Abstract

Background: While pharmacists are trained in the selection and management of prescription medicines, traditionally their role in prescribing has been limited. In the past 5 years, many provinces have expanded the pharmacy scope of practice. However, there has been no previous systematic investigation and comparison of these policies.

Methods: We performed a comprehensive policy review and comparison of pharmacist prescribing policies in Canadian provinces in August 2010. Our review focused on documents, regulations and interviews with officials from the relevant government and professional bodies. We focused on policies that allowed community pharmacists to independently continue, adapt (modify) and initiate prescriptions.

Results: Pharmacists could independently prescribe in 7 of 10 provinces, including continuing existing prescriptions (7 provinces), adapting existing prescriptions (4 provinces) and initiating new prescriptions (3 provinces). However, there was significant heterogeneity between provinces in the rules governing each function.

Conclusions: The legislated ability of pharmacists to independently prescribe in a community setting has substantially increased in Canada over the past 5 years and looks poised to expand further in the near future. Moving forward, these programs must be evaluated and compared on issues such as patient outcomes and safety, professional development, human resources and reimbursement.

Introduction

Pharmacists are highly trained in the appropriate selection and management of prescription medicines. Traditionally, outside hospitals and team-based primary care centres, pharmacists have seldom been called upon to take a lead role in decisions around the initiation of medicines requiring a prescription. However, within the last 5 years, a number of provinces have revisited the role of pharmacists and introduced policies that expanded the pharmacy scope of practice.1 These policies have included the ability to independently initiate, adapt (modify) and continue prescriptions.

Key points.

Many provinces have expanded the scope of pharmacist practice to include renewing, adapting and initiating prescription drugs.

There are major differences in the scope permitted between different provinces.

In the future, these changes should be evaluated for their impact on drug use, costs and health outcomes.

Points clés.

De nombreuses provinces ont élargi le champ d'exercice des pharmaciens pour y inclure le renouvellement et l'ajustement d'une ordonnance, ainsi que l'instauration d'une pharmacothérapie sur ordonnance.

Il existe toutefois de grandes différences entre les provinces quant au champ d'exercice autorisé.

Il y aurait lieu à l'avenir d'évaluer ces changements afin d'en déterminer l'incidence sur l'usage et les coûts des médicaments de même que sur les résultats pour la santé.

These policies may impact access to medicines, the quality of prescribing and patient monitoring. Canadians spent approximately $25 billion on prescription drugs in 2009, over half of which was spent on long-term-use drugs such as those to manage cardiovascular risk factors and disease.2,3 However, both prescribing and medication adherence can be suboptimal. Medication adherence is particularly a challenge for chronic conditions.4,5 As most provinces limit prescription length to 3 months and 4 million Canadians report not having a regular physician, access to primary care doctors for the purpose of prescription renewal may be a barrier to optimal medication use.6 Thus, granting pharmacists prescribing authority may help to improve medication adherence by making refills and emergency supplies more readily available to these patients. For example, pharmacists may offer care when other providers are closed or may be more geographically accessible for some individuals. Further, policies that give pharmacists a greater role in prescribing and managing medication use may improve treatment quality by improving drug selection, dosing, use and monitoring.7–11

Numerous Canadian provinces have implemented programs designed to expand the scope of pharmacists' practice. These programs have been established in the hopes that they will improve access and adherence to medicines, reduce ambulatory physician visits and improve patient outcomes. However, the rules and regulations vary substantially among provinces and have been the subject of considerable controversy.12 In this paper, we provide a summary of these independent prescribing rights across Canada as they existed in August 2010. We also note other provinces where legislation or regulations that will expand pharmacists' scope of practice are in development.

