Abstract

Informed consent is the primary moral principle guiding the donation of human tissue for transplant purposes. When patients’ donation wishes are not known, family members making the decision about tissue donation should be provided with requisite information needed to make informed donation decisions. Using a unique dataset of 1,016 audiotaped requests for tissue obtained from 15 US tissue banking organizations, we examined whether the information provided to families considering tissue donation met current standards for informed consent. The results indicated that many elements of informed consent were missing from the donation discussions, including the timeframe for procurement, autopsy issues, the involvement of both for-profit and nonprofit organizations, and the processing, storage and distribution of donated tissue. A multiple linear regression analysis also revealed that nonwhites and family members of increased age received less information regarding tissue donation than did younger, white decision makers. Recommendations for improving the practice of obtaining consent to tissue donation are provided.

Keywords: Informed consent, Ethics, Tissue donation, Qualitative coding

Introduction

The donation and transplantation of human tissue offers medical relief to millions of Americans each year (American Association of Tissue Banks (AATB) 2012). The tissue donated by over 30,000 individuals may be employed in a variety of ways to improve and save lives (AATB 2012). Donated skin, for example, may be used as grafts to relieve pain, prevent fluid loss and stay infections in patients with severe burns or for reconstructive purposes (e.g., bladder support, breast reconstruction, eyelid repair; Heisel et al. 2000; Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation (MTF) 2005). Although prohibited in other countries (EU directive 95/34/EG), in the U.S. donated skin and/or adipose tissue is often also used for cosmetic purposes (e.g., penile enlargement, smoothing wrinkles). Donated bone, which can come from the hip, tibia or mandible, may be used to replace whole bones damaged by cancers, to repair deformities, or ground into a powder to secure dental implants (MTF 2005). Donated corneas give sight to the blind; tendons, ligaments and cartilage restore or improve mobility; and, heart valves repair or replace those ravaged by heart disease and/or deformity (Kent 2007; Rodrigue et al. 2003). When deemed unacceptable for transplantation, donated tissue may also be used for research and/or educational purposes. Over the last decade, however, the tissue banking industry has been the source of much contention, particularly in regard to the information provided to families considering donation.

Historically, informed consent to the donation of human organs, tissue and blood has been conceptualized as analogous to informed consent for research purposes (Alaishuski et al. 2008; Shaz et al. 2009; Sugarman et al. 2002; Truog 2008). Using this framework, families should be provided with basic elements of consent such as information regarding the purpose, benefits and risks associated with tissue donation, any alternatives to donation, confidentiality of the patient’s medical records, and the voluntary nature of donation and the right to withdraw consent (DHHS 2001). In addition, a joint statement issued by the National Donor Family Council (National Kidney Foundation (NKF) 2000) and professional organizations in the industry (American Association of Tissue Banks (AATB), Association of Organ Procurement Organizations (AOPO), and Eye Bank Association of America (EBAA)) outlines the specific elements of consent necessary for families to make truly informed donation decisions. These include, among other consent elements, descriptions of the processing, storage, distribution, and modification of the donated tissue. Table 1 maps the elements of informed consent set forth by the DHHS Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP 1998) with those proposed by the tissue banking industry’s professional associations. Because the benefits of donation are inherent to the discussion of the purposes of donation, these elements were considered equivalent. Additionally, as there are no alternatives to donation, this element is not applicable in this context. A number of additional consent elements specific to tissue donation proposed by the industry’s professional organizations are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Suggested elements of informed consent for tissue donation mapped to OHRP required elements of informed consent for research

| OHRP elements of consent for research | Suggested elements of consent for tissue donation | Total count (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Explanation of the purposes of the research | General description of the purposes (benefits) of donation | 482 (47.4) |

| Expected duration of participation | Timeframe for making a donation decision | 557 (54.8) |

| Timeframe for procurement of donated tissue | 270 (26.6) | |

| Description of the procedures to be followed | Explanations of the tissue donation process, including | |

