Abstract

We report the successful resection of a solitary, apparently primary, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the heart, in a 70-year-old man who had presented with progressive dyspnea. The tumor occupied the right atrium and almost completely obstructed the superior and inferior venae cavae; it also involved the aortic root and the interatrial septum. To postpone the patient's impending cardiac failure, we resected the gross tumor except in the region of the aortic root and the trigone, which we debulked. We completely reconstructed the right atrium with pericardium and the interatrial septum with a pericardial patch. The patient recovered uneventfully; 18 months postoperatively, he had experienced only local recurrence in the tumor bed. This case shows that the palliative resection of large neuroendocrine tumors of the heart can yield good outcomes and prolong patient survival. To our knowledge, ours is the only report of a high-grade neuroendocrine cardiac tumor of apparently primary origin to have been resected with good palliative results.

Key words: Carcinoma, neuroendocrine/surgery; diagnosis, differential; heart neoplasms/diagnosis/epidemiology/pathology/surgery; neuroendocrine tumors/diagnosis; treatment outcome

Cardiac tumors can be either primary or metastatic. Primary tumors of the heart are rare, with an incidence of 0.0017% to 0.19% in unselected autopsy series.1 Tumors that metastasize to the heart are much more common, with an incidence as high as 12% in all autopsies of patients with a malignancy. Most such metastatic tumors are melanomas, breast carcinomas, lymphomas, leukemia, and sarcomas.2 Neuroendocrine tumors of the heart are reportedly very rare—most have metastasized from gastrointestinal or pulmonary tumors, and a minuscule percentage have been solitary cardiac neuroendocrine tumors. Treatment is usually palliative, because patients rarely have solitary disease that is amenable to resection.1–3

We describe the case of a patient who underwent the palliative resection of a high-grade solitary neuroendocrine cardiac tumor.

Case Report

In October 2008, a 70-year-old man presented with progressive shortness of breath. A chest radiograph showed cardiomegaly. A computed tomogram (CT) of the chest showed a large mass that occupied the entire right atrium and caused a moderate pericardial effusion. The patient's medical history included the excision of several squamous cell carcinomas from his face 7 or 8 years previously. He subsequently developed an enlarged lymph node in the left side of his neck. This entity was a poorly differentiated carcinoma with basaloid features. The patient underwent tonsillectomy, neck lymph node dissection, and radiation therapy 6 years before the current presentation. His medical history also included prostate carcinoma, which had been treated with 75 Gy of radiation in 2002.

Surgical removal of the current cardiac mass was scheduled. Median sternotomy was performed, but the mass was found to involve the superior vena cava (SVC), the aortic root, and both atria. The procedure was aborted and only a biopsy was performed. Histologic examination revealed a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma with characteristics different from those of the patient's prior carcinomas. After recovering from the sternotomy, the patient was treated with 6 cycles of cisplatin and etoposide. He then underwent complete axial and metabolic imaging (magnetic resonance, CT, and positron emission tomography/CT). This revealed tumor progression with involvement of the aortic root and obstruction of both venae cavae.

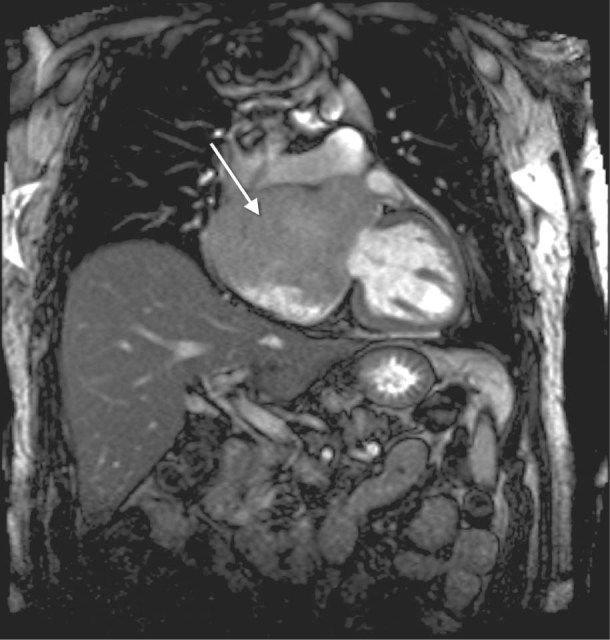

The patient was referred to the MD Anderson Cancer Center. Chest CT and cardiac magnetic resonance showed an 8.4 × 10 × 10.6-cm malignant tumor in the right and left atria, with extension into and obstruction of the SVC (Figs. 1 and 2). Left- and right-side heart catheterization revealed normal left ventricular function, normal right-side heart pressures, mild-to-moderate coronary artery disease, and a left atrial mass.

Fig. 1 Magnetic resonance image shows a large right atrial mass (arrow) extending to the aortic root.

Fig. 2 Chest computed tomogram shows a large right atrial mass (arrow).

