Abstract

BK virus-allograft nephropathy (BKVAN) is an increasingly recognized complication after kidney transplantation. Quantitative tests have been advocated to monitor patients, but data demonstrating their efficacy are relatively limited. We developed a real-time PCR assay to quantitate BK virus loads in the setting of renal transplantation, and we correlated the BK virus load with clinical course and with the presence of BK virus in renal biopsy specimens. BK virus loads were measured in urine, plasma, and kidney biopsy samples in three clinical settings: (i) patients with asymptomatic BK viruria, (ii) patients with active BKVAN, and (iii) patients with resolved BKVAN. Active BKVAN was associated with BK viremia greater than 5 × 103 copies/ml and with BK viruria greater than 107 copies/ml in all cases. Resolution of nephropathy led to resolution of viremia, decreased viruria levels, and disappearance of viral inclusions, but low-level viral DNA persisted in biopsy specimens even for patients whose viruria was cleared. All but one patient in the resolved BKVAN group carried a urinary viral load below 107 copies/ml. Viral loads in patients with asymptomatic viruria were generally lower but in some cases overlapped with levels more typical of BKVAN. One patient with asymptomatic viruria and with a viral load overlapping values seen in BKVAN had developed nephropathy by the time of follow-up. In conclusion, serial measurement of viral loads by quantitative PCR is a useful tool in monitoring the course of BK virus infection. The results should be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical picture and biopsy findings.

The introduction of potent immunosuppressive drugs in the past decade has led to the emergence of the BK virus (BKV) nephropathy syndrome in as many as 8% of kidney transplant recipients (2, 4, 7, 8). This syndrome is characterized by persistent graft dysfunction and frequent graft loss. The mainstay of therapy is reduction of immunosuppression to allow the host to mount a successful antiviral immune response. Treatment with low-dose cidofovir has apparently been useful in a number of cases reported, but no controlled trials have been performed (1, 3, 10, 11). Once therapy has been initiated, quantitative testing for BKV loads has been suggested as a way to monitor the clinical course of infection (5, 6, 9, 11). Relatively limited data are available on how the BKV load correlates with specific phases of disease, namely, active viral nephropathy, histologic resolution, and subclinical viruria. We measured BKV loads in plasma, urine, and tissue samples obtained from well-defined categories of patients after renal transplantation, and we demonstrate how the results of such testing can be interpreted in the appropriate clinical context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples were taken from adult patients undergoing renal transplantation after informed consent was obtained. Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes, and the plasma fraction was separated out by low-speed centrifugation. Urine was collected as random midstream samples in sterile cups and was used without centrifugation. Samples were frozen at −80°C within 6 h and assayed within 7 days. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol 000586-0106).

DNA was extracted with the QIAamp Blood maxikit (catalog no. 51192; Qiagen) for urine or the QIAamp Blood minikit (catalog no. 51104; Qiagen) for plasma by using 5 ml of uncentrifuged urine or 200 μl of plasma. The final extraction volumes were 200 and 40 μl, respectively. The following oligonucleotide sequences, derived from the BKV (Dunlop strain; GenBank accession no. NC001538) capsid protein-1 (VP-1) gene, were synthesized (IT BioChem, Salt Lake City, Utah): forward primer, 5′ GCA GCT CCC AAA AAG CCA AA 3′; reverse primer, 5′ CTG GGT TTAGGA AGC ATT CTA 3′.

The sequences were checked for homology by a BLAST search performed on a website maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the National Library of Medicine (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Specificity for BKV DNA was confirmed by using a plasmid containing full-length BKV, JC virus, or simian virus 40 (SV40) genomic DNA (catalog no. 45025, 45027, or 45019, respectively; American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, Va.).

