Abstract

Protein insolubility often poses a significant problem during purification protocols and in enzyme assays, especially for eukaryotic proteins expressed in a recombinant bacterial system. The limited solubility of replication factor C (RFC), the clamp loader complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, has been previously documented. We found that mutant forms of RFC harboring a single point mutation in the Walker A motif were even less soluble than the wild-type complex. The addition of maltose at 0.75 M to the storage and assay buffers greatly increases protein solubility and prevents the complex from falling apart. Our analysis of the clamp loading reaction is dependent on fluorescence-based assays, which are environmentally sensitive. Using wt RFC as a control, we show that the addition of maltose to the reaction buffers does not affect fluorophore responses in the assays or the enzyme activity, indicating that maltose can be used as a buffer additive for further downstream analysis of these mutants.

Keywords: DNA replication, Replication factor C, Proliferating cell nuclear antigen, Protein solubility, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, DNA repair

Introduction

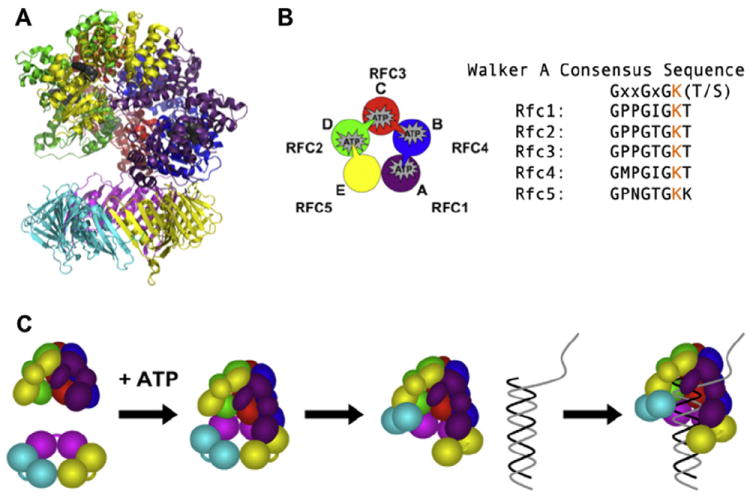

Clamps and clamp loaders are essential components of the replisome. During replication the clamp serves to tether the polymerase to the DNA template so that the rate of DNA synthesis is limited only by the rate of nucleotide incorporation [1-3]. The clamp loader is responsible for loading the clamp onto DNA. The eukaryotic clamp, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA),1 is a toroidal homotrimer while the eukaryotic clamp loader, replication factor C (RFC), is a heteropentamer (Fig. 1a) [4,5]. RFC belongs to a family of proteins known as AAA + ATPases, which utilize the energy from ATP hydrolysis to perform cellular functions [6-8]. At least four of the five RFC subunits are able to bind ATP (Fig. 1b) [6,9]. Proteins within this family share several structural motifs that serve to coordinate and promote ATP binding and hydrolysis. Three of these are the Walker A, Walker B, and arginine finger motifs and they are involved in ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis, and sensing bound ATP, respectively [10-12]. The clamp loading reaction is complex, involving many interactions and conformational changes. Simplistically, RFC, in the presence of ATP, binds and opens PCNA, and then binds DNA, allowing the formation of a ternary complex (cartoon schematic Fig. 1c). Formation of this complex triggers ATP hydrolysis, promoting loading of the clamp onto DNA and RFC dissociation. The functions these motifs play during the clamp loading reaction are generally only analyzed from an endpoint assay such as the number of clamps loaded onto DNA or the ability to support processive DNA synthesis. Fluorescence-based assays developed in our laboratory can be used to monitor specific steps within the clamp loading reaction and determine the precise role individual residues play. For example, rather than simply evaluating the effects of a mutation on the overall efficiency of clamp loading or DNA replication, these assays identify specific steps, such as DNA binding or clamp opening, that are affected by the mutation. Clamp binding and opening are measured in two different assays. In the clamp binding assay, the fluorescence of an environmentally sensitive fluorophore covalently attached to the surface of PCNA increases when RFC binds [13,14]. In the clamp opening assay, two fluorophores, juxtaposed on either side of the clamp monomer interfaces, are quenched when the clamp is closed, and the fluorescence increases when RFC opens the clamp and “pulls apart” the two fluorophores [13,15]. DNA binding is measured by monitoring the increase in anisotropy that occurs when proteins bind the fluorescent-labeled DNA [16-18].

Fig. 1.

RFC structure and clamp loading reaction schematic. (A) Ribbon diagram of the ScRFC/PCNA complex structure (PDB ID: 1SXJ) with α-helices shown as coils, β-sheets as arrows, and bound nucleotide as dark gray spheres is shown. The RFC subunits are: Rfc1 (purple), Rfc2 (green), Rfc3 (red), Rfc4 (blue) and Rfc5 (yellow). Each PCNA monomer is shown as a different color. (B) A cartoon depicting the arrangement of subunits and arginine finger interactions in RFC using the same color scheme as in panel A is shown. The arginine finger motif is shown as a wedge-like protrusion extending to the ATP site of the neighboring subunit. The Walker A consensus sequence is aligned with the individual sequence for each RFC subunit. The conserved Lys residue that was mutated to Ala for these studies is shown in orange. (C) Schematic of the clamp loading reaction in the presence of ATP leading to the formation of a ternary complex (RFC▪PCNA▪DNA) prior to ATP hydrolysis is shown.

To identify the role that the conserved Lys residue from the Walker A motif (consensus sequence with Lys shown in orange, Fig. 1b) plays in clamp loading, this residue was mutated to Ala. This mutation is predicted to prevent ATP binding [9,12]. Even though the Rfc5 subunit has been shown to bind ATP [5,6], there is no arginine finger motif extending from an adjacent subunit to create an active site for ATP hydrolysis (Fig. 1b). For this reason, we have chosen only to mutate residues within four subunits: Rfc1, Rfc2, Rfc3, and Rfc4. Because different genes encode all four subunits, this can be done site-specifically to create four different mutant RFC complexes and determine whether individual ATP binding sites have distinct functions. As no laboratory has been able to purify the human proteins in the quantities needed for these assays, we chose Saccharomyces cerevisiae as our model system. Using a dual vector system, all five RFC subunits were co-expressed in Escherichia coli and the assembled complex was purified using ion exchange and affinity chromatography [4,11,19]. Although much of the protein is present in the insoluble fraction, at least 5 mg of mutant RFC per liter of expression media is in the soluble fraction. Solutions of purified mutant complexes at high concentrations were cloudy, and at lower concentrations in anisotropy experiments a high background due to light scattering was observed, both of which indicate that the mutant proteins precipitate. Given that protein precipitation was likely occurring under our assay conditions, quantitative measurements of the activities of mutant complexes could not be made reliably. Therefore, different buffer conditions were evaluated to identify additives that would increase protein solubility and limit precipitation while not having an adverse effect on our fluorescence-based assays under equilibrium or pre-steady state analysis.

