Abstract

Background: In late 2005, the federal and provincial governments responded to an increasing demand from physicians and their patients with Fabry disease for access to enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). This response took the form of a nationwide clinical research study, the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI). Patients who enrolled as participants in this longitudinal study received 1 of 2 ERT treatments. The present study used a qualitative evaluative approach to describe the perspectives of various key stakeholders regarding the CFDI and its potential as a model for providing access to expensive drugs for rare diseases.

Methods: The CFDI was evaluated from the perspectives of 4 groups of key informants: patients, CFDI investigators, policy-makers and pharmaceutical manufacturers. The qualitative methods strategy used for the study involved semistructured interviews, a holistic-inductive design and content analysis.

Results: Eighteen participants were interviewed. The study revealed that stakeholders held the following perceptions about the CFDI. The CFDI was created as a response to a drug reimbursement problem in Canada. Through specialist physicians, the CFDI has provided ERT to patients with Fabry disease across the country. The CFDI established a national database for collecting and monitoring the incidence of Fabry disease and information about ERT. The CFDI represented a collaborative effort among the various stakeholders (federal, provincial, pharmaceutical), but no stakeholder group thought that the CFDI was the correct response to the need for access to ERT. Finally, the CFDI can and should be redesigned, through modification of either its governing structure or its outcome goals.

Discussion: The CFDI was a prototype for sharing the costs of expensive therapies for rare diseases. It has provided ERT to many patients with Fabry disease for several years. However, it was poorly designed to meet its outcome goals and has been unable to provide therapy to all individuals with the disease. Therefore, many stakeholders saw this initiative as an inappropriate solution.

Conclusions: The CFDI has not met the expectations of key informant groups and some modifications may be necessary. A registry study might better accomplish the CFDI's original goals of providing access to treatment, gathering data and monitoring patients' progress.

Introduction

Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder that affects patients of both sexes. The effects of this disease are multisystemic and progressive. Symptoms usually begin in childhood and patients may experience periodic episodes of severe pain in the extremities (acroparesthesias), vascular cutaneous lesions (angiokeratomas) and corneal and lenticular opacities, among other symptoms.1 Worsening of renal function to end-stage renal disease often occurs in men in the third to fifth decade of life and many of these patients experience cardiovascular and/or cerebrovascular disease or stroke.2

Key points.

Most developed countries have an orphan drug policy that facilitates access to and reduces the costs of expensive drugs for rare diseases, but Canada does not. Drug reimbursement is a provincial or territorial jurisdiction.

Expensive drugs for rare diseases are almost always not recommended for reimbursement by the Common Drug Review because of lack of demonstrated cost-effectiveness. As a result, provinces typically decide against funding the treatments.

The Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI) was created as a potential model for sharing the costs of and increasing access to expensive drugs for rare diseases.

Results from this study may be helpful for the design of future real-world drug trials and for the design of a national reimbursement program for orphan drugs.

The information in this study can be used by pharmacists and others to defend the position that an orphan drug policy is needed in Canada, to allow patients better access to expensive drugs for rare diseases, with recognition of the financial challenges that these drugs typically entail.

Points clés.

La plupart des pays développés se sont dotés d'une politique sur les médicaments orphelins qui facilitent l'accès à des médicaments onéreux utilisés pour le traitement des maladies rares tout en réduisant les coûts. Le Canada n'en fait pas partie. Le remboursement des médicaments est un domaine de compétence provinciale ou territoriale.

Les médicaments onéreux utilisés pour le traitement des maladies rares font peu souvent l'objet d'une recommandation dans le cadre du Programme commun d'évaluation des médicaments parce qu'on n'a pas réussi à établir leur rentabilité. Par conséquent, les provinces refusent habituellement de financer les traitements.

L'Initiative canadienne de recherche sur la maladie de Fabry a été élaborée comme modèle de partage des coûts et pour favoriser l'accessibilité aux médicaments onéreux utilisés pour traiter des maladies rares.

Cette étude sera utile pour la conception future des essais de médicaments dans le monde réel et lorsque viendra le temps d'élaborer un programme national de remboursement des médicaments orphelins.

