Background: Intestinal expression of guanylyl cyclase C (GC-C) modulates ion secretion, fluid transport, and epithelial cell proliferation.

Results: Site-specific glycosylation of GC-C regulates ligand binding, ligand-mediated activation, and interaction with the chaperone VIP36.

Conclusion: Glycosylation is an important mediator of GC-C folding and function.

Significance: Conditions that alter glycosylation of GC-C could control its activity and function in a tissue and disease-dependent manner.

Keywords: Cyclic GMP (cGMP), Glycosylation, Guanylate Cyclase (Guanylyl Cyclase), Receptor Modification, Receptor Regulation, VIP36, Heat-stable Enterotoxin

Abstract

Guanylyl cyclase C (GC-C) is a multidomain, membrane-associated receptor guanylyl cyclase. GC-C is primarily expressed in the gastrointestinal tract, where it mediates fluid-ion homeostasis, intestinal inflammation, and cell proliferation in a cGMP-dependent manner, following activation by its ligands guanylin, uroguanylin, or the heat-stable enterotoxin peptide (ST). GC-C is also expressed in neurons, where it plays a role in satiation and attention deficiency/hyperactive behavior. GC-C is glycosylated in the extracellular domain, and differentially glycosylated forms that are resident in the endoplasmic reticulum (130 kDa) and the plasma membrane (145 kDa) bind the ST peptide with equal affinity. When glycosylation of human GC-C was prevented, either by pharmacological intervention or by mutation of all of the 10 predicted glycosylation sites, ST binding and surface localization was abolished. Systematic mutagenesis of each of the 10 sites of glycosylation in GC-C, either singly or in combination, identified two sites that were critical for ligand binding and two that regulated ST-mediated activation. We also show that GC-C is the first identified receptor client of the lectin chaperone vesicular integral membrane protein, VIP36. Interaction with VIP36 is dependent on glycosylation at the same sites that allow GC-C to fold and bind ligand. Because glycosylation of proteins is altered in many diseases and in a tissue-dependent manner, the activity and/or glycan-mediated interactions of GC-C may have a crucial role to play in its functions in different cell types.

Introduction

Diarrheal diseases are one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality the world over (1). An important causative agent for watery diarrhea in children and travelers to developing countries is the heat-stable enterotoxin (ST)2 peptide, which disrupts intestinal fluid and ion secretion, leading to secretory diarrhea (2). Guanylyl cyclase C is the receptor for the ST peptides and is a member of the membrane-associated receptor guanylyl cyclase family. The endogenous ligands for GC-C are the gastrointestinal hormones, guanylin and uroguanylin, which, on binding GC-C, lead to receptor activation and cGMP production (3, 4). Secretion of water into the intestinal lumen, which is necessary for the lubrication and breakdown of the bolus of food, is regulated by guanylin and uroguanylin (5). ST is a superagonist of GC-C, and the abnormally high levels of intracellular cGMP produced on ST binding to GC-C cause aberrant fluid-ion efflux, leading to diarrhea (6). It was noted some time ago that there appeared to be an inverse correlation between the incidence of colorectal cancer and secretory diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (7), leading to the hypothesis that GC-C could also act as an anti-proliferative agent in the intestine (8, 9). Studies on colorectal cell lines indicated that GC-C exerts a cytostatic effect on epithelial cells that is mediated by cGMP and involves the regulation of calcium ion influx via a cyclic nucleotide gated channel (10) as well as inhibition of Akt signaling (9).

GC-C knock-out mice appear to show normal functioning of the gastrointestinal tract but were refractory to ST-induced diarrhea (11). However, roles for neuronally expressed GC-C were evident in these knock-out mice, which demonstrated abnormal feeding behavior resulting in obesity (12), and attention deficiency and hyperactive behavior (13). Only recently, however, was the first human disease associated with a mutation in GC-C reported (14). Members of a Norwegian family presented with a dominantly inherited, fully penetrant syndrome of frequent diarrhea, caused by a heterozygous mutation in GUCY2C (14). We reported that the effect of the Ser840 mutation to an Ile in GC-C resulted in a hyper-responsive form of GC-C, whereby levels of cGMP produced by the mutant receptor on ligand binding were 6–10-fold higher than observed for the wild type receptor. These elevated levels of cGMP could have caused the frequent diarrhea that is seen in patients, but additional clinical features such as a heightened susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease revealed additional roles of GC-C in the intestine. A second study reported inactivating mutations of GC-C in a small Bedouin population where an amino acid substitution in the extracellular domain reduced cGMP production by ∼50%, and an insertion of a single base pair in the intracellular domain resulted in truncation of the receptor before the C-terminal guanylyl cyclase domain (15). These patients reported multiple disturbances, which led to meconium ileus, and blockage of the small intestine caused by thick mucoid stools, presumably as a result of inadequate fluid secretion via the GC-C signaling pathway. Interestingly, human data contrast with that seen in mice, where the GC-C knock-out mouse was normal in terms of gastrointestinal function.

These critical roles of GC-C in human disease warrant a detailed understanding of the mechanisms by which the activity of human GC-C is regulated. GC-C has an extracellular domain that is involved in ligand binding (5). A single transmembrane domain is followed by a pseudokinase domain with sequence similarity to protein kinases (16, 17). The C-terminal guanylyl cyclase domain is linked to the kinase homology domain by a linker region (18). We have shown that the kinase homology domain binds ATP and mutation of a critical lysine residue involved in interacting with the β-phosphate of ATP prevents ligand-mediated activation of GC-C (16). The linker region appears to adopt a helical structure and extensive mutational analysis demonstrated the critical requirement of the linker in repressing the guanylyl cyclase activity of the receptor in the absence of its ligands (18).

Proteins may also be regulated by post-translational modifications. In the case of GC-C, the activity of the guanylyl cyclase domain is down regulated by phosphorylation by c-src tyrosine kinase (19), and potentiated by phosphorylation by protein kinase C (20). In the current study, we focused our attention on the extracellular domain of GC-C and the role of glycosylation in mediating ligand binding and receptor activation. Differentially N-glycosylated forms of GC-C are seen in both intestinal cells (21) and on heterologous expression in HEK293 cells, with a high-mannose form localized to the endoplasmic reticulum and a higher molecular weight form with complex glycosylation localized to the plasma membrane (22). We have now identified sites for glycosylation in human GC-C that modulate ligand binding and ligand-mediated activation of GC-C. We also demonstrate that GC-C forms carbohydrate-mediated interactions with the lectin chaperone VIP36 (23), thus providing the first evidence for a plasma membrane-bound receptor serving as a client for VIP36.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Mutations in the Extracellular Domain of GC-C

Human GC-C cDNA (pBSKGC-C; Ref. 24) was used as template for the generation of mutations in the extracellular domain of GC-C using the single mutagenic oligonucleotide-based protocol described earlier (25). The sequences of the mutagenic primers and details of cloning strategies are available upon request, and all mutations were verified by sequencing (Macrogen) prior to use.

Expression and Purification of GST Fusion Proteins

The extracellular domain of GC-C (amino acid residues 21 to 435) was cloned into the pGEX6P1 vector (GE Healthcare) to generate the plasmid pGEX6P1GC-CECDWT and pGEX6P1GC-CECDΔ10N. The human VIP36 coding region from amino acid 45–322 was amplified by PCR from cDNA prepared from the T84 colorectal carcinoma cell line and cloned into pGEX6P3 to generate the plasmid pGEX6P3VIP36.GST or GST tagged proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) Endo− cells following induction with isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (500 μm). Induction was carried out at 16 °C for 20 h for the expression and purification of GST-GC-CWT-ECD and GST-GC-CΔ10N-ECD, and at 37 °C for 3 h for the expression and purification of GST-VIP36. Cells were lysed by sonication in lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5 at 4 °C), 1 mm DTT, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mm benzamidine, and 2 mm PMSF, followed by centrifugation at 30,000 × g. The supernatant was interacted with GSH beads (Bioline), and the matrix was washed with buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm DTT, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100, followed by washes with buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm DTT, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, and 10% glycerol and stored at 4 °C. For GST-VIP36, lysis and wash buffers without EDTA and supplemented with 5 mm CaCl2 were used. Purity of protein was checked by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining.

