Abstract

Xenopus laevis provides a number of advantages for studies on cardiovascular development. The embryos are fairly large, easy to obtain, and can develop at ambient temperature in simple buffer solutions. Although classic descriptions of heart development exist, the ability to use whole mount immunohistochemical methods and confocal microscopy may enhance the ability to understand both normal and experimentally perturbed cardiovascular development. We have started to examine the early stages of cardiac development in Xenopus, seeking to identify antibodies and fixatives that allow easy examination of the developing heart. We have used monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) raised against bovine cardiac troponin T and chicken tropomyosin to visualize cardiac muscle, a goat antibody recognizing bovine type VI collagen to stain the lining of vessels, and the JB3 mAb raised against chicken fibrillin which allows the visualization of a variety of cardiovascular tissues during early development. Results from embryonic stages 24–46 are presented.

Keywords: Xenopus, Heart Development, Confocal Microscopy

Introduction

Although some aspects of development are unique to a particular species, many features of developmental specification and organogenesis are shared. The frog, Xenopus laevis, has particular advantages for the study of organogenesis in general and cardiovascular development in particular. These aquatic frogs are easily maintained in the laboratory, and can be induced to lay eggs year round by hormonal stimulation. The fertilization and embryonic development is external, with the lineage of many tissues well established. In addition, the size of the egg and early embryo allow straightforward micromanipulation including microinjection and microdissection as a means to experimentally alter early development. Without providing an exhaustive listing of studies that impact on cardiovascular development, one can point to mRNA injection studies that have helped to elucidate the function of the genes Nkx2.3 and 2.5 (Cleaver et al., 1996; Evans et al., 1995; Grow and Krieg, 1998), PitX2 (Ryan et al., 1998), VEGF (Cleaver et al., 1997), Tbx5 (Horb and Thomsen, 1999) and Vg1 (Hyatt and Yost, 1998). The analysis of cardiac specific promoters, like cardiac actin (Taylor et al., 1989)and expression studies using dominant negative proteins (Fu et al., 1998; Grow and Krieg, 1998) have also been carried out in developing tadpoles.

Although the simple visual inspection of the heart can provide information on size or whether it looped to the right or left, the assessment of internal changes in the cardiac valves or septa requires a more invasive analysis. The interpretation of changes due to experimental manipulation requires a clear understanding of what a normal heart looks like at specific stages of development and some idea of when different structures normally form. Although sectioned material can reveal perturbations in the developmental pattern, this approach is tedious and requires an intimate familiarity with the normal pattern as seen in a two dimensional plane.

The need for generally accepted baseline information lead Nieuwkoop and Faber and more than 20 collaborating scientists to compile the "Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin)". These authors provided a narrative of overall development and drawings of whole embryos at each developmental stage from fertilization until about two months later when the embryo has progressed into a small frog (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967). A complementary work by Hausen and Riebesell, "The early development of Xenopus laevis" provides a very useful histological account of early development but stops at the stage when the actual morphological differentiation of the heart starts (Hausen and Riebesell, 1991). Here we use whole mount immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy to visualize the developing frog heart. We have concentrated on stages where the first expression of cardiac muscle can be detected through the development of cardiac valves and septa about 5 days later. Our aim was to identify fixation procedures that, coupled with readily available antibodies would allow a dynamic view of the normal formation of the early heart and thus provide a "standard template" for the comparison of abnormal hearts.

Materials and Methods

Animals: Xenopus laevis were purchased from Xenopus I (Ann Arbor MI). Females were induced to lay eggs by injection with 200 units of Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis MO) at least three days prior to injection with Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (500–1000 units, Sigma Chemical, St. Louis MO). Eggs were collected in egg laying buffer (100mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 0.2 mM MgSO4,0.4 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Tris (pH 7.6)) to prevent the swelling of the jelly coat. Testes were removed from male frogs that had been euthanized with 1 ml of a 10mg/ml solution of tricane (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis MO). A small piece of testes was crushed in 0.1 MMR (1X MMR= 100mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)) and added to the eggs after nearly all the egg laying buffer was removed from the eggs. The egg/sperm mix was flooded with water and the embryos were allowed to develop at room temperature. Embryonic stages were identified by the criteria describe in Nieuwkoop and Faber (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967).

Fixation and immunohistochemistry: Tadpoles were fixed in Dent's fixative (80% methanol, 20% dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) and stored at −20°C until processed. Except where noted, subsequent treatments and rinses were carried out on samples in 24-well plates on an orbital shaker. In cases where embryos younger than stage 40 were heavily pigmented, samples were bleached prior to addition of antibodies. Bleaching was carried out using 5% hydrogen peroxide (in Dent's fixative) in clear glass vials rotating in bright light for 4–5 hours, then returned to Dent's and either stored at −20°C or further processed. Prior to immunolabeling the ventral dermal layer overlying the hearts of stage 44 and 46 tadpoles was manually removed to help antibody penetration and ensure optimal imaging of the hearts.

Embryos were rehydrated to PBS in a methanol-PBS series which included 1% DMSO at each step. Embryos were then treated with bovine testicular hyaluronidase (1mg/ml in 50mM acetate buffer), 30–45 min at room temperature, rinsed in PBS-TD (PBS, 1% Tween-20, 1% DMSO, 0.02% NaN3) and blocked for 4 hrs at room temperature or overnight at 4°C in block solution ( PBS-TD containing 0.1 M glycine, 2% powdered milk, and 5% serum from the host species of the secondary Ab or 1% BSA). Primary antibodies were diluted with block solution as follows: goat anti-bovine type VI collagen (Southern Biotechnology Associates) - 1:50, mouse anti-bovine cardiac troponin T (CT3, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), U. of Iowa) -1:10, mouse anti-chicken tropomyosin (CH1, DSHB) - 1:50, mouse anti-chicken fibrillin (JB3, gift from Dr. Charlie Little, Medical University of South Carolina) - 1:50. Incubation with primary antibody was carried out overnight at 4°C. Samples were then rinsed 6–8 times over 8–10 hrs with PBS-TD. Secondary antibodies were used as follows: anti-goat conjugated to Alexa 488, anti- mouse conjugated to Alexa 568 (both from Molecular Probes), anti-goat conjugated to Cy5, anti-mouse conjugated to Cy5 (both from Jackson ImmunoResearch). All were diluted 1:200 in blocking solution and allowed to incubate with the sample overnight at 4°C. Samples were rinsed as described for primary antibody treatment and subsequently dehydrated in an ethanol series.