Les pharmaciens, entre autres, pourront utiliser les renseignements publiés dans cette étude pour défendre le fait qu'une politique sur les médicaments orphelins est nécessaire au Canada et pour permettre aux patients d'avoir un meilleur accès aux médicaments onéreux utilisés pour traiter les maladies rares tout en reconnaissant les difficultés financières associées habituellement à ce genre de médicaments.

In 2000, 2 enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) drugs, agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme) and agalsidase alfa (Replagal), became available to treat Fabry disease. Both drugs are approved for use in Canada on the basis of safety and effectiveness data. Patients gained access to the treatments either by volunteering for clinical trials or through Health Canada on compassionate basis (free of charge). However, in 2005, the Common Drug Review (CDR) recommended against coverage of the 2 drugs by public drug plans, because of a lack of cost-effectiveness (with each drug costing about $300,000 per year), limited meaningful clinical outcomes and a lack of evidence of improvements in quality of life.3 Following this decision, the manufacturers stopped providing treatment on a compassionate basis and patient outrage ensued.4,5 Most patients in British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario continued to receive treatment through separate provincial agreements with the pharmaceutical companies. However, the other provincial governments did not develop these agreements or design programs and thus patients stopped receiving care. Of particular concern was Nova Scotia, where a large proportion of patients with Fabry disease reside. These patients stopped receiving ERT because the provincial government decided not to offer coverage and no arrangement was made with the manufacturers.

By late 2005, in response to increasing demands from physicians and their patients with Fabry disease for access to ERT, the federal and provincial governments undertook a nationwide clinical research study called the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI; clinical trial registration NCT 004551046). The CFDI, which was continuing to recruit patients at the time of the current study, has 3 main objectives: collection of longitudinal data on the effectiveness of ERT, comparison of the 2 available treatments when given at manufacturers' recommended doses and observation of progression of Fabry-related symptoms in patients who do not meet inclusion criteria for the CFDI.7 Patients who enroll as participants in this longitudinal study and who meet the inclusion criteria are randomly assigned to receive one of the 2 ERT treatments. Patients who do not meet the inclusion criteria8 are enrolled in a natural history cohort, which is being used to study progression of the disease.

In terms of its protocol, the CFDI is similar to many other clinical trials; however, 2 characteristics distinguish it from a typical clinical trial or a “coverage with evidence development” research trial. Although the CFDI has outcome objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, assignment to groups and specified data collection methods6 (like most other clinical trials), it also has a unique funding arrangement and a distinctive purpose. The funding arrangement, the first of its kind, specified a 3-year cost-sharing arrangement between the federal and provincial governments and the manufacturers.4 Details of the cost-sharing relationship have not been made public. In terms of its purpose, the CFDI was developed with the potential to serve as a model for funding for access to and study of the real-world use of expensive drugs for rare diseases in Canada.4

To date, the CFDI has not been evaluated. A qualitative approach to evaluation can generate a rich description of the intervention that is being evaluated, resulting in an inclusive depiction of the intervention's usefulness from a variety of perspectives.9 The goal of the present study was to provide useful and meaningful information about the CFDI to decision-makers and other key stakeholders.

Methods

The Dalhousie University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board approved the study. The study was designed to evaluate the CFDI from a key informant perspective using a qualitative methods strategy involving semistructured interviews, a holistic-inductive design and content analysis. “Key informants” should be individuals with special knowledge of a program (in this case, the CFDI) who are willing to share their knowledge through a means that is not available elsewhere.10 For this study, key informants were defined as individuals with firsthand knowledge of the CFDI, through experience as patients, involvement in the infrastructure of the program (CFDI investigators), experience with the policies pertinent to the CFDI (government officials) or involvement in provision of one of the drugs (manufacturers). These groups were chosen because of their experience with and active role in the CFDI. Patients were identified through membership in the Canadian Fabry Association. CFDI investigators were identified through contact information for each local study site. Government representatives were contacted by e-mail through government websites. Pharmaceutical manufacturers were reached through contact information published on their respective websites. Each person who agreed to participate was interviewed by telephone or in writing. Participants were prompted with questions from an interview guide (developed in advance to explore all aspects of the CFDI) and were asked additional questions that emerged during the interview. A copy of the interview guide can be obtained from the lead author upon request.