Materials and methods

Buffers and reagents

Assay buffer consists of 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 8 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 0.5% or 4% glycerol where indicated, and 750 mM maltose (when present). Storage buffer for PCNA contains 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. Storage buffer for wild-type RFC (wt RFC) contains 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 300 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. Storage buffer for RFC4GAT is the same as for RFC except for the addition of 750 mM maltose.

Nucleotides and oligonucleotides

Concentrations of ATP (GE Healthcare) diluted with 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and ATPγS diluted with water (Roche Diagnostics) were determined by measuring the absorbance at 259 nm and using an extinction coefficient of 15,400 M−1 cm−1. Synthetic oligonucleotides were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies and purified by 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The sequences of the 60-nucleotide template and the complementary 30-nucleotide primer are as follows: 5′-(5AmMC6)TTC AGG TCA GAA GGG TTC TAT CTC TGT TGG CCA GAA TGT CCC TTT TAT TAC TGG TCG TGT-3′ and 5′-ACA CGA CCA GTA ATA AAA GGG ACA TTC TGG-3′, where 5AmMC6 is a T with a C6 amino linker that was covalently labeled with X-Rhodamine (RhX) (Invitrogen) as described [16-18]. Primed templates were annealed by incubating the 30-nucleotide primer with the 60-nucleotide template at 85 °C for 5 min and then allowing the solution to slowly cool to room temperature. For all assays, the molar ratios of primer to template were 1.2:1 in annealing reactions.

Proteins

The DNA constructs for expressing wt RFC, each of the mutants, and PCNA were obtained from M. O’Donnell (Rockefeller University) [19,11]. PCNA was expressed, purified, and labeled as previously described [20] with minor modifications [13]. Fluorophores for labeling PCNA were purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen). RFC Walker A mutants are named based upon the subunit containing the mutation (for example, if the RFC4 subunit has the Lys to Ala substitution, the complex would be termed RFC4GAT). RFC and RFC4GAT (both with 283 amino acid truncation of the N terminus of RFC1) were expressed and purified as previously described [4,19,11] with minor modifications (A. Chiraniya, unpublished).

Size exclusion chromatography

Protein standards were resuspended in either RFC or RFC4GAT storage buffer as per the manufacturer’s instructions (BioRad). The standards were spun at 10000g for 10 min prior to loading onto a Superdex 200 16/60 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare). An elution of 80 mL was collected in 1 mL fractions at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min after the void volume (40 mL collected in 10 mL fractions) for a total elution volume of 120 mL. The peak heights (monitored by absorbance at 280 nm) were determined and their retention time (elution volume) was plotted against the log10 of the molecular weight of the standards. The points were fit to a line and this standard curve was used to determine the size of proteins eluting from the RFC4GAT samples. The RFC4GAT samples were centrifuged at 10000g for 10 min and eluted from columns equilibrated in two different storage buffers: (1) standard RFC storage buffer and (2) RFC storage buffer plus 0.75 M maltose. The elution method was the same for each sample as for the standards. Protein peaks were assayed by 12% SDS–PAGE analysis.

Kd determination in equilibrium PCNA opening assays

All steady-state measurements were made on a QuantaMaster QM1 spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International) at room temperature using a quartz cuvette with a 3 × 3 mm light path (Hellma 105.251-QS). AF488 was excited at 495 nm and emission was measured using a 3 nm bandpass. To generate each point, emission spectra were recorded after reagents were sequentially added to the cuvette. First, assay buffer with 0.5 mM ATP (where present) was added for a background signal, then 10 nM PCNA-AF488 for unbound PCNA, and then RFC, from 0 to 400 nM, was added to measure the signal for bound PCNA. Storage buffer was added instead of RFC to generate the 0 nM RFC point. After correcting for buffer background the intensity of bound PCNA was divided by the intensity for free PCNA for each point. Each value at 517 nm was then divided by that obtained for 0 nM RFC, setting this point to 1, to account for the change in fluorescence due to dilution. All other points are relative to this value. Three independent experiments were done and Kd values for each were calculated using Eq. (1), where PCNA is the total concentration of PCNA, RFC is the total concentration of RFC, Imax is the maximum intensity, and Imin is the minimum intensity:

| (1) |

The average value and standard error for three independent calculations are reported and the average relative intensities versus RFC concentration and standard errors were graphed and fit using Kaleidagraph [13-15,17].

Kd determination in equilibrium PCNA binding assays

Data were collected and analyzed as for PCNA opening except that MDCC was excited at 420 nm, emission was measured at 467 nm using a 4 nm bandpass, and data collected without ATP were titrated to 2.56 μM RFC. The average value and standard error for three independent calculations are reported and the average relative intensities and standard errors were graphed and fit using Kaleidagraph [13-15,17].

Kd determination in equilibrium DNA binding assays

Steady-state anisotropy measurements were made on a QuantaMaster QM1 spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International) with polarizers at room temperature using a quartz cuvette with a 3 × 3 mm light path (Hellma 105.251-QS). Samples were excited with vertically and horizontally polarized light using a 9 nm bandpass and both horizontal and vertical emissions were monitored at 605 nm for 30 s and the average value was calculated. Anisotropy values were calculated using a G factor, to account for polarization bias (Eq. (2)), determined under the same experimental conditions:

| (2) |

To generate each point, polarized emissions were recorded after reagents were sequentially added to the cuvette. First, assay buffer with 0.5 mM ATPγS was added for background signal, then 25 nM DNA-RhX for the free DNA signal, then RFC (from 0 to 1 μM without maltose and 0–1.5 μM with maltose) for the RFC▪DNA bound signal, and then PCNA (1 μM without maltose and 1.5 μM with maltose) for the RFC▪PCNA▪DNA bound signal. Anisotropy values were calculated for RFC▪DNA and RFC▪PCNA▪DNA using Eq. (3) where IVV and IVH are vertical and horizontal intensities, respectively, when excited with vertically polarized light:

| (3) |

Three independent experiments were done and Kd values for each were calculated using Eq. (4), where DNA is the total concentration of DNA, RFC is the total concentration of RFC, Imax is the maximum intensity, and Imin is the minimum intensity:

| (4) |

The average value and standard error for three independent calculations are reported and the average anisotropy values versus RFC concentration and standard errors were graphed and fit using Kaleidagraph [14,17].

