Abstract

Background: Evolving scope of practice has led pharmacists to develop new skills traditionally performed by other members of the health care team, including physical examination (PE). A session to teach PE skills to pharmacists was created as part of a professional development program. The purpose of this study was to evaluate participants' perception of, barriers to and confidence in performing PE before and after the session.

Methods: A 2-hour session introduced participants to PE as part of a primary care professional development program. Surveys were administered before and after the session, and then 4 weeks later. Participants' confidence in performing PE was assessed using a 4-point unipolar scale questionnaire, and mean weighted responses were compared between the pre- and post-session surveys.

Results: Thirty-four pharmacists participated in the study. At baseline, 82.4% had never received formal PE education, but 38.2% performed PE in practice, including blood pressure measurement. Eighty-two percent of participants identified barriers to performing PE, the most common being lack of formal training. Participants' confidence with PE significantly increased between the pre- and post-session surveys, except for comfort with making drug therapy interventions based on PE findings. Forty-three percent of participants completed the 4-week follow-up survey, which demonstrated that the use of PE in practice remained unchanged.

Conclusion: Prior to the session, most participants did not use PE in their practice, primarily due to a lack of formal training. The session significantly improved participants' confidence in PE, but this did not translate into short-term practice change.

Background

Pharmacy practice has been evolving over the past few decades, from simple medication dispensing to more direct patient care activities, often referred to as clinical pharmacy. The American College of Clinical Pharmacy has defined this as the practice of providing patient care that optimizes medication therapy and promotes health, wellness and disease prevention.1 Pharmacists are increasingly becoming integral members of health care teams, and are responsible for collaborating with other team members to ensure that patients receive optimal drug therapy. Furthermore, pharmacists continue to expand their role by increasing their clinical skills and knowledge base. In recent years, pharmacists in some regions of Canada have been granted a new, expanded scope-of-practice through legislation.2–5 This has allowed pharmacists to embrace new responsibilities, such as adapting prescriptions, administering injectable medications, accessing and ordering laboratory values and even prescribing independently. Along with this expanded scope of practice, pharmacists have sought to broaden and advance their knowledge base and skills to include other patient care activities traditionally performed by other members of the health care team, such as physical examination (PE).

KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE.

Knowledge of physical examination (PE) will allow pharmacists to enhance their assessment of drug therapy, expand their scope of practice and increase their value on the health care team.

The main barrier identified to pharmacists performing PE is a lack of formal training.

This study demonstrates that a session specifically designed to teach PE to pharmacists resulted in improved knowledge and confidence in performing PE, though this did not translate into short-term practice change. Therefore, expanded knowledge of PE alone is not sufficient to further the implementation of PE in practice.

Further studies are warranted to evaluate methods of improving pharmacists' use of PE in practice by addressing individual and practice-specific barriers.

MISE EN PRATIQUE DES CONNAISSANCES.

La connaissance de l'examen physique (EP) permettra aux pharmaciens de faire une meilleure évaluation de la pharmacothérapie, d'étendre leur champ d'activité et de jouer un rôle plus utile au sein de l'équipe de soins.

Selon les pharmaciens, le manque de formation structurée constitue le principal obstacle à l'exécution de l'EP.

Cette étude montre qu'une séance de formation ayant pour but précis d'enseigner aux pharmaciens comment réaliser un EP a permis d'améliorer leurs connaissances du sujet et leur confiance dans l'exécution de l'EP; cette formation ne s'est toutefois pas traduite par des changements à court terme dans la pratique des pharmaciens. Il ne suffit donc pas d'approfondir les connaissances sur l'EP pour en accroître l'utilisation en pratique clinique.

D 'autres études devront être menées pour évaluer des moyens d'accroître l'utilisation de l'EP dans la pratique des pharmaciens, en s'attaquant aux obstacles individuels et aux obstacles propres à la pratique.

