Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about cancer survivors’ receptivity to being contacted through cancer registries for research and health promotion efforts. We sought to: (1) determine breast and colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors’ responsiveness to a mailed survey using an academic medical center’s cancer registry; (2) assess whether responsiveness varied according to sociodemographic characteristics and medical history; and (3) examine the prevalence and correlates of respondents’ awareness and willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry for future research studies.

Methods

Stage 0–III breast and CRC survivors diagnosed between January 2004 and December 2009 were identified from an academic medical center cancer registry. Survivors were mailed an invitation letter with an opt-out option, along with a survey assessing sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, and follow-up cancer care access and utilization.

Results

A total of 452 (31.4%) breast and 53 (22.2%) CRC survivors responded. Willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry was high among both breast (74%) and CRC (64%) respondents even though few were aware of the registry and even fewer knew that their information was in the registry. In multivariable analyses, tumor stage I and not having a family history of cancer were associated with willingness among breast and CRC survivors, respectively.

Conclusions

Our findings support the use of state cancer registries to contact survivors for participation in research studies.

Implications for cancer survivors

Survivors would benefit from partnerships between researchers and cancer registries that are focused on health promotion interventions.

Keywords: survivors, breast neoplasms, colorectal neoplasms, registries, recruitment

1. Introduction

The US cancer survivor population is projected to grow from over 13 million survivors [1] in 2012 to approximately 18 million by 2020 [2]. Delivery of comprehensive survivorship care is necessary to prevent and reduce late effects as well as ensure long-term survival [3]. For breast and colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors who comprise one-third of the total cancer survivor population [4] and for whom specific surveillance guidelines have been developed, post-treatment screening is critical for early detection of new and recurrent cancer, improved survival, and decreased mortality [5–8].

Despite the benefits of post-treatment screening, studies consistently show that breast and CRC survivors do not adhere to recommended guidelines. Regardless of differences in study design (definitions of adherence, measurement, and tests), rates of mammography and colonoscopy among survivors are no better than screening rates in average-risk populations. Post-treatment screening rates for mammography range from 53–92% [9–18] and for CRC screening with colonoscopy, they range from 18–80% [19–26]. More importantly, rates decline over time, or tests are not done consecutively at recommended intervals for either mammography [10, 11, 27] or colonoscopy [6, 20, 25]. Adherence rates to follow-up office visits or other recommended tests for breast [28] or CRC [13, 23, 25] survivors are even lower.

Most post-treatment screening studies of breast and CRC survivors have been conducted within clinic settings in which survivors have access to healthcare; thus, little is known about whether adherence is a problem at the population-level. Cancer registries may represent a viable tool for measurement of post-treatment screening and early detection behaviors among the growing population of survivors. Registries may also provide opportunities to promote comprehensive survivorship care at a population-level by notifying survivors about the importance of following recommended guidelines. Historically, registries have collected data for cancer outcomes research with little direct patient contact [29]. Few have used registries for health promotion interventions with survivors, perhaps due to concerns regarding the best way to approach survivors given patient confidentiality laws and the potential for privacy violation [30].

Little is currently known about survivors’ receptivity to being contacted through cancer registries for research and health promotion efforts. Accordingly, our study objectives were threefold: (1) determine breast and CRC survivors’ responsiveness to a mailed survey using an academic medical center’s cancer registry; (2) assess whether responsiveness varied according to sociodemographic characteristics and medical history; and (3) examine the prevalence and correlates of respondents’ awareness and willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry for future research studies. As this represents an exploratory study, no a priori hypotheses were made regarding correlates of willingness.

2. Methods

All stage 0–III breast and CRC survivors diagnosed between January 2004 and December 2009 (n=1,750; 1,510 breast, 240 CRC) and listed in an academic medical center cancer registry were identified. Duplicate survivors were removed in addition to a single male breast cancer case, resulting in a final recruitment sample of 1,680 survivors (1,441 breast, 239 CRC). All survivors were randomized based on gift card incentive ($10, $20, or entry into a lottery for a $100 gift card). In July 2011, survivors were mailed an invitation letter that indicated the type and amount of the incentive along with a survey that assessed sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, and access and utilization of follow-up cancer care. Letters utilized a passive consent procedure and included an option to opt-out. Responses were collected through March 2012. This study was approved by the institutional reviews boards of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and UT Southwestern Medical Center/Simmons Cancer Center.

