Abstract

RIG-I is a cytosolic multi-domain protein that detects viral RNA and elicits an antiviral immune response. Two N-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARDs) transmit the signal and the regulatory domain prevents signaling in the absence of viral RNA. 5′-triphosphate and double stranded (ds) RNA are two molecular patterns that enable RIG-I to discriminate pathogenic from self-RNA. However, the function of the ATPase domain that is also required for activity is less clear. Using single-molecule fluorescence assays we discovered a robust, ATP-powered dsRNA translocation activity of RIG-I. The CARDs dramatically suppress translocation in the absence of 5′f-triphosphate and the activation by 5′-triphosphate triggers RIG-I to translocate preferentially on dsRNA in cis. This functional integration of two RNA molecular patterns may provide a means to specifically sense and counteract replicating viruses.

RIG-I is a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor that senses pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on viral RNA and triggers an antiviral immune response by activating type-I interferons (IFN-α/β) (1). A 5′-triphosphate moiety on viral RNA is a major PAMP detected by RIG-I as a viral signature (2, 3). 5′-triphosphates arise during viral replication and are absent in most cytosolic RNA due to cleavage or capping modifications (4–6). Another PAMP for RIG-I is double-stranded (ds) RNA, although it is less effective than 5′-triphosphate (1, 7–13). It remains unclear, however, whether these distinct patterns trigger RIG-I signaling independently, or whether they are integrated by RIG-I to increase specificity for viral RNA. RIG-I is composed of two N-terminal tandem CARDs (caspase activation and recruitment domain), a central DExH box RNA helicase/ATPase domain, and a C-terminal regulatory domain (RD). The CARDs are ubiquitinated by TRIM25 (14) and the ubiquitinated CARDs interact with the CARD on MAVS (also called IPS-1, Cardif or VISA) on the mitochondrial outer membrane to elicit downstream signaling that leads to IFN expression (15–18). The C-terminal RD inhibits RIG-I signaling in the absence of viral RNA (8) and senses the 5′-triphosphate to guide RIG-I to bind viral RNA with high specificity (19, 20). While the role of CARDs and RD has been characterized, the function of the ATPase domain remains elusive (21). A single point mutation (K270A) in the ATPase site rendered RIG-I inactive in antiviral signaling (1) even though it retained RNA binding ability (22). Furthermore, the ATPase activity of RIG-I correlates closely with the dsRNA-induced RIG-I signaling (13). However, it is unknown why the ATPase activity is required for RIG-I function.

RNA/DNA helicases usually unwind duplex nucleic acids by translocating on one of the product single strands using ATP hydrolysis and their ATPase activity is consequently stimulated by single stranded (ss) nucleic acids. In contrast, the ATPase activity of RIG-I is stimulated by dsRNA (19). We therefore examined whether RIG-I uses ATP hydrolysis to translocate on dsRNA. The dsRNA was made by annealing two complementary 25mer ssRNAs, one labeled with 3′-biotin and the other with a 3′-fluorescent label, DY547. The dsRNA was tethered to a polymer-passivated quartz surface coated with neutravidin (Fig. 1A). The activity of RIG-I was monitored by a method termed protein induced fluorescence enhancement (PIFE) which we found to be an effective alternative to fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (23, 24). The method monitors changes in intensity of a single fluorophore that correlates with proximity of the unlabeled protein (more details and comparison of PIFE and FRET data for Rep helicase translocation are given in fig. S1). PIFE can be used to study nucleic acids motors without fluorescent modification and even with high dissociation constant, which would prohibit single molecule analysis of labeled proteins.

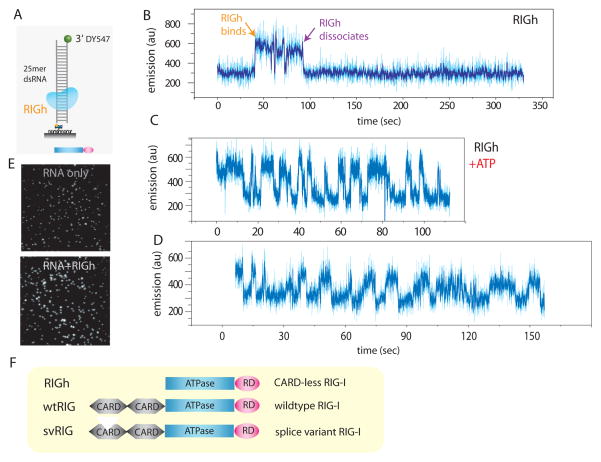

Fig. 1. PIFE visualization of RIG-I binding and translocation.

