Abstract

Current statistical techniques for analyzing cellular alignment data in the fields of biomaterials and tissue engineering are limited due to heuristic and less quantitative approaches. For example, generally a cut-off degree limit (commonly 20 degrees), is arbitrarily defined within which cells are considered ‘aligned.’ The effectiveness of a patterned biomaterial in guiding the alignment of cells, such as neurons, is often critical to predict relationships between the biomaterial design and biological outcomes, both in vitro and in vivo. This becomes particularly important in the case of peripheral neurons, which require precise axon guidance to obtain successful regenerative outcomes. To address this issue, we have developed a protocol for processing cellular alignment data sets, which implicitly determines an ‘angle of alignment.’ This was accomplished as follows: cells ‘aligning’ with an underlying, anisotropic scaffold display uniformly distributed angles up to a cut-off point determined by how effective the biomaterial is in aligning cells. Therefore, this fact was then used to determine where an alignment angle data set diverges from a uniform distribution. This was accomplished by measuring the spacing between the collected, increasingly ordered angles and analyzing their underlying distributions using a normalized cumulative periodogram (NCP)-criterion. The proposed protocol offers a novel way to implicitly define cellular alignment, with respect to various anisotropic biomaterials. This method may also offer an alternative to assess cellular alignment, which could offer improved predictive measures related to biological outcomes. Further, the approach described can be used for a broad range of cell types grown on 2D surfaces, but would not be applicable to 3D scaffold systems in the present format.

Keywords: Cellular alignment, P19 cells, algorithm, silk

1. Introduction

There currently are no satisfactory treatments for peripheral nerve injury. This is a critical clinical issue, as approximately 2.8% of trauma cases present with this type of injury1. The gold standard in the field of microsurgery is the autologous nerve graft, which reconnects the nerve cable fascicles for realignment to the proper target outputs, while minimizing mechanical strain on the nerve. However, this surgical procedure is plagued by numerous issues, including a shortage of donor nerves, donor site morbidity, nerve site mismatch, and the formation of neuroma2,3. While microsurgical procedures, such as the nerve graft, involve the suturing of nerve fascicles, a tissue engineering approach can exploit cellular processes4, with successful approaches expected to incorporate a combination of growth factor delivery, adhesive proteins, and physical cues, all delivered in an anisotropic fashion.

Biomaterial scaffold anisotropy is essential for nerve regeneration applications as it yields controlled re-wiring of axons to their original functional outputs. Indeed, superior cellular alignment has been shown to significantly influence in vivo regenerative outcomes5,6,7 and encourage synaptogenesis8. Thus, to judge the efficacy of biomaterial scaffolds in aligning neural cell types, it is essential to assess directional neurite outgrowth. Cellular alignment has been assessed using manual methods9, as well as semi-automated and automated algorithms10,11,12,13, to identify cellular orientation in complex environments. Traditionally in neural tissue engineering, alignment has been defined by obtaining the angle deviation of a cell’s longest neurite off of the ‘axis of alignment’ (the direction of the stimulus); then, alignment is heuristically defined, as the percentage of neural cells (Schwann and/or nerve cells) contained within +/− n degrees, with n usually being 10 or 2014,15,16,17. These metrics for judging cellular orientation have been improved through use of circular analysis18; however, the statistical method is still not able to quantitatively define a range of alignment. The angle of alignment is a feature of the anisotropic scaffold on which cells are plated; therefore, that angle needs to be determined.

The current study describes the development of a simple algorithm for implicitly determining cellular alignment efficacy, with respect to flat and patterned biomaterial films. While the prototype study was based on nerve cells, the implications are that the technique could be used for almost any cell type growing on a surface.

When cells ‘align’, they are uniformly distributing themselves throughout a narrow angle set, with a mean that clusters around 0 degrees of deviation from the axis of alignment. The range of angles over which the cells are uniformly distributed determines the efficacy of a given scaffold in aligning different cell types. In the present work, we use a mouse embryonal teratocarcinoma cell line, neuronally-differentiated P19 cells, to evaluate cellular alignment on different flat and micropatterned silk protein biomaterial films. Using the cellular alignment data, we implicitly define a cut-off beyond which cells can no longer be considered to be aligned with the films. In the case of a flat film, there is no directional stimulus, so the angles will be uniformly distributed over a 90 degree range. Thus, the narrower the range of angles over which the cells align the more effective a given scaffold is at guiding directional neurite outgrowth.

