Abstract

Background: Medication errors can cause substantial harm to patients and may lead to significant costs within a health care system. As such, there is value in identifying patient-related risk factors for medication errors. The objectives of this study were to identify patient-related risk factors associated with self-reported medication errors and to determine whether the risk factors differed between hospital and community settings.

Methods: The Commonwealth Fund's 2008 International Health Policy Survey of chronically ill patients in 8 countries was the primary data source. Univariate analyses were used to determine significant explanatory variables (p < 0.05) for inclusion in weighted logistic regression models. Two regression models were developed: one to identify overall patient-related risk factors and the other to determine whether these factors differed between hospital and community settings.

Results: The final study population consisted of 9944 adults. Patient-related risk factors significantly associated with self-reported medication errors were the number of medications being taken, sex, age and country of residence. Approximately 4 out of every 5 self-reported medication errors occurred in the community setting.

Conclusions: A substantial percentage of patients with chronic diseases in the countries covered by the survey experienced medication errors, with most errors occurring in the community setting. Several patient-related risk factors were associated with these errors. Greater emphasis on national incident reporting systems and greater sharing of knowledge across nations could help to identify strategies to overcome these problems. More specifically, strategies to increase reporting of and learning from medication errors, as well as education about potential patient-related risk factors, are recommended.

Introduction

Medication errors occur as a result of either human mistakes or system flaws.1,2 Several system-based risk factors contributing to medication errors have been identified, including performance deficit, lack of adherence to procedures and protocols, inaccurate or omitted transcription of prescription details, poor documentation, knowledge deficit and calculation error.3 Work-related environmental factors identified as risk factors for medication errors include overall workload, interruptions, ineffective communication, distractions and high volumes of medications administered to patients.4,5

KEY POINTS.

Medication errors are costly in terms of harm to patients and increased burden on health care systems.

Multiple factors, including both system and patient-related, lead to the occurrence of medication errors.

This large international sample has shown that patient-related factors increase patients' risk for a self-reported medication error.

This study identifies that a higher rate of self-reported medication errors occur in the community setting and supports the need for a community-based medication error reporting system.

POINTS CLÉS.

Les erreurs de médicaments sont coûteuses, tant sur plan des préjudices causés aux patients que de l'accroissement du fardeau pour les systèmes de soins de santé.

De nombreux facteurs, liés à la fois au système et aux patients, sont à l'origine des erreurs de médicaments.

Ce vaste échantillon international montre que les facteurs liés aux patients augmentent le risque pour les patients d'erreurs de médicaments déclarées par l'intéressé.

Cette étude révèle également que le taux d'erreurs de médicaments déclarées par l'intéressé est plus élevé dans les pharmacies communautaires, ce qui vient appuyer l'importance d'instaurer un système de déclaration des erreurs de médicaments dans les pharmacies communautaires.

In addition to the system factors that have been linked to medication errors, researchers have also examined patient-related factors. For example, an analysis of 2 databases from the United States showed that the odds of prescribing an inappropriate medication with potential to cause an adverse event were double in women, relative to men.6 Older age has also been identified as a risk factor. The US Food and Drug Administration reported that more than half of fatal medication errors occurred in individuals age 60 years or older,7 and people in this age group are most at risk for medication errors and death from medication errors.8 A third patient-related characteristic linked to the occurrence of medication errors is a high number of prescribed medications. Indeed, polypharmacy has been cited as a risk factor contributing to increased morbidity and mortality.9 In a recent literature review, Easton et al.10 identified the patient populations at highest risk for medication errors as older patients, those with serious health conditions, those taking multiple medications, those using high-risk medicines and those being transferred between community and hospital care. Finally, a study examining risk factors for medication errors among noninstitutionalized ambulatory patients with chronic medical conditions in Jordan identified a link between the occurrence of medication errors, the patient's literacy level and knowledge regarding his or her medications and their resultant adverse events.11

Although research on medication safety has increased in recent years, studies in the community setting have been limited. Nonetheless, evidence suggests substantial under-reporting of medication errors in community pharmacies, which affects community pharmacists' ability to learn from these events12 and to improve their dispensing systems. While under-reporting makes it impossible to determine the exact number of incidents occurring each year, it has been estimated that about 7 million medication incidents occurred in community pharmacies in Canada in 2009.13

The objectives of this study were to identify patient-related risk factors associated with self-reported medication errors and to determine whether these risk factors differed between the hospital and community settings.

