Abstract

Background

Evaluation of ≥12 lymph nodes after colon cancer resection has been adopted as a hospital quality measure, but compliance varies considerably. We sought to quantify relative proportions of the variation in lymph node assessment after colon cancer resection occurring at the patient, surgeon, pathologist, and hospital levels.

Methods

The 1998–2005 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results—Medicare database was used to identify 27,101 patients aged 65 years and older with Medicare parts A and B coverage undergoing colon cancer resection. Multilevel logistic regression was used to model lymph node evaluation as a binary variable (≥12 versus <12) while explicitly accounting for clustering of outcomes.

Results

Patients were treated by 4,180 distinct surgeons and 2,656 distinct pathologists at 1,113 distinct hospitals. The overall rate of 12-lymph node (12-LN) evaluation was 48%, with a median of 11 nodes examined per patient, and 33% demonstrated lymph node metastasis on pathological examination. Demographic and tumor-related characteristics such as age, gender, tumor grade, and location each demonstrated significant effects on rate of 12-LN assessment (all P<0.05). The majority of the variation in 12-LN assessment was related to non-modifiable patient-specific factors (79%). After accounting for all explanatory variables in the full model, 8.2% of the residual provider-level variation was attributable to the surgeon, 19% to the pathologist, and 73% to the hospital.

Conclusion

Compliance with the 12-LN standard is poor. Variation between hospitals is larger than that between pathologists or surgeons. However, patient-to-patient variation is the largest determinant of 12-LN evaluation.

Keywords: Colon cancer, Staging, Quality, Lymph node, Outcomes

Introduction

Colon cancer causes over 50,000 deaths per year in the USA, and over 100,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.1 Lymph node metastasis is a critical predictor of survival, and adequate ascertainment of lymph node status determines the use of adjuvant chemotherapy, which has been proven to improve survival.2 Adequate harvest and evaluation of lymph nodes is therefore essential to accurately identify those patients most likely to benefit from chemotherapy. In fact, increased lymph node harvest has been reported to be independently associated with improved long-term survival after colectomy for colon cancer.3–6 The National Quality Forum (NQF), in collaboration with the American College of Surgeons, American Society for Clinical Oncology, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network, has endorsed the evaluation of at least 12 lymph nodes after colon cancer resection as a hospital quality surveillance measure.7

Compliance with this 12-lymph node (12-LN) metric varies considerably, with only 44% of patients who underwent a colectomy in 2001 having 12 or more lymph nodes assessed.8 The reason for the wide variation in compliance is poorly understood. Factors that influence lymph node assessment may relate to the patient, surgeon, pathologist, or hospital. At the patient level, variations in lymph node yield may be related to age, gender, or tumor characteristics such as stage, grade, or site of resection.8–11 Patient-related determinants of lymph node examination are important to understand in order to fairly apply and standardize any quality measures related to lymph node assessment. Although not well studied, factors related to the surgeon, pathologist, or hospital are of special interest because, unlike most patient-related factors, they may be modifiable.12 Such data may also allow better targeting of hospital quality improvement efforts. The lack of provider-level data to explain the wide variability in compliance with the 12-LN standard has led some investigators to call its utility as a quality care measure into question.13

One problem in understanding the variation in lymph node assessment is that detailed provider-specific operative or pathological data are typically not available in population-based data sets. All retrospective studies are constrained by the variables available for analysis; some variation in outcome will inevitably remain unexplained by the finite number of variables included in explanatory models. A potentially useful approach, in addition to identifying individual variables that predict adequate lymph node assessment, is to quantify the relative proportions of the variation in lymph node assessment occurring at the patient, surgeon, pathologist, and hospital levels. Such an approach would allow targeting of quality improvement efforts at the appropriate level even when the relevant variables affecting care are not explicitly known. To our knowledge, no previous study has explicitly assessed variability at all of these levels. We sought to conduct such an analysis using the most recent available data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results—Medicare (SEER-Medicare) database.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