The study used qualitative content analysis methods to evaluate the CFDI. This approach is supported by Patton11 and Greene12 as an effective and informative design for evaluation that provides a holistic perspective of the program. More specifically, qualitative content analysis was used both within and between key informant groups.6,13 ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; www.atlasti.com) was used for identification of codes and code families and for data reduction.

For both within- and between-group analyses, the data were compared, reviewed and indexed on an ongoing basis, with analyses being performed while the investigators were transcribing the interviews, taking notes, reading and rereading the transcripts and reducing the data. The choice of an organizing style is the first step to the analysis. Crabtree and Miller14 suggest choosing from 3 styles: template style, editing style and immersion/crystallization style. These 3 options serve as starting points for analyzing the data and are not necessarily mutually exclusive. This evaluation predominantly used the editing style. This method is useful when little information is available before data collection, and the researcher chooses to develop codes during the analysis phase rather than preselecting expected codes. In this case, while information is available about the CFDI research outcomes and protocol, little is known about individual perspectives of the CFDI from its investigators, patients, government representatives and treatment manufacturers.

Applying specific characteristics of the other styles is often a good practice and was used in the evaluation.14 The editing style was complemented by using some components of the template and immersion/crystallization styles. Similar to the template style, research questions were formed prior to the analysis, which was used as a lens for beginning analysis, but no coding manual was predetermined to categorize emerging codes. In a process characteristic of the immersion/crystallization style,14 the researcher spent an extensive amount of time reading and rereading the transcripts, listening to the interviews and reviewing analytic notes and memos.

Employing the editing style process, the researcher entered the analysis phase without any predetermined codes. Codes (labels used to identify responses from participants) were identified within the data and were used to establish interconnectivity between participants' responses.15 Codes were created while the researcher was immersed in the data and information deemed important was extracted then attributed the label.14 For example, codes were used for data representing specific ideas, perspectives, opinions and experiences that were identified through the interview and subsequent data analysis. This recognition of interconnectivity was then followed by data reduction.16

More specifically, data reduction occurred through the process of identifying important information, giving it a code, and then when similar information was provided by the same or a different participant, the relevant code was applied to that information. Whenever a new code emerged from the data, previous transcripts were reread for information relevant to that code. This process ensured that different codes were not used to represent the same information. The final set of codes was then indexed and further refined, on the basis of similarities, to construct categories of codes.10 These code categories were further investigated and linked to uncover commonalities that helped in developing themes about the CFDI.10,11,17 The themes consisted of ideas and concepts emerging from the categorized data. Themes exist throughout the corpus, and represent patterns of textual information that are prominent throughout the collected data, and were used to generate conclusions about the CFDI. This process was repeated with new interviews that provided novel information until no new information emerged from the texts (as suggested by Pope et al.13).

The between-group analysis was conducted to find themes “that cut across cases”12 and to identify key patterns from all groups that would indicate the overall effectiveness of the CFDI from the perspectives of the various stakeholders. A second individual was used through the entire analysis to code all the data from both within and between group analysis to ensure quality and credibility of the analysis.

Results

The investigators attempted extensive recruitment from each of the key informant groups, however, many potential participants either declined or were too difficult to contact. Overall, 17 semistructured interviews were conducted by telephone in May and June 2009: 4 with patients; 8 with CFDI investigators, nurses and coordinators; 2 with provincial government representatives; and 3 with representatives of the pharmaceutical industry. One potential respondent of the patient group was unavailable for a telephone interview and this person completed a written questionnaire consisting of the interview questions. There was a total of 18 study participants. According to qualitative research standards, this is an acceptable sample size for a qualitative study with small groups of key informants.18 Interviews were deemed to be complete when the interviewee had responded to all questions deemed relevant to the evaluation. Recruitment of additional participants for the patient and government groups was attempted but was unsuccessful, because of difficulty contacting potential participants, lack of availability and self-exclusion due to lack of insight into the CFDI. Nonetheless, data saturation was achieved for the available participants.13

