Abstract

The goal of this study was to apply temperature-mediated heteroduplex analysis using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography to identify pyrazinamide (PZA) resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates and simultaneously differentiate between M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis. Features that contributed to an optimal assay included the use of two different reference probes for the pncA gene targets from wild-type M. tuberculosis and wild-type M. bovis, optimization of the column temperature, increasing the starting concentration of the elution buffer, and reducing the rate of elution buffer increase (slope). A total of 69 strains were studied, including 48 wild-type M. tuberculosis strains (13 were PZA-resistant strains) and 21 M. bovis strains (8 were BCG strains). In all isolates tested, wild-type M. tuberculosis generated a single-peak pattern when mixed with the M. tuberculosis probe and a double-peak pattern with the M. bovis probe. In contrast, all M. bovis isolates generated a double-peak pattern when mixed with the M. tuberculosis probe and a single-peak pattern with the M. bovis probe. PZA-resistant mutant M. tuberculosis isolates generated characteristic patterns that were easily distinguishable from both wild-type M. tuberculosis and M. bovis isolates. Chromatographic patterns generated by the two reference probes allowed the rapid detection of PZA resistance with the simultaneous ability to distinguish between M. tuberculosis and M. bovis. This approach may allow the detection of drug resistance-associated mutations, with potential application to clinical and epidemiological aspects of tuberculosis control.

Pyrazinamide (PZA) is a first-line drug for the treatment of tuberculosis (3). PZA appears to act on semidormant tubercle bacilli that are unaffected by any other antituberculosis drug (11). In combination with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol, it allows shortening of the treatment period from 18 to 6 months (2, 25). Whereas resistance to PZA is rare in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, almost all strains of Mycobacterium bovis are naturally resistant (13, 28). PZA is a prodrug that requires activation to its toxic form, pyrazinoic acid, a process mediated by pyrazinamidase (Pzase), an enzyme produced by mycobacterial species (29). The correlation between PZA resistance and Pzase activity is supported by the demonstration of loss of this activity in resistant isolates (18, 32).

The genetic basis for PZA resistance involves mutation within the pncA gene, which encodes Pzase activity (20, 28). Although cases of PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates with no pncA mutations have been reported, mutations of pncA and its putative promoter remain the major mechanism of PZA resistance (15, 20). Over 40 different mutations in either the pncA structural gene or its putative promoter associated with PZA resistance in M. tuberculosis have been described. The changes are either mutations that involve substitution of nucleotides or mutations in the form of nucleotide insertions or deletions (15, 20, 27). In contrast, the natural resistance to PZA demonstrated by M. bovis strains is uniformly due to a unique single-point mutation (C169G) in pncA. This mutation involves the replacement of histidine (CAC) with aspartic acid (GAC), leading to the production of inactive enzyme (26, 28).

Susceptibility testing to detect PZA resistance has recently received increased attention for a number of reasons, including the important role of PZA in shortening the time course for treatment of tuberculosis and the recent recognition of PZA-monoresistant strains of M. tuberculosis (9), the increasing frequency of tuberculosis infections following intravesical instillation of the naturally PZA-resistant M. bovis BCG strain for the treatment of superficial bladder cancer (1, 17, 19), and the increasing incidence of zoonotic tuberculosis in developing countries due to naturally PZA-resistant M. bovis (6, 16, 24).

Conventional mycobacterial susceptibility testing for PZA is dependent on growth of the organism in the presence of the drug. This technique is both time-consuming and potentially unreliable due to the poor growth of M. tuberculosis in the highly acidic medium required for PZA activity (7, 12). Automated testing systems, such as the BACTEC 460TB and BACTEC MGIT 960 systems, are more sensitive than conventional testing but require from 8 to 12 days to determine antibacterial susceptibility and have the potential for cross-contamination (12, 14, 31).

Genotypic assays for the detection of drug resistance have been applied to both cultured isolates and direct patient specimens. These include amplification techniques, DNA sequence analysis, PCR-single-strand conformation polymorphism electrophoresis, and structure-specific cleavage and DNA probe detection assays, all of which are capable of detecting mutations associated with drug resistance (8, 22, 30).

Temperature-mediated heteroduplex analysis (TMHA) using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) was originally applied to the detection of specific gene polymorphisms (21). The technology was recently applied to the detection of mutations associated with antituberculosis drug resistance (5). The technique utilized differential retention of homoduplex and heteroduplex DNAs under partial denaturing conditions for the identification of mutations in rpoB, katG, rspL, embB, and pncA that are responsible for rifampin, isoniazid, streptomycin, ethambutol, and PZA resistance, respectively. Additionally, a separate genetic element (oxyR) was utilized to differentiate between M. tuberculosis and M. bovis. Although the study demonstrated the feasibility of this approach for detecting resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents, detection of mutations in pncA was found to be problematic. The difficulty of detecting pncA mutations was attributed to the diverse natures of the mutations and their distribution throughout the gene and its putative promoter. It was proposed that the potential for highly stable DNA helices due to increased GC content within specific regions of the pncA gene represented a major technical challenge for TMHA methodology (5).