Methods

Between May and August 2010, we conducted a comprehensive policy review and comparison of documents and regulations from the relevant government and professional bodies. To clarify uncertainties and the current state of policy development, we spoke with contacts in every provincial pharmacy regulatory body (colleges and boards). We also offered informants in every province the ability to comment on an earlier version of this manuscript in January 2011. We did not include policies that only apply to one particular type of drug, such as the prescribing of emergency contraception or blood products. Further, we focused on independent prescribing policies that generally apply to the prescription of drugs in community pharmacy practice and not to “delegated authority” provisions found in several provinces or the ability of pharmacists to administer injections (such as vaccines).13

We analyzed the independent prescribing rights afforded to pharmacists in each province in terms of 1) continuing existing prescriptions, 2) adapting existing prescriptions and 3) initiating new prescriptions. Within each function, we sought information on what requirements pharmacists had to fulfill (including training and liability insurance), whether there were continuing education requirements, what rules applied to the practice (such as limitations on particular drugs) and whether reimbursement was provided for the services.

Results

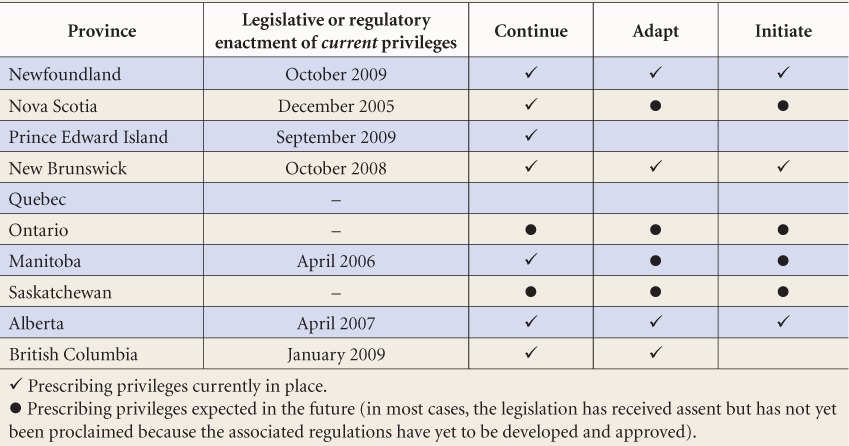

As shown in Table 1, our review found that pharmacists can independently prescribe in nearly every province. Below, we discuss some of the specific rights of pharmacists in each province.

TABLE 1.

Major characteristics of pharmacist prescribing rights in Canadian provinces as of August 2010

Continuing prescriptions

Pharmacists in a number of provinces have the ability to independently continue or renew prescriptions under a range of rules. These policies have 3 typical forms: 1) allowing pharmacists to renew prescriptions for long-term conditions, 2) permitting short-term dispensing to allow patients to continue therapies uninterrupted and 3) allowing pharmacists to prescribe in emergency situations.

Alberta

In Alberta, pharmacists on the clinical registry of the Alberta College of Pharmacists (ACP) are permitted to renew prescriptions as outlined in the Health Professions Act Standards for Pharmacist Practice (2007).14 An orientation program for existing pharmacists was delivered by the ACP and could be completed as a home study program15 or at an orientation session. In 2009, all pharmacists were required to complete the orientation program to renew their practice license.

All renewals must be reported to the original prescriber. If the pharmacist does not have the original prescription but the patient has provided evidence of ongoing therapy and is in immediate need of drug therapy, short-term renewals are allowed to ensure continuity of care. Prescriptions must be of the minimum length necessary to give the patient the opportunity to visit the original pharmacy or prescriber and cannot be for a controlled substances.* Following the introduction of prescribing privileges, pharmacists in Alberta must hold a minimum of $2 million professional liability insurance. Further, to prescribe, they must assess the patient and assume full responsibility for their prescribing decisions.

British Columbia

Pharmacists in British Columbia can renew prescriptions after completing an orientation process that is outlined in the Professional Practice Policy 58 (PPP-58).17 Renewals are permitted for patients with stable, chronic conditions who have been on the same medication with no changes for at least 6 months. Pharmacists can only renew prescriptions up to 6 months after the original prescription. Pharmacists were reimbursed $8.60 for performing a renewal, which was equal to the dispensing fee, when the policy was introduced. Renewals for controlled substances are not permitted and community pharmacists are not permitted to renew psychiatric medications. To exercise prescribing privileges, pharmacists must hold a minimum of $2 million personal professional liability insurance and must adhere to a series of professional guidelines outlined in the PPP-58 Orientation Guide.17

