism for the slight decrease in BPD observed in preterm infants treated with a prolonged course of vitamin A [25,26].

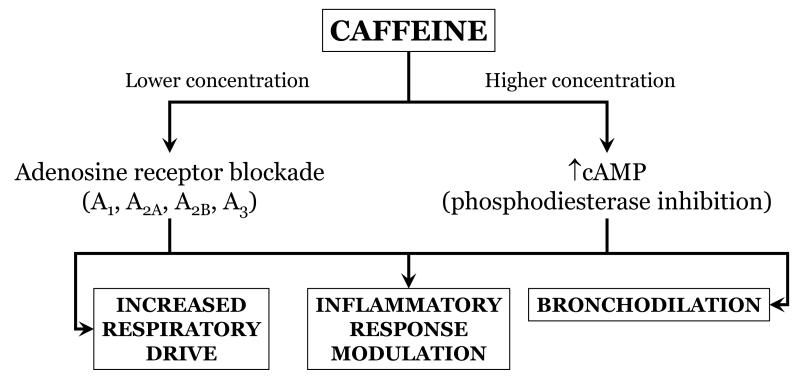

c. Caffeine Therapy

Use of xanthines [theophylline and caffeine] has been widespread for treating apnea since the 1970s. The most widely accepted mechanism of action is inhibition of adenosine receptors and resultant increase in respiratory neural output. However, xanthines also inhibit phosphodiesterase and the resultant increase in cyclic AMP may cause bronchodilation [Fig. 3]. Of relevance is the large multicenter trial performed in the last decade that demonstrated a decrease in the need for supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation in caffeine-rather than placebo-treated preterm infants [27]. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 18 to 21 months seems to favor caffeine therapy although by 5 years this is no longer so [28].

Figure 3.

Proposed beneficial effects of xanthine therapy in preterm infants at risk for BPD.

Intermittent hypoxic episodes are almost universal in preterm infants and a likely source of oxidant stress [29]. A vicious cycle of oxidant stress and proinflammatory mechanisms may contribute to lung and airway injury in this population. Therefore, antioxidant therapy might represent a novel therapeutic approach. Only one clinical trial has addressed this strategy in preterm infants [30]. Intratracheal recombinant human superoxide dismutase was administered repeatedly for up to one month but did not reduce the incidence of BPD. However, there was a significant decrease in wheezing disorders and need for bronchodilator therapy in the treated group at one year of age. Despite this encouraging result, further clinical trials are not ongoing, in part because of limited commercial pharmaceutical interest.

d. Inhaled Nitric Oxide [NO] and Airway Function

Animal models of BPD have demonstrated remarkable improvement in lung function when exposed to several weeks of inhaled NO [31]. These and other data led to great enthusiasm for this therapy as a way to decrease BPD. However, a series of large, well designed, multicenter, clinical trials failed to demonstrate a consistent benefit from inhaled NO; a consensus statement concluded that, despite biological plausibility, available data do not support its use to prevent or treat BPD [32]. Unfortunately, there was great heterogeneity in the various trials making meta-analysis a problem. One study employing a prolonged course of initially high dose NO did demonstrate a significant increase in survival without BPD in NO-treated infants [33]. Interestingly, a follow-up study of that cohort demonstrated significantly decreased use of bronchodilator therapy in the NO-treated infants at one year with a number needed to treat of 6.3 [34]. These data, again, demonstrate a potentially important role of airway function to assess neonatal outcomes.

Use of Animal Models to Evaluate Longer Term Airway Function in Response to Neonatal Interventions

One of the first documented experimental models of neonatal oxygen-induced lung injury was in mice exposed to 100% oxygen for the first seven postnatal days; the lungs developed alveolar dysplasia and fibrosis characteristic of chronic lung disease [35]. The neonatal period is essential for lung development, and several animal models have since been developed to investigate mechanisms of BPD-like lung injury, including rats, rabbits, lambs and primates [36], focused largely on signaling mechanisms of oxygen-induced lung injury. Although a number of these animal models has been crucial to our understanding of the mechanisms of injury, there is a paucity of data on the short- [and especially long-] term effects of neonatal oxygen on control of airway tone. Earlier studies on newborn guinea pigs were amongst the first to show [in vitro] increased acetylcholine- and histamine-induced contraction of airways removed from neonates [2-days old] raised in 85% oxygen [37]. The oxygen-induced airway hyperreactivity may be independent of alveolar injury and probably depends on the severity of oxygen exposure. Even earlier studies [in vivo] also showed increased cholinergic reactivity of airways from “juvenile” rats [21 days old] exposed to eight days of >95% oxygen [38]. While the mechanisms of airway hyperreactivity are still largely unknown, evidence suggests it is related, in part, to an oxygen-induced infiltration of inflammatory cells into the airways [39] and NO-dependent impairment of airway relaxation [40].