Pre-steady state opening assays

Assays were done using a BioLogic SF400 stopped-flow apparatus at 20 °C. Single-mix reactions were performed by mixing equal volumes (75 μL) of a solution of RFC and 0.5 mM ATP and a solution of PCNA-AF488 and 0.5 mM ATP immediately before they entered the cuvette. Data were collected for a total of 1.6 s at 0.2 ms intervals and six or more individual kinetic traces were averaged. The time courses were corrected for background by subtracting the signal for buffer. AF488 emission fluorescence was monitored using a 515 nm cut-on filter while exciting at 495 nm. The corrected time courses were normalized to 1 and fit to a single exponential rise (Eq. (5)) using Kaleidagraph [13-15,17]:

| (5) |

Final concentrations for each experiment were: 20 nM PCNA-AF488, 0.5 mM ATP, and 20, 40, and 80 nM RFC.

Results

Gel filtration analysis

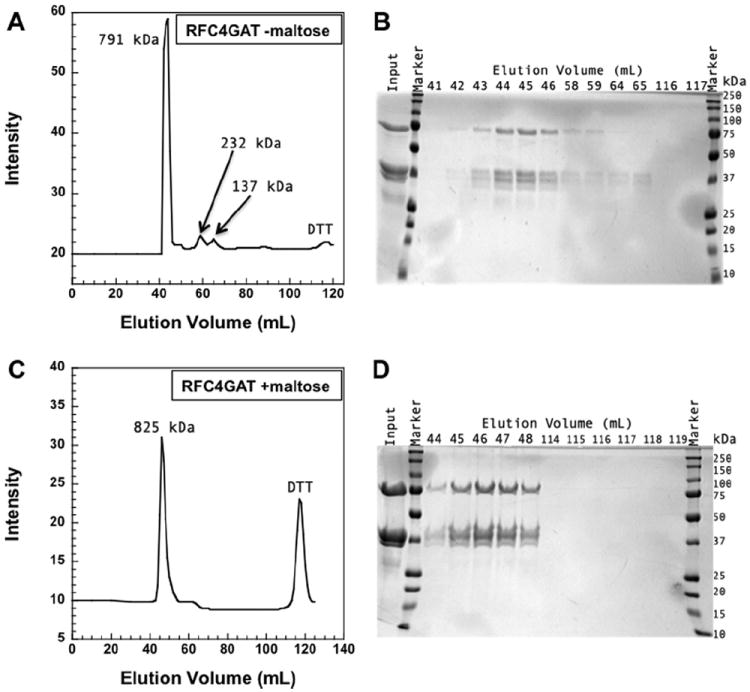

It has been shown previously that the S. cerevisiae clamp loader replication factor C (RFC), and particularly complexes harboring Walker A mutations, have decreased stability, in part due to protein aggregation [12,21]. Though Gomes et al. showed that the addition of 0.05% broad range ampholytes (pH 3.5–9) increased RFC solubility, this additive was not effective at concentrations and under conditions used in our assays. Sodium chloride at a concentration of 300 mM increases the solubility of wt RFC when stored at high concentrations, but is not effective for storage of Walker A mutants. A variety of buffer additives were tested based upon those used for other proteins in the literature [22], and addition of 750 mM maltose to RFC storage buffer prevented the Walker A mutants from precipitating. To more analytically (and quantitatively) measure the effects of 750 mM maltose on the solubility of RFC, the Walker A mutant harboring a mutation in the RFC4 subunit (RFC4GAT), was analyzed by gel filtration chromatography using Superdex 200 resin. One RFC4GAT sample had been stored in RFC storage buffer (30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 300 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol) and the other in RFC storage buffer with 750 mM maltose (30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 750 mM maltose). The RFC4GAT sample stored only in RFC storage buffer contained visible precipitation upon thawing from −80 to 4 °C. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min prior to loading the sample onto the column. The chromatogram (Fig. 2a) and accompanying SDS–PAGE analysis (Fig. 2b) show that there are multiple protein complexes in this sample, some of which do not contain all five subunits of RFC, suggesting that the complex may be falling apart when stored in this buffer. Based upon standards, the molecular weights of the proteins in each peak are 791, 232, and 137 kDa for elution volumes of 41–46, 58–59, and 64–65 mL, respectively. The RFC4GAT sample stored in RFC storage buffer with 750 mM maltose did not have visible precipitant upon thawing. Additionally, the chromatogram (Fig. 2c) and SDS–PAGE analysis (Fig. 2d) show that there is only one population of RFC4GAT, indicating that the complex is stable in this buffer. The single peak at 44–48 mL elution volume corresponds to a protein molecular weight of 825 kDa. Though the calculated molecular weight of the RFC4GAT complex is higher than the reported molecular weight of RFC of 220 kDa [19], wt RFC also elutes at this higher molecular weight (data not shown). The peak at 116–117 mL in each experiment elutes at the solvent front and was found to have a maximum absorbance of 283 nm. This is likely due to oxidized DTT [23], which is present in both protein storage buffers.

Fig. 2.