A total of 78 codes were identified during the analysis. Inter-rater reliability for 2 transcripts was 83%, which has been deemed satisfactory.19 The primary investigator (ME) used qualitative content analysis and data reduction to classify the codes into 23 categories and then to identify 13 themes from further study of the categories. The 10 within-group themes were CFDI challenges, positive characteristics of the CFDI, negative characteristics of the CFDI, model of orphan drug policy, patient concerns, primary objective of the CFDI, origin of the CFDI, government challenges, lessons learned and patient objectives. The 4 between-group themes were importance of the CFDI, CFDI protocol in stasis, use of research to solve a reimbursement problem and alternative policies. The within-group and between-group results were analyzed separately.

Themes from patients

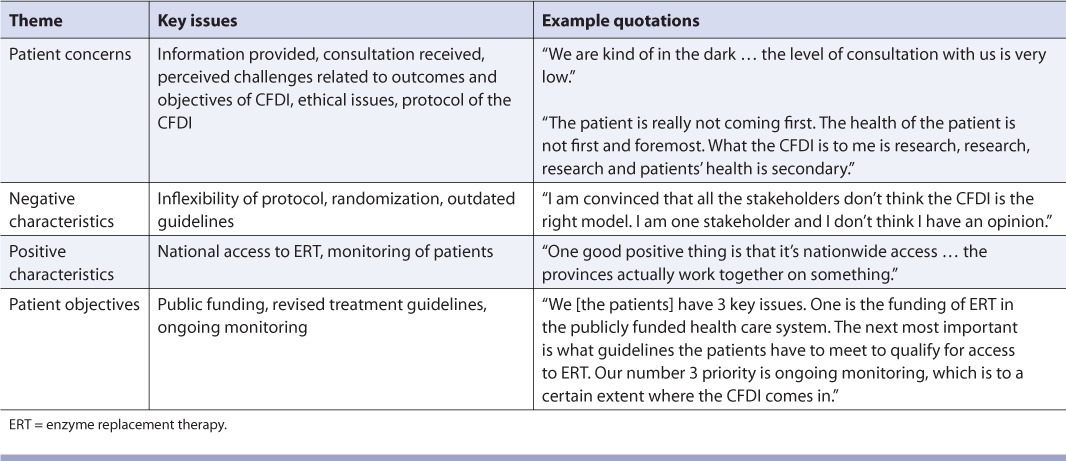

Four dominant themes emerged from the interviews with patients with Fabry disease (Table 1). Overall, the patients were pleased that they had access to ERT; however, they were concerned that their access to treatment was linked to participation in a research trial. Patients felt that they were not well informed about perceived challenges related to the outcomes and objectives of the CFDI, ethical issues and the CFDI protocol. Patients reported that if they had received more information and consultation, they wouldn't have felt “in the dark.” They also thought that each patient should have had more influence in choosing his or her treatment.

TABLE 1.

Evaluation of the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI): Themes from patients