2.1. Measures

Outcome variables

We assessed breast and CRC survivors’ response rates to the mailed survey. Awareness of the state cancer registry was assessed with two questions: whether they were aware of the state cancer registry and whether they were aware that their cancer information was listed in the state cancer registry. Survivors were also asked whether they would be willing to be contacted through the state cancer registry for future research studies.

Correlates

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, incentive level, marital status, and education were obtained by self-report except in the following cases. If survivors’ birth dates were missing or unclear, then birth date in the registry, was used to calculate age. If race/ethnicity differed between registry and self-report data, we used survivors’ self-report.

Medical history variables examined included cancer type, tumor stage, years since diagnosis, family history of cancer, and whether the respondent saw a genetic counselor. The first three variables were obtained via registry data while the family history and genetic counselor variables were based on self-report. Tumor stage was classified according to American Joint Committee on Cancer, 6th edition [31].

Access and utilization of follow-up cancer care were assessed with four self-report variables: insurance status, whether follow-up care was received in 2010–2011, type of provider seen for follow-up care, and overall health status. Response categories for all variables are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics, medical history, and access and utilization of follow-up cancer care of breast and CRC survivors listed in an academic medical center cancer registry and survey respondents.

| Breast Registry Sample (n=1,441) | CRC Registry Sample (n=239) | Comparison Breast & CRC Respondents |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents | Non-respondents | p-valuea | Respondents | Non-respondents | p-valueb | p-valuec | |||||

| Variables | ne | % | ne | % | ne | % | ne | % | |||

| Overall | 452 | 31.4 | 989 | 68.6 | 53 | 22.2 | 186 | 77.8 | |||

| Sociodemographics | |||||||||||

| Age (y) | 0.004 | 0.896 | 0.252 | ||||||||

| ≤49 | 63 | 13.9 | 210 | 21.2 | 5 | 9.4 | 16 | 8.6 | |||

| 50–64 | 228 | 50.4 | 443 | 44.8 | 22 | 41.5 | 72 | 38.7 | |||

| 65+ | 161 | 35.6 | 336 | 34.0 | 26 | 49.1 | 98 | 52.7 | |||

| Female sex | 31 | 58.5 | 92 | 49.5 | 0.246 | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.924 | ||||||||

| NH White | 336 | 74.3 | 555 | 56.1 | 40 | 75.5 | 82 | 44.1 | |||

| NH Black | 65 | 14.4 | 223 | 22.5 | 8 | 15.1 | 45 | 24.2 | |||

| Hispanic | 37 | 8.2 | 150 | 15.2 | 3 | 5.7 | 39 | 21.0 | |||

| Other/unknown | 14 | 3.1 | 61 | 6.2 | 2 | 3.8 | 20 | 10.8 | |||

| Incentive | 0.002 | 0.145 | 0.140 | ||||||||

| $10 | 145 | 32.1 | 329 | 33.3 | 12 | 22.6 | 68 | 36.6 | |||

| $20 | 176 | 38.9 | 298 | 30.1 | 19 | 35.8 | 60 | 32.3 | |||

| $100 lottery | 131 | 29.0 | 362 | 36.6 | 22 | 41.5 | 58 | 31.2 | |||

| Marital statusd | 0.006 | ||||||||||

| Married/living with partner | 300 | 67.1 | 25 | 48.1 | |||||||

| Other | 147 | 32.9 | 27 | 51.9 | |||||||

| Educationd | 0.121 | ||||||||||

| <HS/HS diploma/GED | 78 | 17.4 | 14 | 29.8 | |||||||

| Some college/tech degree | 140 | 31.3 | 16 | 34.0 | |||||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 138 | 30.8 | 9 | 19.2 | |||||||

| Graduate degree | 92 | 20.5 | 8 | 17.0 | |||||||

| Medical history | |||||||||||

| Tumor stagee | 0.016 | 0.298 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| 0 | 81 | 22.2 | 147 | 18.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 3.4 | |||

