Introduction

Rapid changes in health care and the evolving role of the pharmacist, as shown by the recent expanding scope of practice changes in several Canadian jurisdictions, have created a need for additional pharmacist continuing education (CE). Many pharmacists move into these new roles with excitement and trepidation. Some pharmacists may be comfortable communicating with patients but less certain how to document the care provided or how to conduct physical assessments. Some may have had plenty of opportunities to talk with physicians but less experience working with other health care providers. Many know that these new roles will improve patient care and want support and CE to move confidently into this new world.

KEY POINTS.

Pharmacists want support and continuing education (CE) opportunities to move confidently into new roles.

Partnership between primary health care pharmacists, professional associations and universities creates high-quality CE programming.

Distance education best practices should inform course design and operation.

A multi-faceted evaluation framework and soliciting learner feedback contributes to making an already good course even better.

POINTS CLÉS.

Les pharmaciens veulent du soutien et des programmes de formation continue pour se préparer avec confiance à leurs nouveau rôles.

Le partenariat entre les pharmaciens prestataires de soins de santé primaires, les associations professionnelles et les universités favorise la création de programmes de formation continue de haute qualité.

La conception et la prestation des cours devraient s'appuyer sur des pratiques exemplaires en matière d'éducation à distance.

Un cadre d'évaluation à volets multiples et la collecte de la rétroaction des apprenants contribuent à l'amélioration d'un cours qui est déjà bon.

A group of pharmacists involved in the Primary Care Pharmacy Specialty Network (PC-PSN), a joint initiative of the Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA) and the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists (CSHP), could see that these changes were beginning to happen within the practices of PC-PSN members and through research initiatives such as IMPACT,1–3 SCRIP, SCRIP-plus and REACT.4–6 The group envisioned a “real-world,” accessible, national CE program that would enable pharmacists to enhance patient care in primary health care settings.

This article describes the creation, pilot testing and launch of the Adapting Pharmacists' Skills and Approaches to Maximize Patients' Drug Therapy Effectiveness (ADAPT) CE program. The program comprises 7 online learning modules designed to enhance patient care and collaborative skills, plus a face-to-face workshop designed to provide additional feedback about those skills. Program development began in November 2009. The pilot offering of the program occurred from August 2010 to February 2011 and the program became available to all Canadian pharmacists in August 2011 (www.pharmacists.ca/adapt).

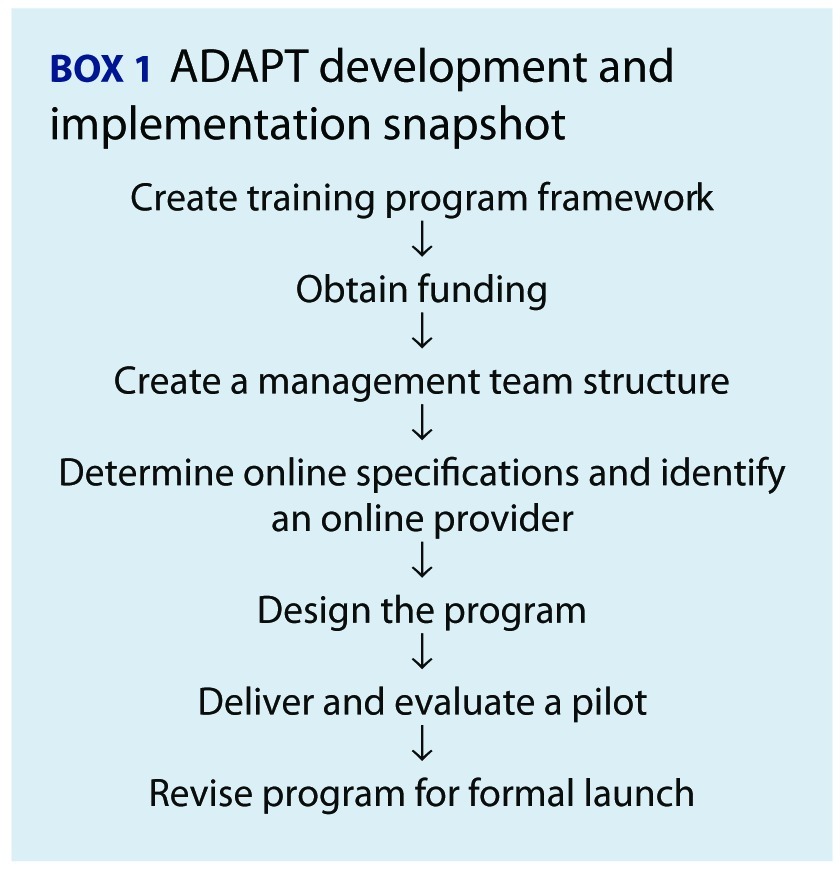

It was a challenge to create a rigorous, high-quality program for working pharmacists that was practical in terms of the skills taught and the delivery method. A summary of the ADAPT development and implementation process is provided in Box 1. Lessons learned from the ADAPT experience may help others to develop similar CE programs in the future.

