Abstract

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strains are capable of suppressing soilborne pathogens through the secretion of an array of lipopeptides and root colonization, and biofilm formation ability is considered a prerequisite for efficient root colonization. In this study, we report that one of the lipopeptide compounds (bacillomycin D) produced by the rhizosphere strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 not only plays a vital role in the antagonistic activity against Fusarium oxysporum but also affects the expression of the genes involved in biofilm formation. When the bacillomycin D and fengycin synthesis pathways were individually disrupted, mutant SQR9M1, which was deficient in the production of bacillomycin D, only showed minor antagonistic activity against F. oxysporum, but another mutant, SQR9M2, which was deficient in production of fengycin, showed antagonistic activity equivalent to that of the wild-type strain of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9. The results from in vitro, root in situ, and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR studies demonstrated that bacillomycin D contributes to the establishment of biofilms. Interestingly, the addition of bacillomycin D could significantly increase the expression levels of kinC gene, but KinC activation is not triggered by leaking of potassium. These findings suggest that bacillomycin D contributes not only to biocontrol activity but also to biofilm formation in strain B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9.

INTRODUCTION

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum is the primary cause of vascular wilt in cucumber plants, and it causes substantially reduced cucumber yields in China (1–3). The symptoms of the disease begin with the development of necrotic lesions, followed by foliar wilting as the pathogen invades the vascular system of the plant, and eventually, plant death (4). Chemical fungicides and soil disinfestations by treating with methyl bromide are the main strategies for controlling cucumber Fusarium wilt. However, with increasing concern over fungicide resistance, environment pollution, and food safety (5), biological control has attracted considerable attention (6).

Many biocontrol agents have been reported (7–9). Among the most promising candidates are several species of the genus Bacillus, which are ubiquitously occurring safe microorganisms with proven excellent colonization aptitudes (10), and versatility in effectively protecting plants from pathogens (11–13). The main mechanisms by which biocontrol agents (BCAs) suppress pathogens are antibiosis, competition, growth promotion, and induction of systemically acquired resistance (14, 15). Antibiotic production may also play an important function in their biocontrol activities (10). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 has as much as 8.5% of its genome devoted to the synthesis of antibiotics and the synthesis of siderophores by pathways not involving ribosomes (16). Among these antimicrobial compounds, cyclic lipopeptides (LPs) of the iturin, fengycin (or plipastatin), and surfactin families have well-recognized potential uses in biotechnology and biopharmaceutical applications because of their surfactant properties. The iturin and fengycin families display strong in vitro antifungal activities against a wide variety of fungi, whereas the surfactin family shows minimal antifungal activity (5).

Colonization of root is a prerequisite for successful control of soilborne pathogen by BCAs (17), which depend on the capability of biofilm formation. It is now widely recognized that most bacteria found in natural, clinical, and industrial settings persist in association with surfaces by forming biofilms (18). Biofilms are structured communities of cells adherent to a surface and encased in an extracellular polymeric matrix (19–21). The site of one such ecologically beneficial bacterial community is the rhizosphere, where a rich microflora develops around the readily available nutrients released by roots (22). It is hypothesized that in this environment, the microbial populations attached to the roots and the surrounding soil particles may form biofilm communities. Bacteria attach to the root surface using a variety of cell surface components, such as outer membrane proteins, wall polysaccharides, lipopolysaccharide, cell surface agglutinin, and exopolysaccharide (23). Characterization of mutants defective in biofilm formation and development in several genera of both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria has begun to reveal some of gene products that are involved in biofilm formation; these gene products include motility, cell surface structure, and exopolysaccharide (21).

Bacterially produced antibiotics usually act as weapons to compete with other microorganisms or pathogens with regard to BCAs, but it has been reported that at subinhibitory concentrations, some antibiotics stimulate the bacterial biofilm formation through hormesis effect (24). Surfactin produced by B. subtilis was demonstrated to be necessary for biofilm formation, root colonization, and successful biocontrol of plant pathogen (19). In addition, some polyketide (nystatin) and cyclic lipopeptide (surfactin) products trigger biofilm formation of B. subtilis through the leakage of potassium, which stimulates the activity of KinC and thus upregulates the biofilm formation-related genes (25). KinC is a membrane protein kinase which governs the expression of genes involved in biofilm formation.

B. subtilis SQR9 (now reidentified as B. amyloliquefaciens) isolated from cucumber rhizosphere suppressed the growth of F. oxysporum in the rhizosphere and protected the host from pathogen invasion through efficient root colonization (26). In vitro testing showed that the supernatant of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 completely inhibited the conidial germination of F. oxysporum, implying that it might contain antifungal compounds. In this study, the antifungal LPs were investigated using both biochemical and genetic approaches. In vitro tests and gene disruption experiments confirmed that among the detected LPs, bacillomycin D was the major compound responsible for the inhibition of F. oxysporum. We also demonstrated that bacillomycin D was necessary in B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 biofilm formation through the transcription stimulation of kinC and other biofilm formation genes independent of the potassium leakage mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. E. coli TOP10 was used as the host for all plasmids. B. amyloliquefaciens strain SQR9 (CGMCC accession no. 5808; China General Microbiology Culture Collection Center) was used throughout this study. Fusarium oxysporum CIPP1012 (ACCC accession no. 30220; Agricultural Culture Collection of China) was used as the pathogen and was obtained from the institute of vegetables and flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China).