| I | 137 | 37.5 | 271 | 33.7 | 11 | 20.8 | 46 | 26.3 | |||

| II | 114 | 31.2 | 265 | 32.9 | 26 | 49.1 | 66 | 37.7 | |||

| III | 33 | 9.0 | 122 | 15.2 | 16 | 30.2 | 57 | 32.6 | |||

| Years since dx | 0.000 | 0.632 | 0.300 | ||||||||

| <5 y | 313 | 69.2 | 580 | 58.6 | 33 | 62.3 | 109 | 58.6 | |||

| 5+ y | 139 | 30.8 | 409 | 41.4 | 20 | 37.7 | 77 | 41.4 | |||

| Family cancer historyd | 132 | 29.2 | 14 | 28.0 | 0.859 | ||||||

| Saw genetic counselord | 139 | 31.7 | 7 | 14.9 | 0.017 | ||||||

| Access & utilization | |||||||||||

| Insurance statusd | 0.010 | ||||||||||

| Private/VA | 298 | 67.0 | 21 | 44.7 | |||||||

| Medicare/Medigap/Medicaid | 108 | 24.3 | 19 | 40.4 | |||||||

| County/none | 39 | 8.8 | 7 | 14.9 | |||||||

| Received care in 2010–2011d | 403 | 89.2 | 39 | 73.6 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Provider seend | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| No one | 48 | 10.6 | 14 | 26.4 | |||||||

| PCP | 12 | 2.7 | 8 | 15.1 | |||||||

| Oncologist | 313 | 69.3 | 25 | 47.2 | |||||||

| Both PCP & oncologist | 79 | 17.5 | 6 | 11.3 | |||||||

| Overall healthd | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| Excellent | 61 | 13.7 | 5 | 9.8 | |||||||

| Very good | 167 | 37.6 | 8 | 15.7 | |||||||

| Good | 159 | 35.8 | 19 | 37.3 | |||||||

| Fair/poor | 57 | 12.8 | 19 | 37.3 | |||||||

CRC, colorectal; y, years; NH, non-Hispanic; HS, high school; GED, general equivalency diploma; tech, technical; VA, Veterans Affairs; PCP, primary care provider

P-value reflects comparisons between breast respondents and non-respondents and variables of interest.

P-value reflects comparisons between CRC respondents and non-respondents and variables of interest.

P-value reflects comparisons between breast and CRC respondents and variables of interest.

These variables were ascertained by the survey; thus, data are only available for survey respondents.

Missing values ranged from 0 for most variables to 184 for tumor stage of breast non-respondents. Tumor stage was only collected consistently beginning in 2006.

2.2. Data Analysis

We compared survey response rates for all breast and CRC survivors in the recruitment sample (n=1,680). In stratified analyses by cancer type, we examined whether responsiveness varied by sociodemographic and medical history correlates available in the registry (n=1,441 for breast, n=239 for CRC). We tested whether breast and CRC survey respondents differed on awareness of and willingness to be contacted for future research through the state cancer registry (n=442 for breast, n=52 for CRC). To examine correlates of willingness to be contacted, we stratified analyses by cancer type and used all of the correlates listed above. We used chi-square tests for all comparisons; statistical significance was based on p < .05.

To identify correlates of willingness that remained significantly associated in multivariable analyses, we ran logistic regressions in which all variables with a p < .25 [32] were included unless highly correlated with another covariate of interest (e.g., family history and genetic counselor visits).

3. Results

3.1. Survivors’ Responsiveness to Contact from Academic Medical Center Cancer Registry

Breast cancer survivors had significantly higher survey response rates than CRC survivors (31.4% and 22.2%, respectively, Table 1). Approximately 22.2% of breast cancer survey respondents were in situ (stage 0) patients whereas all CRC survey respondents were diagnosed at stage I and higher. Within cancer type (breast and CRC), there were significant differences in the characteristics of those who responded to the survey. Breast cancer survivors who were 50–64 years of age, non-Hispanic White, randomized to a $20 incentive, diagnosed with a stage I tumor, and less than 5 years since diagnosis were more likely to respond to the survey (Table 1). Among CRC survivors, responsiveness only varied significantly by race/ethnicity, with CRC respondents largely of non-Hispanic White race/ethnicity.

3.2. Comparison of Breast and CRC Respondent Characteristics

Breast cancer respondents were more likely to be married/living with a partner in contrast to CRC respondents (67.1% vs. 48.1%; Table 1). Breast cancer respondents were more likely to report being diagnosed with a stage I tumor whereas CRC respondents were more likely to report a stage II diagnosis. Breast cancer respondents were also more likely to report: genetic counselor visits, private/VA insurance, receipt of follow-up care in 2010–2011, and an oncologist as the source for their follow-up care than were CRC respondents. Finally, breast cancer respondents were more likely to rate their overall health as “very good” whereas CRC respondents were more likely to rate their health as “good” to “fair/poor”.