To quantitatively evaluate when a cell diverges from ‘aligned’ angle set, we developed a protocol, which employs the normalized cumulative periodogram (NCP) to define when an angle set strays form the uniform distribution19. This NCP-criterion is applied to a processed form of the angle data set, by measuring the spacing between the collected, increasingly ordered alignment angles from the various films. The current approach is a novel way to quantitatively and implicitly evaluate cellular alignment. This technique also allows comparisons among different biomaterials towards obtaining optimized cellular alignment.

2. Methods

2.1 Preparation of silk fibroin solution

An 8% (w/v) aqueous silk fibroin solution was prepared from the cocoons of the B. mori silkworm using our previous procedures20,21. Briefly, cocoons were boiled for 30 minutes before being extracted using a 0.02 M Na2CO3 solution and rinsed in distilled water. The silk was then dissolved in a 9.3 M LiBr solution, and dialyzed against 1 L of Milli-Q. For purity, the silk was centrifuged at ~9,000 rpm for 20 minutes, at 5-10°C.

2.2 Preparation of silk films

Flat and micropatterned silk films for the alignment of the P19 cells were prepared according to our previously established protocols22. Briefly, silk solutions were cast onto polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) molds obtained from diffraction gratings of dimensions 300-8 and 300-17 (Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ) and allowed to dry overnight. The films were then water-annealed for 7 hours to induce a transition from the amorphous aqueous phase to the anti-parallel β-sheets23. The films were sterilized with 3 alternating ethanol washes (lasting 20 minutes) and PBS washes, followed by 20 minutes of UV irradiation. Prior to cell plating, all films were coated with laminin by adsorption of a 25 μg/mL natural mouse laminin solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 2 hours at 37°C, before being carefully rinsed 3 times with PBS.

2.3 Cell culture

Mouse embryonal teratocarcinoma (P19) cells were cultured according to manufacturer protocol (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Briefly, the P19 cells were cultured in α-Minimum Essential Medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), 2.5% Fetal Bovine Serum (Invitrogen), and 7.5% bovine calf serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2/95% air. Media was replenished every 3 days, and cells were passaged at 60-70% confluence using trypsin (0.25% with EDTA 4Na, Invitrogen). Cells were frozen using cryogenic medium (90% bovine calf serum, 10% DMSO).

2.4 Cell differentiation

The P19 cells were differentiated down a neuronal lineage over 5 days24,25,26. Briefly, on day 1, ~1×106 cells were manually dissociated with a flared-tip Pasteur pipette and plated onto bacteriological culture dishes, followed by exposure to 0.1 μM retinoic acid (RA). On culture days 3 and 4, the same process was repeated, with one exception. The cells were treated with trypsin prior to manual dissociation to eliminate potential focal adhesion proteins. On day 4, the cells were plated and on day 5 the cells were treated with 5 μg/mL cytosine arabinoside (araC) to kill remaining proliferating cells.

2.5 Quantification of P19 Cell Alignment and Neurite Outgrowth

A MATLAB program was developed to measure the angle of neurites off of the axis of alignment. For flat films, the axis was arbitrarily chosen to be the horizontal axis. This was accomplished through generating an axis vector (a) and a neurite vector (b). The angle of orientation (θ) was then obtained using the Law of Cosines: Law of Cosines, transformed: θ = cos−1(∣a · b∣/∣a∣∣b∣)

2.6 Imaging

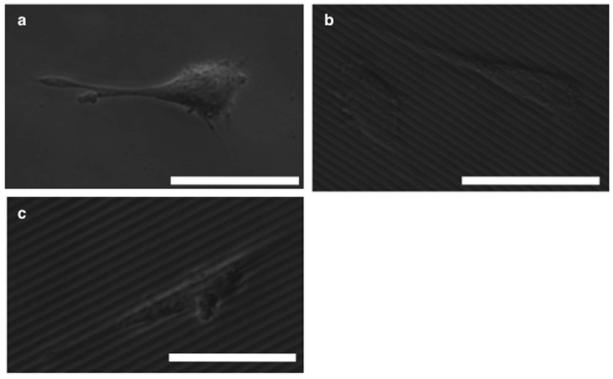

Prior to cell plating, flat and micropatterned silk films were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with an InLens detector (Zeiss, Supra55VP). Prior to imaging, the films were coated with platinum/palladium. Live imaging of the P19 neurons on the flat (Figure 1a) and micropatterned films (Figure 1b-c) was performed using phase contrast microscopy (DM IL, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL). The longest neurite on each P19 neuron was used for cellular alignment analysis described in the previous section (Section 2.5).