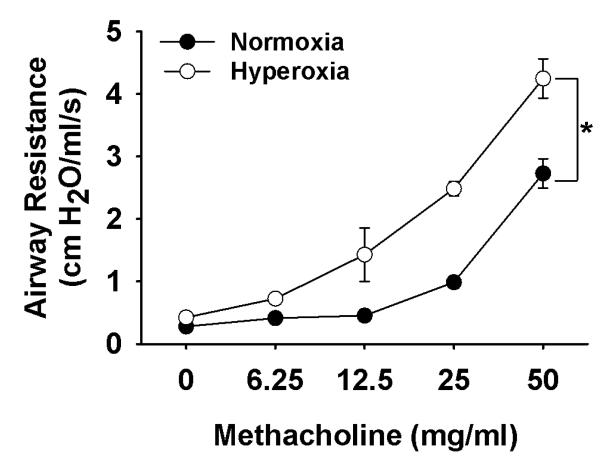

Experimental models that address longer-term effects of neonatal oxygen on airway hyperreactivity are scarce. The hyper-responsiveness of “juvenile” rat pups exposed to hyperoxia failed to persist into adulthood [41], however, this could be a consequence of age of exposure and the greater sensitivity of an immature compared to a more mature lung to oxygen. We have exposed neonatal mice from birth to four days to moderate [50%] oxygen, which resulted in an increased sensitivity [assessed by respiratory system resistance] to methacholine challenge after a further 16 days of room air [Fig. 4]. A more recent study demonstrated a persistent effect [up to 8 weeks of age] of neonatal [age 1-4 days] oxygen [ranging from 60-100% ] on airway resistance, but airway hyperreactivity was not investigated [42]. Similarly, airway resistance was also increased in newborn rats raised in 85% oxygen from birth to 14 days of age and persisted after a further 14 days in normoxia only in rats that were pre-treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in utero [43]; airway hyperreactivity again was not assessed. Collectively, these data suggest that although hyperoxia can elicit short-term and persistent changes in baseline airway function and respiratory mechanics, they may do so independently to the development of airway hyperreactivity. Overall, these data also emphasize an essential need for a worthy model of neonatal oxygen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Future study might focus on the relationship between airway function and structure in former preterm infants, and the alveolar simplification that is well described in infants with BPD.

Figure 4.

Dose-dependant effects of methacholine on respiratory system resistance in three week old anesthetized mice that received neonatal oxygen [50% O2, birth to day 4; open circles] or were raised in normoxia [solid circles]. Note that neonatal hyperoxia had no long-term effects on baseline resistance, but caused a hyperreactive response to increasing doses of methacholine [indicated by higher resistance]. Each mouse received nebulized methacholine before respiratory maneuvers were performed using a rodent ventilator [SCIREQ, flexivent].

Respiratory Morbidity in Former Preterm Infants

Recurrent wheezing is a common condition encountered by former preterm infants. Available data almost universally indicate a significant increased risk of developing asthma in former preterm as compared to term infants [44]. The association between preterm delivery and airway obstruction leading to the diagnosis of asthma later in life has been established, but the mechanisms underlying this association are not well understood. Multiple studies have demonstrated greater rates of recurrent wheezing associated with a history of BPD. Interestingly, late-preterm birth and low-normal gestational ages may also be important risk factors for the development of persistent asthma [45].

Lifelong consequences from early lung injury are reported in the literature, but the evidence becomes sparse with increasing chronological age into adulthood [46]. In addition, the advent of modern management techniques [such as antenatal steroids, surfactant therapy] has changed the risk and character of respiratory disease, thus ultimately leading to a need for newer cohorts to evaluate airway function in preterm infants. The overall impact of newer interventions on long-term pulmonary function into adulthood is clearly an ongoing challenge.