RFC4GAT size exclusion chromatography. The molecular weight of RFC is 220 kDa, with each subunit as follows: Rfc1 65 kDa, Rfc2 40 kDa, Rfc3 38 kDa, Rfc4 36 kDa, and Rfc5 40 kDa. (A) An elution profile from Superdex 200 of RFC4GAT (1.6 mg) is shown. The complex was stored in 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol at −80 °C. Intensities (absorbance at 280 nm) are plotted as a function of elution volume and are an arbitrary scale. (B) SDS–PAGE (12%) analysis of fractions from the elution in panel A is shown. Lanes are labeled by elution volume (mL) and the input lane is the sample loaded onto the column. (C) An elution profile from Superdex 200 of RFC4GAT (2.2 mg) that was stored in 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and 750 mM maltose at −80 °C is shown. Intensities (absorbance at 280 nm) are plotted as a function of elution volume and are an arbitrary scale. (D) SDS–PAGE (12%) analysis of fractions from the elution in panel C is shown. Lanes are labeled by elution volume (mL) and the input lane is the sample loaded onto the column.

Equilibrium PCNA opening

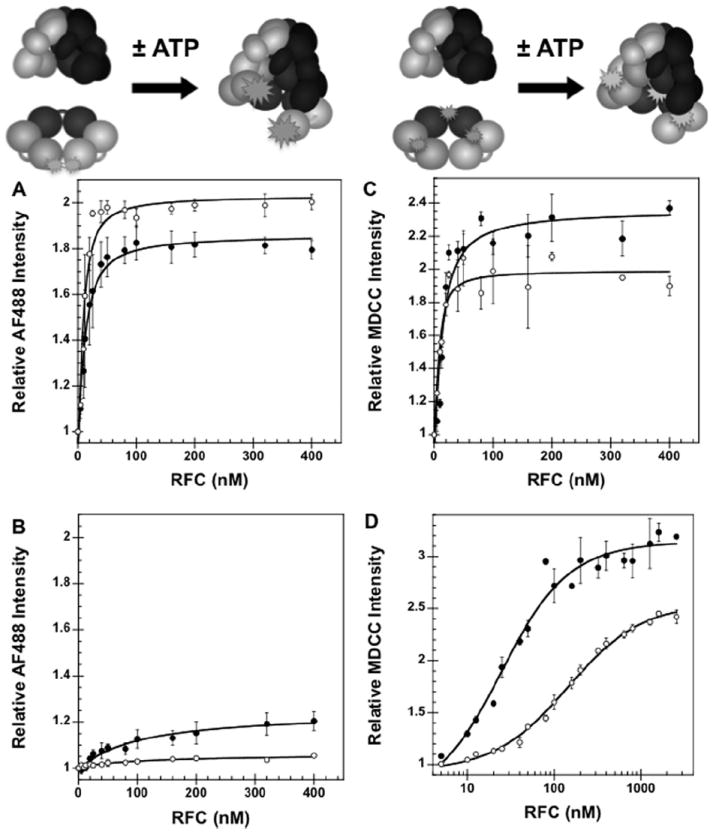

PCNA labeled with AlexaFluor 488 (AF488) was prepared as previously described [13,15]. The labeled residues (Cys-111 and Cys-181) are located on the interface between two monomers and are approximately 5 Å apart. When PCNA is closed, the AF488 fluorescence is quenched. When PCNA is open, the quench is relieved and an increase in fluorescence is observed (cartoon Fig. 3a), indicative of a greater population of open clamps. This assay takes advantage of the property that two fluorophores in close proximity will self-quench [13-15,17]. This opening assay was used to determine whether addition of maltose to the buffer affects the interactions between RFC and PCNA under equilibrium conditions. The relative AF488 fluorescence intensity is plotted against RFC concentration (Fig. 3a). Dissociation constants, Kd values, of 9.8 ± 4.2 and 4.4 ± 1.5 nM, were calculated from the data for assays without (filled circles) and with (open circles) maltose, respectively, using Eq. (1). The Kd values are within experimental error of one another, and the fold-change in intensity observed for each ATP-dependent reaction is similar, indicating that the presence of maltose in assay buffer does not affect the AF488 response used to monitor PCNA opening in the ATP-dependent reactions. Under both conditions, little opening was observed in the absence of ATP (Fig. 3b) when compared to the ATP-dependent reactions. However, the small amount of opening in the absence of ATP, about 20% of the total change in intensity for ATP-dependent opening (Fig. 3b, filled circles), is reduced to almost nothing in the presence of maltose (Fig. 3b, open circles). This suggests that the addition of maltose reduces weak, ATP-independent interactions between RFC and PCNA.

Fig. 3.

Equilibrium PCNA opening and binding assays in the presence and absence of 750 mM maltose. (A) Equilibrium binding of PCNA by RFC was determined by measuring the intensity of AF488 as a function of RFC concentration in the presence of ATP and presence (open circles) and absence (filled circles) of maltose. AF488 fluorescence is quenched in the absence of RFC. RFC binding in the presence of ATP relieves the quench at one interface, giving in increase in AF488 fluorescence. (B) Equilibrium binding of PCNA by RFC was determined by measuring the intensity of AF488 as a function of RFC concentration in the absence of ATP and presence (open circles) and absence (filled circles) of maltose. (C) PCNA binding assay with wt RFC in the presence of ATP and presence (open circles) and absence (filled circles) of maltose. Equilibrium binding of PCNA by RFC was determined by measuring the intensity of MDCC as a function of RFC concentration. MDCC fluorescence increases upon the binding of RFC to PCNA. (D) Equilibrium binding of PCNA by RFC was determined by measuring the intensity of MDCC as a function of RFC concentration in the absence of ATP and presence (open circles) and absence (filled circles) of maltose. The relative intensity of AF488 at 517 nm ((A) and (B)) or MDCC at 467 nm ((C) and (D)) is plotted as a function of RFC concentration. Data were fit to Eq. (1) (Materials and methods) using Kaleidagraph [13-15,17] to obtain Kd values and are the average of three independent experiments. PCNA-AF488 or PCNA-MDCC and RFC were added sequentially to a solution of assay buffer and ATP (when present). Final reaction conditions: 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 8 mM MgCl2, 0.5% glycerol, 750 mM maltose (when present), 0.5 mM ATP (when present), 10 nM PCNA-AF488 or 10 nM PCNA-MDCC, and 0–2.56 μM RFC.