A. dsRNA (25mer) with single fluorophore (DY547) was tethered to surface via biotin-neutravidin. B. Addition of RIGh (CARD-less mutant) resulted in an abrupt increase in emission of the fluorophore, indicating RIGh binding due to PIFE (protein induced fluorescence enhancement). C, D. Addition of RIGh with ATP induced periodic fluctuation of fluorophore. E. The effect of PIFE is visible on the single molecule imaging surface i.e. fluorescence become substantially brighter upon adding RIGh protein. F. Schematic representation of three RIG-I variants used in this study; wtRIG (RIG-I wild type), RIGh (CARD-less RIG-I) and svRIG (RIG-I splice variant) is shown.

We first tested a RIG-I truncation mutant that lacks both of the CARDs, termed RIGh, because its ATPase activity is efficiently stimulated by dsRNA without the need for 5′-triphosphate on RNA (19). Binding of RIGh to dsRNA was visualized as an abrupt rise in the fluorescent signal of a single DY547 after addition of protein (Fig. 1B). Most molecules (>90%) displayed a steady binding for 20–30 sec, resulting in a strong fluorescence signal (Fig. 1E). Equilibrium binding constant calculated from single molecule binding data collected from several hundred molecules closely matched those determined using fluorescence anisotropy in bulk solution (fig S2). When ATP was added together with RIGh, we detected a periodic fluorescence fluctuation, indicative of a repetitive translocational movement (Fig. 1C, D, data obtained at 23°C). Translocation here is defined as directed movement of RIG-I along the axis of dsRNA without unwinding it. Under our conditions, RIG-I does not unwind dsRNA (fig. S3).

At 37°C, RIGh-induced fluctuation of DY547 signal became more rapid (Fig. 2A). The time interval between successive intensity peaks, denoted by Δt, was determined from many molecules of RIGh translocating on 25 bp and 40 bp dsRNA, and the resulting histograms show a single narrow peak with a longer average value for the longer dsRNA (2.9 s for 40 bp and 1.1 s for 25 bp) (Fig. 2B). When 100nM wild type RIG-I (wtRIG) was added with 1 mM ATP, the fluorescence signal also showed a gradual fluctuation at regular intervals but at a much-reduced frequency compared to RIGh (Fig. 2C). Δt histograms are peaked at longer times for 40 bp compared to 25 bp dsRNA (32.6 s vs. 18.5 s), and their average values are 15 times higher than those of RIGh (Fig. 2D).

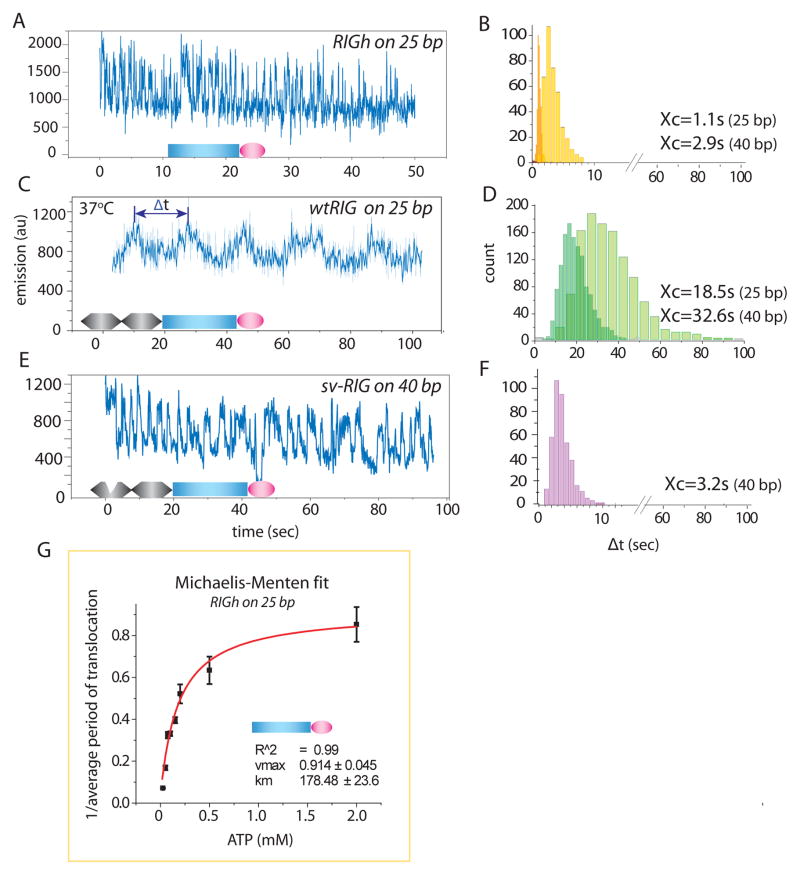

Fig. 2. RIG-I translocates on dsRNA and CARD is inhibitory.