Quantitative real-time PCR assays were performed using the Roche LightCycler. PCR amplifications were run in a reaction volume of 20 μl containing 2 μl of the DNA sample, Roche 10× SybrGreen FasStart mastermix, 2.5 mM magnesium chloride, and 500 nM (each) forward and reverse primers. Thermal cycling was initiated with a first denaturation step of 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 62°C for 10 s, 72°C for 5 s, and 78°C for 10 s, at the end of which fluorescence was read. Real-time PCR amplification data were analyzed with software provided by the manufacturer. Standard curves for the quantification of BKV were constructed using serial dilutions of a plasmid containing the entire linearized genome of the BKV Dun strain inserted into the BamHI restriction site of the pBR322 plasmid (ATCC 45025). The plasmid concentrations plotted ranged from 1 to 1011 genomic copies of BKV DNA per PCR. All patient samples were tested in duplicate, and the number of BKV copies was calculated from the standard curve. Data were expressed as copies of viral DNA per milliliter of urine or plasma, or per cell in the biopsy samples. Standard precautions designed to prevent contamination during PCR were followed. No-template control lanes and negative-control samples (DNA extracted from human peripheral blood lymphocytes) were included in each run.

Renal allograft biopsy specimens from these patients were subjected to routine formalin fixation and paraffin embedding. Viral DNA was demonstrated in the infected cells by using in situ hybridization with a commercially available probe (Enzo Diagnostics, Farmingdale, N.Y.). In 32 biopsy specimens, sufficient tissue was available to quantitate intrarenal concentrations of BKV DNA by real-time PCR, as previously published (9). Viral copy numbers were expressed on a per-cell basis after simultaneous amplification of the house keeping enzyme asparto-acylase. Pertinent clinical information was obtained by review of the medical records.

RESULTS

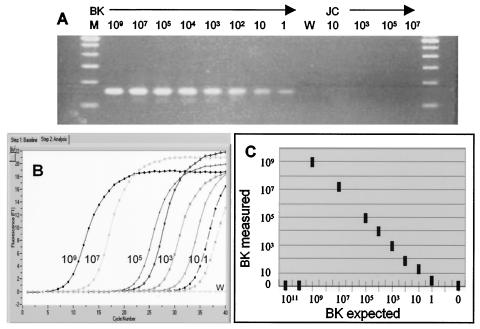

We developed and evaluated a real-time PCR method for quantitating BKV which can differentiate between BKV and the related human polyomaviruses JC virus and SV40. This method takes advantage of a 24-bp deletion in the VP-1 gene of JC virus compared to that of BKV. The forward PCR primer has no cross-reactivity with JC virus, since the homologous region is deleted in JC virus. The reverse primer has 80% sequence homology with JCV and <70% sequence homology with SV40. The specificity of the primers for BKV was tested by using plasmids containing full-length BKV, SV40, or JC virus genomic DNA. The BKV control plasmid could be detected in a quantitative fashion, and no amplification of the JC virus control plasmid (up to 107 copies) was seen (Fig. 1A). Similarly, no amplification product was detected for an SV40 control plasmid used at a concentration of 106 copies/ml (data not shown). The SybrGreen real-time PCR format described here monitors the increase in the double-stranded DNA PCR product at each cycle (Fig. 1B). Postamplification melting-curve analysis is used to distinguish between BKV and nonspecific PCR products. BKV PCR products have a melting temperature (Tm) of 81°C (data not shown). The assay demonstrated a wide linear range from 10 to 109 copy equivalents of viral DNA and could detect as little as 1 copy equivalent of BKV DNA (Fig. 1B and C). This corresponds to a linear range of 2 × 102 to 2 × 1010 copies/ml of urine and 103 to 1011 copies/ml of plasma. The assay linearity dropped off above 109 copies of viral DNA because background template fluorescence was so high that the LightCycler software could not calculate a value (Fig. 1C). The average interrun coefficient of variation was 28.2%, and the average intrarun coefficient of variation was 24.7%. Reextraction from 17 plasma and urine samples generally yielded less than threefold variation (one sample differed fivefold). The assay detected BKV excretion in 19% of patients in the kidney transplant program at the University of Pittsburgh.

FIG. 1.

Characteristics of the BKV real-time PCR assay. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products generated by using BKV-specific primers and BKV or JC virus plasmid controls. Rightmost and leftmost lanes, DNA size markers; lane W, water blank; 2nd to 9th lanes, 10-fold serial dilutions of BKV plasmid DNA from 109 copies to 1 copy; 11th to 14th lanes, JC virus plasmid DNA from 10 to 107 copies. (B) Quantitative PCR assay of the same BKV standards with SybrGreen detection. (C) Linear range of the assay obtained by use of known serial dilutions of the BKV plasmid as a template. Shown is the BKV copy number calculated from the standard curve (BK measured) versus the known BKV copy equivalents put into the PCR as unknowns (BK expected). Each data point is an average from 3 to 10 separate experiments. At viral copy numbers of >109, the background template fluorescence becomes significant and linearity fails.