Methods

A secondary analysis was performed on data collected during the Commonwealth Fund's 2008 International Health Policy Survey.14 This survey was conducted in 8 countries: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. Eligible participants were those 18 years of age or older who reported at least one of the following criteria in the previous 2 years: poor or fair health, illness, disability, admission to hospital or major surgery. The telephone survey was conducted by Harris Interactive Inc. The average time for each interview was 17 minutes. The analysis used weighted data (based on recent census data from each nation) in the final samples to reflect the demographic distribution of adult populations in each country. Complete survey methods, along with average rates of errors, top-line findings and other results, have been reported previously.15 The Commonwealth Fund granted permission to use the raw survey data for the analysis reported here.

The database was explored using frequency tests on the entire sample. The relationships among the primary outcome, self-reported medication errors and hypothesized risk factors were explored with weighted logistic regression. Participants self-reported the occurrence of medication errors and identified whether the medication error occurred in hospital; errors not identified as occurring in hospital were deemed to have occurred in the community setting. The potential risk factors chosen for exploration in this study were based on previous literature, theory or hypothesis. The following independent variables were explored: number of medications taken, sex, age, country of residence and presence of a regular doctor. Univariate analysis was performed for each of the independent variables and only significant explanatory variables (p < 0.05) were included in the weighted logistic regression model. The first weighted logistic regression was limited to participants who were taking medications, to identify those who reported a medication error in the past 2 years. The purpose of this regression model was to assess the effect of patient-related risk factors on the occurrence of a medication error, regardless of the setting where the error occurred. A second weighted logistic regression model included only participants who reported having experienced a medication error. For the purpose of this analysis, the number of medication errors per person was not considered relevant and therefore each person with occurrence of one or more errors was counted only once. In addition, the odds ratio (OR) for each explanatory variable was calculated to determine the relative risk of experiencing an error, given each potential explanatory factor. Goodness of fit was determined using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Data analysis was performed using PASW Statistics, version 18.0.

Results

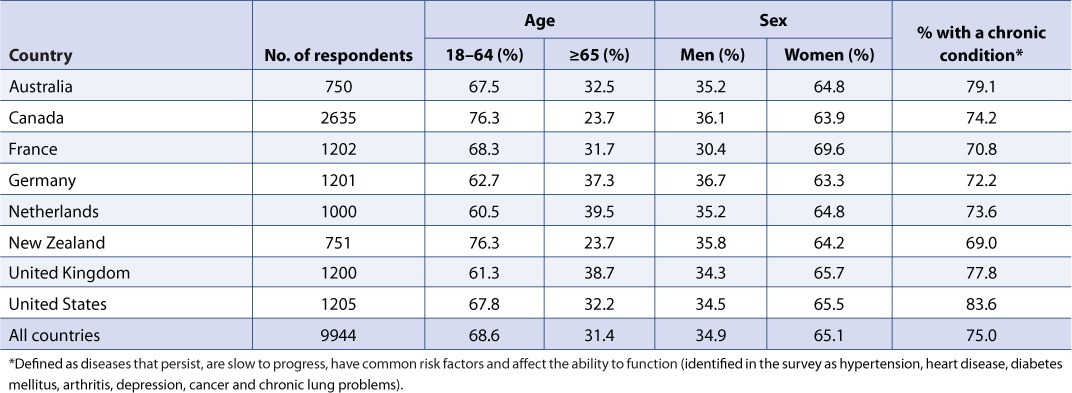

The study population consisted of 9944 adults 18 years of age or older from 8 countries (Table 1). Among the 7675 people who reported taking medications regularly, 732 reported one or more medication errors (Table 2). The percentage of respondents reporting medication errors per country ranged from 4.7% in Germany to 14.2% in the United States.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents to the Commonwealth Fund's 2008 International Health Policy Survey, by country

TABLE 2.