|

Creating the training program framework

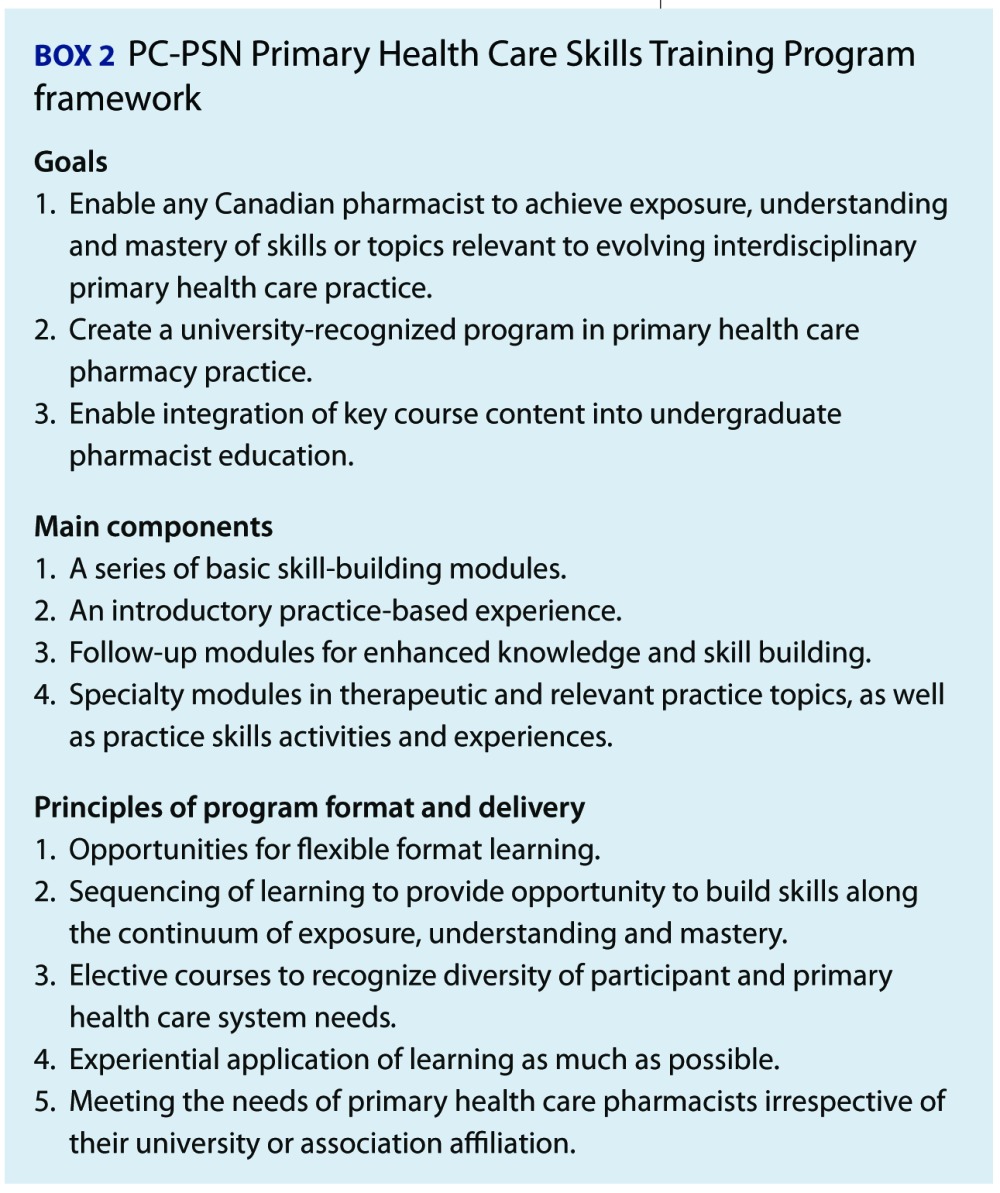

In 2007, a PC-PSN training subcommittee created a Primary Health Care Skills Training Program framework (Box 2) using content and structure developed for the IMPACT (Integrating Family Medicine and Pharmacy to Advance Primary Care Therapeutics) project.7

|

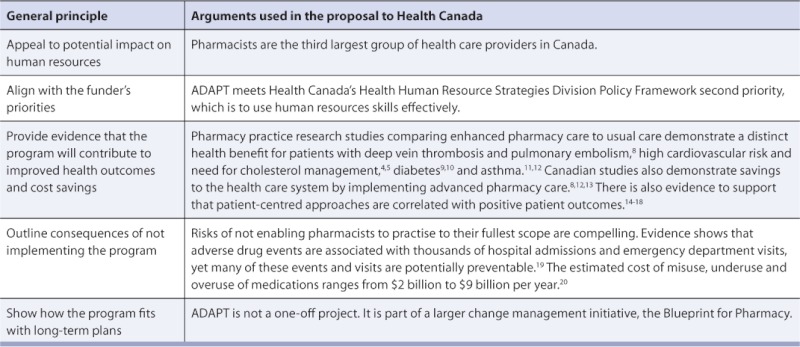

Obtaining funding: Creating your luck

The initial challenge was obtaining funding to create a high-quality CE program. A development grant provided by the McMaster University Department of Family Medicine supported the proposal development and networking with potential funders. Several meetings were held with representatives from faculties of pharmacy and pharmaceutical companies before the Health Canada opportunity, facilitated by CPhA, presented itself. In July 2009, CPhA worked with the PC-PSN on a $500,000 funding proposal to Health Canada's Health Care Policy Contribution Program to create a CE program for primary health care pharmacists using the arguments outlined in Table 1. CPhA, CSHP and PC-PSN representatives entered into a partnership for the purpose of this proposal. Notice of successful funding was received in November 2009.

