Abstract

Context

Physician referrals play a central role in ambulatory care in the US, yet little is known about national trends in physician referrals over time.

Objective

To assess changes in the rate of referrals to other physicians from physician office visits in the US, 1999 to 2009.

Design, Setting and Participants

We analyzed nationally representative cross-sections of ambulatory patient visits in the US using a sample of 845,243 visits from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys 1993–2009, focusing on the decade from 1999 to 2009.

Main Outcome Measures

Survey-weighted estimates of the total number and percentage of visits resulting in a referral to another physician across several patient and physician characteristics.

Results

From 1999 to 2009, the probability that an ambulatory visit to a physician resulted in a referral to another physician increased from 4.83% to 9.29% (p<0.001), a 92% increase. The absolute number of visits resulting in a physician referral increased 159% nationally over this time, from 40.6 million to 105 million. This trend was consistent across all subgroups examined, except for slower growth among physicians with ownership stakes in their practice (p=0.016) or with the majority of income from managed care contracts (p=0.007). Changes in referral rates varied according to the principal symptoms accounting for patients’ visits, with significant increases noted for visits to PCPs with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and ear/nose/throat complaints.

Conclusion

The percentage and absolute number of ambulatory visits resulting in a referral in the US grew substantially from 1999 to 2009. More research is necessary to understand the contribution of rising referral rates to costs of care.

Introduction

The decision of whether to refer a patient to another physician is an important determinant of health care quality and spending.1–5 Patients who are referred to specialists tend to incur greater health care spending than those who remain within primary care, even after adjusting for health status.5 Although appropriate specialist referrals improve quality, overuse of referrals could increase health care utilization without benefit.4 Referrals and the associated coordination of care for referred patients are also important components of primary care.6

Despite the central role of referrals in health care systems, relatively little research has examined the epidemiology of physician referrals nationally. The existing literature (comprehensively reviewed in reference 10) suggests that referral rates across physicians vary substantially.7–10 Although clear benchmarks are lacking, it is likely that both overuse and underuse are prevalent.10 National trends of physician referral rates in the US have not been characterized since the late 1990s.11 Given the importance of physician referrals and changes in medical practice and knowledge over the ensuing period, it is important to understand how referral patterns have changed nationally since that time. In addition, with the adoption of budgeted payment arrangements as envisioned with Accountable Care Organizations, referrals will likely become a more important focus of both policy makers and managers in their attempts to control health care spending and maintain referrals within organizations.

In this study, we examine ambulatory physician referrals from 1993 to 2009 with a focus on the ten-year period from 1999 to 2009 using nationally representative data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NHAMCS).12,13 We also examine referral rates for specific subgroups of patients and physicians, including an analysis of referrals from primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists according to the category of patients’ primary reason for visit.

Methods

Data Sources

We used data from NAMCS and the outpatient department portion of the NHAMCS from 1993 to 2009. We included all years that recorded referral to another physician from an ambulatory visit and that contained survey design variables to account for their multi-stage sampling design, which included 1999–2009 for both surveys plus 1993–1994 for NAMCS and 1993–1996 for NHAMCS. We focused on the period of continuous data from 1999–2009. Taken together, NAMCS and NHAMCS are representative of outpatient physician visits nationally. Documentation of survey methods are available at the NCHS website.12,14 The Harvard Medical School Committee on Human Studies determined that this study was exempt from review.

Data Collection Procedures

Both NAMCS and NHAMCS use a multi-stage probability sample design to obtain nationally representative samples of ambulatory patient visits in the US.15,16 In the first stage of sampling, 112 primary sampling units (PSUs) were selected among those used in the National Health Interview Survey. For the second stage, physician practices or hospitals were chosen within these PSUs. Finally, in the last stage, physicians or clinics sampled a subset of visits in their practices over a pre-defined time period. In NAMCS, individual physicians sampled a percentage of visits during a one-week period while in NHAMCS, outpatient clinics sampled visits over a 4-week period.

This design enables calculation of national-level estimates and associated standard errors using survey weights provided by the NCHS. From 1993 to 2009, the physician response rate for NAMCS ranged from 58.9 to 73.0 percent, while the clinic response rate to NHAMCS ranged from 72.5 to 95.0 percent. The number of visits sampled annually ranged from 20,760 to 35,586 for a total of 845,243 over the time period 1993–2009 (excluding 1995–1999 for NAMCS and 1997–1998 for NHAMCS).

Data Collection Instruments

Data for each visit is collected using a standardized form completed during each visit. Variables recorded include patient demographic information (age, gender, insurance type, and race), as well as clinical details such as the patient’s reason for visit, physician diagnosis, and visit disposition. The primary outcome in this study was any visit disposition of a referral to another physician. This measure has been shown to correlate with independent observation of physician visits in one study with high specificity and moderate sensitivity, and thus most likely underestimates the number of referrals.12 We also defined a “self-referral” as any visit to a provider that was marked as being “not referred” (which is distinct from referral as the outcome of a visit, as above) and was also a new patient visit. Item level non-response was generally less than 5% across all survey items.