Heterologous Expression of Wild Type and Mutant GC-C

Wild type and mutant GC-C were expressed in HEK293T cells and membrane protein fractions were prepared as described previously (18). In some cases, monolayers of cells were treated with 20 μg/ml of tunicamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) 18-h post transfection, and membrane fractions were prepared from these cells 24-h post treatment. For enzymatic deglycosylation of GC-C post expression in HEK293T cells, membrane protein (40 μg) from cells expressing wild type GC-C was resuspended in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, containing protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). PNGase F (250 units; New England Biolabs) was added, and incubation was continued at 4 °C for 12 h. Treated or untreated membrane protein was then subjected to Western blot analysis using GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody (22).

In Vitro Guanylyl Cyclase Assays

Membrane fractions were incubated in assay buffer (60 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 500 μm isobutyl methyl xanthine, and an NTP regenerating system consisting of 7.5 mm creatine phosphate and 10 μg of creatine phosphokinase) in the presence of 500 μm MnGTP or 1 mm MgGTP, with free metal ion concentrations maintained at 10 mm. The concentrations of free metals and metal-GTP complexes in assays were calculated using MaxChelator. When MnGTP was used as a substrate, activity measured represents the full catalytic potential of the guanylyl cyclase domain in GC-C (18). When MgGTP was used as a substrate, the basal guanylyl cyclase activity was lower, and therefore, ligand-mediated activation could be readily detected (18). ST (10−7 m) was added to measure ligand-mediated cGMP production, with MgGTP as substrate. All assays were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The assay was terminated by the addition of 400 μl of 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.75, and boiling of the samples. After centrifugation, the supernatant was taken for cGMP radioimmunoassay as described earlier (26).

Receptor Binding Assays

An analog of ST, STY72F was iodinated using Na125I as described previously (26). Membrane protein (50 μg) was incubated in binding buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 4 mm MgCl2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and protease inhibitors) with ∼100,000 cpm of 125I-labeled STY72F for 1 h at 37 °C in the absence or presence of 10−7 m of unlabeled ST, in a total volume of 100 μl. For Scatchard analysis, membrane protein was incubated with varying concentrations (10−11–10−9 m) of 125I-labeled STY72F for 1 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, samples were filtered through GF/C filters (Whatman) and washed with 5 ml of chilled 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), containing 0.9% NaCl and 0.2% BSA. The filters were dried, and the associated radioactivity was measured using a gamma counter.

Measurement of Ligand-stimulated cGMP Production in HEK293T Cells

Ligand-stimulated guanylyl cyclase activity was measured in intact HEK293T cells expressing either wild type or mutant GC-C, 72 h post transfection. The cell monolayer was incubated in medium containing 500 μm isobutyl methyl xanthine for 30 min at 37 °C in a 5% humidified CO2 incubator. ST (10−7 m) was then added, and incubation was continued for another 15 min, following which the cells were lysed in 200 μl of 0.1 n HCl. Cyclic GMP produced was measured by radioimmunoassay as described previously (26). Monolayers of cells were lysed in hot SDS sample buffer and taken directly for Western blot analysis of GC-C to monitor expression of wild type and mutant receptor.

Surface Biotinylation of Cells

Cells were washed with PBS (pH 8.0) containing 1 mm CaCl2 and 0.5 mm MgCl2 (PBS-CM), and incubated in PBS-CM containing 500 μg/ml of a cell impermeable biotin analog (biotinamidohexanoic acid 3-sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 4 °C. Excess reagent was quenched by washing with PBS containing glycine (100 mm) three times for 10 min. Membrane fractions were prepared and solubilized in interaction buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, protease inhibitors, and 0.1% SDS) and interacted with streptavidin-agarose beads (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4 °C to separate the biotinylated proteins. The beads were then washed thrice with wash buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% SDS) and twice with wash buffer without detergent. Protein associated with the beads was analyzed by Western blotting using the GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody.

Co-immunoprecipitation of GC-C and VIP36

The plasmids pcDNA3.1VIP36 and pcDNA3.1VIP36Lec− harboring the full-length cDNA of wild type human N-terminally Myc-tagged VIP36 or where the aspartic acid at position 131 was mutated to asparagine such that carbohydrate interaction was lost (VIP36lec−; Refs. 27 and 28) were a kind gift from Dr. K. Shirakabe (Center for Integrated Medical Research, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan). Myc-tagged VIP36 or Myc-tagged VIP36Lec− were expressed following transfection of pcDNA3.1VIP36 and pcDNA3.1VIP36Lec− plasmids into HEK293 cells which stably express GC-C (29), and 72 h post transfection, cell lysates were prepared in interaction buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors). The soluble fraction obtained after centrifugation at 13,000 × g was precleared with 2 μg/ml normal rabbit IgG and protein G Sepharose, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with IgG (2 μg/ml) prepared from a polyclonal antiserum raised to the C-terminal domain of GC-C (17). Protein G-agarose beads were used to isolate the immune-complex and were washed thrice with wash buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40), and twice with wash buffer without detergent, followed by Western blot analysis using the GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody or the anti-Myc monoclonal antibody, 9E10.

VIP36 Pulldown Assay

Membrane protein (400 μg) from HEK293T cells expressing either wild type or mutant GC-C was solubilized in lectin interaction buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, containing 5 mm CaCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, and protease inhibitors). Interaction was carried out at 4 °C for 4 h with 30 μl of GST-VIP36 bound to glutathione beads or an equivalent amount of GST bound to beads as a control, in the absence or presence of 20 mm mannose. Following interaction, beads were washed three times with wash buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, containing 1% Triton X-100, 5 mm CaCl2, and 150 mm NaCl) and twice with wash buffer without detergent. Protein associated with the beads was analyzed by Western blotting using the GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody.

RESULTS

Glycosylation Is Required for Folding and Transport of GC-C in Mammalian Cells

There are 10 Asn residues in the extracellular domain of GC-C that lie within a consensus site for glycosylation, but only 8 are predicted to be glycosylated (Table 1). We mutated all 10 Asn residues to Ala to abolish glycosylation (GC-CΔ10N). We expressed wild type or mutant receptor in HEK293T cells, in the absence or presence of tunicamycin, to pharmacologically inhibit glycosylation. GC-CΔ10N or wild type GC-C expressed in tunicamycin-treated cells migrated at a size of ∼120 kDa (Fig. 1A), indicating that all sites of N-linked glycosylation had been removed on mutation of the 10 Asn residues.

TABLE 1.

Predicted sites of N-linked glycosylation in GC-C

The sequence of the extracellular domain of GC-C was analyzed by NetNGlycan (version 1.0), where artificial neural networks, trained with regard to the sequence surrounding glycosylation sites, predict which sites can be glycosylated (+) or not (−).The number of - or + signs represent the confidence of the prediction.

| Amino acid position | Sequence | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 32 | NGSY | ++ |

| 75 | NVTV | +++ |

| 79 | NATF | + |

| 195 | NGTE | + |

| 284 | NVTA | +++ |

| 307 | NSSF | + |

| 313 | NLSP | --- |

| 345 | NITT | + |

| 357 | NLTF | - |

| 402 | NKTY | ++ |

FIGURE 1.

