Abstract

Machado Joseph disease (MJD), also known as Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3), may be the most common dominantly inherited ataxia in the world. Here I will review historical, clinical, neuropathological, genetic and pathogenic features of MJD, and finish with a brief discussion of present, and possible future, treatment for this currently incurable disorder. Like many other dominantly inherited ataxias, MJD/SCA3 shows remarkable clinical heterogeneity, reflecting the underlying genetic defect: an unstable CAG trinucleotide repeat that varies in size among affected persons. This pathogenic repeat in MJD/SCA3 encodes an expanded tract of the amino acid glutamine in the disease protein, which is known as ataxin-3. MJD/SCA3 is one of nine identified polyglutamine neurodegenerative diseases which share features of pathogenesis centered on protein misfolding and accumulation. The specific properties of MJD/SCA3 and its disease protein are discussed in light to what is known about the entire class of polyglutamine diseases.

I. Introduction

First described among individuals of Azorean descent, this hereditary ataxia is now known to exist worldwide. It may, in fact, be the most common dominantly inherited ataxia. The clinical features of this inexorably progressive syndrome can vary greatly among affected persons, even within a family. The basis for this remarkable clinical heterogeneity became clear once the genetic defect was identified to be an unstable CAG trinucleotide repeat. This pathogenic repeat encodes an expanded tract of the amino acid glutamine in the disease protein, now known as ataxin-3. MJD, thus, is one of nine identified polyglutamine neurodegenerative diseases, all of which seem to share features of pathogenesis centered on protein misfolding. For historical reasons, MJD is also known as SCA3: In the 1990s European geneticists identified a presumably distinct ataxia and designated it SCA3, only soon to discover that it was caused by the same expansion as MJD. Although the official Human Genome Organization (HUGO) name for this disorder is MJD, it is also referred to as SCA3 or MJD/SCA3 in the literature. This chapter reviews clinical, neuropathological, genetic and pathogenic features of MJD, and finishes with a brief discussion of treatment for this currently incurable disorder.

II. Clinical and laboratory features

In many countries MJD is the most common dominant ataxia, representing about 20% in most US studies and approaching 50% or more in German, Japanese, Portuguese and Taiwanese series (Table 1) (Schols, 1995; Durr et al., 1996; Moseley et al., 1998; Watanabe et al., 1998; Soong et al., 2001; Silveira et al., 2002; Tsai et al., 2004a). The higher prevalence of MJD in Japan reflects a higher frequency of large normal alleles in the Japanese population, providing a “reservoir” for new expansions (Takano et al., 1998). In most countries, however, the MJD mutation is rarely detected in patients with the diagnosis of “sporadic” ataxia (Schols, 1995; Moseley et al., 1998).

Table 1.

Prevalence of MJD among dominant ataxias

| Study | Ethnicity | %MJD |

|---|---|---|

| Schols et al. (1995) | German | 49 |

| Durr et al. (1996) | European, North African | 28 |

| Inoe et al. (1996) | Japanese | 56 |

| Mosley et al (1998) | US (African American, German) | 21 |

| Takano et al. (1998) | Caucasian | 30 |

| Japanese | 43 | |

| Watanabe et al. (1998) | Japanese | 34 |

| Pujana et al. (1999) | Spanish | 15 |

| Nagaoka et al. (1999) | Japanese | 20 |

| Saleem et al. (2000) | Indian | 5 |

| Soong et al. (2001) | Chinese | 47 |

| Zhou et al. (2001) | Chinese | 35 |

| Silveira et al. (2002) | Portugal/Brazil | 63 |

The core clinical feature in MJD is progressive ataxia due to cerebellar and brainstem dysfunction. Ataxia, however, never occurs in isolation. Numerous other clinical problems reflect progressive dysfunction in the brainstem, oculomotor system, pyramidal and extrapyramidal pathways, lower motor neurons and peripheral nerves (Sequeiros and Coutinho, 1993; Takiyama et al., 1994; Cancel et al., 1995; Sasaki et al., 1995; Durr et al., 1996; Matsumura et al., 1996; Schols et al., 1996; Soong et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 1997; Watanabe et al., 1998; Friedman, 2002; Lin and Soong, 2002; Rub et al., 2002a,b; Rub et al., 2003; Rub et al., 2004a,b; Friedman et al., 2003). Most commonly, affected persons present in the young-adult to mid-adult years with progressive gait imbalance accompanied by vestibular and speech difficulties. Over time a wide range of visual and oculomotor problems may surface, including nystagmus, jerky ocular pursuits, slowing of saccades, disconjugate eye movements, and ophthalmoplegia with lid retraction and apparent bulging eyes. In advanced stages of disease, patients are wheelchair-bound and have severe dysarthria and dysphagia. Patients may also develop facial and temporal atrophy, dystonia, spasticity and amyotrophy. Dementia is not typical, even in advanced disease. There is, however, evidence for subcortical dysfunction and mild cognitive impairment in MJD (Maruff et al., 1996; Zawacki et al., 2002; Kawai et al., 2004). Survival after disease onset ranges from ~20 to 25 years (Klockgether et al., 1998).

The age of disease onset varies widely in MJD; symptom onset has been reported in persons as young as 5 years or as old as 70 years. This variability reflects differences in the size of the repeat: larger repeats cause, on average, earlier disease. For the same reason, the phenotype of MJD can vary markedly (Subramony and Currier, 1996). Researchers have classified MJD into several clinical types based on this variability (Sequeiros and Coutinho, 1993; Matsumura et al., 1996a). “Type I” disease begins earlier (mean age of onset about 25 years) and is characterized by prominent spasticity and rigidity, bradykinesia and minimal ataxia. “Type II” disease, which is the most common form of disease, begins in young to mid adult years and is characterized by progressive ataxia and upper motor neuron signs. “Type III” disease, the late onset form of disease (mean age of onset ~50 years), is characterized by ataxia and significant peripheral nerve involvement resulting in amyotrophy and generalized areflexia. Some researchers have described a “type IV” form of disease characterized by parkinsonism (Cancel et al., 1995; Gwinn-Hardy et al., 2001; Subramony et al., 2002). Although there is no obvious clinical utility to making these distinctions, the fact that different subtypes exist highlights the remarkable heterogeneity of MJD.

More than most other ataxias, MJD can manifest with features suggesting extrapyramidal disease. In some cases bradykinesia, rigidity, dystonia and tremor can closely resemble parkinsonism and may even respond to dopaminergic therapy (Tuite et al., 1995; Buhmann et al., 2003). Severe spasticity and pronounced peripheral neuropathy are also more frequently associated with MJD than most other dominant ataxias. Particularly in late adult onset MJD, peripheral axonal neuropathy can be prominent, and is sometimes accompanied by amyotrophy and fasciculations (Durr et al., 1996; Soong and Lin, 1998). The degree of neuropathy correlates better with the patient's age (i.e. more neuropathy in older patients) than it does with the CAG repeat length. This suggests that age-related impairment of peripheral nerve function is accelerated in MJD.

Sleep problems are common in MJD. Schols and colleagues (Schols et al., 1998) found that MJD patients had greater trouble falling asleep and more nocturnal awakening, with sleep impairment being more common in older patients and in those with prominent brainstem involvement. REM sleep behavior disorder is common, and central sleep apnea has been documented in some patients (Friedman, 2002; Friedman et al., 2003; Iranzo et al., 2003). Daytime sleepiness can also be a major problem. Restless leg syndrome is quite common in MJD, and can be the only manifestation of disease in the rare patient with an intermediate sized repeat expansion (Van Alfen, 2001).

The phenotypic heterogeneity of MJD is mirrored by varying abnormalities noted on brain imaging (Murata et al., 1998; Onodera et al., 1998). The most common MRI finding is pontocerebellar atrophy with a dilated fourth ventricle. MRI abnormalities of the basal ganglia are also detected more often in MJD than in most other SCAs, consistent with the frequent extrapyramidal features (Klockgether et al., 1998). The severity of imaging abnormalities correlates with CAG repeat length: patients with longer repeats, and thus earlier disease, are more likely to show progressive MRI abnormalities at an earlier age. But the severity of MRI findings also correlates with the patient's age independent of the age of onset and repeat length. For instance, elderly patients with late onset MJD can show surprisingly pronounced atrophy on MRI (Onodera et al., 1998). SPECT imaging studies also have documented diffuse CNS abnormalities including reduced dopamine transporter density in the striatum (Etchebehere et al., 2001).

III. Neuropathological features

Signs of neurodegeneration are widespread and variable, most often involving deeper structures of the basal ganglia, various brainstem nuclei and the cerebellum (Sequeiros and Coutinho, 1993; Koeppen et al., 1999; Lin and Soong, 2002; Rub et al., 2002a, b; Rub et al., 2003; Rub et al., 2004a, b). Brain atrophy and neuronal loss have been described in many areas, including the globus pallidus, various thalamic nuclei, subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra, red nucleus, medial longitudinal fasciculus, various pontine nuclei and cranial motor nerve nuclei, superior and middle cerebellar peduncles, cerebellar dentate nucleus, Clarke's column and spinocerebellar tracts, vestibular nucleus, anterior horn cells, posterior columns and posterior root ganglia. The cerebral cortex, olivary nuclei and corticospinal tracts are often spared in MJD. In MJD, even the cerebellar cortex can be relatively spared, which is rather unusual for a SCA.

