Abstract

T2* quantification has been shown to noninvasively and accurately estimate tissue iron content in the liver and heart; applying this to thin-walled carotid arteries introduces a new challenge to the estimation process. With most imaging voxels in a vessel being along its boundaries, errors in parameter estimation may result from partial volume mixing and misregistration due to motion in addition to noise and other common error sources. To minimize these errors, we propose a novel technique to reliably estimate T2* in thin regions of vessel wall. The technique weights data points to reduce the influence of expected error sources. It uses neighborhoods of data to increase the number of points for fitting and to assess lack of fit for automated outlier detection and deletion. The performance of this method was observed in simulations, phantom and in vivo patient studies and compared to results obtained using a pixelwise linear least squares estimation of T2*. The new proposed method showed a closer match to the expected results, and a 4.2-fold decrease in interobserver variability for in vivo studies. This increased confidence in estimation should improve the ability to reliably quantify iron noninvasively in the arterial wall.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Iron, T2*, Atherosclerosis

1. Background

Atherosclerosis is the major underlying cause of cardiovascular disease leading to acute coronary syndromes and ischemic strokes. Furthermore, these conditions were responsible annually for a combined 831,272 deaths in the United States and 12.9 million deaths worldwide as reported in a 2010 update [1]. In atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries, a potential cause of ischemic stroke, the main parameter used to determine need for intervention is the degree of vessel stenosis in addition to clinical variables. Carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptoms of transient ischemic attack or stroke attributable to carotid artery disease with at least 70% stenosis has been shown to reduce risk of recurrent stroke [2]. However, retrospective studies of ruptured plaques that produced cerebrovascular events have shown a high incidence of vessels with lower grade stenosis [3–5]. In order to better understand, prevent, and treat the progression of disease, there is an increasing need to characterize the plaque beyond relying solely on severity of vessel stenosis [4,5]. This includes being able to make assessments of the vessel wall microenvironment in much earlier stages of disease, even before significant plaque formation is apparent. Iron presence in atherosclerotic plaques indicates an important role in atherogenesis progression, which is directly associated with up-regulated macrophage uptake of oxidized low density lipoproteins (LDL) [6–8]. A sign of plaque vulnerability, microhemorrhage occurring in atherosclerotic plaque concurrent with macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of aged red blood cells, results in redox-active iron that oxidizes LDL and further facilitates plaque evolution [9,10].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been established as a high-resolution tool for in vivo imaging of the carotid arteries and atherosclerotic plaque [11] using multicontrast signal based techniques such as T1-weighted (W), T2-W, proton density and time-of-flight imaging [11,12]. However, T2* quantification, a MRI relaxation parameter that directly relates with iron presence, has been shown to accurately estimate tissue iron content in the liver and heart [13–15]. In carotid atherosclerosis disease, T2* quantification was able to distinguish symptom-producing plaques from those in asymptomatic patients, and has been associated with plaque microhemorrhage, iron deposition and possible shifts in aggregate iron complexes [16]. Lately, T2* quantification has been used to quantify macrophage uptake of ultra-small paramagnetic iron oxide contrast media as a measure of evaluating the inflammatory burden in atherosclerotic disease [17] and in response with statin therapy [18].

Estimation of T2* is typically accomplished by a monoexponential pixelwise fit of decaying signal intensities observed using a gradient recalled echo (GRE) sequence over increasing echo times (TEs). This traditional method has shown robust results for large areas of tissue [13,14], but when evaluating small vessels such as the carotid arteries and thin areas of myocardium, this method is prone to error from noise, misregistration, partial voxel mixing effects, and invading blood signal in voxels at the boundary of lumen and vessel wall. This makes it difficult to accurately track changes in T2* in a few millimeters thick carotid wall in early stages of plaque formation. As such, there is a need for a revised T2* quantification method to address these errors and provide more reliable and consistent results. We hypothesized that the above mentioned sources of errors could be reduced by sampling a small window of semi-homogeneous regions of tissue for estimation instead of the pixelwise evaluation, and using the estimation's lack of fit to automate the identification and elimination of outliers. Further, we tested this new technique for T2* quantification in agarose phantoms and in the carotid arteries of subjects at risk for atherosclerosis and patients scheduled for carotid endarterectomy.