Effect of glycosylation on GC-C activity. A, monolayers of HEK293T cells were transfected with wild type GC-C or GC-CΔ10N and 18 h post-transfection and treated with 20 μg/ml of tunicamycin as indicated for 24 h. Western blot analysis of membrane protein (40 μg) was performed using GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody. B, receptor binding analysis was carried out using membrane protein (40 μg) as described in the text. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed twice with duplicate determinations. C, in vitro guanylyl cyclase assays using MnGTP as substrate was performed with membrane protein (5 μg) from cells expressing the wild type or GC-CΔ10N receptors, untreated or treated with tunicamycin. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed thrice with duplicate determinations. D, receptor binding assays and Scatchard analyses was performed using equivalent amounts of GST-tagged wild type or GC-CΔ10N ECDs bound to glutathione beads, purified from E. coli. Experiments were performed three times, and values represent the mean ± S.E. across the experiments. E, membrane protein (40 μg) from cells expressing GC-C were subjected to deglycosylation using PNGase F, followed by Western blot analysis with GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody. F, in vitro ST-mediated cGMP production was measured in control or deglycosylated membrane protein (10 μg) with MgGTP as substrate. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed thrice, with duplicate determinations. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Student's t test. *, p < 0.001; ns, not significant in comparison with the wild type receptor.

Membranes were prepared from transfected cells, and binding of radiolabeled ST was measured. As seen in Fig. 1B, neither wild type receptor present in cells treated with tunicamycin or GC-CΔ10N receptor was able to bind ligand. Ligand-independent guanylyl cyclase activity of the GC-CΔ10N receptor in the presence of MnGTP as substrate was comparable with that seen for the wild type receptor (Fig. 1C). This indicated that no gross misfolding of the intracellular domain of the receptor had occurred and that glycosylation of GC-C was important for folding of the extracellular domain of the receptor.

Eukaryotic proteins expressed in bacteria are non-glycosylated but in some cases have been found to be as functionally competent as their glycosylated counterparts expressed in eukaryotic cells (30, 31). The extracellular domain of GC-C expressed in E. coli has been shown to bind ST with an affinity equal to the glycosylated form expressed in mammalian cells (32). To ensure that it was the lack of glycosylation and not mutation of 10 Asn residues to Ala that caused the loss of ST binding seen in GC-CΔ10N, we expressed and purified the extracellular domain of wild type and mutant GC-C (residues 23 to 433) from E. coli as GST fusion proteins (supplemental Fig. 1) and monitored ST binding. As seen in Fig. 1D, ST was able to bind with comparable affinity to equivalent amounts of the purified extracellular domain of GC-CΔ10N and wild type protein. Therefore, the absence of binding of ST to full-length GC-CΔ10N expressed in mammalian cells was due to the specific requirement for glycosylation to ensure correct folding of the extracellular domain during its transit to the cell membrane.

The necessity for glycosylation after GC-C was folded and transported to the cell surface was checked. Membranes from cells expressing wild type GC-C were treated with PNGase F and Western blot analysis indicated that deglycosylation was complete, as both the 130- and 145-kDa forms migrated at 120 kDa (Fig. 1E). ST binding to these treated membranes was similar to that seen with membranes expressing the native receptor (Kd, 127.8 ± 1 (no PNGase F); Kd, 126.6 ± 3 (with PNGase F); supplemental Fig. 2), indicating that enzymatic deglycosylation of GC-C following maturation did not compromise ligand interaction. Importantly, treatment of deglycosylated membranes with ST resulted in enhanced cGMP production (Fig. 1F), similar to that seen in the native receptor.

Thus, the addition of sugars on GC-C during its synthesis in mammalian cells modulates localized folding in the extracellular domain that allows regions of GC-C to adopt conformations that allow binding of ST. Once the mature conformation is reached, there appears to be no requirement for glycosylation to retain this native conformation. In bacteria, it appears that folding of the extracellular domain of GC-C can occur even in the absence of glycosylation.

Analysis of Single-site Glycosylation Mutants

We mutated each of the predicted glycosylation sites in GC-C individually to Ala. Western blot analysis indicated that all the mutants were expressed and had traversed the secretory pathway, as inferred from the presence of the higher glycosylated form in all mutant proteins (Fig. 2A). Glycosylation can slow the migration of proteins on gels. Mutations at Asn32, Asn75, Asn79, Asn195, Asn284, Asn307, and Asn345 showed an increased mobility of both the 145- and the 130-kDa-sized bands (Fig. 2A). This indicated that substantial glycosylation occurs at these sites in wild type GC-C, and loss of glycosylation following mutation resulted in a reduction in molecular weight of the mutant proteins. No change in mobility occurred with the GC-CΔN313, GC-CΔN357, and GC-CΔN402 mutants. Two of the sites (Asn313 and Asn357) were predicted not to be glycosylated (Table 1), which may explain the similar migration of GC-C containing mutations at these sites and wild type receptor (Fig. 2A). Asn402 was however predicted to be glycosylated (Table 1), but the ΔAsn402 mutant protein did not show any significant difference in migration in comparison with the wild type receptor.