To overcome these difficulties, the analysis conditions of the TMHA assay were reengineered, and a second probe was added. In combination, these changes allowed the rapid identification of pncA mutations associated with PZA resistance and the ability to distinguish between the two closely related species of the complex, M. bovis and M. tuberculosis, using the same genetic target.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains.

Sixty-nine isolates of the M. tuberculosis complex were studied: 48 M. tuberculosis strains, 13 of which were PZA resistant, and 21 M. bovis strains, 8 of which were BCG strains. The PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates were obtained from either the Tuberculosis Diagnostic Laboratory of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (20) or the Tuberculosis Diagnostic Section of the Michigan Public Health Laboratory. The pncA genes from the 13 PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis strains had been sequenced and found to contain different mutations distributed throughout the pncA open reading frame, as well as the promoter region (Fig. 1). The study isolates included six reference M. bovis BCG strains (ATCC 35743, ATCC 35744, ATCC 35739, ATCC 35731, ATCC 35738, and ATCC 35748) from the CDC collection. Fifty clinical isolates were obtained from either Creighton University Medical Center (5 M. tuberculosis and 5 M. bovis isolates), CDC (4 M. bovis isolates), or the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) (4 M. bovis, 2 M. bovis BCG, and 30 M. tuberculosis isolates). Clinical isolates were identified as either M. tuberculosis or M. bovis as previously described (6, 32) using the standard biochemical reactions, including nitrate reduction, niacin accumulation, and Pzase activity. PZA susceptibility was previously determined for all isolates, with resistance defined by an MIC of >25 μg/ml using the proportion method with Middlebrook 7H10 medium (4). Two reference strains were used as probes in the TMHA study, M. tuberculosis H37Rv, obtained from UNMC, and M. bovis ATCC 19210, obtained from the CDC. Amplicons for use as probes in the assay were generated from these reference strains by using the primers described below. To determine the analytical specificity and cross-reactivity of our assay, six additional reference strains of nontuberculous Mycobacterium species were included: Mycobacterium avium (ATCC 25291), Mycobacterium intracellulare (ATCC 13950), Mycobacterium fortuitum (ATCC 6841), Mycobacterium chelonae (ATCC 35751), Mycobacterium kansasii (ATCC 35775), and Mycobacterium gordonae (ATCC 14470).

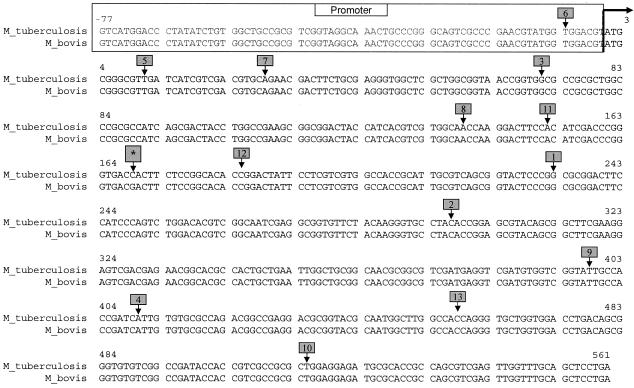

FIG. 1.

Alignment of pncA genes of wild-type M. tuberculosis and M. bovis and their putative promoters showing the positions of mutations in the 13 different mutant strains used in the study; mutant 1, G233A; mutant 2, C297G; mutant 3, del G71; mutant 4, A410G; mutant 5, T11C; mutant 6, T−7C; mutant 7, A29C; mutant 8, A139G; mutant 9, T398A; mutant 10, T515C; mutant 11, A152C; mutant 12, C185G; and mutant 13, C458A. *, unique mutation of M. bovis (C169G) that conveys natural PZA resistance. The arrow at the top indicates the start of the open reading frame.

Genomic-DNA isolation.

Genomic DNA was extracted from cultured isolates by the glass bead agitation method as previously described (23). The crude DNA extract was purified using the QIAmp Blood Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) according to protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Primer selection and PCR conditions.

Specific primers were designed using Oligo version 6.4 software (Molecular Biology Insight, Inc., Cascade, Colo.) to generate a 638-bp amplicon that included the entire pncA gene and its putative promoter. The sequence of the forward primer, AW-A3 (5′-GTCATGGACCCTATATCTGTGGCTGCCGCGTCG-3′), began at bp −77 upstream of the open reading frame, and that of the reverse primer, AW-A6 (5′-TCAGGAGCTGCAAACCAACTCGACGCTGG-3′), began at the stop codon (bp 561). The PCR assay was performed using 5 μl of template DNA (10 ng/μl) in a total reaction volume of 50 μl, including PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.4], 50 mM KCl); 0.1 mM (each) dATP, dGTP, dTTP, and dCTP; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.3 μM (each) primer; and 1.5 U of PlatinumTaq High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL-Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). Amplification was performed on a Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) Robocycler model 96 thermocycler starting with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles, each cycle consisting of a denaturation step at 95°C for 1 min, an annealing step at 64°C for 1 min, and an extension step at 72°C for 1 min. An additional extension step at 72°C for 7 min was performed after the last cycle. The amplicons were stored at 4°C until they were used.