3.3. Respondents’ Willingness to be Contacted through the State Cancer Registry

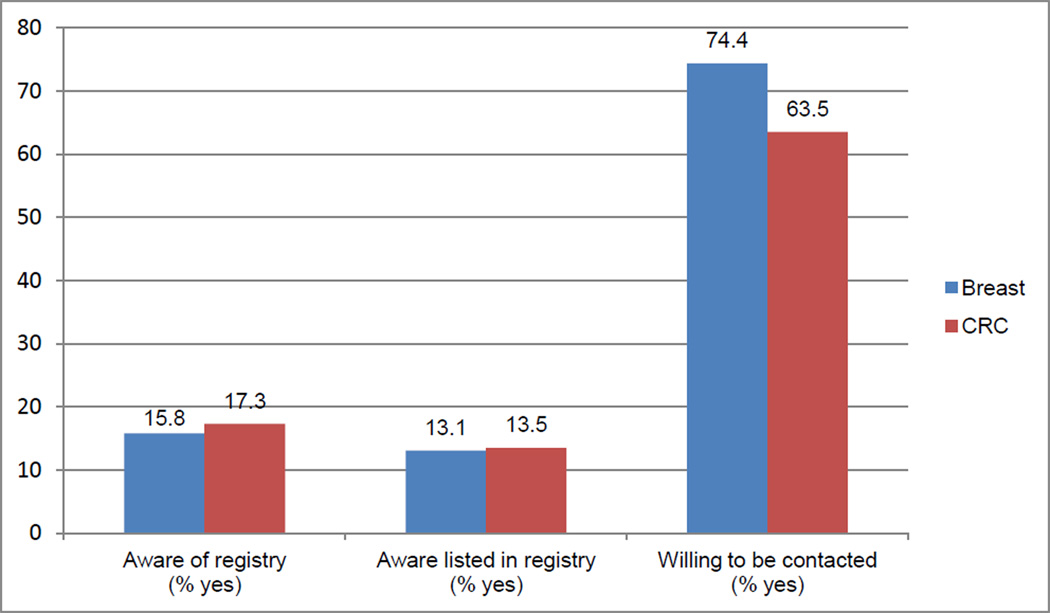

Among breast cancer survey respondents, willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry for future research studies was high (74.4%) even though few were aware of the registry (15.8%) and even fewer knew that their information was in the registry (13.1%; Figure 1). Similarly, 63.5% of CRC respondents indicated willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry, while only 17.3% reported awareness of the registry and 13.5% reported knowledge of being listed in the registry.

Fig. 1.

Awareness of and willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry for future research among breast and CRC survey respondents contacted through an academic medical center cancer registry in 2011, p > .05

Factors significantly associated at p < 0.25 with willingness in univariable analyses differed for breast and CRC respondents (Table 2). Among breast cancer respondents, willingness was associated with younger age, being married or living with a partner, more formal education, being diagnosed with a lower stage tumor, and seeing a genetic counselor. Among CRC respondents, those reporting a family history of cancer were less willing to be contacted as were those who saw a genetic counselor, whereas receiving follow-up care in 2010–2011 was positively associated.

Table 2.

Distribution of characteristics and multivariate logistic regression models of breast and CRC survey respondents’ willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry for future research.

| Willingness to be contacteda % |

Multivariate Modelsb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast (n=442) |

CRC (n=52) |

Breast (n=353)c |

CRC (n=49)c |

|||||

| Variables | nd | % | p-valuee | nd | % | p-valuef | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Overall willingness | 329 | 74.4 | 33 | 63.5 | 0.091g | |||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||

| Age (y) | 0.003 | 0.923 | ||||||

| ≤49 | 54 | 90.0 | 3 | 60.0 | 2.96 (0.99–8.85) | |||

| 50–64 | 170 | 74.9 | 14 | 66.7 | 0.94 (0.54–1.63) | |||

| 65+ | 105 | 67.7 | 16 | 61.5 | Reference | |||

| Sex | 0.848 | |||||||

| Female | 20 | 64.5 | ||||||

| Male | 13 | 61.9 | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.959 | 0.630 | ||||||

