Abstract

The molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii was investigated in the medical-surgical intensive care unit (ICU) of a university hospital in Italy during two window periods in which two sequential A. baumannii epidemics occurred. Genotype analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of A. baumannii isolates from 131 patients identified nine distinct PFGE patterns. Of these, PFGE clones B and I predominated and occurred sequentially during the two epidemics. A. baumannii epidemic clones showed a multidrug-resistant antibiotype, being clone B resistant to all antimicrobials tested except the carbapenems and clone I resistant to all antimicrobials except ampicillin-sulbactam and gentamicin. Type 1 integrons of 2.5 and 2.2 kb were amplified from the chromosomal DNA of epidemic PFGE clones B and I, respectively, but not from the chromosomal DNA of the nonepidemic clones. Nucleotide analysis of clone B integron identified four gene cassettes: aacC1, which confers resistance to gentamicin; two open reading frames (ORFs) coding for unknown products; and aadA1a, which confers resistance to spectinomycin and streptomycin. The integron of clone I contained three gene cassettes: aacA4, which confers resistance to amikacin, netilmicin, and tobramycin; an unknown ORF; and blaOXA-20, which codes for a class D β-lactamase that confers resistance to amoxicillin, ticarcillin, oxacillin, and cloxacillin. Also, the blaIMP allele was amplified from chromosomal DNA of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I. Class 1 integrons carrying antimicrobial resistance genes and blaIMP allele in A. baumannii epidemic strains correlated with the high use rates of broad-spectrum cephalosporins, carbapenems, and aminoglycosides in the ICU during the study period.

Acinetobacter baumannii is a glucose-nonfermentative gram-negative coccobacillus that is widely distributed in the hospital environment and is an important opportunistic pathogen responsible for a variety of nosocomial infections, comprising bacteremia, urinary tract infection, secondary meningitis, surgical-site infection, and nosocomial and ventilator-associated pneumonia, especially in intensive-care-unit (ICU) patients (4, 6, 7, 10, 15, 16, 24, 29). Extensive use of antimicrobial chemotherapy within hospitals has contributed to the emergence and increase in the number of A. baumannii strains resistant to a wide range of antibiotics, including broad-spectrum beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones (4, 7, 10, 15, 24, 28). In recent years, several outbreaks of nosocomial infections caused by carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii have been documented (3, 6, 10, 16, 25). Because of the multiple antibiotic resistance exhibited by A. baumannii, nosocomial infections caused by this organism are difficult to treat. These therapeutic difficulties are coupled with the fact that these bacteria have a significant capacity for long-term survival in the hospital environment, thus favoring the transmission between patients, either via human reservoirs or via inanimate materials (3, 4, 6, 10). Studies of antibiotic resistance mechanisms in Acinetobacter spp. have demonstrated the presence of specific genes located on integrons (8, 11, 12, 21). These are genetic elements consisting of a gene encoding an integrase (intI) flanked by a recombination site, attI, where mobile gene cassettes, often comprising antibiotic resistance genes, can be inserted or excised by a site-specific recombination mechanism (22). Several classes of integrons have been described on the basis of the sequence of the integrase gene, with class 1 integrons being the most common and widely distributed among gram-negative bacteria (13, 14, 22). The presence of type 1 and type 2 integrons has already been described in A. baumannii strains of both clinical and environmental origin (8, 11, 12, 21), with epidemic strains of A. baumannii containing significantly more integrons than nonepidemic strains (12).

An increase in the number of cases of A. baumannii has been observed over the past few years in the medical-surgical ICU of our university hospital in Italy. The objectives of the present study were (i) to investigate the molecular epidemiology of A. baumannii colonization and infection in the ICU of our university hospital, (ii) to determine whether the increase in A. baumannii acquisition from ICU patients was due to the spread of epidemic clones, (iii) to study the molecular epidemiology of A. baumannii antimicrobial resistance, and (iv) to identify clinical and therapeutic factors contributing to the selection of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii in the hospital environment.

(This study was presented in part at the 6th International Meeting on Microbial Epidemiological Markers, Les Diablerets, Switzerland, 2003. [R. Zarrilli, M. Crispino, M. Bagattini, E. Barretta, M. Triassi, and P. Villari, Abtsr. 6th IMMEM, abstr. S.7, 2003].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and study period.

The medical-surgical ICU of the 1,470-bed teaching hospital of the University “Federico II” of Naples, Naples, Italy, consists of six rooms, five two-bed rooms and one room with a maximal capacity of six patients for room. Washing sinks are available in each room, and gloves are used routinely. The bacterial isolates selected for the present study included 131 A. baumannii isolates from 131 patients from the medical-surgical ICU of University “Federico II” of Naples during two window periods from August 1999 to February 2001 and from January 2002 to December 2002.

Microbiological methods.

A. baumannii strains were collected from clinical specimens by using standard methods, isolated in pure cultures on MacConkey agar plates, and stored at −80°C with glycerol for subsequent typing. Organisms were identified by using the Vitek 2 automatic system for the identification and susceptibility testing (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). Environmental cultures (room surfaces, including walls, floor, beds and drug trolley, washing sinks, disinfectants, equipment) were obtained by swabbing all surfaces with a brain heart broth infusion moistened cotton swab (3). Culture specimens were enriched overnight at 37°C in brain heart infusion broth and then isolated in pure cultures on MacConkey agar plates. Staff hands were sampled with the direct contact method on MacConkey agar plates (3). The isolates were identified as A. baumannii spp. by using the Vitek 2 automatic system with ID-GNB card for identification of gram-negative bacilli, according to the manufacturer's instructions (bioMerieux).