2. Methods

2.1. Simulations

Simulations were performed to model a single slice of a vessel wall, highlighting the effects of partial volume mixing and misregistration. Vessel walls were modeled as two concentric ellipses with a T2* value of 20 ms in between the ellipses. To simulate wall motion, the vessel wall ellipses were allowed to expand or contract along the x and y-axes up to 5% at random. At the first echo time, the ellipses formed perfect circles with an inner radius of 32 pixels and outer radius of 44 pixels in a 101×101 field-of-view. Extravascular tissue was given a T2* time of 40 ms. Since a dark-blood sequence is being used in practice, only noise should be left in the lumen. Therefore, lumen blood was simulated as a noisy signal instead of following the decay profile from a given T2* time. Noise was chosen to match the desired signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) noise profile for the rest of the image. This image was then resized to 51×51 and 26×26 to reduce spatial resolution using bilinear interpolation.

The signal was calculated for 5 TEs (2.73, 7.49, 12.25, 17.08, 22.42 ms), adding white noise to result in two SNRs, 4 and 10. T2* values were then estimated from each SNR, with and without wall motion, and for each resolution 101×101, 51×51 and 26×26 using the vessel wall in the first echo time as the ideal region of interest (ROI). This simulation was repeated 2000 times and the results averaged together.

2.2. Arterial phantoms

Six phantoms were prepared using different agarose concentrations: 1.5%, 2%, 2.5%, 2.75%, 3% and 3.25% mg/g of water. Agarose was used because it has been shown to decrease T2* relaxation time with increasing concentration [19]. These concentrations were chosen to encompass the expected range of T2* for normal carotid vessel wall at 1.5 T, roughly 30–70 ms. At 3 T, these times would be expected to be shorter. The different concentrations of agarose were used to fill the space between two concentric glass tubes with outer diameters of 5 and 8 mm (Fig. 1) to model the size and basic shape of a short section of carotid artery.

Fig. 1.

Phantom design. The size and shape of the phantoms were designed to simulate the basic size and shape of human carotid arteries. Agarose was used to give T2* values over the expected range of T2* for normal vessel tissue. As a result, these phantoms should be susceptible to similar error sources seen in vivo.

2.3. Phantom imaging

MR images were acquired at both 1.5- and 3-T MRI systems (MAGNETOM, Avanto and Verio; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), using a standard 12-channel body array coil for signal reception and the integrated body-coil for radiofrequency signal transmission. Phantoms were positioned in two sets aligned to the main magnetic field, in an orientation similar to the common carotid artery (CCA). Ten 4-mm-thick slices with 4-mm gap were collected along the length of each phantom. A dark-blood multiecho GRE sequence with five interleaving TEs (2.73, 7.64, 12.5, 17.4 and 22.5 at 1.5 T and 2.73, 7.49, 12.25, 17.08 and 22.42 ms at 3 T), 600 ms TR at 1.5 T and 740 ms TR at 3 T, 0.55×0.55 mm2 in-plane resolution, four averages at 1.5 T and 2 averages at 3 T, and 20° flip angle was used for image acquisitions. Additional averages were used at 1.5 T to obtain a similar signal-to-noise ratio as 3 T. Note that with this in-plane resolution of 0.54×0.54mm2, acquired images will have approximately 3 voxel thick substrate in the phantom cross section.