Statistical Analyses

We analyzed referral rates by patient characteristics, physician characteristics, and visit setting. Variables analyzed included age (0–3, >3–18, >18–45, >45–65, and >65 years), sex, race (white, black and other by patient self-report), insurance (private, Medicare, Medicaid and other/uninsured [includes worker’s compensation, self-pay, charity, other, and unknown insurance]), and US region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). In 2005, the survey item for patient insurance type changed from “mark one” form of payment to “mark all that apply,” potentially affecting any analysis of trends that rely on patient insurance type over this period. In addition, in the NHAMCS data, the referral disposition survey item (our main outcome) changed from “referred to other physician/clinic” to “referred to other physician” in 2001. Physician characteristics included whether physicians practice in a solo setting, owned their practice in part or in full, made consults with patients by email or telephone (first collected in 2001), had any form of electronic medical record, and had >50% of their income from managed care contracts or Medicaid (first collected in 2003).

To analyze referral rates by physician specialty, we restricted our analyses to survey data from NAMCS because physician specialty is not available in NHAMCS. We grouped specialties into two broad categories, “primary care,” which included physicians in general and family practice, internal medicine and pediatrics without subspecialty and “specialist,” which included all other physicians (including obstetrics and gynecology, which is grouped as “primary care” in NAMCS).

To explore the possibility that changes in referral rates were disproportionately due to patients with particular diseases or complaints, we examined how often PCPs or specialists referred patients with particular complaints in the first (1999–2002) or final four years (2006–2009) of the continuous period covered in our sample using the first listed, or “most important” “reason for visit” given by patients. We limited these analyses to the 46.5% of visits for which the primary reason for visit involved a symptom (e.g. “chest pain”, but not “general medical examination” or “coronary atherosclerosis”). Using the “reason for visit” coding system developed by the NCHS,17 we categorized all coded symptoms into 12 organ-based categories listed in Tables 3 and 4 (details in the Appendix).

Table 3.

Referral Rates for Adult Visits to PCPs by Reason for Visit Symptom, 1999–2002 vs. 2006–2009

| Symptom Category | Percentage of visits resulting in referral, % (SE) | Top 3 Most Frequently Referred Symptoms (RFV Code) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2002 | 2006–2009 | p-value | ||

| Cardiovascular | 8.46 (1.2) | 14.9 (1.8) | 0.001 | Chest pain (1050.1) Edema (1035.1) Abnormal palpitations (1260.0) |

|

| ||||

| Dermatologic | 10.1 (1.2) | 15.4 (1.3) | 0.03 | Skin rash (1860.0) Skin lesion (1865.0) Other growths of skin (1855.0) |

|

| ||||

| Ear/Nose/Throat | 4.49 (0.65) | 8.51 (0.8) | <0.001 | Earache pain (1355.1) Throat soreness (1455.1) Nasal congestion (1400.0) |

|

| ||||

| General/Viral | 6.11 (1.0) | 8.64 (1.2) | 0.120 | Tiredness/exhaustion (1015.0) Head cold, URI (1445.0) General ill feeling (1025.0) |

|

| ||||

| Gastrointestinal | 12.3 (1.2) | 17.7 (1.6) | 0.007 | Abdominal pain NOS (1545.1) Stomach and abdominal pain (1545.0) Anal-rectal bleeding (1605.2) |

|

| ||||

| Gynecologic/Breast | 21.7 (2.8) | 17.5 (3.0) | 0.14 | Lump or mass of breast (1805.0) Pain or soreness of breast (1800.0) Uterine and vaginal bleeding (1755.0) |

|

| ||||

| Neurologic | 9.64 (1.3) | 13.7 (1.5) | 0.08 | Headache pain in head (1210.0) Vertigo/dizziness (1225.0) Loss of feeling (anesthesia) (1220.1) |

|

| ||||

| Ocular | 18.5 (3.4) | 21.0 (3.3) | 0.54 | Diminished vision (1305.2) Other/unspecified eye symptoms (1335.0) Eye pain (1320.1) |

|

| ||||

| Orthopedic | 12.4 (0.93) | 16.5 (0.99) | 0.003 | Back pain (1905.1) Knee pain (1925.1) Shoulder pain (1940.1) |

|

| ||||

| Psychiatric | 8.37 (1.5) | 11.1 (1.5) | 0.054 | Depression (1110.0) Anxiety/nervousness (1100.0) Insomnia (1135.1) |

|

| ||||

| Pulmonary | 4.98 (0.87) | 6.85 (0.88) | 0.36 | Cough (1440.0) Shortness of breath (1415.0) Labored or difficult breathing (1420.0) |

|

| ||||

| Urologic | 11.6 (2.0) | 12.0 (1.5) | 0.78 | Urinary tract infection NOS (1675.0) Blood in urine (1640.1) Frequency/urgency of urination (1645.0) |

Only visits from patients aged 18 years and older to PCPs are included in this table. P-values calculated with survey-weighted χ2 test. RFV code = code used in the NAMCS “reason for visit” classification. Results in this figure from the NAMCS dataset only (physician specialty data not available in NHAMCS).