Medication errors for patients receiving medications, by country

Patient-related risk factors for self-reported medication errors

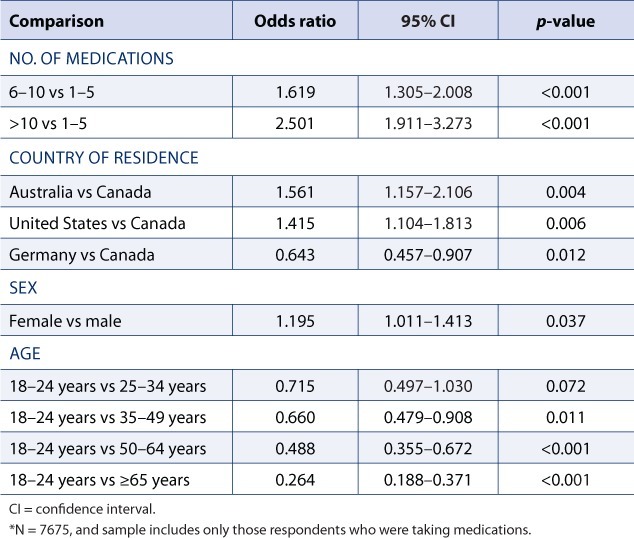

Of the 5 patient characteristics tested in the univariate analysis, presence of a regular doctor was not significantly associated with occurrence of a medication error. The remaining 4 patient characteristics (number of medications, sex, age and country of residence) were significantly associated with occurrence of an error and were entered into the weighted logistic regression model as explanatory variables for the 7675 participants who reported taking at least one medication. The odds for occurrence of a self-reported medication error were greater for respondents who were taking between 6 and 10 medications than for those taking between 1 and 5 medications (OR 1.619, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.305–2.008; p < 0.001). For respondents who were taking more than 10 medications, the risk of error was even higher, relative to those taking up to 5 medications (OR 2.501, 95% CI 1.911–3.273; p < 0.001) (Table 3). Relative to respondents living in Canada, those in Australia (OR 1.561, 95% CI 1.157–2.106; p 0.004) and the United States (OR 1.415, 95% CI 1.104–1.813; p = 0.006) had a higher risk of self-reported medication errors, whereas those in Germany had a lower risk (OR 0.643, 95% CI 0.457–0.907; p = 0.012). The odds of experiencing a self-reported medication error were greater for women than for men (OR 1.195, 95% CI 1.011–1.413; p = 0.037) and were lower for individuals 18 to 24 compared to those 35–49 (OR 0.660, 95% CI 0.479–0.908; p= 0.011), 50 to 64 years (OR 0.488, 95% CI 0.355– 0.672; p < 0.001), or 65 years or older (OR 0.264, 95% CI 0.188–0.371; p < 0.001). The result of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was nonsignificant (χ2 = 12.805, p = 0.118), which indicates that the model fit the data well.

TABLE 3.

Weighted logistic regression model of patient-related risk factors for self-reported medication errors in either the hospital or the community setting *

Patient-related risk factors for community versus hospital-based medication errors

The second logistic regression model focused on respondents who reported having experienced at least 1 medication error in the previous 2 years. In total, 1723 medication errors were reported by 732 participants. For this analysis, the focus of interest was not the number of errors but their origin; therefore multiple self-reported errors from a single respondent were counted as 1 incident. For 15 respondents, the data were incomplete and could not be analyzed. Therefore, 717 respondents were included in the analysis, with 570 (79%) errors occurring in the community setting and 147 (21%) in the hospital setting. For this analysis, the presence of a regular doctor was not a significant contributing factor. The remaining 4 patient characteristics (number of medications, sex, age and country of residence) were identified as significant through the univariate analysis and were entered into the weighted logistic regression model as explanatory variables for the 717 participants who reported at least one medication error.

