Abstract

Objective:

We examined history of alcoholism and occurrence and timing of separation in parents of a female twin cohort.

Method:

Parental separation (never-together; never-married cohabitants who separated; married who separated) was predicted from maternal and paternal alcoholism in 326 African ancestry (AA) and 1,849 European/other ancestry (EA) families. Broad (single-informant, reported in abstract) and narrow (self-report or two-informant) measures of alcoholism were compared.

Results:

Parental separation was more common in families with parental alcoholism: By the time twins were 18 years of age, parents had separated in only 24% of EA families in which neither parent was alcoholic, contrasted with 58% of families in which only the father was (father-only), 61% of families in which only the mother was (mother-only), and 75% in which both parents were alcoholic (two-parent); corresponding AA percentages were 59%, 71%, 82%, and 86%, respectively. Maternal alcoholism was more common in EA never-together couples (mother-only: odds ratio [OR] = 5.95; two parent: OR = 3.69). In ever-together couples, alcoholism in either parent predicted elevated risk of separation, with half of EA relationships ending in separation within 12 years of twins’ birth for father-only families, 9 years for mother-only families, and 4 years for both parents alcoholic; corresponding median survival times for AA couples were 9, 4, and 2 years, respectively. EA maternal alcoholism was especially strongly associated with separation in the early postnatal years (mother-only: birth—5 years, hazard ratio [HR] = 4.43; 6 years on, HR = 2.52; two-parent: HRs = 5.76, 3.68, respectively).

Conclusions:

Parental separation is a childhood environmental exposure that is more common in children of alcoholics, with timing of separation highly dependent on alcoholic parent gender.

Studies have long documented higher rates of alcohol use and alcohol-related difficulties among separated or divorced individuals compared with the continuously married (e.g., Power et al., 1999; Wilsnack et al., 1984). Although increases in consumption and problem drinking are common following divorce (Bachman et al., 1997; Horwitz et al., 1996; Temple et al., 1991), there is also evidence of nonrandom selection both into and out of marriage as a function of prior alcohol involvement. Examined across the life span, individuals with a history of heavy or dependent drinking are less likely to marry (Fu and Goldman, 1996; Horwitz and White, 1991; Waldron et al., 2011), but once married, they are more likely to divorce (Caces et al., 1999; Collins et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 1998; Waldron et al., 2011).

Although presence of children is sometimes modeled in analyses of marital risks related to drinking, outcomes specific to parents are rarely, if ever, reported. As a consequence, whether parental alcohol involvement affects the probability that offspring experience parental separation or divorce is largely unknown. Research on the relationship between parental alcoholism and parental separation has particular relevance for understanding risks to children—compared with children whose parents are not alcoholic, children of alcoholics have higher rates of both externalizing and internalizing difficulties, including early and problem substance use (Sher et al., 1991; West and Prinz, 1987); higher rates have also been observed in children raised in single-parent homes (Amato and Keith, 1991; Emery, 1988; McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994).

In the present study, we examined parental separation as a function of maternal and paternal history of alcoholism, exploring the relative stability of parental unions. Given increasing numbers of children born outside of marriage (Wildsmith et al., 2011), we included in our analysis parents who never married but continuously cohabited or subsequently separated. As with divorce, higher rates of heavy and problem drinking are observed in never-married compared with married individuals (e.g., Hajema and Knibbe, 1998; Horwitz and White, 1991; Temple et al., 1991), including cohabiting unmarried couples (Caetano et al., 2006; Wilsnack et al., 1991), who themselves are at especially high risk for separation (Bramlett and Mosher, 2002).

In keeping with our focus on parental relationship dissolution from the temporal perspective of children, we examined timing of separation from offspring birth. In general, having very young children has been linked to increased marital stability, with reduced stability as children age beyond the preschool years (e.g., Waite and Lillard, 1991). Reduced stability is also observed for parents when children are born outside of marriage, including children of cohabiting parents who subsequently marry (e.g., Graefe and Lichter, 1999; Manning et al., 2004). Although a handful of studies are strongly suggestive of earlier divorce associated with respondent history of alcoholism (Kessler et al., 1998; Waldron et al., 2011), to date no published study has examined time to separation as a function of offspring age.

We also examined how timing of relationship dissolution varies by parent gender, comparing risk among families in which the mother or father is alcoholic or both parents are versus families in which neither parent has a history of alcoholism. Despite a number of studies including information on spouses (e.g., McLeod, 1993; Roberts and Leonard, 1998), a single study has examined whether drinking behavior of specific partners is differentially predictive of separation or divorce. Ostermann and colleagues (2005) found reduced rates of divorce in a representative sample of middle-aged couples who were initially concordant for drinking (e.g., two abstainers or two heavy drinkers) compared with couples in which only one spouse was a heavy drinker. However, history of problem drinking by either spouse was not uniquely predictive, and having minor-age children was modeled as a covariate only.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study (Heath et al., 1999, 2002), a prospective study targeting the total cohort of female like-sex twin pairs born in Missouri to Missouri-resident parents, identified from birth records, for the period July 1, 1975-June 30, 1985 (n = 370 African ancestry [AA]; n = 1,999 European, or in rare cases other, ancestry [EA] families). A cohort-sequential sampling design was used, with initial cohorts of 13-, 15-, 17-, and 19-year-old twins and their families recruited during the first 2 years of data collection, with continued recruitment of 13-year-olds in years 3 through 4. After a brief screening interview, parents were asked to complete a telephone diagnostic interview (Wave 1), with a subsample of mothers completing a 3-year retest interview. Three waves of telephone interview data collection targeted all available twin pairs (Waves 1, 4, and 5, at median ages 15, 22, and 24 years, respectively). Many but not all twin pairs from Wave 1 were scheduled to complete a brief 1-year follow-up (Wave 2), with a subsample also scheduled for a 3-year retest interview (Wave 3). For each wave, participants gave verbal consent (or assent if minors) following procedures approved by the institutional review board at Washington University.

