Abstract

Clinical diagnostic tests based on nucleic acid amplification assist with the prompt diagnosis of microbial infections because of their speeds and extremely low limits of detection. However, the design of appropriate internal controls for such assays has proven difficult. We describe a reaction-specific RNA internal control for diagnostic reverse transcription (RT)-PCR which allows extraction, RT, amplification, and detection to be monitored. The control consists of a G+C-rich (60%) RNA molecule with an extensive secondary structure, based on a modified hepatitis delta virus genome. The rod-like structure of this RNA, with 70% intramolecular base pairing, provides a difficult template for RT-PCR. This ensures that the more favorable target virus amplicon is generated in preference to the control, with the control being detected only if the target virus is absent. The unusual structure of hepatitis delta virus RNA has previously been shown to enhance its stability and resistance to nucleases, an advantage for routine use as an internal control. The control was implemented in three nested multiplex RT-PCRs to detect nine clinically important respiratory viruses: (i) influenza A and B viruses, (ii) respiratory syncytial viruses A and B and human metapneumovirus, and (iii) parainfluenza virus types 1 to 4. The detection limits of these assays were not detectably compromised by the presence of the RNA control. During routine testing of 324 consecutive unselected respiratory samples, the presence of the internal control ensured that genuine and false-negative results were distinguishable, thus increasing the diagnostic confidence in the assay.

Over the last decade, PCR has permitted the rapid, accurate detection of many pathogens, even when the pathogens are present in low numbers. The promptness of this approach has been shown to be clinically useful for both making a positive diagnosis and ruling out infection (11). Commercially produced diagnostic kits are available for relatively few pathogens; hence, many in-house assays that use both gel-based and real time detection systems have been developed for the detection of additional targets (20). Such assays are economical, but they generally omit reaction-specific internal controls to monitor the extraction, reverse transcription (RT), amplification, and detection steps. This is due to the technical difficulty of designing and implementing robust internal controls. Such controls allow negative results due to inhibition or human error to be distinguished from true-negative results, increasing confidence in the technique.

An internal control for diagnostic RT-PCR assays should ideally have the following characteristics. It should be straightforward and economical to produce and standardize and should have sufficient stability for routine storage and use. Its sequence should be absent from clinical samples, and the control preparation should be noninfectious. It should be suitable for many different assays, the results of which should be simple to interpret. Few (if any) internal controls described to date have all of these features.

Several groups have designed competitive DNA and RNA internal controls, with the same primer pair used to detect both the control and the target microbe. The two amplicons were then differentiated by size or by the use of heterologous probes (1, 4, 18, 23, 26). A method for the production of competitive RNA controls that proved useful for the identification of RT-PCR inhibitors has been described (13). However, if the same primers are used to detect both the control and the target amplicons, the overall detection limit of the assay may be compromised, especially if the target microbe is present at low levels. Competitive controls are incompatible with multiplex PCR in which several primer pairs are required. Multiplex PCR is attractive for molecular diagnostics since multiple pathogens producing similar symptoms can be screened for simultaneously in a single reaction.

Noncompetitive internal controls have also been described, with separate primer pairs used to detect the control and the microbe(s) of interest. Such controls often comprise endogenous RNA or DNA in the sample, for example, β-actin or 18S rRNA (24). Unfortunately, the concentrations of these RNAs vary widely among clinical samples. Alternatively, a clinical sample may be spiked with a known amount of an animal virus such nonhuman seal herpes virus type 1 (DNA) or phocine distemper virus (RNA) (20, 27). Although attractive, the use of live viruses as internal controls may raise issues of safety and consistency between preparations. Positive controls for various RT-PCR assays have been developed commercially (Armored RNA; Ambion [Europe Ltd.], Huntingdon, United Kingdom). These consist of an RNA fragment assembled into phage-like particles (7, 21). This technology has also been adapted to provide an internal control for a real-time PCR assay (6). Their cost and a lack of versatility have so far prevented the widespread adoption of Armored RNA controls.