Equilibrium PCNA binding

A fluorescence intensity-based assay in which PCNA was labeled with N-(2-(1-maleimidyl)ethyl)-7-(diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxamide (MDCC) was used to measure RFC binding to PCNA (M. Marzahn, in preparation). The labeled residue (Cys-43) is located on the PCNA surface where RFC makes contacts upon binding. When RFC binds to PCNA an increase in fluorescence is observed (cartoon Fig. 3c), indicative of a greater population of bound clamps. This assay takes advantage of the property that this fluorophore is environmentally sensitive. This PCNA mutant was used to measure the dissociation constant, Kd, of binding for wt RFC under equilibrium conditions both in the presence (open circles) and absence (filled circles) of 750 mM maltose in assay buffer (Fig. 3c). The relative MDCC intensity is plotted against RFC concentration and fit to Eq. (1) to calculate Kd values of 8.5 ± 1.8 and 3.2 ± 0.74 nM, in the absence and presence of maltose, respectively. These values and the fold-change in intensity observed for each are similar, indicating that the presence of maltose in assay buffer does not affect the binding interaction or the MDCC response used to monitor PCNA binding. The effect of maltose on binding of RFC to PCNA was measured in the absence of ATP (Fig. 3d). Kd values of 25 ± 1.0 nM (filled circles) and 150 ± 12 nM (open circles) were obtained in the absence and presence of maltose, respectively. The increase in intensity is higher in assays without ATP than with ATP, suggesting that RFC likely makes different interactions with PCNA in the absence of ATP. As was seen with the PCNA opening assay, the addition of maltose appears to decrease weak, ATP-independent interactions between RFC and PCNA. At 400 nM RFC in the absence of maltose, at least 75% of PCNA-MDCC is bound by RFC (Fig. 3d), whereas at this same concentration, less than 20% of the PCNA is opened (Fig. 3b, filled circles). This shows that the defect in PCNA opening in the absence of ATP and presence of maltose is not simply due to weaker RFC▪PCNA binding.

Equilibrium DNA binding

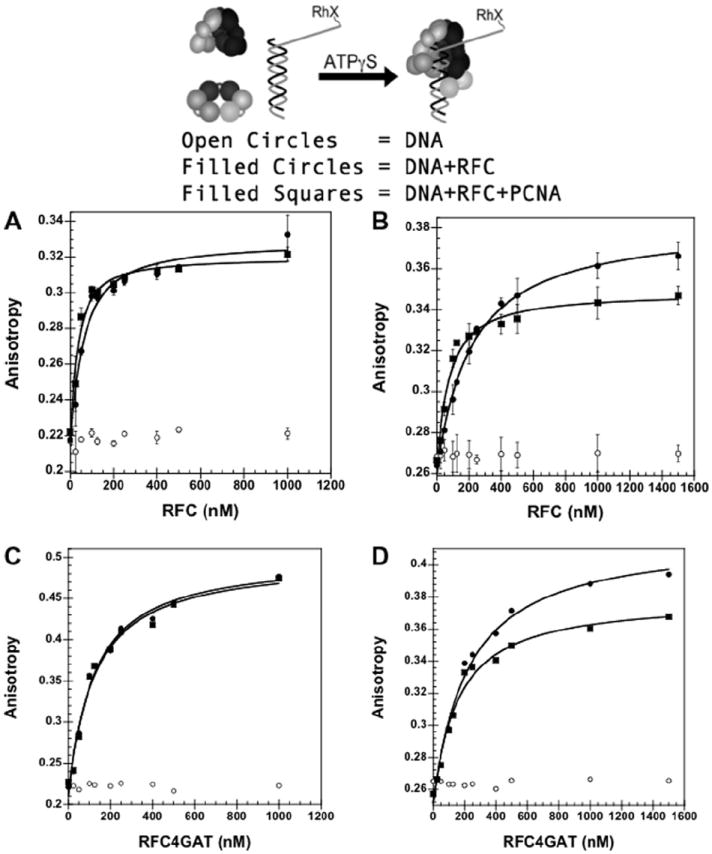

A fluorescence anisotropy-based assay was used to measure DNA binding by RFC [16-18]. A DNA duplex, consisting of a 30-mer primer annealed to a 60-mer template, was labeled at the 5′ end with X-rhodamine (RhX). The rotation of the fluorophore was quantified by measuring polarized emission when exciting with polarized light. This assay measures DNA binding by monitoring a change in anisotropy, or rotational motion, of the fluorophore. An increase in anisotropy, indicating a decrease in rotational motion, is observed upon RFC binding to the DNA duplex. This DNA-RhX duplex was used to measure the wt RFC▪DNA dissociation constant (Kd) under equilibrium conditions in the presence and absence of 750 mM maltose in assay buffer (cartoon Fig. 4). The assay utilized ATPγS instead of ATP to prevent ATP hydrolysis and subsequent DNA release. In each graph, the anisotropy values for free DNA (open circles), DNA + RFC (closed circles), and DNA + RFC + PCNA (squares) are plotted against RFC concentration and fit to Eq. (4) to calculate Kd values. Without maltose, Kd values of 47 ± 10 nM (wt RFC) and 23 ± 9 nM (wt RFC + PCNA) were obtained (Fig. 4a). With maltose, Kd values of 200 ± 31 nM (wt RFC) and 65 ± 24 nM (wt RFC + PCNA) were obtained (Fig. 4b). A similar increase in anisotropy (about 0.1 units) was observed with and without maltose. Additionally, stimulation of RFC▪DNA binding by PCNA was observed in both assays. Maltose increases the viscosity of the solution and decreases the observed rotational motion of RhX as indicated by the increase in the anisotropy of DNA-RhX from about 0.22 in the absence of maltose to about 0.26 in the presence of maltose. In the absence of maltose, anisotropy values greater than the theoretical maximum of 0.4 were measured in titrations of DNA-RhX with RFC4GAT. Scattered light due to protein precipitation in the assays is the likely cause of these erroneous values (Fig. 4c). With the addition of maltose the anisotropy values for RFC4GAT drop below 0.4 (Fig. 4d). These data indicate that without maltose, the mutant protein complex has a higher tendency to precipitate in solution.

Fig. 4.