Cloning of PCR products and sequence analysis.

PCR products from selected PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates were cloned directly following amplification using the standard protocol of the Original TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). Purified plasmids from selected colonies were screened for the correct insert by digestion with the endonuclease EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and analyzed by gel electrophoresis for the presence of an ∼600-bp product. Selected plasmids were sequenced at the Epply Molecular Biology Core Laboratory (UNMC, Omaha) using the universal M13 forward and reverse sequencing primers. The sequences were analyzed for the presence of mutations of interest by alignment against the wild-type M. tuberculosis sequence using MacVector sequence analysis software version 6.5 (Oxford Molecular Group, Inc., Campbell, Calif.).

TMHA assay.

The TMHA assay was performed using the commercial WAVE-DHPLC System (Transgenomics Inc. Omaha, Neb.). Since the hydrophobic matrix (polystyrene-divinylbenzene copolymer beads) of the WAVE-DNASep cartridge is electrostatically neutral and does not readily react with DNA, an ion-pairing reagent, triethylammonium acetate (buffer A), was used to adsorb DNA to the cartridge according to the manufacturer's protocol. An elution buffer composed of 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate in 25% acetonitrile (buffer B) was used to elute DNA based on size and/or sequence composition. Once eluted, the DNA was detected spectrophotometrically by UV absorption at 260 nm. The DNA molecules were analyzed for integrity by using nondenaturing conditions at a column temperature of 50°C, and they were analyzed for mutation detection by using partially denaturing conditions at a column temperature range of 52 to 70°C (21).

PCR product integrity analysis.

The PCR products of all isolates were analyzed for purity, specificity, and DNA concentration using the universal DNA-sizing gradient concentration program and a column temperature of 50°C with DHPLC. The phiX174 DNA ladder was used as the sizing marker. The sizing capability of the WAVE system allowed analysis of purity, and only those amplicons shown to generate a single uniform peak of the correct size were used for subsequent analysis.

DNA hybridization.

DNAs from the reference strains, M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 25618) and M. bovis ATCC 19210, were used for individual hybridization with each of the test isolates. In a total volume of 50 μl, equimolar ratios of test and reference DNA molecules were mixed together in the presence of polymerization inactivation buffer (5.0 mM EDTA, 60.0 mM NaCl, and 10.0 mM Tris [pH 8.0]). The mixture was heated to 95°C for 4 min and then left at room temperature for gradual cooling to 35°C over 45 min. For heteroduplex analysis, both homoduplex and heteroduplex molecules were generated by hybridization of the PCR product for each of the tested isolates with each of the reference DNA probes.

Heteroduplex analysis.

Following hybridization, mixtures of test isolates and reference probes were analyzed for pncA mutations using the partially denatured mode of the DHPLC. A variety of gradient concentrations were examined with different starting concentrations of buffer B at different rates of increase (slope), and a range of column temperatures from 64.8 to 66.8°C was evaluated. A modified gradient concentration program (Table 1) and a column temperature of 65.8°C were chosen for all subsequent mutation detection studies. A set of three mixtures of wild-type reference DNAs (both M. tuberculosis and M. bovis) and reference probes was included with each run of the test isolates. Each of the test isolates was analyzed at least three times on three successive days using three different PCR products from each template to test the reproducibility of the chromatographic patterns. The chromatographic patterns of test isolates were compared with those of reference isolates, and interpretations were made according to the proposed protocol (Table 2). Accordingly, any test isolate which generated a single-peak pattern with the M. tuberculosis reference probe and a double-peak pattern with the M. bovis reference probe was identified as wild-type M. tuberculosis, whereas any test isolate which generated a double-peak pattern with the M. tuberculosis reference probe and a single-peak pattern with the M. bovis reference probe was identified as M. bovis or BCG. Isolates that produced a double-peak pattern with both reference probes were identified as mutant strains of M. tuberculosis (PZA resistant). A double-peak pattern was defined as a negative deflection following a peak that created a visible trough between adjacent peaks. For each of the double-peaked chromatographic patterns, the distance between the peaks was recorded.

TABLE 1.