Table 4.

Referral Rates for Adult Visits to Specialists by Reason for Visit Symptom, 1999–2002 vs. 2006–2009

| Symptom Category | Percentage of visits resulting in referral, % (SE) | Top 3 Most Frequently Referred Symptoms (RFV Code) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2002 | 2006–2009 | p-value | ||

| Cardiovascular | 7.39 (1.4) | 8.15 (1.6) | 0.51 | Chest pain (1050.1) Chest pressure/tightness (1050.2) Palpitations (1260.0) |

|

| ||||

| Dermatologic | 2.27 (0.33) | 2.43 (0.41) | 0.84 | Skin lesion (1865.0) Skin rash (1860.0) Other growths of skin (1855.0) |

|

| ||||

| Ear/Nose/Throat | 3.76 (0.66) | 7.45 (1.7) | 0.01 | Earache pain (1355.1) Diminished hearing (1345.1) Nasal congestion (1400.0) |

|

| ||||

| General/Viral | 7.87 (1.6) | 8.42 (2.1) | 0.74 | Tiredness exhaustion (1015.0) General weakness (1020.0) General ill feeling (1025.0) |

|

| ||||

| Gastrointestinal | 3.80 (0.66) | 10.6 (2.1) | <0.001 | Abdominal pain NOS (1545.1) Lower abdominal pain (1545.2) Upper abdominal pain (1545.3) |

|

| ||||

| Gynecologic/Breast | 3.68 (0.62) | 5.76 (0.77) | 0.04 | Lump or mass of breast (1805.0) Pelvic pain (1775.1) Pain or soreness of breast (1800.0) |

|

| ||||

| Neurologic | 6.34 (0.78) | 8.37 (0.85) | 0.08 | Headache pain in head (1210.0) Vertigo - dizziness (1225.0) Loss of feeling (anesthesia) (1220.1) |

|

| ||||

| Ocular | 4.71 (0.81) | 5.36 (0.78) | 0.52 | Diminished vision (1305.2) Extraneous vision (1305.3) Eye pain (1320.1) |

|

| ||||

| Orthopedic | 4.60 (0.48) | 8.78 (0.79) | <0.001 | Back pain (1905.1) Low back pain (1910.1) Neck pain (1900.1) |

|

| ||||

| Psychiatric | 1.94 (0.37) | 3.48 (0.55) | 0.005 | Depression (1110.0) Anxiety and nervousness (1100.0) Other psychological symptoms (1165.0) |

|

| ||||

| Pulmonary | 5.70 (1.3) | 7.30 (1.6) | 0.61 | Shortness of breath (1415.0) Cough (1440.0) Labored or difficult breathing (1420.0) |

|

| ||||

| Urologic | 3.13 (0.65) | 4.65 (0.96) | 0.12 | Involuntary urination (1655.1) Blood in urine (1640.1) Frequency and urgency of urination (1645.0) |

Only visits from patients aged 18 years and older to specialist physicians are included in this table. P-values calculated with survey-weighted χ2 test. RFV code = code used in the NAMCS “reason for visit” classification. Results in this figure from the NAMCS dataset only (physician specialty data not available in NHAMCS).

We calculated weighted numbers of visits, referral rates and their standard errors taking account of the multistage probability design as suggested by NCHS using the survey (v. 3.22) package in the programming language R (v. 2.11).18,19. We used US Census data provided in the NAMCS documentation to calculate visits per 1000 persons. As NCHS recommends, we did not include any estimates with a relative standard error (defined as the standard error divided by the estimate) of greater than or equal to 30 percent or sample sizes of 30 or fewer visits, as these values are considered unreliable by NCHS standards.