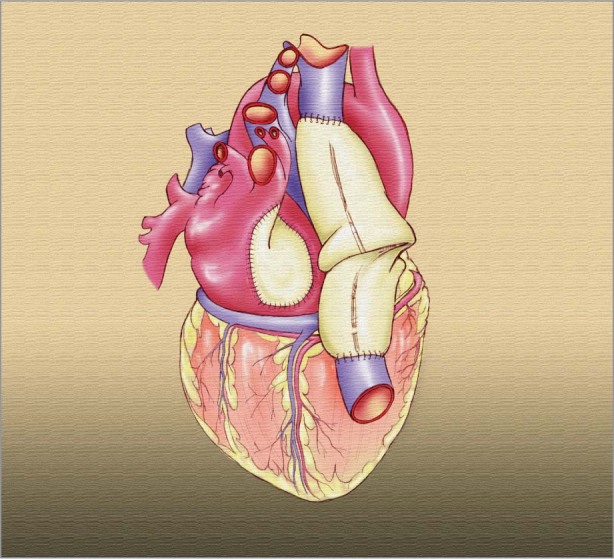

The patient did not respond to chemotherapy, had a large cardiac mass with no evidence of other disease, and was fairly functional, so palliative resection was offered to postpone impending cardiac failure and prolong his survival. In July 2009, through a median sternotomy and with use of cardiopulmonary bypass, we made an incision in the right atrium from the SVC to the inferior vena cava, which enabled a direct view of the cardiac tumor. Neither the coronary sinus nor the tricuspid valve was involved; however, medially the tumor completely involved the aortic root and interatrial septum. Neither an R0 resection (complete tumor resection with negative microscopic margins) nor an R1 resection (resection with positive microscopic margins) was feasible. Our approach was to resect the gross tumor but only to debulk the region of the aortic root and the trigone. We completely reconstructed the right atrium by means of an end-to-side anastomosis of pericardial caval tube-graft to the tricuspid ring. The interatrial septum was reconstructed with use of a pericardial patch (Fig. 3). The patient was weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass, his chest was closed, and he was taken to the cardiac intensive care unit in stable condition.

Fig. 3 Artist's drawing depicts the right atrium after its reconstruction with pericardium.

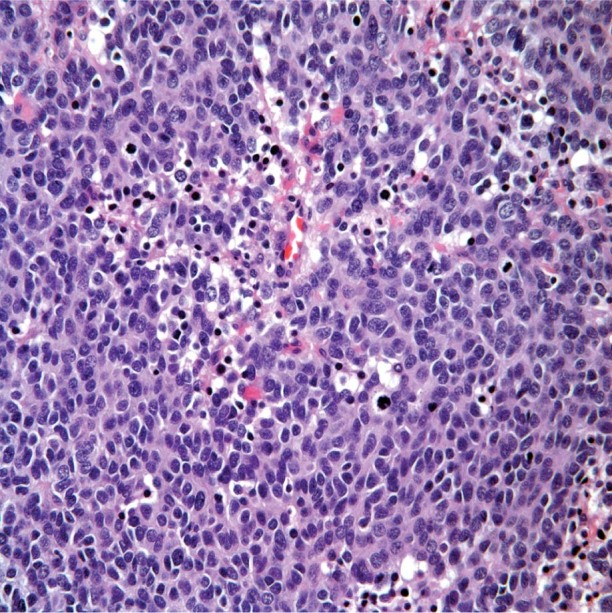

Pathologic studies revealed a solid, irregularly shaped, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, white to yellow-tan in color and 11.5 × 8 × 5 cm in size (Fig. 4). Histologically, the tumor was composed of reactive small cells that had scanty cytoplasm. Results of immunohistochemical analysis revealed diffuse strong positivity for anti-cytokeratin (CK) (AE1/AE3), CK20, synaptophysin, and vimentin, and negative staining for CK7, prostate-specific antigen, melanoma markers, leukocyte common antigen, and chromogranin. On the basis of the histologic features of the tumor and the immunohistochemical pattern, the site of origin could not be determined and the tumor was thought to be primary (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 Photograph shows the gross tumor after excision.

Fig. 5 Photomicrograph shows poorly differentiated small cells with scanty cytoplasm, characteristic of a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (H & E, orig. ×40).

The patient needed a permanent pacemaker but otherwise recovered uneventfully. He underwent regular follow-up examinations and adjuvant radiotherapy. He remained asymptomatic; however, CT of the chest 18 months postoperatively revealed local recurrence in the tumor bed. The patient underwent palliative chemotherapy beginning in March 2011, and died of his disease in September 2012.

Discussion

To our knowledge, ours is the only report of a high-grade neuroendocrine cardiac tumor of apparently primary origin to be resected with good palliative results.