Study participation (parent, twin Waves 1, 4, and 5) at the family level (e.g., number of families with at least one family member interviewed) is summarized in Figure 1. At Wave 4 (when twins were of minimum age 18) and Wave 5, the total population of twin pairs was retargeted for assessment, regardless of prior family participation and excluding only those twins who had either themselves requested no future contact or whose parents had refused all future contact. As shown, twins from 18% of target population families (n = 424) first entered the study at Wave 4. Only 4.1% of families (n = 96) never enrolled (including 5 not approached because of state law regarding adoption from birth, with 25 never located), and 2.8% (n = 66) dropped out of the study after completing the screener. For 91.4% of families, either Wave 1 or 4 data were obtained from at least one twin.

Figure 1.

Family-level study participation. Shown are numbers of families (European or other ancestry, African ancestry) and percentages relatives to total target population of like-sex twins, where at least one twin completed Waves 1, 4, or 5 interviews, subgrouped by presence or absence of parent interview data. Also shown are families where only a screening interview was completed and families never enrolled in the study, with the latter subgrouped by contact history.

Data from parent and twin Waves 1, 3, 4, and 5 were analyzed here. Across reporters and waves, 2,181 families (92%) had data on parental alcoholism and parental separation measures described below. Analyses were limited to 2,024 families (1,788 EA, 236 AA) in which parents were married or unmarried and living together at twins’ birth (ever together) and 151 families (61 EA, 90 AA) in which parents were unmarried and never lived together during twins’ lifetime (never together). Six families (5 EA, 1 AA) of twins who were adopted later in childhood or whose father was unknown or died before the twins’ birth were excluded. Numbers of families by available parent and offspring reporters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of available reporters from ever-together and never-together families (and total percentage), by race/ethnicity

| Variable | Both twins |

One twin |

Neither twin |

|||||||||

| Ever-together | Never-together | Total | (%) | Ever-together | Never-together | Total | (%) | Ever-together | Never-together | Total | (%) | |

| European or other ancestry families | ||||||||||||

| Parent | ||||||||||||

| Both | 988 | 4 | 992 | (54)a | 22 | 1 | 23 | (1)a | 7 | 1 | 8 | (<1)a |

| Mother only | 400 | 36 | 436 | (24)a | 31 | 2 | 33 | (2)a | 13 | 1 | 14 | (<1)a |

| Father only | 57 | 0 57 | (3)a | 4 | 0 | 4 | (<1)a | 11 | 0 | 11 | (<1)a | |

| Neither | 207 | 15 | 222 | (12)a | 48 | 1 | 49 | (3)a | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 1,652 | 55 | 1,707 | 105 | 4 | 109 | 31 | 2 | 33 | |||

| African ancestry families | ||||||||||||

| Parent | ||||||||||||

| Both | 64 | 13 | 77 | (24)b | 2 | 0 | 2 | (<1)b | 2 | 0 | 2 | (<1)b |

| Mother only | 79 | 44 | 123 | (38)b | 8 | 6 | 14 | (4)b | 0 | 2 | 2 | (<1)b |

| Father only | 9 | 3 | 12 | (4)b | 2 | 0 | 2 | (<1)b | 2 | 0 | 2 | (<1)b |

| Neither | 60 | 17 | 77 | (24)b | 8 | 5 | 13 | (4)b | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 212 | 77 | 289 | 20 | 11 | 31 | 4 | 2 | 6 | |||

Percentage of total European/other ancestry families;

percentage of total African ancestry families.

Measures

Measures derived largely from the Semi-Structured Assessment of the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA; Bucholz et al., 1994), a semi-structured interview developed for the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (Begleiter et al., 1995). The SSAGA has documented validity (Hesselbrock et al., 1999), with excellent retest and interrater reliability (Bucholz et al., 1994, 1995). Parents completed a telephone adaptation of the SSAGA-II—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), update to the DSM-III-R-based SSAGA. Twins completed either the child or adolescent version of the SSAGA-II, also adapted for telephone administration.

Parental separation.

History of separation during child-rearing years, through change in marital and/or cohabitation status for reasons of relationship dissolution, was coded from items included in nondiagnostic sections of the parent and Waves 1, 3, 4, and 5 twin interviews. Reported age at parental separation was highly correlated in twin pairs (r = .92, p < .0001); thus, twin reports were analyzed when parent report was either not available or uninformative (e.g., because parent report predated parental separation).

Parental alcoholism.

History of alcoholism was coded from parent self-report of alcohol dependence, parent ratings of co-parent dependence symptoms, and twin ratings of each parent as a problem and excessive drinker. Lifetime history of alcohol dependence was assessed by self-report in the parent interview and coded according to DSM-IV criteria. Alcohol dependence symptoms experienced by twins’ biological co-parent were assessed in the parent interview using the Family History Assessment Module (Rice et al., 1995), which was developed as a companion to the SSAGA for use in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Because temporal clustering of co-parent symptoms was not assessed, a probable dependence diagnosis without requiring 12-month clustering was coded. Twin ratings of each parent were drawn from Waves 1 and 4. Twin interviews did not ask detailed questions about parental dependence symptoms; instead, twins were asked whether “drinking ever caused your biological (mother/father) to have problems with health, family, job or police, or other problems,” an item that originated in the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria assessment (Andreasen et al., 1977), and whether they ever felt that their biological parent was an “excessive drinker.” Endorsement of both problem and excessive drinking was required to code a parent positive by twin report.