Modified gradient buffer concentrations for mutation detection within GC-rich pncA gene in comparison with universal gradient for mutation detection on WAVE system

| Step | Modified gradient for pncA gene mutation detection

|

Universal gradient for mutation detection

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (min) | Buffer (%)

|

Time (min) | Buffer (%)

|

|||

| Aa | Bb | A | Bc | |||

| Loading | 0.0 | 40 | 60 | 0.0 | 65 | 35 |

| Start gradient | 0.5 | 39 | 61 | 0.1 | 60 | 40 |

| Stop gradient | 6.2 | 29 | 71 | 16.1 | 28 | 72 |

| Start clean | 6.3 | 0d | 0d | 16.2 | 0d | 0d |

| Stop clean | 6.8 | 0d | 0d | 16.7 | 0d | 0d |

| Start equilibrate | 6.9 | 40 | 60 | 16.8 | 65 | 35 |

| Stop equilibrate | 7.8 | 40 | 60 | 18.0 | 65 | 35 |

Buffer A, ion-pairing reagent (triethylammonium acetate).

Buffer B, elution buffer (0.1 M triethylammonium acetate in 25% acetonitrile) with a slope of 1.2% increase per min.

Buffer B, with a slope of 2% increase per min.

Active cleaning step with 100% buffer D (75% acetonitrile).

TABLE 2.

Proposed protocol for identification of test isolates using two different reference probes for hybridization in TMHA-DHPLC assay

| Proposed identification of test isolate | TMHA-DHPLC peak pattern for reference probe:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis | M. bovis | |

| M. tuberculosis (wild type; PZA susceptible) | Single | Double |

| M. bovis (wild type; PZA resistant) | Double | Single |

| M. tuberculosis (mutant; PZA resistant) | Double | Double |

RESULTS

The specificity, purity, and concentration of PCR products from PZA-resistant mutant M. tuberculosis, wild-type M. tuberculosis, wild-type M. bovis, and M. bovis BCG were determined using the nondenaturing mode of the DHPLC system at a column temperature of 50°C. All tested isolates generated uniform products with identical relative retention times and approximate sizes of 600 bp compared to the PhiX 174 DNA ladder. The analytical specificity of the assay was demonstrated through testing of DNAs from six different reference species of nontuberculous mycobacteria which generated either variable small peaks consistent with nonspecific products or no product (data not shown).

Following optimization of the system, duplexes formed between PCR products of the tested isolates and each of the two reference probes were analyzed using the partially denatured mode of the system at the optimal buffer concentration gradient (Table 1) and column temperature (65.8°C).

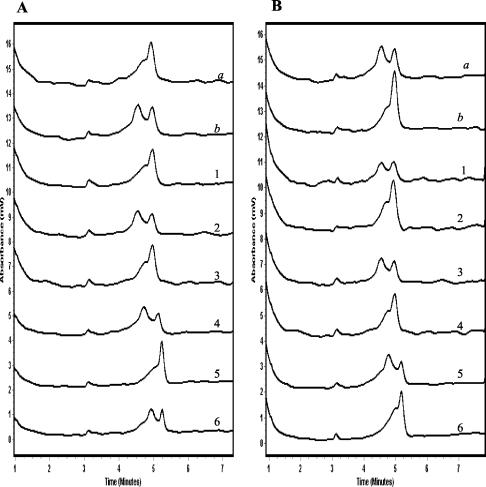

Chromatographic patterns produced by the wild-type PZA-susceptible isolates of M. tuberculosis demonstrated single-peak patterns when mixed with the M. tuberculosis reference probe and double-peak patterns when mixed with the M. bovis reference probe, as predicted (Fig. 2A). In contrast, M. bovis isolates produced double-peak patterns when mixed with the M. tuberculosis reference probe and single-peak patterns when mixed with the M. bovis reference probe (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

TMHA of pncA gene PCR products from reference control and test wild-type isolates using M. tuberculosis reference probe (A) and M. bovis reference probe (B). The chromatographic patterns a and b in each panel depict the wild-type reference control isolates of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, respectively, with the reference probes. Chromatographic patterns 1, 3, and 5 are representative wild-type M. tuberculosis test isolates, and patterns 2, 4, and 6 are representative M. bovis test isolates.