Manitoba

A 2006 joint agreement between the Manitoba Pharmaceutical Association, College of Physicians and Surgeons and College of Registered Nurses allows pharmacists to prescribe continued care prescriptions if they are unable to contact the original prescriber.18 The prescription must be for a long-term or chronic condition for which the patient has an established stable history on the medicine and the original prescription must have been filled at the same pharmacy. Narcotics and controlled substances cannot be provided under this agreement and benzodiazepines can only be prescribed for the management of convulsive disorders or if there is a risk of seizure. The amount of medication dispensed cannot exceed the amount previously filled. These prescriptions must be reported to the original prescriber and primary care physician by the next business day.

New Brunswick

As of 2008, New Brunswick pharmacists can continue therapy for current patients or for new patients after assessing them and determining that their previous treatment is still valid.19 Furthermore, the Continued Care Prescriptions Policy of the same year allows pharmacists to provide a continued care prescription for benzodiazepines and targeted substances when the medication is being used to manage convulsive disorders or there is a risk of seizure due to withdrawal.20 New Brunswick requires notification to the original prescriber when the pharmacist deems the renewal “clinically significant.” Pharmacists are not remunerated for renewing prescriptions unless they charge the patient directly.

Nova Scotia

The Continued Care Prescriptions Agreement of 2006 allows pharmacists to provide a continued care prescription under certain circumstances for patients with an established stable history on a medication, not including narcotics or controlled substances.21 These prescriptions can only be made at the original pharmacy, can only be extended once and cannot exceed the shorter of either the length of the original prescription or 1 month. Pharmacists are obligated to report renewals to the original prescribing physician or primary care physician as soon as possible and to record their own name as the prescriber.

Prince Edward Island

Regulations in Prince Edward Island allow pharmacists to provide continued care prescriptions only if the pharmacy holds the original prescription. Under these regulations, the pharmacist can refill a prescription if there is an immediate need to continue the treatment and it is not reasonable for the patient to obtain a new prescription before the original expires or the last refill is finished.22 Continuing care prescriptions cannot exceed the amount authorized per refill under the original prescription, cannot be refilled and pharmacists cannot provide consecutive refills for the same drug to the same patient. The pharmacist must hold a minimum of $2 million liability coverage and adhere to accepted standards of practice. Pharmacists cannot provide continued care prescriptions for controlled drugs or benzodiazepines unless the original prescription was to manage convulsive disorders or there is a risk of seizure. Pharmacists must inform the original prescriber in writing as soon as possible and pharmacists are to record their own name as the prescriber on the drug container label and in the patient record.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Under the scope of medication management, pharmacists in Newfoundland and Labrador can also extend a prescription.23 Pharmacists may only extend prescriptions for a chronic or long-term condition when the patient has an established stable history on the medication in question and it is not possible for the individual to visit the prescriber “in a timely manner.” The refill cannot exceed the lesser of the amount previously filled or 90 days worth of medication. After continuing the prescription, the pharmacist must document the details in the patient medication profile, record his/her own name as the prescriber and notify the original prescriber within 1 week. Continuing care prescribing is only allowed if the original prescription was filled at the pharmacy in question.

Adapting prescriptions

When we conducted our review, Canadian pharmacists in 4 provinces could independently adapt prescriptions. Modifications entail changes to an existing prescription with respect to the dose, formulation, instructions for use and choice of specific agent within a therapeutic area.

Alberta

The 2007 rules that introduced prescription renewal in Alberta also introduced independent prescription adaptation by pharmacists.14 As for prescription renewal, pharmacists on the ACP clinical registry can modify the dose, formulation or regimen of a prescription and make therapeutic substitutions. The adapting pharmacist must be in possession of the current and complete original prescription. Dosage alterations can only be performed on new prescriptions and pharmacists are limited to reasons including weight, age and organ function to justify the changes (e.g., not adverse effects). The pharmacist must notify the original prescriber and provide information on the type and amount of drug prescribed, the rationale for prescribing the drug, the date and the instructions given to the patient about the prescription. Adaptations are not permitted on prescriptions for controlled substances.