Double labeling with anti-fibrillin (JB3) and either anti-troponin (CT3) or anti-tropomyosin (CH1) required a more elaborate procedure as all three antibodies were raised in mouse. Using the same solutions and dilutions for rinsing, blocking, and antibody incubation as described above, the double labeling was carried out according to procedures described by Jackson ImmuoResearch. Samples were incubated with CT3 or CH1 (we found that using the antibodies made against muscle first was much more effective than starting with JB3) and then rinsed 6–8 times over 8–10 hrs with PBS-TD. Samples were then incubated overnight with rabbit anti-mouse conjugated to Cy5 (we found that using the Cy5 conjugate to detect the muscle worked better for early embryos than the Alexa 568 conjugate). Samples were rinsed 6–8 times over 8–10 hrs with PBS-TD and then incubated with 5% heat inactivated normal mouse serum (heat inactivated at 60°C for 30 min) for 4 hrs at room temperature followed by rinsing 3X over 3hrs. Samples were then incubated in unconjugated rabbit anti-mouse Fab (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 0.025 mg/ml) diluted in blocking solution, overnight at 4°C and subsequently rinsed 6–8 times over 8–10 hrs with PBS-TD. Samples were then incubated with JB3 overnight, and rinsed 6–8 times over 8–10 hrs with PBS-TD. Samples were then incubated overnight with rabbit anti-mouse conjugated to Alexa 568. Samples were rinsed as described for primary antibody treatment and subsequently dehydrated in an ethanol series.

A western blot of homogenized, sonicated stage 35 embryonic tissue was performed. 20 micrograms of pellet or supernatant protein (after a 10,000 rpm, 10 min centrifugation using a Hermle microcentrifuge ) were loaded under reducing conditions onto a precast 4–15% polyacrylamide mini-gel (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated by electrophoresis and then transferred onto Protran (Schleicher & Schuell) or Immobilon-P (Millipore). Membranes were blocked 1 hr in TBS-T (tris-buffered saline containing 0.5% Tween-20) containing 5% dry milk. The membranes were then incubated in primary antibodies diluted in block as follows: CH1 = 1:500, CT3 = 1:100, JB3 = 1:250. Blots were then rinsed in TBS-T containing 1% milk, and then incubated in secondary antibody, peroxidase conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) 1:10,000 in block. Membranes were then rinsed in TBS-T. ECL (Pierce) was then carried out. Only the CH1 antibody showed strong reactivity to a protein of approximately 38 kDa. Thus, immunohistochemical reactivity cannot be directly correlated with the effective use of these antibodies for western blot analysis for Xenopus proteins.

Embryos were mounted for viewing in "mounting wells" constructed by filling the depressions of concave slides with sylgard 184 silicone elastomer (Dow Corning) working solution, and allowing polymerization at 55°C overnight. Wells to accommodate the embryos were carved out of the elastomer with a scalpel. Prior to mounting specimens younger than stage 35, the caudal half of the embryo was removed (we empirically found better imaging when this dissection was performed). Embryos were positioned in the mounting wells and excess EtOH was removed. The specimens were held down with forceps as the clearing agent, BABB (benzyl alcohol: benzyl benzoate, 1:2, adjusted to pH 7.0) was added since the embryos became buoyant in the dense BABB and were difficult to reposition after clearing. The pH of the BABB used, was routinely brought near neutral by stirring it in the presence of NaOH pellets. Embryos were covered with a coverslip and viewed on a Nikon optiphot/Bio-Rad MRC-1024 confocal microscope equipped with a krypton/argon laser. Images were initially saved at a resolution of 1024×1024 pixels/inch. In some cases the resolution was reduced to accommodate memory capacity of computers and/or printers. Confocal Assistant 4.02 and Adobe Photoshop 5.0 were used for image processing.

Results

Antibodies recognizing structural proteins of cardiac muscle provide an overview of myocardial development

In Nieuwkoop and Faber (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967) the initial development of the heart is described as follows, "two presumptive heart anlagen, located in the anterior, latero-ventral mesoderm at stage 15, begin to fuse at stage 16…a single median presumptive heart anlage is not established before stage 19…becomes more sharply delimited during the following stages the actual differentiation of the heart anlage only starts at about stage 27." (about 31 hours after fertilization of the egg). We assumed that the expression of muscle proteins would provide a recognizable hallmark of early heart differentiation. In addition, the conservation of muscle proteins among species made it likely that antibodies raised against chicken tropomyosin (CH1) or bovine cardiac troponin T (CT3) would recognize the same proteins in frogs.