We tested for trends across time using survey-weighted logistic regression by estimating the p-value of the coefficient for year as an explanatory variable for the outcome of physician referral disposition across the relevant sub-group. Trend tests were evaluated across the interval from 1999–2009. We evaluated for the difference between trends for physician characteristics using analysis of covariance, including an interaction term with year. We evaluated the difference in referral rates by symptom category across the 1999–2002 and 2006–2009 time periods with a survey-weighted χ2 test. All statistical tests were two-tailed with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

In the ten-year period from 1999 to 2009, the probability that a physician visit resulted in a referral to another physician (“referral rate”) increased from 4.83% to 9.29% (p<0.001), a 92% increase (Table 1). In the same time period, the total number of ambulatory visits in the US increased from 841 to 1,130 million per year, or 3,040 to 3,720 visits per 1,000 persons annually. Combined with a national trend of increasing numbers of ambulatory visits, this led to a 159% increase in the absolute number of visits resulting in a physician referral nationally, from 40.6 million in 1999 to 105 million in 2009. Referral rates for Medicare patients more than doubled (4.15% to 9.74%, p<0.001) and, combined with the increase in the number of visits annually resulted in an increase of over 350% in the number of visits resulting in a referral for Medicare beneficiaries.

Table 1.

Number of Ambulatory Visits, Referrals, and Referral Rates in the US by Patient and Practice Characteristics, 1999–2009

| Year | Ambulatory Visits, millions (SE) | Percentage of Ambulatory Visits Resulting in Referral, % (SE) | Ambulatory Visits Resulting in Referral, millions (SE) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2009 | 1999 | 2009 | 1999 | 2009 | ||

| All | 841 (65.6) | 1130 (94.7) | 4.83 (0.26) | 9.29 (0.48) | 40.6 (3.8) | 105 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 0–3 | 52.1 (5.4) | 69.4 (8.1) | 3.74 (0.79) | 4.93 (0.71) | 1.95 (0.5) | 3.42 (0.6) | 0.124 |

| >3–18 | 105 (9.6) | 137 (12.9) | 4.69 (0.54) | 7.64 (0.82) | 4.93 (0.7) | 10.5 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| >18–45 | 257 (22.0) | 287 (25.1) | 5.01 (0.39) | 9.98 (0.71) | 12.9 (1.4) | 28.7 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| >45–65 | 223 (18.2) | 345 (31.1) | 5.43 (0.49) | 9.75 (0.58) | 12.1 (1.5) | 33.7 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| >65 | 205 (16.7) | 295 (25.6) | 4.30 (0.47) | 9.86 (0.72) | 8.79 (1.2) | 29.1 (3.2) | 0.004 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 497 (40.1) | 669 (55.3) | 4.55 (0.25) | 9.30 (0.51) | 22.6 (2.3) | 62.2 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Female | 345 (26.3) | 465 (40.1) | 5.23 (0.37) | 9.28 (0.52) | 18.0 (1.8) | 43.1 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 718 (57.8) | 947 (80.7) | 4.91 (0.28) | 9.01 (0.47) | 35.3 (3.5) | 85.3 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Black | 91.8 (10.2) | 135 (17.4) | 4.60 (0.56) | 11.2 (0.95) | 4.22 (0.6) | 15.1 (2.4) | 0.014 |

| Other | 31.3 (7.2) | 51.7 (6.4) | 3.53 (0.85) | 9.44 (1.22) | 1.11 (0.2) | 4.88 (0.8) | 0.108 |

| Insurance Type | |||||||

| Private | 451 (37.9) | 594 (50.1) | 4.90 (0.32) | 8.95 (0.55) | 22.1 (2.4) | 53.1 (5.1) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 169 (15.2) | 281 (25.8) | 4.15 (0.38) | 9.74 (0.74) | 7.02 (0.9) | 27.3 (3.3) | 0.003 |

| Medicaid | 76.7 (8.9) | 144 (15.7) | 4.95 (0.53) | 9.24 (0.99) | 3.80 (0.6) | 13.3 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Other/Uninsured | 145 (12.5) | 116 (12.0) | 5.33 (0.70) | 9.99 (1.02) | 7.72 (1.3) | 11.5 (1.8) | 0.014 |

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast | 193 (28.8) | 196 (38.5) | 4.51 (0.56) | 9.49 (1.27) | 8.70 (1.7) | 18.6 (4.1) | 0.128 |

| Midwest | 177 (27.8) | 259 (40.1) | 5.11 (0.58) | 9.96 (0.97) | 9.04 (1.7) | 25.8 (4.4) | 0.001 |

| South | 278 (42.4) | 449 (65.8) | 4.64 (0.40) | 8.93 (0.74) | 12.9 (2.4) | 40.1 (7.1) | 0.020 |

| West | 193 (30.1) | 230 (39.3) | 5.16 (0.60) | 9.07 (1.08) | 9.97 (1.8) | 20.9 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Practice Setting | |||||||

| Office-Based | 757 (59.5) | 1040 (87.7) | 4.36 (0.28) | 8.61 (0.47) | 33.0 (3.4) | 89.4 (8.8) | 0.001 |

| Outpatient Dept. | 84.6 (9.7) | 96.1 (12.1) | 8.99 (0.99) | 16.6 (1.80) | 7.61 (1.0) | 16.0 (2.6) | 0.002 |

p-values calculated using logistic regression for trend over interval from 1999–2009 in each subgroup.