British Columbia

The regulations regarding pharmacist-initiated renewals in BC are detailed in PPP-58.17 In order to adapt prescriptions, pharmacists must complete and sign the orientation guide or attend a live educational session.17,24 BC permits pharmacists to change the dose, formulation or route of administration and to make within-class therapeutic substitutions for specified drug classes.17,24 In community settings, the regulations limit therapeutic substitutions to the same classes in which BC uses reference-based pricing: H2-blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, nitrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Further, pharmacists cannot modify the dose or regimen for prescriptions treating cancer, cardiovascular disease, asthma, seizures or psychiatric conditions. The prescription must be current and not have handwritten directions from the physician stating “do not adapt” (pre-printed or computer-generated instructions are not valid). The adapting pharmacist must notify the original prescriber within 24 hours. Pharmacists received $8.60 for adaptations and $17.20 for therapeutic substitutions, to a maximum of 2 clinical service fees per drug per patient every 6 months.

New Brunswick

In 2008, pharmacists in New Brunswick gained the authority to independently adapt prescriptions.19 Pharmacists can alter dose, formulation or regimen and make therapeutic substitutions. The pharmacist must have the original prescription and document the adaptation. As with renewals, notification is only necessary in cases where the pharmacist believes the adaptation is “clinically significant” based on his or her own judgment. No reimbursement is provided.

Newfoundland and Labrador

In Newfoundland and Labrador, pharmacists can change the dosage form, regimen or quantity of medication and substitute a brand name drug with a generic version not listed on the provincial formulary. They can also complete missing information on a prescription where there is historical evidence to support it (e.g., a missing dosage size on a long-standing prescription). Changes can be justified based on the potential for better adherence, private insurance reimbursement or availability of the drug. When adapting a new prescription, the pharmacist must document the adaptation on the prescription and notify the original prescriber within one week. Pharmacists cannot adapt prescriptions for narcotics or benzodiazepines or prescriptions for themselves or family members. Physicians can also prevent adaptation by writing “do not adapt” on prescriptions.

Initiating prescriptions

Alberta

In 2007, Alberta became the first province to allow pharmacists to independently initiate prescriptions.25 The province currently allows 2 forms of independent prescribing. The first type, emergency prescribing, allows all pharmacists on the clinical registry to prescribe the minimum quantity of the drug or blood product necessary to give the patient sufficient time to see a prescriber. In such cases, the pharmacist must provide the patient's regular physician with information on the drug prescribed and the instructions given to the patient.

Pharmacists may also apply to the ACP for additional prescribing authorization.26 The application process is outlined in the “Guide to Receiving Additional Prescribing Authorization.”26 Once granted the additional authority and trained in basic first aid and CPR, pharmacists can prescribe based on their own assessment of a patient. However, pharmacists who prescribe a drug based on their assessment of the patient cannot also be the dispensing pharmacist unless they have advised the patient that he/she may choose to have the prescription dispensed elsewhere. Pharmacists must establish a professional relationship with the patient and see the patient personally at the time of prescribing or have a collaborative relationship with another regulated health care professional who sees the patient in person. The pharmacist must document the rationale, assessment of the patient, prescription information, follow-up plan and the date and method of notification of other regulated health care professionals.

New Brunswick

New Brunswick allows pharmacists to prescribe emergency supplies of medicines for patients when the original prescriber cannot be contacted. All licensed pharmacists can prescribe and no additional liability coverage, beyond the current premium of $1 million, is required. Regulations in the province only mandate the notification of the primary physician when the prescribing decision is “clinically significant,” leaving it to the judgment of the pharmacist.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Similarly, pharmacists in Newfoundland and Labrador also have the ability to prescribe emergency supplies of medicines. The pharmacist must have acceptable evidence to support current ongoing drug therapy and can provide an interim supply of medication even if the original prescription was filled elsewhere. In this case, the pharmacist must only supply the minimum quantity required for the patient to visit the prescriber or usual pharmacy and must notify the original prescriber within 72 hours.