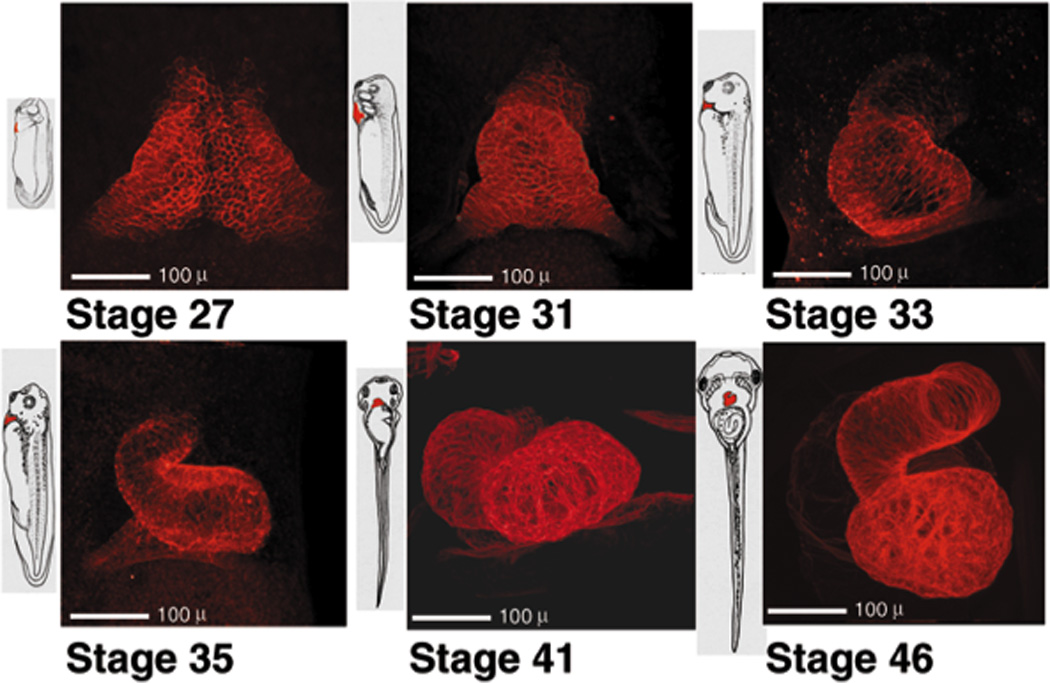

When we examined stage 27 using Ab directed against tropomyosin (Fig. 1), populations of cells from both sides of the ventral midline were easily recognized, forming a delta shaped region most narrow in the anterior region of the embryo. By stage 31, (about 38 hours post fertilization, Fig. 1) the posterior region of myocardium bulges ventrally and the triangular shape of the field is less broad at its posterior base. By stage 33/34 (about 42 hours after fertilization) the heart has started to twist, resulting in the S shaped structure seen in stage 35 (50 hours post fertilization). By stage 41(76 hours post fertilization) the myocardial staining of both the ventricle and the truncus show that these structures have thickened. By stage 46 (106 hours post fertilization) enough time has passed for the atria to have formed. The ventral view of the heart allowed the easy observation of both ventricle and outflow tract. The micrographs of the hearts in Fig. 1, along with the embryos as depicted by Nieuwkoop and Faber (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967) provide a view of the progressive formation of heart from the perspective of the myocardium.

Figure 1.

Cardiac muscle development in Xenopus. (Right subset) Confocal images of the heart regions of six stages of embryos (27 – 46) are presented (ventral views), each adjacent to a diagrammatic representation of an embryo (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967) at the corresponding stage. Prior to microscopy, stage 27 – 33 embryos were immunolabeled with anti-tropomyosin (CH1) and stages 35 – 46 with anti-cardiac troponin T (CT3). The secondary antibody used for all stages was conjugated to Cy5. Each confocal image represents a digitally colored compilation of 30 – 53 optical sections taken (in grayscale) five – seven microns apart. All confocal images were taken at the same magnification and are presented with the anterior of the embryo at the top of the Figure. Scale bar = 100 microns.

Non-myocardial cell participation in heart development can be visualized using JB3 antibody

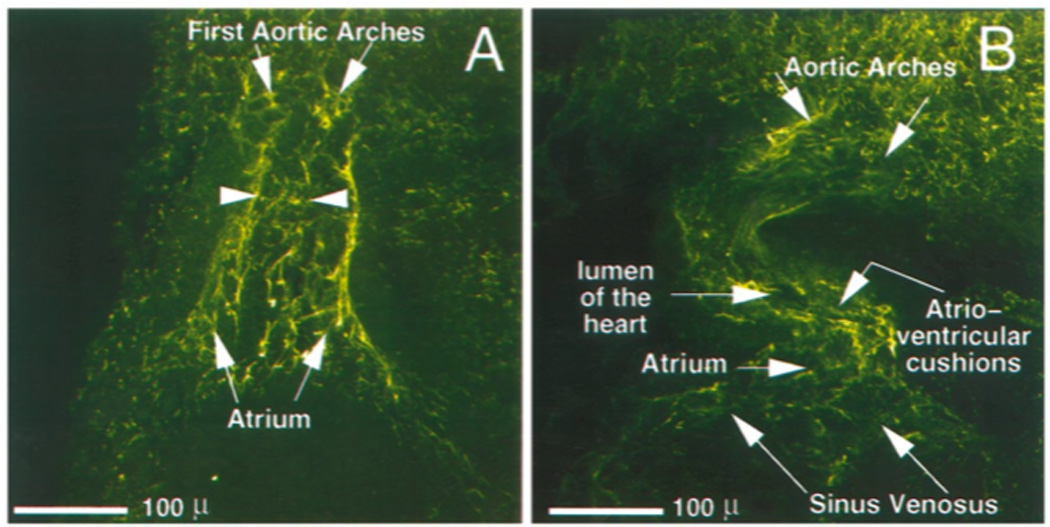

We have not yet identified an antibody that can be used in all developmental stages to identify the endothelium in the heart. However, the Ab JB3 (anti-fibrillin) allows a view of the heart field that differs from that seen with the antibodies that stain the myocardium. Fibrillin is one of the proteins that has been identified in the extracellular matrix, especially in the microfibrils that are associated with elastic tissues and basement membranes (Sakai et al., 1986). Several studies have shown that fibrillin can be seen along the anterior-posterior axis of chick embryos as the notochord forms. Fibrillin is also found in association with a subpopulation of cardiac endothelial cells and the mesenchyme and mesenchymal derivatives that form the valves and septa of the heart (Gallagher et al., 1993; Hurle et al., 1994; Wunsch et al., 1994). With these findings in mind we tested frog embryos for reactivity with JB3. It is important to note here that we have not established that Xenopus fibrillin is the protein recognized, although that is the simplest interpretation of the data. In the stage 27 heart (Fig. 2A) JB3 outlines cells in a much narrower region than what was seen using the muscle markers. In the view presented (Fig. 2A), the staining seen is consistent with the description of endocardial tube formation in Nieuwkoop and Faber (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967) which states" At stage 28 the endocardial tube appears as a condensation of cell material with the beginning of a central dilatation. We interpret the staining in Fig. 2A as the secretion of JB3 reactive antigen into the mesocardial space between the muscle and the endocardial precursors. At this stage (in contrast to data shown for stage 28 in Fig. 3) the endocardial lumen has not yet formed. Later, by stage 35 (Fig. 2B), the staining pattern outlines the endocardial tube allowing the identification of the atrioventricular cushions and emphasizing the bending of the heart at this stage.