| Tissue types requested | ||

| Bone | 633 (62.3) | |

| Corneaa | 539 (53.1) | |

| Whole eye | 520 (51.2) | |

| Other tissue | 452 (44.5) | |

| Skin | 424 (41.7) | |

| Tendons | 225 (22.1) | |

| Heart valves | 199 (19.6) | |

| Ligaments | 192 (18.9) | |

| Veins | 189 (18.6) | |

| Pericardium | 76 (7.5) | |

| Uses of donated tissue | ||

| Research | 579 (57.0) | |

| Education | 521 (51.3) | |

| Treatment of injury | 521 (51.3) | |

| Quality of life | 452 (44.5) | |

| Treatment of disease | 382 (37.6) | |

| Life-saving purposes | 256 (25.2) | |

| Need for the patient’s medical and social histories | ||

| Medical/social history | 630 (62.0) | |

| Release of medical records | 538 (53.0) | |

| Need for laboratory and communicable disease testing to determine medical suitability of the donated tissue | ||

| Suitability of tissues | 661 (65.1) | |

| Tests of suitability/compatibility | 557 (54.8) | |

| Recovery of donated tissue | ||

| General statement about procurement | 619 (60.9) | |

| Moving the patient | 342 (33.7) | |

| Processing of donated tissue (including the potential modification of donated tissue) | 264 (26.0) | |

| Storage of donated tissue | 189 (18.6) | |

| Distribution of donated tissue | 323 (31.8) | |

| Description of forseeable risks of participation | Explanation of the impact of the donation process on funeral and burial arrangements, including | |

| General comments about funeral arrangements | 580 (57.1) | |

| Ability to have an open casket | 553 (54.4) | |

| Delay in funeral arrangements | 287 (28.3) | |

| Cremation | 240 (23.7) | |

| Explanation of the impact of the donation process on the patient’s appearance, specifically | ||

| Appearance of patient | 473 (46.6) | |

| Mutilation of patient | 133 (13.1) | |

| Patient treated with respect | 283 (27.9) | |

| Description of forseeable benefits of participation | See explanation of the purpose (above) | N/A |

| Disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures | There are no alternatives to donation | N/A |

| Description of how the confidentiality of identifying records/materials will be maintained | Description of how patients’ medical records and family’s decision will be kept confidential | 305 (30.0) |

| Explanation of whom to contact with questions | Description of tissue bank | |

| Name of tissue bank | 768 (75.6) | |

| Contact information (telephone number) | 397 (39.1) | |

| Statement that participation is voluntary | Disclosure of family’s right not to donate | 382 (37.6) |

| Disclosure of family’s right to limit or restrict the use of donated tissue | 412 (37.6) | |

| Disclosure of family’s right to withdraw consent | 0 (0.0) | |

| Description of any additional costs for participating | Explanation that costs directly related to the evaluation, recovery, preservation and placement of donated tissue will not be charged to family | 522 (51.4) |

| Explanation that family will not be reimbursed for consent | 153 (15.1) |

Choice between cornea only and whole eye donation is offered to families; therefore, the counts for discussion of donation of cornea and whole eye are mutually exclusive

Table 2.

Additional consent elements for tissue donation

| Additional consent elements | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Description of any involvement of Medical Examiner and/or Coroner (including an explanation that an autopsy may be performed) | |

| Any mention of Medical Examiner and/or Coroner | 253 (24.9) |

| Any mention of an autopsy | 227 (22.3) |

| Explanation that transplantation may include reconstructive or aesthetic surgery | 296 (29.1) |

| Explanation that nonprofit and for-profit organizations may be involved in the process | |

| For-profit and not for profit companies (combined) | 269 (26.5) |

| Not for profit companies only | 221 (21.8) |

| For-profit companies only | 180 (17.7) |

| Authorization of access to patient’s medical records | 538 (53.0) |

| Family offered a copy of the written consent forma | 164 (27.1) |

| Family offered written material explaining tissue donationa | 3 (0.5) |

| Use of donated tissue abroad | 0 (0.0) |

Elements applicable only to surrogate decision makers agreeing to donation (n = 606)