Using data from the 1998–2005 SEER-Medicare database,14,15 patients aged 65 years and older with Medicare parts A and B coverage undergoing curative-intent surgery for adenocarcinoma of the colon were identified. Patients with any previous cancer diagnosis, appendiceal tumors, and those with stage IV disease were excluded in accordance with NQF guidelines,7 as were those receiving preoperative radiation therapy. The number of lymph nodes examined for each patient is reported by SEER, and patients reported as having either no lymph nodes (n=654) or an unknown number examined (n=505) were excluded. Treating surgeons, pathologists, and hospitals were identified using encoded Unique Physician Identification Numbers from Medicare claims. Mean annual colon cancer volumes were calculated for each provider using the same cohort used for analysis, and for descriptive purposes, providers were grouped into terciles such that an approximately even number of patients were in each group. Previous studies have demonstrated that use of SEER-Medicare-derived volumes is an acceptable approach that has little impact on volume–outcome relationships for colon cancer, although some misclassification due to non-Medicare volume and SEER geographic boundaries does occur.16–18

Statistical Analysis

All variables for analysis were chosen based on clinical plausibility and were force-entered into the final model. Multilevel logistic regression was used to model lymph node evaluation as a binary variable (≥12 versus <12) with a nesting structure of patients nested within surgeons, nested within pathologists, and nested within hospitals (with each level of correlation representing a “cluster”). Random intercepts at each level were included in the model, allowing for additional variation at each level that was not explained by variables included in the model. Cluster-level variances at each level were obtained from both null (i.e., no explanatory variables) and full (i.e., all explanatory variables) models, with the patient-level variance constrained to π2/3 (by definition for the logistic distribution).19 These cluster-level variances were used to calculate the relative proportion of variance in lymph node assessment attributable to each level. To facilitate comparison with other explanatory variables, cluster-level variances were also expressed on the odds ratio (OR) scale using the median odds ratio, which quantifies the variation between clusters as the median value of odds ratios obtained by comparing sets of two patients from two randomly chosen, different clusters (e.g., two hospitals).20 All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and statistical significance was established at α=0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the GLLAMM package19 for Stata/MP 10.1 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). This study was deemed exempt from review by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Boards.

Results

Study criteria identified 27,101 eligible patients. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1, and tumor and operative characteristics are presented in Table 2. Of note, the majority of colon resections were right colectomies (n=15,701, 58%), and only 7% of all colectomies were performed laparoscopically (n=1,886). The majority of tumors were T3 lesions (n=16,183, 60%), and 33% demonstrated lymph node metastasis on pathological examination. Provider characteristics are presented in Table 3. The 27,101 patients in this study were treated by 4,180 distinct surgeons and 2,656 distinct pathologists at 1,113 distinct hospitals. The majority of colectomies were performed by general surgeons (n=23,349, 86%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Number | Percent | Percent with 12-LN assessment | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 27,101 | 48 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 65–69 | 4,362 | 16 | 50 | <0.001 |

| 70–74 | 5,575 | 21 | 49 | |

| 75–79 | 6,535 | 24 | 49 | |

| 80–84 | 5,716 | 21 | 48 | |

| >85 | 4,913 | 18 | 45 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 15,630 | 58 | 49 | <0.001 |

| Male | 11,471 | 42 | 46 | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 23,289 | 86 | 48 | <0.001 |

| Black | 2,021 | 7 | 49 | |

| Asian | 851 | 3 | 44 | |

| Hispanic | 359 | 1 | 36 | |

| Other/unknown | 581 | 2 | 51 | |

| Admission type | ||||

| Elective | 16,324 | 60 | 50 | <0.001 |

| Urgent | 5,483 | 20 | 47 | |

| Emergent | 5,294 | 20 | 44 | |

| In-hospital death | 976 | 4 | 38 | <0.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 1998 | 1,769 | 7 | 43 | <0.001 |

| 1999 | 1,816 | 7 | 42 | |

| 2000 | 3,600 | 13 | 42 | |

| 2001 | 3,785 | 14 | 44 | |

| 2002 | 4,072 | 15 | 48 | |

| 2003 | 4,144 | 15 | 49 | |

| 2004 | 4,011 | 15 | 53 | |

| 2005 | 3,904 | 14 | 56 |

Table 2.