Figure 2.

Non-muscle cardiac development in Xenopus. Images represent the cardiac regions of embryos (stage 27 and stage 35) immunostained with anti fibrillin (JB3). The secondary antibody was conjugated to Alexa 568. Ventral views of the heart regions of embryos are presented with the anterior of the embryo at the top of the Figure. The stage 27(A) and stage 35 (B) images were formed by the digital merging of 28 and 36 optical sections four and five microns apart, respectively (taken in grayscale) and digitally colored. At stage 27, the endocardial tube is not completely formed. The unlabeled arrows point to unpartitioned secreted material at the embryos midline. By stage 35 (B), a single heart tube has formed into a "S" shape; the sinus venosus is paired. Scale bar = 100 microns.

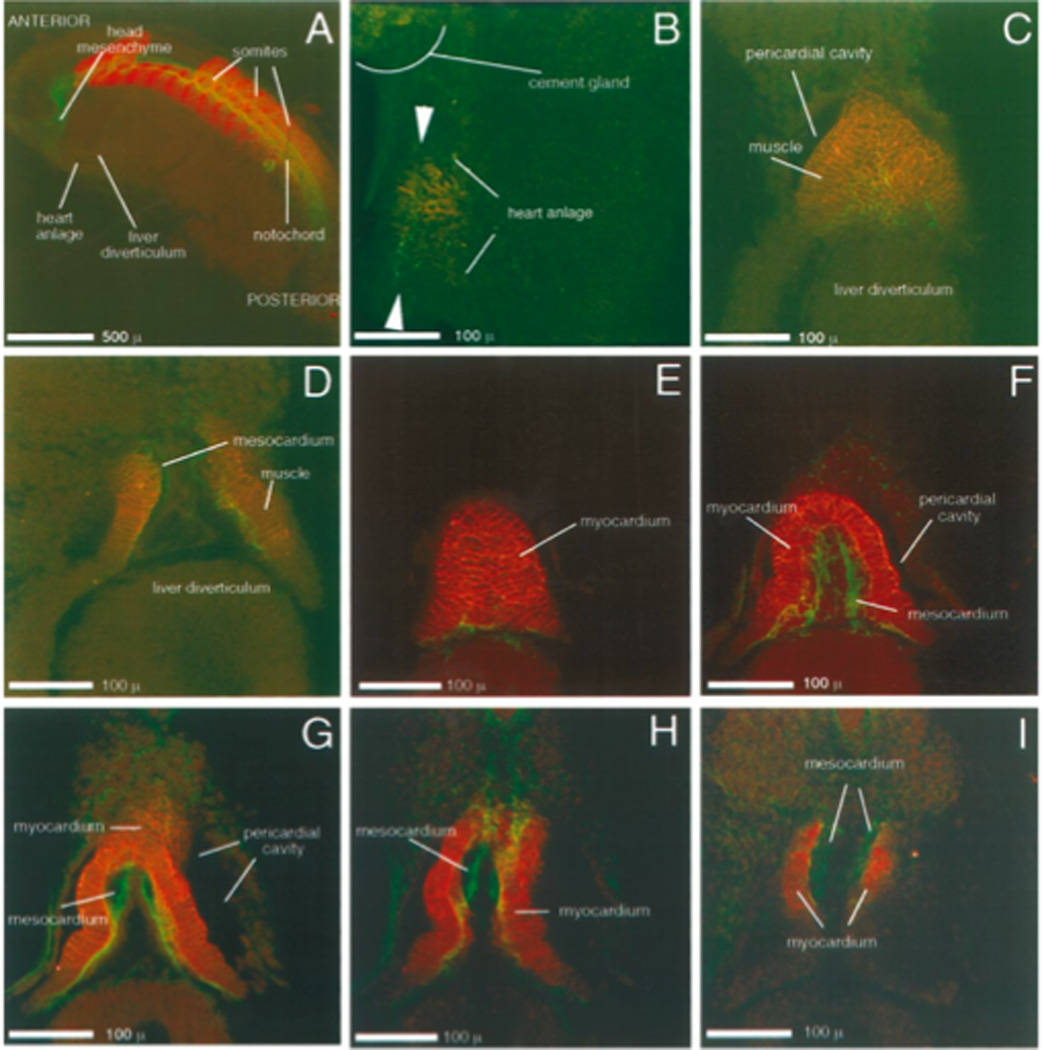

Figure 3.

“Milestones” of early cardiac development in Xenopus visualized by confocal images of double immunostained embryos. Embryos selected to represent a chronology of stages were double labeled with anti-tropomyosin (CH1) = red and anti fibrillin (JB3) = green and optically sectioned. For each stage, the set of optical sections (28 to 40 sections, four to six microns thick) were digitally compiled in increments of four to six sections. Resulting optical thick sections that aid in the visualization of Xenopus heart development are presented. The order of presentation for stages with more than one image is ventral to dorsal. Image A is a parasagittal view of a stage 24 hemi-sectioned embryo. The stage 26 embryo in B is shown from the left lateral view. Images of stages 28 (C and D) and 31 (E-I) are ventral views of heart regions with the anterior of the embryos placed at the top of the Figure. At stage 24, the heart analage is present but not immunohistochemically active. By stage 26, the first presence of antibody reactivity is noted near the ventral midline (ventral midline lies between arrowheads). At stage 28 (C and D), differentiation of the heart analage is clear; the pericardial cavity can be discerned. Stage 31 (E–I) - the heart region extends ventrally beyond the pericardial cavity and is slightly bent laterally to the embryo's right; the myocardial wall does not yet close. Scale bars as denoted.