We analyzed BKV loads in urine, plasma, and biopsy samples obtained from patients with asymptomatic viruria and active or resolved BKV allograft nephropathy (BKVAN). The diagnosis of active viral nephropathy in each case was based on standard histopathologic examination. Light microscopy showed viral inclusions in the tubular epithelium, accompanied by variable interstitial inflammation (8). Viral DNA was demonstrated in the infected cells by use of in situ hybridization. Following reduction of immunosuppression, in situ hybridization could no longer detect viral DNA in the biopsy tissues of several patients. This group of patients was considered to represent resolved nephropathy. Clinical samples were assigned to four groups as follows.

(i) The negative-control group consisted of 76 urine and 76 plasma samples obtained from 51 patients with no evidence of BKVAN and negative PCR for viral DNA.

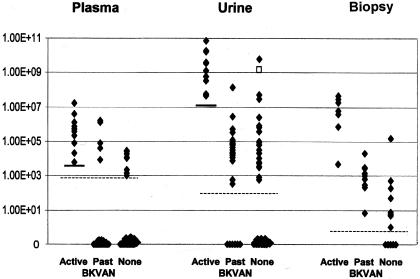

(ii) The asymptomatic BK viruria group consisted of 33 urine, 33 plasma, and 10 biopsy samples obtained from 15 patients (Table 1; Fig. 2). The median viral load in the urine was 6.02E+03 copies/ml (range, 0.00E+00 to 5.86E+09 copies/ml). No virus was generally detected in the plasma of these patients (median, zero). However, eight samples from five patients showed circulating BKV DNA levels ranging from 1.07E+03 to 2.90E+04 copies/ml, even though the allograft biopsies showed no viral nephropathy. One of these patients showed a rise in the serum creatinine level and was presumptively treated for viral nephropathy by reduction of immunosuppression. It is possible that the lack of demonstrable viral inclusions in the biopsy specimen was the result of sampling error. One patient who presented with asymptomatic viruria went on to develop biopsy-proven viral nephropathy. Quantitative PCRs on biopsy tissue generally showed no viral DNA or less than 1 copy per cell, except for a single sample which yielded 152 copies per cell. This was a consultation case for which no further follow-up is available.

TABLE 1.

Correlation of BKV loads in urine, plasma, and biopsy samples with clinical status

| Type of sample | Viral loada for the following clinical status:

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic viruria

|

Resolved BKVAN

|

Active BKVAN

|

|||||||||||||

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Median | No. of cases | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Median | No. of cases | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Median | No. of cases | |

| Urine | 0.00E + 00 | 5.86E + 09 | 2.25E + 08 | 6.02E + 03 | 33 | 0.00E + 00 | 1.38E + 08 | 5.28E + 06 | 2.24E + 04 | 27 | 4.68E + 07 | 7.26E + 10 | 1.18E + 10 | 2.38E + 09 | 10 |

| Plasma | 0.00E + 00 | 2.90E + 04 | 3.02E + 03 | 0.00E + 00 | 33 | 0.00E + 00 | 1.58E + 06 | 9.43E + 04 | 0.00E + 00 | 32 | 6.22E + 03 | 1.64E + 07 | 2.35E + 06 | 4.43E + 05 | 10 |

| Renal biopsy | 0.00E + 00 | 1.52E + 02 | 1.09E + 01 | 5.21E − 03 | 10 | 2.13E − 01 | 2.16E + 01 | 3.91E + 00 | 1.24E + 00 | 9 | 2.88E + 00 | 4.37E + 04 | 1.07E + 04 | 3.95E + 04 | 11 |