A, C, E. 100nM RIGh (CARD-less mutant), wtRIG (RIG-I wild type) and svRIG (splice variant RIG-I) was added with 1mM ATP respectively at 37°C. The signal fluctuation represents RIG-I movement along dsRNA substrate. B, D, F. Dwell time analysis of periods denoted by Δt with a double-arrow (C) was measured for many molecules and plotted as histograms for RIGh (B), wtRIG (D) and svRIG (F) for 25bp and 40bp dsRNA. G. The inverse of average Δt, (tavg)−1, was plotted against [ATP] axis and fitted to Michaelis-Menten equation. The error bars denote standard deviation from three separate experiments each. The Vmax and Km values were 0.91 and 179μM respectively.

To test the role of ATP in the translocation reaction, the average of Δt, tavg, was determined from Gaussian fitting of Δt histograms at a range of ATP concentrations (fig. S4). The inverse of tavg was plotted vs. ATP concentration and fitted well to the Michaelis-Menten equation, yielding Km of 180 μM (Fig. 2G). The length dependence and ATP dependence show that the ATPase activity of RIG-I powers its translocation on the entire length of dsRNA. The contrast between the slow movement of wtRIG and the 15-fold accelerated movement of RIGh is consistent with the significantly higher stimulation of ATPase activity by dsRNA observed in RIGh than in wtRIG (19) and with the report that CARDs inhibit the ATPase activity of RIG-I (8).

To further evaluate the regulatory role of CARDs, we tested the RIG-I splice variant, svRIG, which lacks amino acids 36–80 in the first CARD (25). svRIG confers dominant negativity in antiviral signaling, implying a loss of signaling function arising from a deficient CARD. The translocation activity of svRIG on dsRNA is highly similar to that of RIGh, characterized by much more rapid fluctuations compared to wtRIG (Fig. 2A and 2F). svRIG translocation is also ATP dependent with Km of 114 μM similar to that of RIGh (fig. S5). Thus, CARD-mediated suppression of translocation activity requires complete CARDs.

Apart from dsRNA, a powerful PAMP for RIG-I is 5′-triphosphate (2, 22). To examine if 5′-triphosphate influences the RNA translocation activity of RIG-I, we prepared 5′-triphosphate RNA (86mer) via in vitro transcription and annealed it to a complementary 20mer DNA strand. The DNA strand was modified with a 3′ fluorophore (Cy3) and 5′ biotin, which serves as a fluorescence reporter and a surface-tethering point, respectively (Fig. 3A). Addition of wtRIG and ATP to this substrate resulted in extremely rapid fluctuations in fluorescence signal (Fig. 3B, C). The rate of translocation, calculated as (tavg)−1, was dependent on the ATP concentration, with a Km value of 37 μM (fig. S6). RIGh showed translocation activity on 5′-triphosphate RNA with a comparable rate to wtRIG (Fig. 3D, E).

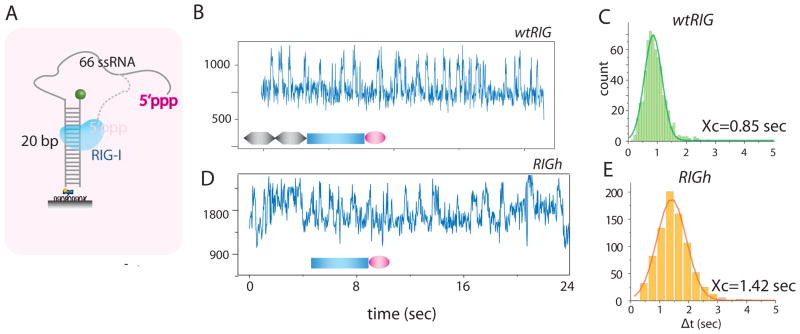

Fig. 3. 5′-triphosphate accelerates RIG-I translocation activity.

A. The translocation assay was performed on 5′-triphosphate containing substrate which consists of 86mer ssRNA from in vitro transcription annealed to complementary 20mer ssDNA with 3′ Cy3 and 5′ biotin.