Table 1.

Microorganisms and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Fungus | ||

| F. oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum J. H. Owen (FOC NJAU-2) | Laboratory stock (26) | |

| Bacteria | ||

| E. coli Top10 | F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 nupG recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galE15 galK16 rpsL (Strr) endA1 λ− | Invitrogen (Shanghai) |

| B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42 | Control strain with LP production | 16 |

| B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 | Wild type | 26 |

| B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9-gfp | GFP-labeled B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9; Kanr | 26 |

| B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9M1 | B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 ΔbamD::Tc | This study |

| B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9M2 | B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 ΔfenA::Tc | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMD 18-T | TaKaRa (Dalian) | |

| pBR322 | TaKaRa (Dalian) |

Growth conditions.

Bacteria strains were cultivated routinely on GB broth (glucose, 10 g liter−1; peptone, 10 g liter−1; beef extract, 2 g liter−1; yeast extract, 1 g liter−1; NaCl, 5 g liter−1) (27) solidified with 1.5% agar. For lipopeptide production and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometer (LC-MS) characterization, the bacteria were grown in Landy medium (28). When required, antibiotics were added to a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1 for ampicillin (Amp) or 20 μg ml−1 for tetracycline (Tet).

Identification of lipopeptides produced by B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9.

To identify and characterize the lipopeptides produced by B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9, the supernatant of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 was analyzed by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and LC-MS as described previously (29). B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 was grown in Landy medium at 30°C for 60 h, and the lipopeptides were then isolated by acid precipitation with concentrated HCl at pH 2.0. The precipitate was recovered by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min, washed twice by acidic deionized water (pH 2.0), and then extracted twice with methanol (28). The pooled extraction solution was dried with a rotary vacuum evaporator, and the residue was dissolved in 1 ml of phosphorous buffer (PBS; 0.01 M [pH 7.4]). The supernatant of SQR9 was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size hydrophilic membrane.

LPs were separated by RP-HPLC equipped with reversed-phase C18 analytical column (9.4 by 150 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The flow rate was 0.84 ml/min using gradient elution with a detecting wavelength of 210 nm. Mobile phase A and mobile phase B were acetonitrile and 0.1% acetic acid in water, respectively. The elution conditions were from 0 to 9 min 60 to 93% (vol/vol) mobile phase A plus 40 to 7% (vol/vol) mobile phase B and from 9 to 20 min 93% mobile phase A and 7% mobile phase B. An Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole LC/MS apparatus (Agilent Technologies) was used to determine the molecular weights of the antifungal compounds identified by RP-HPLC. The electrospray needle was operated at a spray voltage of 4.5 KV and a capillary temperature of 300°C. The mobile-phase components were acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% acetic acid (B) in water at a ratio of 70:30 with a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1. The MS analysis was done by electrospray ionization in positive ion mode.

Bioassay of antagonistic activities against F. oxysporum of the RP-HPLC eluted fractions, B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 and its mutants.

B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 was grown in Landy medium at 30°C for 60 h, and the lipopeptides were isolated as previously described. The antifungal activities of the six fractions were separated, collected by RP-HPLC and tested on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates. A volume of 30 μl of collected fraction was dropped into an Oxford cup placed 2 cm from the edge of a petri plate and allowed to diffuse into agar. A plug (about 1 cm in diameter) of F. oxysporum from a 5-day-old (25°C) PDA plate of the growing F. oxysporum was placed in the center. The plates were then incubated at 25°C, and the distance between the edges of the petri dish and the fungal mycelium were measured after 5 days. The experiment was repeated three times. To determine the roles of lipopeptides from B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 in biological control of F. oxysporum, bmyD and fenA genes were disrupted by double cross-recombination. The antifungal activities of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 and its mutants against F. oxysporum were tested using the same method. A volume of 30 μl of supernatant of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 and its mutants (incubated in Landy medium at 30°C for 60 h) was loaded in an Oxford cup.

Conidial germination inhibition bioassay.

The supernatants of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 and its mutants were tested in the antifungal assay. The conidia of F. oxysporum were used as targets, and the concentration of conidial suspension was adjusted to 105 conidia ml−1. In each test, 25 μl of supernatant (or diluted supernatant) was mixed with 25 μl of conidial suspension and incubated at 25°C for 12 h. One hundred conidia were selected randomly under a light microscope, and the percentage of inhibition was calculated (number of ungerminated conidia/100). The experiment was repeated three times.

Biofilm assay of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 and its mutants.

Biofilm assay was carried out using a modified version of the microtiter plate as described by Homon and Lazazera (30). B. amyloliquefaciens cells were grown in 24-well polyvinylchloride (PVC) microtiter plates (Fisher Scientific) at 37°C in biofilm growth medium (MSgg medium, 5 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7], 100 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [pH 7], 2 mM MgCl2, 700 μM CaCl2, 50 μM MnCl2, 50 μM FeCl3, 1 μM ZnCl2, 2 mM thiamine, 0.5% glycerol, 0.5% glutamate, 50 μg of tryptophan ml−1, 50 μg of phenylalanine ml−1, and 50 μg of threonine ml−1). The inoculum for the microtiter plates was obtained by growing the cells in MSgg medium with shaking to mid-exponential growth and then diluting the cells to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01 in fresh biofilm growth medium. Samples of 100 μl of the diluted cells were then aliquoted to each well of a 24-well PVC microtiter plate. The microtiter plates were incubated under stationary condition at 37°C.