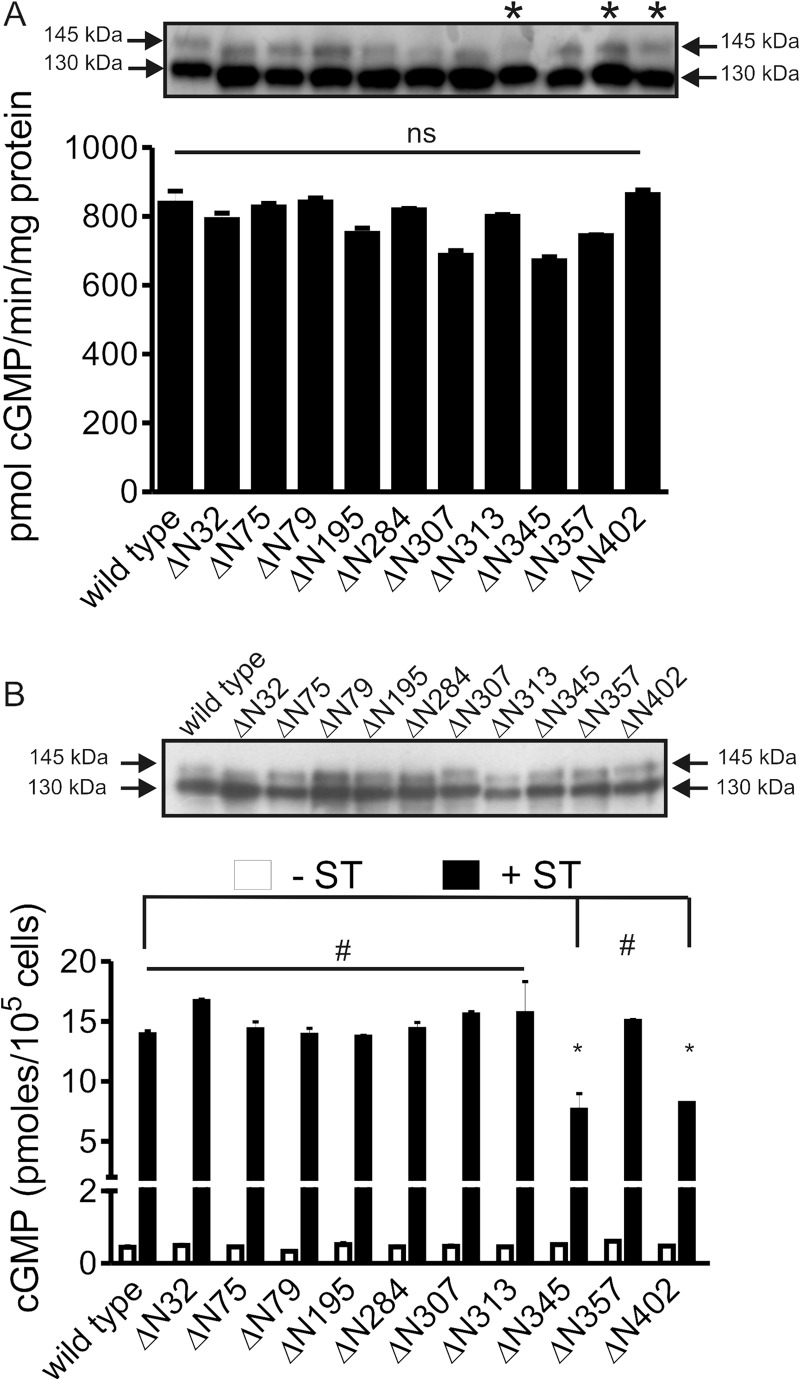

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of site-specific mutants of the 10 predicted glycosylation sites in GC-C. A, membrane protein (5 μg) from cells expressing the indicated GC-C mutants were assayed for guanylyl cyclase activity in the presence of MnGTP as substrate. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed twice with duplicate determinations. Inset, membrane protein (10 μg) from cells expressing the indicated mutants was analyzed by Western blotting using GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody. *, mutants that did not show a mobility shift. Data are representative of experiments performed three times. No significant (ns) difference was seen in guanylyl cyclase activity across experiments, when activity was normalized to the level of expression of the mutant proteins. B, ST (10−7 m) was applied to cultures of cells expressing wild type or the indicated mutant forms of GC-C and cGMP produced measured by radioimmunoassay. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative assay with duplicate determinations, and assays were repeated three times. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Student's t test. *, p < 0.01; #, p > 0.05 compared with wild type GC-C. Inset shows a Western blot of lysates prepared from transfected cells of a representative transfection.

Individual mutants showed similar in vitro guanylyl cyclase activity (measured in the presence of MnGTP) to that of the wild type receptor (Fig. 2A) and bound ST equally efficiently (supplemental Fig. 3). All mutants were tested for their ability to be stimulated by ST in intact cells (Fig. 2B). Except for the ΔAsn345 and ΔAsn402 mutant receptors, cGMP production was comparable with that seen for the wild type receptor.

Species and Site-specific Roles of Glycosylation in GC-C

Mutations of Asn195, Asn284, or Asn402 in porcine GC-C significantly reduced ligand-binding activity of the receptor (33). These sites are conserved in human GC-C, but in contrast to the results seen with porcine GC-C, none of the mutant receptors in human GC-C were compromised in ST binding (supplemental Fig. 3). However, the ΔAsn402 mutant receptor showed reduced responsiveness to ST (Fig. 2B).

Because Asn402 is present in the micro-domain involved in ST binding to porcine GC-C (34), the change of Asn to Ala may be poorly tolerated, resulting in lower production of cGMP. Alternatively, Asn402 may indeed be glycosylated but to a level insufficient to cause a dramatic shift in gel mobility. We therefore made a conservative mutation of the Asn to Gln (Fig. 3A), a residue that is not known to be glycosylated (35). Neither ST binding nor guanylyl cyclase activity in the presence of MnGTP was compromised in the N402Q mutant receptor (supplemental Fig. 5). However, ST-stimulated cGMP production was reduced both in intact cells (Fig. 3B) and in vitro (Fig. 3C). Thus, we can conclude that glycosylation does occur at Asn402, and although glycosylation at this site is not essential for ST binding, it appears to modulate the response of human GC-C to the ST peptide.

FIGURE 3.

Role of glycosylation at Asn402. A, Western blot analysis performed with wild type and indicated mutant receptors using the GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody. A representative blot is shown of experiments repeated three times. B, ST (10−7 m) was applied to cultures of cells expressing wild type or mutant forms of GC-C and cGMP produced measured by radioimmunoassay. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative assay with duplicate determinations, and assays were repeated three times. C, in vitro ST-mediated cGMP production was measured with membrane protein (10 μg) from cells expressing the indicated GC-C mutant using MgGTP as substrate. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed twice, with duplicate determinations. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Student's t test. *, p < 0.01.

Analysis of the Role of Glycosylation at Asn32, Asn75, Asn79, Asn195, Asn284, and Asn307

Asn357 is not predicted to be glycosylated (Table 1), and the ΔAsn357 mutant receptor did not show a mobility shift on electrophoresis (Fig. 2A) or any change in ST-stimulated cGMP production (Fig. 2B). Therefore, to elucidate the role of the additional six sites of glycosylation (Asn32, Asn75, Asn79, Asn195, Asn284, and Asn307), we generated the GC-CΔ6N mutant, leaving Asn residues at 313, 345, 357, and 402 unchanged. GC-CΔ6N migrated faster than wild type GC-C as a single band, (Fig. 4A). However, it migrated more slowly than the completely deglycosylated receptor (Fig. 1A), indicating that glycosylation had occurred at Asn345 and Asn402 residues. In vitro guanylyl cyclase assays carried out on membrane proteins expressing wild type GC-C or GC-CΔ6N, with MnGTP as substrate, indicated no change in the guanylyl cyclase activity of the mutant receptor (Fig. 4B). However, a marked reduction in ST-binding ability of the mutant receptor (Fig. 4C) was seen. Therefore, glycosylation at either all, or some of the six sites that were mutated in GC-CΔ6N was responsible for the folding of the extracellular domain of GC-C to allow efficient ST binding.

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of GC-C mutants deficient in binding ST. A, membrane protein (40 μg) from HEK293T cells expressing GC-CΔ6N was subjected to Western blot analysis using GCC:C8 monoclonal antibody. B, membrane proteins (5 μg) from cells expressing wild type or GC-CΔ6N were assayed for guanylyl cyclase activity in the presence of MnGTP. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed twice, with duplicate determinations. C, receptor binding analysis was carried out using membrane protein (40 μg) as described in the text. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed twice, with duplicate determinations. D, membrane protein (40 μg) from HEK293T cells expressing GC-CΔN75N79 was subjected to Western blot analysis using GCC:C8 monoclonal antibody. E. in vitro guanylyl cyclase activity was estimated in membrane proteins (5 μg) expressing wild type or GC-CΔN75N79 using MnGTP. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed twice with duplicate determinations. F, binding analysis was performed using membrane proteins from cells expressing either wild type GC-C or GC-CΔN75N79. Experiments were performed twice, and values represent the mean ± S.E. across experiments. G, in vitro ST-mediated cGMP production was measured in membrane proteins (10 μg) from cells expressing either wild type GC-C or GC-CΔN75N79, using MgGTP as substrate. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Student's t test. *, p < 0.01; ns, not significant compared with wild type GC-C.

Studies indicate that glycosylation sites proximal to the N terminus are important for the correct folding of proteins (36–38). However, proteins containing individual mutations of residues Asn32, Asn75, or Asn79 responded equally well to the ST peptide (Fig. 2B), indicating that binding of ST was not compromised in these mutant receptors. Reports have suggested that in the event of mutation of a glycosylation site, proximal sites can undergo glycosylation (39, 40). We thus speculated that the functional consequences in the event of a mutation at either Asn75 or Asn79 could be alleviated by glycosylation at the alternative site. To test this hypothesis, both Asn residues were mutated together (GC-CΔN75N79), and the mutant receptor was characterized. Western blot analysis of cells expressing GC-CΔN75N79 showed that the receptor had reduced glycosylation, based on increased electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 4D). The mutant receptor had traversed the secretory pathway as inferred by the presence of a higher glycosylated form of GC-CΔN75N79 (Fig. 4D). In vitro guanylyl cyclase activity of the GC-CΔN75N79 mutant in the presence of MnGTP was unimpaired (Fig. 4E). However, receptor binding assays on membranes prepared from cells expressing GC-CΔN75N79 indicated a marked decrease in ligand binding activity (Fig. 4F). The fraction of receptor that did bind (∼ 25% of the wild type receptor) showed an affinity for ST that was similar to that of the wild type receptor.