Equilibrium DNA binding assay in the presence and absence of 750 mM maltose. DNA-RhX fluorescence anisotropy is plotted. The anisotropy increases upon binding by RFC or RFC▪PCNA. (A) wt RFC▪DNA binding in the absence of maltose. (B) wt RFC▪DNA binding in the presence of maltose. (C) RFC4GAT▪DNA binding in the absence of maltose. (D) RFC4GAT▪DNA binding in the presence of maltose. The anisotropy of RhX at 605 nm is plotted as a function of RFC concentration for free DNA (open circles), RFC + DNA (filled circles) and RFC + PCNA + DNA (squares). Data were fit to Eq. (4) (Materials and methods) using Kaleidagraph [14,17] to obtain Kd values and are the average of three independent experiments for (B) and (C). Data in (D) and (E) are single experiments. DNA-RhX, RFC, and PCNA were added sequentially to a solution of assay buffer and ATPγS. Final reaction conditions: 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 8 mM MgCl2, 0.5% glycerol, 0.5 mM ATPγS, 1 μM PCNA (without maltose) or 1.5 μM PCNA (with maltose), and 0–1 μM RFC (without maltose) or 0–1.5 μM RFC (with maltose).

Pre-steady state PCNA opening

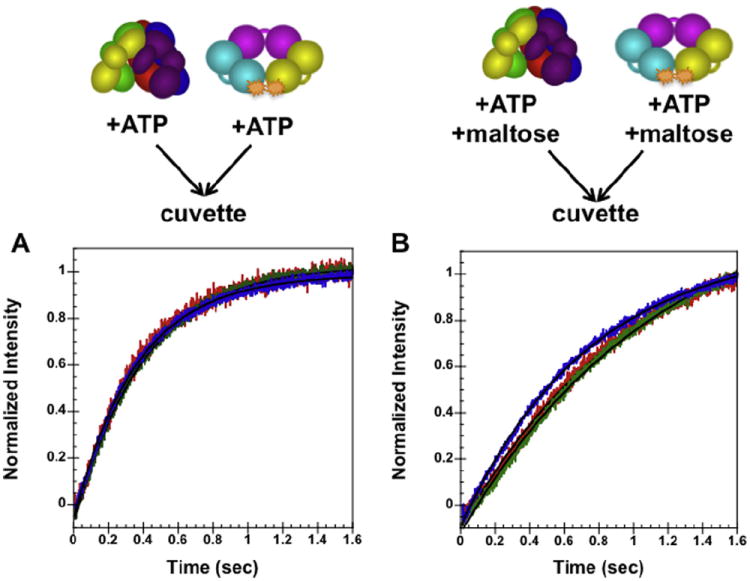

The PCNA mutant labeled with AF488 (described above) was used to monitor PCNA opening by wt RFC in real-time. A solution of RFC with ATP (±750 mM maltose) was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with a solution of PCNA-AF488 with ATP (±750 mM maltose). The increase in AF488 fluorescence was monitored over time. The normalized intensity was plotted against time and the resulting data were fit to Eq. (5) to determine the rate of PCNA opening. Without maltose (Fig. 5a) an apparent opening rate of 2.7 ± 0.1 s−1 was obtained. With maltose (Fig. 5b) an apparent opening rate of 1.1 ± 0.1 s−1 was obtained. Previous work [13] has shown that this rate reflects the rate of clamp opening and not the rate of RFC · PCNA binding. The rate of opening is about two times slower in the presence of maltose suggesting that the addition of maltose gives a small decrease in the rate of this intramolecular reaction. No adverse effects (such as incorrect volume dispensing or presence of air bubbles) due to the increased viscosity of assay buffer with the addition of 750 mM maltose were observed during these experiments.

Fig. 5.

Pre-steady state opening in the absence, (A), and presence, (B), of maltose. The normalized change in AF488 intensity is plotted as a function of time. Data were fit to Eq. (5) (Materials and methods) using Kaleidagraph [13-15,17] to obtain kobs rates of opening. The solid black lines through the time courses are the result of an empirical fit of the data to a single exponential. PCNA-AF488 and RFC in assay buffer with ATP were mixed in a 1:1 ratio for a final reaction volume of 150 μL. Final reaction conditions: 30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 8 mM MgCl2, 4% glycerol, 750 mM maltose (where present), 0.5 mM ATP, 20 nM PCNA-AF488, and 20 (red), 40 (green), and 80 nM (blue) RFC. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Discussion

Sliding clamps and clamp loaders are essential components of the replisome in all domains of life. An understanding of how these proteins interact with one another and with the DNA template can give insights into the complexity of cellular maintenance and potentially into how cancers may arise when this machinery is disrupted. Protein solubility can be problematic when attempting to purify protein complexes in the milligram amounts needed for biochemical and biophysical assays and when measuring enzymatic activity. Additionally, eukaryotic recombinant proteins tend to be less soluble than their prokaryotic counterparts. In this work, conditions for producing S. cerevisiae RFC clamp loader complexes harboring Walker A mutations are identified and this buffer additive is used under equilibrium conditions and in the pre-steady state to determine whether it has an effect on the fluorescence-based assays we use to study protein▪protein and protein▪DNA interactions.

Initial studies found that while we obtained high yields of protein from expression (generally more than 5 mg of wt RFC protein per liter of media) wt RFC was less soluble than its E. coli counterpart, γ complex. This was not an unexpected result as the eukaryotic replication proteins are less well-behaved than those from bacteria and RFC insolubility has been documented previously [21]. We were able to increase the concentration of sodium chloride in our storage buffer to solve this problem for wt RFC (Materials and methods). Surprisingly, the RFC complexes harboring the Walker A mutations, a single point mutation of Lys to Ala (Fig. 1b), were even less soluble than wt RFC. After utilizing a variety of buffer additives from many categories [22], including kosmotropes, chaotropes, amino acids, detergents, and sugars (summary of additives tested given in Table 1), we found that the addition of 750 mM maltose to the storage buffer greatly increased solubility of these mutants. This equates to approximately 25.7% (w/v) maltose which gave us a twofold dilemma: (1) our fluorescence-based assays utilize fluorophores that are environmentally sensitive and addition of maltose at this concentration may have an environmental effect on fluorescence; and (2) this high concentration of maltose increases the viscosity of our assay buffer, potentially posing problems with our real-time assays, which are run on a stopped-flow apparatus. The data presented seek to verify that maltose is stabilizing the mutant RFC complexes and determine, using wt RFC as a control, whether the addition of maltose to assay buffer conditions has an effect on our fluorescence assays under equilibrium and pre-steady state conditions.

Table 1.