Expressed in copies per milliliter for urine and plasma samples and in copies per cell for renal biopsy samples.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of BKV loads in renal transplant patient groups. Data are expressed as log viral copies per milliliter (for plasma and urine samples) or per 1,000 cells (for biopsy specimens). Data in the no BKVAN group (None) include samples from patients with asymptomatic viruria as well as from negative controls with no evidence of BKVAN. Dashed lines indicate the limit of detection in the various sample types. The open square represents a patient who subsequently developed BKVAN. Solid bars indicate the suggested viral load cutoffs useful for diagnosis of BKVAN. A cutoff of 1.00E+07 copies of BKV/ml in urine had a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 96%, a negative predictive value of 100%, and a positive predictive value of 67% for BKVAN. A cutoff of 5.00E+03 copies of BKV/ml in plasma had a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 93%, a negative predictive value of 100%, and a positive predictive value of 50% for BKVAN. A Mann-Whitney test indicated that viral loads in the active BKVAN group were significantly higher than those in the resolved BKVAN group (P < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between viral loads in the resolved BKVAN group and those in the asymptomatic viruria (“None”) group.

(iii) The active BKVAN group consisted of 10 urine, 10 plasma, and 11 biopsy samples obtained from eight patients. Seven samples had been obtained within 5 days of a histologic diagnosis of BKVAN. The remaining samples were taken as many as 61 days following the initial diagnosis, but a follow-up biopsy confirmed the presence of ongoing nephropathy, with virus-associated parenchymal injury to the allograft kidney. The urine samples in this group showed a median viral load of 2.38E+09 copies/ml (range, 4.68E+07 to 7.26E+10 copies/ml). Plasma viremia was detected in all patients, with a median viral load of 4.43E+05 copies/ml (range, 6.22E+03 to 1.64E+07 copies/ml). The median intrarenal viral concentration was 3.95E+04 copies/cell (range, 2.88E+0 to 4.37E+04 copies/cell).

(iv) The resolved BKVAN group consisted of 32 plasma, 27 urine, and 9 biopsy samples from 10 patients who had a previous diagnosis of BKVAN. Thirteen samples had been obtained within 3 days of a biopsy confirming the absence of active viral nephropathy. The remaining samples were spaced farther out from the index biopsy, but a follow-up biopsy confirmed the absence of active nephropathy during the interval of observation. Hence, these samples were also assigned to the resolved BKVAN group. The urine samples in this group showed a median viral load of 2.24E+04 copies/ml (range, 0.00E+00 to 1.38E+08 copies/ml). There was usually no viremia in these patients (median plasma viral load, zero). However, four patients showed circulating viral DNA levels varying from 8.26E+03 to 1.58E+06 copies/ml. It appears that viral clearance from the blood lagged behind viral clearance from the allograft kidney in these individuals. Quantitative PCR performed on biopsy tissue in this group of patients demonstrated a median viral load of 1.24 copies per cell (range, 0.21 to 21.6 copies per cell). Thus, the absence of viral inclusions in light microscopic observations and negative in situ hybridization results for biopsy tissue do not necessarily equate with total viral clearance from the renal allograft, although the average viral load is extremely low.

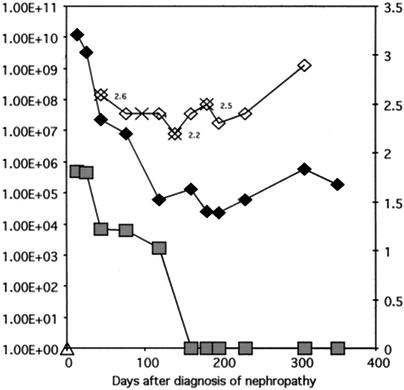

Viral loads in different clinical categories were statistically analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test, since the data did not pass the normality test. Viral loads in plasma, urine, and biopsy samples were higher in the active BKVAN group than in the asymptomatic viruria group or the resolved BKVAN group (P < 0.01). There was no statistically significant difference between data in the asymptomatic viruria group and data in the resolved BKVAN group. Serial evaluation of multiple samples from the same patient usually showed proportionate changes in viral loads in urine and plasma. However, patients who went on to resolve viral nephropathy typically showed clearance of viremia, with reduced but persistent viruria. For a representative patient treated for BKVAN, BK viral load was above the proposed cutoff of 1E+07 copies/ml of urine and 5E+03 copies/ml of plasma at the time of diagnosis but dropped below those levels after treatment. (Fig. 3). The serum creatinine level did not always fall despite the clearance of viral DNA from biopsy and plasma samples. This likely represents irreversible allograft injury caused by virus-induced damage to the kidney parenchyma.