At various time points during the incubation of B. amyloliquefaciens strains in the microtiter plates, the presence of adhered cells was monitored by staining with crystal violet (CV). Growth medium and nonadherent cells were removed from the microtiter plate wells, which were then rinsed with washing buffer (0.15 M ammonium sulfate, 100 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7], 34 mM sodium citrate, and 1 mM MgSO4). Biofilm cells were stained with 1% CV in washing buffer at room temperature for 20 min. Excess CV was then removed, and the wells were rinsed with water. The CV that had stained the cells was then solubilized in 200 μl of 80% ethanol–20% acetone. Biofilm formation was quantified by measuring the OD570 for each well using a Bio-Rad model 550 plate reader.

Transcription analysis of genes involved in biofilm formation.

RNA were isolated from B. amyloliquefaciens strains (SQR9, SQR9M1, and SQR9M2) in MSgg medium during biofilm formation. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C (10 min, 5,000 × g). Total RNA samples were extracted using an RNAiso Plus kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA in a 20-μl reverse transcription system (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transcription levels of epsD, yqxM, and kinC of SQR9M1 and SQR9M2 relative to SQR9 were measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Perfect Real Time) kit (TaKaRa). epsD and yqxM, genes of epsA-O and yqxM-sipW-tasA operons, are two critical genes for production of exopolysaccharide (EPS) and TasA, respectively, and essential for proper biofilm development. The sequences of primers used to amplify these genes are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The recA gene was used as an internal control. Reactions were carried out on an ABI 7500 system under the followed condition: cDNA was denatured for 10 s at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95°C and 34 s at 60°C. The method of 2−ΔΔCT was use to analyze the real-time PCR data (31).

Root colonization of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 strains.

To study root colonization, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 (SQR9-gfp) (26) was used instead of SQR9 to facilitate the monitoring. Colonies of B. amyloliquefaciens strains (SQR9-gfp, SQR9M1, and SQR9M2) were inoculated into 50 ml of LB broth with appropriate antibiotics, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C until reaching the stationary phase (about 20 h). The cells were washed twice in M8 buffer (22 mM Na2HPO4, 22 mM KH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl) and resuspended in 500 ml of M8 buffer prior to use. Axenic prepared cucumber seedlings were soaked in 500 ml of bacterial suspension for 30 min at 30°C. Then, the seedlings were aseptically transplanted to containers with 200 ml of sterile 1/2 MS culture medium. The plants were incubated in a growth chamber at 28°C with a 16-h light regimen. Ten repeats were performed for each strain.

To monitor B. amyloliquefaciens strains colonized on cucumber seedling roots, root samples were taken after 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 15 days of inoculation (17), and 0.2 g of roots were homogenized in 1.8 ml of PBS buffer using a mortar and pestle until a fine homogenate was obtained. The homogenates were serially diluted and plated onto LB plates (20 μg of kanamycin ml−1 for SQR9-gfp, 20 μg of tetracycline ml−1 for SQR9M1 and SQR9M2). B. amyloliquefaciens strains colonized on cucumber seedling roots were determined.

Statistical analysis.

The data were statistically analyzed using analysis of variance, followed by the Fisher least-significant-difference test (P < 0.05) using SPSS software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Collection and antifungal activity examination of LP compounds in B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9.

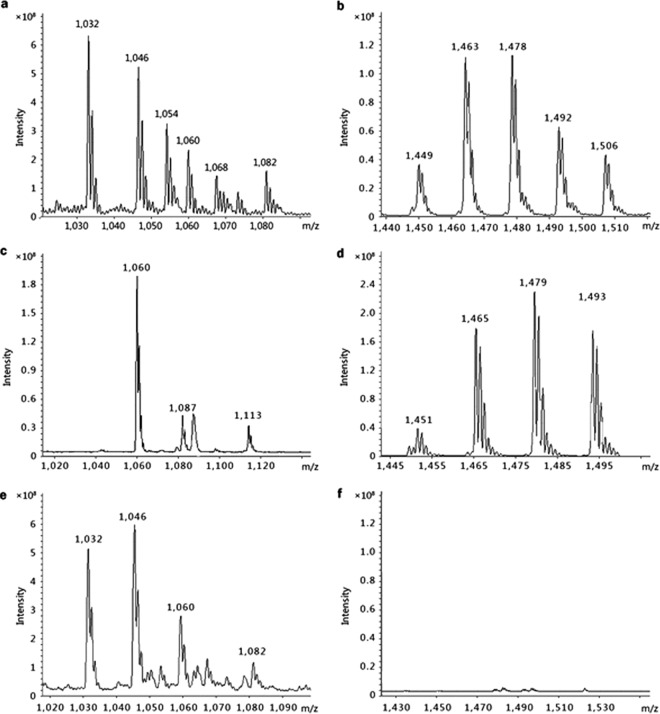

Bacillus-produced LPs are responsible for the antifungal activities; most Bacillus strains produce an array of LPs, which work synergistically or separately to antagonize fungal pathogens (10). B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 showed efficient biocontrol activity against the pathogen of Fusarium oxysporum known to cause cucumber wilt (26). To elucidate the antagonistic mechanism of the LPs on the fungi, the LP products of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 were investigated by RP-HPLC. Three-day-old supernatants were separated by RP-HPLC. Six eluted fractions were collected (Fig. 1A), and their antifungal activities were examined (Fig. 1B). The results showed that only two fractions, eluting at 2.9 and 3.8 min, respectively, inhibited the growth of F. oxysporum. The fraction eluted at 2.9 min was more effective at antagonizing F. oxysporum than the fraction eluted at 3.8 min. In addition, the production of peak a was much higher than that of peak b in B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9.