To minimize biases attributable to nonresponse, a parent was initially coded positive based on either self-report or any family history rating. Given reduced agreement among AA versus EA family members regarding the presence/absence of parental alcoholism (Waldron et al., 2012), a more conservative measure was also coded requiring, in the absence of a positive self-report, agreement between at least two family members (i.e., both twins, or co-parent and at least one twin). For this second measure, families without valid self-report and fewer than two family-history ratings were set to missing, thereby reducing samples of ever-together families from 2,024 to 1,930 families (1,708 EA, 222 AA) and never-together families from 151 to 123 (49 EA, 74 AA). In separate analyses, dummy variables were computed for both broad (single-informant) and narrow (self-report or two-informant) measures of parental alcoholism to distinguish families in which father only, mother only, or both were alcoholic from families in which neither parent had a history of alcoholism.

Maternal education.

Maternal education by self- or co-parent report, or twin report at Wave 5 (the only wave for which parental education was reported by twins), was included as a covariate in adjusted models (which therefore are based on slightly smaller ns than unadjusted models). Dummy variables for high school dropout and graduation (or earning the equivalent of a high school diploma) were computed from mother’s highest grade completed, with any tertiary education comprising the reference group. Paternal education was not examined because missingness for this variable was highly confounded with parental separation as were other potential covariates, including comorbid psychopathology (e.g., history of depression, conduct problems), which was available by parent self-report only.

Twin zygosity

Zygosity of twin pairs was diagnosed based on twins’ responses to standard questions regarding similarity and the degree to which others confused them (Nichols and Bilbro, 1966; Ooki et al., 1990). If Wave 1 or Wave 4 twin report was missing, parent responses to comparable questions were used.

Analytic strategy

All analyses were conducted separately for EA and AA families given racial/ethnic differences in both family structure (Bramlett and Mosher, 2002) and rates of alcohol problems (Grant, 1997; Hasin et al., 2007). Analyses were performed in STATA Version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), with the Huber-White robust variance estimator used to compute standard errors and confidence intervals adjusted for nonindependence (i.e., the correlated nature) of twin-family data.

Descriptive analyses were first conducted, including tests of differences by race/ethnicity and by twin pair zygosity, the latter to identify limitations to the generalizability of twin-family data. Nonresponse biases were examined by comparing participation rates of mothers, fathers, and twins as a function of parental separation and parental alcoholism. Never-together status was modeled by logistic regression. Survival analysis was used to model time-to-event data, with survival times reported as twins’ age in years, through age 18. Parents who separated before the twins’ first birthday were included in the risk set, with separation coded as a fraction of a year. Intact families were right-censored at twins’ age at last interview if younger than 18 years. In the case of parental death during childhood, intact families were right-censored at twins’ age when their parent(s) died. To summarize the changing proportion of twins living with only one biological parent as a function of parental alcoholism, Kaplan-Meier (Kaplan and Meier, 1958) failure curves were estimated for the entire sample (both ever- and never-together families). Kaplan-Meier cumulative failure probabilities were estimated for the entire sample and excluding never-together families. Cox proportional hazards regression (Cox, 1972) was conducted with results presented as hazard ratios (HRs), without versus with adjustment for maternal education, excluding never-together families. Post hoc tests comparing risk of separation associated with mother or father or both parents alcoholic were also conducted. To examine potential violation of the proportional hazards assumption in the case of differing effects of parental alcoholism on timing of separation for younger versus older twins, the Grambsch and Therneau test of Schoenfeld residuals (Grambsch and Therneau, 1994) was used. Where appropriate, age interactions were computed (Cleves et al., 2004), with risks specific to certain ages or periods chosen based on best correction of observed violations. In subsidiary analyses, timing of alcoholism relative to separation was examined in the subsample of ever-together alcoholic parents with valid self-report data (43 EA and 8 AA mothers, 53 EA and 7 AA fathers). As described, information regarding age at onset of alcoholism, including age at first symptom of dependence, is available from parent self-report only.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Descriptive statistics by race/ethnicity are summarized in Table 2 for ever- and never-together families. Among ever-together families, rates of parental separation were higher in AA versus EA families, as was parental death. Rates of mother-only alcoholism were higher in AA ever-together families if coded broadly (i.e., from single informants) but not when the narrow criterion was adopted requiring agreement among two family members in the absence of a positive self-report. Maternal education was also lower in ever-together AA versus EA families. Among never-together families, rates of mother-only alcoholism were lower in AA families regardless of broad versus narrow coding. No differences were observed by twin pair zygosity (not shown), with the exception of an increased risk of broadly defined paternal alcoholism in ever-together EA families with dizygotic pairs (p = .02).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, by race/ethnicity

| Variable | Ever-together families |

Never-together families |

||

| EA (n = 1,788) | AA (n = 236) | EA (n = 61) | AA (n = 90) | |

| Age at parent interview, M (SD) | ||||

| Mother | 42.01 (5.18) | 41.18 (5.22) | 36.38 (4.69)* | 38.66 (5.54)b,* |

| Father | 44.20 (5.79) | 44.21 (6.22) | 38.00 (5.51)* | 41.13 (7.26) |

| Twins | 15.37 (2.42) | 15.96 (2.60)b | 14.64 (2.13) | 15.55 (4.38) |

| Twins’ age at last interview, M (SD) | 23.82 (3.61) | 24.13 (3.51)b | 23.07 (3.16) | 23.36 (4.38) |

| Parental separation, n (%) | 647.(36) | 152.(64)b | – | – |

| Twins’ age at separation, M (SD) | 6.28 (4.90) | 5.67 (5.03)a | ||

| Parental death, n (%) | 86.(5) | 24.(10)b | 3.(5) | 9.(10) |

| Twins’ age at parental death, M (SD) | 10.52 (5.35) | 9.25 (5.86)a | 12.33 (8.08) | 8.00 (5.41) |