A significant number of the many RT-PCR assays described to date are for respiratory viruses. These pathogens cause a considerable burden of illness, particularly during the winter. Since different viruses often cause similar symptoms, appropriate patient management can be assisted by rapid laboratory tests with a low limit of detection. Respiratory viruses have traditionally been detected by cell culture and more recently by commercially available direct immunofluorescence tests. RT-PCR is faster and more sensitive than cell culture and offers greater sensitivity than immunofluorescence (9, 25, 28). The aims of the present study were twofold: (i) to identify an RNA molecule suitable for routine use as a universal reaction-specific internal control and (ii) to include the control in a routine assay for nine clinically important respiratory viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

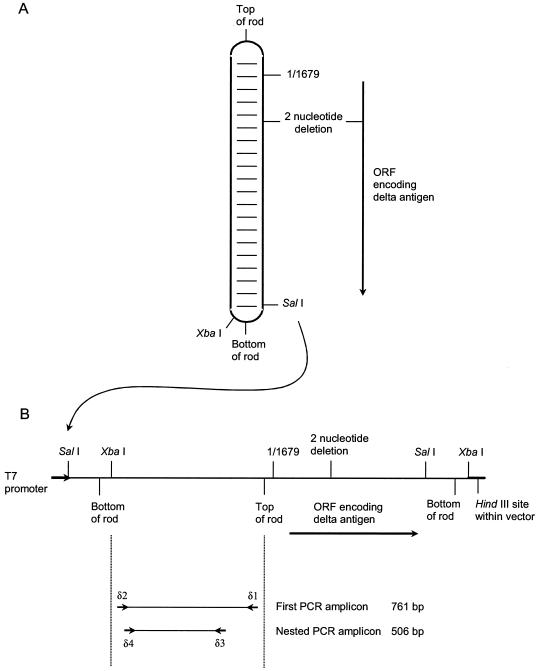

Construction of plasmid pTW107.

Plasmid pTW107 was constructed in vector pGem3z (Promega UK, Southampton, United Kingdom). It contained 1.2 copies of a modified hepatitis delta virus (HDV) genome flanked by the T7 and SP6 promoters within the vector. The HDV sequence extended from the SalI restriction site at nucleotide positions 962 to 967 (the numbering is as described elsewhere [15]) through the remaining full length of the genome, ending at the XbaI restriction site (nucleotide positions 781 to 786) of the second genome (Fig. 1). The construct contained a 2-nucleotide deletion at positions 1435 to 1436 within the open reading frame encoding the delta antigen, rendering the RNA incapable of autonomous replication.

FIG. 1.

Modified HDV genome used as an internal control. (A) Representation of the predicted rod-like secondary structure of the HDV genome; (B) linear representations of the sequence used for in vitro transcription of the control RNA (1.2 copies of the genome) and the PCR amplicons used as internal controls. The sequences of vector pTW107, including the sequences of the T7 promoter and the HindIII site used to linearize the vector, are shown as heavier lines. ORF, open reading frame.

In vitro transcription of modified HDV RNA and removal of DNA template.

pTW107 was linearized with the restriction enzyme HindIII. HDV RNA (genomic sense) was transcribed in vitro from the T7 promoter by using a commercially available kit (Megascript T7 transcription kit; Ambion [Europe Ltd.]) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The template plasmid DNA was removed by incubation with DNase I (Ambion [Europe Ltd.]) at 37°C for 15 min. Further precautions were taken to remove the template DNA by extraction with Tri reagent LS (Sigma Aldrich Company Ltd., Gillingham, United Kingdom) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The resultant RNA pellet was resuspended in RNA storage solution (Ambion [Europe Ltd.]). Its integrity was confirmed by electrophoresis through a 1% formaldehyde 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid gel containing ethidium bromide. Aliquots of RNA for single use (50 μl of a concentration of 100 fg/μl) during extraction of one batch of clinical samples were stored at −80°C. Further (100× concentrated) stocks of 10 pg/μl were stored similarly. Additional dried RNA pellets were placed under absolute ethanol for long-term storage.

Application of internal control to three multiplex nested RT-PCR assays for nine respiratory viruses. (i) Coextraction of internal control and RNA from clinical samples.

Clinical samples including nasopharyngeal aspirates, throat and nasal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage samples, samples from endotracheal tips, and lung biopsy specimens were diluted by the addition of 1 to 5 ml of virus transport medium (depending on the specimen volume). Further disruption of the biopsy tissue was not performed, as the tissue had been stored in the virus transport medium for several days and sufficient virus for detection was present in the medium. Cellular debris was removed from all specimens by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm in an Eppendorf 5415D benchtop centrifuge for 5 min. Total RNA was extracted from the supernatant by use of a silica column-based kit (Viral RNA mini kit; Qiagen Ltd., Crawley, United Kingdom) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, with the following modifications. Prior to RNA extraction, 1 μl of 100 fg of modified HDV RNA (internal control) per μl was added to 280 μl of AVL extraction buffer (Qiagen Ltd.). This was followed by the addition of 69 μl of respiratory sample supernatant. The RNA was eluted from the column in 40 μl of AVE buffer (Qiagen Ltd.).

(ii) cDNA synthesis.