Summary of buffer additives tested to improve RFC Walker A mutant solubility.

| Buffer additive | Concentration | Improved protein solubility? | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salts (kosmotropes and chaotropes) | |||

| Ammonium chloride* | 138 mM | No | No improvement |

| Ammonium sulfate* | 50–250 mM | Yes | Improved solubility at 150 mM or higher, but at these concentrations the ionic strength is too high for DNA binding measurements |

| Calcium chloride* | 42.5–150 mM | Yes | Improved solubility at highest concentration but the ionic strength is too high for DNA binding measurements |

| Manganese chloride* | 150 mM | No | No improvement |

| Magnesium sulfate* | 32 mM | No | No improvement |

| Potassium chloride | 150 mM | No | No improvement |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 150 mM | No | No improvement |

| Sodium chloride* | 150–300 mM | Yes | Improved solubility at highest concentration, but the ionic strength is too high for DNA binding measurements |

| Sodium sulfate | 42.5 mM | No | No improvement |

| Amino Acids | |||

| Glycine | 150 mM | No | No improvement |

| L-arginine HCl* | 50–250 mM | Yes | Improved solubility at highest concentration, but the ionic strength is too high for DNA binding measurements |

| Detergents | |||

| Brij-35 | 20 μM | Yes | Moderate improvement |

| Nonidet P40 | 0.1% | n/a | Background fluorescence too high |

| Triton X-100 | 0.1% | n/a | Background fluorescence too high |

| Tween-20 | 0.1% | No | No improvement |

| Sugars and polyhedric alcohols | |||

| Glycerol | 0.5–10% | No | No improvement |

| Glucose | 50 mM | No | No improvement |

| Maltose | 50–750 mM | Yes | Increased solubility with increasing sugar concentration |

| Sucrose | 50–750 mM | Yes | Moderate improvement |

| Trehalose | 50–750 mM | Yes | Increased solubility with increasing sugar concentration |

Summary of buffer additives tested to improve RFC Walker A mutant solubility. Solubility was assayed by visual inspection and by monitoring anisotropic scattered light for solutions of 1 μM RFC4GAT in assay buffer supplemented with each additive. Additives that improved solubility were then used in DNA binding experiments to determine (1) whether there was any change in background fluorescence and (2) whether addition of the additive had an effect on DNA binding. Additives marked with an asterisk (*) showed improved solubility at the higher concentrations tested but not at the lower concentrations that maintained an ionic strength low enough to measure DNA binding. Additives that gave the most improvement in solubility, had no background fluorescence, and had minimal effects on DNA binding are shown in bold text. n/a = not assayed.

Gel filtration analysis of a complex with a mutation in the RFC4 subunit (RFC4GAT) stored in RFC storage buffer indicated that the complex is unstable and appears to be falling apart (Fig. 2a and 2b). Additionally, significant precipitation is visually observed in these samples upon thawing from storage at −80 to 4 °C working temperature. The majority of the precipitated protein was removed prior to running the size exclusion column and is not visible on the SDS–PAGE gel. However, based upon the presence of peaks with sub-complex protein sizes, we believe that the precipitation is due to the RFC complex falling apart. Based upon work by Bondos and Bicknell, a variety of buffer additives were used to determine whether any would help to stabilize the mutant RFC complexes [22]. A summary of the effects each additive had is given in Table 1. The addition of higher salt concentrations (sodium chloride and others) did stabilize the protein, but these concentrations would prevent any downstream DNA binding analyses. Several detergents also increased protein solubility but gave high fluorescence backgrounds that would be undesirable in our assays. Two sugars, maltose and trehalose, prevented protein precipitation and did not give any background fluorescence. All further studies were continued with maltose, as initial results did not show a difference between the two sugars and maltose is more economical. Gel filtration analysis of a sample stored with the addition of 750 mM maltose (Fig. 2c and 2d) verified that the complex was more stable, giving only a single peak on the chromatogram. This single peak, like wt RFC, elutes at a higher molecular weight than expected, but the protein no longer appears to fall apart. This high molecular weight peak, for wt RFC and RFC4GAT, could be caused by several factors: (1) protein interactions with the Superdex resin cause RFC to elute at a higher molecular weight than expected; (2) the RFC protein complex does not behave as an ideal, globular protein and runs anomalously at what appears to be a higher molecular weight complex; or (3) RFC forms stable, higher-order protein aggregates. Regardless, the addition of maltose to the RFC storage buffer prevents the mutant complexes from precipitating.

Having established that maltose stabilized the mutant RFC complexes, three fluorescence-based assays were used to determine whether the addition of maltose would affect protein▪protein or protein▪DNA interactions, and at a technical level whether maltose would have any effects on the assays themselves. For these experiments, wt RFC was used so that a comparison without maltose could be made. These assays were designed to measure three different ATP-dependent parameters under equilibrium conditions: PCNA binding (Fig. 3c), PCNA opening (Fig. 3a), and DNA binding (Fig. 4a and 4b). In each of the assays, the Kd values obtained and the fold-change in intensity observed are very similar. Additionally, the light scattering that was giving aberrant anisotropy values for RFC4GAT · DNA binding was eliminated with the addition of maltose to the assay buffer (Fig. 4c and 4d). These data show that the inclusion of maltose in assay buffer does not change the ATP-dependent interactions RFC makes with PCNA and DNA and does not have an effect on the fluorescence response of any of the fluorophores. However, the addition of maltose did have a significant effect on RFC · PCNA interactions in the absence of ATP. In both the PCNA opening (Fig. 3b) and PCNA binding (Fig. 3d) assays, a significant difference in the fold-change in intensity and the calculated Kd values was seen. In both assays, maltose appears to disrupt weak, possibly non-specific, ATP-independent interactions between RFC and PCNA. ATP-dependent Kd values for PCNA binding and opening are very similar to those obtained for the E. coli clamp loader, γ complex, and β clamp. The results from the maltose-independent binding were surprising since they indicated that RFC has a higher affinity for PCNA in the absence of ATP than the E. coli clamp loader for its clamp under similar conditions [14].