Double staining of whole mount embryos provides a more complete picture of cardiac development

Embryos were simultaneously stained with JB3 and antibodies that recognize muscle to better understand the onset of differentiation, the position of the endocardial tube within the developing myocardium and the formation of the valves and septa. In Figures 3 and 4 selected optical sections of stages 24, 26, 28, 31,35, 41 and 44 are presented with the location of JB3 reactive material shown in green and tissue reacting with CT3 or CH1 in red. Identification of structures in the micrographs was based upon descriptions from Hausen and Riebesell (Hausen and Riebesell, 1991) for stages 24, 26 and 28 and on Nieuwkoop and Faber (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967)for all stages. In stage 24 (Fig. 3A), a parasagittal section of an embryo is shown. At this stage the heart anlage is present, but not strongly reactive with either antibody. However, the head mesenchyme and notochord are reactive to JB3 and there is strong somitic staining using CH1 (anti-tropomyosin). The JB3 staining at this stage is reminiscent of that previously reported in quail where prominent staining was present around (Rongish et al., 1998) the somites demarcating the notochord. We detected staining in the presumptive heart region by stage 26 (left lateral ventral view Fig. 3B), slightly earlier than expected. If examined from a ventral view, the stained region appears much less triangular than in stage 27 (Fig. 1) and less intense, signifying lower levels of antigen. Both antigens are most evident in cells nearest to the midline with JB3 confined to a narrower region.

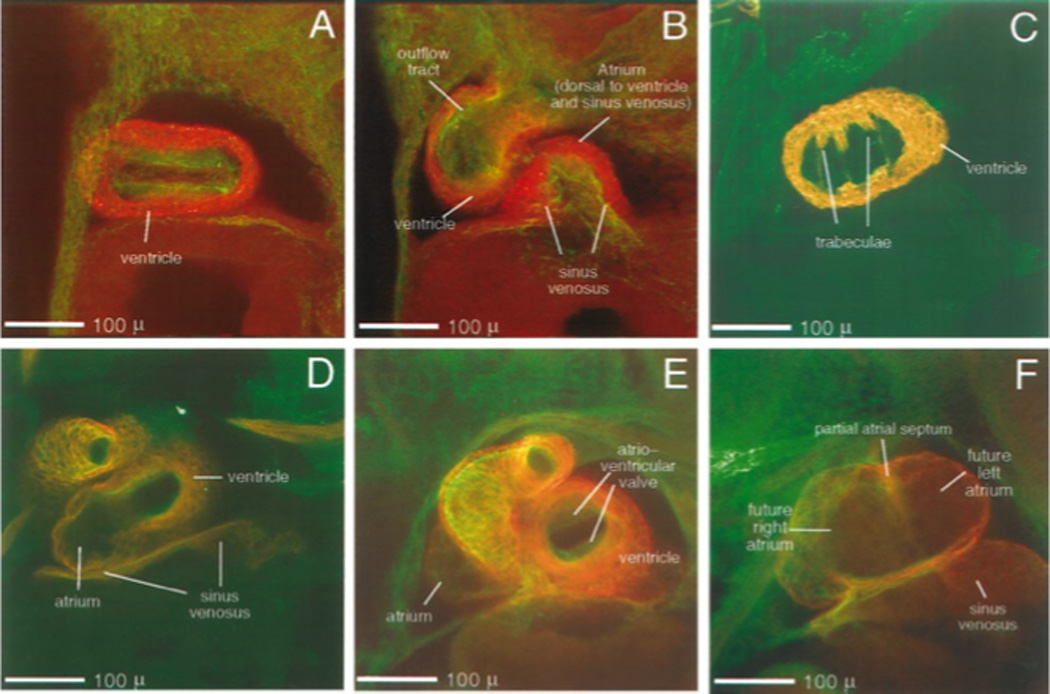

Figure 4.

“Milestones” of early cardiac development in Xenopus (continued). Embryos were double labeled with anti-cardiac troponin T (CT3) = red and anti-fibrillin (JB3) = green and optically sectioned. For each stage, the set of optical sections (35 to 53 sections five to seven microns thick) were digitally compiled in increments of six to nine sections. Resulting ventral views of optical thick sections are presented. By stage 35 (A and B) the myocardial wall is closed and the heart tube has become twisted in a "S" shape; the chambers are now distinct. Stage 41 (C and D)- the myocardium thickens and develops trabeculae; the atrium is posterior to the ventricle. At stage 44 (E and F) the single atrium begins to be partitioned by the forming septum and is pushed slightly anterior to the ventricle. Scale bar = 100 microns.

By stage 28 (Fig. 3C and D), myocardial staining is easily seen with JB3 reactive material enclosed within the field of myocardial tissue. At this point the myocardial tissue does not join dorsally to form a tube although the development towards a tubular shape is apparent. In Fig. 3D, JB3 staining is concentrated in two regions that run along the anterior to posterior axis of the heart next to the myocardial staining suggesting that the lumen of the endocardial tube has formed. By stage 31 (Fig. 3E–I) most of the myocardial region of the heart is still a trough rather than a tube as the dorsal portion of the myocardial wall is still unfused. The first hint of myocardial tube closure comes at the posterior end of the heart. The heart tube is slightly bent, laterally to the right side of the embryo. In micrographs not presented one can see that the myocardial wall completes closure by stage 33. The "S" shaped heart tube characteristic for embryos of many species occurs in frog hearts by stage 35 (Fig. 4A, and B). This stage also marks the movement of the atrial region of the heart to a more anterior and dorsal position in the embryo. At stage 41 (Fig. 4C and D) the ventricular myocardium is thickened and trabeculation commences. The micrographs of stage 44 (Fig. 4E and F) highlight the forming atrioventricular valve and the start of septation of the atria. At stage 44 the difference in myocardial thickness between the thicker ventricle and the thinner atria is easily seen.