TABLE 1.

Arguments for funding ADAPT program development and evaluation

Lesson learned:

Ensure adequate unrestricted funding. Health Canada's funding made it possible to assemble the right pharmacists, educators, researchers and project managers to deliver and evaluate a mixed model of online, real-world and in-person CE that is not biased toward a particular product, manufacturer or practice setting.

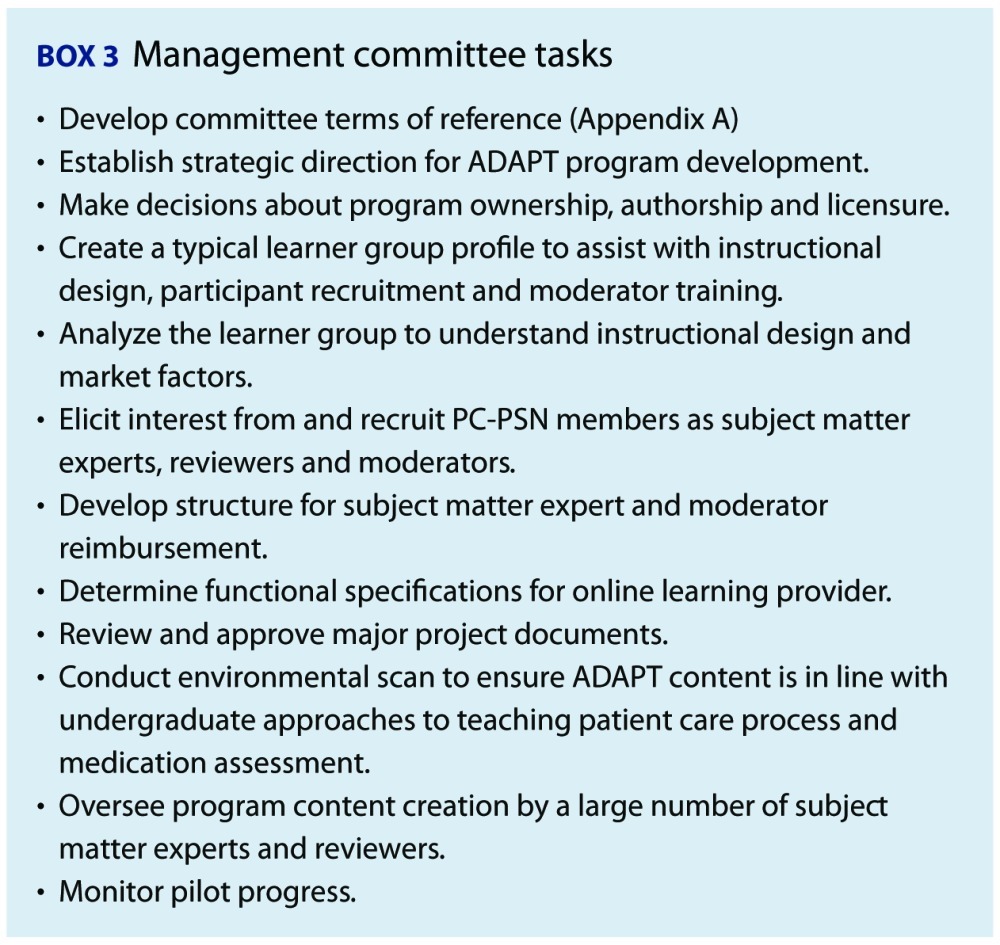

Managing development and implementation

Managing this project on a tight timeline required strong project management skills and a collaborative working environment. This was achieved by hiring a project manager who coordinated many components and managed multiple partners and by creating a management committee (492.6KB, pdf) comprised of representatives from the PC-PSN, CPhA and CSHP and jointly chaired by a CPhA staff member and PC-PSN representative. The management committee met by monthly teleconference and quarterly face-to-face or Web-facilitated meetings; co-chairs met weekly with the project manager. They also used a secured online data-sharing website (PBWiki) to facilitate communications among committee members and their respective organizations. Tasks of the management committee are outlined in Box 3.

|

The management committee contributed significantly to further developing the ADAPT program framework. For example, the committee's distance learning experts identified the benefits of using online moderators to support ADAPT learners. The management committee also responded quickly to address learner challenges that arose during the pilot.