| Parental alcoholism, n (%) | ||||

| Broad (single-informant) | ||||

| Father-only | 448.(25) | 68.(29) | 12.(20) | 22.(24) |

| Mother-only | 78.(4) | 17.(7)b | 11.(18)* | 8.(9) |

| Both parents | 97.(5) | 17.(7) | 9.(15)* | 6.(7) |

| Narrow (self-report or two-informant) | ||||

| Father-only | 313.(18) | 41.(18) | 5.(10) | 13.(18) |

| Mother-only | 64.(4) | 9.(4) | 8.(16)* | 3.(4)a |

| Both parents | 39.(2) | 3.(1) | 1.(2) | 1.(1) |

| Maternal education, n (%) | ||||

| High school dropout | 166.(10) | 35.(16)b | 18.(30)* | 24.(27)* |

| College attendance | 868.(50) | 96.(44) | 19.(31)* | 33.(37) |

Notes: EA = European/other ancestry; AA = African ancestry.

EA > AA, p < .05;

AA > EA, p < .05.

Ever together versus never together differ within race/ethnicity, p < .05.

In EA families who were ever together, maternal and paternal alcoholism were modestly correlated for both measures (broad tetrachoric r = .36, asymptotic standard error [ASE] = 0.05; narrow r = .26, ASE = 0.06), with reduced associations in AA families (broad r = .22, ASE = 0.12; narrow r = .09, ASE = 0.19). Although nonsignificant, correlations between maternal and paternal alcoholism in never-together families were similar in magnitude with one exception—in EA families, there was little to no association using the narrow measure (r = -.04, ASE = 0.34).

Nonresponse biases

Parental separation predicted nonresponse of fathers in both ever-together EA and AA families (EA odds ratio [OR] = 0.49, 95% CI [0.41, 0.60]; AA OR = 0.56, 95% CI [0.32, 0.98]), with interviews completed by 50% of separated versus 67% of married/cohabiting EA fathers and 30% of separated versus 43% of married/cohabiting AA fathers. Completion of an interview by either twin was associated with parental separation in EA families only (OR = 0.46, 95% CI [0.23, 0.94]), with 97% versus 99% of twins from separated versus intact families having data. Results held when all families were analyzed (both ever together and never-together); in addition, parental separation predicted nonresponse of mothers in EA families (OR = 0.76, 95% CI [0.60, 0.96]), with interviews completed by 79% of separated versus 83% of married/cohabiting mothers.

Parental alcoholism predicted nonresponse in ever-together EA but not AA families. Using the broad measure, father-only, mother-only, and two-parent alcoholism were all associated with father nonresponse (father-only OR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.48, 0.75]; mother-only OR = 0.53, 95% CI [0.34, 0.84]; two-parent OR = 0.59, 95% CI [0.39, 0.89]), with 53%, 50%, and 53% of fathers participating, respectively, compared with 65% of fathers from nonalcoholic families. Father-only alcoholism was also associated with increased likelihood of mother’s participation (OR = 1.65, 95% CI [1.21, 2.25]), with 87% of mothers in families where father only was alcoholic participating versus 80% of mothers from nonalcoholic families. Comparable associations were found when never-together families were included, with two exceptions. In the combined sample, mother-only alcoholism was associated with decreased participation by mothers (OR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.37, 0.96]), with 71% of mothers participating versus 80% of mothers from nonalcoholic families. Mother-only alcoholism also predicted nonresponse by either twin in AA families (OR = 0.06, 95% CI [0.005, 0.71]), with 92% of twins having data compared with 99% from nonalcoholic families.

Never-together status

Using the broad measure, mother-only and two-parent alcoholism predicted never-together status in EA families only (mother-only OR = 5.95, 95% CI [3.54, 10.00]; two-parent OR = 3.69, 95% CI [2.10, 6.48]), with 13% and 8% of parents unmarried/not together during twins’ lifetime, respectively, compared with 2% of parents from nonalcoholic families. Effects were of similar magnitude when adjusted for maternal education. No significant associations with father-only alcoholism were observed in either EA or AA families.