Siegel et al.’s (2009) recent examination of the consent documents of 45 Organ Procurement Organizations (OPO) which also request the donation of tissue found that many of the “suggested key elements of informed consent” were missing from the OPOs’ informed consent forms. For instance, consent forms rarely provided information regarding the storage of donated tissue or family notification about tissue deemed unusable. Moreover, none of the consent documents offered information on the packaging and labeling of donated tissue. Other information that was commonly absent was the possible use of donated tissue outside the U.S., the modification of donated tissue, the appearance of the patient after donation, the families’ receipt of a copy of the informed consent document, and OPO contact information. The authors conclude that while certain items were often missing, the majority of the elements of informed consent recommended by the DHHS, NKF and industry groups were routinely found in the consent documents. They also note the inherent difficulties in full disclosure of all aspects of the tissue donation process, e.g., communicating the “morally relevant distinctions between ‘for profit’ and ‘nonprofit’” to grieving families and recommend continued dialogue over the informed consent elements relevant today. To date, however, there is no research examining what information families are actually provided during discussions about donation. The current study is the first to offer a comprehensive examination of the consent practices in tissue donation using a unique dataset of audiotape recorded requests for tissue.

Methods and measures

Tissue bank sample

Fifteen (N = 15) tissue banking organizations, representing geographic areas in 12 US states, were randomly selected to participate via letters of invitation. All agreed to collaborate as study sites. Collectively, these participating tissue banks service over 600 counties, with a total population of over 40,000,000 (Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients 2012).

Tissue donation is possible for patients who have died of cardiac arrest, both within and outside of the hospital, and tissues may be procured up to 48 h after the patient has died (Kent 2007). Thus, the number of tissue-eligible deaths each year far exceeds the number of organ-eligible deaths. Therefore, most requests for tissue donation are made by telephone; tissue banks routinely audiorecord all requests for quality assurance monitoring. Given the high volume of tissue requests made at each study site, participating tissue banks were randomly assigned data collection days each month. Data collection at each site comprised obtaining the audiorecordings of donation discussions made on specified data collection days in the 2-year period from February 2004 to 2006.

Surrogate decision maker and tissue requester samples

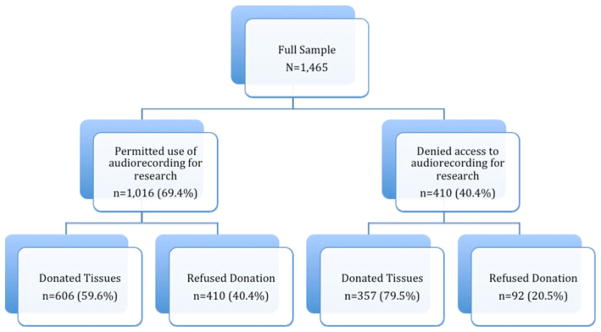

Family members making the decision to donate or not to donate tissues and tissue bank staff requesting donation, comprised our sample. Family decision makers were identified with the assistance of the participating tissue banks. We contacted family decision makers 2–3 months after the death of the patient to request an interview. The semi-structured family interview has been described in detail elsewhere (Siminoff et al. 2010). For the purposes of this study, only surrogate decision makers’ responses to 7 sociodemographic questions were of interest. The questions assessed decision makers’ sex, race, marital status, religious affiliation, age, education, and occupation (i.e., health related/not health related). Of the 1,465 family decision makers agreeing to participate in the study, 1,016 (69.4%)–606 (59.6%) of whom consented to donate tissue and 410 (40.4%) who did not—also permitted access to the audiorecordings for research purposes (449 (30.6%) denied access to the audiorecordings); the final sample comprised only those family decision makers allowing use of the audiorecorded donation discussions (N = 1,016). Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of the study sample.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study sample

One hundred fifty-six (n = 156) tissue requesters consented to participate in the research as well; all consenting requesters completed a brief sociodemographic survey capturing requester sex, race marital status, religious affiliation, age, education, experience and whether the requester had earned a health-related degree. The study was reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review boards and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data coding