PCNA opening was also monitored in the pre-steady state using a stopped-flow apparatus (Materials and methods). A technical concern with using maltose in the stopped-flow experiments is that the solution may be too viscous, leading to inaccurate volume dispensing, incomplete mixing, and possibly introduce air bubbles in the cuvette. A PCNA opening assay was run with wt RFC both with and without maltose (Fig. 5). No artifacts indicative of incorrect volume dispensing or air bubbles were seen in the raw data (data not shown). The inclusion of maltose in the assay buffer did not have any effect on the ability to collect stopped-flow data. As seen previously, the opening rate was 1–2 s−1 and the rates were not concentration dependent, though the opening rate appears to be two times slower in the presence of maltose. This is likely due to the viscosity of the assay buffer and not to a disruption of the reaction since the Kd values for binding and opening remain constant in the steady-state (Fig. 3a and 3b). It is possible that in addition to preventing protein precipitation, maltose “coats” the proteins in such a way that intramolecular, or conformational, changes within RFC itself are affected.

Conclusions

While maltose does not prevent protein aggregation, also seen with wt RFC, the addition of maltose to the final storage buffer and assay buffer increases the solubility of RFC complexes with mutations in the Walker A motif, most likely preventing complexes from falling apart. Overall, maltose does not appear to have any effect on the collection of data or the kinetic constants determined from ATP-dependent equilibrium or pre-steady state analysis using fluorescence-based assays. The addition of maltose to ATP-independent equilibrium opening and binding assays appears to disrupt weak, ATP-independent interactions between RFC and PCNA. Additionally, the viscosity of solutions in pre-steady state analysis produces slightly slower reactions, necessitating that mutant RFC complexes be assayed alongside wt RFC using identical reaction conditions to make accurate comparisons of mutant RFC activity. Future studies will utilize these conditions to characterize the mutant complexes and determine the role these residues play within the clamp loading reaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mike O’Donnell (Rockefeller University) for plasmids used to express recombinant proteins.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM082849 to L.B.B.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: RFC, replication factor C; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; DTT, dithiothreitol; MgCl2, magnesium chloride; RhX, X-rhodamine; DNA-RhX, DNA labeled with X-rhodamine; RFC4GAT, RFC with mutation of the Rfc4 Walker A Lys to Ala; AF488, Alexa Fluor 488; PCNA-AF488, PCNA labeled with Alexa Fluor 488; MDCC, N-(2-(1-maleimidyl)ethyl)-7-(diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxamide; PCNA-MDCC, PCNA labeled with MDCC; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; Kd, dissociation constant.

References

- 1.Bloom LB. Loading clamps for DNA replication and repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Donnell M. Replisome architecture and dynamics in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10653–10656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J, Kong XP, Stukenberg PT, Onrust R. The sliding clamp of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme encircles DNA. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:953–957. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.9.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao N, Coryell L, Zhang D, Georgescu RE, Finkelstein J, Coman MM, et al. Replication factor C clamp loader subunit arrangement within the circular pentamer and its attachment points to proliferating cell nuclear antigen. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50744–50753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman GD, O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Structural analysis of a eukaryotic sliding DNA clamp–clamp loader complex. Nature. 2004;429:724–730. doi: 10.1038/nature02585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Levin MK, Sakato M, Zhou Y, Hingorani MM. Mechanism of ATP-driven PCNA clamp loading by S cerevisiae RFC. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White SR, Lauring B. AAA + ATPases: achieving diversity of function with conserved machinery. Traffic. 2007;8:1657–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majka J, Burgers PMJ. The PCNA-RFC families of DNA clamps and clamp loaders. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2004;78:227–260. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)78006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomes XV, Schmidt SL, Burgers PM. ATP utilization by yeast replication factor C. II. Multiple stepwise ATP binding events are required to load proliferating cell nuclear antigen onto primed DNA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34776–34783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Wigley DB. The “glutamate switch” provides a link between ATPase activity and ligand binding in AAA + proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson A, Yao NY, Bowman GD, Kuriyan J, O’Donnell M. The replication factor C clamp loader requires arginine finger sensors to drive DNA binding and proliferating cell nuclear antigen loading. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35531–35543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt SL, Gomes XV, Burgers PM. ATP utilization by yeast replication factor C. III. The ATP-binding domains of Rfc2, Rfc3, and Rfc4 are essential for DNA recognition and clamp loading. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34784–34791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson JA, Marzahn MR, O’Donnell M, Bloom LB. Replication factor C is a more effective proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) opener than the checkpoint clamp loader, Rad24-RFC. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2203–2209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.318899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson JA, Paschall CO, O’Donnell M, Bloom LB. A slow ATP-induced conformational change limits the rate of DNA binding but not the rate of beta clamp binding by the Escherichia coli gamma complex clamp loader. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32147–32157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paschall CO, Thompson JA, Marzahn MR, Chiraniya A, Hayner JN, O’Donnell M, et al. The Escherichia coli clamp loader can actively pry open the β-sliding clamp. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42704–42714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.268169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson SG, Williams CR, O’Donnell M, Bloom LB. A function for the psi subunit in loading the Escherichia coli DNA polymerase sliding clamp. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7035–7045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson SG, Thompson JA, Paschall CO, O’Donnell M, Bloom LB. Temporal correlation of dna binding, ATP hydrolysis, and clamp release in the clamp loading reaction catalyzed by the Escherichia coli γ complex. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8516–8527. doi: 10.1021/bi900912a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloom LB, Turner J, Kelman Z, Beechem JM, O’Donnell M, Goodman MF. Dynamics of loading the beta sliding clamp of DNA polymerase III onto DNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30699–30708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkelstein J, Antony E, Hingorani MM, O’Donnell M. Overproduction and analysis of eukaryotic multiprotein complexes in Escherichia coli using a dualvector strategy. Anal Biochem. 2003;319:78–87. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayyagari R, Impellizzeri KJ, Yoder BL, Gary SL, Burgers PM. A mutational analysis of the yeast proliferating cell nuclear antigen indicates distinct roles in DNA replication and DNA repair. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4420–4429. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomes XV, Gary SL, Burgers PM. Overproduction in Escherichia coli and characterization of yeast replication factor C lacking the ligase homology domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14541–14549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bondos SE, Bicknell A. Detection and prevention of protein aggregation before, during, and after purification. Anal Biochem. 2003;316:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleland WW. Dithiothreitol, a new protective reagent for SH groups. Biochemistry. 1964;3:480–482. doi: 10.1021/bi00892a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]