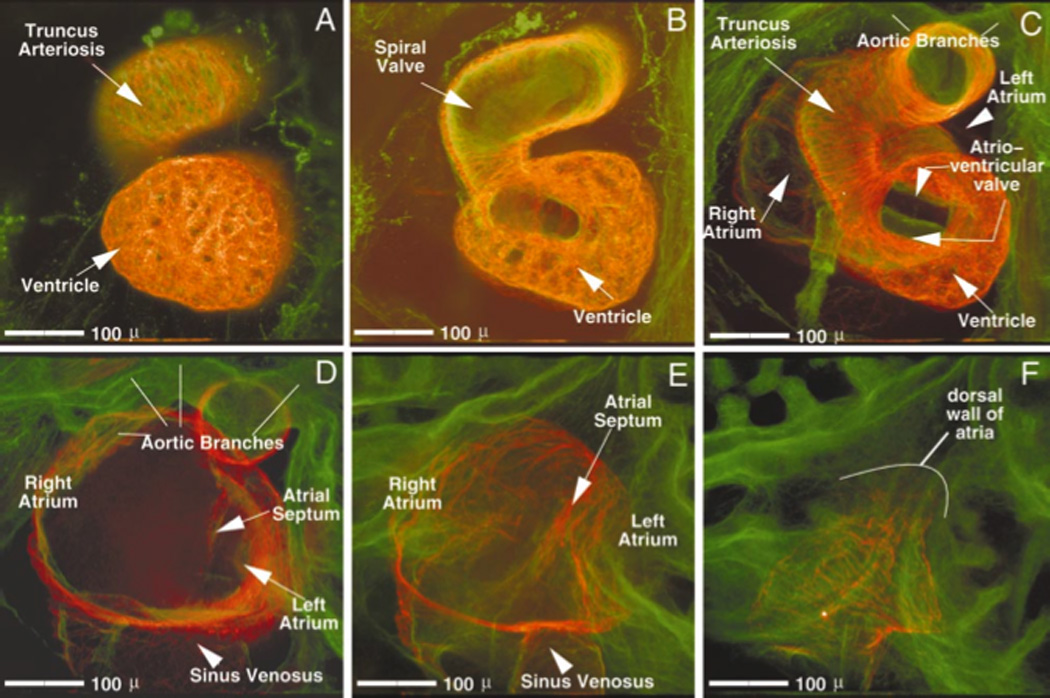

By stage 46 (Fig. 5A–F) the embryonic heart has most of the structures found in adult heart (U.Tajchman unpub.; (Deuchar, 1975; Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967)). Starting on the ventral side of the embryo, optical sectioning through the double-stained heart highlights the muscular ventricle and the presence of a spiral valve in the truncus arteriosus (Fig. 5 A and B). Progressing through the heart the atrioventricular valve (Fig. 5C), the two atria, and the atrial septum sequentially come into view (Fig. 5D–F).

Figure 5.

Ventral to dorsal progression through a stage 46 Xenopus heart. Images were digitally created from a series of 48 optical sections (taken five microns apart) through a double labeled stage 46 Xenopus heart (red = CT3; green = JB3). Image A represents the most ventral eight images of this series, digitally merged; image B, the next eight, etc. The relative positioning of heart structures to one another, as well as an individual structure’s order of emergence within the series can be established: the truncus arteriosis and ventricle are always most ventral (A). Progressing dorsally, the spiral valve (B) appears within the truncus. Next, the single atrioventricular valve (C) is seen overlying the atrial septum (D and E). Midway through the series (C and D), the first views of the atria, as well as the aortic branches are viewed. Both atria and the sinus venosus are seen more dorsally (D and E). Finally, the back wall of the atria is seen, positioned most dorsal (F). Scale bar = 100 microns.