Cumulative probabilities of parental separation

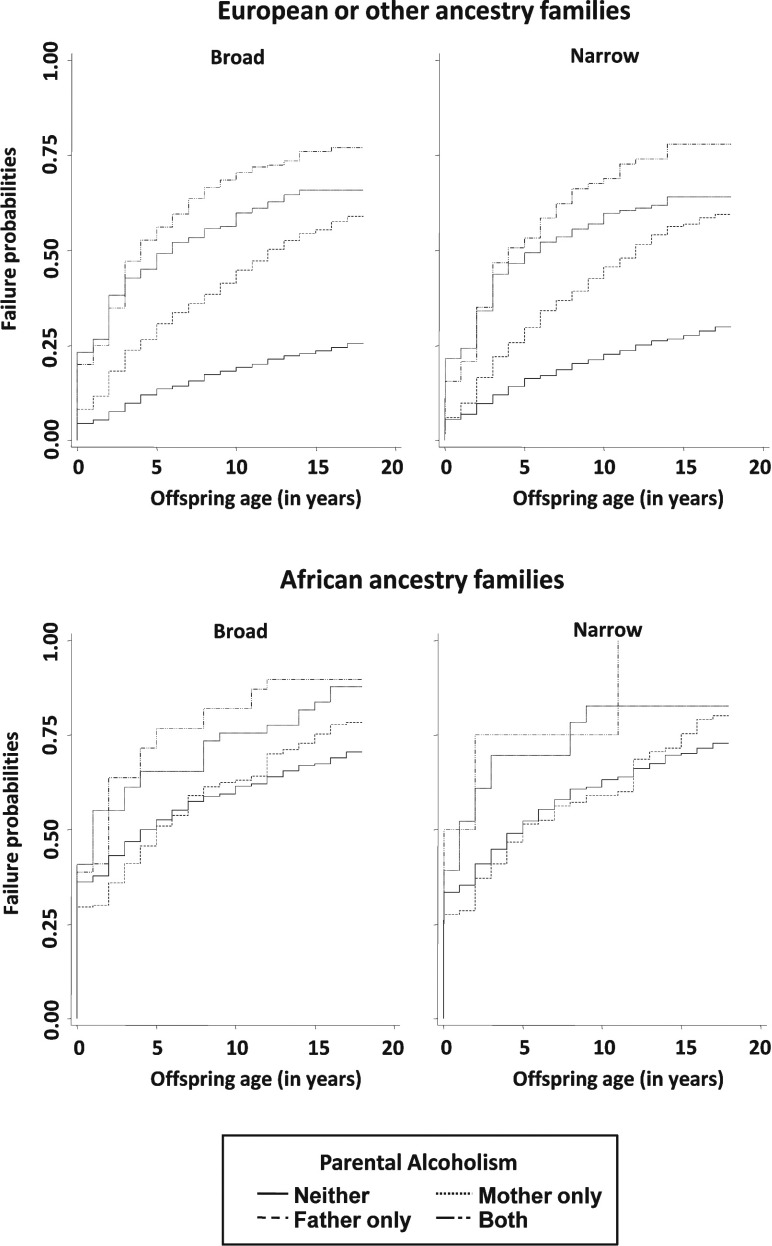

Cumulative failure curves by offspring age at separation and parental alcoholism are shown in Figure 2 for the entire sample. Using the broad measure of parental alcoholism, by the time EA twins were 18 years of age, 24% of ever-together families in which neither parent was alcoholic had separated. This compared with more than half in which father only (58%) or mother only (61%) had a history of alcoholism and three quarters (75%) in which both parents were alcoholic (respectively, 26%, 59%, 66%, and 77% when including never-together families). Median offspring ages at parental separation (i.e., survival times) for father or mother or both parents alcoholic were 12, 9, and 4, respectively. Results were comparable for the narrow measure: by twins’ age 18, 28% of ever-together families in which neither parent was alcoholic separated compared with 59% and 60%, respectively, when father or mother only had a history of alcoholism and 77% when both parents were alcoholic (30%, 60%, 64%, and 78% including never-together families). When father or mother only or both parents were alcoholic, 50% of offspring from ever-together families experienced separation by ages 12, 8, and 4 years, respectively.

Figure 2.

Kaplan—Meier failure curves of time to separation as a function of parental alcoholism and offspring age, by broad versus narrow measure, for European or other ancestry and African ancestry families.

Using the broad measure, 59% of ever-together AA families in which neither parent was alcoholic had separated, compared with 71% in which father only had a history of alcoholism, 82% in which mother only had a history of alcoholism, and 86% in which both parents were alcoholic (respectively, 70%, 78%, 88%, and 90% when including never-together families). Median offspring ages at parental separation for neither parent alcoholic, father or mother only, or both parents alcoholic were 12, 9, 4, and 2 years, respectively. Failure probabilities in AA families were roughly similar for the narrow measure; however, too few AA families were identified as having two alcoholic parents to allow confident characterization of survival time in this group. By the time AA twins were 18 years of age, 64% of families in which neither parent was alcoholic separated compared with 73% and 76% when father or mother only had a history of alcoholism (73%, 80%, and 83% including never-together families). When neither parent was alcoholic or father or mother only was alcoholic, 50% of offspring from ever-together families experienced separation by ages 10, 11, and 2, respectively.

Modeling time to parental separation

Hazard ratios from Cox regression models predicting onset of parental separation from parental alcoholism are shown in Tables 3 and 4 for EA and AA ever-together families, respectively, tabulated separately for broad versus narrow measures of alcoholism, unadjusted and adjusted for maternal education.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) from Cox proportional hazards models of parental separation for ever-together EA families, without versus with adjustment for maternal education

| Parental alcoholism |

||||

| Predictors (risk perioda) | Broad (single-informant) |

Narrow (self-report or two-informant) |

||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Father-only | ||||

| <8 | 2.72 [2.21, 3.34] | 2.66 [2.15, 3.29] | 2.34 [1.89, 2.88] | 2.26 [1.82, 2.80] |

| ≥8 | 3.85 [2.91, 5.08] | 3.84 [2.89, 5.11] | 3.20 [2.38, 4.29]b | 3.12 [2.31, 4.20]b |

| Mother-only | ||||

| <6 | 4.43 [3.11, 6.31] | 4.21 [2.93, 6.05] | 3.71 [2.56, 5.38] | 3.62 [2.50, 5.25] |

| ≥6 | 2.52 [1.41, 4.51]b | 2.55 [1.44, 4.53]b | 1.78 [0.90, 3.53] | 1.77 [0.89, 3.49]b |

| Both | ||||

| <8 | 5.76 [4.37, 7.59] | 5.34 [4.03, 7.08] | 4.68 [3.23, 6.79] | 4.54 [3.18, 6.49] |

| ≥8 | 3.68 [1.99, 6.81]b | 3.69 [2.00, 6.82]b | ||

| Education | ||||

| HS dropout | – | 1.75 [1.39, 2.20] | – | 1.92 [1.51, 2.43] |

| HS, no college, < 6 | – | 1.13 [0.92, 1.41] | – | 1.16 [0.93, 1.44] |

| HS, no college, ≥ 6 | – | 0.94 [0.73, 1.20]b | – | 0.94 [0.73, 1.21]b |

Notes: Where large brackets are shown, reported risk (hazard ratio to the left of the bracket) is equivalent across risk periods. EA = European/other ancestry; HS = high school.