The lack of ST binding led to a decrease in ST-mediated cGMP production by GC-CΔN75N79 (Fig. 4G). Because the single site mutants at Asn75 or Asn79 were not compromised in terms of activity (Fig. 2), glycosylation at either Asn75 or Asn79 appears to be critical for the folding of GC-C to achieve a conformation that is able to bind ST.

Asn75 is not present in porcine GC-C (supplemental Fig. 4), indicating that the roles of glycosylation at Asn75 and Asn79 are specific for the folding and functioning of human GC-C. Thus, species specificity in the roles of glycosylation in some proteins exists and should be appreciated.

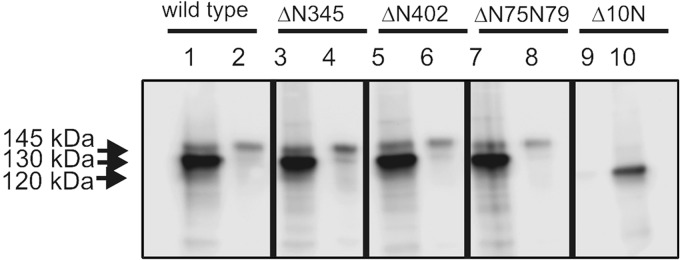

Effect of Glycosylation Site Mutations on Trafficking of GC-C

Aberrant or insufficient glycosylation of proteins can lead to a reduction in their trafficking to the cell surface. We therefore monitored the plasma membrane localization of mutants that were compromised in ST binding and ST-mediated cGMP production. Cell surface biotinylation was carried out on cells expressing GC-CΔ10N, GC-CΔN345, GC-CΔN402, and GC-CΔN75N79. As seen in Fig. 5, only GC- CΔ10N did not traffic to the surface of cells, indicating that the lower cGMP production by the other mutant receptors was not a consequence of reduced surface localization.

FIGURE 5.

Surface localization of glycosylation-deficient mutants of GC-C. Monolayer cultures of cells expressing either wild type or indicated glycosylation mutants of GC-C were treated with a cell impermeable analog of biotin. Biotinylated proteins were pulled down using streptavidin-conjugated beads, and bound protein was analyzed by Western blotting using the GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody. Lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 represent the load, and lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 9 represent the proteins associated with the streptavidin beads. Data shown in representative of experiments were repeated twice.

Analysis of GC-CΔ4N and GC-CΔ6N′

Until now, we have identified four important sites of glycosylation involved in folding of GC-C that allow binding of ST (Asn75 and Asn79) and ligand-mediated activation of GC-C (Asn345 and Asn402). Therefore, a mutant receptor that removes these four crucial glycosylation sites should severely compromise GC-C function. Conversely, the presence of only these four glycosylation sites on the receptor may suffice for its function. To test this hypothesis, GC-CΔ4N (ΔN75+N79+N345+N402) and GC-CΔ6N′ (ΔN32+N195+N284+N307+N313+N357) were generated. Western blot analysis of HEK293T cells expressing these mutant receptors showed that both exhibited an increased electrophoretic mobility in comparison with wild type GC-C (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Characterization of GC-CΔ4N and GC-CΔ6N′. A, membrane protein (40 μg) from HEK293T cells expressing mutant GC-C receptors was subjected to Western blot analysis using GCC:C8 monoclonal antibody. B, receptor binding analysis was carried using membrane proteins (40 μg) from cells expressing the wild type or mutant receptor. Data are representative of experiments carried out twice. Values shown are the mean ± S.E. of experiments performed twice. C, in vitro ST-mediated cGMP production was measured using membrane proteins (10 μg) from cells expressing the indicated GC-C mutant using MgGTP as substrate. Data shown are mean ± S.E. from a representative experiment, with experiments performed twice, with duplicate determinations. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Student's t test. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001.

Membrane proteins from cells expressing similar amounts of either the mutants or wild type receptors were tested for ST binding ability. There was a significant (∼70%) reduction in the Bmax of GC-CΔ4N, in agreement with the fact that glycosylation was required at Asn75 and Asn79 to allow efficient ST binding (Fig. 6B). However, the extent of binding exhibited by GC-CΔ6N′ was still 30% less than that seen for equivalent expression of the wild type receptor.

Ligand-mediated activation was tested in membrane fractions prepared from cells expressing the mutant receptors, and as expected from the binding data, GC-CΔ4N showed ∼80% lower ST-mediated guanylyl cyclase activation (Fig. 6C). GC-CΔ6N′ showed ∼40% lower ST-mediated activation in comparison with the wild type receptor (Fig. 6C) but significantly higher than that seen with GC-CΔ4N. Therefore, glycosylation at Asn75, Asn79, Asn345, and Asn402 is important for the correct folding of GC-C, but additional sites need to be glycosylated to completely stabilize the wild type conformation of the extracellular domain.

The VIP36 Lectin Chaperone May Be Involved in GC-C Quality Control

Proteins that transit through the secretory pathway are subject to quality control, both by chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus (41). An early Golgi-resident lectin chaperone is VIP36, which plays a role in both the onward trafficking of its cargo (42, 43) as well as in retrograde transport of misfolded proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum (44). We thus investigated a possible interaction between GC-C and VIP36. We transfected HEK293 cells stably expressing GC-C with wild type VIP36 or a mutant deficient in lectin binding activity (VIP36Lec−) and verified the interaction of VIP36 and GC-C by co-immunoprecipitation. We observed that VIP36 associated with GC-C, whereas a VIP36 mutant deficient in lectin binding did not co-immunoprecipitate with GC-C (Fig. 7A). Therefore, association of VIP36 and GC-C was dependent on glycosylation of GC-C. To our knowledge, this is the first identification of a cell surface receptor that serves as a client for VIP36.

FIGURE 7.

Interaction of GC-C with VIP36. A, Myc-tagged VIP36 or Myc-tagged VIP36Lec− were expressed in HEK293 cells stably expressing GC-C. GC-C was immunoprecipitated 72 h following transfection, and the immune complex was subjected to Western blot analysis using GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody or anti-Myc antibody (9E10) to detect VIP36. Data shown are representative of experiments performed thrice. B, membrane proteins from cells expressing either wild type GC-C, GC-CΔN345, GC-CΔN402, or GC-CΔN75N79 were interacted with GST-VIP36 immobilized on GSH-agarose beads, in the absence or presence of 20 mm mannose. The proteins associated with the beads were subject to Western blot analysis using GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody, and an aliquot of the pulldown was taken for SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (lower panel). Data shown are representative of experiments performed three times. C, membrane proteins from cells expressing either wild type GC-C, GC-CΔN345N402, or GC-CΔ75ΔN79 were interacted with GST or GST-VIP36 immobilized on GSH-agarose beads, in the absence or presence of 20 mm mannose. The proteins associated with the beads were subject to Western blot analysis using GC-C:C8 monoclonal antibody. An aliquot of the pulldown was subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue stain to normalize the amount of GST and GST-VIP36 used in the pulldown assay (lower panel). Data shown are representative of experiments performed twice.