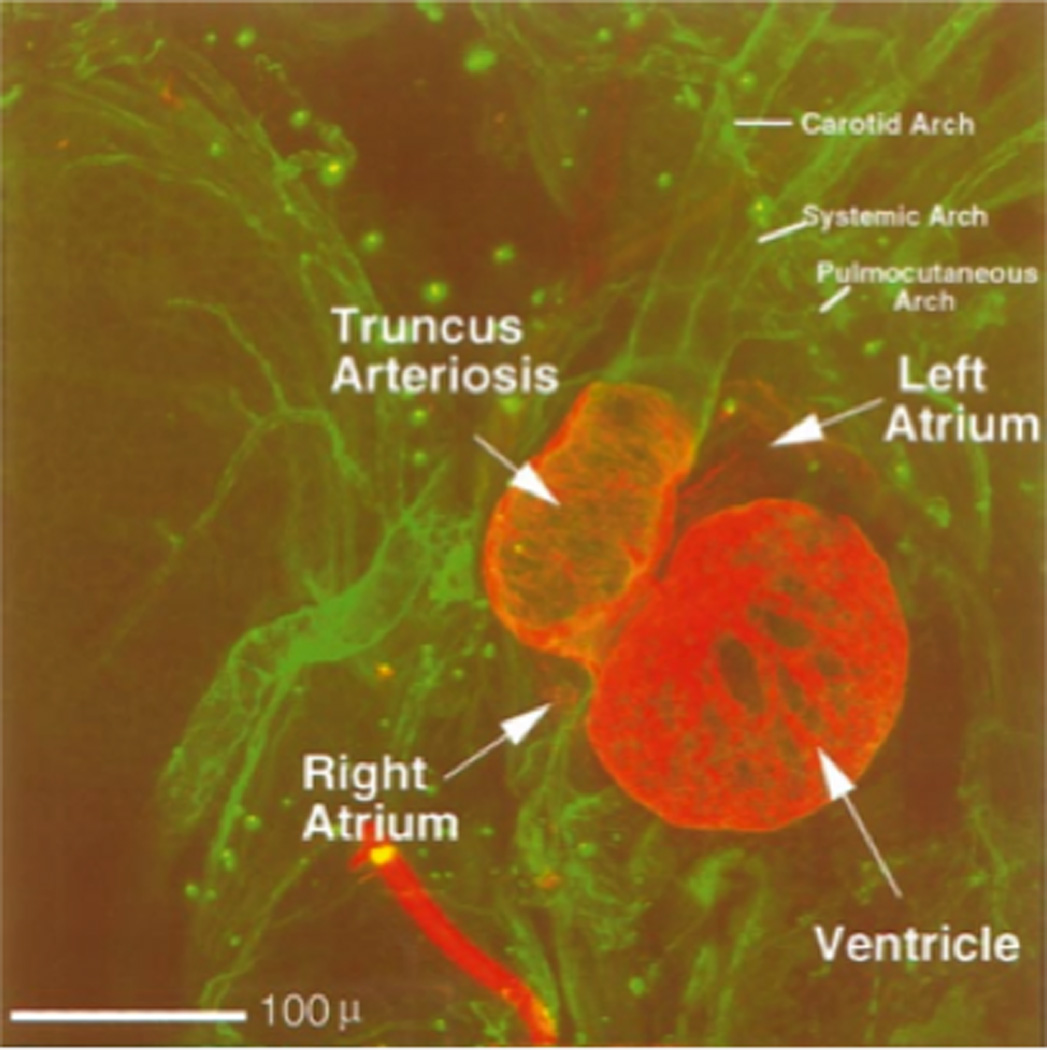

The vasculature system surrounding the heart is easily viewed by co-staining using anti-troponin and anti-type VI collagen (Fig. 6). The truncus splits into paired aortic arches that further branch three times to form the carotid, systemic and pulmocutaneous arches. In this ventral view the right set of arches is partially obscured by the truncus arteriosis.

Figure 6.

Early vasculature in Xenopus. Ventral view of a double-labeled stage 46 Xenopus embryo (red = anti-cardiac troponin T (CT3); green = anti-type VI collagen). Image represents 45 optical sections through the embryo, each ten microns thick, digitally merged and colored. The first three branches on the left side of the paired aortic arches are easily distinguished with the antibody to type VI collagen, as are all chambers and the truncus arterisos with the antibody to cardiac troponin T. Scale bar = 100 microns

Discussion

Since Nieuwkoop and Faber and their collaborators painstakingly described the embryogenesis of Xenopus in 1956 a variety of technological advances have been made with respect to the ability to visualize embryonic development. The combined efforts of a large number of investigators have refined the use of immunohistology and whole mount fixation techniques (Harland, 1991; Klymkowsky and Hanken, 1991). Advances in computational capacity, together with confocal microscopy, provide a means to capture digital information. This data can be viewed as single thin sections or stacked into a three dimensional view of the developing frog heart.

The identification of gene products that are implicated in proper cardiovascular development has also accelerated (Harvey et al., 1997). As the functions of these genes are investigated, it is critical that the endpoint of the analysis becomes more than the appearance or disapperance of bands on an agarose gel. The consequence on normal structure must also be examined. Thus, clear and reproducible images of structure need to be accessible for comparative interpretation of data.

With this in mind we have sought to optimize techniques that provide a straightforward look at the development of the frog heart. For the antibodies used in this paper both paraformaldehyde based (Harland, 1991) and DMSO/methanol (Klymkowsky and Hanken, 1991) tissue fixatives were tried. Far better results were found using DMSO/methanol. While other antibodies may give optimal results with other fixatives we observed that paraformaldehyde fixed embryos tended to have higher non-specific background fluorescence. Many chromofluors are pH sensitive and for the studies described here we noted that the clearing agent BABB has a relatively acidic pH. We routinely brought the pH to near neutral by the stirring the BABB in the presence of NaOH pellets until the solution was about pH 7. In some stages, to assist penetration of reagents and also simplify confocal analysis of the heart, we physically removed ventral dermis, or the dorsal half of the embryo.

For the examination of myocardial development, we used two antibodies, CH1 and CT3, available through the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. Although neither was originally raised against frog protein, they provide consistent and strong staining of muscle tissues in the embryos. Using these antibodies, myocardial field establishment, tube closure, development of the outflow tract, atria and ventricle are all readily imaged. In addition, we were able to detect differentiation, indicated by the expression of muscle proteins, slightly earlier than was possible by visual inspection of the embryo (stage 27 was the onset of differentiation reported in (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967)). We found that in stage 26 the region of staining was oval, centered, and concentrated on the ventral midline. This contrasts with the triangular region of staining seen by stage 27 (Fig. 1), and with in situ detection shown by others of several muscle mRNAs. In situ studies indicate that two distinct lateral regions of gene expression bracket the ventral midline (for in situ data see (Cleaver et al., 1996; Drysdale et al., 1994)). We note that heart muscle mRNA in these distinct lateral fields can be detected in stages prior to our ability to see protein (P. Krieg, personal communication). Future studies with other antibodies may be informative concerning the progression from muscle gene activation to production of muscle protein.

By using the anti-fibrillin antibody JB3 the formation of the endocardium can be viewed via its secretion of the JB3 epitope into the extracellular matrix that lies between the myocardium and the endocardium. Specific epitope detection results in slightly lower apparent resolution when viewed in contrast to what was seen with CH1 or CT3, which would be expected for a secreted molecule. However, as early as we could detect myocardial staining we also detected JB3 epitope staining. JB3 staining began as a mass in the heart forming region and by stage 28 was displayed in a manner consistent with its secretion between the endocardium and myocardium, and not into the lumen of the endocardial tube. Fortuitously, we found that when we used a high concentration of the JB3 Ab, non-specific background staining increased the ability to view many heart structures including myocardial and endocardial tissues and the valves and septa of the heart.

Being able to recognize normal and altered cardiac development in Xenopus will allow both the similarities and differences between Xenopus and other organisms to be used to best advantage. There are clear differences in the details of cardiac development when Xenopus is compared to mammals. For instance, although paired lateral primordia are present in both systems, in Xenopus these primordia meet at the anterior ventral midline prior to the formation of either endocardial or myocardial tubes. Thus, the fusion events that form the hearts of amniotes are not identical to that seen in Xenopus, although the outcome is very similar. Ultimately, Xenopus hearts have only three chambers with a single ventricle while mammals have four chambers. In addition the truncus arteriosus in the frog does not divide into the aorta and pulmonary artery but separates blood flow by a spiral valve. The spiral valve (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967) is remarkably like the aorticopulmonary septum that can be seen in a 6 week human heart (Sadler, 1990) and its persistence throughout development may serve as a model for defects involving persistent truncus arteriousis.