Risk period in twins’ years of age;

post hoc test equating hazard ratios across risk periods did not show significant heterogeneity (p > .05), but proportional hazards assumption was violated and thus an age interaction was modeled with separate hazard ratios reported.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) from Cox proportional hazards models of parental separation for ever-together AA families, without versus with adjustment for maternal education

| Predictors (risk perioda) | Parental alcoholism |

|||

| Broad (single-informant) |

Narrow (self-report or two-informant) |

|||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Father-only | ||||

| <4 | 0.89 [0.55, 1.42] | 0.90 [0.56, 1.44] | 0.86 [0.49, 1.51] | 0.82 [0.48, 1.37] |

| 4–5 | 1.73 [1.10, 2.73] | 1.72 [1.07, 2.76] | 1.40 [0.86, 2.27]b | |

| ≥6 | 1.61 [0.92, 2.83]b | |||

| Mother-only | ||||

| <10 | 1.76 [1.03, 3.02] | 1.73 [0.96, 3.11] | 2.13 [0.99, 4.59] | 2.07 [0.93, 4.63] |

| ≥10 | –c | –c | ||

| Both | 2.31 [1.32, 4.03] | 2.17 [1.15, 4.08] | 3.01 [1.29, 6.99] | 3.05 [1.44, 6.43] |

| Education | ||||

| HS dropout | – | 1.19 [0.73, 1.94] | – | 1.40 [0.90, 2.20] |

| HS, no college | – | 1.04 [0.73, 1.47] | – | 1.02 [0.71, 1.47] |

Notes: Where large brackets are shown, reported risks (hazard ratios to the left of the bracket) are equivalent across risk periods. AA = African ancestry; HS = high school.

Risk period in twins’ years of age;

post hoc test equating hazard ratios across risk periods did not show significant heterogeneity (p > .05), but proportional hazards assumption was violated and thus an age interaction was modeled with separate hazard ratios reported;

cannot estimate.

In EA families (Table 3), having two alcoholic parents predicted between a three- and six-fold increase in likelihood of parental separation throughout childhood compared with nonalcoholic families. Mother-only alcoholism was significantly predictive of increased separation risk through age 5 (HRs range: 3.62–4.43). Although there was no longer a significant effect beyond age 5 in adjusted analyses using the narrow measure, broad confidence intervals indicate that this was primarily an effect of the relatively small number of separations occurring in association with maternal alcoholism in the period when offspring were ages 6–18 years. Father-only alcoholism showed an important effect through age 7 (HRs: 2.26–2.72) but then a substantially increased effect from ages 8 onward (HRs: 3.12–3.85). Maternal high school noncompletion was also an important predictor (HRs: 1.75–1.92), with little to no effect of maternal education beyond high school.

In AA families (Table 4), mother-only alcoholism, broadly defined, was associated with early separation across childhood (unadjusted HR = 1.76), with increased but nonsignificant effects through age 9 using the narrow measure (HRs: 2.07–2.13). A significant effect of father-only alcoholism was found for the period beyond 4 years, and only using the broad measure (HRs ∼ 1.7). Interestingly, the effects of two alcoholic parents on likelihood of separation were stronger for the narrow measure (HRs: 3.01–3.05) than for the broad (HRs: 2.17–2.31), both without age interaction. No unique effect of maternal education was observed for AA families.

Post hoc comparisons

In EA families, using the broad measure, significant differences in risk of separation were observed through offspring age 7 between father-only and mother-only alcoholism, χ2(1) = 5.43, p = .02, and between father-only and two-parent alcoholism, χ2(1) = 27.95, p < .0001. From age 8 onward, mother or father or both parents alcoholic were not differentially predictive of separation (i.e., effects could be equated). Results held for the narrow measure and when we adjusted for maternal education. In AA families, significant differences in risk of separation were observed between father-only and two-parent alcoholism in comparisons without age interaction, χ2(1) = 4.54, p = .03. The same pattern was found using the narrow measure but decreased to trend-level with adjustment for maternal education, χ2(1) = 2.92, p = .09.

Timing of parent self-report alcoholism and separation

Among ever-together parents who self-reported alcohol dependence, the majority of separated alcoholic parents in EA families and separated fathers in AA families had an onset of syndromal clustering that clearly predated separation by at least 1 year, with stronger evidence of temporal primacy of first symptom. In EA families, 39 of 43 (91%) alcoholic mothers reported that their first symptom predated separation, 35 (81%) of whom met full DSM-IV criteria before separation; 50 of 53 (94%) alcoholic fathers reported that their first symptom predated separation, 49 (92%) of whom met full criteria before separation. Although only 2 of 8 (25%) alcoholic AA mothers reported that their first symptom predated separation, with the same number meeting full criteria before separation, all 7 alcoholic AA fathers reported that their first symptom predated separation, 6 (86%) of whom met full criteria before separation.