Themes from CFDI investigators

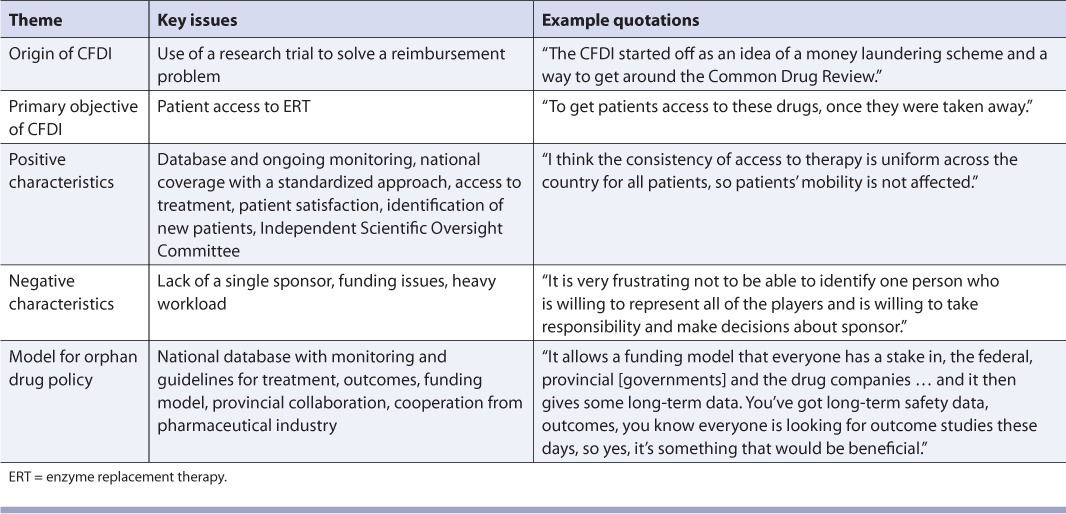

Five themes emerged from the interviews with the CFDI investigators (Table 2). Overall, the investigators described the initiative as a well-organized, centralized program headed by specialized physicians who provide access to ERT and who monitor and record the progress of patients receiving treatment.

TABLE 2.

Evaluation of the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI): Themes from Investigators

Themes from provincial government representatives

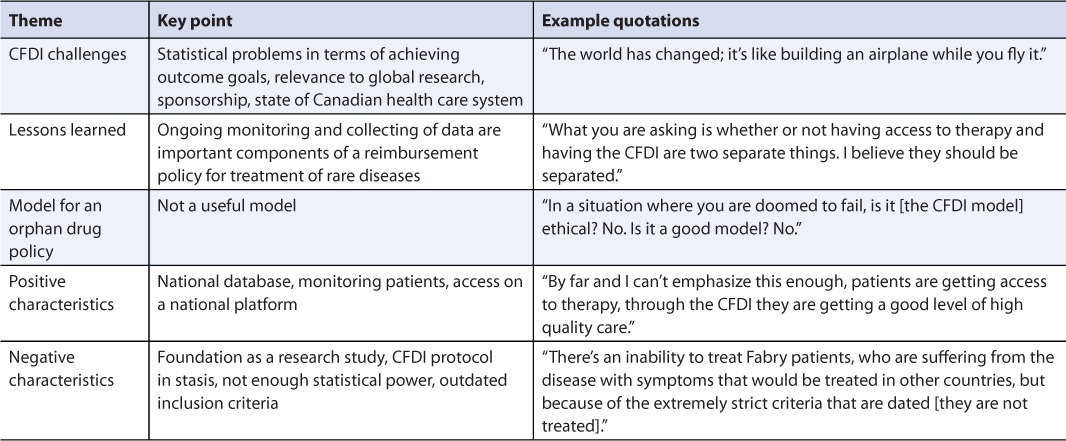

Four themes were identified by analysis of responses from provincial government officials (Table 3). Overall, the provincial government representatives felt that linking research to access was problematic because it may not be feasible to conduct a research study within a public drug program. However, they suggested that the CFDI was successful because it provided access to ERT while allowing researchers to gather more information about the effectiveness of the therapy.

TABLE 3.

Evaluation of the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI): Themes from provincial government representatives