Antimicrobial susceptibilities.

Antimicrobial resistance was determined by the disk diffusion method according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards document M7-A4 (18). Isolates showing an intermediate level of susceptibility were classified as resistant. Susceptibility tests were also performed by using the Vitek 2 system with AST-GN09 card according to the manufacturer's instructions (bioMerieux). The following antimicrobial agents at the indicated concentrations were tested: amikacin at 8, 16, and 64 μg/ml; ampicillin-sulbactam at 4 and 2, 16 and 8, and 32 and 16 μg/ml, respectively; aztreonam at 2, 8, and 32 μg/ml; cefazolin at 4, 16, and 64 μg/ml; cefepime at 2, 8, 16, and 32 μg/ml; cefotetan at 2, 8, and 32 μg/ml; ceftazidime at 1, 2, 8, and 32 μg/ml; ceftriaxone at 1, 2, 8, and 32 μg/ml; ciprofloxacin at 0, 5, 2, and 4 μg/ml; gentamicin at 4, 16, and 32 μg/ml; imipenem at 2, 4, and 16 μg/ml; levofloxacin at 0, 5, 4, and 8 μg/ml; meropenem at 0, 5, 4, and 16 μg/ml; piperacillin at 4, 16, and 64 μg/ml; piperacillin-tazobactam at 4 and 4, 16 and 4, and 28 and 4 μg/ml, respectively; and tobramycin at 8, 16, and 64 μg/ml. Throughout the present study, results were interpreted according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards criteria for broth microdilution and disk diffusion methods (18).

Molecular typing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and dendrogram analysis.

The preparation of genomic DNA of A. baumannii isolates was performed as previously described (29). DNA restriction was done with ApaI enzyme (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) at 25°C for 4 h. The gels were run on a CHEF-DRII system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) over 20 h at 14°C with 5 to 13 s of linear ramping at 200 V. Images of ethidium bromide-stained gels were digitized by using a Howtek Scanmaster-3 system (Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Cologno Monzese, Italy) and analyzed by using the computer software RFLPrint (PDI, Huntington Station, N.Y.). Clusters of possibly related isolates were identified by using the Dice coefficient of similarity and unweighted group method with arithmetic averages at 80%, which indicates four-to six-fragment differences in gels with an average of 20 bands (26).

DNA purification and PCR methods.

Plasmid DNA preparation was performed by using the Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) according to manufacturer's procedure. Genomic DNA preparation was performed by using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega Corp.) according to manufacturer's procedure.

PCR amplification of class 1 integron and mapping of resistance genes was performed on 0.5 μg of genomic DNA as described previously (13). Primers for the detection of class 1 integron were located in the 5′ conserved segment (5′-CS) and in the 3′-CS regions (12). Detection of class 1 and class 2 integrons by integrase gene PCR was performed according to the method of Koeleman et al. (12). Amplification of the blaIMP allele was performed with the primers 5′-ATGAGCAAGTTATCTGTATTCT-3′ (sense, positions 1 to 22, as numbered from the start of the IMP-1 gene) and 5′-TTAGTTGCTTGGTTTTGATGG-3′ (antisense, positions 721 to 741) specific for Acinetobacter IMP-1 gene (accession number AY055216). PCR conditions for IMP comprised a thermal ramp to 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 10 min at 72°C.

DNA sequencing and computer analysis of sequence data.

PCR products were purified by low-melting-point agarose gel electrophoresis, phenol-chlorophorm extraction, and ethanol precipitation. Cycle sequencing of the purified PCR products was performed by using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator v3.0 ready reaction cycle sequencing kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). DNA products were analyzed with an Applied Biosystems 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Similarity searches of the DNA sequences obtained were performed against nucleic acid sequence databases with an updated version of the BLAST program (1).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data of the class integrons from A. baumannii isolate AB-11/99 of PFGE type B and A. baumannii isolate AB-2105/02 of PFGE type I have been deposited in the GenBank nucleotide database under accession numbers AY307113, and AY307114, respectively.

Surveillance procedures.

Nosocomial infection surveillance in the medical-surgical ICU was performed by a trained physician, who reviewed the following sources for evidence of infection: physician and nurse personnel in the unit, patient charts, and diagnostic microbiological laboratory culture reports. The data collected on nosocomial infections included sites of infection, pathogens, time of acquisition from admission, and major risk factors (i.e., urinary catheterization, intravenous catheterization, and mechanical ventilation). Information about infections in the unit was recorded on a standardized form by the surveillance physician and was reviewed regularly with the attending clinician and the hospital epidemiologist. Nosocomial infections were defined by standard Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention definitions (9). Antimicrobial use rates in the ICU were calculated according to National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system report (19).

RESULTS

Molecular epidemiology of A. baumannii colonization and infection in the ICU.