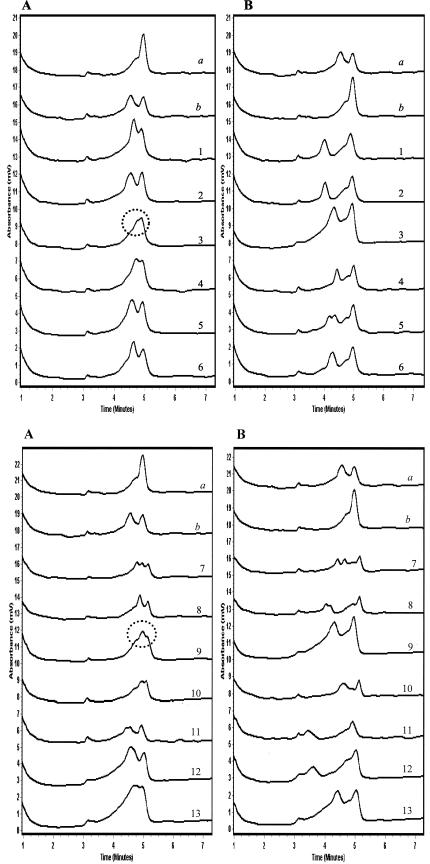

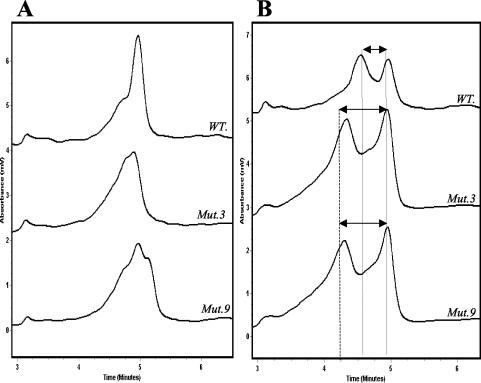

TMHA of the PZA-resistant pncA mutant M. tuberculosis strains generated the predicted chromatographic patterns with two peaks or more in 11 of the 13 isolates tested with both reference probes (Fig. 3). Two of the mutant isolates (mutant 3 and mutant 9) produced nonstandard but reproducible chromatographic patterns when they were mixed with the M. tuberculosis reference probe (Fig. 3). Further investigation showed that these chromatographic patterns contained distinct features that allowed their consistent recognition. In comparison with the single sharp peak generated by the wild-type PZA-susceptible M. tuberculosis isolates when mixed with the M. tuberculosis reference probe, mutant 3 produced a broad peak with a shoulder on one side while mutant 9 produced a double-shouldered peak (Fig. 4A). When mixed with the M. bovis reference probe, both mutants 3 and 9 generated the predicted double-peak patterns characteristic of all other mutant isolates. However, in comparison with chromatographic patterns generated by wild-type isolates, the mutant isolates demonstrated earlier elution of the first peak (heteroduplex DNA) than of the second peak (homoduplex DNA). This resulted in greater separation between the double peaks generated by the mutant isolates than between those generated by the wild-type isolates (Fig. 4B). When all of these observations were combined in the analysis, a protocol was developed that allowed the identification of all mutant isolates as distinct from wild-type M. tuberculosis isolates. Furthermore, since the chromatographic patterns for all M. bovis isolates were distinct, it was possible to distinguish them from either mutant or wild-type M. tuberculosis isolates.

FIG. 3.

TMHA of pncA gene PCR products from reference control and test mutant isolates using M. tuberculosis reference probe (panels A) and M. bovis reference probe (panels B). Chromatographic patterns a and b in each panel depict the wild-type reference control isolates of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, respectively, with the reference probes. Chromatographic patterns 1 to 13 depict the 13 test mutant isolates with each of the reference probes. All mutant isolates demonstrated the predicted double-peak patterns with both probes, with the exception of mutant 3 and mutant 9 (circled).

FIG. 4.

(A) TMHA of pncA gene PCR products of mutant isolates 3 and 9 with the M. tuberculosis reference probe. The chromatographs show the difference in shape between the patterns obtained by mutant isolates 3 (Mut.3) and 9 (Mut.9) and that of wild-type M. tuberculosis (WT.). (B) TMHA of pncA gene PCR products of mutant isolates 3 and 9 with the M. bovis reference probe. The differences in retention time between the double-peak patterns of mutant isolates 3 and 9 and that of wild-type M. tuberculosis are illustrated.

DISCUSSION

TMHA using DHPLC technology was originally applied to the rapid detection of DNA polymorphisms associated with genetic diseases and drug resistance (5, 21). The existence of specific pncA mutations associated with PZA resistance in the M. tuberculosis complex provided a means to both detect PZA resistance and distinguish M. tuberculosis from M. bovis. A naturally occurring polymorphism within pncA of M. bovis (C169G) has been used to differentiate the species from M. tuberculosis (26). The polymorphism within M. bovis strains is unique and different from all of the known acquired mutations of pncA of PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis. Therefore, a second probe was generated from the M. bovis pncA gene for use in combination with the wild-type M. tuberculosis probe. Differentiation between wild-type M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG strains and identification of PZA-resistant mutant strains of M. tuberculosis were achieved using a protocol to interpret chromatographic patterns produced by TMHA of the test isolates after mixing them with the two reference probes.