Lessons learned:

Work with partner associations. ADAPT benefited from the collaborative working relationships among team members and the willingness and enthusiasm of CPhA and CSHP to support their joint PC-PSN to undertake a new kind of partnership to develop this innovative program.

Use principles of collaboration. A clear management committee structure and communication plan facilitated decision-making, conflict resolution and task completion to ensure that the project was completed on time, within budget and was of high quality.

Educational program development is a fluid process. An adaptive, creative and dedicated management committee arrives at key decisions by revising initial assumptions as new data emerge.

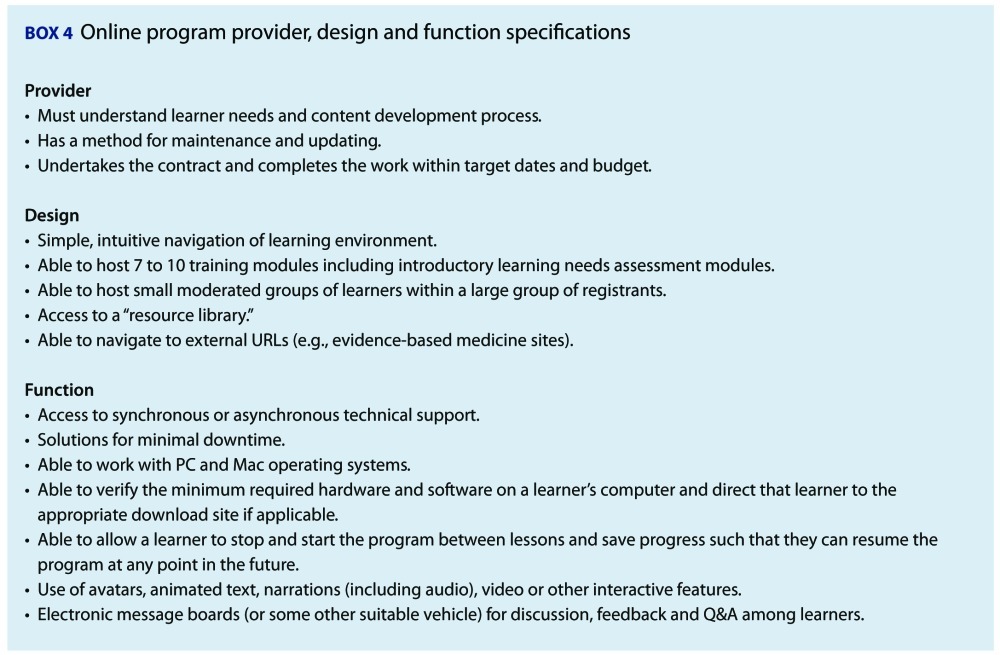

Identifying an e-learning provider

Criteria for selection of an online learning environment (e-learning platform) and service provider (design, building, hosting and maintenance) for the online program were identified. Guiding principles included that the learning environment be interactive, multimodal in its learning methods and contemporary in its layout. Platform requirements were defined prior to the request for proposal process. An evaluation of the 3 bidders included site visits by ADAPT principals and use of an objective bid evaluation tool based on the criteria specified in Box 4. The Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo, was selected as the ADAPT e-learning provider.

|

Lessons learned:

Use distance education expertise. Our management committee experts helped us to define “need to have” versus “nice to have” features of a distance learning environment and provider, keeping the learners' needs foremost and staying on time and on budget.

Use distance education best practices. We selected the provider before preparing the educational content and this enabled maximal use of the provider's education experts who guided development of the content to fit the learning environment capabilities.

Designing the ADAPT program

Two teams were involved in designing the main components of the ADAPT program. Centre for Extended Learning education experts at the University of Waterloo worked closely with subject matter experts to develop online module learning objectives, content and activities. A second team, with expertise from the University of Toronto Standardized Patient Program (http://spp.utoronto.ca/), developed objectives, activities and assessment tools for the face-to-face component of ADAPT.

Online module development

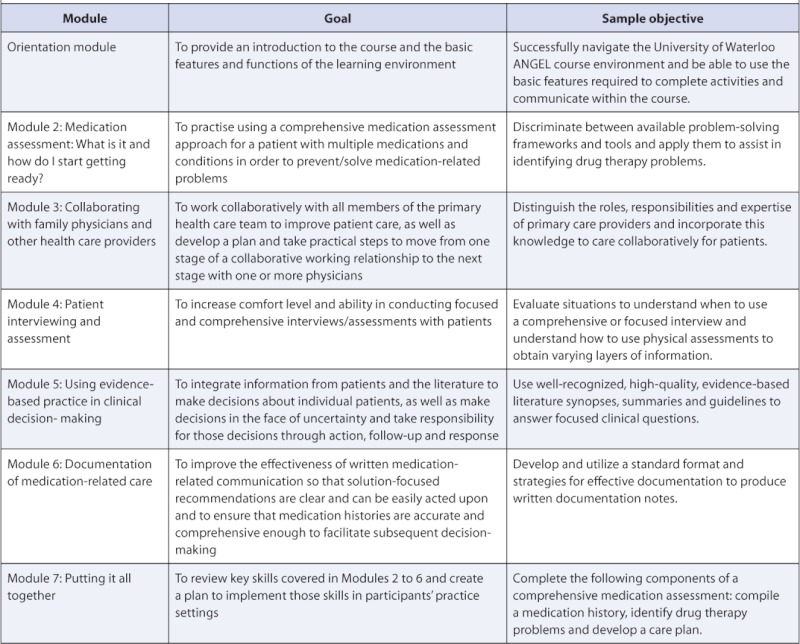

The goals, as well as a sample learning objective for each of the ADAPT modules, are outlined in Table 2. Learners completed each module's activities (e.g., lectures, videos, exercises) within a 1–3 week timeframe and also participated several times a week in discussion boards. Further information about the individual modules can be found at www.pharmacists.ca/adapt.