| NH White | 244 | 74.2 | 27 | 67.5 | ||||

| NH Black | 47 | 73.4 | 3 | 42.9 | ||||

| Hispanic | 27 | 77.1 | 2 | 66.7 | ||||

| Other/unknown | 11 | 78.6 | 1 | 50.0 | ||||

| Incentive | 0.619 | 0.823 | ||||||

| $10 | 108 | 75.0 | 7 | 58.3 | ||||

| $20 | 121 | 72.0 | 11 | 61.1 | ||||

| $100 lottery | 100 | 76.9 | 15 | 68.2 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.080 | 0.585 | ||||||

| Married/living with partner | 229 | 77.1 | 16 | 66.7 | 1.59 (0.93–2.72) | |||

| Other | 97 | 69.3 | 16 | 59.3 | Reference | |||

| Education | 0.008 | 0.548 | ||||||

| <HS/HS diploma/GED | 48 | 65.8 | 7 | 53.9 | Reference | |||

| Some college/technical degree | 94 | 68.1 | 9 | 56.3 | 0.82 (0.41–1.67) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 108 | 79.4 | 7 | 77.8 | 1.04 (0.49–2.21) | |||

| Graduate degree | 77 | 83.7 | 6 | 75.0 | 2.30 (0.91–5.80) | |||

| Medical history | ||||||||

| Tumor stage | 0.166 | 0.468 | ||||||

| 0 | 54 | 66.7 | 0 | 0.0 | Reference | |||

| I | 106 | 79.7 | 7 | 63.6 | 2.07 (1.07–4.01) | |||

| II | 85 | 75.2 | 14 | 56.0 | 1.35 (0.70–2.63) | |||

| III | 22 | 68.8 | 12 | 75.0 | 1.17 (0.47–2.94) | |||

| Years since diagnosis | 0.556 | 0.316 | ||||||

| <5 y | 231 | 75.2 | 22 | 68.8 | ||||

| 5+ y | 98 | 72.6 | 11 | 55.0 | ||||

| Family cancer history | 0.723 | 0.005 | ||||||

| No | 233 | 74.0 | 27 | 75.0 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 96 | 75.6 | 4 | 30.8 | 0.19 (0.04–0.83) | |||

| Saw genetic counselor | 0.008 | 0.211 | ||||||

| No | 209 | 71.3 | 27 | 67.5 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 114 | 83.2 | 3 | 42.9 | 1.27 (0.68–2.37) | |||

| Access & utilization | ||||||||

| Insurance status | 0.878 | 0.882 | ||||||

| Private/VA | 219 | 75.0 | 14 | 66.7 | ||||

| Medicare/Medigap/Medicaid | 77 | 72.6 | 11 | 61.1 | ||||

| County/none | 27 | 73.0 | 4 | 57.1 | ||||

| Follow-up care in 2010–2011 | 0.656 | 0.221 | ||||||

| No | 37 | 77.1 | 7 | 50.0 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 292 | 74.1 | 26 | 68.4 | 1.25 (0.75–2.08) | |||

| Type of provider seen | 0.918 | 0.640 | ||||||

| No one | 36 | 76.6 | 7 | 50.0 | ||||

| PCP | 8 | 66.7 | 6 | 75.0 | ||||

| Oncologist | 228 | 74.5 | 16 | 66.7 | ||||

| Both PCP and oncologist | 57 | 74.0 | 4 | 66.7 | ||||

| Overall health | 0.986 | 0.722 | ||||||

| Excellent | 44 | 73.3 | 3 | 75.0 | ||||

| Very good | 124 | 75.6 | 5 | 62.5 | ||||

| Good | 116 | 74.4 | 13 | 68.4 | ||||

| Fair/poor | 41 | 74.6 | 10 | 52.6 | ||||

CRC, colorectal; y, years; NH, non-Hispanic; HS, high school; GED, general equivalency diploma; VA, Veterans Affairs; PCP, primary care provider

Non-respondents to the willingness question (n = 10 for breast, n = 1 for CRC) were excluded from analyses.

Variables associated with willingness in univariable analyses (p<.25) were entered into multivariable models unless highly correlated with other variables. Shaded cells reflect those variables not entered into multivariable models.

Breast and CRC sample size was further reduced by 89 and 3, respectively, due to missing values on variables of interest.