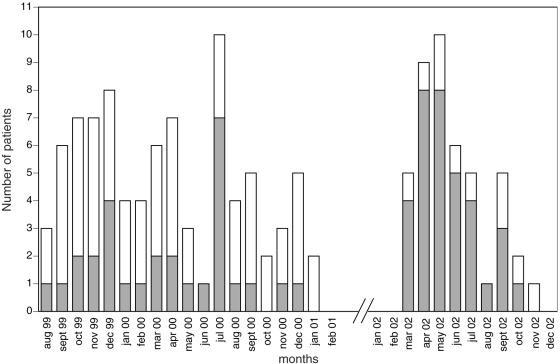

The molecular epidemiology of A. baumannii was studied in the medical-surgical ICU of University “Federico II” of Naples during two window periods, from August 1999 to February 2001 and from January 2002 to December 2002 in which an increase in the number of A. baumannii isolates was observed in the ward. Between August 1999 and February 2001, A. baumannii was isolated from 87 patients in the medical-surgical ICU, 29 of which were classified as infected and 58 of which were classified as colonized on the basis of the evaluation of the clinical chart (Fig. 1). In this study period, the four most common isolated pathogens were Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, A. baumannii, and Candida albicans, which were responsible for 24.8, 18.6, 17.9, and 13.2% of the infections, respectively. During the second window period, A. baumannii was isolated from 44 patients in the medical-surgical ICU, 34 of which were classified as infected and 10 of which were classified as colonized (Fig. 1). Between January 2002 and December 2002, A. baumannii was responsible for 34 of the 160 infections, which occurred in the unit (21.5%). Other less frequently isolated pathogens were P. aeruginosa (20.2% of all infections), S. aureus (16.9%), and C. albicans (10%).

FIG. 1.

Incidence of A. baumannii in the medical-surgical ICU of University “Federico II” of Naples. Bars: ░⃞, infected patients; □, colonized patients.

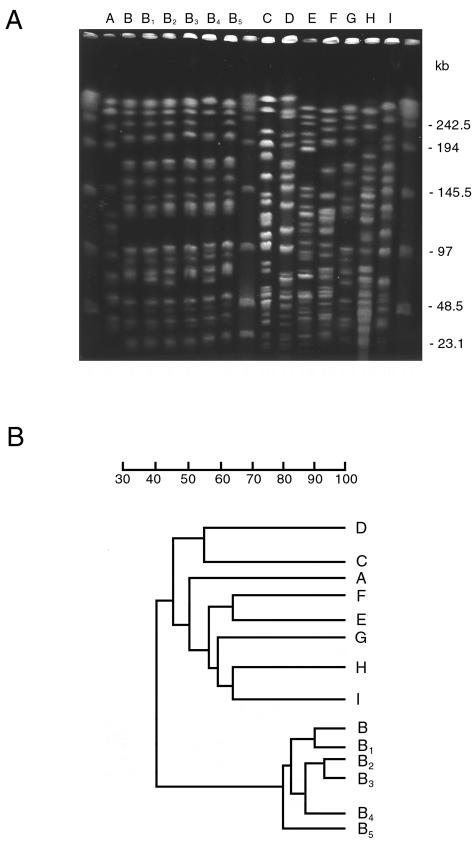

To determine whether the increase of A. baumannii isolation in ICU patients during the two window periods was due to the spread of epidemic strains, all A. baumanni isolates were genotyped by ApaI digestion, PFGE, and dendrogram analysis. Genotypic analysis of A. baumannii isolates from ICU patients identified nine major PFGE patterns, which we named from A to I, that differed in migration of at least four DNA fragments and showed a similarity of < 80% at dendrogram analysis. Of these, PFGE type B could be further classified into five subtypes, B1 to B5, that showed one-fragment to three-fragment variations in the macrorestriction pattern and a similarity of >80% upon dendrogram analysis (Fig. 2). Although seven PFGE patterns were single isolates, PFGE patterns B and I predominated, being isolated from 81 and 43 different patients, respectively. Interestingly, these two PFGE patterns occurred in two very well defined temporal clusters, with PFGE pattern B being isolated between August 1999 and January 2001 and PFGE pattern I being isolated between March and November 2002. Sporadic PFGE clones A, C, D, E, F, and G were isolated in the first window period, whereas sporadic PFGE clone H was isolated in the second window period. Multiple isolates from the same patients always showed identical PFGE patterns.

FIG. 2.

(A) PFGE profiles of A. baumannii strains isolated from different patients in ICU. Different PFGE types and subtypes identified are indicated on the top of each lane. Lateral lanes contain multimers of phage lambda DNA (48.5 kb) molecular mass markers. Sizes of lambda DNA molecular mass markers are indicated on the right of the panel. (B) Dendrogram of PFGE macro restriction patterns generated with the RFLPrint computer software. The scale indicates percent similarity.

Features of clinical isolates from patients in the ICU colonized or infected with different A. baumannii PFGE clones are shown in Table 1. PFGE clone B was responsible for 52 colonizations and 29 infections, whereas PFGE clone I was responsible for 9 colonizations and 34 infections. The lower respiratory tract was the most frequent site of isolation (70 of 81 and 36 of 43, respectively) and was associated with clinical infection in 18 of 70 and 27 of 36 patients for PFGE clones B and I, respectively. PFGE clones B and I were also isolated from the urinary tract of four and two patients or from the blood of six and five patients, respectively, and were always associated with clinical infection. PFGE clone B was also isolated once from an infected surgical wound. Sporadic PFGE clones A, C, D, E, F, G, and H all colonized the upper respiratory tract.

TABLE 1.

Features of clinical isolates from patients in the ICU colonized or infected with different A. baumannii PFGE clonesa

| PFGE clone | No. of isolates from: |

Total no. of isolates |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| URT |

LRT |

UT |

Blood |

Wound |

||||||||

| C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | |

| A | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| B | 52 | 18 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 52 | 29 | |||||

| C | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| D | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| E | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| F | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| G | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| H | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| I | 9 | 27 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 34 | ||||||

Abbreviations: URT, upper respiratory tract; LRT, lower respiratory tract; UT, urinary tract; C, colonized patients; I, infected patients.