TABLE 2.

ADAPT module descriptions

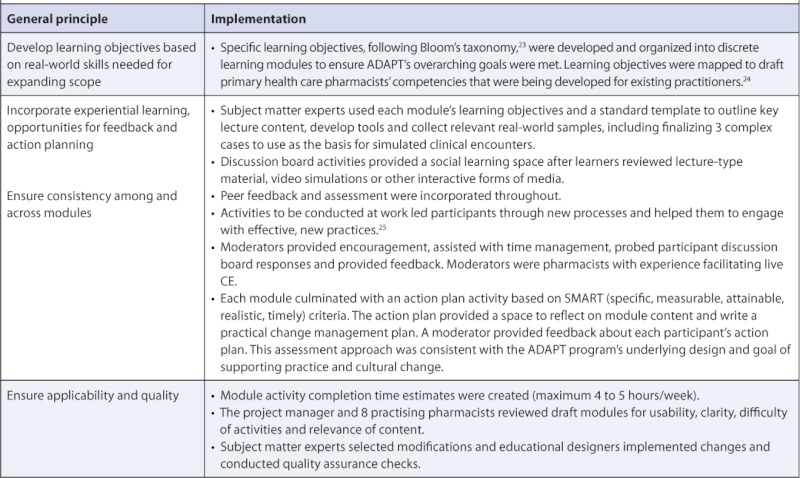

For ADAPT to enable practice change, we used an experiential learning approach with many interaction opportunities for learners. The principles of cognitive apprenticeship informed the program design. In this model, the learner engages in authentic (i.e., real world) activities under the guidance of experts whose involvement diminishes over time as learners gain competency.21 This represented a significant departure from traditional approaches in pharmacist distance CE programs, where learning is a passive, individual activity and evaluation is based on simple quizzes. 22 Table 3 outlines the general principles that informed ADAPT's design and how these principles were implemented during development.

TABLE 3.

Steps in ADAPT development

At the time the pilot orientation module was “live,” only the first 3 content modules were completed (with the fourth in draft). This gave subject matter experts and educational designers an opportunity to improve the modules still in production based on lessons learned from earlier modules. For moderators, important iterative improvements included more explicit support documents and development of an action plan feedback tool that simplified the process of providing participants with meaningful responses.