Transcription and coding of the audiorecorded donation discussions was performed using the Siminoff Communication Content and Affect Program (SCCAP). The SCCAP was developed to code and analyze conversational data (Siminoff and Step 2011). The SCCAP was used to determine whether the suggested elements of informed consent were included in donation discussions. The consent elements used to guide this research are presented in Table 1. Trained coders listened to each recording and coded whether each consent element occurred during the request. Each element of consent was coded as present if either the tissue requester or surrogate decision maker made a statement or asked a question about the topic. Each of seven coders received extensive training in the use and application of the SCCAP over a period of 3 months. Inter-rater reliability, as assessed through percent agreement, ranged from 0.77 to 0.88 (Siminoff and Step 2011). Similarly high levels of inter-rater reliability have been demonstrated in SCCAP coding of oncological consultations (Siminoff et al. 2008).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the tissue requester and surrogate decision maker samples. Frequency counts and corresponding percentages summarize the occurrence of each element of informed consent within the audiorecorded donation discussions. Frequencies and percentages were also recorded for the occurrence of consent elements specific to tissue donation.1

A multiple linear regression was performed to identify the tissue requester and surrogate decision maker characteristics influencing the amount of information disclosed during donation discussions. Because the amount of information contained within each consent element varied considerably (e.g., explanation of the duration of participation includes two pieces of information while description of the procedures includes 26 pieces of information), each piece of information was weighted so that all pieces of information within each consent element summed to 10. Means and standard deviations were estimated for the total information disclosed for each consent element.

A global score of the total amount of information discussed (global discussion score) during the request was created by summing the individual scores for each consent element. The global score was regressed on decision maker and requester sociodemographics (e.g., sex, race, marital status, religious affiliation, health related occupation and/or degree, willingness to donate own tissue, donor status, age, education, and experience). Additionally, requests for tissue were nested within participating tissue requesters and tissue banks to control for both confounders in the analysis. We also controlled for the duration of the donation request as donation discussions with decision makers refusing donation were significantly shorter and included fewer consent elements than those held with decision makers who donated. Because of the variable’s distribution, a logarithmic transformation was performed to meet the assumption of linearity for the regression analysis. The number of missing values was small (175 of 15,240 observations; 1.1%), and a complete dataset was achieved through multiple imputation (Rubin 1987).

Results

Sample demographics

Table 3 summarizes the sociodemographic information for the tissue requesters and surrogate decision makers. Requesters were relatively young (M = 34.7 years, SD = 9.3 years), white (79.5%), and female (71.8%), with a mean education of 15.5 years (SD = 1.8). Approximately equal numbers of the tissue requesters identified themselves as either single (44.2%) or married (42.3%) and most self-reported either Protestant (40.4%) or Catholic (25.6%) religious affiliations. Slightly less than half of the participating tissue requesters held a degree in a health-related field (48.7%). The median length of job experience was 8.5 months (M = 17.0 months, SD = 22.1).

Table 3.

Sample demographics

| Characteristic | Surrogate decision maker total count (%) | Tissue requester total count (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 733 (72.2) | 112 (71.8) |

| Race | ||

| White | 846 (83.3) | 124 (79.5) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married/single | 75 (7.4) | 69 (44.2) |

| Married/cohabit | 345 (34.0) | 66 (42.3) |

| Divorced/separated | 95 (9.4) | 21 (13.5) |

| Widowed | 477 (47.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| Protestant | 511 (50.3) | 63 (40.4) |

| Catholic | 231 (22.7) | 40 (25.6) |

| Other | 138 (13.6) | 30 (19.2) |

| None | 135 (13.3) | 22 (14.1) |

| Health-related occupation/degree | ||

| Yes | 145 (14.3) | 76 (48.7) |

| Willing to donate own tissue | ||

| Yes | 780 (76.8) | – |

| Signed donor card/license marked “donor” | ||

| Yes | 550 (54.1) | – |

| Duration of donation discussion (minutes)a | 14.5 (14.6; Median, 8.7) | – |

| Age (years)a | 52.1 (13.5) | 34.7 (9.3) |

| Education (years)a | 13.9 (2.4) | 15.5 (1.8) |

| Experience (months)a | – | 17.0 (22.1; Median, 8.5) |

Values expressed as Mean (SD). Counts may not sum to 100% due to missing values

Decision makers were also mostly female (72.2%) and white (83.3%), but older (M = 52.1 years, SD = 13.5 years) and less well-educated (M = 13.9 years, SD = 2.4 years) than requesters. Approximately half were Protestant 511 (50.3%) and widowed (47.0%). Over three-quarters (76.8%) stated a willingness to donate their own tissue and 54.1% had a signed donor card. Overall, 59.6% (n = 606) of decision makers consented to donate tissues.