As in other polyglutamine disease proteins, the disease protein in MJD accumulates within inclusions in various brain regions. These inclusions are often found inside the cell nuclei of specific populations of neurons (Paulson et al., 1997a; Schmidt et al., 1998; Munoz et al., 2002; Uchihara et al., 2002). Neuronal intranuclear inclusions are ubiquitin-positive spheres of one to several microns in diameter that also contain other proteins. NI are particularly abundant in pontine neurons but have also been observed in other brainstem neuronal populations, thalamus, substantia nigra and rarely in the striatum. Extranuclear accumulations also occur in MJD brain (Suenaga et al., 1993). While inclusions are a pathological hallmark of disease, there does not appear to be a clearcut correlation between the regions that have inclusions and the regions that show preferential degeneration.

IV. Genetic Features

Kawaguchi and colleagues (Kawaguchi et al., 1994) discovered the mutation in MJD to be an unstable CAG repeat expansion in the coding region of the MJD1 gene (now termed ATXN3). This 11 exon gene encodes the disease protein ataxin-3, also known as MJDp (Ichikawa et al., 2001; Schmitt et al., 2003). The CAG repeat resides in the 10th exon, where it encodes a polyglutamine tract near the carboxyl terminus of this ~ 42 kilodalton protein.

Since its discovery, the MJD mutation has been identified worldwide as a cause of hereditary ataxia in diverse ethnic groups (Kawaguchi et al., 1994; Maciel et al., 1995; Matilla et al., 1995; Ranum et al., 1995; Schols, 1995; Silveira et al., 1996; Storey et al., 2000; Soong et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2001; Silveira et al., 2002; Tsai et al., 2004a). In many regions of the world, MJD is the most common autosomal dominant ataxia. In the United States, MJD, SCA2 and SCA6 comprise the three most common dominant ataxias.

Unlike repeats in the other CAG/polyglutamine diseases, MJD shows a bit of a gap between normal repeat lengths and fully penetrant expanded repeat lengths. Normal alleles range from 12 to ~43 repeats while expanded alleles are nearly always 60 repeats or greater, ranging up to ~87 in length (Cancel et al., 1995; Maciel et al., 1995; Matilla et al., 1995; Ranum et al., 1995; Sasaki et al., 1995; Durr et al., 1996; Matsumura et al., 1996b). Over 90% of normal alleles have fewer than 31 repeats (Rubinsztein et al., 1995; Takiyama et al., 1995; Gaspar et al., 2001). In the past few years, rare intermediate expansions with repeats of ~51-59 (Takiyama et al., 1995; Van Alfen et al., 2001; Gu et al., 2004), and possibly as low as 45 (Padiath et al., 2005), have been reported to manifest either as a milder form of ataxia or as restless leg syndrome.

Sporadic (i.e. nonfamilial) MJD due to de novo expansions is rare – much less common than in several other polyglutamine diseases including SCA2, SCA6 and Huntington disease (HD). The rather large jump in repeat size that a normal allele would need to undergo to expand into the disease range reduces the likelihood of de novo expansions in MJD.

As in all CAG/polyglutamine diseases, the size of the expansion correlates inversely with age of symptom onset: a correlation coefficient of roughly 0.7 to 0.9 has been observed in many patient series. On average, larger repeats cause earlier disease onset and may be associated with faster disease progression. The size of the expanded repeat length also determines, in part, the clinical phenotypes mentioned above. Patients with type I disease, the early onset dystonic form of disease, typically have larger repeats than those with type II and III phenotypes. In one study, Sasaki and colleagues (Sasaki et al., 1995) found that patients with type I, II and III phenotypes had average repeat sizes of 80, 76, and 73, respectively. The largest CAG repeats are often associated with pyramidal signs and dystonia (Jardim et al., 2001), whereas the smallest repeat size (< 73) is associated with peripheral neuropathy (Durr et al., 1996; Schols et al., 1996). Durr and colleagues (1996) noted that many clinical signs, including amyotrophy, ophthalmoplegia and dysphagia, correlate better with disease duration than with CAG repeat size. Indeed, the peripheral nervous system findings of MJD seem to have a strong, age-dependent component.

Anticipation, the tendency for disease to worsen from generation to generation, occurs in MJD. Durr and colleagues (Durr et al., 1996) and Takiyama and colleagues (Takiyama et al., 1995) each noted a mean anticipation of approximately 10 years for age of onset from one generation to the next. Why does anticipation occur? The tendency for repeat sizes to expand from one generation to the next, coupled with the fact that longer repeats cause earlier onset disease, leads to disease symptoms showing up earlier in successive generations. Over half of parent-child transmissions of the MJD repeat are unstable, with ~ 75% further expanding in the next generation (Maciel et al., 1995; Takiyama et al., 1995). Anticipation seems to be slightly more prominent with paternal than with maternal inheritance, though the paternal bias is not nearly as profound as it is with, say, Huntington disease.

Although MJD is a dominant disorder there may be a gene dosage effect. In a Yemenese family, several individuals homozygous for MJD expansions were found to have earlier onset and more rapid progression than heterozygous individuals (Lerer et al., 1996). The expansions in this family were relatively small (66 to 72) and some heterozygotes remained asymptomatic well into their 7th decade. This limited evidence suggests a dose dependency to the toxicity of the expansion. Consistent with a gene dosage effect, homozygous mice are more severely impaired than heterozygous mice in two recently developed mouse models (Cemal et al., 2002; Goti et al., 2004) and the severity of the phenotype in a Drosophila model of MJD also correlated with the level of transgene expression (Warrick et al., 1998).

A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) exists immediately after the CAG repeat. This SNP is usually guanine in normal alleles, but is cytosine in all expanded alleles. Whether this nucleotide difference contributes to pathogenesis is unknown, but it has been suggested to play a role in repeat instability (Igarashi et al., 1996; Matsumura et al., 1996b). This SNP has been exploited in RNAi studies that selectively suppressed expression of the mutant allele while sparing expression of the normal allele (Miller et al., 2003).

The normal repeat is stably transmitted and shows no somatic mosaicism in repeat size. In contrast, expanded MJD1 repeats display a modest degree of somatic mosaicism, most notably in the cerebellar cortex (Maciel et al., 1997). In the cerebellum this leads to smaller, not larger, expanded repeats, and thus somatic mosaicism cannot explain the preferential involvement of cerebellum in disease.

V. Pathogenesis

Insights from the MJD1 gene product, ataxin-3

Scientists now recognize that protein context plays a major role in polyglutamine disease pathogenesis (La Spada and Taylor, 2003; Williams and Paulson, 2008). Thus, understanding the disease protein in which the MJD expansion occurs is important to understanding the mechanism of neurodegeneration. The MJD1 gene encodes ataxin-3 (figure 1), also known as ATXN3, a 42 kilodalton protein that is widely expressed in the CNS and elsewhere (Nihiyama et al., 1996; Paulson et al., 1997a; Wang et al., 1997; Schmidt et al., 1998; Tait et al., 1998; Schmitt et al., 2003; Do Carmo Costa et al., 2004). This discrepancy between widespread expression of ataxin-3 and selective neuronal degeneration is reminiscent of the many neurodegenerative diseases in which selective tissue vulnerability cannot be explained by restricted disease protein expression. Ataxin-3 exists in at least two major splice forms that differ only in their carboxyl-termini. Both contain the polyglutamine domain encoded by exon 10 and both appear to be expressed in disease brain (Schmidt et al., 1998).

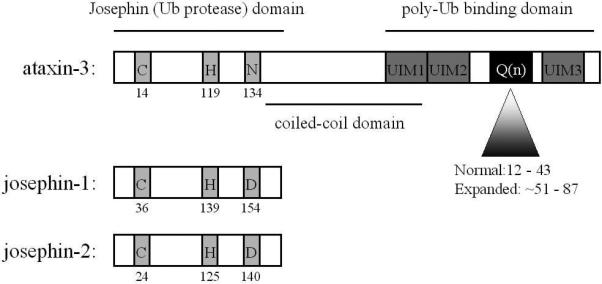

Figure 1. Ataxin-3 and related Josephin domain proteins.

Ataxin-3 is a relatively small protein with a glutamine repeat near the carboxyl terminus. The approximate ranges for normal and disease repeats are shown. The N-terminal conserved “josephin” catalytic domain, a predicted coiled-coil domain and several ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs) are also shown. Ataxin-3 is one member of the small Josephin DUB family, two other members of which are josephin-1 and josephin-2, encoded by different genes. All three proteins share the catalytic amino acid triad (C, H, and D/N) and function as DUBs.