In order to identify the optimal assay conditions, an extended range of column temperatures and various gradient concentrations were studied. This resulted in a modification of the universal gradient concentration recommended by the manufacturer for mutation detection. The modification process included shortening the run time from 18 to <10 min by starting the gradient at a higher elution buffer concentration (61 rather than 40). This change was made based on the predicted retention time of analyzed duplexes according to size. In addition, the slope of elution buffer during the run was reduced from 2 to 1.2% per min. The modification process also included evaluation of a range of column temperatures, starting from the 64.8°C recommended by the system software and ranging up to 66.8°C in 0.1°C increments. The optimal column temperature was determined to be 65.8°C, since all higher and lower temperatures failed to induce the production of the predicted chromatographic patterns. These modifications improved the correlation among the predicted chromatographic patterns based on the theoretical helical structure of heteroduplexes of GC-rich sequences and the observed patterns. The essential outcome of these changes was that the previously cryptic mutations within the GC-rich sequence of pncA could be revealed.

The observed chromatographic patterns following TMHA of the wild-type isolates of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis (Fig. 2) were consistent with the predicted patterns on which the study was based and allowed the differentiation of the two closely related members of the M. tuberculosis complex.

Given the diversity of pncA mutations that convey PZA resistance, it was important to test mutations from within all regions of the coding sequence, as well as the promoter element. To test the clinical applicability of our assay, 13 different PZA-resistant mutant strains of M. tuberculosis were evaluated. Eleven of these mutant isolates generated the predicted chromatographic pattern when mixed with both reference probes, i.e., a double-peak pattern with clear demonstration of an intervening trough between the peaks. Two mutant M. tuberculosis isolates (mutant 3 and mutant 9) did not produce the standard double-peak pattern when mixed with the M. tuberculosis reference probe. These patterns were found to be highly reproducible when mutant isolates 3 and 9 were tested repeatedly. Review of the sequence showed that mutant isolates 3 and 9 had mutations in two different regions of pncA with high GC content. This was consistent with the original suggestion by Cooksey et al. that the difficulty in detecting pncA mutations was due to the presence of GC-rich sequences adjacent to the mutated nucleotides (5). The influence of the GC-rich region on the chromatographic pattern generated by mutations within such sequences was subsequently confirmed by analyzing two additional mutant isolates within GC-rich regions (C401T and G511A). Under the same optimized conditions, these mutants produced patterns similar to those of mutant isolate 9 (data not shown). We concluded that single-point mutations within or near GC-rich regions of pncA were unable to disrupt the helical structure of the heteroduplex DNA under the given conditions, rendering them indistinguishable from the homoduplex DNA. It was subsequently demonstrated that mutations within GC-rich regions could be uncovered through an optimal combination of both column temperature and gradient buffer concentration. Although the entire M. tuberculosis genome is GC rich (65% overall), certain regions have higher GC contents than others, which is expected to affect the melting points of the DNA molecules within those regions. Depending on where the boundaries are drawn for the calculation, the melting temperature is considerably higher; for example, the region surrounding the mutation of isolate 3 has a GC content of 82%.

Production of chromatographic peaks using TMHA-DHPLC (WAVE) technology is a function of temperature and the interaction between the DNA duplex and the cartridge matrix under given buffer gradients. It has been reported that the DNASep cartridge, under nondenaturing conditions, resolves the DNA fragment independently of sequence composition (10). However, in our laboratory, shouldered peaks have been observed with certain GC-rich sequences, even under nondenaturing conditions (D. R. Bastola, P. C. Iwen, and S. H. Hinrichs, unpublished data). We demonstrated that specific sequences with predicted secondary structure generated by these GC-rich sequences were responsible for these shouldered peaks. At higher temperatures and under the optimal gradient concentration used in the present study, the chromatographic patterns generated from mutant isolate mixtures that contain both homoduplex and heteroduplex populations were expected to contain double peaks, or at least shouldered peaks, that were distinguishable from those of wild-type isolates that contain only homoduplex populations.

Another important difference between the chromatographs produced by mutant isolates 3 and 9 and those produced by wild-type M. tuberculosis isolates was apparent when both were analyzed with the M. bovis reference probe. Mutants 3 and 9 produced chromatographic patterns with two peaks that were separated by a greater distance than that of wild-type isolates (Fig. 4B). This increase in peak separation was also seen in all other mutant isolates when they were mixed with the M. bovis probe. The generation of widely separated peaks was a function of an earlier elution time for the heteroduplex formed by the mutant DNA in comparison with the heteroduplex formed by the wild-type M. tuberculosis DNA. One explanation for this observation is that the mutant heteroduplexes have greater secondary structure than the wild-type heteroduplexes. This is due to the presence of two base pair mismatches in the mutant heteroduplex, one in the mutant DNA and one in the M. bovis reference probe, compared to the wild-type heteroduplexes, which have only a single base pair mismatch that is present in the M. bovis reference probe. The greater secondary structure in the mutant-isolate heteroduplexes is believed to result in its elution earlier than the wild-type heteroduplexes.

When the observed patterns from both reference probes were considered together, mutants 3 and 9 could be distinguished from wild-type M. tuberculosis isolates, a characterization that could not be made if only one probe was utilized in the analysis.