Cardiac neuroendocrine carcinomas are extremely rare and are usually metastatic. Most of these neoplasms spread to other sites, including lymph nodes and the liver. The most common primary sites are the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and mediastinum; infrequently, a Merkel cell (skin) carcinoma is the origin.3–6 It is uncommon for a cardiac neuroendocrine carcinoma to present as a solitary tumor without diffuse metastatic disease. In 3 previous case reports describing solitary cardiac neuroendocrine tumors,7–9 all of the tumors had a gastrointestinal source but no liver metastasis. The presence of a neuroendocrine carcinoma in the heart of a patient with no history of ileal carcinoid tumor, pulmonary neuroendocrine tumor, Merkel cell carcinoma, or liver metastasis is, to our knowledge, clinically unique. Our patient had a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that was positive for CK20 and negative for CK7, without evidence of gastrointestinal or lung carcinoma in the imaging or his medical history. Cytokeratins help to differentiate the origin of malignancies; however, their sensitivity and specificity is far below 100%. Tumors of gastrointestinal origin and from skin malignancies such as Merkel cell carcinoma can contain CK20; CK7 is present in lung, ovarian, and salivary tumors. Cardiac neuroendocrine carcinomas have not been well characterized on the basis of CK positivity. Synaptophysin is an immunohistochemical marker in neuroendocrine tumors, so the positivity of this marker in our patient confirms that his was a neuroendocrine neoplasm.10 Our patient had no evidence of metastatic disease and no history of Merkel cell carcinoma, lung carcinoma, or gastrointestinal carcinoid, and (after 18 months of follow-up) no manifestation of disease apart from local recurrence. Therefore, it is highly likely that his neoplasm was a primary cardiac high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma. The tumor also could have been a solitary myocardial metastatic neuroendocrine tumor of unknown primary origin; however, such would be clinically uncommon, and the primary source would have become evident after follow-up investigation. In reported series of high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of unknown primary origin, most patients had multiple sites of metastasis.11,12

We found no randomized trials that describe the treatment of high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the heart. Treatment for this type of tumor usually consists of surgical resection and platinum-based chemotherapy.13,14 High-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas are aggressive. In a case series of tumors with similar histologic characteristics, the mean survival time was 13 months.15 Complete resection is the treatment of choice; however, major involvement of the cardiac chambers can preclude complete and clear surgical margins. Our case shows that, although the diagnosis and treatment of high-grade cardiac neuroendocrine carcinomas can be complex and challenging, it is possible to achieve good outcomes with palliative resection.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Michael J. Reardon, MD, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center, 6550 Fannin St., Suite 1401, Houston, TX 77030

E-mail: mreardon@tmhs.org

References

- 1.Bakaeen FG, Reardon MJ, Coselli JS, Miller CC, Howell JF, Lawrie GM, et al. Surgical outcome in 85 patients with primary cardiac tumors. Am J Surg 2003;186(6):641–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Abraham KP, Reddy V, Gattuso P. Neoplasms metastatic to the heart: review of 3314 consecutive autopsies. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol 1990;3(3):195–8. [PubMed]

- 3.Jann H, Wertenbruch T, Pape U, Ozcelik C, Denecke T, Mehl S, et al. A matter of the heart: myocardial metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Horm Metab Res 2010;42(13):967–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Pasieka JL, Schnell G, Abdel-Aty H, Rorstad O. Metastatic midgut carcinoid to the heart demonstrated on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Clin Oncol 2009;32(3):328–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Minicucci MF, Zornoff LA, Okoshi MP, Bueno SP, Matsubara BB, Azevedo PS, et al. Heart failure due to right ventricular metastatic neuroendocrine tumor. Int J Cardiol 2008; 126(2):e25–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Drake WM, Jenkins PJ, Phillips RR, Lowe DG, Grossman AB, Besser GM, Wass JA. Intracardiac metastases from neuroendocrine tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1997;46(4): 517–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Fine SN, Gaynor ML, Isom OW, Dannenberg AJ. Carcinoid tumor metastatic to the heart. Am J Med 1990;89(5):690–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kasi VS, Ahsanuddin AN, Gilbert C, Orr L, Moran J, Sorrell VL. Isolated metastatic myocardial carcinoid tumor in a 48-year-old man. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77(6):591–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Patel CN, Anthoney A, Treanor D, Scarsbrook AF. Solitary myocardial metastasis from small-bowel neuroendocrine carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(10):1724–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Chu P, Wu E, Weiss LM. Cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 expression in epithelial neoplasms: a survey of 435 cases. Mod Pathol 2000;13(9):962–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hainsworth JD, Spigel DR, Litchy S, Greco FA. Phase II trial of paclitaxel, carboplatin, and etoposide in advanced poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma: a Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network Study. J Clin Oncol 2006;24(22): 3548–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Greco FA, Hainsworth JD. Cancer of unknown primary site. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenburg SA, editors. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenburg's cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. p. 2363–87.

- 13.Strosberg JR, Coppola D, Klimstra DS, Phan AT, Kulke MH, Wiseman GA, et al. The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of poorly differentiated (high-grade) extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Pancreas 2010;39(6):799–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mitry E, Baudin E, Ducreux M, Sabourin JC, Rufie P, Aparicio T, et al. Treatment of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumours with etoposide and cisplatin. Br J Cancer 1999;81 (8):1351–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Brenner B, Shia J, Klimstra DS, Gonen M, Shah A, Leonard GD, Kelsen DP. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience of 143 cases [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2004 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post-Meeting Edition) 2004;22(14S):4123.