Introduction

Research has shown that patient-centred pharmacist interventions can be effective in a wide range of practice settings and disease states.1–6 In recent years, several Canadian jurisdictions have begun to pay for pharmacist-led clinical services such as medication reviews, minor ailment management and smoking cessation counselling.7 Unfortunately, it has been widely reported that uptake of these services is often unimpressive, even when remuneration is available. 8,9 Several barriers to practice change have been previously identified, including pharmacists' time constraints, patient apathy, limited support from physicians and pharmacy managers, disruption of workflow, inadequate reimbursement and even the culture of the pharmacy profession.10,11 Consequently, progress towards realizing pharmacists' full potential within the health system continues to be very slow.10

However, some pharmacists do embrace change and successfully implement new interventions, despite the systemic barriers that exist.12 These individuals take on risks and new responsibilities to defy the cultural norms set by their colleagues. Unfortunately, little is known about these early-adopters and what makes them succeed. A detailed evaluation of the participants in the pilot of the ADAPT (ADapting pharmacists' skills and Approaches to maximize Patient's drug Therapy effectiveness) Education Program may provide some insight.

This paper describes the ADAPT pilot participants' demographics, characteristics, preparedness, motivation and reasons for participating. The goal of this paper is to better understand the pharmacists who were willing to engage with this novel, timeintensive education program. This information can provide valuable insight into the types of pharmacists striving to change their practice.

What is ADAPT?

The ADAPT education program was developed to address pharmacists' need to incorporate patient care skills into practice. ADAPT is based on research describing the knowledge, skills and attitudes pharmacists require to optimize medication outcomes and collaborate with other health providers.13–15 ADAPT incorporates best practices in online and hands-on training, enabling pharmacists to integrate new skills into practice.13,16–18 The program consists of 7 web-based modules (addressing skills such as patient interviewing, collaboration, documentation and decision-making) moderated by experienced pharmacists and uses teaching modalities such as lectures, videos, practice-based activities, patient cases and self/peer assessments. As part of the pilot, a final face-to-face workshop further enhanced the transfer of skills into practice. A full description of ADAPT is available elsewhere.19 The ADAPT pilot began in summer 2010 and concluded in February 2011.

Recruitment and evaluation of pilot participants

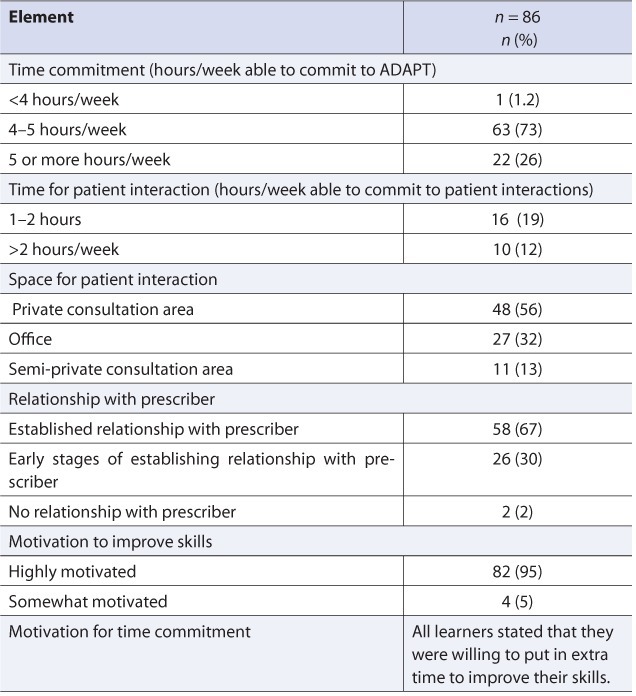

The ADAPT pilot was open to all Canadian pharmacists and was advertised through e-mails sent to Canadian Pharmacists Association and Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists members and through listserv postings to members of the Canadian Primary Care Pharmacists Specialty Network. Those interested completed a self-assessment that provided feedback regarding suitability for the program and obtained consent to participate in the evaluation. It was explained during this process that participation in ADAPT would require regular application of skills within participants' practice sites, significant time commitment (e.g., 4–5 hours/week) and appropriate space (e.g., private counselling area). Program tuition was waived for pilot participants.

Information collected from the self-assessment process was used to select individuals perceived to be most likely to succeed in the program (e.g., those with the most time, space and motivation to complete the course) and also to ensure a balanced representation from various regions and practice settings. Of the 271 pharmacists who completed the self-assessment and registered for the pilot, 90 were selected anonymously and offered admission.

The selected pilot participants were evaluated using a mixed-methods assessment. The descriptive quantitative data from the self-assessment and registration process (i.e., demographics, participation suitability) were considered together with qualitative data from the orientation module discussion board, in which participants introduced themselves. The qualitative analysis began with trying to understand motivation for participation. The research associate read discussion board posts and created syntheses of themes. The primary investigator and research assistant read discussion board posts and syntheses, adding as needed. Summaries were circulated to investigators and discussed at team teleconferences. The study was approved by the Bruyère Continuing Care Research Ethics Board.