Information included in donation discussions

The mean scores for each element of informed consent and the global score representing the average amount of information disclosed during tissue requests are presented in Table 4. The mean global score was 34.6 (SD = 22.7), slightly more than a third of the maximum possible score of 90 (e.g., a maximum possible score of 10 for each of 9 consent elements). Information on how to contact the tissue bank had the highest individual element score with a mean value of 6.6 (SD = 2.8), while descriptions of the confidentiality of patients’ private information had the lowest score of 2.6 (SD = 2.5).

Table 4.

Summary of OHRP consent element and total information discussed scores

| OHRP elements of informed consent | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Explanation of the purposes of the research | 4.7 (5.0) |

| Expected duration of participation | 4.1 (3.8) |

| Description of the procedures to be followed | 4.0 (3.1) |

| Description of forseeable risks of participation | 3.6 (3.0) |

| Description of forseeable benefits of participation | N/A |

| Disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures | N/A |

| Description of how the confidentiality of identifying records/materials will be maintained | 3.0 (4.6) |

| Explanation of whom to contact with questions | 6.6 (2.8) |

| Statement that participation is voluntary | 2.6 (2.5) |

| Description of any additional costs for participating | 3.3 (3.4) |

| Additional elements for tissue donation | 2.7 (2.7) |

| Global Information Discussed Score | 34.6 (22.8) |

Each consent element had a possible maximum score of 10, with a maximum global score of 90

The single piece of information most commonly included in donation discussions was the name of the tissue bank (Table 1). This information was found in 92.4% of requests. A number of informational items were found in approximately half to two-thirds of the donation discussions including the need for testing to determine medical suitability (65.1%), disclosure of the families’ right not to donate (62.4%), a general discussion of the procurement process (60.9%), general comments about funeral arrangements (57.1%), the ability to have an open casket funeral (54.4%), and the timeframe for making a donation decision (54.8%). Information included in less than half of the tissue requests pertained to the processing (26.0%), storage (23.6%), and distribution (31.8%) of the donated tissue; the potential involvement of for-profit and not-for-profit companies (26.5%); the potential use of the donated tissue for reconstructive and/or cosmetic purposes (29.1%); and the families’ right to place restrictions on the use of the donated tissue (37.6%). Neither discussion of the potential use of the donated tissue in foreign countries (i.e., abroad) nor disclosure of the families’ right to withdraw consent, were found in any of the examined requests. Finally, only 27.1% of consenting families were offered a copy of the written consent form.

Factors influencing the information discussed

A multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify surrogate decision maker and tissue requester sociodemographic variables (e.g., sex, race, marital status, religious affiliation, health related occupation and/or degree, willingness to donate own tissue, donor status, age, education, and experience) predicting the amount of information discussed during the donation conversation. Because participating requesters made multiple requests for tissue at each tissue bank, both variables representing the tissue requesters and the tissue banks were controlled for in the analysis. Additionally, tissue requesters spent an average of 14.5 min (SD = 14.6 min; Median = 8.7 min) discussing the option of tissue donation with surrogate decision makers. However, significantly more time was spent discussing donation (21.9 min, SD = 14.6, vs. 3.5 min, SD = 3.6) with decision makers who consented to tissue donation than with those who decided not to donate. Therefore, we also controlled for the duration of the donation discussion.

The results of the analysis are presented in Table 5. A positive relationship between the duration of the donation conversation and the global information discussed was revealed; specifically, the amount of information discussed during the request increased by 9.4 points (Standard Error (SE) = 0.37, p <0.0001) for each unit increase of time on the logarithmic scale. The age and race of the surrogate decision maker each were also related to the global discussion score. The global score decreased by 1.6 points (SE = 0.45, p <0.0001) for every 10 years of the surrogate decision maker’s age. Finally, white decision makers discussed 4.8 points more information with tissue requesters than non-whites (SE = 1.5, p <0.01). There were no significant relationships between the global discussion score and any of the tissue requesters’ sociodemographic variables.

Table 5.