Ataxin-3 is a small, soluble protein that can shuttle in and out of the nucleus (Chai et al., 2002). In many cells a fraction of the cellular pool of ataxin-3 is intranuclear, bound to the nuclear matrix (Tait et al., 1998; Trottier et al., 1998; Perez et al., 1999). In unaffected brain and in normal neurons, ataxin-3 appears to be largely cytoplasmic. In disease brain, however, the protein tends to concentrate in neuronal cell nuclei (Nihiyama et al., 1996; Paulson et al., 1997a, b; Schmidt et al., 1998; Goti et al., 2004). Why ataxin-3 preferentially localizes to neuronal cell nuclei in disease is unknown, but this same phenomenon has been described in other polyglutamine diseases including Huntington Disease. Interestingly, in cell models nuclear ataxin-3 is more easily recognized by a polyglutamine-specific antibody than is cytoplasmic ataxin-3, suggesting that the conformation of the protein differs depending on its subcellular location (Perez et al., 1999).

The rather large and polymorphic polyglutamine tract present in normal human ataxin-3 is unique to human ataxin-3. Because ataxin-3 orthologs in other vertebrates have a much smaller polyglutamine domain, a large glutamine repeat is clearly not essential for the core functions of ataxin-3. Ataxin-3 orthologs in other species do, however, share an evolutionarily conserved, N-terminal “josephin” domain (Scheel et al., 2003). Two other human genes encode josephin-containing proteins, aptly named josephin-1 and josephin-2 (Swiss-Prot accession numbers Q15040 and Q8TAC2, respectively). These two proteins are approximately 25% identical to the josephin domain of ataxin-3, but they lack the other protein motifs of ataxin-3. In addition to its josephin and polyglutamine domains, ataxin-3 has a predicted coiled-coil domain, two closely spaced ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs) upstream of the polyglutamine domain and, in one of two major splice variants, a third UIM downstream of the polyglutamine tract.

What is the function of ataxin-3? It appears to be a unique de-ubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) that preferentially binds and cleaves longer chains of ubiquitin. The josephin domain encodes the enzymatic guts of the enzyme. The josephin domain has a rather rigid globular structure with a papain-like fold to the protease pocket; in contrast, the polyglutamine-containing latter half of the protein has a more flexible structure (Masino et al., 2003; Chow et al., 2004; Masino et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2005; Nicastro et al., 2005). Ataxin-3 can cleave poly-ubiquitin chains from test substrates and poly-ubiquitin chains in vitro and, when the active site cysteine residue is mutated, this de-ubiquitinating activity is lost (Burnett et al., 2003; Berke et al., 2005; Bowman et al., 2005; Mao et al., 2005; Nicastro et al., 2005; Winborn et al., 2008). When expressed in cells, catalytically inactive ataxin-3 causes a buildup of poly-ubiquitinated proteins (Berke et al., 2005).

The precise physiological roles of this unusual DUB remain unclear. A clue comes from the fact that ataxin-3 has multiple UIMs neighboring the polyglutamine domain. UIMs are protein motifs that mediate ubiquitin binding to proteins implicated in traditional (i.e. proteasomal) and nontraditional roles of ubiquitin pathways (Hofmann and Falquet, 2001). If the UIMs of ataxin-3 are mutated, ubiquitin binding is lost. Ataxin-3 preferentially recognizes chains of three or greater ubiquitin molecules with a fairly high affinity (Chai et al., 2004). When the proteasome is pharmacologically inhibited, the broad range of poly-ubiquitinated proteins that accumulate in cells bind to, and coprecipitate with, ataxin-3 (Donaldson et al., 2003; Chai et al., 2004; Bowman et al., 2005).

An attractive model for ataxin-3 function is that its UIMs regulate or restrict the types of ubiquitinated species, or types of ubiquitin chain linkages, upon which it can act (Winborn et al 2008). Most DUBs do not have UIMs. Because ataxin-3 has UIMs that preferably bind longer poly-ubiquitin chains, ataxin-3 likely “prefers” to act on heavily ubiquitinated substrates. Recent studies have confirmed this enzymatic preference for longer chains while also revealing a preference for particular types of ubiquitin chain linkages (Winborn et al 2008). Among its possible functions, ataxin-3 could serve to edit ubiquitin chain production by ubiquitin ligases and trim heavily ubiquitinated species before their presentation to the proteasome. Substrate delivery to the proteasome typically requires that the substrate be conjugated to an ubiquitin chain at least four ubiquitin molecules. Excessively long or branched chains, however, might impede this delivery. It is appealing to speculate that ataxin-3 trims branched or excessively long ubiquitin chains on substrates destined for proteasomal degradation. Through this editing action, which could even occur while chains are being generated, ataxin-3 would increase the efficiency of substrate delivery to the proteolytic chamber of the proteasome. There is no proof for this model as yet, however.

Mounting evidence suggests that ataxin-3 functions, at least in part, in the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway. Ataxin-3 cosediments with proteasomes in yeast and interacts with at least two other ubiquitin binding proteins already implicated in substrate delivery to the proteasome, VCP/p97 and HHR23 (Doss-Pepe et al., 2003). Presentation of substrates to the 26S proteasome is a complex process mediated by a range of cellular factors, one of which may be ataxin-3. Regardless of whether ataxin-3 directly acts in proteasomal function, its ubiquitin-associated activities link ataxin-3 to protein quality control pathways already implicated in polyglutamine disease pathogenesis.

Protein misfolding as a central feature of pathogenesis

A common link among polyglutamine diseases is the presence of neuronal inclusions containing the mutant protein (Taylor et al., 2002; Ross and Poirier, 2004; Berke et al., 2005). Their discovery in MJD and other polyglutamine diseases suggested that protein misfolding is central to pathogenesis (Williams and Paulson, 2008). Consistent with this view, recombinant mutant polyglutamine proteins adopt amyloid-like conformations and form aggregates in vitro (Scherzinger et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2002; Kayed et al., 2003). Importantly, the repeat threshold for aggregation mirrors the threshold length for human disease. Furthermore, recombinant mutant ataxin-3 adopts increased amyloid-like structure and forms aggregates in vitro, supporting an altered conformation for the disease protein (Bevivino and Loll, 2001). These and other lines of evidence suggest that conformational abnormalities of mutant ataxin-3 underlie its pathogenic nature.

Yet while inclusions are found in various polyglutamine disease brains, their distribution correlates rather poorly with regions of degeneration. This is also the case in MJD, where degeneration in many deep basal ganglionic, thalamic, brainstem and spinal cord regions is not always accompanied by significant inclusions.

To address whether aggregates are directly toxic, Wetzel and colleagues delivered preformed, fibrillar aggregates to cultured cells (Yang et al., 2002). Aggregates generated from expanded or normal repeats were toxic to cells, provided that they were transported into the nucleus. In contrast, monomeric forms of normal and expanded polyglutamine had no effect. While this result suggests that aggregates are directly toxic, pure polyglutamine complexes of this sort likely differ from the inclusions found in neurons. Finkbeiner and colleagues (Arrasate et al., 2004) studied the toxicity of cell-derived inclusions (as opposed to preformed aggregates) by following transfected neurons over time to determine the causal relationship of inclusion formation to cell death. Neurons containing visible inclusions were less likely to die than neurons in which the mutant protein remained diffuse, suggesting that inclusions play a neuroprotective role.

These seemingly contradictory findings are compatible when one recognizes that the biochemical process of aggregation and the formation of inclusions are not necessarily one and the same. Surely we have not heard the end of speculation about inclusions and aggregates. But it seems safe to conclude that, at a minimum, inclusions represent biological markers of a failure in aberrant protein clearance and may, in fact, represent a successful cellular response to the problem of protein aggregation.

The evidence for protein misfolding and aggregation in MJD and other polyglutamine diseases has focused attention on the importance of cellular protein quality control machinery (Williams and Paulson, 2008). Cells must ensure that newly made proteins fold correctly and that proteins damaged by physiological stress or by mutations are dealt with efficiently. Two critical components to quality control are chaperone mediated protein folding and ubiquitin-proteasome mediated protein degradation. If a protein fails to achieve a native conformation, heat-shock protein chaperones assist in refolding or disaggregating. For many misfolded cytosolic or nuclear proteins, the principal route for protein destruction is the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. If the concentration of misfolded proteins exceeds cellular folding and degradative capacity, these proteins can form insoluble, intracellular aggregates or inclusions.

Growing evidence implicates chaperones in modulating polyglutamine disease protein misfolding and toxicity. In transgenic flies, for example, overexpression of specific Hsp chaperones markedly suppresses polyglutamine toxicity (Warrick et al., 1999). Genetic screens in C. elegans yeast and flies further point to a role for chaperones in buffering the toxicity of polyglutamine proteins, although genes in other pathways have also been implicated (Willingham et al., 2003; Muchowski and Wacker, 2005).