Fig 1.

(A) Reversed-phase HPLC chromatograms of lipopeptides produced by B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9. B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 was grown in Landy medium at 30°C for 60 h, and the lipopeptides were acid precipitated and extracted. The six peaks from left to right are indicated. (B) Antagonistic activities against F. oxysporum of the six fractions separated and collected by RP-HPLC. A volume of 30 μl of collected fraction was dropped into an Oxford Cup placed on a PDA agar plate with actively growing F. oxysporum. The plates were incubated for 4 days at 25°C. The “a” represents the fraction eluted from RP-HPLC of peak a, and the same pattern is used for other fractions.

Identification of the antifungal compounds in B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9.

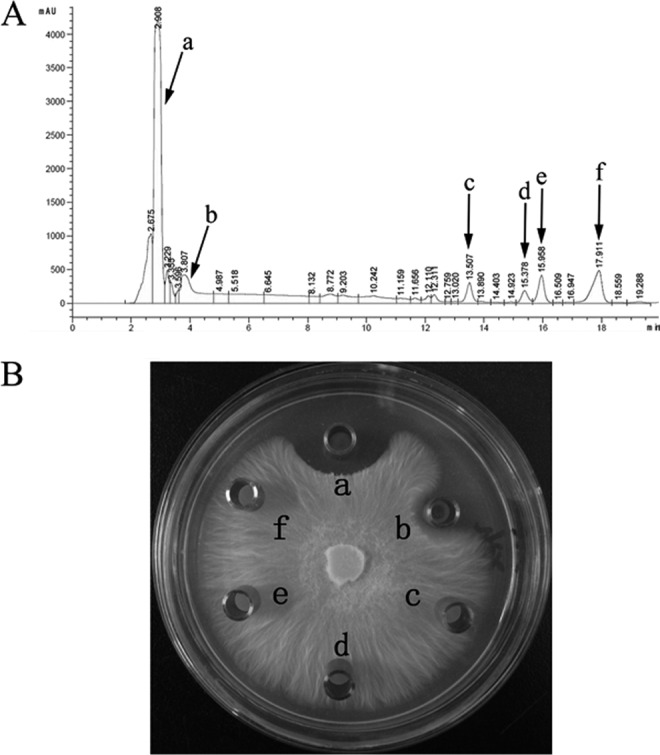

The two fractions with F. oxysporum antagonistic activities were further analyzed by LC-MS. The MS data are summarized in Table S2 in the supplemental material, and the mass peak profiles are illustrated in Fig. 2a and b, respectively. The two fractions were identified as bacillomycin D and fengycin based on the comparisons of these MS data with fractions previously identified by MS analysis in other B. amyloliquefaciens strains (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) (12).

Fig 2.

LC-MS analysis of bacillomycin D (a, c, and e) and fengycin (b, d, and f) from B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 (a and b), the bmyD-disrupted mutant strain SQR9M1(c and d), and the fenA-disrupted mutant strain SQR9M2 (e and f). All strains were grown in Landy medium at 30°C for 5 days. The supernatant was acid precipitated and extracted, and the fractions at the indicated retention times of bacillomycin D and fengycin were eluted and further analyzed by MS.

Disruption of bmyD and fenA genes blocked the synthesis of bacillomycin D and fengycin in B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9.

Because commercial pure bacillomycin D and fengycin were not available to confirm their roles in the F. oxysporum control, the bamD and fenA genes were disrupted. Then, the mutants SQR9M1 and SQR9M2, which were PCR verified with the primer sets p17/p18 and p19/p20 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), respectively, were confirmed by Southern blotting experiments (data not shown). The supernatant of both mutants were analyzed by LC-MS (Fig. 2c to f), and results showed that the mass peaks of bacillomycin D were not present in the supernatant of SQR9M1 (Fig. 2c). However, fengycin was still produced (Fig. 2d). For SQR9M2, the bacillomycin D production was similar to the wild-type strain B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 (Fig. 2e), but the MS peaks of fengycin were absent (Fig. 2f).

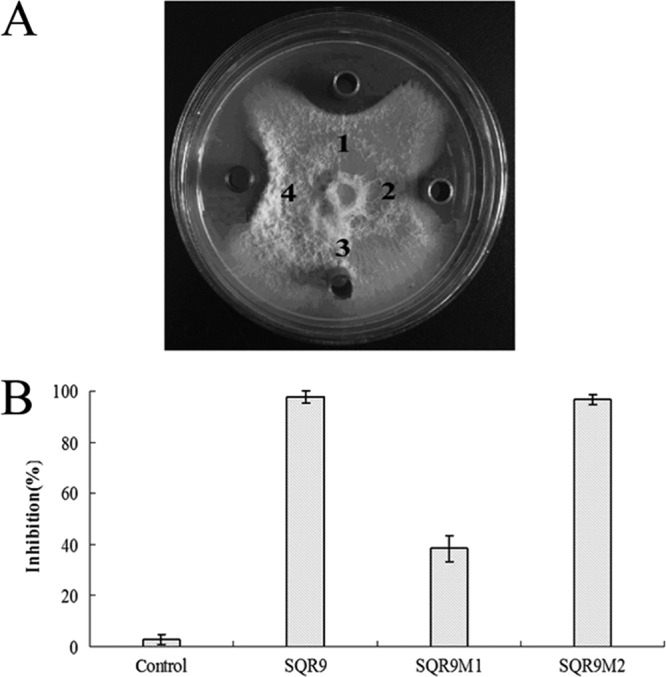

bmyD- and not the fenA-disrupted mutant impaired the antagonistic activity against F. oxysporum.