2.4. In vivo MRI study

Sixteen perimenopausal female subjects (age 48.6±2.7 years) with at least two risk factors for atherosclerosis but no known cardiovascular disease (Table 1), and seventeen patients (14 male, 3 female, 61.5±12.4 years) with carotid atherosclerosis scheduled for carotid endarterectomy (CEA) were enrolled as part of a longitudinal National Institutes of Health-funded study of iron and atherosclerosis (NCT00921011). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects for participation in this institutional review board-approved study. Human subjects were imaged using the 3-T whole-body MR system and a custom-built, eight-channel (four right and four left) phased-array carotid coil (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA).

Table 1.

Perimenopausal subjects characteristics

| Age, years | 48.63±2.70 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 (81) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3(19) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 8(50) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 15 (94) |

Noncontrast angiographic images were obtained in all human subjects using a vascular time-of-flight (TOF) spoiled GRE sequence (21 ms TR, 3.6 ms TE, 1-mm slice thickness, 0.47×0.47mm in-plane resolution). The same sequence was used for both patients and phantoms at 3 T, except for an improved in-plane resolution of 0.47×0.47mm2. In each perimenopausal woman, TOF images were used to prescribe three slices on each side (left, right) orthogonal to the carotid artery. The first slice was prescribed just below the bulb in the CCA, and the other two were prescribed 2.5 and 5 mm above the bifurcation in the internal carotid artery. In each CEA patient, using the TOF acquisition to localize stenosisproducing plaque, three slice locations (center of maximal stenosis, proximal and one each through proximal/distal plaque) were prescribed perpendicular to the vessel. In vivo images for T2* estimation were acquired using the same protocol as that used in phantoms.

2.5. T2* estimation

The signal from a GRE acquisition with sufficiently long TR decays as: Signal=S0exp(−TE/T2*). A pixelwise linear least squares estimation of T2* (pix) was used as a reference technique for comparison with the new proposed test technique. The signal was transformed by a natural logarithm to linearize the signal decay with respect to varying TEs. Simple linear regression of these points was used to obtain the slope of decay, the negative inverse estimate of T2*.

The test technique involved three additional steps to prepare data for estimation:

Weighting of each data point

Collection of a neighborhood of points

Automated detection and deletion of outliers.

Each data point (i.e., signal at each voxel for each echo time transformed by natural logarithm) was weighted between 0 and 1. The weight assigned (W) was a linear combination of two weighting schemes (W1 and W2) with control parameters λ, α and β for fine-tuning the effects of each scheme as follows:

| (1) |

The first weighting scheme gave each point an exponentially decaying weight with increasing TE because of known SNR loss with longer TE times relative to TE0, the first echo time.

| (2) |

The second weighting scheme took advantage of the expectation that the signal at each voxel should decay with longer TE. As a result of misregistration, partial volume mixing and higher noise influence, some points will not decay as expected. For each nondecaying point (ndp), a point whose value is greater than or equal to the previous echo times value, all points at a single voxel were penalized by β/N, where N is the total number of points.

| (3) |

| (4) |

All parameters were optimized by choosing the values that maximized the coefficient of determination, R2, at each voxel. To accomplish this, each argument was iterated independently from 0 to 1 by a 0.01 step, and the set of parameters that optimized R2 was chosen as α, β, λ.

For each voxel in a given ROI, a 3×3 neighborhood of weighted signal intensities was collected over each echo time. If voxels in the 3×3 neighborhood appeared outside the given ROI, they were not collected. The collected set of data points was used in a simple linear regression to estimate T2*. This neighborhood weighted least squares estimate (nbr) of T2* was then assigned to the center voxel of each neighborhood.

Blood flow captured by encroaching ROIs in the lumen, partial volume mixing along vessel boundaries, misregistration of images, noise and other sources contribute to poor goodness of fit with parameter estimation in thin tissue such as the arterial wall. In some cases, the signal at a voxel is unrecoverable from corruption and should not be used to estimate T2* and subsequently characterize tissue. By analyzing the lack of fit, these voxels were identified as outliers and disregarded when estimating T2* for an ROI (nbr−). In this technique, the coefficient of determination, R2, was used to assess goodness of fit and any result less than 0.5 was identified and removed as an outlier. This 0.5 threshold was determined from an analysis of the first 20 images which showed conservation of 70% of the chosen voxels with a threshold of 0.4877, rounded to 0.5, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Outlier thresholding. The threshold for outliers determined using R2 was chosen by analyzing the first 20 images and choosing a threshold that conserved 70% of the chosen voxels. The dashed line indicates the position where this criteria was met, namely with a threshold of 0.4877, which was later rounded up to 0.5.

