The profession of pharmacy is changing quickly — everything from our scope of practice to our business models. These changes enable pharmacists to use their clinical knowledge and years of experience to provide patients with the best possible care. During one of my co-op rotations (4 months at a community pharmacy, where I helped conduct medication reviews), I encountered my first patient with strong suicidal thoughts, which prompted me to write this article.

Currently, only a few papers have been published discussing the impact of pharmacist intervention to improve outcomes in major depression and none specifically regarding suicide prevention.1 Because of this gap, I decided that an article from a student's practice perspective might start a discussion in the profession.

My experience started out just like any other — a medication review that began with a bit of friendly chatter and a discussion about healthy lifestyles. When the talk turned to alcohol consumption and smoking habits, this prompted more discussion about the patient's mental health. The patient was drinking nightly, smoking heavily and spoke of his family history with suicide. This particular patient was, on the outside, a very friendly and charismatic individual, but clearly was majorly depressed and fatigued.

The most recent statistics in Canada show the annual incidence of suicide to be 0.01% of the total population, or approximately 10 suicides for every 100,000 persons.2 In the neighbouring United States approximately 0.7% and 5.6% of the general population attempted suicide or have suicidal ideations each year, respectively.3 Successful suicide is rare, making it difficult to predict.4 In Ontario, a patient's annual MedsCheck (medication review) is an opportune time for a pharmacist to evaluate a patient's suicidal characteristics, thoughts, plans and behaviours. It is important to note, though, that studies have indicated that about 45% of those who commit suicide had had contact with primary care providers within their last month of life.5

Because of my experience, I believe pharmacists may prove to be critical in decreasing the number of successful suicide cases each year in North America. As pharmacists, we can play a role in helping patients in this situation through collaboration with other health care professionals and the use of pharmaceutical care.1,6 With my case, the patient felt more comfortable opening up to the pharmacist and myself about his thoughts, plans and behaviours rather than to his primary physician. Why? Because he felt too embarrassed to speak to his physician, as they were close friends. So how did we proceed with this patient?

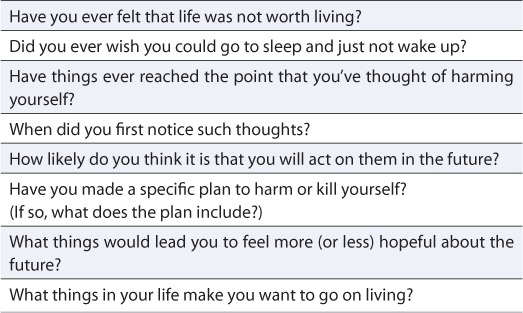

Simply asking the patient about suicidal ideation may not yield truthful results, so it is advantageous to complete a small psychiatric evaluation through a series of probing questions. There are 5 important areas to cover:

The patient's current presentation of suicidality

Previous or current psychiatric illness

History (includes family and close friends)

Psychosocial situation (socioeconomic status, family conflict, cultural or religious beliefs)

Individual strengths and vulnerabilities

Specific questions that can help pharmacists gain this information can be found in Table 1.4

TABLE 1.

Information-gathering questions for pharmacists with suicidal patients4

In my patient's case, it was very important to estimate his suicide risk, because I asked myself, “What were his plans for the rest of the day? Would it be in the patient's best interest to let him go home that night?” There are a multitude of factors that are associated with an increased risk for suicide, such as current suicidal thoughts, the existence of a major depressive disorder or recent unemployment.4

After completing the assessment and recording all information gathered from the patient, the pharmacist and I created a plan. For our patient, the plan involved plenty of collaboration with his physician, a change in pharmacotherapy and the addition of protective factors. Protective factors can consist of arranging for additional care through a social support system, dispensing in smaller quantities and completing a cabinet clean-up. The care plan should also include and is not limited to: pharmacotherapy alternatives (such as antidepressants); psychosocial interventions (psychotherapy); education of the patient and family (addressing patient safety); and promotion of adherence to the treatment plan.4

There are a few pharmacotherapy alternatives used as treatment, which pharmacists should be aware of in the event a clinician requests a recommendation. Here are some alternatives to keep in mind:

Antidepressant therapy has been used for those patients also suffering from acute, recurrent and chronic depressive disorders; however, controversy over the potential increased risk of suicidality with the initiation of these agents requires that a risk versus benefit analysis be done for each patient.7

Lithium has strong evidence supporting its long-term use in patients with recurring bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder in order to reduce the risk of suicide.4

Mood-stabilizing anticonvulsant agents and antipsychotics, in particular clozapine, have been reported to reduce the rates of suicide attempts and hospitalizations due to suicide attempts and are a viable option for the treatment of these patients.4,8

Safety is the number one issue when dealing with potentially suicidal patients. After speaking to my patient, I felt an exceptionally strong sense of responsibility to ensure he did not harm himself, so the right treatment setting was also a very important part of the plan. Hospitalization is generally indicated after a suicide or aborted suicide attempt when the patient is psychotic, in distress or the attempt was violent in nature.4 A partial hospital and intensive outpatient program is indicated for an attempt or aborted attempt in all other cases that do not fall into the above category.4 Outpatient treatment may be more beneficial in cases where the patient has a safe and supportive living situation and is available for ongoing psychiatric care.4 My patient ended up receiving additional treatment in the hospital shortly after our meeting, followed by an intensive outpatient program.

As health care providers, pharmacists are not only responsible for caring for patients presenting with suicidal ideations, but are also responsible for taking care of themselves. Dealing with such patients can be the cause of increased stress and, in the event of patient death by suicide, loss of professional self-esteem.4 Even as a student under the direct supervision of a pharmacist, I felt the need to talk to someone about my experience, especially since my patient was hospitalized. In either case, pharmacists should seek support from colleagues and make use of consultations available through their respective colleges or associations.

I hope through my experience you will be inspired to learn more about this topic and discuss it with colleagues, whether other pharmacists, physicians, psychiatrists, nurses or social workers. I really do believe our profession can prove to be critical in decreasing the number of successful suicide cases each year in North America.

|

References

- 1.Boudreau DM, Capoccia KL, Sullivan SD, et al. Collaboration care model to improve outcomes in major depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:585–91. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada. Suicide and suicide rate, by sex and age group. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/hlth66a-eng.htm (accessed September 15, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby AE, Cheltenham MP, Sacks JJ. Incidence of suicidal ideation and behavior in the United States, 1994. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs DG, Baldessarini RJ, Conwell Y, et al. Practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psych. 2003;160(supplement)(11):1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Høifødt TS, Talseth AG. Dealing with suicidal patients — a challenging task: a qualitative study of young physicians' experiences. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice: the clinician's guide. 2nd edition. New York: McGraw Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nierenberg AA, Leon AC, Price LH, et al. Crisis of confidence: antidepressant risk versus benefit. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):e11. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10035tx2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asenjo LC, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, et al. Clozapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(11):CD006633. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006633.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]