The bmyD- and fenA-disrupted mutants, SQR9M1 and SQR9M2, as well as wild-type strain B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 were tested and compared for their antagonistic activity against F. oxysporum. On a potato dextrose agar (PDA) plate, the supernatant of wild-type strain B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 inhibited the mycelial growth of F. oxysporum efficiently (Fig. 3A), and the average distance between the edges of petri dish and the fungal mycelium was 1.83 ± 0.12 cm. Under the same condition, the supernatant of SQR9M1 only showed minor antifungal activity against F. oxysporum, with the average distance between the edges of petri dish and the mycelium being about 0.34 ± 0.05 cm. The disruption of fenA had almost no effect on the antifungal activity against F. oxysporum. These data confirmed the hypothesis that the LP fraction of bacillomycin D plays a major role in F. oxysporum inhibition.

Fig 3.

(A) Antagonistic activities against F. oxysporum of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 (spot 1), and the bmyD-disrupted mutant strain SQR9M1 (spot 2), the methanol control (spot 3), and the fenA-disrupted mutant strain SQR9M2 (spot 4). A volume of 30 μl of a 50-h culture grown in Landy medium was dropped into Oxford Cups placed on PDA agar plates with actively growing F. oxysporum. The plates were incubated at 25°C for 7 days. (B) Effects of supernatant drawn from SQR9 and the mutants impaired in the biosynthesis of bacillomycin D (SQR9M1) and fengycin (SQR9M2) on the germination of conidia of F. oxysporum with a final concentration at 50%.

In the in vitro bioassay evaluating the supernatant of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 mutants for their capacities of inhibiting F. oxysporum conidial germination, the conidia of F. oxysporum treated with gradually diluted supernatants of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 were checked for their germination. The results indicate that 2-fold dilution of supernatant of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 inhibited the germination of F. oxysporum conidia effectively (98%) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and this dilution was used for further comparison. Significant differences of inhibition rates were obtained after 12 h of incubation, which were 98, 40, and 96% for SQR9, SQR9M1, and SQR9M2, respectively (Fig. 3B).

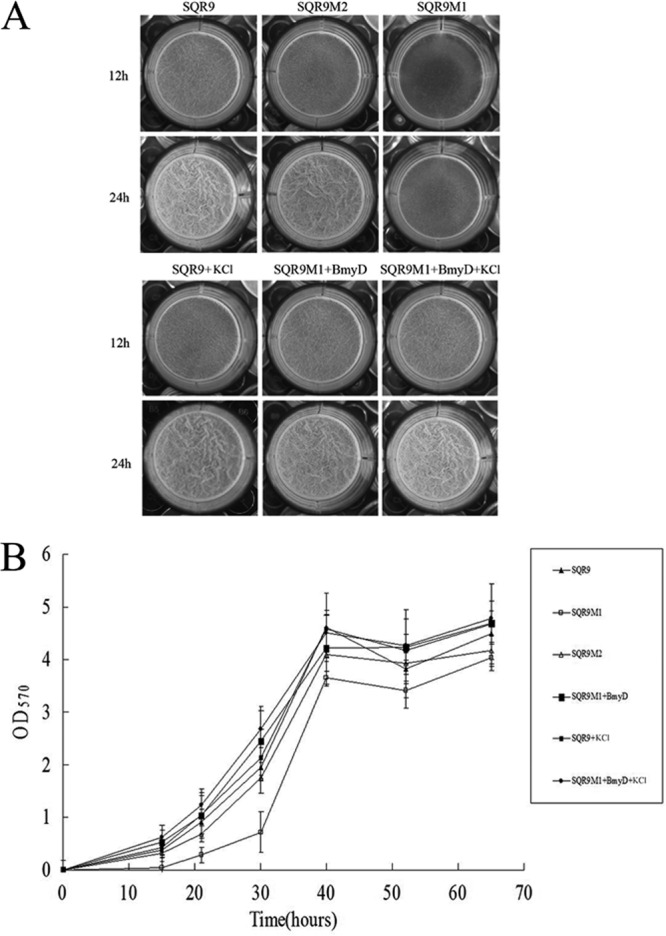

Bacillomycin D is necessary for biofilm formation of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9.

Biofilm assay with microtiter plates at both 12- and 24-h time points showed that SQR9M1 formed a thin and fragile biofilm compared to wild-type strain SQR9, which had no difference with the biofilm of strain SQRM2 (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analysis of the biofilm biomass indicated the bacillomycin D mutant exhibited significantly lower levels of biofilm biomass until 40 h, when the biofilms formed by mutants and wild-type strain appeared similar (Fig. 4B). Planktonic bacterial cells of each strain in the plate wells were counted by colony formation and found similar (data not shown). In addition, the three strains showed indistinctive growth curves (Fig. S1). When bacillomycin D (purified by RP-HPLC and identified by LC-MS since the commercial bacillomycin D is not available) was added to strain SQR9M1 medium, the biofilm was restored to the level of wild-type strain SQR9 (Fig. 4A and B); these results indicate that bacillomycin D is necessary for SQR9 to form biofilm.