a. Prenatal and Early Life Factors on the Development of Recurrent Wheezing

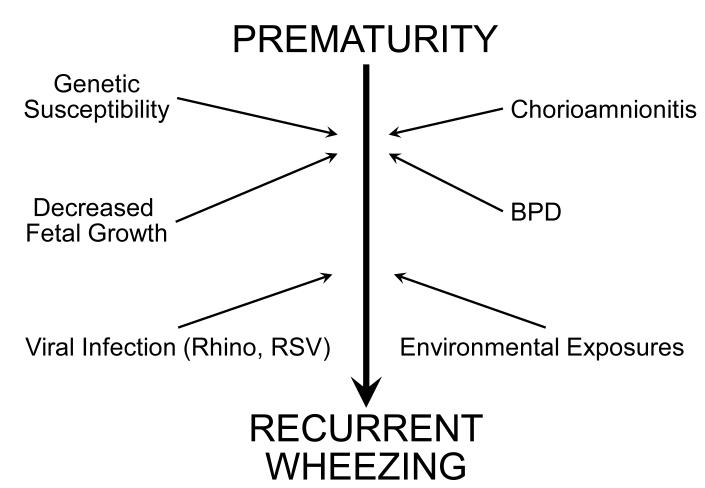

Factors that predispose preterm infants to develop recurrent wheezing may occur as early as in utero. (Fig 5) Programming and immunologic changes determined in utero may affect the risk of developing respiratory morbidity later in life [47]. Fetal growth restriction is one such probable example in which reduced lung function in early school age may be aggravated in former preterm infants who exhibit intrauterine growth restriction [48]. Chorioamnionitis, in combination with prematurity, is another such factor that may lead to early childhood recurrent wheezing [47].

Figure 5.

Risk factors for recurrent wheezing in former preterm infants.

The etiology and pathogenesis of asthma in normative populations involves both genetic risk for atopic disease and environmental exposures. Former preterm infants appear to have similar symptoms to those of term-born children with asthma, but the pathophysiology is complicated by abnormal lung development and BPD [49]. This was best demonstrated morphologically on high resolution CT scans of the chest in young adults who were born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation. Similarly to normal individuals with asthma, airway wall thickening was noted. Additionally, discrete linear or triangular opacities, together with mosaic perfusion and air trapping, were also present. These findings may represent a fixed peripheral airway narrowing [50].

Interestingly, it appears that in former preterm adolescents, the incidence of atopy is less than their term-born counterparts. This further raises the possibility that the phenotype of asthma may differ in former preterm infants from what is generally seen in term-born asthmatics [51]. Moreover, former preterm infants have decreased levels of exhaled nitric oxide, a marker for airway inflammation, compared to the elevated levels found with traditional asthmatics [52].

Extremely low birth weight [ELBW] infants who survive have higher rates of wheezing and hospital readmission for respiratory illnesses in the first few years of life than their term counterparts. Studies on term infants have shown that beyond infancy respiratory illnesses due to respiratory syncytial virus [RSV] and rhinovirus are associated with recurrent wheezing and asthma [53]. A link between viral infections [such as RSV and rhinovirus] and recurrent wheezing in former preterm infants is also likely. Additionally, rhinovirus is more commonly associated with wheeze in infants with congenital small airways, such as those born preterm [53].

b. Challenges in Evaluating Long Term Outcomes in Former Preterm Infants

Asthma is defined traditionally as bronchoconstriction that is reversible, typically with bronchodilators. When determining airway function in former preterm infants, pulmonary function testing is a generally accepted measure. Alternatively, the diagnosis of asthma may be made clinically after obtaining a detailed history of symptoms, and usage of asthma medications in the last 12 months. The diagnosis of asthma may or may not correlate with pulmonary function testing.

Recently, Hack et al. reported the prevalence of asthma based on clinical diagnosis or supportive history alone in ELBW children at 8 years of age to be significantly greater than in normal birth weight controls [39% vs 21%]. Interestingly, the difference between these two groups was no longer significant at 14 years of age, suggesting possible symptom resolution in some of the ELBW infants [54].

On the other hand, in the EPICure study, Fawke et al. investigated airway function by spirometry in 11-year old former ELBW infants. This study showed impaired lung function and increased respiratory morbidity into middle childhood [49]. These data may indicate that clinical symptoms improve gradually with advancing age during childhood, while tests of pulmonary function may or may not improve in former preterm infants. This would support the stance that the diagnosis of asthma should be documented with pulmonary function testing.