Themes from pharmaceutical manufacturers

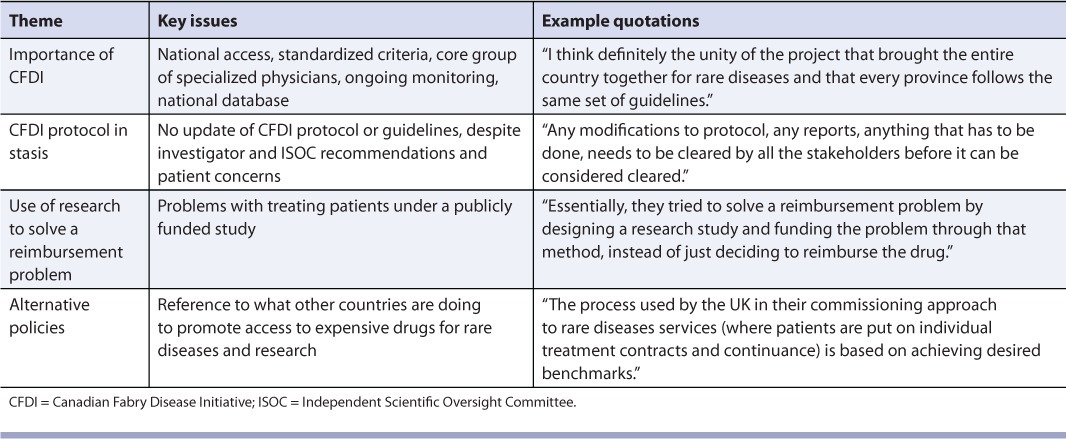

Five themes emerged from the interviews with the pharmaceutical manufacturers (Table 4). The companies were satisfied with the arrangements made when the CFDI was initiated; however, the inability to change the protocol or outcome measures of the CFDI as new information became available was seen as a major drawback.

TABLE 4.

Evaluation of the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI): Themes from pharmaceutical manufacturers

Themes that cut across groups

Four themes were identified in the responses of all groups (Table 5). Within the importance of the CFDI theme, positive features of the CFDI included national access to treatment on the basis of standardized criteria and administration of therapy by a core group of specialized physicians who conducted ongoing monitoring within a national database. Conversely, one problem identified by all groups was that the CFDI had not updated its protocol or guidelines since initiation of the study, despite the recommendations of investigators and the Independent Scientific Oversight Committee and concerns expressed by patients. In particular, treatment cannot be initiated for patients who were ineligible for treatment at the outset (and who were therefore assigned to the natural history cohort) but whose symptoms have become more severe over time. In addition to problems related to changing the CFDI protocol, some respondents had philosophical problems with treating patients in the context of a publicly funded clinical trial. As one participant stated, “Essentially, they tried to solve a reimbursement problem by designing a research study and funding the problem through that method, instead of just deciding to reimburse the drug.” Participants wanted the federal government to take the lead and “kick-start issues around making changes to help Canada's policy of reviewing and approving a drug for rare disorders.”

TABLE 5.

Evaluation of the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative: Themes cutting across all groups

Discussion

Several revealing themes emerged from analysis of key informants' comments about the CFDI, including the idea that the CFDI was essentially a research study designed to solve a reimbursement problem in Canada. Respondents noted that rather than acknowledging and addressing potential weaknesses in the CDR process for expensive drugs for rare diseases, the federal and provincial governments set up a clinical trial to provide access to ERT for some patients and to allow collection of data on both patients and treatments. However, the study did not have enough funding to accomplish its clinical outcome goals and its rigid inclusion criteria for treatment restricted access to ERT. A major concern was that the CFDI did not have sufficient leadership to update its protocol, even though it was recommended by investigators, which left key informants unsatisfied that not enough patients were receiving ERT.

Another problem with this approach was the lack of a lead sponsor or administrative body that could implement modifications to the protocol. Therefore, not only was the CFDI unable to accomplish its (unofficial4) primary objective (to provide long-term access to ERT for patients with Fabry disease) but it was also unable to adjust to adversity or implement policy recommendations made by the investigators. This inability to change treatment guidelines in response to emerging evidence was perceived by participants in the current study as a major weakness of the CFDI. As one participant pointed out, “It is like building an airplane while you fly it.”

Despite its faults, the CFDI has provided ERT to many Canadian patients with Fabry disease on a nationally standardized basis, in the absence of any alternative for provision of this therapy, with patients receiving a high standard of care from specialized physicians. The study has also allowed monitoring and documentation of the progression of Fabry disease and the effectiveness of 2 forms of ERT. As one key informant indicated, the CFDI “brought the country together on rare diseases.” In addition, the CFDI has provided hope for future interprovincial collaborations and has demonstrated that patients with rare diseases can be treated with expensive drugs for these diseases and monitored on a national basis. The CFDI also provides an access point through which pharmacists can refer any patient with Fabry disease who does not already know about the study.