Figure 1.

Phase contrast micrographs of P19 neurons on flat and micropatterned silk films. Micrographs displaying cells on flat (a) and aligned 300-8 (b) and 300-17 (c) silk films. Scale bar, 25 μm.

2.7 Data Analysis

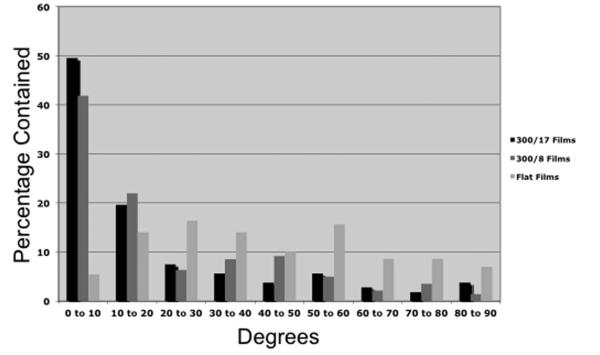

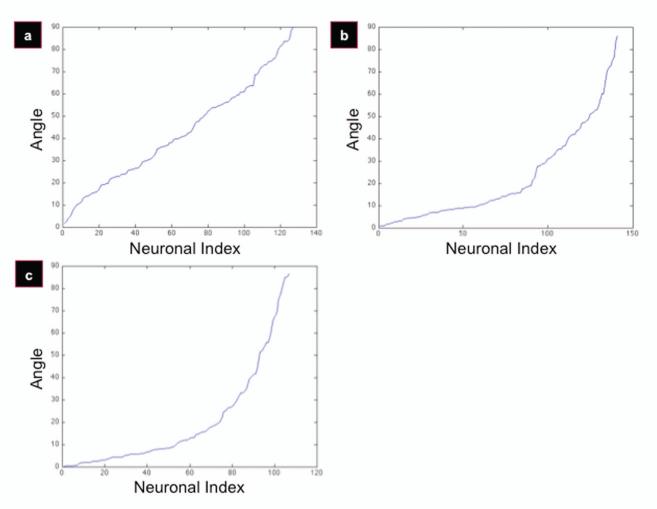

When cells align to an anisotropic scaffold, the angle outputs are uniformly distributed up to a certain threshold, beyond which the cells can no longer be considered to be ‘aligned’ with that scaffold. This is for two reasons. First, plots are created with increasing angle outputs as a function of neuronal index (the neuron number). When cells are plated onto flat films, the angle outputs are uniformly distributed over all of the angle bins, ranging from 0 to 90 degrees (Figure 2, Flat Films). This presents as a semi-linear trend in the angle-index plots, as in Figure 3a. Second, when the cells are plated onto patterned films, there is a semi-linear trend for only initial portions of the patterned film plots (Figure 3b,c). The angle up to which the initial segment remains uniformly distributed will be used to determine the efficacy of a scaffold in aligning cells. The plot with the narrowest angle set under a uniform distribution, therefore, represents the most effective scaffold to obtain cellular alignment.

Figure 2.

Histogram of P19 cells on flat and micropatterned silk fibroin films. Alignment angles of individual neurons were obtained by hand-drawn vectors, and the angles were then binned in 10-degree increments.

Figure 3.

Angle distribution plots. Regressions display sorted (increasing) angles, plotted as a function of neuronal index. Pseudo-linear trends are indicative of a uniform random distribution. Plots display flat (a), 300/8 (b), and 300/17 (c) silk films.

To perform this portion of the data analysis, we sorted the set of alignment angles in increasing order (as described above). At some point, the set reached a uniform distribution; if too many angles were then added to this set, the set was no longer uniformly distributed. Therefore, the angle for which that uniformity disappears needed to be obtained. To determine this angle, we used an algorithm based on the normalized cumulative periodogram19, called the NCP-criterion.