PE is the systematic process of evaluating the body and its function.6 It is divided into 4 separate processes: inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation. Typically, pharmacists develop inspection skills, but are less familiar with the other processes; previous studies have suggested that pharmacists are most comfortable assessing skin, hair and nails (e.g., inspecting a dermatologic reaction) and evaluating a patient's mental status.7–8 Development of PE skills beyond inspection has the potential to allow pharmacists to augment their assessment and monitoring of drug therapy, and to increase their effectiveness in a collaborative health care team environment.

The concept of pharmacists using PE skills in practice can be traced back to the 1970s,9 but subsequent surveys have demonstrated that most pharmacists do not routinely use PE to monitor their patients.7–8 More recently, several articles have been published advocating for pharmacists to perform PE, from the perspective of both improved patient care and expanded scope of practice.10–16 In 1999, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists released a position statement recommending that pharmacists broaden their role in the primary care environment to include PE as a function of collaborative drug therapy management.13

Most Bachelor of Science in Pharmacy (BScPhm) programs in Canada do not provide formalized training in PE. Some universities have introduced entry-level Doctor of Pharmacy (ELDP) programs, and all are moving toward establishing Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) programs by 2020 to emphasize more advanced development of clinical skills. Recently, the Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada released a document on educational outcomes for ELDP programs, which recommended that graduates be able to perform and interpret PE findings.14 The Blueprint for Pharmacy, an initiative led by the Canadian Pharmacists Association, advocates for skill development among practising pharmacists to include PE,15 a recommendation that was also echoed in the Canadian Pharmacists Association position statement on developing ELDP programs.11 Until ELDP programs become the standard of pharmacy education, there is an opportunity to provide formalized PE training as part of pharmacists' professional development. This led to the establishment of an introductory session on PE for pharmacists with an interest in primary care as part of a professional development program conducted jointly by the University of Alberta and the University of Toronto.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate participant pharmacists' perceptions of performing basic PE skills (e.g., vital signs) as part of their routine assessment and monitoring of drug therapy. This study involved engaging pharmacists in 2 phases: 1) before and after the session; and 2) 4 weeks after the session. The study objectives were as follows:

To assess the proportion of participants performing PE in their practice before the session

To assess participants' confidence in performing PE before and after the session

To identify perceived barriers toward performing PE among participants

To determine whether participants had introduced or expanded the application of PE in their practice 4 weeks after the session.

Methods

Study participants

Participants in this study attended a professional development program for pharmacists organized jointly by the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Alberta and the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy at the University of Toronto, held October 24 to 27, 2010, simultaneously in Banff, Alberta, and Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada. This program was designed to promote and enhance pharmacists' knowledge and skill in primary care practice, and enrollment was open to all practising pharmacists in Canada.

A 2-hour session introducing pharmacists to selected components of PE was included as part of the program. The session combined didactic instruction with practical application, during which participants were instructed on how to perform a particular aspect of PE, and then given time to practise the skill on each other. The 2 instructors were post-BScPhm PharmD-trained pharmacists, both with formalized PE training. Although the sessions in Alberta and Ontario were conducted by different instructors, they were designed to be identical in structure and content. The session included the following topics with the aid of case examples: introduction to PE; principles of PE (inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation); measuring vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature); diabetic foot examination; and assessment of peripheral edema.

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta.

Data collection

Participants' perceptions of and knowledge about PE were assessed via a series of surveys, which were administered immediately before and after the session in a blinded fashion, and 4 weeks after the session (unblinded). The surveys were designed to ascertain participants' perception of the usefulness of PE in routine drug assessment and monitoring, and their confidence in performing PE. In addition, participants were asked to describe perceived barriers to performing PE in their practice (including possible selection from a list of 6 prespecified barriers). Participants were also invited to provide general feedback regarding the quality and content of the session.

The first survey was provided to the participants immediately prior to the start of the session (pre-session survey). All participants provided implied written consent. The pre-session survey consisted of 5 questions that used a 4-point unipolar scale designed to ascertain participants' pre-session confidence in performing PE. For each question, participants were asked to select 1 of the following responses: not confident, somewhat confident, confident or very confident.

At the end of the 2-hour session, participants were asked to complete another survey (post-session survey), which consisted of the same 5 questions as in the pre-session survey. Additionally, the post-session survey included questions exploring participants' overall evaluation of the session.