FIG. 3.

Serial changes in viral load observed for a patient with BKVAN. Time zero on the x axis corresponds to the time of biopsy diagnosis of viral nephropathy. Reduction in immunosuppression and four doses of cidofovir (indicated by multipliers) resulted in clearance of viremia (shaded squares) and a reduction in viruria (solid diamonds). Serum creatinine levels (open diamonds) fluctuated and did not drop significantly despite the reduction in viral load. This phenomenon results from the confounding influence of chronic allograft nephropathy.

DISCUSSION

All patients with active nephropathy had detectable BKV in plasma (viremia). The association of circulating virus with active nephropathy has been noted before (4, 6, 7, 11). The entry of viral DNA in the circulation likely occurs at the level of peritubular capillaries, following tubular destruction and release of free virus in the interstitial compartment. The active BKVAN group generally showed higher levels of viruria than the resolved BKVAN group. This presumably reflects sloughing of virus-infected cells in the renal tubules and collecting ducts during the phase of active nephropathy. Nonetheless, some cases classified as resolved nephropathy based on routine histologic evaluation had urine and plasma viral loads comparable to those of other cases with active nephropathy. Potential explanations for this discrepancy include the inability of light microscopy to detect all infected tubules, sampling error, an extrarenal source of viral replication (in the pelvis, ureter, or urinary bladder), or a robust immune response that successfully prevented tissue damage despite a high concentration of virus in the tissue and body fluids.

The occurrence of viremia in five samples in the resolved BKVAN group appeared to be a transient finding. Follow-up samples obtained 7 to 31 days later showed clearance of virus from plasma. Biopsy sampling error should also be kept in mind during the clinical evaluation of such patients, particularly if urine examination shows decoy cells with an abundant inflammatory response (2). Another point of interest is the persistence of low levels of viral DNA in biopsy specimens of patients with resolved nephropathy, even when there was cessation of viruria. It is not clear whether this corresponds to latent virus or persistent low-level viral replication.

It is impractical to perform repeated biopsies to monitor the clinical course of BKVAN. Hence, we were particularly interested in determining whether persistent nephropathy could be predicted by noninvasive monitoring of virus loads in urine samples. Unfortunately, we could not determine any absolute cutoff levels that could distinguish the resolved BKVAN group from the active BKVAN group. Nonetheless, 26 of 27 (96%) urine samples in the resolved BKVAN group carried a viral load of <1E+07 copies/ml. The only sample that exceeded this cutoff was obtained within 12 days of a biopsy showing active BKVAN. Conversely, 10 of 15 (66.7%) urine specimens with a viral load of ≥1E+07 were associated with active BKVAN.

Attempts to determine a viremia cutoff appropriate for separating out cases with active nephropathy demonstrate the need to accept a tradeoff between the competing clinical requirements for sensitivity and specificity. A cutoff of 5E+03 copies/ml diagnoses all cases of BKVAN (100% sensitivity) but yields a false-positive diagnosis for 5 of 33 (15.2%) samples associated with asymptomatic viruria and 5 of 33 (15.2%) samples associated with resolved BKVAN. A stricter cutoff of 1E+05 copies/ml correctly classifies only 7 of 10 (70%) samples with active BKVAN (70% sensitivity) but reduces the false-positive diagnoses to 2 of 33 (6.1%) in samples from patients with resolved nephropathy and to 0 of 33 (0%) in samples associated with asymptomatic viruria. It is worth noting that the sensitivity of quantitative PCR varies from laboratory to laboratory. Hence, every medical center will need to establish its own cutoff values for the purposes of clinical management. For example, Hirsch et al. found viral nephropathy to be associated with plasma viral loads of >7.7E+03 copies/ml. In three of five cases the viral load exceeded 1.0E+07 copies/ml (4). Another caveat in this study is that biopsies were not performed for all patients at the same time that samples classified as asymptomatic viruria were collected. Hence, the possibility of occult nephropathy cannot be entirely excluded. In fact, one patient initially labeled as having asymptomatic viruria did go on to develop biopsy-proven nephropathy. On the other hand, biopsies are prone to sampling error, and we elected to treat one viremic patient with rising serum creatinine levels, 2.86E+07 viral copies/ml in urine, 1.22E+04 viral copies/ml in plasma, and a negative biopsy result as having BKV nephropathy on clinical grounds.

