ATP has become a personal obsession. I am arriving at this exciting field after working in exocytosis for decades. ATP is a natural component of chromaffin granules, the secretory organelle of adrenal chromaffin cells. These cells release catecholamines to the bloodstream as a response to stress stimuli [1]. Natural adrenal catecholamines comprise adrenaline and noradrenaline stored at amazingly high concentrations (0.5–1 M). These huge amounts together with the other soluble components (chromogranins, calcium, ascorbate, protons and ATP) should theoretically promote osmotic forces of about 1,500 mOsm! [2, 7]. To avoid the osmotic lysis of secretory vesicles, the solutes must be aggregated to reduce the tonicity; the main candidates to promote the aggregation have been chromogranins, the most abundant soluble proteins present in chromaffin granules and large dense core vesicles.

In an effort to demonstrate this vesicular role of chromogranins, we have studied the exocytotic responses in chromaffin cells from mice lacking in these proteins. Although the absence of chromogranins halves the vesicular amine content and impairs the ability of these secretory vesicles to uptake newly formed catecholamines, the concentration of catecholamines is still very high [5]. This fact made me recall an old paper performed by Ed Westhead's group (University of Massachusetts) in the mid-1980s. Using just an osmometer, they analyzed the osmotic properties of ATP/catecholamine mixtures reporting that this combination behaves as a non-ideal solute resulting in a reduction in the osmolaritay [6]. Recently, Dr. Westhead visited my laboratory for reanalyzing those results on the light of recent data. ATP is co-stored in chromaffin granules with catecholamines at proportion that ranges 1:2.5–6. With these numbers in mind, we obtained the data shown in Fig. 1. After reading the story of co-transmission [3], I guessed that ATP is not co-released with catecholamines; it is just the other way round: amines, peptides, amino acids and practically all of the secreted substances are co-released with ATP, who arrived first (Table 1).

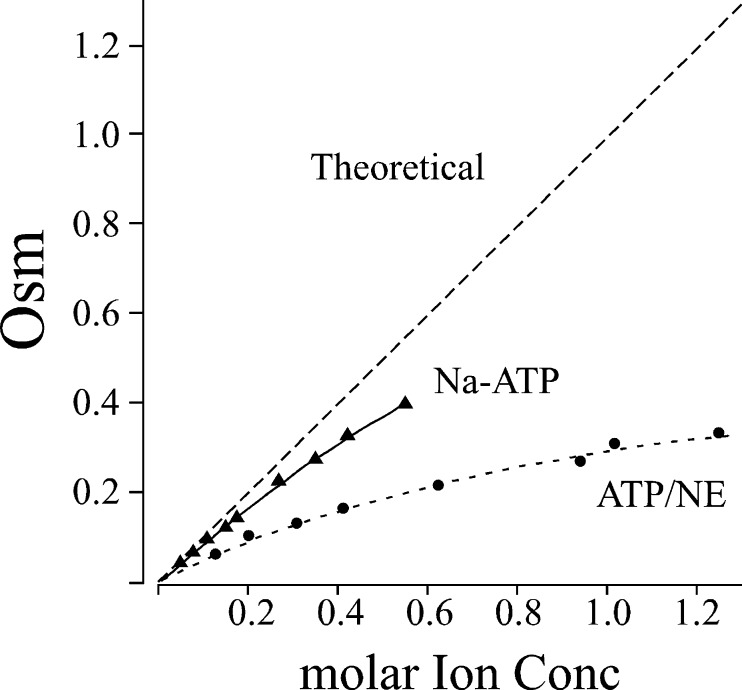

Fig. 1.

ATP behaves as a non-ideal solute for creating osmotic forces. Plots show the osmolarit0y exhibited by Na–ATP and a mixture of ATP: norepinephrine at a proportion 1/2.8. These experiments were conducted by Dr. Edward Westhead using a vapour-phase osmometer during the short visit that he just run to my laboratory

Table 1.

Presence of ATP in secretory vesicles

| Cell type | References |

|---|---|

| Adrenal chromaffin cells | Hillarp et al. (1955) Nature176, 1032–1033; Blaschko et al. (1956) J Physiol133, 548–557.; Carmichael et al. (1980) J Neurochem35, 270–272; Westhead & Winkler (1982) Neuroscience7, 1611–1614. |

| Astrocytes | Cotrina et al. (1998) J Neurosci18, 8794–8804; Guthrie et al. (1999) J Neurosci19, 520–528. |

| Cholinergic nerve skeletal junction | Forrester (1972) J Physiol221, 25P-26P; Luqmani (1981) Neuroscience6, 1011–1021. |

| Cholinergic terminal SNC | Burnstock (1977) Fed Proc36, 2434–2438; Richardson & Brown (1987) J Neurochem48, 622–630. |