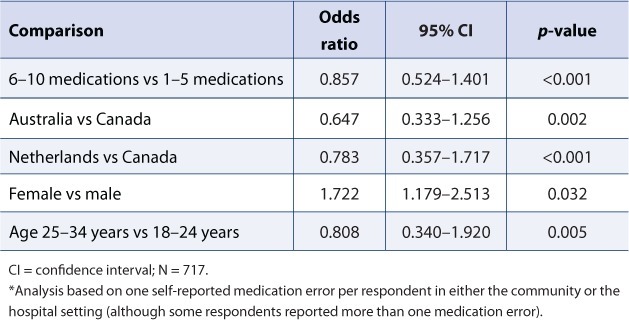

The analysis showed that women had a higher risk than men of experiencing a medication error in the community rather than the hospital setting (OR 1.722, 95% CI 1.179–2.513; p = 0.032) (Table 4). Results for the other variables were statistically significant (number of medications, p < 0.001; age, p = 0.005; country of residence, p ≤ 0.002); however, in each of these cases, the 95% confidence interval included the value 1.0. Further, if a confidence interval includes 1.0, then it is not a significant result, since 1.0 means no difference. The result of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was nonsignificant (χ2 = 6.925, p = 0.545), which indicates that the model fit the data well.

TABLE 4.

Weighted logistic regression model of patient-related risk factors for self-reported medication errors in the community setting versus the hospital setting *

Discussion

In the Commonwealth Fund's 2008 International Health Policy Survey, a substantial proportion of patients with chronic disease in all 8 countries reported experiencing medication errors. Not only do such errors negatively affect overall population health, but they also impose a financial burden on health care systems. In Canada, the cost of preventable drug-related morbidity and mortality in older adults was estimated at C$11 billion in 2001.16 In the United States, a conservative estimate of US$3.5 billion annually has been attributed to medication errors.17 In Australia, inappropriate medication use, including errors, has been shown to cost about A$380 million per year in the public health system alone.18 Improvements in the accuracy and tracking of costs related to medication errors, on both a national and an international scale, are warranted.

Regarding the setting in which errors are most likely to occur, there were approximately 4 self-reported medication errors in the community setting for every 1 self-reported medication error in the hospital setting. It is important to recognize that the study population consisted of people with chronic conditions frequenting emergency departments and hospitals. Given the large percentage of errors that occurred in the community, proper monitoring and reporting in this setting appear to be lacking. A recommendation for future practice would be the development of national reporting systems for the documentation of community-based medication errors. It is envisioned that a national reporting system would provide a rich database that could identify trends in the occurrence of errors and thus permit the focus on modifiable items or the ability to make recommendations for practice change to attempt to reduce their occurrence. The reduced availability of valid data within the community means that researchers must collate data from a variety of sources, including poison control centres, pharmacies, physician offices and emergency departments. However, with no consistent reporting guidelines or processes, data collected in this manner are potentially inconsistent or incomplete.

The recent development of an online national reporting platform for community pharmacies in Canada represents an important advancement with respect to the availability of community-based data. The Community Pharmacy Incident Reporting Program (www.cphir.ca) was launched by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada in 2010 in order to create a national platform for community pharmacy practitioners to learn from anonymous incident reporting.19 Learning from these medication incidents and improving systems and practice accordingly form the mandate of a Canadian research program known as SafetyNET-Rx (www.safetynetrx.ca). This continuous quality improvement program, which is tailored specifically to community pharmacy practice, encourages pharmacies to identify, report and analyze medication errors and near misses and to assess and improve key processes to prevent their recurrence.

The adoption of reporting systems by other nations would not only help in identifying common system issues that need to be changed to reduce the occurrence of medication errors in the community, but would also provide information about trends related to specific brands of medication and age. Such reporting systems would also provide a means of comparing best practices among nations and of learning from international best practices. Additionally, this would provide a means of tracking implementation of new medication delivery systems, quality advancement and system-based costs related to the occurrence of errors.

One limitation of this study was the use of secondary data. As such, it was impossible to further explore the characteristics of the communities and hospitals where the errors occurred. Therefore, descriptive data about the types of medication delivery systems and reporting systems in use, as well as the safety culture in each country, are missing. Furthermore, the secondary data set did not specify the medications involved in particular errors or the reason for each error. Availability of these types of information might have permitted recommendations for changes in practice and/or policy. As well, the use of secondary data did not allow for direct interaction with participants (e.g., to ask specific questions or to clarify particular findings). Nonetheless, the survey and the resulting database provided valid, reliable and in-depth data for a large sample of participants covering a broad geographic range.