2.6. Quantitative estimation

A single ROI was drawn for each slice of each phantom, a total of 60 ROIs considered for this study. The mean T2* for each ROI was estimated by both the pix and nbr− methods.

Three experienced observers performed manual drawing of ROIs to estimate vessel wall T2* in each of the 96 slices acquired from perimenopausal patients. Each observer outlined two ROIs for each slice. The first ROI was used to encompass the entire vessel wall, making no attempt to exclude unfavorable voxels. The mean and standard deviation of these regions were recorded as estimated by the pix and nbr− techniques. The second ROI was a manual attempt to avoid noisy and corrupted voxels that would taint the mean estimate of the region by drawing a smaller ROI in a visually-homogeneous region within the vessel wall. The mean and standard deviation of these regions were recorded as estimated by the pix technique. One of the three observers generated ROIs to estimate T2* in each of the 51 slices from CEA patients. The entire visible plaque was included in each ROI and mean and standard deviation of these regions were recorded as estimated by the pix and nbr− techniques.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MATLAB. To evaluate the performance of the old and the proposed T2* estimation techniques the range of mean estimates, mean and standard deviation were calculated. Pearson correlation was used to compare interobserver agreement. Bland-Altman plot were also generated to characterize the interobserver variability between each pair of observers.

3. Results

3.1. Optimization

Optimization of the control parameters for each data set resulted in α values of 0.689±0.317, β values of 0.147±0.278 and λ values of 0.746±0.325.

3.2. Simulations

The results of the simulations using pix and nbr− are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. Applying neighborhood estimation, without weighting or outlier detection, on average increased accuracy by 31% over pix. Applying weights provided an additional 16% improvement. Finally, applying outlier deletion yielded an additional 26% improvement for an average error of less than 4%. The largest error was seen with wall motion and an SNR of 4, where pix had an average error of 255% and nbr− had an average error of 9%. When considering only those simulations using wall motion, outlier deletion was responsible for 40% of the improvement, while neighborhood provided 36% and weighting only 24%. On average, 8 outliers were detected at 26×26 resolutions and as many as 1087 at 101×101 resolutions with 84% of these along the lumen border and 13% along the outer boundary of the vessel wall.

Table 2.

Simulation results demonstrating variability within each slice

| Resolution | SNR | Wall Motion | pix | nbr − |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101×101 | 4 | Yes | 70.9±17.2e2 | 18.3±2.49 |

| No | 23.6±54.6 | 18.3±2.58 | ||

| 10 | Yes | 76.9±173 | 19.7±1.11 | |

| No | 20.2±3.46 | 19.7±1.06 | ||

| 51×51 | 4 | Yes | 36.5±280 | 19.1±2.95 |

| No | 27.1±85.0 | 18.9±2.83 | ||

| 10 | Yes | 22.2±6.55 | 21.0±2.30 | |

| No | 21.3±4.61 | 20.4±1.50 | ||

| 26×26 | 4 | Yes | 53.5±385 | 19.1±2.98 |

| No | 29.0±70.3 | 18.9±2.91 | ||

| 10 | Yes | 22.2±6.09 | 20.8±1.63 | |

| No | 21.6±5.03 | 20.4±1.35 |

Results reported as the mean estimate over 2000 iterations±the average standard deviation within each slice.

Table 3.