Extensive environmental investigations were performed during the second study period to identify sources and reservoirs of infection. Samples were obtained from various sites of the ICU, including room surfaces (6), bed frames (6), sinks (4), monitors (6), humidifiers (6), and staff hands (4). A. baumannii was isolated from three monitors and three humidifiers of three different beds located in two different rooms and from the hands of two nurses. All A. baumannii environmental isolates showed the identical PFGE pattern I.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of A. baumannii isolates.

It has been previously shown that A. baumannii infections can be selected because of the broad antibiotic resistance exhibited by this organism (3-7, 10, 15, 16, 24, 25, 28). We therefore evaluated whether the spread of the two A. baumannii epidemic PFGE clones B and I in the ICU would have been sustained by a particular multidrug-resistant phenotype. To address this issue, we analyzed the antibiotype of different A. baumannii strains isolated in the ward. As shown in Table 2, A. baumannii strains with different PFGE profiles all exhibited a multiply resistant antibiotype characterized by resistance to monobactams and ceftriaxone and resistance or intermediate susceptibility to ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, broad-spectrum cephems, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides. On the contrary, eight of nine A. baumannii PFGE types were susceptible to carbapenems. A. baumannii epidemic strains of PFGE type B were resistant to the majority of antimicrobials, including ampicillin-sulbactam, but sensitive to cefepime, carbapenems, netilmicin, and tobramycin. A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I showed a particular multidrug-resistant antibiotype characterized by resistance to the majority of antimicrobials tested, including carbapenems, and susceptibility to ampicillin-sulbactam and gentamicin. All A. baumannii strains of identical PFGE profile showed the same antibiotype (data not shown). Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I were also analyzed by using a broth microdilution method. These experiments showed that A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I were susceptible to ampicillin-sulbactam (MIC, 8 mg/liter) and gentamicin (MIC, 4 mg/liter) and of intermediate resistance to tobramycin (MIC, 8 mg/liter), imipenem (MIC, 8 mg/liter), and meropenem (MIC, 8 mg/liter) but resistant to all other antimicrobials (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of A. baumannii PFGE clones in the ICU

| Antimicrobial agent | Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of PFGE clone: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | s | r | s | r | s | r | r | s | s |

| Piperacillin | r | r | s | r | r | r | s | r | r |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | s | r | r | r | r | s | s | s | r |

| Cefepime | s | s | r | r | r | s | s | r | r |

| Ceftazidime | s | r | s | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| Ceftriaxone | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| Aztreonam | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| Imipenem | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | r |

| Meropenem | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | r |

| Amikacin | s | r | s | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| Gentamicin | s | r | r | r | r | r | r | s | s |

| Netilmicin | s | s | s | s | r | s | s | r | r |

| Tobramycin | s | s | s | s | r | r | r | r | r |

| Ciprofloxacin | s | r | s | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| Levofloxacin | s | r | s | r | r | r | r | r | r |

Abbreviations: s, Susceptible; r, resistant. Antimicrobial resistance was determined by the disk diffusion method. Isolates showing an intermediate level of susceptibility were classified as resistant.

Characterization of class 1 integrons in epidemic A. baumannii strains.