Many features that were seen by confocal imaging of Xenopus laevis hearts have a direct correlate in mammalian heart development. Characteristic asymmetries are common to Xenopus and mammalian hearts, including the leftward bend of the outflow tract, and the division of the early atrium into right and left side (with the right side being larger) by the formation of an atrial septum. The control and restriction of blood flow between the atria and ventricle is accomplished by the atrioventricular valve. In both frog and mammal the musculature of the ventricle is thicker than that found in the atrium, and includes the development of trabeculae. The similarity continues at the molecular level with the strong conservation of both regulatory factors and the expression of structural proteins of cardiovascular development.

We believe that both the similarities and differences should prove useful in studies that aim at understanding heart formation and congenital heart defects. The ability to view the overall changes that accompany cardiogenesis using confocal microscopy enhances the ability to understand the function of gene products involved in proper cardiovascular development.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognize the assistance of the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facility and Chip Geaves for technical help. We also thank Dr. Charlie Little for helpful comments and for the generous supply of the JB3 antibody. Drs. Greg Kitten, Jackie Brittingham and John Dagle and Paul Krieg provided helpful comments. CH1 and CT3 antibodies, developed by Dr. Jim Lin, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, and Iowa City, IA 52242 City. We also thank Ms A. Chou (Garland Publishing) and Dr. J.G. Bluemink (Hubrecht Laboratory) for permission to use Figures from Nieuwkoop and Faber. U.T. was supported by a NIH Pediatric Cardiology Fellowship. This research was supported by HL42252 (DLW).

Contributor Information

Sandra J. Kolker, Department of Biochemistry, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242

Urszula Tajchman, Department of Pediatrics, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242.

Daniel L. Weeks, Department of Biochemistry, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242

References

- Cleaver O, Tonissen KF, Saha MS, Krieg PA. Neovascularization of the Xenopus embryo. Dev. Dyn. 1997;210:66–77. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199709)210:1<66::AID-AJA7>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver OD, Patterson KD, Krieg PA. Overexpression of the tinman- related genes XNkx-2.5 and XNkx-2.3 in Xenopus embryos results in myocardial hyperplasia. Development. 1996;122:3549–3556. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar E. Xenopus: The South African Clawed Frog. London: John Wiley and Sons; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale TA, Tonissen KF, Patterson KD, Crawford MJ, Krieg PA. Cardiac troponin I is a heart-specific marker in the Xenopus embryo: expression during abnormal heart morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1994;165:432–441. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Yan W, Murillo MP, Ponce J, Papalopulu N. tinman, a Drosophila homeobox gene required for heart and visceral mesoderm specification, may be represented by a family of gene in vertebrates:XNkx-2.3, a second vertebrate homolgue of tinman. Development. 1995;121:3889–3899. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Yan W, Mohun T, Evans S. Vertebrate tinman Homologues aer required for formation of the differentiated heart and are functionaly redundant. Development. 1998;125:4439–4449. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher B, Sakai L, Little CD. Fibrillin delineates the primary axisin the early avian embryo. Developmental Dynamics. 1993;196:70–78. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001960109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow MW, Krieg PA. Tinman function is essential for vertebrate heart development: Elimination of cardiac differentiation by dominant inhibitory mutants of the tinman-related genes, XNkx2-3 and XNkx2-5. Developmental Biology. 1998;204:187–196. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland RM. In situ Hybridization: An improved Whole Mount Method for Xenopus embryos. In: Kay B, Peng B, editors. Methods in Cell Biology. Vol. 36. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RP, Olson EN, Schulz RA, Altman JS. Human Frontier Science Program Workshop. Strasbourg: 1997. Genetic Control of Heart Development. [Google Scholar]

- Hausen P, Riebesell M. The early development of Xenopus laevis: An Atlas of the Histology. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Horb ME, Thomsen GH. Tbx5 is essential for heart development. Development. 1999;126:1739–1751. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurle JM, Kitten GT, Sakai LY, Volpin D, Solursh M. Elastic Extracellular Matrix of the Embryonic Chick Heart: An Immunohistological Study using Laser Confocal Microscopy. Developmental Biology. 1994;200:321–332. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt BA, Yost HJ. The left-right coordinator: The role of Vg1 in organizing left-right axis formation. Cell. 1998;93:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymkowsky MW, Hanken J. Whole-Mount Staining of Xenopus and Other Vertebrates. In: Kay B, Peng B, editors. Methods in Cell Biology. Vol. 36. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 420–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin) Amsterdam: North Holland publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Rongish BJ, Drake CJ, Argraves WS, Little CD. Identification of developmetal marker, JB3-antigen as fibrillin-2 and its de novo organization into embryonic microfibrous arrays. Developmental Dynamics. 1998;212:461–471. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199807)212:3<461::AID-AJA13>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AK, Blumberg B, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Yonei-Tamura S, Tamura K, Tsukui T, de la Pena J, Sabbagh W, Greenwald J, Choe S, Norris DP, Robertson EJ, Evans RM, Rosenfeld MG, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Pitx2 determines left-right asymmetries of internal organs in vertebrates. Nature. 1998;394:545–551. doi: 10.1038/29004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkens; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai LY, Keene DR, Engvall E. Fibrillin, new 350 KDa glycoprotein, is a component of extracellular microfibrils. J.Cell Biology. 1986;103:2499–2509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Treisman R, Garrett N, Mohun T. Muscle-Specific (Carg) And Serum-Responsive (Sre) Promoter Elements Are Functionally Interchangeable In Xenopus Embryos And Mouse Fibroblasts. Development. 1989;106:67–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch AM, Little CD, Markwald RR. Cardiac endothelial heterogeneity defines vascular development as demonstrated by diverse expression of JB3, an antigen of the endocrinal cushion tissue. Developmental Biology. 1994;165:585–601. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]