Simulation results demonstrating between slice variability

| Resolution | SNR | Wall Motion | pix | nbr − |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101×101 | 4 | Yes | 70.9±301.10 | 18.3±0.16 |

| No | 23.6±25.19 | 18.3±0.14 | ||

| 10 | Yes | 76.9±172.37 | 19.7±0.08 | |

| No | 20.2±0.06 | 19.7±1.06 | ||

| 51×51 | 4 | Yes | 36.5±187.33 | 19.1±0.14 |

| No | 27.1±6.64 | 18.9±0.28 | ||

| 10 | Yes | 22.2±0.74 | 21.0±0.45 | |

| No | 21.3±0.15 | 20.4±1.50 | ||

| 26×26 | 4 | Yes | 53.5±31.93 | 19.1±0.59 |

| No | 29.0±13.28 | 18.9±0.57 | ||

| 10 | Yes | 22.2±0.56 | 20.8±0.34 | |

| No | 21.6±0.30 | 20.4±0.25 |

Results reported as the mean estimate over 2000 iterations±the standard deviation of the mean estimate over 2000 iterations.

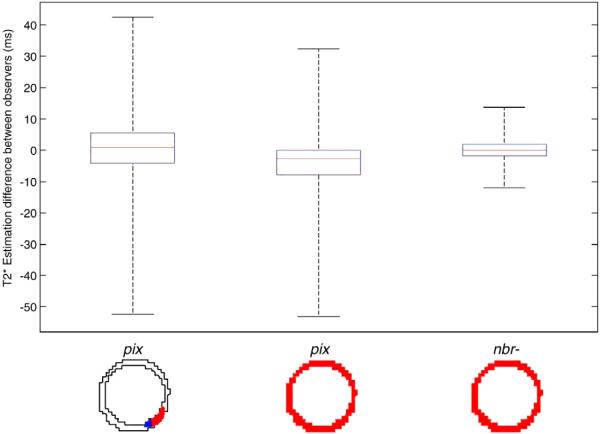

3.3. Arterial phantoms

The reference technique, pix, yielded T2* estimates in the range 37.95–92.07 ms at 1.5 T and 36.24–106.30 ms at 3 T. On average, the nbr− means for each phantom were always lower than the pix means and were within the expected range at both 1.5 T with 34.35–71.63 ms and 3T with 33.90–66.82 ms. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the values at 3 T were always lower than those at 1.5T using the nbr− technique, whereas in only two instances pix estimate averaged lower T2* times at 3 T than 1.5 T, contrary to expectations. Shown in the error bars in Fig. 3, the nbr− test technique also consistently yielded a smaller variability than the pix reference technique with an average variability of 5.57 versus 35.83 ms using the pix technique.

Fig. 3.

Phantom study results showing the mean and standard deviation of T2* estimates for all six phantoms. The plot shows a significant reduction in variability using the new nbr− technique especially for higher values of T2*. The reference technique, pix, also inaccurately estimated the 3T T2* values to be greater than 1.5 T with 1.5%, 2%, 2.5% and 3% agarose.