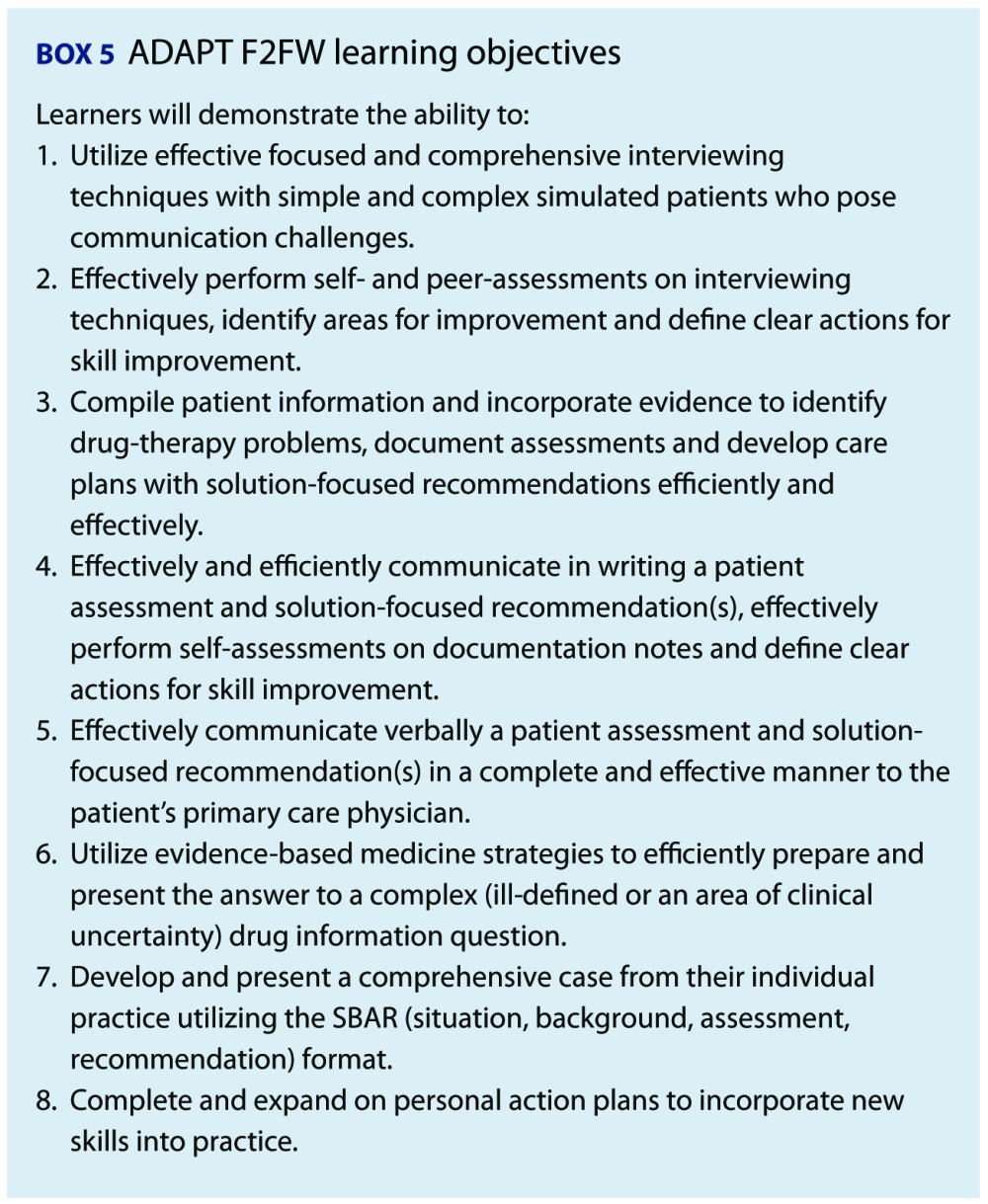

Face-to-face development

The 1-day face-to-face workshop (F2FW) development began while the online modules were in progress. The purpose of the F2FW was to further transform skills acquired during the online component into practice. The learning objectives are outlined in Box 5.

|

The activities selected for the F2FW included patient interviewing, medication assessment, documentation, drug information retrieval and communication, and patient case discussion with a physician. The F2FW included direct interaction with standardized patients — a commonly used approach in undergraduate pharmacy education and entry-to-practice pharmacy examinations and more recently in pharmacy CE.26,27 Four patient clinical scenarios were developed and used to train standardized patients. Physician interactions were incorporated to assist learners who may lack the opportunity to gain confidence in communicating with physicians about therapeutic choices and patient management. Timely verbal and written feedback about interviewing skills from the standardized patients, physicians, peers and group facilitators was incorporated using standardized global rating scales.28–31 Presentations of cases from their own practices to peers, as well as discussion of ADAPT action plan progress, were also incorporated. To make the most efficient use of time and budget, the F2FW was designed to allow learners to rotate through activities in groups of 4, taking turns interviewing patients, providing feedback and communicating with physicians. The F2FW took place 1 to 2 months after completion of all online modules.

Lessons learned:

Be innovative with educational design. The development of ADAPT had an overarching plan that was grounded in the educational theory felt to best help pharmacists develop change management strategies. Innovation in Canadian pharmacy education included learning objectives linked directly to desired competencies, requirement for weekly (often daily) learner commitment to practice activities, use of online moderators and peer discussion boards, requirement for learner reflection and active development of a change management plan, inclusion of a F2FW to allow for structured practice and assessment of skills and the extended length of the program that allowed for skill development beyond simple knowledge acquisition.

Use a systematic process for development. The systematic process of developing learning objectives based on required competencies followed by creation of content and activities that related specifically to those learning objectives allowed us to ensure that each program component was relevant to patient care.

Plan for the future. To support the possibility that future iterations of ADAPT could lead to a certificate or credential, a performance-based evaluation of the skills taught in the program was incorporated to enable learners to demonstrate attainment of learning objectives and relevant competencies.

Implementation: Planning for success

In addition to developing ADAPT based on sound educational principles and quality design, the management committee felt that there were 2 key steps to planning for a successful CE program that would facilitate practice change:

Conduct a pilot, purposefully selecting participants to represent a range of practice settings, demographics and geography.

Evaluate the program rigorously so that course content, delivery and facilitation processes could be revised and improved using an evidence-informed approach.

The pilot

CPhA, CSHP and PC-PSN member pharmacists received an invitation to participate in a pilot of the ADAPT program in spring 2010. Interested pharmacists completed an online open-access module that provided background about primary health care reform, pharmacists' evolving roles and information about the expectations of the ADAPT program. Pharmacists (n = 271) who registered upon completion of the initial open-access module and who agreed to participate in the pilot and associated program evaluation were candidates for the pilot group (n = 90). Selection criteria included practice setting (focus on community pharmacy but with varied practice sites represented), wide geographic representation and capacity to dedicate significant time to ADAPT. Participants were divided into 5 cohorts and a moderator was assigned to each cohort. The online modules started in September 2010 and finished in December 2010. A 1-day F2FW was made available in Saskatoon and Waterloo in February 2011.