Four weeks after the session, participants were contacted (via e-mail or telephone) to determine if they had incorporated or expanded PE in their practice (4-week follow-up survey) and, if so, to provide examples.

Data analysis

Analysis of the pre- and post-session survey questions consisted of assigning each response with a numerical value: 1 = not confident, 2 = somewhat confident, 3 = confident and 4 = very confident. For each question, a weighted mean value was calculated by adding the assigned numerical values of the responses and then dividing by the total number of responses. A statistical comparison between the pre- and post-session responses was performed using an unpaired, 2-sided Student's t-test (Microsoft Excel, version 12.2.7, Redmond, Washington). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

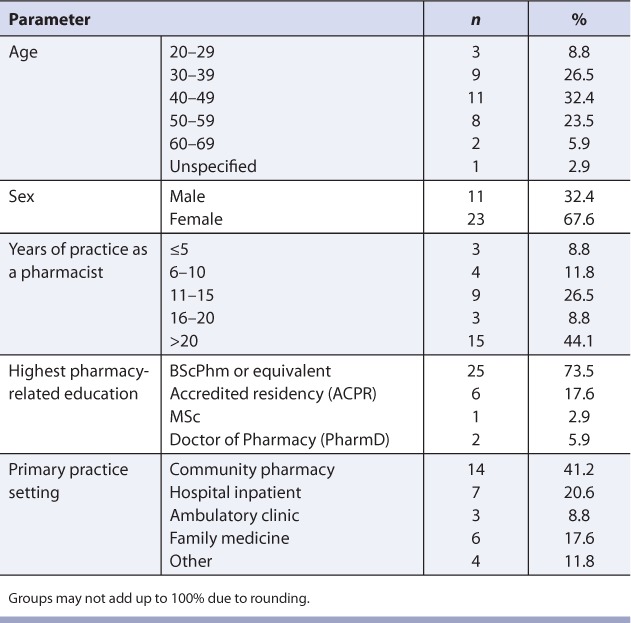

Thirty-four pharmacists participated in the study. Of the participants, 73.5% had a Bachelor of Pharmacy degree as their highest pharmacy-related education, and the rest had more advanced training (e.g., accredited residency, PharmD). Approximately two-thirds (67.6%) of the participants were female. A total of 44.1% had 20 years or more experience as a pharmacist, and 41.2% worked primarily in a community pharmacy. Other practice areas included family medicine-based practices (primary care networks and family health teams), hospitals and ambulatory clinics. The demographics of the pharmacists enrolled in the study are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographics (n = 34)

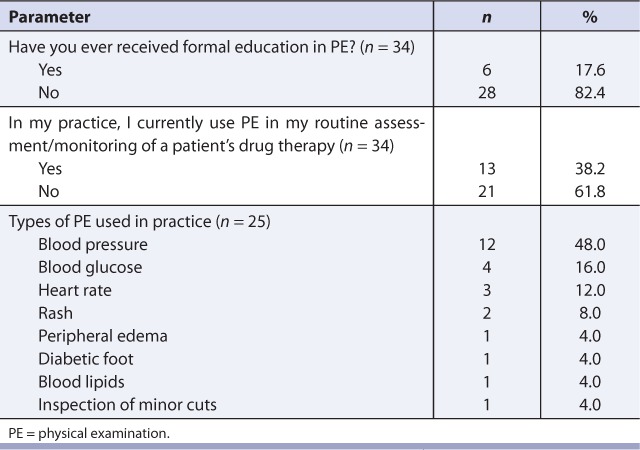

With respect to PE, 82.4% of participants stated that they had never received any type of formal PE education, but 38.2% reported that they had performed some type of PE in their practice on a routine basis, the most common being measurement of blood pressure (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Baseline assessment of PE

Of the 34 participants, 28 (82.4%) identified barriers to performing PE in their practice (Table 3). A total of 70 responses to potential barriers were identified, the most common being lack of formal education (n = 26), lack of comfort with performing PE (n = 12) and perceived patient discomfort at having a pharmacist perform PE (n = 11). Nine participants (26.5%) felt that they did not need to perform PE because they had access to PE information from other health care professionals, and 4 (11.8%) did not see the value in performing PE.