Tumor and operative characteristics

| Variable | Number | Percent | Percent with 12-LN assessment | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of resection | ||||

| Right colectomy | 15,701 | 58 | 56 | <0.001 |

| Transverse colectomy | 1,492 | 6 | 34 | |

| Left colectomy | 3,492 | 13 | 40 | |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 6,178 | 23 | 35 | |

| Total colectomy | 238 | <1 | 65 | |

| Operative approach | ||||

| Open | 25,215 | 93 | 47 | <0.001 |

| Laparoscopic | 1,886 | 7 | 56 | |

| Tumor T classification | ||||

| T1 | 3,252 | 12 | 33 | <0.001 |

| T2 | 4,703 | 17 | 44 | |

| T3 | 16,183 | 60 | 52 | |

| T4 | 2,963 | 11 | 51 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| Yes | 8,900 | 33 | 53 | <0.001 |

| No | 18,201 | 67 | 46 | |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||

| Well | 2,261 | 8 | 42 | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 18,751 | 69 | 48 | |

| Poor | 5,255 | 19 | 54 | |

| Undifferentiated | 217 | <1 | 56 | |

| Unknown | 617 | 2 | 34 |

Table 3.

Provider characteristics

| Variable | Numbera | Percent | Percent with 12-LN assessment | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon specialty | ||||

| General surgery | 23,349 | 86 | 46 | <0.001 |

| Colorectal surgery | 3,521 | 13 | 61 | |

| Surgical oncology | 231 | <1 | 53 | |

| Surgeon volume | ||||

| Low volume (1–2) | 9,923 | 37 | 46 | <0.001 |

| Mid-volume (2–3) | 8,197 | 30 | 47 | |

| High volume (3–16) | 8,981 | 33 | 52 | |

| Pathologist volume | ||||

| Low volume (1–3) | 9,369 | 35 | 48 | 0.052 |

| Mid-volume (3–5) | 9,145 | 34 | 49 | |

| High volume (5–61) | 8,587 | 32 | 47 | |

| Hospital volume | ||||

| Low volume (1–7) | 9,068 | 33 | 42 | <0.001 |

| Mid-volume (7–14) | 9,084 | 34 | 48 | |

| High volume (14–51) | 8,949 | 33 | 55 | |

| Hospital control | ||||

| Non-profit | 21,873 | 81 | 50 | <0.001 |

| For-profit | 2,098 | 8 | 42 | |

| Government | 3,130 | 12 | 39 | |

| Teaching hospital | ||||

| Yes | 14,509 | 54 | 53 | <0.001 |

| No | 12,592 | 46 | 42 | |

| ACOSOG member | ||||

| Yes | 5,339 | 20 | 57 | <0.001 |

| No | 21,762 | 80 | 46 | |

| NCI designation | ||||

| None | 26,408 | 97 | 48 | <0.001 |

| Clinical center | 104 | <1 | 56 | |

| Comprehensive center | 589 | 2 | 67 | |

| Rural hospital | ||||

| Yes | 2,629 | 10 | 38 | <0.001 |

| No | 24,472 | 90 | 49 |

ACOSOG American College of Surgeons Oncology Group, NCI National Cancer Institute

Refers to number of patients

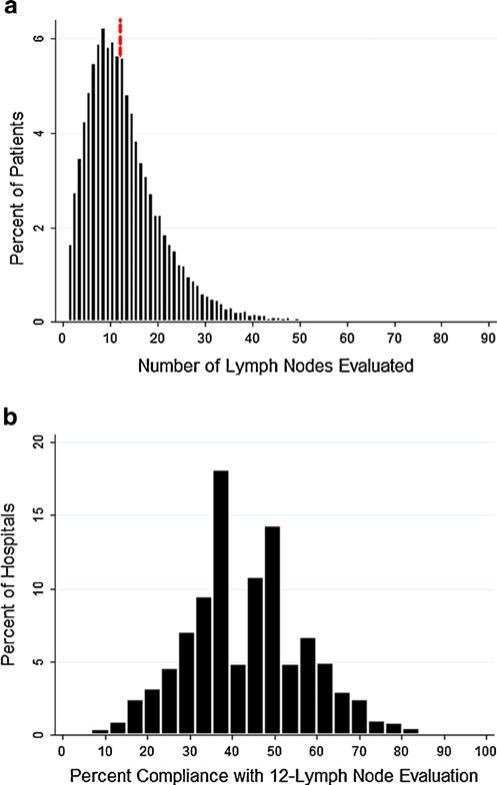

The overall compliance with 12-LN evaluation was 48% (n=13,003), with a median of 11 nodes examined per patient (Fig. 1a). Based on empirical Bayes estimates, the median percent compliance with 12-LN evaluation at the 1,113 hospitals was 43% (Fig. 1b). Rates of 12-LN assessment stratified by patient, tumor and operative characteristics, and provider characteristics are presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The effects of these characteristics were assessed using a multivariable multilevel logistic regression model that explicitly accounted for correlations in 12-LN assessment among patients treated by the same surgeon, pathologist, or hospital (Table 4). Demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and race demonstrated significant effects. Patients admitted to the hospital emergently rather than electively (OR 0.87, P<0.001) and those who died in the hospital (OR 0.67, P<0.001) had lower rates of 12-LN assessment. The type of colectomy had a pronounced effect (transverse versus right colectomy, OR 0.34, P<0.001), but there was no difference between laparoscopic and open approaches. The presence of any lymph node metastasis was associated with increased odds of 12-LN evaluation (OR 1.17, P<0.001).