RT was performed in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 10.5 μl of RNA and 0.5 μl (250 ng) of random hexamers (Promega UK). This was denatured at 70°C for 10 min, followed by immediate transfer to ice, on which the remainder of the reaction mixture was assembled: 4 μl of the first-strand buffer (Invitrogen Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom), 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol (Invitrogen Ltd.), 1 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (10 mM; Invitrogen Ltd.), 1 μl of RNAsin (Promega UK), and 1 μl of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Ltd.). Incubation was at 37°C for 1 h, followed by inactivation at 70°C for 10 min.

(iii) PCR amplification.

The oligonucleotide primers used are shown in Table 1. For each first round of amplification, the 50-μl PCR mixture contained 5 μl of cDNA, 5 μl of 10× Hotstar Taq DNA polymerase reaction buffer (Qiagen Ltd.) containing 15 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of the oligonucleotide primer mixture (containing each target virus primer at 10 μM and the internal control primers at 5 μM), 1 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 0.25 μl (1.25 U) of Hotstar Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen Ltd.). For the second-round nested amplification reaction, the mixture (50 μl) included 1 μl of the product of the first PCR as template and an additional 3 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 (final concentration, 4 mM). The following amplification conditions were used: denaturation and enzyme activation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 20 s, annealing at 55°C for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s in the first PCR or 30 s in the nested PCR, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used in the three internally controlled, nested multiplex PCRs to detect nine respiratory virusesa

| Target virus | First-round primer | First-round primer sequence | Second-round primer | Second-round primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | FluA-1 | TGGATGGCATGCCATTCTGC | FluA-3 | ACCAGGAGTGGAGGAAACAC |

| FluA-2 | GCATTGTCTCCGAAGAAATAAG | FluA-4 | AGAAATAAGATCCTTCATTACTC | |

| Influenza B | FluB-1 | GAGGGCTATTGAGAGACATC | FluB-3 | ATATGGCAACACCTGTTTCC |

| FluB-2 | GTCATTCATCATCTTGAGTAG | FluB-4 | TGACATCTGCATCACGTCC | |

| PIV-1 | PIV1-1 | CCTTAAATTCAGATATGTATCCTG | PIV1-3 | CCGGTAATTTCTCATACCTATG* |

| PIV1-2 | GTTATCTTAAGAGCATCATTGC | PIV1-4 | CCTTGGAGCGGAGTTGTTAAG | |

| PIV-2 | PIV2-1 | AACAATCTGCTGCAGCATTT* | PIV2-3 | CCATTTACCTAAGTGATGGAAT* |

| PIV2-2 | ATGTCAGACAATGGGCAAAT* | PIV2-4 | GCCCTGTTGTATTTGGAAGAGA* | |

| PIV-3 | PIV3-1 | AACTCAGACTTGGTACCTGAC | PIV3-3 | ATCTGTTGGACCAGGGATATAC |

| PIV3-2 | TGAGTTTAAGCC (C/T) TTGTCAAC | PIV3-4 | GACACCCAGTTGTGTTGCAG | |

| PIV-4 | PIV4-1 | CTGAACGGTTGCATTCAGGT* | PIV4-3 | AAAGAATTAGGTGCAACCAGTC* |

| PIV4-2 | TTGCATCAAGAATGAGTCCT* | PIV4-4 | GTGTCTGATCCCATAAGCAGC* | |

| RSV A | RSV-AB1 | CTGTCATCCAGCAAATACAC | RSV-A3 | AACACATCAATAAGTTATGTGGC |

| RSV-AB2 | CATAGGCATTCATAAA (C/T) AATCC | RSV-A4 | CAATCAGGAGAGTCATGCCTG | |

| RSV B | RSV-AB1 | As RSV A | RSV-B3 | AACACCTAAACAAACTATGTGG |

| RSV-AB2 | RSV-B4 | ACTTGTATTTCTGATGTCAAGC | ||

| HuMV | HuMV-1 | GCTTCAGTCAATTCAACAGAAG | HuMV-3 | TGCGGCA (A/G) TTTTCAGACAATGC |

| HuMV-2 | TCCTGTGCT (G/A) ACTTTGCATGG | HuMV-4 | GATATGTTGATGTTGCA (C/T) TC | |

| Internal control | Delta-1 | CCAAGTTCCGAGCGAGGAG | Delta-3 | GTTGAGTAGCACTCAGAGG |

| Delta-2 | CCCATTCGCCATTACCGAG | Delta-4 | CATTACCGAGGGGACGGTC |

All primers are shown in the 5′ to 3′ direction. Primers 1 and 2 were used in the first amplification reaction, and primers 3 and 4 were used in the second, nested amplification. Forward primers are indicated by odd numbers, and reverse primers are indicated by by even numbers. Nucleotide positions where a degenerate sequence was used are indicated in parentheses. Asterisks indicate primers which were described previously (2). Other primers modified slightly from this study included PIV1-1, which is primer Pip1+ with a 3′ extension, and PIV1-4, which is PiS1 with a modified 5′ sequence.