The normalized cumulative periodogram (NCP)-criterion is useful for determining when a signal strays from the uniform distribution. The NCP-criterion is a technique based on the discrete Fourier transform (DFT), which analyzes the underlying distribution of a generalized n-length vector signal. Briefly, the power spectrum of the signal’s frequencies from 1 to k is evaluated, and normalized over the length (n) of the signal, at each iteration. Thus, the kth element of the NCP vector is equivalent to taking a normalized integral of the power spectrum over frequencies 1 to k19. The statistical limits of the NCP vector are set at a 0.05 significance level, using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The NCP of a white noise signal should appear linear and fall within the statistical boundaries. Additionally, an algorithm developed by Hansen et al contains a Boolean metric based on the NCP, which is able to determine whether or not the input signal is within the statistical limits.

In the case of managing cellular alignment data, the n-length vector was comprised of the local differences between angles of the sorted data observed in Figure 3, and n was the sample size. Briefly, to obtain an ‘angle difference’ for the k+1th index, the kth angle was subtracted from the k+1st angle. This was the data set to which we applied the NCP-criterion. The justification for using angle differences and not the angles, themselves, was two-fold. First, the local differences of a uniformly distributed data set are also uniformly distributed around the same mean and median. Second, analyzing the differences between angles can much more sensitively detect divergence from the uniform distribution, so this is a much more effective metric.

To determine the angle of alignment in a given data set, the NCP-criterion was run on the angles in 5-cell increments. The neuronal index at which a given NCP breached the Kolmogorov-Smirnov limits, determined by the Boolean metric described above, was used to determine the angle beyond which neurons could no longer be considered to be ‘aligned.’ The angle corresponding to the neuronal index at which the NCP strayed from the uniform distribution was determined as the ‘angle of alignment.’ To obtain the corresponding angle, we interpolated from the neuronal index in Figure 3.

3. Results

3.1 Alignment of P19 Neurons on Silk Films

The P19 neurons were plated onto laminin-coated flat and micropatterned silk films and analyzed using phase contrast microscopy (Figure 1). Alignment of the cells on the various films was assessed using a brief MATLAB program, using the transformed Law of Cosines. The best alignment was found using the 300-17 films (1 groove per 3.33 μm, 17° angle pitch), followed by the 300-8 films (1 groove per 3.33 μm, 8° angle pitch), and then the flat films, as observed in Figure 2. For the 300-17 films, ~50% of the cells aligned within 10 degrees (and ~69% within 20 degrees), compared to ~42% within 10 degrees (and ~64% within 20 degrees) for the 300-8 films (see Figure 2 for alignment histogram). The neurons on the flat silk films had neurites uniformly distributed throughout all of the angle bins.

3.2 Qualitative Assessment of Scaffold Influence

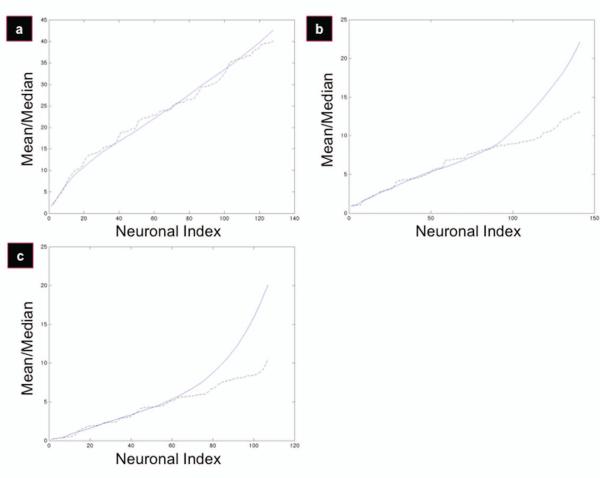

Figure 3 displays plots of increasing angles as a function of neuronal index. As previously mentioned, semi-linear trends correspond to underlying uniform distributions in the data set. To first qualitatively identify the data sets that diverge from the uniform distribution at some point, we plotted the mean-median divergence, calculated as a function of increasing neuronal index. In a uniform distribution, the mean and the median are equivalent; so when the mean and median finally diverge, the underlying distribution is no longer uniform. The flat films had no divergence (Figure 4a), whereas the patterned films had clear divergence (Figure 4b,c). Thus, the patterned films were successful in aligning the P19 cells to some degree, and the flat films were not.

Figure 4.