Fig. 1.

The overall compliance with 12-LN evaluation was 48% (n=13,003), with a median of 11 nodes examined per patient (a; dotted line denotes 12-LN threshold). Based on empirical Bayes estimates, the median percent compliance with 12-LN evaluation at the 1,113 hospitals was 43% (b)

Table 4.

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis of 12-lymph node assessment

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–69 | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| 70–74 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.02 | 0.124 |

| 75–79 | 0.91 | 0.83–1.00 | 0.047 |

| 80–84 | 0.84 | 0.76–0.92 | <0.001 |

| >85 | 0.72 | 0.65–0.80 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.14 | 1.07–1.21 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Black | 0.99 | 0.88–1.12 | 0.883 |

| Asian | 0.81 | 0.67–0.98 | 0.030 |

| Hispanic | 0.62 | 0.48–0.80 | <0.001 |

| Other/unknown | 1.09 | 0.88–1.34 | 0.437 |

| Admission type | |||

| Elective | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Urgent | 0.96 | 0.89–1.04 | 0.365 |

| Emergent | 0.87 | 0.81–0.94 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital death | 0.67 | 0.58–0.79 | <0.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 1998 | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| 1999 | 0.93 | 0.79–1.09 | 0.352 |

| 2000 | 1.03 | 0.89–1.18 | 0.722 |

| 2001 | 1.18 | 1.02–1.35 | 0.022 |

| 2002 | 1.40 | 1.22–1.60 | <0.001 |

| 2003 | 1.43 | 1.24–1.64 | <0.001 |

| 2004 | 1.78 | 1.55–2.05 | <0.001 |

| 2005 | 2.15 | 1.86–2.48 | <0.001 |

| Type of resection | |||

| Right colectomy | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Transverse colectomy | 0.34 | 0.30–0.38 | <0.001 |

| Left colectomy | 0.44 | 0.41–0.48 | <0.001 |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 0.36 | 0.34–0.39 | <0.001 |

| Total colectomy | 1.46 | 1.07–2.00 | 0.016 |

| Laparoscopic resection | 0.94 | 0.83–1.06 | 0.325 |

| Tumor T classification | |||

| T1 | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| T2 | 1.81 | 1.62–2.02 | <0.001 |

| T3 | 2.81 | 2.54–3.10 | <0.001 |

| T4 | 2.59 | 2.28–2.94 | <0.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 1.17 | 1.10–1.25 | <0.001 |

| Tumor differentiation | |||

| Well | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Moderate | 1.12 | 1.00–1.25 | 0.049 |

| Poor | 1.16 | 1.03–1.32 | 0.018 |

| Undifferentiated | 1.40 | 0.99–1.96 | 0.054 |

| Unknown | 0.82 | 0.65–1.02 | 0.079 |

| Surgeon specialty | |||

| General surgery | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Colorectal surgery | 1.21 | 1.08–1.35 | 0.001 |

| Surgical oncology | 1.01 | 0.72–1.41 | 0.968 |

| Surgeon volume | |||

| Low volume | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Mid-volume | 1.06 | 0.98–1.14 | 0.151 |

| High volume | 1.10 | 1.00–1.19 | 0.039 |

| Pathologist volume | |||

| Low volume | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Mid-volume | 1.06 | 0.96–1.17 | 0.239 |

| High volume | 1.00 | 0.89–1.12 | 0.979 |

| Hospital volume | |||

| Low volume | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Mid-volume | 1.15 | 0.96–1.37 | 0.125 |

| High volume | 1.31 | 1.03–1.66 | 0.027 |

| Hospital ownership | |||

| Non-profit | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| For-profit | 0.89 | 0.73–1.09 | 0.274 |

| Government | 0.81 | 0.68–0.97 | 0.021 |

| Teaching hospital | 1.24 | 1.09–1.41 | 0.001 |

| ACOSOG member | 1.17 | 1.02–1.33 | 0.025 |

| NCI designation | |||

| None | 1.00 | – | Ref. |

| Clinical center | 1.88 | 0.79–4.46 | 0.152 |

| Comprehensive center | 2.57 | 1.59–4.14 | <0.001 |

| Rural hospital | 0.99 | 0.84–1.15 | 0.852 |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, Ref. referent, ACOSOG American College of Surgeons Oncology Group, NCI National Cancer Institute