The data are less compelling for involvement of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. Ubiquitin and proteasomal components do localize to NI's in MJD disease brain and various model systems (Paulson et al., 1997b; Chai et al., 1999; Schmidt et al., 2002), and inhibiting the proteasome does increase polyglutamine aggregation in cell-based models (Chai et al., 1999). Moreover, polyglutamine aggregates inhibit proteasome activity in overexpressing cells (Bence et al., 2001), and expanded polyglutamine repeats are poorly digested by proteasomes in a test tube (Venkatraman et al., 2004). Taken together, these results suggest a vicious cycle in which mutant polyglutamine proteins compromise the very cellular defenses normally marshaled against them. Despite these data, however, there is no compelling in vivo evidence that mutant polyglutamine proteins expressed at physiological levels inhibit the proteasome in disease tissues [e.g. 6]. Moreover, in one study using transfected cells, mutant ataxin-3 proved to be as easily degraded as expanded ataxin-3 (Berke et al., 2005).

Certain ubiquitin ligases link the chaperone system to the ubiquitin dependent arms of protein quality control. For example, CHIP (Carboxy-terminus of Hsc70 Interacting Protein) appears to be a key player in the nervous system's handling of mutant polyglutamine proteins, including ataxian-3. In a mouse model of MJD, reduction or elimination of CHIP markedly accelerates the disease phenotype which directly correlates with the accumulation of biochemically detectable microaggregates of mutant ataxin-3 (Williams et al., 2008).

Rather than a wholesale clogging of the proteasomal or chaperone arms of quality control, perhaps more subtle impairment is one of several insults that the neuron faces when chronically exposed to expanded polyglutamine. But given the intriguing connection of the DUB ataxin-3 to ubiquitin-dependent pathways, the theory that proteasomal action is affected in MJD should be looked at with a fresh perspective.

Mechanistic Insights from Animal Models

Ikeda et al (Ikeda et al., 1996) created the first animal model of MJD by expressing ataxin-3 in mice with a Purkinje cell-specific promoter. Mice expressing full-length, mutant ataxin-3 were normal, but mice expressing a truncated, expanded polyglutamine fragment developed progressive ataxia with Purkinje cell loss. This was the first compelling in vivo evidence that protein context critically influences the toxicity of expanded polyglutamine, a point since corroborated by many studies in other polyglutamine diseases (La Spada and Taylor, 2003). Unfortunately, this mouse model no longer exists.

Results in a Drosophila model expressing full-length ataxin-3 (Warrick et al., 2005) shed light on how the protein context of ataxin-3 influences pathogenesis. Bonini and colleagues initially used a truncated ataxin-3 fragment to model polyglutamine neurodegeneration in the fruit fly (Warrick et al., 1998). This ataxin-3 fragment proved to be highly toxic. In contrast, full-length expanded ataxin-3 with an even longer repeat caused a much milder, selectively neurotoxic phenotype, and normal ataxin-3 actually suppressed the toxicity of other polyglutamine disease proteins (Warrick et al., 2005). This suppression by ataxin-3 required its ubiquitin-linked functions, suggesting that ataxin-3 normally participates in ubiquitin-dependent protein quality control. Perhaps mutant ataxin-3 counteracts its own toxicity through its ubiquitin-related functions as a DUB.

The study of MJD has been aided by the recent development of transgenic mouse models (Cemal et al., 2002; Goti et al., 2004, Bichelmeier et al., 2007; Boy et al., 2009, 2010). All four models express full-length ataxin-3. Cemal and colleagues (Cemal et al., 2002) generated mice expressing normal or expanded alleles of the human ATXN3 (MJD) gene contained within a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC). These mice express ataxin-3 widely in the brain and body, presumably in the normal distribution of the ATXN3 gene. Mice expressing expanded ataxin-3 develop a mild cerebellar phenotype with neuronal cell loss, gliosis and abundant inclusion formation. Because this model expresses the full ATXN3 gene in its normal genomic context, it is well suited for many important studies: 1) the molecular basis of regional neuronal selectivity; 2) the mechanism underlying repeat instability; and 3) the potential contribution to pathogenesis of a CAG repeat-induced, translational frame shift in the MJD1 protein (Toulouse et al., 2005).

Colomer and colleagues created a second MJD transgenic mouse model that expresses full-length ataxin-3 cDNA (Goti et al., 2004). Mice expressing mutant ataxin-3 above a critical concentration develop a progressive motor phenotype with ataxia, weight loss and early death. The dose dependency in this mouse is striking: whereas hemizygous mice have little or no phenotype, homozygous mice develop severe, early onset disease. This model should help define the role of neuronal dysfunction in MJD, because it displays a severe behavioral phenotype despite apparently minimal brain atrophy. This model, however, is based on a cDNA transgene that is not the common, full length splice isoform expressed in brain.

Bichelmeier and colleagues created several transgenic mouse lines, some expressing ataxin-3 with expansions of 70 and others with 148 gletamine residues. One particularly interesting result the authors noted is that, when ataxin-3 is forced into the nucleus (by addition of a nuclear localization signal), the toxicity and phenotype are more severe. This is consistent with the view that an important aspect of ataxin-3 toxicity occurs within the nucleus.

The most recently published MJD mouse model inducibly expresses ataxin-3 (Boy et al., 2009). Importantly, when mutant ataxin-3 expression is turned off in this model, early disease symptoms are mitigated. This result suggests that efforts to reduce expression of the mutant protein may have therapeutic potential.

The existence now of complementary transgenic mouse models of MJD should enhance investigations into potential pathogenic mechanisms. Four postulated mechanisms in MJD and other polyglutamine diseases are 1) the production of a toxic proteolytic fragment, 2) transcriptional dysregulation, 3) perturbation of axonal transport, and 4) mitochondrial impairment.

For example, a putative, C-terminal ataxin-3 fragment was reported to accumulate in the brain of transgenic MJD mice (Goti et al., 2004). The protease responsible for this presumed cleavage in unknown, but Berke and colleagues (Berke et al., 2004) independently reported that a similar sized ataxin-3 fragment was generated by caspases in cells undergoing apoptosis. As shown in MJD models in cells, mice and flies (Ikeda et al., 1996; Paulson et al., 1997b; Warrick et al., 1998; Jana and Nukina, 2004), truncation of ataxin-3 can accelerate aggregation and toxicity although full-length ataxin-3 can form inclusions in the absence of any detectable cleavage (e.g., Evert et al., 1999). Proving that such a proteolytic event is central to pathogenesis will be difficult, but worth pursuing if compounds can be found to block proteolysis.

The results of several studies are consistent with the hypothesis that expanded polyglutamine proteins trigger disease by perturbing gene transcription through aberrant protein-protein interactions (Sugars and Rubinsztein, 2003). In MJD brain the basal transcription factor TATA binding protein (which is also the SCA17 disease protein) localizes to nuclear inclusions (Perez et al., 1998). Ataxin-3 also can repress CREB binding protein (CBP)-dependent transcription in transfected cells (Chai et al., 2001) and recruit CBP into inclusions (Chai et al., 2002). Evert and colleagues have shown that mutant ataxin-3 upregulates cytokine genes in a neural cell line and that normal and mutant ataxin-3 have divergent effects on transcriptional profiles in cells (Evert et al., 2003). One now hopes that similar gene expression analyses and directed studies of specific transcription-associated factors will be performed in mouse models of MJD.

The occurrence of motor neuron loss and peripheral neuropathy in some MJD patients suggests that axonal dysfunction plays a significant role in disease. Histopathological analyses of certain polyglutamine disease brains show widespread neuritic inclusions, suggesting that perturbation of axonal transport contributes to pathogenesis (Gunawardena and Goldstein, 2005). Aggregated disease protein may physically block transport; expression of a mutant ataxin-3 fragment in Drosophila, for example, was found to cause axonal blockages (Gunawardena et al., 2003). In addition, ataxin-3 interacts with dynein and the cytosolic histone deacetylase 6 during transport of misfolded proteins in cultured cells, thus linking ataxin-3 to cytoskeletal transport processes (Burnett and Pittman, 2005). The potential role of axonal perturbation in MJD clearly warrants further study.

Finally, impairment of mitochondria could trigger neuronal dysfunction and death in MJD and other polyglutamine diseases. While most evidence implicating mitochondrial involvement in polyglutamine toxicity is from other diseases, a few studies suggest mutant ataxin-3 has effects on mitochondria. For example, Tsai et al (Tsai et al., 2004b) reported decreased Bcl-2 and increased cytochrome C levels in cells expressing mutant ataxin-3. One way expanded polyglutamine proteins could disrupt normal mitochondrial function is through the formation of aberrant ion channels (Monoi et al., 2000). For this to happen, however, the polyglutamine domain would likely need to become separated from most of it surrounding polypeptide through a proteolytic event. While ataxin-3 may undergo proteolysis in transgenic mice (Goti et al., 2004), there is no evidence that ataxin-3 fragments can form such channels. The availability of transgenic mouse models will now allow scientists to determine whether mutant ataxin-3 directly binds mitochondria or alters mitochondrial activity in vivo.