Results of multiple regression analysis

| Variable | β | Standard error | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of donation discussiona | 9.3 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Decision maker characteristics | |||

| Sex (female) | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.09 |

| Race (Nonwhite) | 4.5 | 1.4 | <0.01 |

| Marital status (widowed) | 0.56 | ||

| Never married | −2.1 | 2.1 | |

| Married | −1.3 | 1.2 | |

| Divorced | −0.41 | 1.8 | |

| Religious beliefs (none) | 0.94 | ||

| Protestant | 0.56 | 1.6 | |

| Catholic | 1.1 | 1.8 | |

| Other | 0.20 | 2.0 | |

| Health-related occupation (yes) | 0.46 | 1.5 | 0.76 |

| Age | −0.19 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Education | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.16 |

| Tissue requester characteristics | |||

| Sex (female) | 0.79 | 1.5 | 0.60 |

| Race (Nonwhite) | −0.02 | 1.4 | 0.99 |

| Marital status (divorced) | 0.13 | ||

| Single | −3.4 | 1.9 | |

| Married | −3.2 | 1.7 | |

| Religion (none) | 0.40 | ||

| Protestant | 2.6 | 2.0 | |

| Catholic | 3.3 | 2.2 | |

| Other | 2.4 | 2.1 | |

| Health-related degree (yes) | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.16 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.92 |

| Education | −0.10 | 0.38 | 0.79 |

| Experience | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.70 |

Variable was logarithmically transformed to meet assumption of linearity; referent group indicated in parentheses

These analyses are restricted to data from family decision makers consenting to the use of the audio-recorded donation discussion (N = 1,016). It is possible that somewhat different results may have been obtained had the data from the 449 (30.6%) family decision makers who denied access to the audiorecordings been included in the analysis. Indeed, significant differences were found in the sociodemographic characteristics of decision makers permitting as compared to those denying access to the recorded discussions. For example, decision makers denying access were significantly more likely to have consented to donation (79.5 vs. 59.6%; p <0.001) and to be of Hispanic heritage (5.8 vs. 3.0%; p = 0.02), as compared to decision makers allowing use of the recorded conversations. Conversely, individuals withholding permission for use of the audiorecordings were less likely to report working in a health-related field (10.1 vs. 14.6%; p = 0.02). Decision makers denying access were also slightly, but significantly younger than those who permitted use for research purposes (mean age 50.3 years (standard deviation = 13.2) versus 52.1 years (SD = 13.5); p <0.01). No other statistically significant differences were found in the demographic characteristics of the two groups (e.g., sex, race, education, religion, willingness to donate own tissue, willingness to donate own organs, status as a registered organ donor).

Significant differences were also found between decision makers consenting to tissue donation and those refusing to donate within the main study sample (N = 1,016). Consistent with past research examining consent to organ donation (Brown et al. 2010), more nondonors were of minority descent (30.5 vs. 8.2%; p <0.001). Additionally, fewer nondonors expressed a willingness to donate their own tissues (56.2 vs. 91.8%; p <0.001) or organs (59.3 vs. 92.5%; p <0.001) and fewer nondonors held a signed organ donor card (34.8 vs. 66.5%; p <0.001), as compared to decision makers who consented to donate tissue. As noted previously, nondonors also held significantly shorter conversations with tissue bank staff than did donors. Thus, the duration of the donation discussion was included as a covariate in the linear regression to account for the observed differences between donors and nondonors. Given the findings of the subgroup analyses, however, the estimates produced in the statistical analyses may contain some degree of bias.

Discussion

In the United States, the practice of organ and tissue donation is firmly grounded in the bioethical principle of autonomy. Autonomy is based on the premise that individuals are capable of and have a right to self-determination or “self-rule” (Beauchamp and Childress 2009, p. 99). Although the number of individuals documenting a desire to become a posthumous organ donor is on the rise, it is estimated that only 40% of the U.S. population are enrolled on a state organ donor registry and only about 70% have communicated this desire to others (Donate Life America 2011; Gallup 2005). Hence, the wishes of most potential donors are either unknown or not documented and the decision regarding donation often reflects the wishes of a surrogate decision maker. While research demonstrates that most surrogates consider potential donors’ character and known or implied attitudes about donation in the decision making process (Siminoff and Lawrence 2002), some do not. Indeed, a minority of surrogates decide against donation even when the patient’s donation wishes are documented (Christmas et al. 2008). Yet, when surrogate decision makers know that the patient wanted to donate or the patient is a registered donor, they are significantly more likely to donate (Siminoff et al. 2007). For all these reasons, First Person Consent laws and the trend toward increased registration as a donor are welcomed changes.