TABLE 3.

Identified barriers to PE (n = 28)

A summary of the responses to the pre- and post-session surveys is included in Figure 1. The pre-session survey demonstrated that most participants were either not confident or somewhat confident with PE. Between the pre- and post-session surveys, the weighted mean response for each question increased, with most participants responding that they felt either confident or somewhat confident at performing PE. Overall, 4 of the 5 questions demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in participant confidence between the pre- and post-session surveys. The only area that did not demonstrate statistical improvement was confidence in intervening on a patient's drug therapy based on PE findings.

FIGURE 1.

Confidence in performing physical examination: pre- and post-session survey results

No regression analysis was conducted to correlate barriers to or confidence in performing PE with different participant demographics or session instructors.

In the post-session evaluation, 97.0% of participants strongly agreed or agreed that the session improved their knowledge of PE, 87.9% strongly agreed or agreed that they would like more opportunities to learn about PE and 17.6% of the participants stated that they wished the session had been longer and/or they had more time during the session to practise. As well, 87.9% strongly agreed or agreed that the session reduced their apprehensions regarding PE. However, only 28.1% stated that they planned to use PE in practice, while 53.1% stated they possibly would and 18.8% stated they planned not to use PE. Twenty-eight of the 34 participants consented to being contacted for the 4-week follow-up survey, and 12 (42.9%) completed the survey (Table 4). Twenty-seven participants were contacted via e-mail, and 1 was contacted via telephone, in accordance with stated preferences. Participants contacted via e-mail received 2 reminders over the 4 weeks that the survey was open. The results demonstrated that all of the individuals who did not use PE in their practice prior to the survey (n = 7) stated that they had not yet incorporated it into their practice. Of the individuals who continued to use PE in their practice (n = 5), blood pressure measurement was the most common type of examination performed. Other skills included assessment of heart rate, blood glucose and edema. All respondents stated that they would attend another PE session in the future.

TABLE 4.

Follow-up survey results (n = 12)

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a session on PE designed specifically for pharmacists as part of a professional development program can improve overall confidence in performing PE. Prior to the session, 17.6% of participants had received some type of PE education. This is consistent with a previous survey of Toronto-area hospital pharmacists, in which 23% of respondents had been trained in PE.8 However, only 9% of those respondents reported that they used these skills regularly in practice; encouragingly, 38.2% of participants in our study indicated that they performed some sort of PE in their practice — primarily blood pressure measurement. After the session, there was a statistically significant improvement in participants' confidence in performing PE and discussing their findings with patients or other health care professionals, but confidence in intervening on a patient's drug therapy based on PE findings did not change. One explanation for this finding might be that while participants' confidence in performing PE improved during the session, they were still hesitant about acting on their findings. At the end of the session, only 28.1% of participants stated that they planned to use PE in their practice. This is lower than the pre-session reported use of 38.2%. We believe this may be due to interpretation that the question was referring to the use of new PE skills. Therefore, we believe that 28.1% of participants planned to use new PE skills in their practice after the session. Due to the low enrollment and preliminary design of the study, no regression analysis was performed using participant demographics. The results of the 4-week follow-up survey demonstrated that an educational session on PE did not result in short-term practice change.

Overall, 82.4% of participants identified barriers to performing PE in practice, the majority of which were modifiable with increased knowledge and experience. The most common barrier identified was lack of formal education. Promisingly, the primary goal of this session was to address this barrier, and 87.9% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the session addressed their apprehensions regarding PE. Other common barriers identified included lack of comfort associated with PE, either on the part of the pharmacist or the patient (as perceived by the pharmacist). Participants' discomfort with PE likely extends from lack of familiarity, which should improve with practice. From experience, we believe that patients are receptive to PE performed by any member of the health care team, if that individual explains the purpose of the examination and ensures that the patient is comfortable.