Missing values ranged from 0 for most variables to 62 for tumor stage.

Reflects univariable comparisons between breast respondents’ willingness (no, yes) to be contacted and variables of interest.

Reflects univariable comparisons between CRC respondents’ willingness (no, yes) to be contacted and variables of interest.

Reflects univariable comparison between willingness (no, yes) to be contacted and cancer type (breast, CRC).

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In the multivariable model for breast cancer respondents, only lower tumor stage remained associated with willingness (Table 2). In the multivariable model for CRC, only family history of cancer remained associated with willingness.

4. Discussion

Our response rate of 31.4% for breast cancer survivors was in the range reported by other studies using state and hospital-based cancer registries where response rates ranged from 9–83% [33–39]. In our CRC sample, 22.2% responded; other CRC studies reported response rates ranging from 23–47% [39–41]. Our response rate is likely at the low end of the range because we mailed the survey only once while other studies employed varying combinations of time- and resource-intensive methods such as physician notification and/or permission prior to participant mailings; participant opt-in feature; follow-up mailings and phone calls; and re-querying of registry databases for updated participant contact information [33–38, 40, 41].

Consistent with some previous research [34, 36], we found that younger (compared to older) and non-metastatic (compared to metastatic) breast cancer survivors and non-Hispanic White (compared to non-White) breast and CRC survivors were more likely to respond. We also observed that randomization to a $20 gift card incentive (compared to $10 and $100 lottery) significantly increased breast cancer survivors’ responsiveness to our mailed survey. Because only a few cancer registry studies to date have examined correlates of responsiveness [34–36, 40], additional research is warranted in order to identify specific subgroups of survivors who may require more targeted recruitment efforts. Moreover, given that our documented impact of incentives on responsiveness differs from the non-significant findings observed in similar albeit few studies, [39] further research is needed that explores the optimal denomination of incentive required to encourage survivors’ responsiveness to recruitment through cancer registries.

Breast cancer survivors reported better follow-up cancer care access and utilization compared to CRC survivors. One potential explanation is the well-established breast cancer advocacy movement which has drawn intense public, scientific, and legislative attention to the need for breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment as well as funding for these types of care [42–44]. In contrast, CRC has been notably under-represented in advocacy efforts despite being the second most common cancer in both women and men [45]. It may be that breast cancer survivors are more connected to the health care system prior to diagnosis (e.g., through annual screening mammograms), a pattern that persists into survivorship. Alternatively, greater follow-up care utilization may reflect breast cancer survivors’ increased frequency of recommended follow-up care compared to that of CRC survivors. More frequent contact with the system may translate into increased cancer care. Gender differences may also explain the observed differences by cancer site, although we were unable to explore this given small cell sizes and low statistical power.

The fact that most breast and CRC respondents were willing to be contacted through the state cancer registry despite being unaware of it and unaware that their information was in the registry was noteworthy. Because awareness is low, survivorship research studies that recruit through registries should provide an introduction to the mission and purpose of state cancer registries. Research is needed to identify effective methods of educating and reassuring cancer patients about registries, including their purpose, type of data collected, potential for being contacted, and the safeguards in place to protect their privacy [30]. Researchers should also determine the best time to inform patients about the registry (e.g., at the time of or shortly following diagnosis or as a precursor to research recruitment [34, 46]). Our finding that, in contrast to breast cancer survivors, CRC survivors with a family cancer history were less willing to be contacted through the registry than those without a family history is not readily explained. It is possible that CRC survivors with a family history are concerned about intrusions into the privacy of family members who may not want this information disclosed. This explanation is consistent with our finding that willingness was lower among CRC survivors who had seen a genetic counselor. Additional research is needed to understand this differential pattern of association between breast and CRC survivors’ family cancer history and willingness.

Our study had some limitations. There was a small available pool of CRC survivors from which to recruit resulting in a small sample of CRC respondents. Because our sample was drawn from an academic medical center cancer registry of largely non-Hispanic White patients with access to health care, our findings may have limited generalizability. Self-selection is another possible limitation; non-respondents to the survey differed from respondents on several characteristics for both breast and CRC survivors. We also did not compare self-report of follow-up cancer care access and utilization to data in the electronic medical record. Despite the fact that willingness to be contacted through the state cancer registry was high among survey respondents, it remains unknown whether these individuals would follow through with participation. Future studies should assess concordance between survivors’ willingness to be contacted and their actual study participation. Finally, among the stage 0 (in situ) breast cancer patients recruited for this study, a handful opted out because they reported not being diagnosed with cancer; others chose to respond but specified on the survey that they only had precancerous cells. These responses suggest that this subgroup may not self-identify as a cancer survivor. Researchers should be careful when describing and extending study invitations to in situ patients. Additional research is needed on how to best communicate their greater risk for breast cancer compared to the general population and the importance of continued surveillance.