Surgeon, pathologist, and hospital characteristics were also evaluated in the multivariable model (Table 4). Colorectal surgeons had higher rates of 12-LN assessment as compared to general surgeons (OR 1.21, P=0.001). There was a modest effect of surgeon volume (high volume versus low volume, OR 1.10, P=0.039) and a more pronounced effect of hospital volume (high volume versus low volume, OR 1.31, P=0.027), but no effect of pathologist volume, on 12-LN assessment. Among other hospital characteristics, treatment at a National Cancer Institute (NCI) comprehensive cancer center was associated with the largest difference in 12-LN assessment (OR 2.57, P<0.001). Teaching hospitals (OR 1.24, P=0.001) and American College of Surgeons Oncology Group member hospitals (OR 1.17, P=0.025) also achieved higher rates of 12-LN assessment.

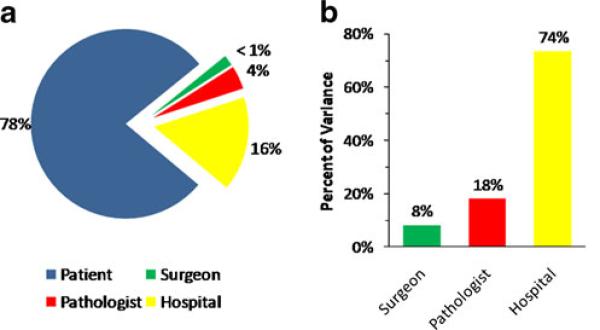

In aggregate, the majority of the variation in the 12-LN assessment was related to non-modifiable patient-specific factors (Fig. 2a). The modifiable provider-related variation in 12-LN assessment was then assessed in further detail (Table 5). In the null model that included no explanatory variables, 8.3% of provider-level variation occurred at the surgeon level, 18% at the pathologist level, and 74% at the hospital level (Fig. 2b). Similarly, after accounting for all explanatory variables in the full model, 8.2% of the residual provider-level variation was attributable to the surgeon, 19% to the pathologist, and 73% to the hospital. These quantities were transformed to the odds ratio scale to allow more intuitive interpretation of their significance alongside the explanatory factors in the multivariable model (Table 4). When viewed as median odds ratios, the surgeon-related effect was analogous to an odds ratio of 1.30, the pathologist-related effect 1.49, and the hospital-related effect 2.18. In all cases, cluster-level variances were significantly different from zero (P<0.05), indicating that the surgeon, pathologist, and hospital exerted statistically significant effects on 12-LN assessment rates in addition to the effects accounted for by variables in our model.

Fig. 2.

The majority of the variation in 12-LN evaluation was related to non-modifiable patient-specific factors (a). When the modifiable provider-related variation in 12-LN evaluation was assessed in further detail, 8% of provider-level variation occurred at the surgeon level, 18% at the pathologist level, and 74% at the hospital level (b)

Table 5.

Provider-level variation

| Level | Null model | Full modela |

|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | ||

| Share of total variation (%) | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Share of provider-related variation (%) | 8.3 | 8.2 |

| Median odds ratio | 1.30 | 1.30 |

| Pathologist | ||

| Share of total variation (%) | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| Share of provider-related variation (%) | 18 | 19 |