Results

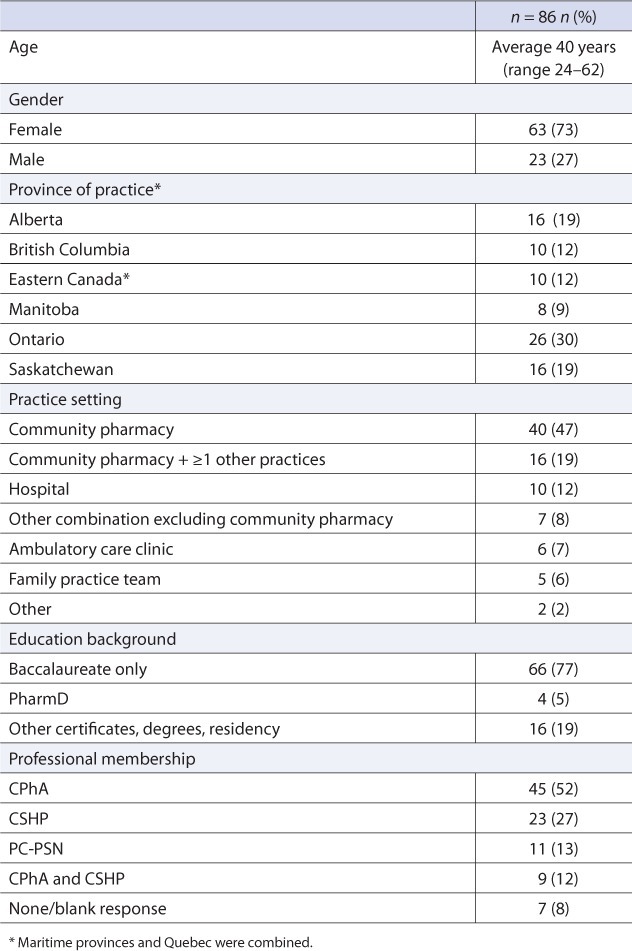

Eighty-six of the 90 pharmacists (95.6%) who were offered admission chose to participate in the ADAPT pilot. Learner demographics are outlined in Table 1. The self-assessment component's preparedness and motivation results are outlined in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacist demographics

TABLE 2.

Pharmacist preparedness and motivation

Seventy-one of the 86 participants (82.6%) introduced themselves and described their motivations for participating by posting to the orientation module discussion board. The postings revealed several themes. The first was that the majority of participants were busy, adventurous, lifelong learners. Many had earned additional professional certifications (e.g., Certified Diabetes Educator). In their personal lives, most participated in a variety of time-consuming and adventurous extracurricular activities (e.g., travel, sports, drama) despite having young families.

We have 2 boys and are getting ready to start hockey season… and I am currently in training to run a half marathon.

Learners were also future-oriented and highly motivated to embrace change. Many wanted to improve their professional skills to provide better patient care and prepare themselves for changes in the profession.

I like to be ahead of the “wave” and since I am looking forward to our expanded role… I am looking for every possible opportunity to get better prepared.

Learners were also highly motivated to improve their skills, but varied in the degree to which they could articulate their learning needs. Some stated specific skills they wished to improve, but many others had very general goals.

Finally, learners came to the pilot with varied previous experiences with online learning. The majority looked forward to the upcoming peer interactions within ADAPT, but varied in their degree of engagement in the early discussion.

I am comfortable with the online environment, but this is my very first post on a discussion board!

Discussion

These data suggest that the ADAPT participants were a highly selected volunteer group who may not represent most pharmacists practising in Canada. Compared with a 2009 national pharmacist survey performed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, ADAPT pharmacists were slightly younger (average age 40.0 vs 43.6) and included a higher proportion of women (73.3% vs 59.2%). ADAPT pharmacists had more education than typical practising pharmacists,20 with almost onequarter (23.3%) of ADAPT pharmacists having training beyond a baccalaureate degree, compared with 5.8% of Canadian pharmacists.20 In addition, 46.5% of ADAPT pharmacists reported practising exclusively in community pharmacies, compared with 75.5% of Canadian pharmacists.20 This difference is attributed to 26.7% of ADAPT pharmacists who reported practising in a “combination” of practice settings (compared with 2.5% in Canada).20 Canadian pharmacists have also been previously described in the literature as being risk averse, afraid of change, lacking confidence and “paralyzed in the face of ambiguity.”11,21 This is a stark contrast to ADAPT participants, who were adventurous risk takers, hungry for change and keenly interested in acting on that desire for change by taking a leap of faith in a new online educational program.

In his book “Diffusion of Innovations,” Rogers describes “early adopters” as being younger, more often seen as opinion leaders and more educated than their peers.22 ADAPT participants, who were younger and more educated than the typical Canadian pharmacist, bear a striking resemblance to this description. Consequently, we believe that this paper provides a detailed description of a group of early adopters (of a novel education program) who have not previously been well characterized within the pharmacy profession.