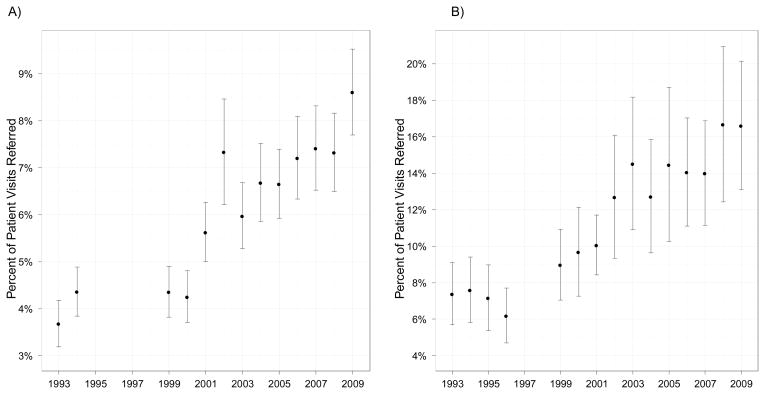

The increase in referral rates was significant for both office-based physicians and outpatient department-based physician practices. In office-based physician practices, physician referral rates increased 97% from 1999 to 2009 (4.36% to 8.61%, p=0.004, Figure 1A). Referral rates in outpatient department-based practices had a similar 85% increase from 8.99% to 16.6% (p<0.001) despite a baseline referral rate more than twice as high as office-based physicians (Figure 1B). During this period, patient “self-referrals” to physicians fell from 6.0% to 2.8% of all visits or a decrease from 50.7 million to 31.3 million self-referred visits nationally from 1999 to 2009 (p<0.001 for trend). In Figure 1, referral rates from 1993–1994 (NAMCS) and 1993–1996 (NHAMCS) are included for historical perspective.

Figure 1. Referral Rates in the US, 1993–2009, by Practice Setting.

Fig. 1A shows referral rates in the US for physicians in office-based practices (NAMCS), while Fig. 1B shows referral rates for physicians in hospital outpatient department-based practices (NHAMCS). Data on referral rates not available from 1995–1999 for NAMCS (Fig. 1A) and 1998–1999 for NHAMCS (Fig. 1B). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Physicians with an ownership stake in their practice had a significantly smaller increase in referral rates than other physicians, only growing 78% from 4.23% to 7.54% compared to a 139% increase for non-owner physicians (4.65 to 11.1% p=0.016; Table 2). Physicians who reported that >50% of their income came from managed care contracts also had lower growth in referral rates (p=0.007, Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of Ambulatory Visits, Referrals, and Referral Rates in the US by Physician Characteristics, 1999–2009

| Year | Ambulatory Visits, millions (SE) | Percentage of Ambulatory Visits Resulting in Referral, % (SE) | Ambulatory Visits Resulting in Referral, millions (SE) | p-value for time trend | p-value for difference in trends | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2009 | 1999 | 2009 | 1999 | 2009 | |||

| Solo Practice | ||||||||

| No | 494 (42.4) | 701 (66.2) | 4.87 (0.37) | 9.37 (0.59) | 24.1 (2.8) | 65.7 (7.4) | <0.001 | 0.392 |

| Yes | 263 (25.7) | 336 (33.3) | 3.41 (0.44) | 7.03 (0.50) | 8.95 (1.6) | 23.7 (2.9) | <0.001 | |

| MD Full or Part Owner? | ||||||||

| No | 241 (24.5) | 315 (34.5) | 4.65 (0.49) | 11.1 (0.94) | 11.2 (1.7) | 34.9 (4.8) | <0.001 | 0.016 |

| Yes | 516 (44.2) | 723 (61.0) | 4.23 (0.36) | 7.54 (0.55) | 21.8 (2.8) | 54.5 (5.9) | <0.001 | |

| E-mail Patient Consults? | 2001* | 2001* | 2001* | |||||

| No | 816 (66) | 962 (83.1) | 5.43 (0.34) | 8.55 (0.49) | 44.3 (4.2) | 82.2 (8.4) | <0.001 | 0.759 |

| Yes | 64.7 (14) | 76.0 (13.7) | 8.22 (1.72) | 9.43 (1.64) | 5.32 (1.8) | 7.16 (1.7) | 0.427 | |

| Telephone Patient Consults? | ||||||||

| No | 307 (27.9) | 501 (48.1) | 5.18 (0.51) | 8.40 (0.73) | 15.9 (2.2) | 42.1 (5.3) | 0.008 | 0.915 |

| Yes | 574 (53.1) | 537 (54.7) | 5.87 (0.47) | 8.81 (0.61) | 33.7 (3.8) | 47.3 (5.6) | <0.001 | |