Lesson learned:

Include willing pilot participants. These pharmacists not only came to learn but were willing to deliver constructive feedback, knowing that their de-identified assignments, comments and discussions were being analyzed to better understand the learning that was occurring.

The evaluation

The $50,000 evaluation budget for the ADAPT program was contracted to the Élisabeth Bruyère Research Institute who coordinated with co-investigators from other universities. The evaluation was designed to provide insight into how the participants fared in the pilot program, improvements that could be made and how participants made transformational change within their own practice. Initial evaluation results32–40 have been presented (full publication pending), including examination of the demographics and motivation of learners, evaluation of the learner experience, satisfaction and participation, course assessment and impact on performance of skills and practice change.

Lesson learned:

Conduct a pilot and evaluate it. Feedback from the evaluation of the pilot has been instrumental in modifying the program to ensure sustainability and application to practice.

Conclusion

This article describes the creation of the ADAPT CE program. We set out to create an online and F2FW CE program that could improve patient care and collaborative skill development and enable practice change. We worked closely with partner associations, developed a strong unrestricted funding proposal, used principles of collaboration in project management, used educational approaches that could enable practice change, selected an e-learning provider who met our requirements, systematically developed content, put supports in place to plan for the future and conducted and evaluated a pilot with willing participants. The lessons learned are summarized in Box 6. Each of these steps was vital to the successful implementation of the ADAPT program. We believe that the program represents something very new for Canadian pharmacists and pharmacy educators to consider. Lessons learned may help inform the development of future CE programs for practising pharmacists.

|

Final lesson learned:

Be passionate about the work. The ADAPT program was developed, delivered and evaluated over a 14-month period. The program team accomplished this work by motivating each other and holding a common passion for making a contribution to fostering successful pharmacy practice in Canada.

Future directions

The ADAPT pilot concluded in February 2011. As anticipated, the pilot yielded significant input from its participants that has guided modifications implemented prior to the formal launch of the program in August 2011.

The ADAPT program online foundational modules and F2FW, which address the first 2 main components of the PC-PSN Primary Health Care Skills Training Program framework, offer a strong foundation for pharmacists to orient their practice toward delivering optimal patient-centred care. It seems reasonable to propose that additional modules will be created to build on this foundation in the future, addressing additional practice skills and pharmacotherapeutic knowledge.

Steps to address the second and third overarching goals of the PC-PSN (see Box 2), to create a university-recognized program and to enable integration of key course content into undergraduate pharmacist education, are in progress. A national ADAPT advisory committee, with representation from the management committee and other stakeholders, has been established to guide this work.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the important contributions of Heather Mohr, ADAPT project manager, in bringing this program to fruition. Many people contributed to the development of this program; their commitment and hard work is truly appreciated by all involved. The Canadian Pharmacists Association's (CPhA) ADAPT program was developed in collaboration with the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists (CSHP) and the members of the CPhA-CSHP Primary Care Pharmacy Specialty Network. ADAPT is funded in part by Health Canada under the Health Care Policy Contribution Program.