Special considerations are necessary in preterm infants with respect to preventive measures against known or suspected triggers of asthma. Former preterm infants’ triggers may be different from those in the term population. Specifically, there may be less environmental allergen involvement leading to inflammatory airway constriction [51]. Furthermore, recognition of prematurity as a determinant of asthma should prompt clinicians to actively seek out signs and symptoms of reactive airway disease for faster treatment. Treatment of children born prematurely with recurrent wheezing may be challenging. For example, response to treatment with inhaled corticosteroids is less consistent than in the normative population with asthma [55]. For all these reasons, further studies that help elucidate the pathology and clinical characteristics of airway disease in former preterm infants are imperative in establishing guidelines for early intervention and treatment options, as well as outlining long term management strategies.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH grant HL 56470 [RJ Martin, MD]

References

- 1.Northway WH, Jr, Rosan RC, Porter DY. Pulmonary disease following respirator therapy of hyaline-membrane disease. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1967;276(7):357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196702162760701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bose C, Van Marter LJ, Laughon M, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Kama P, Ehrenkranz RA, Boggess K, Leviton A. Fetal growth restriction and chronic lung disease among infants born before the 28th week of gestation. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):e450–e458. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manley BJ, Makrides M, Collins CT, McPhee AJ, Gibson RA, Ryan P, Sullivan TR, Davis PG. High-dose docosahexaenoic acid supplementation of preterm infants: respiratory and allergy outcomes. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e71–e77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavoie PM, Pham C, Jang KL. Heritability of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, defined according to the consensus statement of the national institutes of health. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):479–485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadchouel A, Durrmeyer X, Bouzigon E, Incitti R, Huusko J, Jarreau PH, Lenclen R, Demenais F, Franco-Montoya ML, Layouni I, Patkai J, Bourbon J, Hallman M, Danan C, Delacourt C. Identification of SPOCK2 as a susceptibility gene for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1164–1170. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0548OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunig AM, Balasubramaniam V, Markham NE, Morgan D, Montgomery G, Grover TR, Abman SH. Recombinant human VEGF treatment enhances alveolarization after hyperoxic lung injury in neonatal rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289(4):L529–535. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00336.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balinotti JE, Chakr VC, Tiller C, Kimmel R, Coates C, Kisling J, Yu Z, Nguyen J, Tepper RS. Growth of lung parenchyma in infants and toddlers with chronic lung disease of infancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(10):1093–1097. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1190OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laughon M, Allred EN, Bose C, O’Shea TM, Van Marter LJ, Ehrenkranz RA, Leviton A. Patterns of respiratory disease during the first 2 postnatal weeks in extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1124–1131. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colin AA, McEvoy C, Castile RG. Respiratory morbidity and lung function in preterm infants of 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):115–128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finer N, Saugstad O, Vento M, Barrington K, Davis P, Duara S, Leone T, Lui K, Martin R, Morley C, Rabi Y, Rich W. Use of oxygen for resuscitation of the extremely low birth weight infant. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):389–391. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vento M, Moro M, Escrig R, Arruza L, Villar G, Escort I, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Arden A, Escobar JJ, Sastre J, Asensi MA. Preterm resuscitation with low oxygen causes less oxidative stress, inflammation, and chronic lung disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):e439–e449. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillman NH, Polglase GR, Pillow JJ, Saito M, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH. Inflammation and lung maturation from stretch injury in preterm fetal sheep. Am J Physiol. 2011;300(2):L232–L241. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00294.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.te Pas AB, Siew M, Wallace MJ, Kitchen MJ, Fouras A, Lewis RA, Yagi N, Uesugi K, Donath S, Davis PG, Morley CJ, Hooper SB. Effect of sustained inflation length on establishing functional residual capacity at birth in ventilated premature rabbits. Pediatr Res. 2009;66(3):295–300. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181b1bca4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morley CJ, Davis PG, Doyle LW, Brion LP, Hascoet JM, Carlin JB. Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):700–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Carlo WA, Finer NN, Walsh MC, Rich W, Gantz MG, Laptook AR, Yoder BA, Faix RG, Das A, Poole WK, Schibler K, Newman NS, Ambalavanan N, Frantz ID, 3rd, Piazza AJ, Sanchez PJ, Morris BH, Laroia N, Phelps DL, Poindexter BB, Cotten CM, Van Meurs KP, Duara S, Narendran V, Sood BG, O’Shea TM, Bell EF, Ehrenkranz RA, Watterberg KL, Higgins RD. Target ranges of oxygen saturation in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1959–1969. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sparrow MP, Lamb JP. Ontogeny of airway smooth muscle: structure, innervation, myogenesis and function in the fetal lung. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;137(2-3):361–372. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sward-Comunelli SL, Mabry SM, Truog WE, Thibeault DW. Airway muscle in preterm infants: changes during development. J Pediatr. 1997;130(4):570–576. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denjean A, Paris-Llado J, Zupan V, Debillon T, Kieffer F, Magny JF, Desfreres L, Llanas B, Guimaraes H, Moriette G, Voyer M, Dehan M, Breart G. Inhaled salbutamol and beclomethasone for preventing broncho-pulmonary dysplasia: a randomised double-blind study. Euro J Pediatr. 1998;157(11):926–931. doi: 10.1007/s004310050969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Speer CP. Chorioamnionitis, postnatal factors and proinflammatory response in the pathogenetic sequence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Neonatology. 2009;95(4):353–361. doi: 10.1159/000209301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watterburg KL, Committee on Fetus and Newborn Postnatal corticosteroids to prevent or treat bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 2010;126:800–808. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce MC, Schuyler M, Martin RJ, Starcher BC, Tomashefski JF, Jr., Wedig KE. Risk factors for the degradation of lung elastic fibers in the ventilated neonate. Implications for impaired lung development in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(1):204–212. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Speer CP, Ruess D, Harms K, Herting E, Gefeller O. Neutrophil elastase and acute pulmonary damage in neonates with severe respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatrics. 1993;91(4):794–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilgendorff A, Parai K, Ertsey R, Jain N, Navarro EF, Peterson JL, Tamosiuniene R, Nicolls MR, Starcher BC, Rabinovitch M, Bland RD. Inhibiting lung elastase activity enables lung growth in mechanically ventilated newborn mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):537–546. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2010OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyson JE, Wright LL, Oh W, Kennedy KA, Mele L, Ehrenkranz RA, Stoll BJ, Lemons JA, Stevenson DK, Bauer CR, Korones SB, Fanaroff AA. Vitamin A supplementation for extremely- low- birth- weight infants. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(25):1962–1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albertine KH, Dahl MJ, Gonzales LW, Wang ZM, Metcalfe D, Hyde DM, Plopper CG, Starcher BC, Carlton DP, Bland RD. Chronic lung disease in preterm lambs: effect of daily vitamin A treatment on alveolarization. Am J Physiol. 2010;299(1):L59–72. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00380.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, Solimano A, Tin W. Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(20):2112–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt B, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW, Dewey D, Grunau RE, Asztalos EV, Davis PG, Tin W, Moddemann D, Solimano A, Ohlsson A, Barrington KJ, Roberts RS, Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) Trial Investigators Survival without disability to age 5 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. JAMA. 2012;307(3):275–282. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin R, Wang K, Köro□lu Ö , Di Fiore J, Kc P. Intermittent hypoxic episodes in preterm infants: do they matter? Neonatology. 2011;100(3):303–310. doi: 10.1159/000329922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis JM, Parad RB, Michele T, Allred E, Price A, Rosenfeld W. Pulmonary outcome at 1 year corrected age in premature infants treated at birth with recombinant human CuZn superoxide dismutase. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):469–476. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCurnin DC, Pierce RA, Chang LY, Gibson LL, Osborne-Lawrence S, Yoder BA, Kerecman JD, Albertine KH, Winter VT, Coalson JJ, Crapo JD, Grubb PH, Shaul PW. Inhaled NO improves early pulmonary function and modifies lung growth and elastin deposition in a baboon model of neonatal chronic lung disease. Am J Physiol. 2005;288(3):L450–459. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00347.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole FS, Alleyne C, Barks JD, Boyle RJ, Carroll JL, Dokken D, Edwards WH, Georgieff M, Gregory K, Johnston MV, Kramer M, Mitchell C, Neu J, Pursley DM, Robinson WM, Rowitch DH. NIH Consensus Development Conference statement: inhaled nitric-oxide therapy for premature infants. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):363–369. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballard RA, Truog WE, Cnaan A, Martin RJ, Ballard PL, Merrill JD, Walsh MC, Durand DJ, Mayock DE, Eichenwald EC, Null DR, Hudak ML, Puri AR, Golombek SG, Courtney SE, Stewart DL, Welty SE, Phibbs RH, Hibbs AM, Luan X, Wadlinger SR, Asselin JM, Coburn CE. Inhaled nitric oxide in preterm infants undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):343–353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hibbs AM, Walsh MC, Martin RJ, Truog WE, Lorch SA, Alessandrini E, Cnaan A, Palermo L, Wadlinger SR, Coburn CE, Ballard PL, Ballard RA. One-year respiratory outcomes of preterm infants enrolled in the nitric oxide (to prevent) chronic lung disease trial. J Pediatr. 2008;153(4):525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonikos DS, Bensch KG, Ludwin SK, Northway WH., Jr Oxygen toxicity in the newborn. The effect of prolonged 100 per cent O2 exposure on the lungs of newborn mice. Lab Invest. 