Fig 4.

Microtiter plate assay of biofilm formation by wild-type and mutant B. amyloliquefaciens strains. (A) Wild-type SQR9, SQR9M1, and SQR9M2 cells were grown in MSgg medium at 37°C for the indicated times. This phenotype can be reversed by the addition of bacillomycin D. Pellicle formation assay results are shown for bacillomycin D-treated cells grown in MSgg in the absence or presence of 150 mM KCl. (B) OD570 of solubilized crystal violet from the microtiter plate assay over time for different mutant strains.

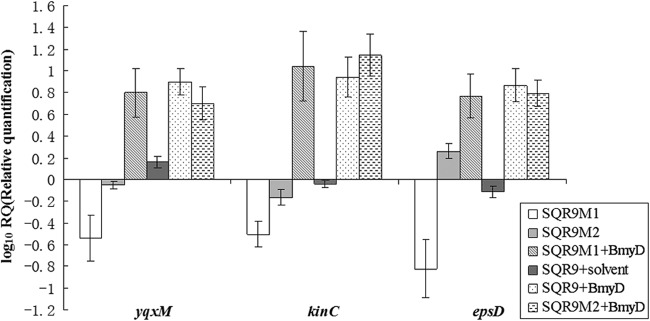

Genes involved in biofilm formation were regulated by bacillomycin D.

Transcription levels of three genes—epsD, yqxM, and kinC—in SQR9M1 and SQR9M2 relative to B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 were evaluated. The transcripts of epsD, yqxM, and kinC in SQR9M1 decreased significantly, with average expression levels decreased 7-, 3-, and 4-fold, respectively (Fig. 5). However, the transcripts of epsD, yqxM, and kinC in SQR9M2 showed no significant difference from B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9. The addition of bacillomycin D significantly increased the transcriptional levels of these three genes in SQR9M1 (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Transcriptional levels of yqxM, epsD, and kinC in the mutants SQR9M1 and SQR9M2 relative to wild-type B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9. evaluated by qRT-PCR. The experiments were carried out with pellicle obtained from microtiter plate when cells were grown in MSgg medium at 12 h. B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 recA gene was used as an internal reference gene. Bars represent standard deviations of three biological replicates. The solvent is 65% acetonitrile and 35% water with 0.1% acetic acid.

To investigate whether bacillomycin D induced B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 biofilm formation through the potassium leakage mechanism, as reported by Lopez et al. (25), biofilm formation by B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 and SQR9M1 plus bacillomycin D with addition of potassium chloride in the medium was recorded, and it was found that extracellular potassium chloride did not diminish the formation of biofilm (Fig. 4A and B). Transcription of kinC gene was not affected by extracellular potassium chloride addition, and several other salts (sodium chloride, potassium phosphate, and potassium acetate) had no effects on SQR9 biofilm formation and kinC gene transcription (data not shown). It seems that bacillomycin D induced SQR9 biofilm formation due to another reason instead of potassium leakage.

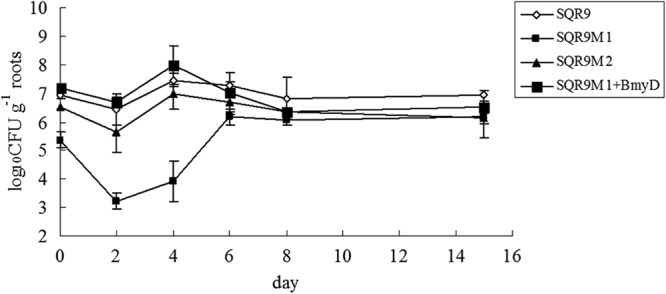

Bacillomycin D mutant decreased root colonization of cucumber seedlings.

To further test whether the B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 and its mutants differ in their ability to form biofilm on natural matrix surface, their colonization on roots of cucumber seedlings was monitored since B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 is a rhizosphere colonizer. On the second day after inoculation, approximately 106 CFU g−1 root of SQR9 were detected (Fig. 6), on the fourth day, the population on the root surface reached a peak value of 107 CFU g−1 root. After that, the bacterial population remained between ca. 106 and 107 g−1 root. Compared to SQR9, the population of SQR9M1 colonized on the root was significantly lower on second and fourth days; addition of bacillomycin D increased the colonization of SQR9M1 on root surface (Fig. 6). Root colonization of SQR9M2 was similar to strain SQR9. Because biofilm formation is a prerequisite for root colonization, these results confirmed that bacillomycin D was necessary for biofilm formation and has an effect on the root colonization.

Fig 6.

Populations of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9, SQR9M1, and SQR9M2 colonizing cucumber seedling roots. The data are expressed as log10 CFU per gram of fresh cucumber root.