Discussion

Associations between alcohol problems and relationship instability are widely reported in both research and clinical literatures on social correlates and consequences of alcoholism (Leonard and Eiden, 2007). However, little is known about the probability of parental separation or divorce, including timing of separation, for children of alcoholic parents. In the present study, we examined parental separation in both AA and EA twin families, modeling time to separation from offspring birth, as a function of parental history of alcoholism. In EA families, both maternal and paternal alcoholism predicted increased risk of parental separation throughout childhood. However, we found a distinctive pattern with respect to timing whereby risk for separation, relative to nonalcoholic families, was especially increased in the years immediately following birth through age 5 or 7 in families with a mother who was alcoholic (either mother only or both parents). In families with father-only alcoholism, the period of highest relative increase was somewhat delayed, from age 8 onward. In AA families, despite higher rates of parental separation and more modest sample sizes, we were nonetheless able to document maternal and paternal alcoholism effects on separation risk, particularly in families in which both parents were alcoholic, but with fewer significant age interactions. Thus, regardless of race/ethnicity, parental separation represents a common concomitant of parental alcoholism and thus an environmental context in which other familial influences (including genetic risks; Heath and Nelson, 2002) may be expressed.

Given diminished participation rates in families experiencing separation and in which mother or father or both parents were alcoholic, we combined self-report alcohol dependence with family history reports to minimize biases attributable to nonresponse. In Kaplan-Meier analyses, for both EA and AA families, comparable rates of separation, including median survival times, were observed using a broad measure of parental alcoholism (based on single-informant reports versus a more conservative measure that was conditioned on agreement of two other family members in the absence of a positive self-report). In Cox analyses, effects were also similar across broad and narrow measures, although somewhat reduced for the latter. A notable exception was for two-parent alcoholism in AA families, in which we observed a larger effect using the narrow measure. However, it is plausible that this difference relates to reduced agreement between AA informants as we previously reported (Waldron et al., 2012), in which the effect for narrowly defined alcoholism may be a consequence of improved quality of family history data in African American families.

We included maternal education in adjusted Cox analyses because reduced education has been linked to problem drinking (e.g., Crum et al., 1998) as well as to earlier marriage and subsequent risk of divorce (Amato, 2010; Bramlett and Mosher, 2002; Heaton, 2002; McLanahan, 2004). In EA families, risks related to parental alcoholism were modestly attenuated, with high school dropout uniquely predictive of separation, perhaps following from earlier marriage or cohabitation. In AA families, the effect of mother-only alcoholism was reduced in adjusted models, but no significant unique effect of high school dropout or graduation only was observed. Although the present study does not address mechanisms underlying observed associations between alcoholism and risk of separation, findings suggest that socioeconomic context, of which maternal education is a proxy (at least in EA families), is yet another in which risks associated with parental alcoholism may be experienced.

Among a host of likely processes contributing to marital or marriage-like relationship dissolution are proximal risks from heavy or problem drinking, particularly marital conflict (for a review, see Marshal, 2003). Consistent with increased risk associated with maternal alcoholism during earlier versus later childhood, recent studies suggest that disordered drinking may have greater consequences for marital adjustment when the wife is alcoholic, instead of or in addition to her husband (e.g., Cranford et al., 2011), perhaps because of potentially greater incompatibility of problem drinking with the traditional role of wife as primary homemaker responsible for caretaking of both children and her spouse. Personality may also play a role, albeit distally, along with comorbid psychopathology either upstream or consequent to alcoholism, as rates of antisociality and depressive symptoms are elevated among individuals with alcohol and substance use disorders (Grant et al., 2004; Regier et al., 1990), with higher rates also observed among individuals who are divorced (Kessler et al., 1998).

Because twins were first interviewed at median age 15, many years later than the median age at parental separation in families with parental alcoholism, our study was neither designed nor well positioned to answer questions of causality. Thus, although we cannot separate the direct effects of parental alcoholism from correlated difficulties (marital, psychiatric, etc.) in predicting time to separation, such processes may eventually be powerfully examined in the offspring generation, when twins have had more time to select partners and have children themselves. As there is at least one report of heritable covariation between alcohol dependence and timing of both marriage and separation (Waldron et al., 2011), follow-up of twin offspring will also be important for genetically informed analyses of prospectively characterized marital risks related to dependent drinking.

Additional limitations of the current research should be noted. As described, for many families, we lack father self-report data, and this is especially likely for separated families and those in which the father may have had more severe alcoholism. For some families, we also lack self-report data from mothers. Information about symptom onset is available only by parent self-report; thus, we have limited data on timing of alcoholism and remission relative to separation, and this is especially true of co-parent reports, which do not consider symptom clustering. Given that drinking often decreases among individuals who become married or have children (for a review, see Leonard and Rothbard, 1999), it is possible that an alcoholic parent is in remission before childbirth, let alone by time of separation. Thus, the effects that we describe are for lifetime history and likely will underestimate the effects of continuing chronic alcoholism. Although separation may also precede problem drinking for some (e.g., Bachman et al., 1997; Horwitz et al., 1996), results of analyses limited to available self-report data suggest that in EA families, the vast majority of alcoholic parents report onset of symptoms before separation. A similar pattern was observed of alcoholic fathers in AA families but in only a quarter of AA alcoholic mothers. Our sample of AA families is small, particularly AA families in which parents self-report alcohol dependence; thus, whether alcoholism predicts or is consequent to separation in AA families is especially unclear.

The majority of parental separations occurred before the start of the study. Thus, despite the high degree of inter-informant agreement we found for parental alcoholism, at least for EA families (Waldron et al., 2012), we cannot exclude recall biases that might inflate the association between paternal alcoholism and separation. In AA families, in which agreement is poorer, such biases may be more likely. We also limited our assessment to parent self-reports and co-parent reports of alcohol dependence. Alcohol abuse was not examined because agreement is weak between self- and co-parent report of abuse in the present sample (Waldron et al., 2012). Thus, potential associations between alcohol abuse and risk of separation remain unknown, and as a result correlated risk exposures from abusive but not dependent drinking are also unknown. Finally, our results were obtained using a cohort of female twin pairs and their parents. Although support for the generalizability of twin data was observed, analyses require replication in families with nontwin offspring and male offspring.