| Electronic Medical Records | 2003* | 2003* | 2003* | |||||

| No | 758 (65.9) | 690 (58.8) | 5.97 (0.39) | 8.45 (0.57) | 45.3 (5.0) | 58.3 (6.5) | 0.001 | 0.697 |

| Yes | 148 (22.2) | 348 (41.7) | 6.03 (0.78) | 8.94 (0.83) | 8.90 (1.8) | 31.1 (4.6) | 0.030 | |

| >50% Income Managed Care? | ||||||||

| No | 608 (56.9) | 650 (58.7) | 5.50 (0.42) | 8.70 (0.58) | 33.4 (4.0) | 56.6 (6.6) | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| Yes | 298 (32.7) | 388 (41.1) | 6.94 (0.59) | 8.46 (0.73) | 20.7 (3.2) | 32.8 (4.4) | 0.540 | |

| >50% Income Medicaid? | ||||||||

| No | 872 (72.5) | 966 (82.1) | 5.97 (0.37) | 8.82 (0.50) | 52.1 (5.4) | 85.2 (8.5) | <0.001 | 0.365 |

| Yes | 33.7 (7.6) | 72.3 (14.1) | 6.20 (2.30) | 5.77 (0.95) | 2.09 (1.0) | 4.17 (1.1) | 0.678 | |

P-values for time trend calculated using logistic regression for trend over interval from the earliest year available to 2009 in each subgroup. P-values for difference in trends within each group calculated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

For the e-mail and telephone consult characteristics, the earliest year available was 2001, for the electronic medical record, HMO, and Medicaid variables, 2003 was the earliest year.

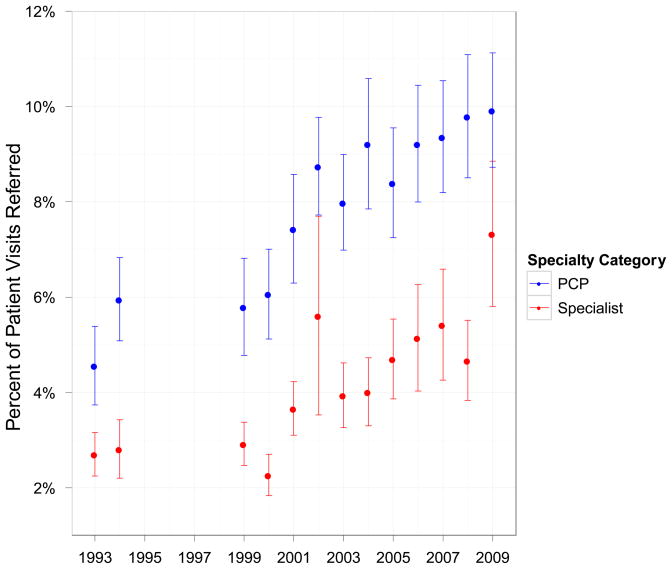

Both specialists and PCPs saw large changes in their referral rates from 1999–2009, (2.92% to 7.33% for specialists and 5.79% to 9.92% for PCPs, p<0.001 for both, Figure 2). This corresponds to an absolute change from 10.9 million to 38.4 million visits to specialists resulting in a referral versus 22.0 million to 50.9 million visits to PCPs resulting in a referral. Despite these increases, the proportion of all visits to specialists remained relatively stable, increasing from 49.9% in 1999 to 50.5% in 2009.

Figure 2. Referral Rates in the US for Office-Based Physicians, 1993–2009, by Specialty.

Results in this figure from the NAMCS dataset only (physician specialty data not available in NHAMCS). Data not available from 1995–1998 on referral rates. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

For PCPs, changes in referral rates varied according to the principal symptom accounting for a patient’s visit. Visits with primary complaints in the cardiovascular (8.46% to 14.9%, p=0.001), dermatologic (10.1% to 15.4%, p=0.03), ear/nose/throat (4.49% to 8.51%, p<0.001), gastrointestinal (12.3% to 17.7%, p=0.007), and orthopedic (12.4% to 16.4%, p=0.003) categories saw significant increases between the 1999–2002 and 2006–2009 intervals. In contrast, other kinds of visits to PCPs, such as general/viral, gynecologic/breast, and ocular had modest, statistically non-significant changes over the time period examined (Table 3). Specialist physicians had a significant increase in referral rate for three symptom categories in common with PCPs, ear/nose/throat (3.76% to 7.45%, p=0.01), gastrointestinal (3.80% to 10.6%, p<0.001) and orthopedic (4.60% to 8.78%, p<0.001), in addition to an increase in two categories not shared with PCPs, gynecologic/breast (3.68% to 5.76%, p=0.04) and psychiatric (1.94% to 3.48%, p=0.005) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we find a marked increase in referral rates nationally from 1999 to 2009, with the absolute number of ambulatory visits resulting in a referral more than doubling over this time period. These trends are consistent across primary care and specialist physicians as well as office-based and outpatient-department based physicians. The observed increase in referral rates does not appear to be predominantly driven by a particular patient demographic creating more demand for referrals. This evolution in care patterns may be playing a role in the rising trajectory of health care spending in the US, as referrals to specialists may lead to increased use of higher-cost services.