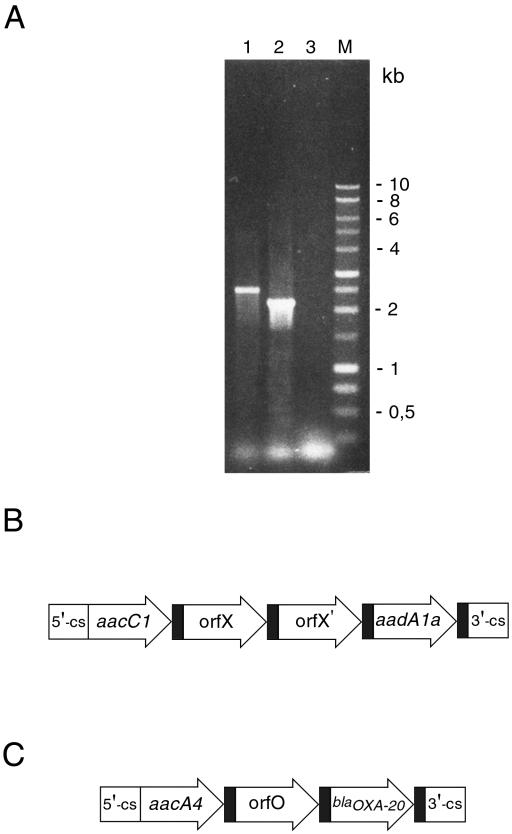

To further investigate the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii strains, we sought to determine whether antibiotic resistance genes might be located in mobile gene cassettes. To address this issue, A. baumannii isolates were analyzed for integron content and sequences of the amplification product. The variable regions of type 1 integrons were amplified with the primers 5′CS and 3′CS, which annealed with the DNA regions flanking the recombination site attI (13). Single amplification products of approximately 2.5 and 2.2 kb were obtained from chromosomal DNA of all A. baumannii strains of identical PFGE types B and I, respectively (Fig. 3 and data not shown). Also, an amplicon of 2.5 kb was detected in all A. baumannii strains of different PFGE B subtypes. No amplification products were obtained from sporadic PFGE clones A, C, D, E, F, G, and H (data not shown). Nucleotide analysis of integron from A. baumannii strains of PFGE type B showed an amplicon of 2,542 bp containing four gene cassettes: aacC1, encoding an AAC (3)-Ia aminoglycoside acetyltransferase, which confers resistance to gentamicin; two open reading frames coding for unknown products; and aadA1a gene, which encodes an AAD(3")-Ia aminoglycoside adenyltransferase that confers resistance to spectinomycin and streptomycin. Sequence analysis of integron from A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I showed an amplicon of 2,230 bp containing three gene cassettes: an aacA4 allele encoding an AAC(6′)-Ib aminoglycoside acetyltransferase that confers resistance to amikacin, netilmicin, and tobramycin; an open reading frame coding for an as-yet-undetermined product; and blaOXA-20, a gene coding for a class D β-lactamase that confers resistance to amoxicillin, ticarcillin, oxacillin, and cloxacillin (17). The presence of integrons in A. baumannii strains was also evaluated by integrase gene PCR to detect intI1 and intI2 genes (12). Class 1 integrons were detected in all A. baumannii strains of PFGE type B and I, but in none of PFGE clones A, C, D, E, F, G, and H. On the other hand, class 2 integrons were not found in any of A. baumannii strains (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

(A) PCR amplification, with the 5′-CS and 3′-CS primers, of variable regions of integrons from A. baumannii epidemic PFGE clones B and I. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.0% agarose. Lane 1, genomic DNA from A. baumannii epidemic PFGE clones B; lane 2, genomic DNA from A. baumannii epidemic PFGE clones I; lane 3, negative control (no DNA); lane M, 1-kb DNA ladder. Sizes in base pairs (bp) of 1-kb DNA ladder molecular mass markers are indicated on the right of the panel. (B) Structure of the variable region of type 1 integron amplified in A. baumannii epidemic PFGE clones B. (C) Structure of the variable region of type 1 integron amplified in A. baumannii epidemic PFGE clones I. Coding sequences are indicated by arrows with the corresponding names; the attC sites are indicated by black filled rectangles.

Molecular analysis of carbapenem resistance of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I.

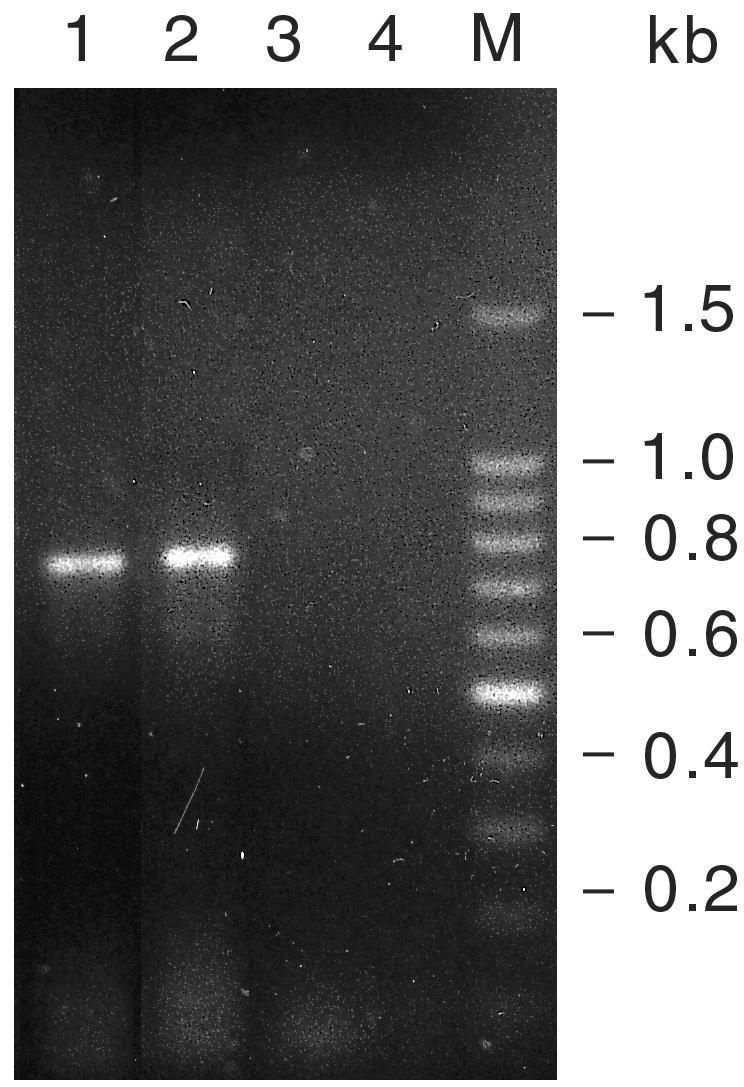

To characterize the resistance to carbapenems of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I, PCR analysis was performed on chromosomal DNA with primers specific for either IMP- or VIM type class B carbapenemase genes. As shown in Fig. 4, the blaIMP allele compatible with the expected size of 741 bp was amplified from chromosomal DNA of all A. baumannii strains of identical PFGE type I but not from those of PFGE type B (Fig. 4 and data not shown). On the other hand, no VIM-type class B carbapenemase genes were amplified by PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA from A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

PCR amplification of blaIMP allele from A. baumannii epidemic PFGE clones I. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.2% agarose. Lanes 1 and 2, genomic DNA from A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I; lane 3, genomic DNA from A. baumannii strain of PFGE type B; lane 4, negative control (no DNA); lane M, 100-bp DNA ladder. Sizes in base pairs of 100-bp DNA ladder molecular mass markers are indicated on the right of the panel.