VIP36 may function as a quality control mechanism where misfolded or partially folded forms of GC-C are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum to allow another round of folding (45). To analyze the interaction of VIP36 and apparently misfolded mutants of GC-C, we performed a pulldown assay with GST-VIP36 and solubilized membranes from cells expressing either wild type, ΔN402, ΔN345, or the ΔN75N79 mutant receptors. As seen in Fig. 7B, the 130-kDa, high mannose form of GC-C was able to interact with VIP36, and this interaction was abolished in the presence of mannose. Interestingly, increased interaction of the 130-kDa forms of GC-CΔ345 and GC-CΔ402 was seen, suggesting that VIP36 was able to “survey” and bind to misfolded forms of GC-C. However, no interaction of the ΔN75N79 receptor was seen with VIP36, even though this receptor was severely compromised in terms of ST binding (Fig. 7B).

We hypothesized that glycosylation at Asn75 and Asn79 was primarily required for interaction with VIP36. We therefore compared the interaction of VIP36 with GC-CΔ4N, and the double mutant GC-CΔN345N402. Although GC-CΔN345N402 continued to show an increased interaction with VIP36, a marked reduction in the interaction of the GC-CΔ4N mutant receptor was seen, where glycosylation at Asn75 and Asn79 was abolished (Fig. 7C). This demonstrated therefore that glycosylation at specific sites in a protein can determine interaction with VIP36.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have established the critical requirements of glycosylation in GC-C, not only in facilitating proper folding to generate a form that is competent in ligand binding but also allowing optimum cGMP production following ligand binding (Fig. 8). These results have therefore elucidated yet another nuance in the regulation in this receptor.

FIGURE 8.

Distribution of putative glycosylation sites in the ECD of human GC-C. Glycosylation at sites Asn75 and Asn79 are required to allow ST binding and mediate interactions with VIP36. Glycosylation at Asn345 and Asn402 modulate ligand-mediated GC-C activation. Residues at Asn313 and Asn357 are not glycosylated, and additional sites are probably involved in overall stability of the extracellular domain.

It is important to note that misfolding in the extracellular domain of GC-C in no way alters the catalytic activity of the intracellular guanylyl cyclase domain. Even completely deglycosylated GC-C retains guanylyl cyclase activity (Fig. 1C), indicating the complete compartmentalization of folding of this multidomain protein. Glycosylation at specific sites (Asn75 and Asn79) is important for allowing the receptor to adopt a conformation amenable for ligand binding (Fig. 4). Glycosylation at distinct sites (Asn345 and Asn402) are not required for ligand binding but affects activation of the receptor and the transmission of information of the ligand-binding event in the extracellular domain to the C-terminal guanylyl cyclase domain (Fig. 3). Importantly, we show that although the porcine and human receptors show a significant conservation of Asn residues that could act as sites of glycosylation (supplemental Fig. 4), the role of glycosylation at these individual sites differ in the two species. These findings highlight how similar receptors can follow a different folding trajectory in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex during their transit to the plasma membrane, dependent on glycosylation at specific sites.

The low sequence similarity in the extracellular domains of receptor guanylyl cyclases (5) and an apparent species specificity of the roles of individual sites of glycosylation preclude a generalization on the interactions between the glycan moiety and the receptor backbone and/or peptide ligand. Indeed, there is little conservation of the sites of glycosylation in different receptor guanylyl cyclases (46), and human retinal guanylyl cyclase (GC-F) has no putative glycosylation sites in its extracellular domain (47). GC-A and GC-B are glycosylated at five sites in the extracellular domain (36, 48), and in a manner similar to GC-C, deglycosylation of GC-A following trafficking to the cell surface did not affect ligand binding (48). Crystal structures of the extracellular domain of rat GC-A show no interactions between the glycan and the receptor peptide backbone, in either the hormone-bound or free structures (48, 49). However, structures of human NPR-C revealed that glycosyl moieties form extensive interactions with the protein backbone, and these interactions were lost on hormone binding (50). Although one study with bovine GC-B indicated that glycosylation at a specific site was important for ligand binding (36), glycosylation at the corresponding position in rat and mouse GC-B cannot occur because the Asn residue at that position is replaced by a Glu in the rodent receptors (36). It therefore appears that the role of glycosylation in receptor guanylyl cyclases has evolved specifically for each protein, in a species-dependent manner. Species-specific novel glycosylation sites may impart an alternate means of regulating receptor activity as seen in the primate β2-adrenergic receptor (51), the tetrapod epidermal growth factor receptor (52), and the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (53).

VIP36 is postulated to be a cargo receptor transporting immature or misfolded glycoproteins from the Golgi back to the endoplasmic reticulum in a retrograde manner (45). To date, all clients for VIP36 have been reported to be secreted glycoproteins. VIP36 facilitates anterograde trafficking of clusterin in Madin Darby canine kidney cells (42) and α-amylase in the rat parotid gland (43). On the contrary, VIP36 impedes the secretion of α1-antityrpsin in human hepatocellular liver carcinoma cells, indicating its involvement in retrograde transport (45). Here, we show that VIP36 may also identify the glycosylated and misfolded extracellular domain of a cell surface receptor. VIP36 interacts with the endoplasmic reticulum-resident chaperone BiP (44), and therefore, VIP36 may deliver misfolded GC-C to BiP for a further round of folding.

VIP36 interacts with high mannose-type glycans and may protect these residues from trimming by cis-Golgi mannosidases (45). The 145-kDa form of GC-C contains high mannose, based on its sensitivity to endoglycosidase H (22) and because VIP36 fails to interact with GC-C when glycosylation at Asn75 and Asn79 are abolished (Fig. 7, B and C), this may suggest that high mannose glycans may be found at either one or both of these sites. In polarized epithelial cells, VIP36 is found to predominantly localize on the apical surface and facilitate apical membrane secretion of proteins (54). GC-C is also found on the apical surface in human colonic cell lines such as T84 and Caco2 (55, 56) and also following heterologous expression in Madin Darby canine kidney cells (57). Apical sorting of GC-C was found to be dependent on the C terminus in Madin Darby canine kidney cells (57), but it is conceivable that VIP36 may assist in apical trafficking of GC-C in intestinal cells. In rat small intestinal cells, GC-C was found only in the brush border membrane (58), but in colonocytes, significant ST-binding activity was detected in the basolateral membrane (59). Whether this differential localization could be correlated with different levels of VIP36 in these two regions of the intestine remains to be seen.

Enzymes that modify glycosylation are expressed in a tissue-specific manner (60). Therefore, differential glycosylation in various tissues may play a role in regulating the activity of GC-C at its sites of extraintestinal expression, such as the kidney (61), brain (13), and liver (62). Changes in glycosylation accompany diseases of the intestine (63–65), and congenital disorders of glycosylation (66) may also affect GC-C expression and activity. Enhanced N-glycan branching has been shown to reduce receptor endocytosis (67), suggesting that glycosylation may regulate both cell surface expression and activity of GC-C in different cell types. Finally, glycan-dependent interactions with secreted lectins (68) may regulate GC-C activity, and this would again be determined by the nature and extent of its glycosylation in different cell types. Because VIP36 is the first lectin that has been shown to associate with GC-C in a functional manner, it may be worthwhile to investigate other such interacting partners of GC-C, thus opening up new avenues of glycan-dependent cross-talk in the GC-C signaling pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Vani Iyer in the purification and iodination of ST peptides. We acknowledge Dr. Akhila Chandrashaker for initiating some of these studies, Radhika Apte for technical assistance, and members of the laboratory for useful discussions.

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology (India).

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–5.