3.4. In vivo studies

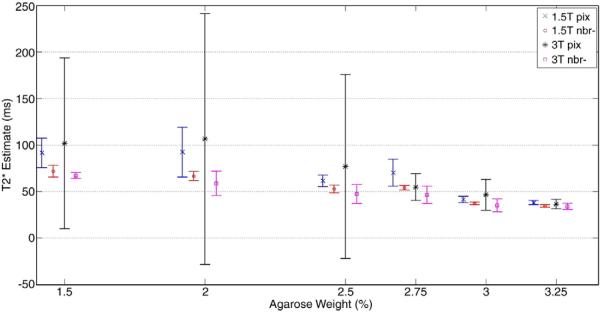

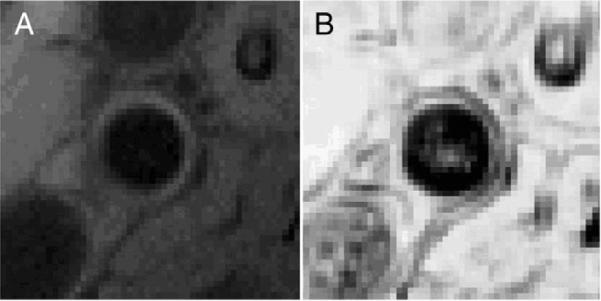

For perimenopausal patients, the reference technique, pix using a visually-homogeneous ROI, yielded T2* values in the range 10.51–70.84ms. On average, these ROIs included 24 voxels and had a minimum of 10 voxels each. The mean difference between the 3 pairs of operators was 3.22±11.44ms (r=0.49). Using the entire vessel wall yielded similar results between observers with 5.27±10.12ms (r=0.78), but a larger range of 13.14–125.14 ms. On average these ROIs included 164 voxels. The new technique, nbr− using the full vessel ROI, resulted in T2* estimates in a tighter range 12.60–38.28. The mean voxel count for detected outliers was 30. As expected, larger ROIs encroaching into boundary voxels saw larger outlier detection most likely due to the partial volume mixing at tissue boundaries especially along the lumen edge where blood flow is present. This can be visualized in the hypointense voxels of the R2 map near the lumen borders in Fig. 4. The mean difference between observers was consistently lower, on average 2.85±2.73 ms (r=0.83). The direct comparison of these results can be visualized in Fig. 5. Overall there was a 4.2-fold decrease in the 95% confidence intervals using the test technique over the reference technique and manual voxel removal, and a 3.7-fold decrease as compared to the reference method over the entire vessel wall. The Bland–Altman plots in Fig. 6 shows the distribution of differences between observers 1 and 3. Note that larger differences tended to occur for higher mean values of T2*. This is typically indicative of noisy or corrupted data points in an ROI that yielded large, erroneous T2* values with poor goodness of fit.

Fig. 4.

(A) Cross sectional view of the magnitude image for the right common carotid of one patient showing and (B) the calculated R2 map showing the goodness of fit at each voxel. Hypointense boundaries are emphasized in the R2 map due to the poor fit of T2* at tissue boundaries.

Fig. 5.

Summary of interobserver variability between three pairs of observers. The reference technique, pix, demonstrates similar results whether or not there was a manual attempt to avoid error with wide confidence intervals of 22.88 ms and 20.24 ms and maximum differences near 50 ms. The test technique, nbr−, showed significant improvements with an average confidence interval of only 4.46 ms and a maximum difference of 16 ms.

Fig. 6.

Bland–Altman plots between Observers 1 and 3 for (A) pix technique and the smaller homogeneous ROI, (B) pix technique using the full vessel ROI and (C) nbr− technique and full vessel ROI. All three plots demonstrated a tighter clustering for lower T2* values between 15 and 40 ms. Despite attempts to avoid error prone voxels with the pix technique, the smaller homogeneous ROI still resulted in a wide confidence interval of 18ms only slightly improved over the fully vessel ROIs interval of 24 ms. The nbr− method yielded both a shorter range of values as well as significantly narrower confidence interval of only 7 ms.

For CEA patients, pix yielded T2* values in the range 8.60–158.25 ms with a mean of 25.28±21.55ms and an average standard deviation of 24.91 ms. The new technique, nbr− yielded T2* value in the range 8.00 to −.40 ms with a mean of 20.17±5.55ms and an average standard deviation of 5.57 ms. The regions drawn included a mean of 208 voxels with 19 outliers detected on average. The mean difference between the two measures was 6.12±18.17 ms. A summary of the resulting estimations is visualized in Fig. 7, showing similar distributions for both techniques with the exception of several statistical outliers above the 99th percentile using the pix method. Removing these outliers, pix yielded T2* estimates in the range 8.60–39.09 ms with a mean of 20.45±7.38 ms.

Fig. 7.

Boxplot of CEA results showing a similar distribution of T2* estimates for both pix and nbr− with the exception of several statistical outliers above the 99th percentile (indicated by +) seen using the pix technique.