Diagrams displaying mean-median divergence for flat (a), 300/8 (b), and 300/17 (c) films. Mean and median were calculated as a function of increasing neuronal index. The divergence point between the two different regressions is considered the point beyond which cells are no longer considered ‘aligning’ to the underlying scaffold. Mean is a solid blue line; median is a dashed black line.

3.3 Determining the Angle of Alignment

While it is intuitively obvious that the 300-17 films were more successful in aligning the P19 cells as compared to the 300-8 films (because a higher percentage of cells were in the narrower angle sets), there exists no satisfactory, quantitative metric to corroborate this observation. Thus, angle spacing analysis was performed, as described above, to determine each scaffold’s alignment efficacy. As discussed in Section 3.2, the flat films were found to have uniformly distributed angles over the range of angles (from 0 to 90 degrees). Thus, there is no divergence point from the uniform distribution, and the flat films exert no influence over directional cellular alignment. However, the patterned films were found to have a mean-median divergence, which remains to be determined. Angle spacing distributions were obtained for the flat (Figure 5a) and the patterned films (Figure 5b,c), and the NCP-criterion was applied to each of these data sets.

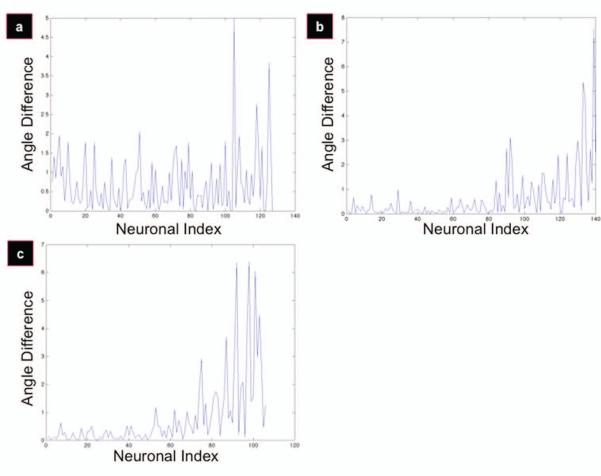

Figure 5.

Angle spacing distribution. Plots display the local angle differential of sorted angles from Figure 2 for flat (a), 300/8 (b), and 300/17 (c) films. To obtain an ‘angle difference’ for the k+1th neuron, the kth angle was subtracted from the k+1st angle. This is the data set to which the NCP-criterion is successfully applied.

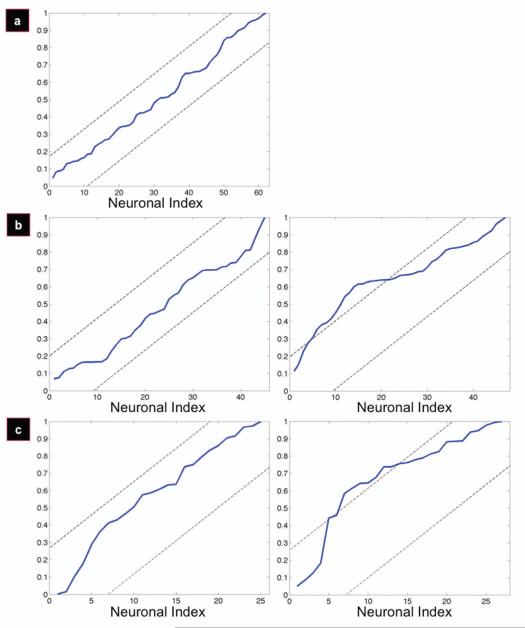

The point at which the angle sets diverged from the uniform distribution was quantitatively defined where the normalized cumulative periodogram breached the boundaries set by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test at a 0.05 significance level (the limits at 0.05 are +/− 1.36*q, where q = (n/2) + 1). While the flat films had no divergence from the uniform distribution (Figure 6a), this corresponded to the 90th (of 141) cells for the 300-8 films (Figure 6b) and the 50th (of 107) cells for the 300-17 films (Figure 6c). Interpolating from neuronal index to angle using the plots seen in Figure 3, the 90th angle of the 300-8 films corresponded to an angle of ~19 degrees, and the 50th angle of the 300-17 films corresponded to an angle of ~8 degrees. Thus, the angle of alignment for the 300-17 films is 8 degrees, and the angle of alignment for the 300-8 films is 19 degrees. Therefore, the 300-17 films are more effective in aligning P19 cells than the 300-8 films.