VIII. Toward therapy

MJD is a relentlessly progressive disease for which there is currently no cure. It is important to remember, however, that numerous symptoms occurring in MJD can respond to symptomatic therapy. For example, some patients have parkinsonian signs that may improve with dopaminergic agents (Tuite et al., 1995; Buhmann et al., 2003). The restless leg syndrome experienced by many MJD patients can also respond to dopaminergic agents. Aberrant sleep patterns and daytime sleepiness, a common complaint in MJD, can benefit from sympathomimetic agents such as amphetamines and modafanil. Some patients may find their level of alertness benefited by amantadine, though the pharmacologic basis of this response is unknown. Unfortunately, none of these medications has been studied in a double-bind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. This is due, in part, to the difficulty of performing multi-center trials for a disease as rare and as clinically heterogeneous as MJD.

A major goal of current research in MJD is to understand disease mechanisms in order that the disease might be slowed or prevented altogether. Currently there is no proven, preventive medicine for MJD or any polyglutamine disease. Hopefully, some elements of pathogenesis are shared across this class of diseases. If so, ongoing studies in HD may identify useful compounds to slow disease. Clinicians caring for patients with MJD should keep a close eye on HD preventive trials testing compounds that, for example, enhance bioenergetics (e.g. coenzyme Q, creatine), inhibit mitochondrial mediated apoptotic signaling (e.g. minocycline) or inhibit histone deacetyltransferases (e.g. phenylbutyrate). In a small scale HD trial (Hersch et al., 2006), creatine significantly reduced levels of a potential disease biomarker, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, a byproduct of oxidative DNA damage. While this study was only a safety and tolerability study, it suggests that if this biomarker is a reliable indicator of toxic effects, then creatine may benefit those with HD and possibly those with MJD.

One potentially powerful route to therapy is to turn off the disease gene. Because the mutant MJD1 allele acts through a dominant toxic mechanism, suppressing its expression should be beneficial regardless of the precise cellular route(s) by which ataxin-3 is toxic to neurons. RNA interference has been used successfully to silence ataxin-3 in cell and animal models (Miller et al., 2003) and other polyglutamine disease genes in mouse models (Xia et al., 2004; Harper et al., 2005). With the recent development of MJD transgenic mice that recapitulate important disease features, RNAi therapy for MJD now can be tested more thoroughly in vivo. Due to the fairly widespread brain involvement in MJD, however, efficient delivery to a wide range of target neurons may be necessary to slow or stop disease.

Acknowledgements

Research on SCA3/MJD and ataxin-3 in the author's lab is funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant NS038712), the National Ataxia Foundation and the Fauver Family Ataxia Research Fund.