DISCUSSION

Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens are well known for their biocontrol of fungal and bacterial diseases. The main mechanisms known to be involved in biocontrol include antibiosis, competition, growth promotion, and induction of systemically acquired resistance (14). Antibiotics are powerful weapons used by biocontrol strains to compete with other microorganisms (10). B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42, the well-studied biocontrol strain, devotes as much as 8.5% of its genome to the synthesis of antibiotics and siderophores (16). In a previous study, B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 exhibited efficient biocontrol activity against the pathogen Fusarium oxysporum, which is known to cause cucumber wilting (26). Bacillus-produced LPs are known to be responsible for the antifungal and the antibacterial activities of polyketides, and most bacillus strains used for biocontrol produce an array of LPs, which work synergistically or separately to antagonize fungal pathogens (10). In the present study, six lipopeptide fractions were detected in the cultures of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9. Biochemical and genetic approaches demonstrated bacillomycin D is the major compound responsible for the inhibition of F. oxysporum growth.

When bacillomycin D and fengycin synthesis pathways were individually disrupted, mutant SQR9M1, which was deficient in production of bacillomycin D, only showed minor antagonistic activity against F. oxysporum; however, the mutant SQR9M2, which was deficient in production of fengycin, showed antagonistic activity equivalent to that of the wild-type strain B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9. These experiments revealed that the bacillomycin D of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 plays a vital role in the antagonism against F. oxysporum. Moyne et al. (2) reported that bacillomycin D analogues produced by B. subtilis AU195 exhibit high inhibitory activity against A. flavus and a broad range of plant pathogenic fungi. Antibiotics in the iturin family were found to act upon sterols present in the cytoplasmic membrane of microorganisms. Furthermore, in B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42, a synergistic action of bacillomycin D and fengycin against the target microorganism has been demonstrated (12). However, in this study, bacillomycin D and fengycin did not exhibit synergistic actions against F. oxysporum.

It has been widely assumed that the ecological function of antibiotics in nature is fighting against competitors (24). However, more and more work had shown that antibiotics are not only bacterial weapons for fighting competitors but also signaling molecules that may regulate the homeostasis of microbial communities. It has been shown that concentrations of the aminoglycoside tobramycin below its MICs enhance the formation of bacterial biofilms (32). More specifically, several studies have shown that Bacillus LPs are crucially involved in biofilm formation. Lopez et al. (25) have shown that surfactin and potassium ion are important for motility of B. subtilis strain 6051. In this study, a bacillomycin D mutant was defective in biofilm formation and colonization on the plant root. However, addition of bacillomycin D restored this phenotype. The results from qRT-PCR analysis indicated that the bmyD-disrupted mutant significantly depressed transcription of the crucial genes involved in biofilm formation, e.g., epsD and yqxM, while the addition of bacillomycin D restored their transcription. In Bacillus strains, EPS and TasA were two major components of extracellular matrix which hold the differentiated cell chains together to form highly organized colony and pellicle architecture (33).

The epsA-O and yqxM-sipW-tasA operons are repressed by the master regulator SinR, which is antagonized by SinI (34). The sinI gene is transcribed only when the level of the phosphorylated transcription factor Spo0A∼P rises above a threshold level (35). Previous studies have demonstrated that KinC is a signal transduction protein that senses and responds to potassium leakage by phosphorylating Spo0A (25). Here, we also observed that addition of bacillomycin D could significantly increase the transcription level of kinC in MSgg medium. Then, the levels of Spo0A∼P are elevated, triggering the expression of other factors important in biofilm development. However, increasing the extracellular potassium concentration did not result in diminished biofilm formation, which indicates that KinC activation is not triggered by losing of potassium. Although the mechanistic role for bacillomycin D in biofilm formation remains to be determined, the delay of bacillomycin D-deficient mutants to establish surface-adherent populations in vitro and on plant surfaces suggests that bacillomycin D may play a role in surface attachment and survival in bacterial aggregations.