Under optimal conditions, mixed DNA populations (homoduplex and heteroduplex) produce two separate double-peak patterns. The first double peak represents the two different heteroduplex DNA populations, and the second double peak represents the two different homoduplex populations. Mixed DNA populations can produce two, three, or four peaks, depending on the type and position of the studied isolate mutation. The reaction conditions used for this study were optimized to recover all types of mutations. In isolate 7, the run temperature, gradient concentration, and gradient slope resulted in three peaks, while in other isolates, the same conditions differentiate only the larger double peaks of homoduplex and heteroduplex combinations.

Although rare, processing of a mixed culture of wild-type M. tuberculosis and M. bovis may generate a double-peak pattern with both reference probes. This pattern could be confused with that of a PZA-resistant mutant M. tuberculosis isolate. However, differentiation between the two cases is still possible based on the distance between the double peaks generated by the unknown isolate when mixed with the M. bovis reference probe (Fig. 4B). The distance between the two peaks of the wild-type M. tuberculosis strain (in the mixed culture) with the M. bovis reference probe is shorter than that of a PZA-resistant mutant M. tuberculosis isolate.

Inclusion of interpretive software to automate the interpretation of chromatographic patterns, especially those that need careful analysis, is under development and is expected to greatly assist the use of this new technology within the clinical setting.

Demonstration of the specificity of the present assay was also important, since cross-contamination with nontuberculous Mycobacterium species is a well-known problem in other standard culture-based automated assays (14, 31). Specificity was achieved through the use of specific primers that selectively amplify the pncA target only from the M. tuberculosis complex and not from nontuberculous mycobacteria (data not shown). The simultaneous screening for PZA resistance and identification of M. tuberculosis complex members was generally accomplished within 24 h of obtaining an isolate. Since PCR can be applied to direct patient specimens such as bronchial wash fluid (30), even faster analysis is feasible and should be further investigated.

Detection of clinically important drug-resistant subpopulations among predominantly susceptible bacilli represents a challenge for most genotypic assays used for drug resistance screening. We are investigating the sensitivity of our assay for the detection of PZA-resistant subpopulations in heterogeneous primary clinical isolates.

The ability to detect mutations within GC-rich sequences, essential for identification of PZA resistance, and the simultaneous ability to distinguish between the closely related Mycobacterium species M. tuberculosis and M. bovis significantly expand the utility of TMHA-DHPLC methodology for clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Iwen for helpful comments and review of the manuscript. Selected mycobacterial isolates were kindly provided by Steve Church, Michigan Department of Community Health Laboratories, and John Belle, Creighton University Medical Center.