In retrospect and for similar future initiatives, a registry study might have been more appropriate. For example, a large US registry sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, which is enrolling patients with Fabry disease,20 has outcome goals similar to those of the CFDI. Registries such as the Canadian Cancer Registry, the Gaucher Registry, the Canadian Haemophilia Registry and the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Disease Registry are examples of effective models for gathering data and enrolling a greater proportion of affected patients for treatment without the stringent guidelines of a clinical trial. For example, the Canadian Cancer Registry is a collaborative effort that first collects information from all provincial registries and then compiles the data centrally to better describe various forms of cancer and their treatments. In particular, the Canadian Cancer Registry has generated high-quality data on the progression of many forms of cancer since 1968,21 and many studies using its data have been published.22 The number of patients in the natural cohort arm of the CFDI may not be as large as the numbers of patients in these registries, but using a registry approach might give more patients access to treatment because of the less restrictive treatment guidelines associated with a registry. Patients, with the advice of their respective physicians, would also be given a choice of treatment. A comprehensive comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of a registry study and a clinical trial would be needed to better determine the potential overall advantages of a registry study; nonetheless, the results of the current study indicate that the value of a registry study is worthy of further investigation.

A hybrid of current registry systems, based on the recommendations of Clarke,23 may be the most appropriate solution to funding for expensive drugs for rare diseases in Canada. Clarke's proposal for a national drug program for expensive drugs for rare diseases includes a commitment, primarily funded by industry, to ongoing monitoring of patients receiving the treatment through a registry study. If this strategy were to be applied to Fabry disease, the CFDI funding arrangement would be modified slightly, with potentially less dependence on federal contributions. This approach could remedy many of the perceived negative characteristics of the CFDI, such as design inflexibility, accessibility, treatment choice, stasis problems and leadership issues. It would also keep many of the strengths, such as national coverage, collaboration, data collection and patient monitoring.

Clarke's proposal also specifies that physician reporting to the registry would be a requirement for patient access to therapy. Furthermore, the registry would be maintained by a rare disease expert committee comprising internal and external reviewers from a variety of health disciplines. The lead investigators of the CFDI form a similar body that could fulfill this role. The data gathered from the registry may help in making better post-evaluation decisions. Establishing such a registry could provide benefits similar to those of the CFDI, such as providing access to therapy for patients, monitoring and funding, while removing the strict requirements of a clinical trial protocol, such as randomization of treatment and static guidelines. A national strategy for Fabry disease based on Clarke's recommendations could use the current infrastructure of the CFDI as the registry and the existing CDR as a method of evaluation.

Before new policies concerning access to expensive drugs for rare diseases are developed, the authors of the current study contend that the federal and provincial governments should review what is being done internationally. More specifically, international policies could be investigated to compare desired and actual outcomes and successful policies could then be evaluated to determine whether similar policies could be implemented in Canada.

The limitations of the current study include the low number of government decision-makers who agreed to participate (2 provincial government representatives and no federal government representatives). When contacted, the federal government referred the original request to participate to a province that did not participate in the CFDI (and therefore did not qualify for inclusion in the study). The Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the CFDI's Independent Scientific Oversight Committee (ISOC) were pursued because funding for the CFDI goes through the CIHR, and the ISOC was developed to evaluate the program. However, both declined to participate, citing a conflict of interest. Inclusion of these missing groups would have enhanced our evaluation of the program.

Notably, the original 3-year funding arrangement for the CFDI ended on September 30, 2009. According to the Canadian Fabry Association (personal communication, Canadian Fabry Association, October 13, 2010), funding has been extended to September 30, 2012. However, the funding arrangements have changed, with the cost-sharing arrangement now involving only the provincial governments and the pharmaceutical manufacturers; the federal government is no longer involved.

Conclusions

Some aspects of the CFDI could be used to develop a model of cost-sharing and drug access in Canada for expensive drugs for rare diseases. For example, the CFDI demonstrated that provinces can collaborate in providing access to an expensive drug for a rare disease to a qualified sample of patients. This approach could function as a foundation for a national orphan drug reimbursement program. However, a contentious aspect of the CFDI is that it links reimbursement to research, which raises many ethical issues that should be further investigated before similar initiatives are developed. Furthermore, from a clinical trial perspective, the CFDI was not well designed to meet its outcome goals and from an access perspective, it has not been flexible or well organized enough to meet the expectations of many stakeholders.