| Median odds ratio | 1.48 | 1.49 |

| Hospital | ||

| Share of total variation (%) | 16 | 16 |

| Share of provider-related variation (%) | 74 | 73 |

| Median odds ratio | 2.20 | 2.18 |

All P<0.05

Residual variation after accounting for all variables in Table 4

Discussion

Colorectal cancer lymph node examination rates have been a topic of considerable study and, recently, much debate.4,8,13,21–23 Based largely on retrospective observational studies3–6 that noted an independent association between increasing lymph node count and long-term survival, the assessment of 12 lymph nodes after colon cancer resection has been endorsed as a hospital quality surveillance standard.7 The use of lymph node count as a quality indicator has been criticized, however.13,21,22 Because variation in lymph node count is multifactorial, targeting quality improvement strategies based on evaluation of lymph node count is problematic.22 Variations in lymph node count have been noted at the patient,8,11,24,25 surgeon,26,27 pathologist,27–30 and hospital6,21,31 levels, but no previous study has quantified variation at all of these levels simultaneously. Understanding the factors that contribute to the number of lymph nodes evaluated is critical to targeting improvements in lymph node evaluation and, by extension, patient outcome. However, the relative contribution of each factor and exactly what or who (i.e., hospital versus surgeon versus pathologist) is being evaluated when interpreting lymph node count remains ill-defined. Additionally, the use of a multilevel framework allows variation at different levels of care to be quantified even if the specific variables acting at these levels are not explicitly defined in the available data. The present study quantitatively assesses these relative contributions and demonstrates that differences in lymph node count are largely related to patient-level variation. When potentially modifiable provider-related variability is specifically examined, hospital-level variation is much larger than pathologist- or surgeon-level variation. These results suggest that while significant determinants of adequate LN assessment remain out of the control of providers, provider-related variation in 12-LN evaluation is largely a hospital-level phenomenon.

A wide spectrum of provider-related factors may influence the quality of patient care and help explain variations in quality of care. The Donabedian framework organizes such factors into those related to structure or process and relates them to outcome.32 While conceptually useful, such a model belies the complex relationship between various structural factors such as case volume or hospital characteristics and process measures such as 12-LN assessment. Furthermore, no analysis of compliance with such process measures can exhaustively and explicitly identify all determinants of compliance. The use of population-based data, while allowing greater generalizability, further limits the variables available for analysis to those in the data set. For example, ascertaining whether a specific hospital had formally adopted an institution-wide quality-control program for 12-LN assessment was not feasible using SEER-Medicare data. In the present study, we addressed this issue by using a multilevel regression model that allowed us to characterize the variation at each level (patient, surgeon, pathologist, or hospital) without explicitly accounting for all the variables at that level. This approach allowed us to explore aspects of the variation in 12-LN assessment that have been inadequately studied by prior studies.

The relative contributions of surgeon versus pathologist in attaining the 12-LN count are one such ill-defined issue23,26 addressed by our analysis. Previous studies have suggested that differences in surgical technique or pathological examination may explain some of the variation in lymph node assessment.30,31,33–36 Rieger et al.26 compared the lymph node yield after colon cancer surgery of a single high-volume surgeon who operated at two hospitals with separate pathology departments. In this study, pathology provider A had a median LN count of 10 compared with 19 for pathology provider B. Of note, following an intervention in the pathology protocol at hospital A, the median lymph node yield increased to 12. In the present study, 8.2% of the residual provider-level variation was attributable to the surgeon, versus 19% to the pathologist. Collectively, these data suggest that the pathologist can have a significant influence on the number of lymph nodes reported. It is important to note, however, that most of the provider-related variation in lymph node count was not at the surgeon or pathologist level but rather at the hospital level (78%). In fact, the effect of hospital-level variation had a larger impact on 12-LN count than many other effects we studied, including surgeon and pathologist characteristics. The dominance of hospital-level variation does not imply that surgeons and pathologists have a less important role to play; we note that if a significant majority of surgeons or pathologists at a given hospital act cohesively as a group to improve lymph node evaluation, this would manifest as a hospital-level improvement. Some such hospital-level factors (e.g., teaching status, NCI designation) were explicitly accounted for in our analysis. Other such hospital-level factors were not identified in the SEER-Medicare data but were implicitly accounted for in the hospital-level variation. We speculated that these might include pathology departmentwide policies regarding adequacy of lymph node evaluation or insistence by surgeons at a hospital that final pathology reports include adequate lymph node review.

Our analysis revealed that most of the modifiable (i.e., non-patient) variation in 12-LN assessment occurs on the hospital level as a functional unit. While others have noted that hospital characteristics such as NCI center designation may be associated with lymph node assessment,37 these characteristics are likely proxies for hospital-level quality-control measures. Such data suggest that certain hospitals may have a higher baseline level of quality that may be generalized across other areas of care throughout that institution. This concept is based on the belief that shared elements of structures and processes of care across certain individual hospitals may relate to overall performance. With this in mind, future quality improvement measures aimed at lymph node assessment may be better directed at the hospital level rather than individual physicians.