As a conclusion, the results reported here indicate that bacillomycin D plays not only a vital role in the antagonistic activity of B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9 against F. oxysporum but also contributes in biofilm formation. An important challenge for the future will be to determine exactly how KinC is activated by bacillomycin D.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 41271271) and the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2011BAD11B03). R.Z. and Q.S. were also supported by the 111 Project (B12009) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 November 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02645-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Minuto A, Spadaro D, Garibaldi A, Gullino ML. 2006. Control of soilborne pathogens of tomato using a commercial formulation of Streptomyces griseoviridis and solarization. Crop Prot. 25:468–475 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moyne AL, Shelby R, Cleveland TE, Tuzun S. 2001. Bacillomycin D: an iturin with antifungal activity against Aspergillus favus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 90:622–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ye SF, Yu Q, Peng YH, Zheng JH, Zou LY. 2004. Incidence of Fusarium wilt in Cucumis sativus L. is promoted by cinnamic acid, an autotoxin in root exudates. Plant Soil 263:143–150 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang S, Raa W, Yang X, Hu J, Huang Q, Xu Y, Liu X, Ran W, Shen Q. 2008. Control of Fusarium wilt disease of cucumber plants with the application of a bioorganic fertilizer. Biol. Fertil. Soils 44:1073–1080 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Romero D, Vicente A, Rakotoaly HR, Dufour ES, Veening JW, Arrebola E, Cazorla FM, Kuipers OP, Paquot M, Perez-Garcia A. 2007. The iturin and fengycin families of lipopeptides are key factors in antagonism of Bacillus subtilis toward Podosphaera fusca. Phytopathology 20:430–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qiu M, Zhang R, Xue C, Zhang S, Li S, Zhang N, Shen Q. 2012. Application of a novel bio-organic fertilizer can control Fusarium wilt by regulating the microbial community of cucumber rhizosphere soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 48:807–816 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Compant S, Duffy B, Nowak J, Clement C, Barka EA. 2005. Use of plant growth-promoting bacteria for biocontrol of plant diseases: principles, mechanisms of action, and future prospects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4951–4959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haas D, Keel C. 2003. Regulation of antibiotic production in root colonizing Pseudomonas spp. and relevance for biological control of plant disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41:117–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lugtenberg BJ, Kamilova F. 2009. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63:541–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ongena M, Jacques P. 2008. Bacillus lipopeptides: versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends Microbiol. 16:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kloepper WJ, Ryu CM, Zhang S. 2005. Induced systemic resistance and promotion of plant growth by Bacillus spp. Phytopathology 94:1259–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koumoutsi A, Chen XH, Henne A, Liesegang H, Hitzeroth G, Franke P, Vater J, Borriss R. 2004. Structural and functional characterization of gene clusters directing nonribosomal synthesis of bioactive cyclic lipopeptides in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain FZB42. J. Bacteriol. 186:1084–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Romero D, Perez-Garcia A, Rivera ME, Cazorla FM, de Vicente A. 2004. Isolation and evaluation of antagonistic bacteria toward the cucurbit powdery mildew fungus Podosphaera fusca. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64:263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raupach SG, Kloepper WJ. 1998. Mixtures of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria enhance biological control of multiple cucumber pathogens. Phytopathology 88:1158–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Szczech M, Shoda M. 2006. The effect of mode of application of Bacillus subtilis RB14-C on its efficacy as a biocontrol agent against Rhizoctonia solani. Phytopathology 154:370–377 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen XH, Koumoutsi A, Scholz R, Eisenreich A, Schneider K, Heinemeyer I, Morgenstern B, Voss B, Hess WR, Reva O, Junge H, Voigt B, Jungblut PR, Vater J, Sussmuth R, Liesegang H, Strittmatter A, Gottschalk G, Borriss R. 2007. Comparative analysis of the complete genome sequence of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:1007–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang N, Wu K, He X, Li S, Zhang Z, Shen B, Yang X, Zhang R, Huang Q, Shen Q. 2011. A new bioorganic fertilizer can effectively control banana wilt by strong colonization of Bacillus subtilis N11. Plant Soil 344:97 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davey ME, O'Toole GA. 2000. Microbial biofilms from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:847–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bais HP, Fall R, Vivanco JM. 2004. Biocontrol of Bacillus subtilis against infection of Arabidopsis roots by Pseudomonas syringae is facilitated by biofilm formation and surfactin production. Plant Physiol. 134:307–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramey BE, Koutsoudis M, von Bodman SB, Fuqua C. 2004. Biofilm formation in plant-microbe associations. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:602–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watnick IP, Kolter R. 1999. Steps in the development of a Vibrio cholerae El Tor biofilm. Mol. Microbiol. 34:586–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cazorla FM, Romero D, Perez-Garcia A, Lugtenberg BJ, Vicente A, Bloemberg G. 2007. Isolation and characterization of antagonistic Bacillus subtilis strains from the avocado rhizoplane displaying biocontrol activity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103:1950–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amellal N, Burtin G, Bartoli F, Heulin T. 1998. Colonization of wheat roots by an exopolysaccharide-producing Pantoea agglomerans strain and its effect on rhizosphere soil aggregation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3740–3747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Linares JF, Gustafsson I, Baquero F, Martinez JL. 2006. Antibiotics as intermicrobial signaling agents instead of weapons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:19484–19489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lopez D, Fischbach MA, Chu F, Losick R, Kolter R. 2009. Structurally diverse natural products that cause potassium leakage trigger multicellularity in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:280–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cao Y, Zhang Z, Ling N, Yuan Y, Zheng X, Shen B, Shen Q. 2011. Bacillus subtilis SQR9 can control Fusarium wilt in cucumber by colonizing plant roots. Biol. Fertil. Soils 47:495–506 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosado A, Duarte FG, Seldin L. 1994. Optimization of electroporation procedure to transform B. polymyxa SCE2 and other nitrogen-fixing Bacillus. J. Microbiol. Methods 19:1–11 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Landy M, Warren GH, Rosenman SB, Coli LG. 1948. Bacillomycin D, an antibiotic from Bacillus subtilis active against pathogenic fungi. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 67:539–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang J, Liu J, Wang X, Yao J, Yu Z. 2004. Application of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry in rapid typing of fengycin homologues produced by Bacillus subtilis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 39:98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Homon MA, Lazazera BA. 2001. The sporulation transcription factor Spo0A is required for biofilm development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1199–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoffman LR, D'Argenio DA, MacCoss MJ, Zhang Z, Jones RA, Miller SI. 2005. Aminoglycoside antibiotics induce bacterial biofilm formation. Nature 436:1171–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu J, Ma X, Wang Y, Liu F, Qiao J, Li XZ, Gao X, Zhou T. 2011. Depressed biofilm production in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens C06 causes gamma-polyglutamic acid (gamma-PGA) overproduction. Curr. Microbiol. 62:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kearns DB, Chu F, Branda SS, Kolter R, Losick R. 2005. A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 55:739–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fujita M, Gonzalez-Pastor JE, Losick R. 2005. High- and low-threshold genes in the Spo0A regulon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 187:1357–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.