| Chondrocytes | Graff et al. (2000) Arthritis Rheum43, 1571–1579. |

| Endothelial cells | Yegutkin et al. (2000) Br J Pharmacol129, 921–926; Bodin & Burnstock (2001) J Cardiovasc Pharmacol38, 900–908. |

| Erythrocytes | Sprague et al. (1998) Am J Physiol275, H1726–1732. |

| Exocrine pancreas | Novak (2003) News Physiol Sci18, 12–17. |

| Fibroblast | Gerasimovskaya et al. (2002) J Biol Chem277, 44638–44650. |

| GABA neurons | Jo & Role (2002) J Neurosci22, 4794–4804. |

| Glutamate neurons | Robertson & Edwards (1998) J Physiol508 (Pt 3), 691–701. |

| HIT cells | Lange & Brandt (1993) FEBS Lett325, 205–209. |

| Lung epithelial | Akopova et al. (2012) Purinergic Signal8, 59–70. |

| Mast cells | Bergendorff & Uvnas (1973) Acta Physiol Scand87, 213–222. |

| Oocytes | Nakamura & Strittmatter (1996) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A93, 10465–10470; Maroto & Hamill (2001) J Biol Chem276, 23867–23872. |

| Osteoblasts | Genetos et al. (2005) J Bone Miner Res20, 41–49; Romanello et al. (2005) Biochem Biophys Res Commun331, 1429–1438; Orriss et al. (2009) J Cell Physiol220, 155–162. |

| PC12 | Wagner (1985) J Neurochem45, 1244–1253. |

| Platelets | Holmsen & Weiss (1979) Annu Rev Med30, 119–134; Luthje & Ogilvie (1983) Biochem Biophys Res Commun115, 253–260. |

| Sympathetic nerves | Burnstock (1988) Trends Pharmacol Sci9, 116–117. |

| Torpedo electric organ | Dowdall et al. (1974) Biochem J140, 1–12; Zimmermann & Denston (1976) Brain Res111, 365–376. |

| β-cells | Hazama et al. (1998) Pflugers Arch437, 31–35. |

As far as I know, all living eukaryotes have vesicles that accumulate ATP. This includes cells as primitive as Giardia lambia, Trychomonas vaginalis, Toxoplasma gondii or Leishmania donovani, microbes involved in several human parasite diseases [4]. In particular, Giardia is a very intriguing microorganism in that it lacks mitochondria and Golgi apparatus but still has dense granules that contain ATP. One can think that these acidic structures were created as a functional ATP reservoir to preserve it from cytosolic degradation in a cell that may not be efficient enough to produce ATP at a high rate. The conjunction of ATP-containing vesicles and constitutive exocytosis was probably the origin of (neuro)secretion in the days when life started. Later simple biochemical modifications on choline, histidine, tryptophan or tyrosine led to cholinergic, histaminergic, serotonergic and sympathetic transmission.

ATP being probably the first neurotransmitter, it seems plausible that the history of secretion started from the fusion of an ATP-contained vesicle with the cell membrane. Newly created transmitters found purinergic vesicles already made. All vesicles accumulate H+: the pH, the electric gradient or both are required for concentrating most transmitters inside. The proton gradient is produced by the V-ATPase, which is also activated by ATP, another fact to think about. Nevertheless, although this commentary will not change any biological fact, we should consider that perhaps exocytosis of ATP is the pillar for understanding cell-to-cell communication.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. E.W. Westhead for his helpful commentaries and to Mr. E. Maristani De Las Casas for his help with some initial experiments. This work was supported by a MICINN (BFU2010-15822), CONSOLIDER (CSD2008-00005) and the Canary Islands' Government C2008/01000239.

References

- 1.Borges R. The rat adrenal gland in the study of the control of catecholamine secretion. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1997;8:113–120. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1996.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borges R, Travis ER, Hochstetler SE, Wightman RM. Effects of external osmotic pressure on vesicular secretion from bovine adrenal medullary cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8325–8331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnstock G. Historical review: ATP as a neurotransmitter. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnstock G, Verkhratsky A. Evolutionary origins of the purinergic signalling system. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;195:415–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz-Vera J, Camacho M, Machado J, Dominguez N, Montesinos M, Hernandez-Fernaud J, Lujan R, Borges R. Chromogranins A and B are key proteins in amine accumulation but the catecholamine secretory pathway is conserved without them. FASEB J. 2012;26(1):430–438. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-181941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopell WN, Westhead EW. Osmotic pressures of solutions of ATP and catecholamines relating to storage in chromaffin granules. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:5707–5710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler H, Westhead E. The molecular organization of adrenal chromaffin granules. Neuroscience. 1980;5:1803–1823. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]