Antimicrobial use rates in the ICU.

To identify clinical and therapeutic factors contributing to the selection of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii epidemic clones in the hospital environment, we analyzed the use of selected antimicrobial agents in the ICU from January 1999 to December 2002. As shown in Table 3, use rates of antimicrobials of the ampicillin group were close to the 50th percentile of use rates reported by the NNIS for medical-surgical ICU (19) and increased to the 75th percentile during year 2002. Use rates of antipseudomonal penicillins during the entire study period were close to the 50th percentile of use rates reported by the NNIS (19). Use rates of broad-spectrum cephalosporins in 1999, 2000, and 2002 were close to the 50th percentile of the use rates reported by the NNIS (19) but increased to the 90th percentile in 2001. Use rates of carbapenems, although decreasing in 2001 and 2002, were always higher than the 90th percentile of the NNIS data (19). Use rates of fluoroquinolones increased from the 50th percentile in 1999 and 2000 to the 75th percentile in 2001 and 2002. On the other hand, use rates of aminoglycosides, although elevated, decreased from 182 to 73.2 defined daily doses/1,000 patient-days during years 1999 and 2002, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Antimicrobial use rates in the ICU during the study perioda

| Antimicrobial agent groupa | DDDb rate in: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| Ampicillin group | 78.6 | 62.6 | 87.3 | 133.28 |

| Antipseudomonal penicillins | 67 | 86.4 | 72.5 | 85.92 |

| Broad-spectrum cephalosporins | 195 | 226.7 | 330.2 | 220.6 |

| Carbapenem group | 231 | 218.1 | 175.85 | 154.37 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 85 | 75.6 | 163.58 | 149.55 |

| Aminoglycosides | 182 | 112.3 | 84.7 | 73.2 |

The antimicrobials utilized in the ICU were divided by class and group according to an NNIS system report (19). The ampicillin group included ampicillin, ampicillin-sulbactam, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; the antipseudomonal penicillins included piperacillin-tazobactam and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid; the broad- spectrum cephalosporins included cefotaxime, cefotetan, ceftazidime, and ceftriaxone; the carbapenem group included imipenem and meropenem; the fluoroquinolones included ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin; and the aminoglycosides included amikacin, netilmicin, tobramycin, and gentamicin.

The DDD of an antimicrobial agent was calculated by dividing the total grams of the antimicrobial agent used in the ward by the number of grams in an average daily dose of the agent given to an adult patient. DDD rates were calculated by dividing the DDD of the specific agent used for the total number of patient-days × 1,000.

DISCUSSION

Multidrug-resistant A. baumannii has increasingly been recognized as being responsible for large and sustained hospital outbreaks, particularly in ICU wards (4, 6, 7, 10, 15, 16, 24, 29). Invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures used in hospital ICUs have been demonstrated to predispose subjects to severe infections with A. baumannii (4, 6, 15, 24, 29). In our institution, A. baumannii nosocomial infections were circumscribed to the sole ICU ward (29). The data presented here show that nosocomial infections and colonizations by A. baumannii in the ICU were prolonged for several months, the first epidemic lasting 18 months and the second epidemic lasting 9 months. The impact of A. baumannii on ICU-acquired infections was substantial and differed in the two study periods, with A. baumannii being the third most prevalent cause of infection from August 1999 to February 2001 and the first most prevalent cause of infection from January 2002 to December 2002. Thus, at least during the two window periods, A. baumannii epidemic infections became endemic in the ICU.

Molecular typing of A. baumannii isolates showed that the two sequential outbreaks were caused by the spread of two different epidemic clones, which coexisted with unrelated sporadic different strains. The first epidemic clone showed an unstable PFGE pattern with the presence of several subtypes during the 18 months of isolation. On the other hand, the second outbreak episode was caused by the spread of a single different epidemic clone. This is in agreement with our previous data showing that sequential A. baumannii epidemics in the same ICU were caused by different clones, one replacing the other in a well-defined temporal order (29). Contaminated environmental sources, including humidifiers and monitors, and hand carriage by patient-care personnel were identified during the second A. baumannii outbreak, suggesting the horizontal transmission of the epidemic strains from one patient to another through the hospital staff. Because multivariate analysis has previously identified mechanical ventilation as a major risk factor for A. baumannii acquisition in the same ICU ward (29), we postulate that any maneuver associated with mechanical ventilation might have been the mode of A. baumannii patient-to-patient transmission during the two sequential outbreaks described in the present study. In partial support of this hypothesis, the respiratory tract was the most frequent site of isolation for both sporadic and epidemic clones, with the latter being isolated only from the lower respiratory tract. Our data also demonstrated that the two epidemic A. baumannii clones resulted in a worse clinical outcome compared to sporadic clones; the epidemic clone of the B genotype was responsible for 29 infections, and the epidemic clone of the I genotype was responsible for 34 infections, whereas the sporadic clones resulted only in colonizations.