4. Discussion

In this work, we have developed a novel method for T2* estimation in small regions such as carotid arterial wall and showed improved accuracy in simulations and greater reproducibility in both phantoms as well as in vivo human MRI experiments. Estimating T2* pixel by pixel as done in the reference method essentially requires perfect registration of images. As seen in the carotid artery, even small changes in vessel diameter can cause different tissue or blood signal intensity to replace the vessel wall in images at different echo times. Misregistration may be reduced by the current sequence design using interleaving TEs [20], but even with perfect registration, most of these voxel samples lie along the boundary of the vessel wall and are most likely susceptible to partial volume mixing between surrounding tissue and blood flow. Especially in the case of arterial blood with a much longer T2*, this results in a gross overestimation of T2* that can dominate the vessel cross section being analyzed. By applying additional postprocessing methods to the estimation as described by the test method, nbr−, the influence of such error sources was significantly reduced.

The high α and λ values in optimization of the weighting scheme suggest that W1 provides more significant improvements to R2 than W2. Furthermore, simulation results suggest the biggest improvements come from neighborhood estimations, then outlier detection and deletion, and finally the additional weighting schemes. However, outlier deletion becomes more important when dealing with boundary voxels that are more susceptible to misregistration and partial volume mixing.

The large variance seen in simulations with pix appears to be due to both the misregistration of pixels and partial volume mixing. Stopping wall motion in simulations or using interleaved TEs as in the current sequence design should greatly reduce if not eliminate sources of error from misregistration. However, simulations, phantom and in vivo studies all showed significant variance without the presence of misregistration, presumably due to partial volume mixing along borders and additional noise. The test technique, nbr−, maintains a low variance presumably because both large misregistration and partial volume effects would be eliminated by outlier deletion, and smaller effects would be mitigated by capturing a neighborhood with the majority of the signal containing the tissue of interest.

In phantom studies, a homogeneous substrate with a thin geometry was used to mimic arterial tissue. The reference method showed a high variability between different slice positions, uncharacteristic for a homogeneous material. Similarly, high variability was observed between each simulation estimation with a known T2* value. However, nbr− more accurately characterized both the phantom substrate and simulations as homogeneous as seen by the lower variability between measurements at different slice positions and across all simulations. This decrease in variability was due to the observed improved accuracy of each measurement in simulations at all resolutions, SNR, and with or without wall motion. Presumably then, the reduced variability seen in phantoms would be due to the more accurate estimate of phantom T2* within each slice. Estimates made with nbr− were also within the expected range, following the expectation for shortening T2* with increasing field strength while the reference pix appeared to overestimate T2*, even increasing T2* from 1.5T to 3T.

In vivo patient data displayed a considerably wide confidence interval, 5.27±10.12 ms, when applying the reference method to a thin region of tissue. Manual attempts to remove corrupted voxels only served to increase this interval, 3.22±11.44 ms. Removing these hyperintense regions did provide a range of estimates much closer to that of vascular tissue, which could be misconceived as improved accuracy without observing the goodness of fit of the estimate. The nbr− method reduced these intervals by a factor of 3.7 and 4.2 over pix in the full vessel wall and the manually adjusted regions. It also further reduced the wide range of T2* estimates to a dense clustering of values. It is worth noting that the reference method showed a denser clustering of values within this same range of values as compared to areas with larger interobserver differences, further suggesting this is where the true values should lie.

As expected, when measuring T2* in the larger plaque regions found in CEA patients, pix and nbr− shared a similar range of values, excluding outliers. However, these outliers in the mean estimate were avoided by nbr− by removing outliers at the voxel level. On average, it also reduced the standard deviation of the regional estimate.

While not the focus of this work, this technique could be readily applied to analysis of pre- and post-contrast vessel wall MR images where the contrast agent comprises, for instance, of ultrasmall particles of iron oxide. As evidence supporting the potential utility of these agents in a variety of applications, suitable quantification methods will help both research data analysis and clinical translation.