References

- 1.Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J, et al. Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primary care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:913–17. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrell B, Pottie K, Haydt S, Kennie N, Sellors C, Dolovich L. Integrating into family practice: the experiences of pharmacists in Ontario, Canada. Int J Pharm Pract. 2008;16:309–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrell F, Dolovich L, Austin Z, Sellors C. Implementing a mentorship program for pharmacists integrating into family practice: practical experience from the IMPACT project team. Can Pharm J. 2010;143:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA, Teo KK, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of community pharmacist intervention on cholesterol risk management: the Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP) Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1149–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuyuki RT, Olson KL, Dubyk AM, et al. Effect of community pharmacist intervention on cholesterol levels in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events: the Second Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP-plus) Am J Med. 2004;116:130–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuyuki R, Fradette M, Johnson J, et al. A multicenter disease management program for hospitalized patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10:473–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin Z, Dolovich L, Lau E, et al. Teaching and assessing primary care skills in pharmacy: the family practice simulator model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69:500–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zed PJ, Filiatrault L. Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction of a pharmacist-managed, emergency department-based outpatient treatment program for venous thromboembolic disease. CJEM. 2008;10:10–17. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500009957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, Einarson TR. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part I: systematic review and meta-analysis in diabetes management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1569–82. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson SH, Johnson JA, Biggs RS, Tsuyuki RT. Greater effect of enhanced pharmacist care on cholesterol management in patients with diabetes mellitus: a planned subgroup analysis of the Study of Cardiovascular Risk Intervention by Pharmacists (SCRIP) Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:389–94. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.4.389.33169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diamond SA, Chapman KR. The impact of a nationally coordinated pharmacy-based asthma education intervention. Can Respir J. 2001;8:261–65. doi: 10.1155/2001/380485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLean W, Gillis J, Waller R. The BC Community Pharmacy Asthma Study: a study of clinical, economic and holistic outcomes influenced by an asthma care protocol provided by specially trained community pharmacists in British Columbia. Can Respir J. 2003;10:195–202. doi: 10.1155/2003/736042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kephart G, Sketris IS, Bowles SK, et al. Impact of a criteriabased reimbursement policy on the use of respiratory drugs delivered by nebulizer and health care services utilization in Nova Scotia, Canada. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1248–57. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.9.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alamo MM, Moral RR, Perula de Torres LA. Evaluation of a patient-centred approach in generalized musculoskeletal chronic pain/fibromyalgia patients in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulware LE, Daumit GL, Frick KD, et al. An evidencebased review of patient-centered behavioral interventions for hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:221–32. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molzahn AE, Hibbert MP, Gaudet D, et al. Managing chronic kidney disease in a nurse-run, physician-monitored clinic: the CanPREVENT experience. Can J Nurs Res. 2008;40:96–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel P, Zed PJ. Drug-related visits to the emergency department: how big is the problem? Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:915–23. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.11.915.33630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romanow R. Ottawa(ON): National Library of Canada, Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada — Final report. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins A, Hawkins J, Carver SM. A cognitive apprenticeship for disadvantaged students. In: Means B, Chelemer C, Knapp MS, editors. Teaching advanced skills to students at risk. San Franciso (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1991. pp. 216–43. p. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J, Seller W. Curriculum perspectives and practice. Toronto (ON): Copp Clark Pitman Ltd.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloom B. Taxonomy of educational objectives. Handbook I: the cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Co, Inc.; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennie N, Farrell B, Ward N, et al. Pharmacists' provision of primary health care: a modified Delphi validation of pharmacists competencies. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliver K. 1999. Situated cognition and cognitive apprenticeships. Available: www.edtech.vt.edu/edtech/id/models/powerpoint/cog.pdf (accessed May 23, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin Z, O'Byrne C, Pugsley J, Munoz L. Development and validation processes for an OSCE for entry-to-practice certification in pharmacy: the Canadian experience. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(3) Article 76. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau E, Dolovich L, Austin Z. Comparison of self, physician and simulated patient ratings of pharmacist performance in a family practice simulator. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:129–40. doi: 10.1080/13561820601133981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodges B, Regehr G, Hanson M, McNaughton N. Validation of an objective structured clinical examination in psychiatry. Acad Med. 1998;73:910–12. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199808000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regehr G, MacRae H, Reznick RK, Szalay D. Comparing the psychometric properties of checklists and global rating scales for assessing performance on an OSCE-format examination. Acad Med. 1998;73:993–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regehr G, Freeman R, Hodges B, Russell L. Assessing the generalizability of OSCE measures across content domains. Acad Med. 1999;74:1320–2. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199912000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reznick RK, Regehr G, Yee G, et al. Process-rating forms versus task-specific checklists in an OSCE for medical licensure. Medical Council of Canada. Acad Med. 1998;73(10 Suppl):S97–S99. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199810000-00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrell B, Ward N, Dolovich L, et al. The who's who of the pilot ADAPT program (abstract) Can Pharm J. 2011;144(5):e1. Available: www.cpjournal.ca/doi/pdf/10.3821/1913-701X-144.5.e1 (accessed June 15, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrell B, Ward N, Kennie N, et al. 2011. Learning how to work interprofesionally: the experience of pharmacists undertaking an online and experiential skills development program. North American Primary Care Research Group Conference, Banff, Alberta, November 15, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrell B, Ward N, Kennie N, et al. Learner satisfaction and course assessment of the pilot ADAPT program. Can Pharm J. 2011;144(5):e3. Available: www.cpjournal.ca/doi/pdf/10.3821/1913-701X-144.5.e1 (accessed June 15, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jennings B, Farrell B. 2011. Effective practices for developing e-learning programs and technologies. University Professional and Continuing Education Association Annual Conference, Toronto, Ontario, April 7, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones C, Farrell B, Gubbels A, et al. Evaluation of factors affecting participation in the pilot ADAPT program (poster) Can Pharm J. 2011;144(5):e30. Available: www.cpjournal.ca/doi/pdf/10.3821/1913-701X-144.5.e1 (accessed June 15, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorgensen D, Gubbels A, Farrell B, et al. Characteristics of pharmacists who enrolled in the pilot ADAPT education program: implications for practice change. Can Pharm J. 2012:145. doi: 10.3821/145.6.cpj260. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorgenson D, Farrell B, Tabak D, et al. Evaluation of the pilot ADAPT face-to-face workshop (poster) Can Pharm J. 2011;144(5):e28. Available: www.cpjournal.ca/doi/pdf/10.3821/1913-701X-144.5.e1 (accessed June 15, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marks P, Jennings B, Waite N, et al. 2011. Towards methodological rigor in qualitative research: a case study (poster) Opportunities and New Directions Teaching and Learning Research Conference, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, April 27–28, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward N, Farrell B, Jennings B, et al. Evaluation of the learner experience in the pilot ADAPT program (abstract) Can Pharm J. 2011;144(5):e2. Available: www.cpjournal.ca/doi/pdf/10.3821/1913-701X-144.5.e1 (accessed June 15, 2012) [Google Scholar]