B, D. Activity of wtRIG was greatly stimulated by the presence of 5′-triphosphate. The data shown was taken at room temperature due to extremely fast kinetic rate observed at 37°C. RIGh also showed robust translocation activity on this substrate. C, E. Dwell time analysis indicates that wtRIG showed slightly higher rate of translocation than RIGh.

wtRIG’s translocation on 5′-triphosphate RNA is over 20 times faster than on dsRNA (tavg of 18.5 s vs. and 0.85 s) (Fig. 1C, 3C). Combined with the data on RIGh and svRIG that showed rapid dsRNA translocation activity regardless of the presence of 5′-triphosphate, we conclude that (i) intact CARDs are necessary to negatively regulate the dsRNA translocation activity of RIG-I and that (ii) recognition of 5′-triphosphate by RD completely lifts the suppression by CARDs. Therefore, RNA translocation of RIG-I is regulated by its N-terminal (CARD) and C-terminal (RD) domains. Because the immobilized RNA molecules are more than 1 μm apart from each other, the effect of 5′-triphophate must be in cis, that is, RIG-I translocates rapidly on the same RNA that presents 5′-triphosphate. Adding up to 100 times molar excess of 5′-triphosphate containing ssRNA strand did not increase the translocation rate of wtRIG on dsRNA (fig. S7).

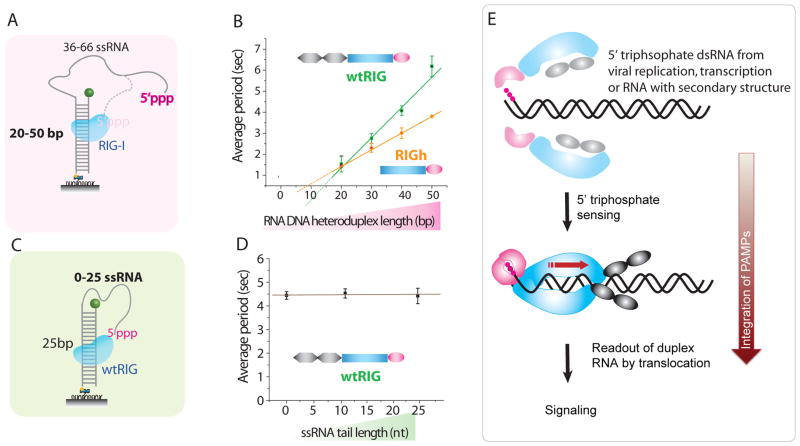

The 5′-triphosphate RNA we used has both single stranded and double stranded portions, where the double stranded portion is a RNA/DNA heteroduplex. Studies on various nucleic acid substrates showed that RIG-I is an RNA specific translocase that tracks one RNA strand either on dsRNA or RNA/DNA heteroduplexes (figs. S8 and S9). Does RIG-I, upon recognition of 5′-triphosphate, translocate on the ssRNA, the duplex region, or both? To answer this question, we progressively lengthened the duplex from 20 to 50 bp while progressively shortening the single stranded region proximal to 5′-triphosphate from 66 to 36 nt (Fig. 4A). tavg of both wtRIG and RIGh increased linearly with the duplex length, demonstrating translocation on duplex rather than ssRNA (Fig. 4B, fig S10). Varying the ssRNA tail length while keeping the same length dsRNA did not change tavg (Fig. 4C, 4D, fig. S11).

Fig. 4. RIG-I translocates on double strand of 5′-triphosphate RNA.

A. To identify the region of translocation, the double strand length was varied from 20bp to 50bp while ssRNA length was varied from 66nt to 36nt respectively. B. tavg vs duplex length. C. Three constructs were prepared with the fixed double strand RNA length of 25bp and variable ssRNA tail length of 0, 10 and 25nt. D. tavg vs ssRNA tail length. Error bars denote standard deviation from three separate experiments each. E. Proposed mechanism for pathogen associated molecular pattern (PAMP) signal integration by RIG-I. Binding of RIG-I regulatory domain (pink) to RNA 5′ triphosphates, e.g. arising from virus replication or transcription, dimerizes RIG-I and activates the translocase domain (blue). Further recognition of dsRNA stimulates ATPase activity resulting in translocation (red arrow), a process that may induce a signaling conformation with exposed CARDs (gray). Precise domain arrangements are speculative and depicted here for illustrative purposes.