Conclusion

Despite limitations, we documented strong associations between alcoholism and marital or nonmarital separation of parents. Results emphasize the potential role of correlated environmental exposures—in this case parental separation— in understanding risks to children of alcoholics. Risks to children associated with parental separation or divorce have received surprisingly little empirical attention in the alcohol literature, and extension of these analyses to examine offspring outcomes will be important.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants AA09022, AA07728, AA11998, AA12640, AA15210, AA17242, and AA17688; National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA023696; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD52543; and National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH64134.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:650–666. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria: Reliability and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1977;34:1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg J, Johnston LD. Marriage, divorce, and parenthood during the transition to young adulthood: Impacts on drug use and abuse. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, editors. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 246–279. [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H, Reich T, Hesselbrock V, Porjesz B, Li T-K, Schuckit M, Rice J. The collaborative study on the genetics of alcoholism. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1995;19:228–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. Vital and Health Statistics, Series. 2002;23(22):1–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Hesselbrock VM, Shayka JJ, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Schuckit MA, Schmidt I, Reich T. Reliability of individual diagnostic criterion items for psychoactive substance dependence and the impact on diagnosis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:500–505. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caces MF, Harford TC, Williams GD, Hanna EZ. Alcohol consumption and divorce rates in the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:647–652. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Floyd LR, McGrath C. The epidemiology of drinking among women of child-bearing age. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1023–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleves M, Gould WW, Gutierrez RG. Introduction to survival data analysis with Stata, revised edition. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. The role of substance use in young adult divorce. Addiction. 2007;102:786–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Floyd FJ, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Husbands’ and wives’ alcohol use disorders and marital interactions as longitudinal predictors of marital adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:210–222. doi: 10.1037/a0021349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Ensminger ME, Ro MJ, McCord J. The association of educational achievement and school dropout with risk of alcoholism: A twenty-five-year prospective study of inner-city children. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:318–326. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. Marriage, divorce, and children’s adjustment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Goldman N. Incorporating health into models of marriage choice: Demographic and sociological perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1996;58:740–758. [Google Scholar]

- Graefe DR, Lichter DT. Life course transitions of American children: Parental cohabitation, marriage, and single motherhood. Demography. 1999;36:205–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol dependence in the United States: Results of the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:464–473. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajema KJ, Knibbe RA. Changes in social roles as predictors of changes in drinking behaviour. Addiction. 1998;93:1717–1727. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931117179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Howells W, Bucholz KK, Glowinski AL, Nelson EC, Madden PAF. Ascertainment of a mid-western US female adolescent twin cohort for alcohol studies: assessment of sample representativeness using birth record data. Twin Research. 2002;5:107–112. doi: 10.1375/1369052022974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK. Ascertainment of a twin sample by computerized record matching, with assessment of possible sampling biases. Behavior Genetics. 1999;29:209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Nelson EC. Effects of the interaction between genotype and environment. Research into the genetic epidemiology of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Research & Health. 2002;26:193–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB. Factors contributing to increasing marital stability in the United States. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:392–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock M, Easton C, Bucholz KK, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V. A validity study of the SSAGA—A comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, White HR. Becoming married, depression, and alcohol problems among young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:221–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, White HR, Howell-White S. Becoming married and mental health: A longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1996;58:895–907. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Walters EE, Forthofer MS. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders, III: Probability of marital stability. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1092–1096. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Rothbard JC. Alcohol and the marriage effect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;Supplement 13:139–146. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ, Majumdar D. The relative stability of cohabiting and marital unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review. 2004;23:135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41:607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur GD. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD. Spouse concordance for alcohol dependence and heavy drinking: Evidence from a community sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:1146–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols RC, Bilbro WC., Jr The diagnosis of twin zygosity. Acta Genetica et Statistica Medica. 1966;16:265–275. doi: 10.1159/000151973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooki S, Yamada K, Asaka A, Hayakawa K. Zygosity diagnosis of twins by questionnaire. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae. 1990;39:109–115. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000005626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann J, Sloan FA, Taylor DH. Heavy alcohol use and marital dissolution in the USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Rodgers B, Hope S. Heavy alcohol consumption and marital status: Disentangling the relationship in a national study of young adults. Addiction. 1999;94:1477–1487. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941014774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JP, Reich T, Bucholz KK, Neuman RJ, Fishman R, Rochberg N, Begleiter H. Comparison of direct interview and family history diagnoses of alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:1018–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LJ, Leonard KE. An empirical typology of drinking partnerships and their relationship to marital functioning and drinking consequences. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1998;60:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple MT, Fillmore KM, Hartka E, Johnstone B, Leino EV, Motoyoshf M. A meta-analysis of change in marital and employment status as predictors of alcohol consumption on a typical occasion. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1269–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Lillard LA. Children and marital disruption. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;96:930–953. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron M, Heath AC, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, Martin NG. Alcoholic marriage: Later start, sooner end. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:632–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron M, Madden PAF, Nelson EC, Knopik VS, Glowinski AL, Grant JD, Heath AC. The interpretability of family history reports of alcoholism in general community samples: findings in a midwestern U.S. twin birth cohort. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:590–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MO, Prinz RJ. Parental alcoholism and childhood psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102:204–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildsmith E, Steward-Streng NR, Manlove J. Childbearing outside of marriage: Estimates and trends in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Child Trends; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Klassen AD. Women’s drinking and drinking problems: Patterns from a 1981 national survey. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74:1231–1238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.11.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Klassen AD, Schur BE, Wilsnack RW. Predicting onset and chronicity of women’s problem drinking: A five-year longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:305–318. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]