Previous studies have largely focused exclusively on either hospital-level13,21 or patient-level (“biology”-related) factors.9,11 Past studies, however, have not addressed the relative importance of hospital versus patient factors associated with lymph node count variation. In the present study, we quantified provider-related variation using median odds ratios, allowing intuitive comparison between explanatory variables and residual provider-related variation on the odds ratio scale. For example, the median effect on 12-LN assessment of residual hospital-to-hospital variation was analogous to the effect of a left versus right colectomy. As such, these data call into question the usefulness of the 12-LN standard as a hospital quality surveillance measure. The current formulation of this measure does not, for example, account adequately for variations in patient and tumor characteristics (such as tumor location). We noted significant variation in 12-LN evaluation related to patient-specific factors such as patient age, tumor location, tumor stage, and tumor grade, as have previous studies.8,9,11,22 However, unlike any previous study, we included specific patient- and provider-level data in our explanatory model. In turn, we were able to demonstrate that individual patient-level variables exert larger effects on 12-LN assessment compared with provider-level factors, as the vast majority (78%) of residual variation was still attributable to patient-level factors even after accounting for all other variables in the model. As Baxter has noted,22 achieving the goal of adequate and consistent staging using a benchmark assumes that lymph node count does not vary substantially between individual patients. We would suggest that if a benchmark is to be used in the presence of such patient-to-patient variation, the reporting standards should at least be sufficiently standardized as to insulate the measure from such case mix variation as much as possible. If the impact of patient-level variation on the number of lymph nodes evaluated is indeed as great or even greater than that of provider-level variation, as our analysis demonstrates, then quality measures such as the 12-LN benchmark need to be standardized with respect to the relevant patient and tumor characteristics. Our data, therefore, clearly call into question the use of 12-LN quality measure as currently formulated. Rather, our data strongly suggest that if the 12-LN benchmark is to be retained as a hospital quality measure, the guideline needs to extensively account for differences in patient case mix.

We acknowledge several limitations to our analysis. First, we focused on patients aged 65 years and older because of our reliance on Medicare data for this study. While we would expect compliance rates with the 12-LN rates to be higher in younger patients, we would not expect a priori that our conclusions regarding variation in compliance to be significantly different—however, other studies would need to verify this hypothesis. Second, in assessing provider-level variables, we were limited to those available in the SEER-Medicare data. However, this was a major reason that we used a modeling approach that allowed quantification of variability without needing to explicitly identify all important variables at each level. We also did not specifically examine the impact of laparoscopic versus open colectomy on 12-LN rates. Previously published randomized data,38 however, have shown that the median number of harvested lymph nodes in laparoscopic versus open colectomy was similar. As such, these data suggest that the impact of increasing utilization of laparoscopic colectomy was unlikely to impact our findings. Finally, SEER data are based on a geographic sampling and as such do not guarantee representative sampling of hospitals and physicians with respect to the provider-level characteristics we evaluated. Again, other sources of data will need to be used to corroborate our findings.

In conclusion, overall compliance with the 12-LN evaluation standard after colon cancer resection is poor, although it has improved over time. While variation in lymph node count can in part be attributed to differences among pathologists and surgeons, the largest share of modifiable variation was found to be at the hospital level. Importantly, however, patient-to patient variation was much greater than that attributable to health care providers, both with respect to individual patient-specific factors and the residual variation after accounting for such variables. The 12-LN threshold may, in part, be a “quality” measure. However, our data strongly suggest that while some determinants of lymph node assessment are provider-related, much of the variation in LN assessment is due to hospital and patient-level factors. As such, our findings suggest that the 12-LN hospital quality measure should be cautiously used and that its reporting should be more rigorously standardized.

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Footnotes

Presented at the 50th Annual Meeting of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, June 2, 2009, Chicago, IL.

Contributor Information

Hari Nathan, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Andrew D. Shore, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Robert A. Anders, Department of Pathology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Elizabeth C. Wick, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Susan L. Gearhart, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Timothy M. Pawlik, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 N Wolfe St, Halsted 611, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA tpawlik1@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sargent D, Sobrero A, Grothey A, et al. Evidence for cure by adjuvant therapy in colon cancer: observations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients on 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:872–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen SL, Bilchik AJ. More extensive nodal dissection improves survival for stages I to III of colon cancer: a population-based study. Annals of surgery. 2006;244:602–10. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237655.11717.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2912–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart AK, Bland KI. The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined. Annals of surgical oncology. 2003;10:65–71. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bui L, Rempel E, Reeson D, Simunovic M. Lymph node counts, rates of positive lymph nodes, and patient survival for colon cancer surgery in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study. Journal of surgical oncology. 2006;93:439–45. doi: 10.1002/jso.20499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Quality Forum National voluntary consensus standards for quality of cancer care: a consensus report. (Accessed at http://www.qualityforum.org/pdf/reports/Cancer_Nonmember_Report.pdf.)