Figure 6.

Normalized cumulative periodograms (NCPs) displaying the uniform (left panel) angle sets where the underlying distributions become non-uniform (right panel). The dashed lines are limits obtained using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test at a 0.05 significance level.

4. Discussion

To date, regenerative outcomes in peripheral nerve tissue engineering have been less than satisfactory2. Despite numerous advances in the field, functional outcomes can be inhibited by imprecise distal targeting of the regenerating axons27, leading to poor axonal connections and thus loss of restoration of function. Thus, there is a need for improved biophysical approaches to aligning neurons and assessing cellular alignment in a quantitative manner. However, there are currently no satisfactory quantitative measures for implicitly defining cellular alignment. While there are many excellent automated algorithms for quantitatively measuring cellular deviation from a given axis of alignment10,11,12,13, the current measurements defining alignment are heuristic, often arbitrarily designating a +/− 10 or 20 degree benchmark as ‘aligned’14,15,16,17. A recent study has greatly improved the quantitative assessment of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) directional neurite outgrowth using circular analysis18, though this work still does not offer a quantitative angle value beyond which cells can no longer be considered ‘aligned.’ Thus, a quantitative measure, which can aptly define an angle of alignment would be very beneficial to the field of neural tissue engineering.

We have shown that cellular alignment data can be quantitatively analyzed by investigating the properties of their underlying statistical distributions. P19 cells were plated onto flat and micropatterned silk fibroin films, and their alignment was quantitatively assessed. The current work demonstrates that when cells align with an anisotropic patterned scaffold, they ‘align’ up to a certain angle value and uniformly distribute their neurite angles over the aligned angle range. Because of this observation, we are able to analyze cellular alignment with algorithms that can identify uniformly distributed data sets. Under the random uniform distribution, the mean and median are equivalent; thus, when the mean and the median diverge, the data set is no longer uniform. To identify the point at which the data set diverges from uniformity, we measured the spacing between the measured neurite angles off of the axis of alignment. It is possible to understand trends in the original angle data set by measuring angle spacing because of a property of the discrete uniform distribution: the spacing between a uniformly distributed data set is also, itself, uniformly distributed.

Thus, to assess when the trend of uniformity disappeared, we used a normalized cumulative periodogram (NCP)-criterion, previously developed by one of the current authors19. The NCP-criterion is based on the discrete Fourier transform, and it can quantitatively assess when a distribution strays from uniformity. By obtaining the divergence point from uniformity over the three data sets (flat, 300-8, and 300-17 films), we were able to define an ‘angle of alignment’ and conclude that the 300-17 films were the most effective in aligning the P19 cells on silk. Additionally, this technique can be applied generally to alignment data for any cell types with polarized morphologies.

5. Conclusions

The current work presents a quantitative metric for both defining cellular alignment and comparing alignment outcomes on various biomaterial formats. Nerve cell alignment has been shown to significantly enhance regenerative outcomes in vivo5,6; therefore, it will be important to begin correlating regenerative outcomes as a function of in vitro cellular alignment. This work offers a method for quantitatively evaluating these in vitro cellular alignment outcomes. The applicability of the methods presented in this work would permeate many different areas of study involving cell alignment on surfaces, in response to external stimuli and related studies. The method at present is limited to 2D systems and it would be useful to extend the approach presented here into 3D for broader relevance to many areas of need in regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Biman Mandal for contributing micropatterned silk films. We thank the Tissue Engineering Resource Center (TERC) through the NIH (P41EB002520) from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine (AFIRM) for support for this work.

Contributor Information

Alexander R. Nectow, Telephone: (339) 225-0315 Fax: (617) 627-3231 Alexander.Nectow@Tufts.edu.

Eun Seok Gil, Telephone: (617) 627-2580 Fax: (617) 627-3231 Eun.Gil@Tufts.edu.

David L. Kaplan, Telephone: (617) 627-2580 Fax: (617) 627-3231 David.Kaplan@Tufts.edu.