One potentially contradictory finding is that despite the marked increase in the referral rate, the proportion of all ambulatory visits to specialists has remained stable around 50%. This can be explained in a few ways: first, because specialists refer to PCPs,20 referrals do not always imply a new specialist visit; second, self-referral rates decreased by about 19 million, which could explain up to 30% of the total increase in referral rate and lastly, the number of ambulatory visits per 1000 persons in the US increased markedly in the 1999–2009 interval. Therefore, a possible consequence of increasing referral rates is a greater number of ambulatory visits for the average person, both in the primary care and specialist setting. It is also worth noting that only about half of referrals actually result in a completed appointment.21,22

There are several explanations for the observed increase in rates of referrals. One possibility is that care is becoming increasingly complex, thereby requiring ever more care by specialized physicians.23,24 We find some evidence to support this hypothesis in Table 3, which shows that PCPs became more likely to refer patients with certain chief complaints but not others across the interval from 1999–2002 to 2006–2009. For instance, we observe significant changes for patients with cardiovascular or dermatologic complaints, but not in areas that are more comfortably within the scope of primary care, such as general/viral symptoms. Specialist physicians saw no significant change in referral rates in these areas. Likewise, chief complaints outside the traditional spectrum of primary care, such as ocular or gynecologic/breast symptoms, had a consistently high likelihood of referral from PCPs, but had no significant change in referral rate. This suggests that some areas, such as cardiovascular and ear/nose/throat complaints, may be increasingly outside the expertise or clinical portfolio of primary care providers to manage alone. Other areas, such as gastrointestinal and orthopedic complaints, had consistently increasing referral rates for PCPs and specialists, which may reflect increasing influence of those specialties in health care markets.

A related hypothesis is that physicians are increasingly faced with more to do during the typical visit, despite no meaningful change in appointment durations in over two decades.25 Patients require more medications and more frequently have one or more chronic medical conditions.26 Moreover, screening and preventive recommendations have grown dramatically during this time period. As a result, although visit time has remained stable, physicians, and in particular PCPs, may not have enough time to address each patient issue, resulting in increased rates of referrals. Lastly, increasing numbers of specialists and availability of specialist physicians may help drive referral rates.27 This may help explain why hospital-based physicians in closer proximity to specialists in the hospital setting have referral rates close to double that of office-based physicians.

We also find that physicians who had an ownership stake in their practice had lower increases in referral rates compared to non-owner colleagues, which might reflect a financial incentive for these physicians to keep patients’ care within their practice. Supporting the potential influence of economic incentives on referral rates, physicians with greater than 50% of their income from managed care contracts also had slower growth in referral rates. Another notable result is that patients in the 3–18 year-old age group have a higher referral rate in 1999 than >65 year old patients, though this difference disappears by 2009. The >65 year old age group has a lower referral rate than younger adults in 1999 and 2009, which may reflect that these patients have generally already made relationships with providers at an earlier age for their chronic illnesses.

It is unclear whether the trends we observe reflect a change in the appropriateness of referrals over time. This is due in part to the fact that little guidance exists on how to optimally define the appropriate use of referrals. A recent review of the literature concluded that appropriateness of referrals has yet to be studied effectively.10 The complexity of referral appropriateness is compounded by the multiple roles that specialists can play in the care of a patient, ranging from consultative to procedural to co-managing a complex condition.6

This study is subject to several limitations. First, we rely on the accuracy of reporting in the NAMCS and NHAMCS instruments to measure referrals, which has been shown in one study to have high specificity but only moderate sensitivity.12 The survey question for this field also changed in 2001 for NHAMCS, from “referred to physician/clinic” to “referred to physician.” We would expect this wording change to narrow the potential range of reasons to check this category and bias our findings toward the null. Thus, the referral rates in this study are, if anything, likely underestimating national rates. Second, we have no information on why a referral has been made or to whom. This is particularly relevant for the results in Tables 3 and 4, where we rely on the assumption of a relationship between a patient’s primary reason for visit and the reason for referral. We believe that on average, it is clinically reasonable to assume that a referral has a high likelihood of relating to the primary reason that brought a patient to visit the doctor, but this may not always be the case. Another limitation is that the response rate to NAMCS has fluctuated with a gradual decline over the time period from 1999–2009. We believe that this is not likely to explain much of the change seen, especially given that the response rate for NHAMCS has been stable from 1999–2009. There is also a possibility that our findings could have been affected by changing demographic characteristics of the population. Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 1999–2008, however, shows that the demographic composition by insurance status and income of Americans reporting that they had one or more office visits to a physician in the past year were stable (authors’ analysis, data from http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/). Lastly, we rely on the accuracy of the sampling strategy of NAMCS and NHAMCS to produce nationally representative estimates.