- 8.Baxter NN, Virnig DJ, Rothenberger DA, Morris AM, Jessurun J, Virnig BA. Lymph node evaluation in colorectal cancer patients: a population-based study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:219–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright FC, Law CH, Berry S, Smith AJ. Clinically important aspects of lymph node assessment in colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:248–55. doi: 10.1002/jso.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tekkis PP, Smith JJ, Heriot AG, Darzi AW, Thompson MR, Stamatakis JD. A national study on lymph node retrieval in resectional surgery for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1673–83. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Palis BE, Bentrem DJ, Talamonti MS, Ko CY. Adequacy and importance of lymph node evaluation for colon cancer in the elderly. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2008;206:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etzioni D, Spencer M. Nodal harvest: surgeon or pathologist? Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:366–7. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9113-3. author reply 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Kulaylat M, Rockette H, et al. Should total number of lymph nodes be used as a quality of care measure for stage III colon cancer? Ann Surg. 2009;249:559–63. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318197f2c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40:IV–3-18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nathan H, Pawlik TM. Limitations of claims and registry data in surgical oncology research. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:415–23. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346:1128–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrag D, Bach PB, Dahlman C, Warren JL. Identifying and measuring hospital characteristics using the SEER-Medicare data and other claims-based sources. Medical care. 2002;40:IV–96-103. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollenbeck BK, Hong J, Zaojun Y, Birkmeyer JD. Misclassification of hospital volume with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Medicare data. Surg Innov. 2007;14:192–8. doi: 10.1177/1553350607307274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using STATA (ed 2) STATA; College Station: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:81–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong SL, Ji H, Hollenbeck BK, Morris AM, Baser O, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital lymph node examination rates and survival after resection for colon cancer. Jama. 2007;298:2149–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baxter NN. Is lymph node count an ideal quality indicator for cancer care? J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:265–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson PM, Porter GA, Ricciardi R, Baxter NN. Increasing negative lymph node count is independently associated with improved long-term survival in stage IIIB and IIIC colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3570–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2654–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rieger NA, Barnett FS, Moore JW, et al. Quality of pathology reporting impacts on lymph node yield in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2304. author reply-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostadi MA, Harnish JL, Stegienko S, Urbach DR. Factors affecting the number of lymph nodes retrieved in colorectal cancer specimens. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2142–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson PM, Malatjalian D, Porter GA. Adequacy of nodal harvest in colorectal cancer: a consecutive cohort study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:883–88. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00131-2. discussion 9–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans MD, Barton K, Rees A, Stamatakis JD, Karandikar SS. The impact of surgeon and pathologist on lymph node retrieval in colorectal cancer and its impact on survival for patients with Dukes’ stage B disease. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:157–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemmens VE, van Lijnschoten I, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Rutten HJ, Verheij CD, Coebergh JW. Pathology practice patterns affect lymph node evaluation and outcome of colon cancer: a population-based study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1803–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pheby DF, Levine DF, Pitcher RW, Shepherd NA. Lymph node harvests directly influence the staging of colorectal cancer: evidence from a regional audit. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:43–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.57.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? Jama. 1988;260:1743–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bull AD, Biffin AH, Mella J, et al. Colorectal cancer pathology reporting: a regional audit. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:138–42. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller EA, Woosley J, Martin CF, Sandler RS. Hospital-to-hospital variation in lymph node detection after colorectal resection. Cancer. 2004;101:1065–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris EJ, Maughan NJ, Forman D, Quirke P. Identifying stage III colorectal cancer patients: the influence of the patient, surgeon, and pathologist. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2573–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelder W, Inberg B, Plukker JT, Groen H, Baas PC, Tiebosch AT. Effect of modified Davidson's fixative on examined number of lymph nodes and TNM-stage in colon carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Stewart AK, et al. Lymph node evaluation as a colon cancer quality measure: a national hospital report card. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1310–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2050–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]