References

- Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntington and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bence NF, Sampat RM, Kopito RR. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science. 2001;292:1552–5. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5521.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke SJ, Chai Y, Marrs GL, Wen H, Paulson HL. Defining the role of ubiquitin-interacting motifs in the polyglutamine disease protein, ataxin-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(36):32026–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506084200. Epub 2005 Jul 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke SJ, Schmied FA, Brunt ER, Ellerby LM, Paulson HL. Caspase-mediated proteolysis of the polyglutamine disease protein ataxin-3. J. Neurochem. 2004 May;89(4):908–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevivino AE, Loll PJ. An expanded glutamine repeat destabilizes native ataxin-3 structure and mediates formation of parallel beta -fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11955–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211305198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichelmeier U, Schmidt T, Hübener J, Boy J, Rüttiger L, Häbig K, Poths S, Bonin M, Knipper M, Schmidt WJ, Wilbertz J, Wolburg H, Laccone F, Riess O. Nuclear localization of ataxin-3 is required for the manifestation of symptoms in SCA3: in vivo evidence. J Neurosci. 2007 Jul 11;27(28):7418–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman AB, Yoo SY, Dantuma NP, Zoghbi HY. Neuronal dysfunction in a polyglutamine disease model occurs in the absence of ubiquitin-proteasome system impairment and inversely correlates with the degree of nuclear inclusion formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:679–691. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boy J, Schmidt T, Schumann U, Grasshoff U, Unser S, Holzmann C, Schmitt I, Karl T, Laccone F, Wolburg H, Ibrahim S, Riess O. A transgenic mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 resembling late disease onset and gender-specific instability of CAG repeats. Neurobiol Dis. 2009 Aug 20; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boy J, Schmidt T, Wolburg H, Mack A, Nuber S, Böttcher M, Schmitt I, Holzmann C, Zimmermann F, Servadio A, Riess O. Reversibility of symptoms in a conditional mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 Nov 15;18(22):4282–95. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhmann C, Bussopulos A, Oechsner M. Dopaminergic response in Parkinsonian phenotype of Machado-Joseph disease. Mov Disord. 2003 Feb;18(2):219–21. doi: 10.1002/mds.10322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett B, Li F, Pittman RN. The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin-3 binds polyubiquitylated proteins and has ubiquitin protease activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2003 Dec 1;12(23):3195–205. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg344. Epub 2003 Oct 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett BG, Pittman RN. The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin 3 regulates aggresome formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Mar 22;102(12):4330–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407252102. Epub 2005 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancel G, Abbas N, Stevanin G, Durr A, Chneiweiss H, Neri C, Duyckaerts C, Penet C, Cann HM, Agid Y, Brice A. Marked phenotypic heterogeneity associated with expansion of a CAG repeat sequence at the spinocerebellar ataxia 3/Machado-Joseph disease locus. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:809–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cemal CK, Carroll CJ, Lawrence L, Lowrie MB, Ruddle P, Al-Mahdawi S, King RH, Pook MA, Huxley C, Chamberlain S. YAC transgenic mice carrying pathological alleles of the MJD1 locus exhibit a mild and slowly progressive cerebellar deficit. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(9):1075–94. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Berke SS, Cohen RE, Paulson HL. Poly-ubiquitin binding by the polyglutamine disease protein ataxin-3 links its normal function to protein surveillance pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jan 30;279(5):3605–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310939200. Epub 2003 Nov 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Koppenhafer SL, Shoesmith S, Perez MK, Paulson HL. Evidence of proteasome involvement in polyglutamine disease: localization to nuclear inclusions in SCA3/MJD and suppression of polyglutamine aggregation in vitro. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:673–682. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Shao J, Miller VM, Williams A, Paulson HL. Live-cell imaging reveals divergent intracellular dynamics of polyglutamine disease proteins and supports a sequestration model of pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(14):9310–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152101299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Wu L, Griffin JD, Paulson HL. The role of protein composition in specifying nuclear inclusion formation in polyglutamine disease. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):44889–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Ferrone FA, Wetzel R. Huntington's disease age-of-onset linked to polyglutamine aggregation nucleation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11884–11889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182276099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow MK, Mackay JP, Whisstock JC, Scanlon MJ, Bottomley SP. Structural and functional analysis of the Josephin domain of the polyglutamine protein ataxin-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004 Sep 17;322(2):387–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Carmo Costa M, Gomes-da-Silva J, Miranda CJ, Sequeiros J, Santos MM, Maciel P. Genomic structure, promoter activity, and developmental expression of the mouse homologue of the Machado-Joseph disease (MJD) gene. Genomics. 2004 Aug;84(2):361–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson KM, Li W, Ching KA, Batalov S, Tsai CC, Joazeiro CA. Ubiquitin-mediated sequestration of normal cellular proteins into polyglutamine aggregates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Jul 22;100(15):8892–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530212100. Epub Jul 11 (2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss-Pepe EW, Stenroos ES, Johnson WG, Madura K. Ataxin-3 interactions with rad23 and valosin-containing protein and its associations with ubiquitin chains and the proteasome are consistent with a role in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003 Sep;23(18):6469–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6469-6483.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durr A, Stevanin G, Cancel G, Duyckaerts C, Abbas N, Didierjean O, Chneiweiss H, Benomar A, Lyon-Caen O, Julien J, Serdaru M, Penet C, Agid Y, Brice A. Spinocerebellar ataxia 3 and Machado-Joseph disease: clinical, molecular and neuropathological features. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:490–499. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchebehere E, Cendes F, Lopes-Cendes I, Pereira JA, Lima MC, Sansana CR, Silva CA, Camargo MF, Santos AO, Ramos CD, Camargo EE. Brain Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Machado-Joseph Disease. Arch Neurology. 2001;58:1257–1263. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.8.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evert BO, Vogt IR, Vieira-Saecker AM, Ozimek L, de Vos RA, Brunt ER, Klockgether T, Wullner U. Gene expression profiling in ataxin-3 expressing cell lines reveals distinct effects of normal and mutant ataxin-3. J Neuropathol Exp Neuro. 2003 Oct;62(10):1006–18. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.10.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evert BO, Wullne U, Schulz JB, Weller M, Groscurth P, Trottier Y, Brice A, Klockgether T. High level expression of expanded full-length ataxin-3 in vitro causes cell death and formation of intranuclear inclusions in neuronal cells. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1169–1176. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JH. Presumed rapid eye movement behavior disorder in Machado-Joseph disease (spinocerebellar ataxia type 3). Mov Disord. 2002 Nov;17(6):1350–3. doi: 10.1002/mds.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JH, Fernandez HH, Sudarsky LR. REM behavior disorder and excessive daytime somnolence in Machado-Joseph disease (SCA-3). Mov Disord. 2003 Dec;18(12):1520–2. doi: 10.1002/mds.10590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar C, Lopes-Cendes I, Hayes S, Goto J, Arvidsson K, Dias A, Silveira I, Maciel P, Coutinho P, Lima M, Zhou YX, Soong BW, Watanabe M, Giunti P, Stevanin G, Riess O, Sasaki H, Hsieh M, Nicholson GA, Brunt E, Higgins JJ, Lauritzen M, Tranebjaerg L, Volpini V, Wood N, Ranum L, Tsuji S, Brice A, Sequeiros J, Rouleau GA. Ancestral Origins of the Machado-Joseph Disease Mutation: A Worldwide Haplotype Study. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:523–528. doi: 10.1086/318184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goti D, Katzen SM, Mez J, Kurtis N, Kiluk J, Ben-Haiem L, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Kakizuka A, Sharp AH, Ross CA, Mouton PR, Colomer V. A mutant ataxin-3 putative-cleavage fragment in brains of Machado-Joseph disease patients and transgenic mice is cytotoxic above a critical concentration. J Neurosci. 2004 Nov 10;24(45):10266–79. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2734-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Ma H, Wang K, Jin M, Zhou Y, Liu X, Wang G, Shen Y. The shortest expanded allele of the MJD1 gene in a Chinese MJD kindred with autonomic dysfunction. Eur Neurol. 2004;52(2):107–11. doi: 10.1159/000080221. Epub 2004 Aug 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena S, Goldstein LS. Polyglutamine diseases and transport problems: deadly traffic jams on neuronal highways. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:46–51. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena S, Her LS, Brusch RG, Laymon RA, Niesman IR, Gordesky-Gold B, Sintasath L, Bonini NM, Goldstein LS. Disruption of axonal transport by loss of huntingtin or expression of pathogenic polyglutamine proteins in Drosophila. Neuron. 2003;40:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn-Hardy K, Singleton A, O'Suilleabhain P, Boss M, Nicholl D, Adam A, Hussey J, Critchley P, Hardy J, Farrer M. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 Phenotypically Resembling Parkinson Disease in a Black Family. Arch Neurology. 2001;58:296–299. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper SQ, Staber PD, He X, Eliason SL, Martins IH, Mao Q, Yang L, Kotin RM, Paulson HL, Davidson BL. RNA interference improves motor and neuropathological abnormalities in a Huntington's disease mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sc. U S A. 2005 Apr 19;102(16):5820–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501507102. Epub 2005 Apr 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch S, Gevorkian S, Marder K, Moskowitz C, Feigin A, Cox M, Como P, Zimmerman C, Lin M, Zhang L, Ulug A, Beal M, Matson W, Bogdanov M, Ebbel E, Zaleta A, Kaneko Y, Jenkins B, Hevelone N, Zhang H, Yu H, Schoenfeld D, Ferrante R, Rosas H. Creatine in Huntington disease is safe, tolerable, bioavailable in brain and reduces serum 8OH2'dG. Neurology. 2006;66:250–2. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194318.74946.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K, Falquet L. Aubiquitin-interacting motif conserved in components of the proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation systems. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;6:347–50. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa Y, Goto J, Hattori M, Toyoda A, Ishii K, Jeong SY, Hashida H, Masuda N, Ogata K, Kasai F, Hirai M, Maciel P, Rouleau GA, Sakaki Y, Kanazawa I. The genomic structure and expression of MJD, the Machado-Joseph disease gene. J Hum Genet. 2001;46:413–22. doi: 10.1007/s100380170060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi S, Takiyama Y, Cancel G, Rogaeva EA, Sasaki H, Wakisaka A, Zhou X-Y, Takano H, Endo K, Sanpei K, Oyake M, Tanaka H, Stevanin G, Abbas N, Durr A, Rogaev EI, Sherrington R, Tsuda T, Ideda M, Cassa E, Nishizawa M, Benomar A, Julien J, Weissenbach J, Want GX, Agid Y, St. George-Hyslop PhH, Brice A, Tsuji S. Intergenerational instability of the CAG repeat of the gene for Machado-Joseph disease (MJD1) is affected by the genotype of the normal chromosome: implications for the molecular mechanisms of the instability of the CAG repeat. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:923–932. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.7.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Yamaguchi M, Sugai S, Aze Y, Narumiya S, Kakizuka A. Expanded polyglutamine in the Machado-Joseph disease protein induces cell death in vitro and in vivo. Nat Genet. 1996;13:196–202. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iranzo A, Munoz E, Santamaria J, Vilaseca I, Mila M, Tolosa E. REM sleep behavior disorder and vocal cord paralysis in Machado-Joseph disease. Mov Disord. 2003 Oct;18(10):1179–83. doi: 10.1002/mds.10509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana NR, Nukina N. Misfolding promotes the ubiquitination of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3, the defective gene product in SCA3/MJD. Neurotox Res. 2004;6(7-8):523–33. doi: 10.1007/BF03033448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardim L, Pereira M, Silveira I, Ferro A, Sequeiros J, Giugliani R. Neurologic Findings in Machado-Joseph Disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:899–904. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Okamoto T, Taniwaki M, Aizawa M, Inoue M, Katayama S, Kawakami H, Nakamura S, Nishimura M, Akiguchi I. CAG expansions in a novel gene for Machado-Joseph disease at chromosome 14q32.1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:221–228. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y, Takeda A, Abe Y, Washimi Y, Tanaka F, Sobue G. Cognitive impairments in Machado-Joseph disease. Arch Neurol. 2004 Nov;61(11):1757–60. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.11.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether T, Ludtke R, Kramer B, Abela M, Burk K, Schols L, Riess O, Laccone F, Boesch S, Lopes-Cendes I, Brice A, Inzelberg R, Zilber N, Dichgans J. The natural history of degenerative ataxia: a retrospective study in 466 patients. Brain. 1998;121:589–600. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether T, Skalej M, Wedekind D, Luft AR, Welte D, Schulz JB, Abele M, Burk K, Laccone F, Brice A, Dichgans J. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia type I. MRI based volumetry of posterior fossa structures and basal ganglia in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, 2 and 3. Brain. 1998;121:1687–1693. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.9.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppen AH, Dickson AC, Lamarche JB, Robitaille Y. Synapses on the hereditary ataxias. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1999;58:748–764. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Spada AR, Taylor JP. Polyglutamines placed into context. Neuron. 2003 Jun 5;38(5):681–4. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerer I, Merims D, Abeliovich D, Zlotogora J, Gadoth N. Machado-Joseph disease: Correlation between clinical features, the CAG repeat length and homozygosity for the mutation. Eur J Hum Genet. 1996;4:3–7. doi: 10.1159/000472162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KP, Soong BW. Peripheral neuropathy of Machado-Joseph disease in Taiwan: a morphometric and genetic study. Eur. Neurol. 2002;48(4):210–7. doi: 10.1159/000066169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel P, Gaspar C, DeStefano AL, Silveira I, Coutinho P, Radvany J, Dawson DM, Sudarsky L, Guimaraes J, Loureiro JEL, Nezarati MM, Corwin LI, Lopes-Cendes I, Rooke K, Rosenberg R, MacLeod P, Farrer LA, Sequeiros J, Rouleau GA. Correlation between CAG repeat length and clinical features in Machado-Joseph disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:54–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel P, Lopes-Cendes I, Kish S, Sequeiros J, Rouleau GA. Mosaicism of the CAG repeat in CNS tissue in relation to age at death in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 and Machado-Joseph disease patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:993–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Senic-Matuglia F, Di Fiore PP, Polo S, Hodsdon ME, De Camilli P. Deubiquitinating function of ataxin-3: Insights from the solution structure of the Josephin domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Sep 6;102(36):12700–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506344102. Epub 2005 Aug 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruff P, Tyler P, Burt T, Currie B, Burns C, Currie J. Cognitive deficits in Machado- Joseph disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:421–427. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama H, Izumi Y, Morino H, Oda M, Toji H, Nakamura S, Kawakami H. Difference in disease-free survival curve and regional distribution according to subtype of spinocerebellar ataxia: a study of 1,286 Japanese patients. Am J Med Genet. 2002 Jul 8;114(5):578–83. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masino L, Musi V, Menon RP, Fusi P, Kelly G, Frenkiel TA, Trottier Y, Pastore A. Domain architecture of the polyglutamine protein ataxin-3: a globular domain followed by a flexible tail. FEBS Lett. 2003 Aug 14;549(1-3):21–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00748-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masino L, Nicastro G, Menon RP, Dal Piaz F, Calder L, Pastore A. Characterization of the structure and the amyloidogenic properties of the Josephin domain of the polyglutamine-containing protein ataxin-3. J Mol Biol. 2004 Dec 3;344(4):1021–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilla T, McCall A, Subramony SH, Zoghbi HY. Molecular clinical correlations in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 and Machado-Joseph disease. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:68–72. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura R, Takayanagi T, Fujimoto Y, Murata K, Mano Y, Horikawa H, Chuma T. The relationship between trinucleotide repeat length and phenotypic variation in Machado-Joseph disease. J Neurol Sci. 1996a;139:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura R, Takayanagi T, Murata K, Futamura N, Hirano M, Ueno S. Relationship between (CAG)n C configuration to repeat instability of the Machado-Joseph disease gene. Hum Genet. 1996b;98:643–645. doi: 10.1007/s004390050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller VM, Xia H, Marrs GL, Gouvion CM, Lee G, Davidson BL, Paulson HL. Allele-specific silencing of dominant disease genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Jun 10;100(12):7195–200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231012100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monoi H, Futaki S, Kugimiya S, Minakata H, Yoshihara K. Poly-L-glutamine forms cation channels: relevance to the pathogenesis of the polyglutamine diseases. Biophys J. 2000;78:2892–2899. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(00)76830-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley ML, Benzow KA, Schut LJ, Bird TD, Gomez CM, Barkhaus PE, Blindauer KA, Labuda M, Pandolfo M, Koob MD, Ranum LP. Incidence of dominant spinocerebellar and Friedreich triplet repeats among 361 ataxia families. Neurology. 1998;51:1666–1671. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005 Jan;6(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz E, Rey MJ, Mila M, Cardozo A, Ribalta T, Tolosa E, Ferrer I. Intranuclear inclusions, neuronal loss and CAG mosaicism in two patients with Machado-Joseph disease. J Neurol Sci. 2002 Aug 15;200(1-2):19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Yamaguchi S, Kawakami H, Imon Y, Maruyama H, Sakai T, Kazuta T, Ohtake T, Nishimura M, Saida T, Chiba S, Oh-I T, Nakamura S. Characteristic magnetic resonance imaging findings in Machado-Joseph disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:33–37. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicastro G, Menon RP, Masino L, Knowles PP, McDonald NQ, Pastore A. The solution structure of the Josephin domain of ataxin-3: structural determinants for molecular recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Jul.102(30):10493–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501732102. Epub 2005 Jul 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nihiyama K, Murayama S, Goto J, Watanabe M, Hashida H, Katayama S, Numura Y, Nakamura S, Kanazawa I. Regional and cellular expression of the Machado-Joseph disease gene in brains of normal and affected individuals. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:776–781. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera O, Idezuka J, Igarashi S, Takiyama Y, Endo K, Takano H, Oyake M, Tanaka H, Inuzuka T, Hayashi T, Yuasa T, Ito J, Miyatake T, Tsuji S. Progressive atrophy of cerebellum and brainstem as a function of age and size of the expanded CAG repeats in the MJD1 gene in Machado-Joseph Disease. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:288–296. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padiath QS, Srivastava AK, Roy S, Jain S, Brahmachari SK. Identification of a novel 45 repeat unstable allele associated with a diseasephenotype at the MJD1/SCA3 locus. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005 Feb 5;133(1):124–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson HL, Das SS, Crino PB, Perez MK, Patel SC, Gotsdiner D, Fischbeck KH, Pittman RN. Machado-Joseph disease gene product is a cytoplasmic protein widely expressed in brain. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:453–462. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson HL, Perez MK, Trottier Y, Trojanowski JQ, Subramony SH, Das SS, Vig P, Mandel JL, Fischbeck KH, Pittman RN. Intranuclear inclusions of expanded polyglutamine protein in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Neuron. 1997;19:333–344. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80943-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MK, Paulson HL, Pendse SJ, Saionz SJ, Bonini NM, Pittman RN. Recruitment and the role of nuclear localization in polyglutamine-mediated aggregation. J Cell Biology. 1998;143:1457–1470. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez KP, Paulson HL, Pittman RN. Ataxin-3 with an altered conformation that exposes the polyglutamine domain is associated with the nuclear matrix. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2377–2385. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranum LPW, Lundgren JK, Schut LJ, Ahrens MJ, Perlman S, Aita J, Bird TD, Gomez C, Orr HT. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 and Machado-Joseph disease: incidence of CAG expansions among adult-onset ataxia patients from 311 families with dominant, recessive or sporadic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:603–608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Poirier MA. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med. 2004 Jul;10(Suppl):S10–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rub U, Brunt ER, de Vos RA, Del Turco D, Del Tredici K, Gierga K, Schultz C, Ghebremedhin E, Burk K, Auburger G, Braak H. Degeneration of the central vestibular system in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3(SCA3) patients and its possible clinical significance. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004 Aug.4:402–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rub U, Brunt ER, Gierga K, Schultz C, Paulson H, de Vos RA, Braak H. The nucleus raphe interpositus in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (Machado-Joseph disease). J Chem Neuroanat. 2003 Feb;25(2):115–27. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(02)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rub U, Burk K, Schols L, Brunt ER, de Vos RA, Diaz GO, Gierga K, Ghebremedhin E, Schultz C, Del Turco D, Mittelbronn M, Auburger G, Deller T, Braak H. Damage to the reticulotegmental nucleus of the pons in spinocerebellar ataxiatype 1, 2, and 3. Neurology. 2004 Oct 12;63(7):1258–63. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140498.24112.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rub U, de Vos RA, Brunt ER, Schultz C, Paulson H, Del Tredici K, Braak H. Degeneration of the external cuneate nucleus in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (Machado-Joseph disease). Brain Res. 2002 Oct 25;953(1-2):126–34. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rub U, de Vos RA, Schultz C, Brunt ER, Paulson H, Braak H. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (Machado-Joseph disease): severe destruction ofthe lateral reticular nucleus. Brain. 