Future changes to prescribing authority

Saskatchewan

The regulations extending Saskatchewan pharmacists' authority to prescribe have been approved. Further, the bylaws of the Saskatchewan College of Pharmacists (SCP), which will govern the conditions around prescribing, were passed by the SCP College Council and approved by the Minister of Health. The bylaws came into force in March 2011.27 The bylaws for “Level 1” prescribing allow pharmacists to renew prescriptions, prescribe in emergency situations and adapt prescriptions, among other proposed privileges. 28 The bylaws also allow pharmacists to initiate prescriptions for minor ailments according to Council-approved evidence-based guidelines.

Manitoba

The Pharmaceutical Act (Bill 41), passed in 2006, gives pharmacists the right to prescribe and to order diagnostic tests. However, the pharmacy association membership in the province voted down draft regulations developed in March 2008. A new set of regulations was passed by the pharmacy association membership in November 2010.29 The new regulations authorize pharmacists to prescribe medicines for continuing care and to initiate prescriptions for steroids, antibiotics and antifungals for certain clinical indications.

Ontario

In 2009, Ontario passed ″Regulated Health Professionals Statute Law Amendment Act 2009″ (Bill 179) that allows pharmacists to both continue and modify prescriptions. Since our review in the summer, on March 7, 2011, the Council of the Ontario College of Pharmacists ratified a draft regulation to the Pharmacy Act to enable an expanded scope of practice that will include modifying and extending prescriptions and administering a substance by injection and inhalation for education and demonstration purposes.30 The draft regulation also allows pharmacists to initiate prescriptions for smoking cessation medicines. The proposed regulation has been submitted to government and is awaiting their approval.

Nova Scotia

In January 2010, the Nova Scotia cabinet passed regulations to the Pharmacy Act allowing independent prescribing by pharmacists. However, pharmacists waited until the Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists developed and approved the associated prescribing standards of practice in January 2011 to start using this authority.31 The standards allow pharmacists to exercise the prescribing authority authorized by the legislation and regulations, including the authority to renew existing prescriptions up to 90 days, to adapt the dosage, formulation, regimen or length of time a drug is to be taken and to perform within-class therapeutic substitutions. Pharmacists can also independently prescribe from a list of therapies to treat 31 minor and common ailments (e.g., dyspepsia, cough and nausea). The Continued Care Prescriptions Agreement discussed above also remains in effect.

Prince Edward Island

In 2008, the necessary legislation to enable pharmacist prescribing was passed by the PEI legislature (An Act to Amend the Pharmacy Act, Bill 10). The PEI Pharmacy Board has drafted a series of goals for regulations, the first of which involves prescribing in emergencies and adapting prescriptions by 2011.

Quebec

L'Ordre des pharmaciens du Québec has developed proposals that would allow pharmacists to independently extend and adapt prescriptions for specific patients and to prescribe independently for specific agents (e.g., smoking cessation therapies).32 As of August 2010, the proposals still needed to secure support from the government and physicians.

Discussion

As shown by our findings, substantial variation exists in the pharmacy scope of practice across provinces. We believe this variation results from having 10 separate provincial pharmacy regulatory bodies that vary in governance structure, legislation and standards and codes of conduct.1 Provinces will need to learn from each other as they determine the effectiveness of their regulation of prescribing privileges, including enforcement, remediation and sanctions. There is also a need for regulatory groups in pharmacists' professional bodies to work with other regulatory organizations (e.g., accreditation organizations). Our review suggests that researchers and policy-makers will need to consider various issues in planning the evaluation and future development of pharmacist prescribing in the community setting.

Knowledge, skills and continuous professional development

The existing provincial policies we reviewed varied in the type of formal and experiential education required by prescribing pharmacists. We found that while some provinces currently require additional training, certification or credentialing prior to receiving prescribing privileges, others require none. Provincial regulatory bodies also vary in their approach to continuing professional development. As the scope of pharmacy practice expands, all provinces will need to develop requirements for maintaining prescribing privileges, including tailoring continuing professional development requirements to the expanded scope of practice.