Patients with asymptomatic viruria showed urinary viral loads below our proposed BKVAN cutoff of 1E+07 copies/ml in 29 of 33 (87.8%) samples. One patient with 1.49E+09 copies/ml in urine subsequently developed viral nephropathy, as was noted above. These data confirm a widely held belief that persistent excretion of high levels of BKV DNA is a risk factor for the development of BKVAN. Viremia was observed in eight samples from five patients. Four of 10 biopsy samples tested in the group with asymptomatic viruria showed detectable viral DNA, with concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 152 copies per cell.

In conclusion, serial measurement of viral loads in urine or plasma by quantitative PCR is a useful tool in monitoring the course of BKV infection. The results should be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical picture and biopsy findings.

Acknowledgments

P.R. was supported by NIH grant R01 AI51227-01, Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center grant MCB020002P, and Satellite Healthcare Inc. A.V. was supported by the National Kidney Foundation of Western Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bjorang, O., H. Tveitan, K. Midtvedt, L. U. Broch, H. Scott, and P. A. Andresen. 2002. Treatment of polyomavirus infection with cidofovir in a renal-transplant recipient. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 17:2023-2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drachenberg, R. C., C. B. Drachenberg, J. C. Papadimitriou, E. Ramos, J. C. Fink, R. Wali, M. R. Weir, C. B. Cangro, D. K. Klassen, A. Khaled, R. Cunningham, and S. T. Bartlett. 2001. Morphological spectrum of polyoma virus disease in renal allografts: diagnostic accuracy of urine cytology. Am. J. Transplant. 1:373-381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Held, T. K., S. S. Biel, A. Nitsche, A. Kurth, S. Chen, H. R. Gelderblom, and W. Siegert. 2000. Treatment of BK virus-associated hemorrhagic cystitis and simultaneous CMV reactivation with cidofovir. Bone Marrow Transplant. 26:347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch, H. H., W. Knowles, M. Dickenmann, J. Passweg, T. Klimkait, M. J. Mihatsch, and J. Steiger. 2002. Prospective study of polyomavirus type BK replication and nephropathy in renal-transplant recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:488-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung, A. Y., M. Chan, S. C. Tang, R. Liang, and Y. L. Kwong. 2002. Real-time quantitative analysis of polyoma BK viremia and viruria in renal allograft recipients. J. Virol. Methods 103:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limaye, A. P., K. R. Jerome, C. S. Kuhr, J. Ferrenberg, M. L. Huang, C. L. Davis, L. Corey, and C. L. Marsh. 2001. Quantitation of BK virus load in serum for the diagnosis of BK virus-associated nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1669-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randhawa, P. S., and A. J. Demetris. 2000. Nephropathy due to polyomavirus type BK. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1361-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randhawa, P. S., S. Finkelstein, V. Scantlebury, R. Shapiro, C. Vivas, M. Jordan, M. M. Pickin, and A. J. Demetris. 1999. Human polyoma virus-associated interstitial nephritis in the allograft kidney. Transplantation 67:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randhawa, P. S., A. Vats, D. Zygmunt, P. A. Swalsky, V. Scantlebury, R. Shapiro, and S. Finkelstein. 2002. Quantitation of viral DNA in renal allograft tissue from patients with BK virus nephropathy. Transplantation 74:485-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scantlebury, V., R. Shapiro, P. S. Randhawa, K. Weck, and A. Vats. 2002. Cidofovir: a method of treatment for BK virus associated transplant nephropathy. Graft 5(Suppl.):S82-S86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vats, A., R. Shapiro, P. Randhawa, V. Scantlebury, A. Tuzuner, M. Saxena, M. L. Moritz, T. J. Beattie, T. Gonwa, M. D. Green, and D. Ellis. 2003. Quantitative viral load monitoring and cidofovir therapy for the management of BK virus-associated nephropathy in children and adults. Transplantation 75:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]