The findings of this qualitative evaluation study also have direct application to practising physicians and pharmacists. For example, this study may help to facilitate conversations about drug coverage for rare diseases and the associated challenges for patients, for federal, provincial and territorial governments and for the pharmaceutical industry. The major stakeholders in drug reimbursement decisions all have strongly vested interests and it is typically front-line health professionals, such as community pharmacists, who end up explaining policy decisions to patients.24 In addition to national drug reimbursement programs, such as the CFDI, provincial programs exist to reimburse drug costs for some individuals with specific rare diseases. Increasingly, pharmacists are acting as patient navigators, helping patients to sort through the myriad drug reimbursement programs available from both public and private payers. This responsibility becomes increasingly challenging with initiatives such as the CFDI, because front-line pharmacists are not directly integrated into the program design or administration. Therefore, patient-oriented pharmacists may not be able to provide their patients' appropriate information about the CFDI and their options.

Although pharmacist perspectives were not incorporated into this qualitative program evaluation, their expertise and experience could provide a source for future evaluations into national drug programs such as the CFDI. Pharmacists' insight could provide an alternative method to provide expensive drugs for rare diseases to patients and should be pursued.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable contributions of Dr. James Brophy, Dr. Andrew Orr, Dr. Daryl Pullman, Dr. Tom Rathwell, Andrea Scobie, Dr. Ann Thompson and Dr. Michael West.

References

- 1.Ramaswami U. Update on role of agalsidase alfa in management of Fabry disease. Drug Design Devel Ther. 2011;12:155–73. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S11985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfadhel M, Sirrs S. Enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease: some answers but more questions. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;23:69–82. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S11987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment. 2005. CEDAX final recommendation and reasons for recommendation: agalsidase beta resubmission. Available: www.cadth.ca/media/cdr/complete/cdr_complete_Fabrazyme_Resubmission_may2005.pdf (accessed Oct. 12, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bichet D, Casey R, Clarke J, et al. 2008. Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative annual report October 1, 2006 – November 30, 2007. Available: www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/36618.html (accessed Oct. 12, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. 2010. Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative study: scientific oversight. Available: www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/35799.html (accessed Oct. 12, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 6.ClinicalTrials.gov. Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative (CFDI) enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) study. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00455104 (accessed Nov. 28, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sirrs S, Clarke JTR, Bichet DG, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke LA, Clarke JTR, Sirrs S, et al. Fabry disease: recommendations for diagnosis, management and enzyme replacement therapy in Canada. Garrod Association. Available: www.garrod.ca/data/060613-1322-01.html (accessed Oct. 12, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1101–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilchrist VJ, Wlliams RL. Key informant interviews. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 71–88. p. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene J. Qualitative program evaluation. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. London (UK): Sage; 1994. pp. 530–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. The dance of interpretation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. Second edition. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications, Inc.; 1999. pp. 127–43. p. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen G. A critique of using grounded theory as a research method. Electron J Bus. Res Methods. 2003;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huberman A, Miles M. Data management and analysis methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. London (UK): Sage; 1994. pp. 428–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bereska T. The changing boys' world in the 20th century: reality and “fiction.”. J Mens Stud. 2003;11:157–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Politz D, Beck C. Nursing research principles and methods. 7th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Côté AM, Durand MJ, Tousignant M, Poitras S. Physiotherapists and the use of low back pain guidelines: a qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:94–105. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopkin R, Bissler J, Banikazemi M, et al. Characterization of Fabry disease in 352 pediatric patients in the Fabry Registry. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:550–5. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318183f132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Band PR. The making of the Canadian Cancer Registry: cancer incidence in Canada and its regions, 1969 to 1988. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Council of Cancer Registries, Health and Welfare Canada, Statistics Canada; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellison LF. An empirical evaluation of period survival analysis using data from the Canadian Cancer Registry. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke J. Is the current approach to reviewing new drugs condemning the victims of rare diseases to death? A call for a national orphan drug review policy. CMAJ. 2006;174:189–90. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacKinnon NJ. Provincial drug plans: now there's a minefield. Can Pharm J. 2004;137:14–6. [Google Scholar]