Reimbursement

We found that pharmacist reimbursement for prescribing practices varied across provinces. This may be because some provinces are allowing prescribing in order to enable other reimbursed services, such as medication management. Further work is needed to determine the cost-effectiveness of pharmacist prescribing. An expanded scope of practice may also provide an opportunity to transition pharmacy payment to a more cognitive service–based model.33 Safeguards are needed to manage potential economic conflicts of interest, as pharmacists and pharmacies can potentially benefit financially from the sale of the drugs they prescribe.34,35

Evaluation

To date, there has been limited research on the use of pharmacist prescribing in Canada and the impact on patient adherence to medications, patient health outcomes, health services use, patient acceptance and drug costs. Three-quarters of pharmacists in Alberta reported that they regularly wrote prescriptions 1 year after their policy change.25 In BC, 96,890 adaptations and renewals were performed over the first year of their policy, 80% of which were renewals.36 However, little other publicly available data exist with which to evaluate these programs. A number of evaluation activities are ongoing.37 Given the variation in policies across Canada at this early stage, translation of the findings will be critical as the prescribing privileges for pharmacists are refined in the future.

Conclusion

The legislated ability of pharmacists to independently prescribe in a community setting has increased substantially in Canada over the past 5 years, but varies widely across provinces. Independent prescribing appears poised to expand into other provinces in the near future. This makes it likely that every province will soon have pharmacists who are able to independently continue, adapt or initiate prescriptions in some form.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Neila Auld, Mary Ann Butt, Michel Caron, Dale Cooney, Cameron Egli, Ronald Guse, Ray Joubert, Marshall Moleschi, Gary Meek, Tina Perlman, Donald Rowe and Susan Wedlake for their valuable input and for their comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial acknowledgements: This research was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funders had no role in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the paper; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

*Controlled substances are those included in Schedules I, II, III, IV and V under the Federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, including opioids (such as codeine, morphine and hydromorphone), cannabinoids, amphetamines, barbiturates and anabolic steroids.16