This work was supported in part by an equipment grant from Transgenomic Inc. Amr M. Mohamed was supported by a research fellowship from the Egyptian government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aljada, I. S., J. K. Crane, N. Corriere, D. G. Wagle, and D. Amsterdam. 1999. Mycobacterium bovis BCG causing vertebral osteomyelitis (Pott's disease) following intravesical BCG therapy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2106-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian, R., M. Nagarajan, R. Balambal, S. P. Tripathy, R. Sundararaman, P. Venkatesan, C. N. Paramasivam, P. Rajasambandam, N. Rangabashyam, and R. Prabhakar. 1997. Randomised controlled clinical trial of short course chemotherapy in abdominal tuberculosis: a five-year report. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 1:44-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass, J. B., Jr., L. S. Farer, P. C. Hopewell, R. O'Brien, R. F. Jacobs, F. Ruben, D. E. Snider, Jr., G. Thornton, et al. 1994. Treatment of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in adults and children. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 149:1359-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canetti, G., W. Fox, A. Khomenko, H. T. Mahler, N. K. Menon, D. A. Mitchison, N. Rist, and N. A. Smelev. 1969. Advances in techniques of testing mycobacterial drug sensitivity, and the use of sensitivity tests in tuberculosis control programmes. Bull. W. H. O. 41:21-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooksey, R. C., G. P. Morlock, B. P. Holloway, J. Limor, and M. Hepburn. 2002. Temperature-mediated heteroduplex analysis performed by using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography to identify sequence polymorphisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex organisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1610-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosivi, O., J. M. Grange, C. J. Daborn, M. C. Raviglione, T. Fujikura, D. Cousins, R. A. Robinson, H. F. Huchzermeyer, I. de Kantor, and F. X. Meslin. 1998. Zoonotic tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis in developing countries. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:59-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies, A. P., O. J. Billington, T. D. McHugh, D. A. Mitchison, and S. H. Gillespie. 2000. Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic methods for pyrazinamide susceptibility testing with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3686-3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gingeras, T. R., G. Ghandour, E. Wang, A. Berno, P. M. Small, F. Drobniewski, D. Alland, E. Desmond, M. Holodniy, and J. Drenkow. 1998. Simultaneous genotyping and species identification using hybridization pattern recognition analysis of generic Mycobacterium DNA arrays. Genome Res. 8:435-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannan, M. M., E. P. Desmond, G. P. Morlock, G. H. Mazurek, and J. T. Crawford. 2001. Pyrazinamide-monoresistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:647-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecker, K. H., S. M. Green, and K. Kobayashi. 2000. Analysis and purification of nucleic acids by ion-pair reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 46:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heifets, L., and P. Lindholm-Levy. 1992. Pyrazinamide sterilizing activity in vitro against semidormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacterial populations. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 145:1223-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewlett, D., Jr., D. L. Horn, and C. Alfalla. 1995. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: inconsistent results of pyrazinamide susceptibility testing. JAMA 273:916-917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konno, K., F. M. Feldmann, and W. McDermott. 1967. Pyrazinamide susceptibility and amidase activity of tubercle bacilli. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 95:461-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leitritz, L., S. Schubert, B. Bucherl, A. Masch, J. Heesemann, and A. Roggenkamp. 2001. Evaluation of BACTEC MGIT 960 and BACTEC 460TB systems for recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens of a university hospital with low incidence of tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3764-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemaitre, N., W. Sougakoff, C. Truffot-Pernot, and V. Jarlier. 1999. Characterization of new mutations in pyrazinamide-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and identification of conserved regions important for the catalytic activity of the pyrazinamidase PncA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1761-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long, R., E. Nobert, S. Chomyc, J. van Embden, C. McNamee, R. R. Duran, J. Talbot, and A. Fanning. 1999. Transcontinental spread of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159:2014-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McParland, C., D. J. Cotton, K. S. Gowda, V. H. Hoeppner, W. T. Martin, and P. F. Weckworth. 1992. Miliary Mycobacterium bovis induced by intravesical bacille Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 146:1330-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, M. A., L. Thibert, F. Desjardins, S. H. Siddiqi, and A. Dascal. 1995. Testing of susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide: comparison of Bactec method with pyrazinamidase assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2468-2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan, M. B., and M. D. Iseman. 1996. Mycobacterium bovis vertebral osteomyelitis as a complication of intravesical administration of Bacille Calmette-Guerin. Am. J. Med. 100:372-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morlock, G. P., J. T. Crawford, W. R. Butler, S. E. Brim, D. Sikes, G. H. Mazurek, C. L. Woodley, and R. C. Cooksey. 2000. Phenotypic characterization of pncA mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2291-2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayanaswami, G., and P. D. Taylor. 2001. Improved efficiency of mutation detection by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography using modified primers and hybridization procedure. Genet. Test. 5:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piatek, A. S., S. Tyagi, A. C. Pol, A. Telenti, L. P. Miller, F. R. Kramer, and D. Alland. 1998. Molecular beacon sequence analysis for detecting drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:359-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plikaytis, B. B., R. H. Gelber, and T. M. Shinnick. 1990. Rapid and sensitive detection of Mycobacterium leprae using a nested-primer gene amplification assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1913-1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robles Ruiz, P., J. Esteban, and M. L. Guerrero. 2002. Pulmonary tuberculosis due to multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis in a healthy host. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:212-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Albisua, I., M. L. Vidal, G. Joya-Verde, F. del Castillo, M. I. de Jose, and J. Garcia-Hortelano. 1997. Tolerance of pyrazinamide in short course chemotherapy for pulmonary tuberculosis in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 16:760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scorpio, A., D. Collins, D. Whipple, D. Cave, J. Bates, and Y. Zhang. 1997. Rapid differentiation of bovine and human tubercle bacilli based on a characteristic mutation in the bovine pyrazinamidase gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:106-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scorpio, A., P. Lindholm-Levy, L. Heifets, R. Gilman, S. Siddiqi, M. Cynamon, and Y. Zhang. 1997. Characterization of pncA mutations in pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:540-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scorpio, A., and Y. Zhang. 1996. Mutations in pncA, a gene encoding pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase, cause resistance to the antituberculous drug pyrazinamide in tubercle bacillus. Nat. Med. 2:662-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Speirs, R. J., J. T. Welch, and M. H. Cynamon. 1995. Activity of n-propyl pyrazinoate against pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: investigations into mechanism of action of and mechanism of resistance to pyrazinamide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1269-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Telenti, A., P. Imboden, F. Marchesi, D. Lowrie, S. Cole, M. J. Colston, L. Matter, K. Schopfer, and T. Bodmer. 1993. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet 341:647-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tortoli, E., M. Benedetti, A. Fontanelli, and M. T. Simonetti. 2002. Evaluation of automated BACTEC MGIT 960 system for testing susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to four major antituberculous drugs: comparison with the radiometric BACTEC 460TB method and the agar plate method of proportion. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:607-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi, S. S., and S. G. Desai. 1987. Pyrazinamidase activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis—a test of sensitivity to pyrazinamide. Tubercle 68:221-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]