For family decision makers to make an informed choice, especially about tissue donation, which remains less familiar to the public than organ donation (Rodrigue et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2006), decision makers must have a firm understanding of the processes, risks, and benefits associated with donation. These results indicate that increased efforts are needed to ensure surrogate decision makers have the requisite information that DHHS and others have deemed necessary to making informed decisions about donation. For example, information regarding the timeframe for procurement, autopsy issues, the involvement of both for-profit and nonprofit organizations, and the processing, storage and distribution processes were found in less than fifty percent of the discussion about donation. Although we cannot say with precision the extent to which the information conveyed during the requests deviates from the OPOs’ consent documents or standard operating procedures, previous research has identified many of these same elements as missing from organizational consent forms (Siegel et al. 2009). Yet, as discussed previously, these topics and others are considered critical elements of informed consent to tissue donation by industry standards as well as by the ethical principles of informed consent for research. More importantly, past research has demonstrated the importance of these topics and others to families’ tissue donation decision making process (Siminoff et al. 2010). Additionally, few families were offered a copy of the consent form and fewer still were provided with additional written information about tissue donation. Clearly, tissue request staff are in need of continued training in the conduct of providing informed consent to families presented with the option of donation.

Admittedly, ensuring every potential donor family is provided with all of the information comprising informed consent is a difficult, if not impossible, task. First, tissue request staff are charged with the already difficult task of contacting grieving families about the option of donating their family member’s body parts. Second, 40.4% of decision makers in this sample refused donation. Consent discussions with these families were of significantly shorter duration than those with families agreeing to donate and, to no surprise, contained fewer elements of informed consent. Additionally, the results of the linear regression analysis suggest that donation conversations with younger, white surrogate decision makers include more elements of informed consent than do conversations with older decision makers or minorities (e.g., African Americans, Asians, Hispanics/Latinos). However, request staff should strive to provide the same quality and quantity of information to all families, regardless of whether they ultimately agree to donate or decline. A potential solution to providing families with donation-related information and improving understanding of the myriad of issues related to tissue donation is the creation and dissemination of educational materials to all families approached about donation.

The collected data did not allow for the identification of the speaker who initiated the conversation about the various informational topics constituting elements of informed consent. That is, it is not known whether tissue requesters offered the information about each of the elements under investigation or families prompted their discussion. It is possible that some elements were discussed only because surrogate decision makers made a statement or asked a question about the topic. Future research in this area should attempt to link conversational players with the information discussed.

It is also worth noting that this study examined only the specific information discussed during requests for tissue donation. Future research should also examine surrogate decision makers’ understanding of the information provided during requests and identify the specific information surrogate decision makers feel they need to make decisions about donation. Ideally, such research would also identify ethnic, cultural, and generational differences in families’ information needs. An understanding of these needs would allow informed consent discussions to meet the three standards of disclosure—professional practice, reasonable person, and subjective (Beauchamp and Childress 2009). Disclosure of expert information about tissue donation, in lay terms, meets the professional practice standard. The reasonable person standard requires disclosure of information that the average, competent person would need to make a decision about donation; the subjective standard acknowledges that individuals’ information needs differ and suggests that disclosure should be tailored to the specific individual. Using these standards as a gauge means that families would be provided with technical information about tissue donation as well as information research has identified as critical to most families’ decision whether or not to donate. Additional information about donation could then be provided on an as needed basis. Therefore, we endorse Siegel et al.’s (2009) call for continued research and discussion about the elements of informed consent relevant to today’s society and necessary for informed decision making to tissue donation.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grant #R01 HS-13152 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). AHRQ played no role in the study’s design, conduct or reporting.

Footnotes

This analytical approach was chosen over a comparison of the information discussed during donation conversations by donation outcome (i.e., consented vs. refused) because of the nature of the subject under investigation. That is, the principles of informed consent demand that all surrogate decision makers be provided with the information deemed requisite for informed decision making and that the amount of information discussed should not be dependent upon the donation decision.