References

- 1.Sketris I. Extending prescribing privileges in Canada. Can Pharm J. 2009;142(1):17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan S, Raymond C, Mooney D, Martin D. The Canadian Rx atlas. Vancouver (BC): Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health care in Canada, 2008. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002;288(4):462–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dragomir A, Côté R, Roy L. Impact of adherence to antihypertensive agents on clinical outcomes and hospitalization costs. Med Care. 2010;48(5):418–25. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d567bd. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glazier RH, Klein-Geltink J, Kopp A, Sibley LM. Capitation and enhanced fee-for-service models for primary care reform: a population-based evaluation. CMAJ. 2009;180(11):E72–81. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGhan WF, Stimmel GL, Hall TG, Gilman TM. A comparison of pharmacists and physicians on the quality of prescribing for ambulatory hypertensive patients. Med Care. 1983;21(4):435–44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hepler C, Strand L. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1990;47(3):533–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonna AP, Stewart D, West B, McCaig D. Pharmacist prescribing in the UK — a literature review of current practice and research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32(6):545–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chisholm-Burns MA, Graff Zivin JS, Lee JK. Economic effects of pharmacists on health outcomes in the United States: a systematic review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(19):1624–34. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100077. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fittock A. Non-medical prescribing by nurses, optometrists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, podiatrist and radiographers. Liverpool (England): National Prescribing Centre; 2010. Available: www.npc.co.uk/prescribers/resources/NMP_Quick-Guide.pdf (accessed Jan. 5, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondro W. Canada's doctors assail pharmacist prescribing. CMAJ. 2007;177(6):558. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emmerton L, Marriott J, Bessell T. Pharmacists and prescribing rights: review of international developments. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2005;8(2):217–25. et al. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberta College of Pharmacists. 2007. Health Professions Act Standards for Pharmacist Practice. Available: http://pharmacists.ab.ca/document_library/HPAstds.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alberta College of Pharmacists. 2007. Orientation to your new practice framework. Available: https://pharmacists.ab.ca/document_library/orientation_final.pdf (accessed Jan. 11, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Government of Canada. 2011. Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (S.C. 196, c.19) Available: http://laws.justice.gc.ca/PDF/Statute/C/C-38.8.pdf (accessed Feb. 11, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 17.College of Pharmacists of British Columbia. Orientation guide — medication management (adapting a prescription) Available: www.bcpharmacists.org/library/D-Legislation_Standards/D-2_Provincial_Legislation/1017-PPP58_OrientationGuide.pdf (accessed July 27, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Manitoba Pharmaceutical Association, The College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba, The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba. 2006. Continued care prescriptions from practitioners. Available: www.napra.org/Content_Files/Files/Manitoba/Continued-Care-Joint-Statement-April-2006-09.pdf (accessed Nov. 1, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 19.The New Brunswick Pharmaceutical Society. 2010. Regulations of the New Brunswick Pharmaceutical Society. Available: www.nbpharmacists.ca/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ezNCFfcjrSg%3d&tabid=244&mid=686 (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 20.The New Brunswick Pharmaceutical Society. 2008. Continued care prescriptions policy. Available: www.nbpharmacists.ca/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=KoPvpY80rtM%3D&tabid=261&mid=695 (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nova Scotia Department of Health. 2010. Nova Scotia Pharmacare programs — pharmacists' guide. Available: www.gov.ns.ca/health/pharmacare/pubs/Pharmacists_Guide.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prince Edward Island Legislative Council Office. Pharmacy Act: Continued Care Prescription Regulations. Available: www.gov.pe.ca/law/regulations/pdf/P&06-2.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newfoundland and Labrador Pharmacy Board. 2010. Medication management by community pharmacists. Available: www.nlpb.ca/Documents/Standards_Policies_Guidelines/SOPP-Medication_Management-June2010.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 24.College of Pharmacists of British Columbia. Amendment to orientation guide — medication management (adapting a prescription) Available: www.bcpharmacists.org/library/DLegislation_Standards/D-2_Provincial_Legislation/PPP58_AmendmentOrientationGuide.pdf (accessed July 27, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuksel N, Eberhart G, Bungard TJ. Prescribing by pharmacists in Alberta. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(22):2126–32. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberta College of Pharmacists. 2008. Guide to receiving additional prescribing authorization. Available: https://pharmacists.ab.ca/Content_Files/Files/APA_guide_final.pdf (accessed Nov. 1, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saskatchewan pharmacists adjust to new generic price regime with aid of additional compensation. Can Pharm J. 2011;144(4):156. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saskatchewan College of Pharmacists. 2010. Regulatory bylaw amendments pursuant to The Pharmacy Act, 1996. Available: www.napra.org/Content_Files/Files/Saskatchewan/ProposedPrescribingBylawsAwaitingtheMinisterofHealth.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manitoba Pharmaceutical Association. 2010 Pharmaceutical regulations policy document. Available: http://napra.ca/Content_Files/Files/Manitoba/RegsPolicyDocOct08.10.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ontario College of Pharmacists. Draft Bill 179 regulation. Available: www.ocpinfo.com/Client/ocp/ocphome.nsf/object/ExpSP+Regulation/$file/Draft_Bill_179_Regulation+.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists. 2011. Standard of practice: prescribing of drugs by pharmacists. Available: www.nspharmacists.ca/standards/pdf/prescribing-standards-ofpractice-january-2011.pdf (accessed Nov. 1, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynas K. Pharmacist regulator in Quebec develops proposals to bring prescribing authority more in line with other jurisdictions. Can Pharm J. 2010;143(3):120. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Law MR, Morgan SG. Paying pharmacies properly. The Mark. Available: www.themarknews.com/articles/1462-payingpharmacies-properly (accessed Jan. 10, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zarowitz BJ, Miller WA, Helling DK, et al. Optimal medication therapy prescribing and management: meeting patients' needs in an evolving health care system. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(11):1198. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buckley P, Grime J, Blenkinsopp A. Inter- and intra-professional perspectives on non-medical prescribing in an NHS trust. Pharm J. 2006;277(7420):394–98. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marra CA, Lynd L, Grindrod KA, et al. 2010. An overview of pharmacy adaptation services in British Columbia. Available: www.health.gov.bc.ca/pharmacare/pdf/COREAdaptationOverview.pdf (accessed Dec. 21, 2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law MR, Morgan SG, Majumdar SR, et al. Effects of prescription adaptation by pharmacists. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):313. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]