4.1. Limitations

There is a notable tradeoff with using the nbr− method; primarily it will reduce the in-plane resolution by its kernel size, in this case a 3×3 window. This is the equivalent of smoothing the T2* map. It is also limited to characterization of a single tissue type for each estimate. As would be expected, if you applied this over multiple tissues, blurring will occur near boundaries as additional partial volume mixing with a wider sample window than a single voxel. As with the outlier detection, this should be identified by a significantly poor goodness of fit and could be used to appropriately mark such interfaces.

This new technique does not eliminate the need for manual segmentation of the vessel wall. Manual regions are altered through outlier deletion primarily near the lumen and outer tissue boundaries, making T2* estimates less sensitive to signal from encroaching blood flow and other tissues. However, the identification of this poor goodness of fit near these boundaries does suggest a promising use for this statistic in automatic segmentation of such boundaries.

5. Conclusion

A new method for estimating T2* in tissues using weighted neighborhood estimations and outlier removal provides reproducible estimation in thin arterial wall compared to conventional methods. Taking into account perceived error sources such as partial volume mixing and misregistration, the new method successfully reduced interobserver variability as demonstrated with in vivo human data, improved accuracy in simulations, as well as reduced variability in the homogeneous substrates used in the phantom studies. This decrease in the confidence intervals of tissue T2* estimation should ensure its use as an adequate quantifiable biomarker for longitudinal studies of atherosclerosis.

Footnotes

Grant support: 5R01HL95563 (SVR).

Relationships with Industry: Siemens (SVR, OPS).

References

- [1].Lloyd-Jones D. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;127(7):e46–215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barnett HJ, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1415–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yazdani SK, et al. Pathology and vulnerability of atherosclerotic plaque: identification, treatment options, and individual patient differences for prevention of stroke. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2010;12(3):297–314. doi: 10.1007/s11936-010-0074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Naghavi M, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: part II. Circulation. 2003;108(15):1772–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087481.55887.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Naghavi M, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: part I. Circulation. 2003;108(14):1664–72. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087480.94275.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Haberland ME, Fong D, Cheng L. Malondialdehyde-altered protein occurs in atheroma of Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Science. 1988;241(4862):215–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2455346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Steinberg D. Low density lipoprotein oxidation and its pathobiological significance. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(34):20963–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Steinberg D, et al. Beyond cholesterol. Modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(14):915–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904063201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kolodgie FD, et al. Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(24):2316–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yuan XM, et al. Iron in human atheroma and LDL oxidation by macrophages following erythrophagocytosis. Atherosclerosis. 1996;124(1):61–73. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05817-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cai JM, et al. Classification of human carotid atherosclerotic lesions with in vivo multicontrast magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2002;106(11):1368–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028591.44554.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hatsukami TS, et al. Visualization of fibrous cap thickness and rupture in human atherosclerotic carotid plaque in vivo with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2000;102(9):959–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Anderson LJ, et al. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(23):2171–9. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tanner MA, et al. Multi-center validation of the transferability of the magnetic resonance T2* technique for the quantification of tissue iron. Haematologica. 2006;91(10):1388–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Westwood M, et al. A single breath-hold multiecho T2* cardiovascular magnetic resonance technique for diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;18(1):33–9. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Raman SV, et al. In vivo atherosclerotic plaque characterization using magnetic susceptibility distinguishes symptom-producing plaques. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Howarth SP, et al. In vivo positive contrast IRON sequence and quantitative T(2)* measurement confirms inflammatory burden in a patient with asymptomatic carotid atheroma after USPIO-enhanced MR imaging. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(3):446–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Patterson AJ, et al. In vivo carotid plaque MRI using quantitative T2* measurements with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide particles: a dose-response study to statin therapy. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(1):89–95. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mitchell MD, et al. Agarose as a tissue equivalent phantom material for NMR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1986;4(3):263–6. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(86)91068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Doyle M, et al. Correction of temporal misregistration artifacts in jet flow by conventional phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(6):1256–62. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]