Preparation of plasmid DNA for establishment of assay detection limits and use as positive controls.

The PCR amplicons generated during the first amplification round with each target virus were ligated directly to the vector pGemT easy (Promega UK), and electrocompetent Escherichia coli cells were transformed. Colonies containing plasmid DNA with the required insert were identified by PCR, and DNA was prepared by the miniprep procedure (Spin miniprep kit; Qiagen Ltd.). The optical density at 260 nm of each plasmid solution was determined, and stock solutions containing 1010 molecules of plasmid DNA per μl were prepared by use of Avogadro's number. For each plasmid a 10-fold dilution series from 1010 to 10−2 molecules per μl was made and was used to determine the detection limit of the PCRs. These plasmids were also used to prepare positive control mixtures, one for each of the three multiplex assays. The positive control plasmids were coamplified, providing a single-tube positive control for each of the three assays. As a precaution against contamination, the positive control plasmids were prepared in a separate laboratory on a floor different from the floor of the laboratory where the diagnostic RT-PCRs were carried out.

RESULTS

Choice of RNA internal control molecule.

The HDV genome was identified as an unusual RNA molecule which could be used as a reaction-specific internal control in RT-PCR assays. The HDV genome is 1,679 nucleotides in length, and its G+C-rich (60%) RNA forms a rod-like structure with 70% intramolecular base pairing (14, 29). This unusual secondary structure was central to its choice as an internal control. It enhances stability during freezing-thawing, increases resistance to nucleases (3), and renders the molecule a difficult template for RT-PCR. The last feature was intended to ensure preferential amplification of the target virus amplicons, thus maintaining a low limit of detection (1 to 10 target molecules) for the viruses of interest.

In vitro transcription of HDV internal control RNA.

Plasmid pTW107, which contained 1.2 copies of a modified HDV genome, was constructed with a 2-nucleotide deletion in the open reading frame encoding the delta antigen (Fig. 1). This safety consideration rendered the RNA transcribed from the plasmid incapable of replication (5, 16). After transcription, the integrity of the RNA was confirmed by gel electrophoresis and it was standardized by use of a spectrophotometer. The number of molecules present was calculated by use of Avogadro's number. RNA hydrolysis was minimized by storage at −80°C in sodium citrate solution (RNA storage solution; Ambion [Europe Ltd.]).

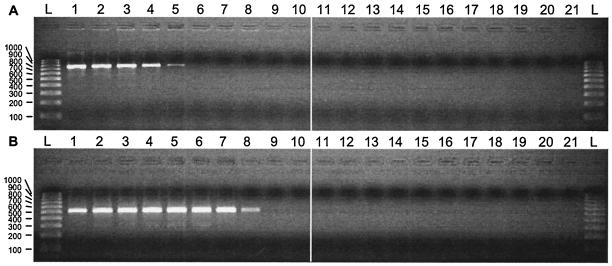

To confirm that the control RNA was free of contaminating plasmid DNA, a 10-fold dilution series of the RNA (0.1 μg/μl to 0.1 fg/μl) was made. Each aliquot was extracted as a clinical sample, and the RNA was divided into two. Half was used for cDNA synthesis and the other was stored on ice prior to amplification. All aliquots were then amplified by nested PCR with primers delta-1 and delta-2 in the first round (Fig. 2A) and primers delta-3 and delta-4 in the second round (Fig. 2B). These primers were designed from one side of the predicted rod-like structure of the HDV genome (Fig. 1B; Table 1). The detection limit after the first PCR amplification corresponded to the 10-pg RNA dilution, and that after the nested PCR corresponded to 10 fg. The latter corresponds to approximately 10,800 RNA molecules. No residual plasmid DNA was detected under these conditions in the RNA lacking RT.

FIG. 2.