References

- 1.Noble J, Munro CA, Prasad VSSV, Midha R. Analysis of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve injuries in a population of patients with multiple injuries. J Trauma. 1998;45:116–122. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellamkonda RV. Peripheral nerve regeneration: An opinion on channels, scaffolds and anisotropy. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3515–3518. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YC, Huang YY. Biomaterials and strategies for nerve regeneration. Artificial Organs. 2006;30:514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2006.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson TW, Evans GR, Schmidt CE. Engineering strategies for peripheral nerve repair. Clin Plast Surg. 1999;26:617–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clements IP, Kim YT, English AW, Lu X, Chung A, Bellamkonda RV. Thin-film enhanced nerve guidance channels for peripheral nerve repair. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3834–3846. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YT, Haftel VK, Kumar S, Bellamkonda RV. The role of aligned polymer fiber-based constructs in the bridging of long peripheral nerve gaps. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3117–3127. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nectow AR, Marra KG, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials for the development of nerve guidance conduits. Tissue Engineering Part B Reviews. 2012;18:40–50. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cecchini M, Bumma G, Serresi M, Beltram F. PC12 differentiation on biopolymer nanostructures. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahoney MJ, Chen RR, Tan J, Saltzman WM. The influence of microchannels on neurite growth and architecture. Biomaterials. 2005;26:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray MAP, Adams WJ, Geisse NA, Feinberg AW, Sheehy SP, Parker KK. Nuclear morphology and deformation in engineered cardiac myocytes and tissues. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5143–5150. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haines C, Goodhill GJ. Analyzing neurite outgrowth from explants by fitting ellipses. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2010;187:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlon WJ, Hsu PP, Li S, Chien S, McCulloch AD, Omens JH. Measurement of orientation and distribution of cellular alignment and cytoskeletal organization. Ann Biomed Eng. 1999;27:712–720. doi: 10.1114/1.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu F, Beyazoglu T, Hefner E, Gurkan UA, Demirci U. Automated and adaptable quantification of cellular alignment from microscopic images for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Engineering Part C Methods. 2011;17:641–649. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin J, Delgado-Rivera R, Meiners S, Uhrich KE. Salicylic acid-derived poly(anhydride-ester) electrospun fibers designed for regenerating the peripheral nervous system. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;97:230–242. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmalenberg KE, Uhrich KE. Micropatterned polymer substrates control alignment of proliferating Schwann cells to direct neuronal regeneration. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1423–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun M, McGowan M, Kingham PJ, Terenghi G, Downes S. Novel thin-walled nerve conduit with microgrooved surface patterns for enhanced peripheral nerve repair. J. Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21:2765–2774. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tai HC, Buettner HM. Neurite outgrowth and growth cone morphology on micropatterned surfaces. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:364–370. doi: 10.1021/bp980035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li GN, Hoffman-Kim D. Tissue-engineered platforms of axon guidance. Tissue Engineering: Part B. 2008;14:33–51. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen PC, Kilmer ME, Kjeldsen RH. Exploiting residual information in the parameter choice for discrete ill-posed problems. BIT Numerical Mathematics. 2006;46:41–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim UJ, Park J, Li C, Jin HJ, Valluzzi R, Kaplan DL. Structure and properties of silk hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:786–792. doi: 10.1021/bm0345460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C, Vepari C, Jin HJ, Kim HJ, Kaplan DL. Electrospun silk-BMP-2 scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3115–3124. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence BD, Cronin-Golomb M, Georgakoudi I, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG. Bioactive silk protein biomaterial systems for optical devices. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1214–1220. doi: 10.1021/bm701235f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin HJ, Kaplan DL. Mechanism of silk processing in insects and spiders. Nature. 2003;424:1057–1061. doi: 10.1038/nature01809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones-Villeneuve EMV, McBurney MW, Rogers KA, Kalnins VI. Retinoic acid induces embryonal carcinoma cells to differentiate into neurons and glial cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1982;94:253–262. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones-Villeneuve EMV, Rudnicki MA, Harris JF, McBurney MW. Retinoic acid-induced neural differentiation of embryonal carcinoma cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1983;3:2271–2279. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.12.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McBurney MW, Reuhl KR, Ally AI, Nasipuri S, Bell JC, Craig J. Differentiation and maturation of embryonal carcinoma-derived neurons in cell culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:1063–1073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-01063.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belkas JS, Shoichet MS, Midha R. Peripheral nerve regeneration through guidance tubes. Neurological Research. 2004;26:151–160. doi: 10.1179/016164104225013798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]