ADAPT was successful in engaging these early adopters of educational initiatives; however, future research must focus on how we can similarly engage early adopters of practice change innovations. Leaders within the profession have suggested that pharmacy practice implementation research and knowledge translation initiatives shift away from recruiting “typical pharmacists” and begin focusing on the “early adopters” of practice innovations, in an effort to better understand how some pharmacists are able to change when so many others do not succeed over the long term.23 Assuming this is a direction that practice change researchers choose to follow, the characteristics of the ADAPT participants described in this paper will assist in the identification and recruitment of early adopters into future practice change initiatives.

Conclusion

The pilot cohort of ADAPT represents a group of pharmacists who recognize the need for change in pharmacy practice, are eager to take on new responsibilities, are motivated to engage in ongoing education and see the need to improve patient care. This study describes the characteristics of these early adopters. Future implementation research and knowledge translation efforts should be directed towards this group and their needs studied more closely, to facilitate successful pharmacy practice change.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Natalie Kennie-Kaulbach and Pia Zeni Marks, who also contributed to data analysis.

Footnotes

Financial acknowledgements: The Canadian Pharmacists Association's (CPhA) ADAPT program was developed in collaboration with the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists (CSHP) and the members of the CPhA-CSHP Primary Care Pharmacy Specialty Network. ADAPT is funded in part by Health Canada under the Health Care Policy Contribution Program.

References

- 1.Chisholm-Burns MA, Lee J, Spivey CA. US pharmacists' effect as team members on patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Care. 2010;48:923–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e57962. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koshman SL, Charrois TL, Simpson SH. Pharmacist care of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:687–94. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.687. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, Einarson TR. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part II: systematic review and meta-analysis in hypertension management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1770–81. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado M, Nassor N, Bajcar J. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part III: systematic review and meta-analysis in hyperlipidemia management. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1195–1207. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K618. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santschi V, Chiolero A, Burnand B. Impact of pharmacist care in the management of cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1441–53. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.399. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuyuki R, Johnson J, Teo KK. A randomised trial of the effect of community pharmacist intervention on cholesterol risk management: the Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP) Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1149–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1149. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Battu K, Emberley P. Pharmacists' medication management services: Environmental scan of Canadian and international services. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2010. Available: http://blueprintforpharmacy.ca/docs/pdfs/environmental-scan-of-pharmacy-services_cpha_dec19_2011.pdf (accessed June 1, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolovich L, Gagnon A, McAiney C. Initial pharmacist experience with the Ontario-based MedsCheck program. Can Pharm J. 2008;141:339–45. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broadview Applied Research Group. Alberta Pharmacists' Association; 2010. Alberta pharmacy practice models initiative: evaluation report. Available: www.rxa.ca/PharmacyGrants/PPMI.aspx (accessed May 29, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Task Force on a Blueprint for Pharmacy. Blueprint for pharmacy: the vision for pharmacy. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2008. Available: http://blueprintforpharmacy.ca/docs/pdfs/2011/05/11/BlueprintVision.pdf?Status=Master. (accessed January 10, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal M, Zubin A, Tsuyuki R. Are pharmacists the ultimate barrier to pharmacy practice change? Can Pharm J. 2010;143:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Management Committee, Moving Forward: Pharmacy Human Resources for the Future. Innovative pharmacy practices. Volume II: Profiles of pharmacy practices. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2008. Available: http://blueprintforpharmacy.ca/docs/default-documentlibrary/2011/04/19/Innovative_Pharmacy_Practices_Volume_II_final.pdf?Status=Master (accessed September 10, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin Z, Dolovich L, Lau E. Teaching and assessing primary care skills: the family practice simulator model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69:500–7. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrell B, Pottie K, Haydt S. Integrating into family practice: the experiences of pharmacists in Ontario, Canada. Int J Pharm Pract. 2008;16:309–15. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blueprint for Pharmacy: Consultation Report, February 2008. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2008. Available: http://blueprintforpharmacy.ca/docs/pdfs/bpconsultreport---feb-08---on-web.pdf (accessed September 10, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor L, Abbott PA, Hudson K. E-learning for health-care workforce development. Yearb Med Inform. 2008:83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raza A, Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. Best evidence continuous medical education. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:683–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook DA, Triola MM. Virtual patients: a critical literature review and proposed next steps. Med Educ. 2009;43:303–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell B, Dolovich L, Emberley P. Designing a novel continuing education program for pharmacists: lessons learned. Can Pharm J. 2012;145:e7–e16. doi: 10.3821/145.4.cpje7. et al. Available: www.cpjournal.ca/doi/pdf/10.3821/145.4.cpje7 (accessed September 7, 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pharmacists in Canada, 2009. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2010. Available; https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?pf=PFC1563&lang=en&media=0 (accessed September 10, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin Z, Gregory PA, Martin JC. Negotiation of interprofessional culture shock: the experience of pharmacists who become physicians. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:83–93. doi: 10.1080/13561820600874817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. New York (NY): The Free Press (A Division of Simon & Schuster Inc.); 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Power B. What's the real barrier to change in pharmacy? Can Pharm J. 2010;143:43. [Google Scholar]