Several studies indicate that A. baumannii strains responsible for nosocomial infections have been selected because of their highly resistant phenotype (3-7, 10, 15, 16, 24, 25, 28). In particular, the emergence and spread of resistance to amikacin (8, 28) or carbapenems (3, 6, 10, 16, 25) have been reported during hospital outbreaks of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii. Accordingly, the analysis of the antibiotype of A. baumannii clones isolated in the present study showed that the two sequential epidemic clones and three of the seven sporadic strains were highly resistant. In particular, the A. baumannii epidemic clone of the B genotype was resistant to ampicillin-sulbactam, broad-spectrum cephalosporins, gentamicin, and amikacin but sensitive to carbapenems. On the other hand, A. baumannii epidemic genotype I clone was resistant to the majority of antimicrobials tested, including carbapenems and most aminoglycosides, but sensitive to ampicillin-sulbactam and gentamicin. The simultaneous occurrence of resistance to amikacin and carbapenems in A. baumannii epidemic genotype I clone might have been responsible for the high rate of infection during the second A. baumannii outbreak in our ICU. It has been recently demonstrated that the major selection pressure driving changes in the frequency of antibiotic resistance is the volume of drug use (2). The use of antibiotics can contribute to the persistence and spread of the outbreaks caused by multidrug-resistant A. baumannii (3, 5-8, 10, 15, 16, 25, 28). Our data show elevated use rates of broad-spectrum cephalosporins, carbapenems, and aminoglycosides in the ICU from 1999 to 2002. This may have selected the two sequential epidemics caused by multidrug-resistant A. baumannii, particularly strains resistant to antibiotics highly used in the ICU. In accordance with this, it has been shown that the risk of A. baumannii acquisition increases in case of use of broad-spectrum cephalosporins and aminoglycosides (29). Also, prior aminoglycoside therapy has been identified as risk factor for multidrug-resistant A. baumannii bloodstream infections (24).

Additional epidemiological information was provided by the molecular typing of A. baumannii antimicrobial resistance. Type 1 integrons were amplified from the genomic DNA of the two A. baumannii epidemic clones but not from the genomic DNA of sporadic clones. This is in agreement with previous data showing that integron-located antimicrobial resistance genes are frequently found in epidemic strains of A. baumannii (12). PCR and sequence analysis of antimicrobial resistance genes located in mobile DNA elements demonstrated the presence of integron-located aacC1 and aadA1a resistance genes in A. baumannii strains of PFGE type B, a finding consistent with their phenotypic resistance to gentamicin. On the other hand, integron isolated in A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I contained an aacA4 allele that confers resistance to amikacin, netilmicin, and tobramycin and blaOXA-20, a gene coding for a class D β-lactamase, which confers resistance to amoxicillin, ticarcillin, oxacillin, and cloxacillin (17). The presence of aacA4 resistance gene correlates well with the resistance of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I to all aminoglycosides, with the exception of gentamicin. A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I were also characterized by intermediate resistance to carbapenems, with imipenem and meropenem having MICs of 8 mg/liter. Our data showed that blaIMP allele was amplified from chromosomal DNA of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I. This is consistent with several reports showing that allelic variants of IMP-type β-lactamase are responsible for carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter spp. (5, 23, 27). Also, in keeping with our data, Acinetobacter clinical isolates carrying blaIMP-1 or blaIMP-4 alleles exhibit different levels of carbapenem resistance, with MICs varying from 4 to 32 mg/liter (5, 27).

Antimicrobial resistance in A. baumannii strains might have been acquired either through horizontal gene transfer or selection of novel resistant clones. The data reported here show that the same cassette arrays are found in all integrons isolated in A. baumannii strains of PFGE types B and I, suggesting that antimicrobial resistances have been acquired through selection of two independent resistant clones. This finding is in agreement with previous data showing that the spread of both amikacin (8, 28) and carbapenem (6) resistances in A. baumannii strains isolated from different hospitals in Spain was due to the acquisition of two new epidemic strains. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that antimicrobial resistances might have been acquired through horizontal gene transfer. In partial support of this hypothesis, the same cassette array of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type B was found also in type 1 integrons of several clinical isolates from Italian hospitals belonging to different ribotype groups (11). Also, the same cassette array of integron of A. baumannii strains of PFGE type I was found in type 1 integrons of A. baumannii isolates from Italy (11), France (21), and Spain (20). In the latter case, however, the gene, designated blaOXA-37, differs from the OXA-20 gene in 2 bp, with one of the mutations being silent and the other generating a substitution of glutamic acid for aspartic acid (20). Moreover, the presence of integrons containing the same organization of cassettes in A. baumannii strains with different genotypes further suggests a horizontal gene transfer of integrons (11, 21).

In conclusion, we show here that A. baumannii strains cause large and sustained hospital outbreaks and identify factors involved in the emergence and spread of their antimicrobial resistances. The two epidemics were due to the dissemination of two distinct clones that were selected because of the presence of aminoglycoside and beta-lactam resistance gene cassettes within class 1 integrons, as well as a chromosomal blaIMP allele, and the high use rates of broad-spectrum cephalosporins, carbapenems, and aminoglycosides in the ward. The incidence and spread of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii nosocomial infections suggest the necessity of a surveillance program to prevent colonization and infection by multidrug-resistant bacteria and antimicrobial resistance selection and dissemination. This program would require monitoring ICU-acquired infections and antibiotic use, as well as molecular typing of bacterial isolates and characterization of antibiotic resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ornella Piazza for assistance in the evaluation of patients' charts and all of the Biomedical Scientists working in the Microbiology Section of our Hospital who saved isolates from clinical samples for the study. We also thank Domenico Vitale from CEINGE, Napoli, Italy, for technical support in DNA sequencing; Geremia Fusco for technical assistance; and M. Berardone for the artwork.