- ST

- heat-stable enterotoxin peptide

- GC-A

- guanylyl cyclase A

- GC-B

- guanylyl cyclase B

- GC-C

- guanylyl cyclase C

- PNGase F

- Peptide-N-Glycosidase F

- VIP 36

- vesicular integral membrane protein of 36 kDa.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown K. H. (2003) Diarrhea and malnutrition. J. Nutr. 133, 328S-332S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Field M., Graf L. H., Jr., Laird W. J., Smith P. L. (1978) Heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli: in vitro effects on guanylate cyclase activity, cyclic GMP concentration, and ion transport in small intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75, 2800–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamra F. K., Forte L. R., Eber S. L., Pidhorodeckyj N. V., Krause W. J., Freeman R. H., Chin D. T., Tompkins J. A., Fok K. F., Smith C. E. (1993) Uroguanylin: structure and activity of a second endogenous peptide that stimulates intestinal guanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 10464–10468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Currie M. G., Fok K. F., Kato J., Moore R. J., Hamra F. K., Duffin K. L., Smith C. E. (1992) Guanylin: an endogenous activator of intestinal guanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 947–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basu N., Arshad N., Visweswariah S. S. (2010) Receptor guanylyl cyclase C (GC-C): regulation and signal transduction. Mol Cell Biochem. 334, 67–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kopic S., Geibel J. P. (2010) Toxin mediated diarrhea in the 21 century: the pathophysiology of intestinal ion transport in the course of ETEC, V. cholerae and rotavirus infection. Toxins 2, 2132–2157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pitari G. M., Zingman L. V., Hodgson D. M., Alekseev A. E., Kazerounian S., Bienengraeber M., Hajnóczky G., Terzic A., Waldman S. A. (2003) Bacterial enterotoxins are associated with resistance to colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2695–2699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pitari G. M., Di Guglielmo M. D., Park J., Schulz S., Waldman S. A. (2001) Guanylyl cyclase C agonists regulate progression through the cell cycle of human colon carcinoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7846–7851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin J. E., Li P., Snook A. E., Schulz S., Dasgupta A., Hyslop T. M., Gibbons A. V., Marszlowicz G., Pitari G. M., Waldman S. A. (2010) The hormone receptor GUCY2C suppresses intestinal tumor formation by inhibiting AKT signaling. Gastroenterology 138, 241–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kazerounian S., Pitari G. M., Shah F. J., Frick G. S., Madesh M., Ruiz-Stewart I., Schulz S., Hajnóczky G., Waldman S. A. (2005) Proliferative signaling by store-operated calcium channels opposes colon cancer cell cytostasis induced by bacterial enterotoxins. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314, 1013–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schulz S., Lopez M. J., Kuhn M., Garbers D. L. (1997) Disruption of the guanylyl cyclase-C gene leads to a paradoxical phenotype of viable but heat-stable enterotoxin-resistant mice. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 1590–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Valentino M. A., Lin J. E., Snook A. E., Li P., Kim G. W., Marszalowicz G., Magee M. S., Hyslop T., Schulz S., Waldman S. A. (2011) A uroguanylin-GUCY2C endocrine axis regulates feeding in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3578–3588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gong R., Ding C., Hu J., Lu Y., Liu F., Mann E., Xu F., Cohen M. B., Luo M. (2011) Role for the membrane receptor guanylyl cyclase-C in attention deficiency and hyperactive behavior. Science 333, 1642–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiskerstrand T., Arshad N., Haukanes B. I., Tronstad R. R., Pham K. D., Johansson S., Håvik B., Tønder S. L., Levy S. E., Brackman D., Boman H., Biswas K. H., Apold J., Hovdenak N., Visweswariah S. S., Knappskog P. M. (2012) Familial diarrhea syndrome caused by an activating GUCY2C mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 1586–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Romi H., Cohen I., Landau D., Alkrinawi S., Yerushalmi B., Hershkovitz R., Newman-Heiman N., Cutting G. R., Ofir R., Sivan S., Birk O. S. (2012) Meconium ileus caused by mutations in GUCY2C, encoding the CFTR-activating guanylate cyclase 2C. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 893–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jaleel M., Saha S., Shenoy A. R., Visweswariah S. S. (2006) The kinase homology domain of receptor guanylyl cyclase C: ATP binding and identification of an adenine nucleotide sensitive site. Biochemistry 45, 1888–1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhandari R., Srinivasan N., Mahaboobi M., Ghanekar Y., Suguna K., Visweswariah S. S. (2001) Functional inactivation of the human guanylyl cyclase C receptor: modeling and mutation of the protein kinase-like domain. Biochemistry 40, 9196–9206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saha S., Biswas K. H., Kondapalli C., Isloor N., Visweswariah S. S. (2009) The linker region in receptor guanylyl cyclases is a key regulatory module: mutational analysis of guanylyl cyclase C. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27135–27145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basu N., Bhandari R., Natarajan V. T., Visweswariah S. S. (2009) Cross talk between receptor guanylyl cyclase C and c-src tyrosine kinase regulates colon cancer cell cytostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 5277–5289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crane J. K., Shanks K. L. (1996) Phosphorylation and activation of the intestinal guanylyl cyclase receptor for Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin by protein kinase C. Mol. Cell Biochem. 165, 111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghanekar Y., Chandrashaker A., Visweswariah S. S. (2003) Cellular refractoriness to the heat-stable enterotoxin peptide is associated with alterations in levels of the differentially glycosylated forms of guanylyl cyclase C. Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 3848–3857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghanekar Y., Chandrashaker A., Tatu U., Visweswariah S. S. (2004) Glycosylation of the receptor guanylate cyclase C: role in ligand binding and catalytic activity. Biochem. J. 379, 653–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamashita K., Hara-Kuge S., Ohkura T. (1999) Intracellular lectins associated with N-linked glycoprotein traffic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1473, 147–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Singh S., Singh G., Heim J. M., Gerzer R. (1991) Isolation and expression of a guanylate cyclase-coupled heat stable enterotoxin receptor cDNA from a human colonic cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 179, 1455–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shenoy A. R., Visweswariah S. S. (2003) Site-directed mutagenesis using a single mutagenic oligonucleotide and DpnI digestion of template DNA. Anal. Biochem. 319, 335–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Visweswariah S. S., Ramachandran V., Ramamohan S., Das G., Ramachandran J. (1994) Characterization and partial purification of the human receptor for the heat-stable enterotoxin. Eur. J. Biochem. 219, 727–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shirakabe K., Hattori S., Seiki M., Koyasu S., Okada Y. (2011) VIP36 protein is a target of ectodomain shedding and regulates phagocytosis in macrophage Raw 264.7 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 43154–43163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kawasaki N., Matsuo I., Totani K., Nawa D., Suzuki N., Yamaguchi D., Matsumoto N., Ito Y., Yamamoto K. (2007) Detection of weak sugar binding activity of VIP36 using VIP36-streptavidin complex and membrane-based sugar chains. J Biochem. 141, 221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bakre M. M., Ghanekar Y., Visweswariah S. S. (2000) Homologous desensitization of the human guanylate cyclase C receptor. Cell-specific regulation of catalytic activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benoit I., Asther M., Sulzenbacher G., Record E., Marmuse L., Parsiegla G., Gimbert I., Asther M., Bignon C. (2006) Respective importance of protein folding and glycosylation in the thermal stability of recombinant feruloyl esterase A. FEBS Lett. 580, 5815–5821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao X., Zhang P., Liu Q., He F., Feng L., Han H. (2010) Expression, purification and characterization of the extracellular domain of human Flt3 ligand in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Rep. 37, 2301–2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nandi A., Mathew R., Visweswariah S. S. (1996) Expression of the extracellular domain of the human heat-stable enterotoxin receptor in Escherichia coli and generation of neutralizing antibodies. Protein Expr. Purif. 