Another potential limitation was the reliance on self-reporting of errors. Previous research has demonstrated that medication errors are under-reported.20 As such, it is virtually impossible to know the true number of medical errors that occurred within this population during the defined study period. In addition, the survey asked participants to reflect on past occurrences of error, which presents the possibility of recall bias. Nonetheless, given that errors in both the community and the hospital were of interest for this study, the patient is the optimal reporter. Furthermore, given the known under-reporting of errors, a review of clinical records would not allow accurate description of the medication error rate and might not accurately capture medication errors in the community.

The results of this study reveal that patient-related risk factors contribute to the occurrence of self-reported medication errors. The number of medications that a person is taking and the person's age, sex and in some instances country of origin affect the occurrence of medication errors. These results suggest that women who are taking multiple medications are at the greatest risk for self-reported medication errors. Acknowledgement of these patient-related characteristics might lead to additional vigilance and might alert health care providers to potential risks. Further research is warranted to identify and incorporate best practices to prevent medication errors. Finally, because most self-reported medication errors occurred in the community setting, the development of national reporting systems for tracking community-based medication errors is also required.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cathy Schoen, Michelle Doty, Robin Osborn, David Squires and Kristof Stremikis from the Commonwealth Fund for providing the data set and input on the final draft of this manuscript. The authors also thank Dr. Kara Thompson for assistance with the statistical design and analysis and Alison DeLory for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Aspden P, Wolcott JA, Bootman JL, Cronenwett LR, editors. Preventing medication errors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leape LL. Preventing medication errors in pediatric and neonatal patients. In: Cohen M, editor. Medication errors. Washington (DC): American Pharmacists Association; 2007. pp. 469–92. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowley E, Williams R, Cousins D. Medication errors in children. A descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopeia. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2001;26:627–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sears KA. The relationship between the nursing work environment and the occurrence of reported paediatric medication administration errors [dissertation] Toronto (ON): University of Toronto; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stratton KM, Blegen MA, Pepper G, Vaughan T. Reporting of medication errors by pediatric nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2004;19:385–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goulding MR. Inappropriate medication prescribing for elderly ambulatory care patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:305–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stöppler MC. Medication error reports. In: Marks JW, editor. The most common medication errors. Washington (DC): US Food and Drug Administration; 2006. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips J, Beam S, Brinker A, et al. Retrospective analysis of mortalities associated with medication errors. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58:1835–41. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.19.1835. Erratum in Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001;58:2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honig PK, Cantilena LR. Polypharmacy. Pharmacokinetic perspectives. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;26:85–90. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Easton K, Morgan T, Williamson M. Medication safety in the community: a review of the literature. Sydney (Australia): National Prescribing Service; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shishani K, Mrayyan MT. Risk factors for medication errors among chronically ill adults. J Pure Appl Sci. 2007;4(2):95–109. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scobie AC, Boyle TA, MacKinnon NJ, et al. Perceptions of community pharmacy staff regarding strategies to reduce and to improve the reporting of medication incidents. Can Pharm J. 2010;143(6):296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle TA, Mahaffey T, MacKinnon NJ, et al. Determinants of medication incident reporting, recovery, and learning in community pharmacies: a conceptual model. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2011;7(1):93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peugh J, Choureiri K, Sesetyan T. The 2008 Commonwealth Fund international health policy survey. New York (NY): Harris Interactive Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoen C, Osborn R, How SKH, et al. In chronic condition: experiences of patients with complex health care needs, in eight countries, 2008. Health Aff. 2009;28:w1–w16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidney T, MacKinnon NJ. Preventable drug-related morbidity and mortality in older adults: a Canadian cost-of-illness model. Geriatr Today. 2001;4:120. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Stoddard GJ, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events: a 10-year analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1161–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Second national report on patient safety: improving medication safety. Sydney (Australia): Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung P, Poon C, Ho C. Medication safety in community pharmacies. Pharmacyconnection. 2010;July/August:35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayo AM, Duncan D. Nurse perceptions of medication errors: what we need to know about patient safety. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19:209–17. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]