2002 Sep;125(Pt 9):2115–24. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein C, Leggo J, Coetzee GA, Irvine RA, Buckley M, Ferguson-Smith A. Sequence variation and size ranges of CAG repeats in the Machado-Joseph disease, spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 and androgen receptor genes. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1585–1590. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.9.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem Q, Choudhry S, Mukerji M, Bashyam L, Padma MV, Chakravarthy A, Maheshwari MC, Jain S, Brahmachari SK. Molecular analysis of autosomal dominant hereditary ataxias in the Indian population: high frequency of SCA2 and evidence for a common founder mutation. Hum Genet. 2000;106:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s004390051026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Wakisaka A, Fukazawa T, Iwabuchi K, Hamada T, Takada A, Mukai E, Matsuura T, Yoshiki T, Tashiro K. CAG repeat expansion of Machado-Joseph disease in the Japanese: analysis of the repeat instability for parental transmission, and correlation with disease phenotype. J Neurol Sci. 1995;133:128–133. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel H, Tomiuk S, Hofmann K. Elucidation of ataxin-3 and ataxin-7 function by integrative bioinformatics. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2845–2852. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzinger E, Lurz R, Turmaine M, Mangiarini L, Hollenbach B, Hasenbank R, Bates GP, Davies SW, Lehrach H, Wanker EE. Huntingtin-encoded polyglutamine expansions form amyloid-like protein aggregates in vitro and in vivo. Cell. 1997 Aug 8;90(3):549–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Landwehrmeyer B, Schmitt I, Trottier Y, Auburger G, Laccone F, Klockgether T, Volpel M, Epplen JT, Schols L, Riess O. An isoform of ataxin-3 accumulates in the nucleus of neuronal cells in affected brain regions of SCA 3 patients. Brain Path. 1998;8:669–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Lindenberg KS, Krebs A, Schols L, Laccone F, Herms J, Rechsteiner M, Riess O, Landwehrmeyer GB. Protein surveillance machinery in brains with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: redistribution and differential recruitment of 26S proteasome subunits and chaperones to neuronal intranuclear inclusions. Ann Neurol. 2002 Mar;51(3):302–10. doi: 10.1002/ana.10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt I, Evert BO, Khazneh H, Klockgether T, Wuellner U. The human MJD gene: genomic structure and functional characterization of the promoter region. Gene. 2003 Sep 18;314:81–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schols L. Machado-Joseph disease mutation as the genetic basis of most spinocerebellar ataxias in Germany. J Neurol Neurosurg. and Psychiatry. 1995;59:49–50. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.59.4.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schols L, Amoiridis G, Epplen JT, Langkafel M, Przuntek H, Riess O. Relations between genotype and pheotype in German patients with the Machado-Joseph disease mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61:466–470. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schols L, Haan J, Riess O, Amoiridis G, Przuntek H. Sleep disturbance in spinocerebellar ataxias. Is the SCA3 mutation a cause of restless legs syndrome? Neurology. 1998;51:1603–1607. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeiros J, Coutinho P. Epidemiology and clinical aspects of Machado-Joseph disease. Adv Neurol. 1993;61:139–53. Review. No abstract available. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira I, Lopes-Cendes I, Kish S, Maciel P, Gaspar C, Coutinho P, Botez MI, Teive H, Arruda W, Steiner CE, Pinto-Junior W, Maciel JA, Jerin S, Sack G, Andermann E, Sudarsky L, Rosenberg R, MacLeod P, Chitayat D, Babul R, Sequeiros J, Rouleau GA. Frequency of spinocerebellar ataxia type I, dentatorubrual-pallidoluysian atrophy and Machado-Joseph disease mutations in a large group of spinocerebellar ataxia patients. Neurology. 1996;46:214–218. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira I, Miranda C, Guimaraes L, Moreira MC, Alonso I, Mendonca P, Ferro A, Pinto-Basto J, Coelho J, Ferreirinha F, Poirier J, Parreira E, Vale J, Januario C, Barbot C, Tuna A, Barros J, Koide R, Tsuji S, Holmes SE, Margolis RL, Jardim L, Pandolfo M, Coutinho P, Sequeiros J. Trinucleotide repeats in 202 families with ataxia: a small expanded (CAG)n allele at the SCA17 locus. Arch Neurol. 2002 Apr;59(4):623–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong BW, Cheng CH, Liu RS, Shan DE. Machado-Joseph disease: Clinical, molecular, and metabolic characterization in Chinese kindreds. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:446–452. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong BW, Lin KP. An electrophysiologic and pathologic study of peripheral nerves in individuals with Machado-Joseph disease. Chin Med. 1998;61:181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong B, Lu Y, Choo K, Lee H. Frequency Analysis of Autosomal Dominant Cerebellar Ataxias in Taiwanese Patients and Clinical and Molecular Characterization of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 6. Arch Neurology. 2001;58:1105–1109. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.7.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanin G, Cancel G, Durr A, Chneiweiss H, Dubourg O, Weissenbach J, Cann HM, Agid Y, Brice A. The gene for spinal cerebellar ataxia 3 (SCA3) is located in a region of 3 cM on chromosome 14q24.3-q32.2. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:193–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey E, du Sart D, Shaw J, Lorentzos P, Kelly L, McKinley Gardner RJ, Forrest SM, Biros I, Nicholson GA. Frequency of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Types 1,2,3,6, and 7 in Australian Patients with Spinocerebellar Ataxia. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000;95:351–357. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001211)95:4<351::aid-ajmg10>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramony SH, Currier RD. Intrafamilial variability in Machado-Joseph disease. Movement Disorders. 1996;11:741–743. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramony SH, Hernandez D, Adam A, Smith-Jefferson S, Hussey J, Gwinn-Hardy K, Lynch T, McDaniel O, Hardy J, Farrer M, Singleton A. Ethnic differences in the expression of neurodegenerative disease:Machado-Joseph disease in Africans and Caucasians. Mov Disord. 2002 Sep;17(5):1068–71. doi: 10.1002/mds.10241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsky L, Coutinho P. Machado-Joseph disease. Clin Neurosci. 1995;3(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga T, Matsushima H, Nakamura S, Akiguchi I, Kimura J. Ubiquitin-immunoreactive inclusions in anterior horn cells and hypoglossal neurons in a case with Joseph's disease. Acta Neuropath. 1993;85:341–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00227732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugars KL, Rubinsztein DC. Transcriptional abnormalities in Huntington disease. Trends Genet. 2003;19:233–238. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00074-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait D, Riccio M, Sittler A, Scherzinger E, Santi S, Ognibene A, Maraldi NM, Lehrach H, Wanker EE. Ataxin-3 is transported into the nucleus and associates with the nuclear matrix. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:991–997. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano H, Cancel G, Ikeuchi T, Lorenzetti D, Mawad R, Stevanin G, Didierjean O, Durr A, Oyake M, Shimohata T, Sasaki R, Koide R, Igarashi S, Hayashi S, Takiyama Y, Nishizawa M, Tanaka H, Zoghbi HY, Brice A, Tsuji S. Close association between prevalence of dominantly inherited spinocerebellar ataxias with CAG-repeat expansions and frequencies of large normal CAG alleles in Japanaese and Caucasian populations. Amer J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1060–1066. doi: 10.1086/302067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiyama Y, Igarashi S, Rogaeva EA, Endo K, Rogaev EI, Tanaka H, Sherrington R, Sanpei K, Liang Y, Saito M, Tsuda T, Takano H, Ikeda M, Lin C, Chi H, Kennedy JL, Lang AE, Wherrett JR, Segawa M, Nomura Y, Yuasa T, Weissenbach J, Yoshida M, Nishizawa M, Kidd KK. Evidence for intergenerational istability in the CAG repeat in the MJD1 gene and for conserved haplotypes at flanking markers amongst Japanese and Caucasian subjects with Machado-Joseph disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1137–1146. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.7.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiyama Y, Okynagi S, Kawashima S, Sakamoto H, Saito K, Yoshida M, Tsuji S, Mizuno Y, Nishizawa M. A clinical and pathologic study of a large Japanese family with Machado-Joseph disease tightly linked to the DNA markers on chromosome 14q. Neurology. 1994;44:1302–1308. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.7.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiyama Y, Sakoe K, Nakano I, Nishizawa M. Machado-Joseph disease: Cerebellar ataxia and autonomic dysfunction in a patient with the shortest known expanded allele (56 CAG repeat units) of the MJD1 gene. Neurology. 1997;49:604–606. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiyama Y, Shimazaki H, Morita M, Soutome M, Sakoe K, Esumi E, Muramatsu SI, Yoshida M. Maternal anticipation in Machado-Joseph disease (MJD); some maternal factors independent of the number of CAG repeat units may play a role in genetic anticipation in a Japanese MJD family. J Neurological Sciences. 1998;155:141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JP, Hardy J, Fischbeck KH. Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science. 2002;296:1991–1995. doi: 10.1126/science.1067122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulouse A, Au-Yeung F, Gaspar C, Roussel J, Dion P, Rouleau GA. Ribosomal frameshifting on MJD-1 transcripts with long CAG tracts. Hum Mol Genet. 2005 Sep 15;14(18):2649–60. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi299. Epub 2005 Aug 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier Y, Cancel G, An-Gourfinkel I, Lutz Y, Weber C, Brice A, Hirsch E, Mandel JL. Heterogeneous intracellular localization and expression of ataxin-3. Neurobiol. Dis. 1998;5:335–47. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HF, Liu CS, Leu TM, Wen FC, Lin SJ, Liu CC, Yang DK, Li C, Hsieh M. Analysis of trinucleotide repeats in different SCA loci in spinocerebellar ataxia patients and in normal population of Taiwan. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004a May;109(5):355–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HF, Tsai HJ, Hsieh M. Full-length expanded ataxin-3 enhances mitochondrial-mediated cell death and decreases Bcl-2 expression in human neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004b Nov 26;324(4):1274–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuite PJ, Rogaeva EA, St George-Hyslop PH, Lang AE. Dopa-responsive parkinsonism phenotype of Machado-Joseph disease: confirmation of 14q CAG expansion. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:684–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchihara T, Iwabuchi K, Funata N, Yagishita S. Attenuated nuclear shrinkage in neurons with nuclear aggregates--a morphometricstudy on pontine neurons of Machado-Joseph disease brains. Exp Neurol. 2002 Nov;178(1):124–8. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Alfen N, Sinke R, Zwarts M, Gabreels-Festen A, Praamstra P, Kremer BP, Horstink MW. Intermediate CAG repeat lengths (53,54) for MJD/SCA3 are associated with an abnormal phenotype. Annals of Neurology. 2001;49:805–808. doi: 10.1002/ana.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman P, Wetzel R, Tanaka M, Nukina N, Goldberg AL. Eukaryotic proteasomes cannot digest polyglutamine sequences and release them during degradation of polyglutamine-containing proteins. Mol Cell. 2004;14:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Keiko I, Nukina N, Goto J, Ichikawa Y, Uchida K, Sakamoto T, Kanazawa I. Machado-Joseph Disease gene product identified in lymphocytes and brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:476–479. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrick JM, Chan HY, Gray-Board GL, Chai Y, Paulson HL, Bonini NM. Suppression of polyglutamine-mediated neurodegeneration in Drosophila by the molecular chaperone HSP70. Nat Genet. 1999;23:425–428. doi: 10.1038/70532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]