In conclusion, we find that referrals in the US grew rapidly from 1999 to 2009, with potential implications for health care spending. As federal and state policymakers consider policies for reforming the health care system, developing methods to measure referral appropriateness and using these to promote appropriate referrals may be an important strategy for controlling growth in health care spending.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Barbara McNeil for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: Drs. Barnett and Landon had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Barnett, Song, Landon

Acquisition of data: Barnett

Analysis and interpretation of data: Barnett, Song, Landon

Drafting of the manuscript: Barnett, Song, Landon

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Barnett, Song, Landon

Statistical analysis: Barnett

Obtained funding: none obtained.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Barnett, Song Study supervision: Landon

References

- 1.Glenn JK, Lawler FH, Hoerl MS. Physician referrals in a competitive environment. An estimate of the economic impact of a referral. JAMA. 1987 Oct 9;258(14):1920–1923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulware LE, Troll MU, Jaar BG, Myers DI, Powe NR. Identification and referral of patients with progressive CKD: a national study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006 Aug;48(2):192–204. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu AW, Young Y, Skinner EA, et al. Quality of care and outcomes of adults with asthma treated by specialists and generalists in managed care. Archives of internal medicine. 2001 Nov 26;161(21):2554–2560. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohoe MT. Comparing generalist and specialty care: discrepancies, deficiencies, and excesses. Archives of internal medicine. 1998 Aug 10–24;158(15):1596–1608. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Zubkoff M, et al. Variations in resource utilization among medical specialties and systems of care. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1992 Mar 25;267(12):1624–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrest CB. A typology of specialists’ clinical roles. Archives of internal medicine. 2009 Jun 8;169(11):1062–1068. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franks P, Zwanziger J, Mooney C, Sorbero M. Variations in primary care physician referral rates. Health services research. 1999 Apr;34(1 Pt 2):323–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franks P, Williams GC, Zwanziger J, Mooney C, Sorbero M. Why do physicians vary so widely in their referral rates? Journal of general internal medicine. 2000 Mar;15(3):163–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.04079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinchen K, Cooper L, Levine D, Wang N, Powe N. Referral of patients to specialists: factors affecting choice of specialist by primary care physicians. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2(3):245–252. doi: 10.1370/afm.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011 Mar;89(1):39–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrest CB, Reid RJ. Passing the baton: HMOs’ influence on referrals to specialty care. Health affairs (Project Hope) 1997 Nov-Dec;16(6):157–162. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.6.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilchrist VJ, Stange KC, Flocke SA, McCord G, Bourguet CC. A comparison of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) measurement approach with direct observation of outpatient visits. Medical care. 2004 Mar;42(3):276–280. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114916.95639.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed March 16, 2011];National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) List of Publications. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/publist9-10-10.pdf.

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed March 16, 2011];NAMCS/NHAMCS Main Site. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm.

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics. Public Use Micro-data File Documentation, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2008. Hyattsville, MD: National Technical Information Servie; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics. Public Use Micro-data File Documentation, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2008. Hyattsville, MD: National Technical Information Servie; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider DAL, McLemore T. A Reason For Visit Classification for Ambulatory Care. Vital Health Stat. 1979;2(78) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R, (version 2.11): A language and environment for statistical computing [computer program]. Version 2.11. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumley T. Analysis of complex survey samples. Journal of Statistical Software. 2004;9(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnett M, Keating N, Christakis N, O’Malley A, Landon B. Reasons for Choice of Referral Physician Among Primary Care and Specialist Physicians. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1861-z. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner M, Perkins AJ, Callahan CM. Errors in completion of referrals among older urban adults in ambulatory care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010 Feb;16(1):76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiner M, El Hoyek G, Wang L, et al. A web-based generalist-specialist system to improve scheduling of outpatient specialty consultations in an academic center. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009 Jun;24(6):710–715. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0971-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoff T. Practice under pressure: primary care physicians and their medicine in the twenty-first century. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassel CK, Reuben DB. Specialization, subspecialization, and subsubspecialization in internal medicine. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Mar 24;364(12):1169–1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1012647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mechanic D, McAlpine DD, Rosenthal M. Are patients’ office visits with physicians getting shorter? The New England journal of medicine. 2001 Jan 18;344(3):198–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2009 Jan-Feb;28(1):15–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher ES, Goodman DC, Skinner aJS. Tracking the Care of Patients with Severe Chronic Illness: The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care 2008. Apr 3, 2008. pp. 1–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]