8, 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hasegawa M., Hidaka Y., Wada A., Hirayama T., Shimonishi Y. (1999) The relevance of N-linked glycosylation to the binding of a ligand to guanylate cyclase C. Eur. J. Biochem. 263, 338–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lauber T., Tidten N., Matecko I., Zeeb M., Rösch P., Marx U. C. (2009) Design and characterization of a soluble fragment of the extracellular ligand-binding domain of the peptide hormone receptor guanylyl cyclase-C. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 22, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwarz F., Aebi M. (2011) Mechanisms and principles of N-linked protein glycosylation. Curr. Opin Struct. Biol. 21, 576–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fenrick R., Bouchard N., McNicoll N., De Léan A. (1997) Glycosylation of asparagine 24 of the natriuretic peptide receptor-B is crucial for the formation of a competent ligand binding domain. Mol. Cell Biochem. 173, 25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi X., Elliott R. M. (2004) Analysis of N-linked glycosylation of hantaan virus glycoproteins and the role of oligosaccharide side chains in protein folding and intracellular trafficking. J. Virol. 78, 5414–5422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Delos S. E., Burdick M. J., White J. M. (2002) A single glycosylation site within the receptor-binding domain of the avian sarcoma/leukosis virus glycoprotein is critical for receptor binding. Virology 294, 354–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lanctot P. M., Leclerc P. C., Clément M., Auger-Messier M., Escher E., Leduc R., Guillemette G. (2005) Importance of N-glycosylation positioning for cell-surface expression, targeting, affinity and quality control of the human AT1 receptor. Biochem. J. 390, 367–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dong M., Liu H., Tepp W. H., Johnson E. A., Janz R., Chapman E. R. (2008) Glycosylated SV2A and SV2B mediate the entry of botulinum neurotoxin E into neurons. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 5226–5237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arvan P., Zhao X., Ramos-Castaneda J., Chang A. (2002) Secretory pathway quality control operating in Golgi, plasmalemmal, and endosomal systems. Traffic 3, 771–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hara-Kuge S., Ohkura T., Ideo H., Shimada O., Atsumi S., Yamashita K. (2002) Involvement of VIP36 in intracellular transport and secretion of glycoproteins in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16332–16339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hara-Kuge S., Seko A., Shimada O., Tosaka-Shimada H., Yamashita K. (2004) The binding of VIP36 and α-amylase in the secretory vesicles via high-mannose type glycans. Glycobiology 14, 739–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nawa D., Shimada O., Kawasaki N., Matsumoto N., Yamamoto K. (2007) Stable interaction of the cargo receptor VIP36 with molecular chaperone BiP. Glycobiology 17, 913–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reiterer V., Nyfeler B., Hauri H. P. (2010) Role of the lectin VIP36 in post-ER quality control of human α1-antitrypsin. Traffic 11, 1044–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van den Akker F. (2001) Structural insights into the ligand binding domains of membrane bound guanylyl cyclases and natriuretic peptide receptors. J. Mol. Biol. 311, 923–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koch K. W., Stecher P., Kellner R. (1994) Bovine retinal rod guanyl cyclase represents a new N-glycosylated subtype of membrane-bound guanyl cyclases. Eur. J. Biochem. 222, 589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Miyagi M., Zhang X., Misono K. S. (2000) Glycosylation sites in the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor: oligosaccharide structures are not required for hormone binding. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5758–5768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van den Akker F., Zhang X., Miyagi M., Huo X., Misono K. S., Yee V. C. (2000) Structure of the dimerized hormone-binding domain of a guanylyl-cyclase-coupled receptor. Nature 406, 101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. He X. l., Chow D. c., Martick M. M., Garcia K. C. (2001) Allosteric activation of a spring-loaded natriuretic peptide receptor dimer by hormone. Science 293, 1657–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mialet-Perez J., Green S. A., Miller W. E., Liggett S. B. (2004) A primate-dominant third glycosylation site of the β2-adrenergic receptor routes receptors to degradation during agonist regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38603–38607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stein R. A., Staros J. V. (2006) Insights into the evolution of the ErbB receptor family and their ligands from sequence analysis. BMC Evol. Biol. 6, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kaczur V., Puskás L. G., Takács M., Rácz I. A., Szendroi A., Tóth S., Nagy Z., Szalai C., Balázs C., Falus A., Knudsen B., Farid N. R. (2003) Evolution of the thyrotropin receptor: a G protein coupled receptor with an intrinsic capacity to dimerize. Mol. Genet. Metab. 78, 275–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vagin O., Kraut J. A., Sachs G. (2009) Role of N-glycosylation in trafficking of apical membrane proteins in epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296, F459–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Forte L. R., Eber S. L., Turner J. T., Freeman R. H., Fok K. F., Currie M. G. (1993) Guanylin stimulation of Cl- secretion in human intestinal T84 cells via cyclic guanosine monophosphate. J. Clin. Invest. 91, 2423–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Scott R. O., Thelin W. R., Milgram S. L. (2002) A novel PDZ protein regulates the activity of guanylyl cyclase C, the heat-stable enterotoxin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22934–22941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hodson C. A., Ambrogi I. G., Scott R. O., Mohler P. J., Milgram S. L. (2006) Polarized apical sorting of guanylyl cyclase C is specified by a cytosolic signal. Traffic 7, 456–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. De Jonge H. R. (1975) The localization of guanylate cyclase in rat small intestinal epithelium. FEBS Lett. 53, 237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Albano F., Brasitus T., Mann E. A., Guarino A., Giannella R. A. (2001) Colonocyte basolateral membranes contain Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284, 331–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Parekh R. B., Tse A. G., Dwek R. A., Williams A. F., Rademacher T. W. (1987) Tissue-specific N-glycosylation, site-specific oligosaccharide patterns and lentil lectin recognition of rat Thy-1. EMBO J. 6, 1233–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jaleel M., London R. M., Eber S. L., Forte L. R., Visweswariah S. S. (2002) Expression of the receptor guanylyl cyclase C and its ligands in reproductive tissues of the rat: a potential role for a novel signaling pathway in the epididymis. Biol. Reprod 67, 1975–1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mann E. A., Shanmukhappa K., Cohen M. B. (2010) Lack of guanylate cyclase C results in increased mortality in mice following liver injury. BMC Gastroenterol 10, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hayes C. A., Nemes S., Karlsson N. G. (2012) Statistical analysis of glycosylation profiles to compare tissue type and inflammatory disease state. Bioinformatics 28, 1669–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Balog C. I., Stavenhagen K., Fung W. L., Koeleman C. A., McDonnell L. A., Verhoeven A., Mesker W. E., Tollenaar R. A., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2012) N-glycosylation of colorectal cancer tissues: a liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry-based investigation. Mol. Cell Proteomics 11, 571–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Campbell B. J., Yu L. G., Rhodes J. M. (2001) Altered glycosylation in inflammatory bowel disease: a possible role in cancer development. Glycoconj. J. 18, 851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zentilin Boyer M., de Lonlay P., Seta N., Besnard M., Pélatan C., Ogier H., Hugot J. P., Faure C., Saudubray J. M., Navarro J., Cézard J. P. (2003) [Failure to thrive and intestinal diseases in congenital disorders of glycosylation]. Arch. Pediatr. 10, 590–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lau K. S., Partridge E. A., Grigorian A., Silvescu C. I., Reinhold V. N., Demetriou M., Dennis J. W. (2007) Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell 129, 123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Delacour D., Koch A., Jacob R. (2009) The role of galectins in protein trafficking. Traffic 10, 1405–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.