1975;32(5):619–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warner BB, Stuart LA, Papes RA, Wispe JR. Functional and pathological effects of prolonged hyperoxia in neonatal mice. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275(1 Pt 1):L110–117. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.1.L110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uyehara CF, Pichoff BE, Sim HH, Uemura HS, Nakamura KT. Hyperoxic exposure enhances airway reactivity of newborn guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74(6):2649–2654. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershenson MB, Garland A, Kelleher MD, Zimmermann A, Hernandez C, Solway J. Hyperoxia-induced airway remodeling in immature rats. Correlation with airway responsiveness. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(5 Pt 1):1294–1300. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_1.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denis D, Fayon MJ, Berger P, Molimard M, De Lara MT, Roux E, Marthan R. Prolonged moderate hyperoxia induces hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation in newborn rats. Pediatr Res. 2001;50(4):515–519. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200110000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali NK, Jafri A, Sopi RB, Prakash YS, Martin RJ, Zaidi SI. Role of arginase in impairing relaxation of lung parenchyma of hyperoxia-exposed neonatal rats. Neonatology. 2011;101(2):106–115. doi: 10.1159/000329540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hershenson MB, Abe MK, Kelleher MD, Naureckas ET, Garland A, Zimmermann A, Rubinstein VJ, Solway J. Recovery of airway structure and function after hyperoxic exposure in immature rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(6):1663–1669. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yee M, Chess PR, McGrath-Morrow SA, Wang Z, Gelein R, Zhou R, Dean DA, Notter RH, O’Reilly MA. Neonatal oxygen adversely affects lung function in adult mice without altering surfactant composition or activity. Am J Physiol. 2009;297(4):L641–649. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00023.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velten M, Heyob KM, Rogers LK, Welty SE. Deficits in lung alveolarization and function after systemic maternal inflammation and neonatal hyperoxia exposure. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):1347–1356. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01392.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaakkola JJK, Ahmed P, Ieromnimon A, Goepfert P, Laiou E, Quansah R, Jaakkola MS. Preterm delivery and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:823–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goyal NK, Fiks AG, Lorch SA. Association of late-preterm birth with asthma in young children: practice-based study. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):e830–e838. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walter EC, Ehlenbach WJ, Hotchkin DL, Chien JW, Koepsell TD. Low birth weight and respiratory disease in adulthood: a population-based case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(2):176–180. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0046OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar R, Yu Y, Story RE, Pongracic JA, Gupta R, Pearson C, Ortiz K, Bauchner HC, Wang X. Prematurity, chorioamnionitis, and the development of recurrent wheezing: a prospective birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(4):878–884. e876. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morsing E, Gustafsson P, Brodszki J. Lung function in children born after foetal growth restriction and very preterm birth. Acta Paediatr. 2011;101(1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fawke J, Lum S, Kirkby J, Hennessy E, Marlow N, Rowell V, Thomas S, Stocks J. Lung function and respiratory symptoms at 11 years in children born extremely preterm: the EPICure study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):237–245. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1806OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aukland SM, Halvorsen T, Fosse KR, Daltveit AK, Rosendahl K. High-resolution CT of the chest in children and young adults who were born prematurely: findings in a population-based study. AJR. 2006;187(4):1012–1018. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siltanen M, Wehkalampi K, Hovi P, Eriksson JG, Strang-Karlsson S, Jarvenpaa AL, Andersson S, Kajantie E. Preterm birth reduces the incidence of atopy in adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(4):935–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baraldi E, Bonetto G, Zacchello F, Filippone M. Low exhaled nitric oxide in school-age children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(1):68–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-298OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Zalm MM, Uiterwaal CS, Wilbrink B, Koopman M, Verheij TJ, van der Ent CK. The influence of neonatal lung function on rhinovirus-associated wheeze. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(2):262–267. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0716OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hack M, Schluchter M, Andreias L, Margevicius S, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Cuttler L. Change in prevalence of chronic conditions between childhood and adolescence among extremely low-birth-weight children. JAMA. 2011;306(4):394–401. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelkonen AS, Hakulinen AL, Hallman M, Turpeinen M. Effect of inhaled budesonide therapy on lung function in schoolchildren born preterm. Respir Med. 2001;95(7):565–570. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]