References

- Alaishuski LA, Grim RD, Domen RE. The informed consent process in whole blood donation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(6):947–951. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-947-TICPIW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Tissue Banks. [Accessed 20 Jan 2012];2012 http://www.aatb.org/content.asp?contentie=453.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JL. Principles of biomedical ethics. 6. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CVR, Foulkrod KH, Dworacqyk S, Thompson K, Elliot E, Cooper H, Coopwood B. Barriers to obtaining family consent for potential organ donors. J Trauma. 2010;68(2):447–451. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181caab8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christmas AB, Burris GW, Bogarg TA, Sing RF. Organ donation: family members NOT honoring patient wishes. J Trauma. 2008;65(5):1095–1097. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160e1f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donate Life America. [Accessed 22 Jan 2012];National donor designation report card. 2011 http://donatelife.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/DLA-Report-BKLT-30733-2.pdf.

- Heisel W, Katches M, Kowalczyk L. The body brokers -Part 2: Skin merchants. [Accessed 26 Feb 2012];2000 http://www.lifeissues.net/writers/kat/org_01bodybrokerspart2.html.

- Kent B. Tissue donation and the attitudes of healthcare professionals. In: Sque MRJ, editor. Organ and tissue donation: an evidence base for practice. Open University Press; GBR: 2007. pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Muskuloskeletal Transplant Foundation. [Accessed 7 May 2011];Donation FAQ’s. 2005 http://www.mtf.org/donor/faq.html.

- National Kidney Foundation. [Accessed 3 May 2011];National Donor Family Council Executive Committee: Informed Consent Policy for Tissue Donation. 2000 http://www.kidney.org/transplantation/donorFamilies/infoPolicyConsent.cfm.

- Rodrigue JR, Scott MP, Oppenheim AR. The tissue donation experience: a comparison of donor and nondonor families. Prog Transp. 2003;13(4):258–264. doi: 10.1177/152692480301300404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. [Accessed 20 Jan 2012];Program and OPO specific reports. 2012 http://www.ustransplant.org/csr/archives/facilities.aspx?

- Shaz BH, Demmons DG, Hillyer CD. Critical evaluation of informed consent forms for adult and minor aged whole blood donation used by United States blood centers. Transfusion. 2009;49:1136–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009. 02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel A, Anderson MW, Schmidt TC, Youngner SJ. Informed consent to tissue donation: policies and practice. Cell Tissue Bank. 2009;10(3):235–240. doi: 10.1007/s10561008-9115-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Lawrence RH. Knowing patients’ preferences about organ donation: does it make a difference? J Trauma. 2002;53(4):754–760. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200210000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Step M. A comprehensive observational coding scheme for analyzing instrumental, affective and relational communication in healthcare contexts. J Health Commun. 2011;16(2):178–197. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.535109. doi:10(1080/10810730)2010535109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Mercer MB, Graham G, Burant C. The reasons families donate organs for transplantation: implications for policy and practice. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):969–978. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000205220.24003.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Step M, Rose J. Coding conversational data: approaches, challenges, and a new system for coding data. Paper presented at the international psycho-oncology society (IPOS) 10th world congress; Madrid, Spain. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Traino HM, Gordon N. Determinants of family consent to tissue donation. J Trauma. 2010;69(4):956–963. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d8924b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman J, Kurtzberg J, Box TL, Horner RD. Optimization of informed consent for umbilical cord blood banking. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(6):1642–1646. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Gallup Organization. [Accessed 22 Jan 2012];National survey of organ donation attitudes and behaviors. 2005 ftp://ftp.hrsa.gov/organdonor/survey2005.pdf.

- Truog RD. Consent for organ donation—balancing conflicting ethical obligations. N Eng J Med. 2008;358(12):1209–1211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0708194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed 26 Feb 2012];Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). Informed consent checklist - basic and additional elements. 1998 http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/consentckls.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed 10 May 2011];Office of Inspector General. Informed consent in tissue donation: expectations and realities. 2001 http://www.oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-00-00440.pdf.

- Wilson P, Sexton W, Singh A, Smith M, Durham S, Cowie A, Fritschi L. Family experiences of tissue donation in Australia. Prog Transp. 2006;16(1):52–56. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]