Conclusion

Cancer registries have historically focused solely on collecting patient data; however, the opportunity exists for registries to help conduct health promotion interventions with survivors. Our finding that approximately two-thirds of survivors were willing to be contacted through the state cancer registry for research participation illustrates this unmet opportunity. Working with state registries for recruitment is cost effective both in terms of time and staff effort [36, 47] and may provide researchers with a method to disseminate efficacious health behavior interventions to survivors when funding has ended [36]. Moreover, recruitment of racially and ethnically diverse population-based samples is necessary to generalize findings to the larger survivor population [36, 47], an aspect which has been lacking in survivorship research given its predominant focus on clinic or hospital-based samples.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements of funding: This study was funded by the Moncrief Cancer Institute. Funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute supported MYC (K07CA140159) and SWV (R01CA112223). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Moncrief Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Reference List

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2012–2013. [Accessed 18 June 2012]. Last update 2012. a-42. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-033876.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield SSE. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, Cooper D, Gansler T, Lerro C, Fedewa S, Lin C, Leach C, Cannady RS, Cho H, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Kirch R, Jemal A, Ward E. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lash TL, Fox MP, Buist DS, Wei F, Field TS, Frost FJ, Geiger AM, Quinn VP, Yood MU, Silliman RA. Mammography surveillance and mortality in older breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3001–3006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper GS, Kou TD, Reynolds HL., Jr Receipt of guideline-recommended follow-up in older colorectal cancer survivors: a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2008;113:2029–2037. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Follow-up after curative resection of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1783–1799. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffery GM, Hickey BE, Hider P. Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002200.pub2. CD002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslau ES, Jeffery DD, Davis WW, Moser RP, McNeel TS, Hawley S. Cancer screening practices among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer survivors: results from the 2001 and 2003 California health interview survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carcaise-Edinboro P, Bradley CJ, Dahman B. Surveillance mammography for Medicaid/Medicare breast cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0107-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doubeni CA, Field TS, Ulcickas Yood M, Rolnick SJ, Quessenberry CP, Fouayzi H, Gurwitz JH, Wei F. Patterns and predictors of mammography utilization among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2006;106:2482–2488. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duffy CM, Clark MA, Allsworth JE. Health maintenance and screening in breast cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elston Lafata J, Simpkins J, Schultz L, Chase GA, Johnson CC, Yood MU, Lamerato L, Nathanson D, Cooper G. Routine surveillance care after cancer treatment with curative intent. Med Care. 2005;43:592–599. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163656.62562.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field TS, Doubeni C, Fox MP, Buist DS, Wei F, Geiger AM, Quinn VP, Lash TL, Prout MN, Yood MU, Frost FJ, Silliman RA. Under utilization of surveillance mammography among older breast cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:158–163. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0471-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geller BM, Kerlikowske K, Carney PA, Abraham LA, Yankaskas BC, Taplin SH, Ballard-Barbash R, Dignan MB, Rosenberg R, Urban N, Barlow WE. Mammography surveillance following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;81:107–115. doi: 10.1023/A:1025794629878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz ML, Donohue KA, Alfano CM, Day JM, Herndon JE, Paskett ED. Cancer surveillance behaviors and psychosocial factors among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Cancer and Leukemia Group B 79804. Cancer. 2009;115:480–488. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan NF, Carpenter L, Watson E, Rose PW. Cancer screening and preventative care among long-term cancer survivors in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen MR, Urban N. The use of mammography by survivors of breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1713–1715. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehmer U, Harris J, Bowen DJ, Schroy PC., III Surveillance after colorectal cancer diagnosis in a safety net hospital. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:1138–1151. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper GS, Payes JD. Temporal trends in colorectal procedure use after colorectal cancer resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellison GL, Warren JL, Knopf KB, Brown ML. Racial differences in the receipt of bowel surveillance following potentially curative colorectal cancer surgery. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1885–1903. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elston Lafata J, Cole JC, Ben-Menachem T, Morlock RJ. Sociodemographic differences in the receipt of colorectal cancer surveillance care following treatment with curative intent. Med Care. 2001;39:361–372. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foley KL, Song EY, Klepin H, Geiger A, Tooze J. Screening colonoscopy among colorectal cancer survivors insured by Medicaid. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:205–211. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318209d21e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson GL, Melton LD, Abbott DH, Zullig LL, Ordin DL, Grambow SC, Hamilton NS, Zafar SY, Gellad ZF, Kelley MJ, Provenzale D. Quality of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3176–3181. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rolnick S, Alford SH, Kucera GP, Fortman K, Yood MU, Jankowski M, Johnson CC. Racial and age differences in colon examination surveillance following a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;2005:96–101. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rulyak SJ, Mandelson MT, Brentnall TA, Rutter CM, Wagner EH. Clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with colon surveillance among patients with a history of colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grunfeld E, Hodgson DC, Del Giudice ME, Moineddin R. Population-based longitudinal study of follow-up care for breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:174–181. doi: 10.1200/JOP.200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Surveillance testing among survivors of early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1074–1081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sankila R, Martinez C, Parkin DM, Storm H, Teppo L. Informed consent in cancer registries. Lancet. 2001;357:1536. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beskow LM, Sandler RS, Weinberger M. Research recruitment through US central cancer registries: balancing privacy and scientific issues. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1920–1926. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. Chicago, IL: American Joint Committee on Cancer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newcomb PA, Love RR, Phillips JL, Buckmaster BJ. Using a population-based cancer registry for recruitment in a pilot cancer control study. Prev Med. 1990;19:61–65. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugarman J, Regan K, Parker B, Bluman LG, Schildkraut J. Ethical ramifications of alternative means of recruiting research participants from cancer registries. Cancer. 1999;86:647–651. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<647::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pakilit AT, Kahn BA, Petersen L, Abraham LS, Greendale GA, Ganz PA. Making effective use of tumor registries for cancer survivorship research. Cancer. 2001;92:1305–1314. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1305::aid-cncr1452>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogerino A, Grant LL, Wilcox H, III, Schmitz KH. Geographic recruitment of breast cancer survivors into community-based exercise interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1413–1420. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819af871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boehmer U, Clark M, Glickman M, Timm A, Sullivan M, Bradford J, Bowen DJ. Using cancer registry data for recruitment of sexual minority women: successes and limitations. J Women's Health. 2010;19:1289–1297. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pal T, Rocchio E, Garcia A, Rivers D, Vadaparampil S. Recruitment of black women for a study of inherited breast cancer using a cancer registry-based approach. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;15:69–77. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly BJ, Fraze TK, Hornik RC. Response rates to a mailed survey of a representative sample of cancer patients randomly drawn from the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry: a randomized trial of incentive and length effects. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salsman JM, Segerstrom SC, Brechting EH, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA. Posttraumatic growth and PTSD symptomatology among colorectal cancer survivors: a 3-month longitudinal examination of cognitive processing. Psychooncology. 2009;18:30–41. doi: 10.1002/pon.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowery JT, Axell L, Vu K, Rycroft R. A novel approach to increase awareness about hereditary colon cancer using a state cancer registry. Genet Med. 2010;12:721–725. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f1366a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaiser K. The meaning of the survivor identity for women with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobsen GD, Jacobsen KH. Health awareness campaigns and diagnosis rates: evidence from National Breast Cancer Awareness Month. J Health Econ. 2011;30:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harvey JA, Strahilevitz MA. The power of pink: cause-related marketing and the impact on breast cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williamson JM, Jones IH, Hocken DB. How does the media profile of cancer compare with prevalence? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:9–12. doi: 10.1308/003588411X12851639106954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beskow LM, Sandler RS, Millikan RC, Weinberger M. Patient perspectives on research recruitment through cancer registries. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:1171–1175. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez AG, Miller AR, Gallion K, San Miguel de MS, Chalela P, Garcia AS. Testing three different cancer genetics registry recruitment methods with Hispanic cancer patients and their family members previously registered in local cancer registries in Texas. Community Genet. 2008;11:215–223. doi: 10.1159/000116882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]