The highly periodic, repetitive nature of the translocation signal, reminiscent of E. coli Rep and Hepatitis C virus NS3 helicases (26, 27), suggests that a single unit of RIG-I repeatedly moves on one RNA without dissociation. This was further verified by washing the reaction chamber with ATP containing buffer devoid of protein, which left a majority of molecules still in repetitive motion (fig. S13). As a further test, we labeled RIGh non-specifically with the acceptor fluorophore, and performed single molecule FRET experiments on the donor-labeled RNA. Periodic, anti-correlated changes of the donor and acceptor intensities were observed, consistent with RIG-I translocation on RNA (fig. S14).

The dsRNA translocation activity on RNA that contains 5′-triphosphate would serve as a signal verification mechanism by activating the ATPase only if the RNA features both PAMPs, the 5′-triphosphate and dsRNA. Thus, our data not only suggest a functional connection between the apparently different PAMPs but also indicate that integration of more than one PAMP in a single activation mechanism could be important for selective distinction of host from viral RNA.

What is the molecular function of the translocase activity? Translocation might effectively interfere with viral proteins by preventing them from binding, blocking their progression, or displacing them, thus actively interfering with viral replication (28). However, such a function does not explain why an ATPase deficient mutation of RIG-I lacks signaling activity. Perhaps repetitive shuttling at dsRNA regions of the viral genome, which may arise from genome replication, transcription or stable secondary structures, could provide a structural conformation in RIG-I with exposed CARDs to attract the next players in the signaling cascade (Fig. 4E). The signal strength is likely related to the amount of time spent in translocation mode and therefore to the length of RNA. This might explain how RIG-I and MDA5 may differentially read out very long dsRNA regions (13). Finally, our finding of RIG-I as a dsRNA translocase completes the range of activities in superfamily 2 DExH box ATPases, which now include single-strand and double-strand specific translocases for both RNA and DNA (29).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Joo and K. Ragunathan for careful review of the manuscript. Supported by NIH grant R01- GM065367 for T.H, NIH grants CA82057 for J.U.J, Human frontiers of science grant to T.H and K.P.H. K.P.H acknowledges support from the German excellence initiative. S.C is supported by DFG SFB 455 to K. P. H. A.K. acknowledges support from the DFG graduate school 1202. T.H is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S.M is a fellow at Institute for Genomic Biology.

References

- 1.Yoneyama M, et al. Nat Immunol. 2004 Jul;5:730. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornung V, et al. Science. 2006 Nov 10;314:994. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichlmair A, et al. Science. 2006 Nov 10;314:997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shatkin AJ, Manley JL. Nat Struct Biol. 2000 Oct;7:838. doi: 10.1038/79583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fromont-Racine M, Senger B, Saveanu C, Fasiolo F. Gene. 2003 Aug 14;313:17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00629-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh R, Reddy R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Nov;86:8280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumpter R, Jr, et al. J Virol. 2005 Mar;79:2689. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2689-2699.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jan 9;104:582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marques JT, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2006 May;24:559. doi: 10.1038/nbt1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gee P, et al. J Biol Chem. 2008 Apr 4;283:9488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuel CE. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001 Oct;14:778. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato H, et al. Nature. 2006 May 4;441:101. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H, et al. J Exp Med. 2008 Jul 7;205:1601. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gack MU, et al. Nature. 2007 Apr 19;446:916. doi: 10.1038/nature05732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meylan E, et al. Nature. 2005 Oct 20;437:1167. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. Cell. 2005 Sep 9;122:669. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu LG, et al. Mol Cell. 2005 Sep 16;19:727. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawai T, et al. Nat Immunol. 2005 Oct;6:981. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui S, et al. Mol Cell. 2008 Feb 1;29:169. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahasi K, et al. Mol Cell. 2008 Feb 29;29:428. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Immunity. 2008 Aug 15;29:178. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plumet S, et al. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo G, Wang M, Konigsberg WH, Xie XS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 31;104:12610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700920104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer CJ, Maluf NK, Lohman TM. J Mol Biol. 2004 Dec 10;344:1287. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gack MU, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Oct 28;105:16743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804947105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myong S, Rasnik I, Joo C, Lohman TM, Ha T. Nature. 2005 Oct 27;437:1321. doi: 10.1038/nature04049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myong S, Bruno MM, Pyle AM, Ha T. Science. 2007 Jul 27;317:513. doi: 10.1126/science.1144130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jankowsky E, Gross CH, Shuman S, Pyle AM. Science. 2001 Jan 5;291:121. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durr H, Korner C, Muller M, Hickmann V, Hopfner KP. Cell. 2005 May 6;121:363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.