This study has several limitations that restrict its generalizability. The primary limitation is the design of the session, which was short in duration and consisted of a small group of participants. As well, participants varied greatly in their training, experience and practice settings, and were self-selected to participate in the primary care program and the evaluation study. It is likely the low uptake of PE in practice is related to the limited amount of time participants were given to practice skills during the session, and the short 4-week follow-up. Additionally, the follow-up survey had a lower-than-expected response rate, which may be due to the survey method chosen. Twenty-seven of the 28 participants who agreed to the follow-up survey preferred to be contacted via e-mail rather than by telephone, and this method demands less commitment on the part of respondents. Potential future research questions include a more rigorous assessment of pharmacists' perception of the role of PE in routine monitoring and assessment of drug therapy with regard to different practice settings (e.g., community vs hospital), and identifying and addressing the specific barriers to performing PE in practice. Future research should also include longer follow-up to ensure that pharmacist- and practice setting–specific barriers were addressed.

Conclusion

The evolving practice of clinical pharmacy has created a need and opportunity for pharmacists to develop skills traditionally performed by other members of the health care team, such as PE. This evolution brought about the development and delivery of a session to teach PE skills to pharmacists as part of a primary care professional development program. Prior to the session, most participants did not use PE in practice, primarily due to lack of formal training. While the session improved participants' confidence in performing PE and discussing their findings with other health care team members and patients, it did not improve their confidence to change drug therapy based on PE findings. This study demonstrates that a session designed specifically to teach PE skills to pharmacists can improve confidence in performing PE and address self-identified barriers to implementing PE in practice. Although the session did not result in short-term improved use of PE in practice, all 12 follow-up participants stated that they would attend another session on PE in the future.

References

- 1.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:816–7. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.College of Pharmacists of British Columbia. Vancouver (BC): College of Pharmacists of British Columbia; 2008. Professional practice policy 58: medication management (adapting a prescription) Available: www.bcpharmacists.org/library/A-About_Us/A-2_Governance/5003-PGP-PPP58.pdf (accessed April 18, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists. Halifax (NS): Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists; 2011. Standards of practice: prescribing of drugs by pharmacists. Available: www.nspharmacists.ca/standards/prescribing-of-drugs-by-pharmacists.html (accessed April 18, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberta College of Pharmacists. Edmonton (AB): Alberta College of Pharmacists; 2007. Standards of practice. Available: pharmacists.ab.ca/Content_Files/Files/HPA_Standards_FINAL.pdf (accessed April 18, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sketris I. Extending prescribing privileges in Canada. Can Pharm J. 2009;142:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG, editors. Bates' guide to physical examination and history taking. 10th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. Overview: physical examination and history taking; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamcik BA, Stimmel GL. Use of physical assessment skills by clinical pharmacists in monitoring drug therapy response: attitudes and frequency. Am J Pharm Educ. 1989;53:127–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nabzdyk K. Hospital pharmacists' use of physical assessment: attitudes and frequency. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1997;50:177–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longe RL, Cavert JC. Physical assessment and the clinical pharmacist. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1977;11:200–3. doi: 10.1177/106002807701100401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson SH. Should pharmacists perform physical assessments? The “pro” side. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2007;60:271–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Pharmacists Association. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2011. CPhA position statement on a doctor of pharmacy degree as an entry-level to practice. Available: www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-onthe-issues/PPDoctorOfPharmacyEN.pdf (accessed April 18, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson SH, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, et al. Effect of adding pharmacists to primary care teams on blood pressure control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:20–6. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASH P statement on the pharmacist's role in primary care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1665–7. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.16.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada. Edmonton (AB): Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada; 2010. AFPC educational outcomes for first degree professional degree programs in pharmacy (entry-to-practice pharmacy programs) in Canada. Available: www.afpc.info/content.php?SectionID=4&ContentID=21&Language=en (accessed April 18, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canadian Pharmacists Association. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2011. The blueprint for pharmacy: the vision for pharmacy. Available: www.blueprintforpharmacy.ca/about (accessed April 18, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barry AR, Pearson GJ. Making hospital pharmacists indispensible on the healthcare team: revolution in waiting. J Pharm Pract Res. 2009;39:256–7. [Google Scholar]