This study was supported in part by grants from the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica, and the Ministero della Sanità of Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin, D. J., K. G. Kristinsson, and R. M. Anderson. 1999. The relationship between the volume of antimicrobial consumption in human communities and the frequency of resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1152-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aygun, G., O. Demirkiran, T. Utku, B. Mete, S. Urkmez, M. Yilmaz, H. Yasar, Y. Dikmen, and R. Ozturk. 2002. Environmental contamination during a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak in an intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 52:259-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergogne-Berezin, E., and K. J. Towner. 1996. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:148-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu, Y. W., M. Afzal-Shah, E. T. Houang, M. I. Palepou, D. J. Lyon, N. Woodford, N., and D. M. Livermore. 2001. IMP-4, a novel metallo-beta-lactamase from nosocomial Acinetobacter spp. collected in Hong Kong between 1994 and 1998. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:710-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbella, X., A. Montero, M. Pujol, M. A. Dominguez, J. Ayats, M. J. Argerich, F. Garrigosa, J. Ariza, and F. Gudiol. 2000. Emergence and rapid spread of carbapenem resistance during a large and sustained hospital outbreak of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4086-4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gales, A. C., R. N. Jones, K. R. Forward, J. Linares, H. S. Sader, and J. Verhoef. 2001. Emerging importance of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter species and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia as pathogens in seriously ill patients: geographic patterns, epidemiological features, and trends in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997-1999). Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 2):S104-S113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallego, L., and K. J. Towner. 2001. Carriage of class 1 integrons and antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from Northern Spain. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaynes, R. P., and T. C. Horan. 1996. Surveillance of nosocomial infections, p. 1017-1031. In C. G. Mayall (ed.), Hospital epidemiology and infection control. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 10.Go, E. S., C. Urban, J. Burns, B. Kreiswirth, W. Eisner, N. Mariano, K. Mosinka-Snipas, and J. J. Rahal. 1994. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of Acinetobacter infections sensitive only to polymyxin B and sulbactam. Lancet 344:1329-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gombac, F., M. L. Riccio, G. M. Rossolini, C. Lagatolla, E. Tonin, C. Monti-Bragadin, A. Lavenia, and L. Dolzani. 2002. Molecular characterization of integrons in epidemiologically unrelated clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from Italian hospitals reveals a limited diversity of gene cassette arrays. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3665-3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koeleman, J. G., J. Stoof, J., M. W. van der Bijl, C. M. J. E. Vanderbroucke-Grauls, and P. H. M. Savelkou. 2001. Identification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumanni by integrase gene PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levesque, C., L. Piché, C. Larose, and P. H. Roy. 1995. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maguire, A. J., D. F. Brown, J. J. Gray, and U. Desselberger. 2001. Rapid screening technique for class 1 integrons in Enterobacteriaceae and nonfermenting gram-negative bacteria and its use in molecular epidemiology. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1022-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahgoub, S., J. Ahmed, and A. E. Glatt. 2002. Underlying characteristics of patients harboring highly resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Am. J. Infect. Control 30:386-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manikal, V. M., D. Landman, G. Saurina, E. Oydna, H. Lal, and J. Quale. 2000. Endemic carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter species in Brooklyn, New York: citywide prevalence, interinstitutional spread, and relation to antibiotic usage. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naas, T., W. Sougakoff, A. Casetta, and P. Nordmann. 1998. Molecular characterization of OXA-20, a novel class D beta-lactamase, and its integron from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2074-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard. NCCLS document M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 19.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. 2002. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System report: data summary from January 1992 to June 2002. Am. J. Infect. Control 30:458-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navia, M. M., J. Ruiz, and J. Vila. 2002. Characterization of an integron carrying a new class D beta-lactamase (OXA-37) in Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ploy, M.-C., F. Denis, P. Courvalin, and T. Lambert. 2000. Molecular chracterization of integrons in Acinetobacter baumannii: description of a hybrid class 2 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2684-2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Recchia G. D., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology 141:3015-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smolyakov, R., A. Borera, K. Riesenberga, F. Schlaeffera, M. Alkana, A. Porathb, D. Rimarb, Y. Almogc, and J. Gilad. 2003. Nosocomial multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bloodstream infection: risk factors and outcome with ampicillin-sulbactam treatment. J. Hosp. Infect. 54:32-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi, A, S. Yomoda, I. Kobayashi, T. Okubo, M. Tsunoda, and S. Iyobe. 2000. Detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in a hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:526-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tysall, L., Stockdale, M. W., Chadwick, P. R., Palepou, M. F., Towner, K. J., Livermore, D. M., and Woodford, N. 2002. IMP-1 carbapenemase detected in an Acinetobacter clinical isolate from the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:217-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, M. Navia, B. Becerril, I. Garcia, S. Perea, I. Lopez-Hernandez, I. Alamo, F. Ballester, A. M. Planes, J. Martinez-Beltran, and T. J. de Anta. 1999. Spread of amikacin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated in Spain due to an epidemic strain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:758-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villari, P., L. Iacuzio, E. A. Vozzella, and U. Bosco. 1999. Unusual genetic heterogeneity of Acinetobacter baumanni isolates in a university hospital in Italy. Am. J. Infect. Control 27:247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]