Detection of in vitro-transcribed HDV control RNA by RT-PCR and confirmation that the DNA plasmid template was efficiently removed. (A) Lanes 1 to 10, RT-PCR amplification products from a 10-fold serial dilution of in vitro-transcribed HDV RNA. The dilution series extended from 0.1 μg of RNA per RT-PCR mixture in lane 1 to 0.1 fg in lane 10. The amplification primers were delta-1 and delta-2, which gave a product of 761 bp. Lanes 11 to 20, as for lanes 1 to 10, but without RT of the template RNA to detect any contaminating plasmid template DNA; lane 21, negative control; lane L, 1-kb ladder (Bio-Rad). Sizes (in base pairs) are indicated on the left. A total of 10 μl of each 50-μl PCR mixture was analyzed. (B) As for panel A, but showing the amplification products of a nested PCR performed with the templates described in the legend to panel A and primers delta-3 and delta-4 to obtain a product of 506 bp. The detection limit is shown in lane 8 and is 10 fg of RNA, which corresponds to approximately 10,800 molecules of RNA added to the extract.

When Q solution (a PCR additive which relaxes secondary structure and assists with the amplification of G+C-rich templates; Qiagen Ltd.) was included in the PCR mixture, the detection limit of the HDV cDNA increased 100-fold. To ensure that the amplification of the internal control remained suboptimal compared to that of the target viruses, Q solution was not used in the PCR assays. As 100 fg of RNA was detected reproducibly by the nested PCR, this concentration was used as an internal control in routine RT-PCR assays.

Internally controlled assay for nine respiratory viruses.

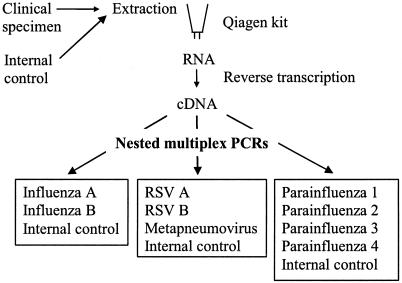

The nine viruses used in this study were chosen on the basis of clinical need and potential benefits for patient management. They were influenza A and influenza B viruses, respiratory syncytial virus type A (RSV A), RSV B, human metapneumovirus (HuMV), and parainfluenza virus types 1 to 4 (PIV-1 to PIV-4, respectively). Although RT-PCR assays for these viruses have been described previously, the assays were incompatible with the HDV internal control due to the amplicon sizes and/or the oligonucleotide primer design. Furthermore, our aim was to detect all nine viruses in three nested multiplex RT-PCRs (Fig. 3) by using one cDNA synthesis reaction followed by identical thermocycling conditions. This would simplify the routine use of the assay. New multiplex assays were therefore designed incorporating the internal control.

FIG. 3.

Overview of the internally controlled nested multiplex RT-PCR assay for the detection of nine respiratory viruses.

The viral genes chosen as targets were selected on the basis of the facts that (i) they included highly conserved nucleotide sequences, (ii) sequences from a large number of representative strains were available in public databases (GenBank and the Los Alamos Influenza Sequence Database [http://www.flu.lanl.gov]), and (iii) they had been amplification targets in previously published assays (Table 2) (10, 19, 22, 25). New primers were designed for six of the nine target viruses. The exceptions were the primers for PIV-2 and PIV-4, primers for which were published previously (2), and the primers for PIV-1, which were modified slightly from those used in a previous study (2). The primers for the internal control were designed to amplify a DNA fragment larger than all the target virus amplicons to enhance the preferential amplification of the latter.

TABLE 2.

Virus genes targeted in nested multiplex RT-PCRs to detect the nine respiratory viruses

| Round | Size (bp) of amplicon obtained in the following assay:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza virus

|

RSV and HuMV

|

PIV

|

||||||||

| Controla | Influenza A virus nucleo- capsid | Influenza B virus nucleo- capsid | RSV A nucleo- capsid | RSVB nucleo- capsid | HuMV F protein | PIV-1 hemagglutinin- neuraminidase | PIV-2 hemagglutinin- neuraminidase | PIV-3 hemagglutinin- neuraminidase | PIV-4 phospho- protein | |

| First | 761 | 490 | 722 | 702 | 702 | 526 | 362 | 506 | 477 | 441 |

| Second | 506 | 296 | 402 | 343 | 251 | 454 | 316 | 203 | 109 | 246 |

The control amplicon was designed to be larger then than all the virus amplicons in both rounds of the nested PCR.

Assay verification by amplification of known positive samples and limit of detection.

First, the abilities of the nested PCR primers to detect each target respiratory virus were confirmed by using cDNA synthesized from an infected cell culture supernatant. Amplicons were produced by using the first-round and nested PCR primer pairs in separate single rounds of PCR to confirm successful amplification of each virus by both primer pairs. A cell culture supernatant was not available for PIV-4, but the primers for this virus were validated previously (2), and the amplicons from PIV-4 later obtained with clinical samples were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

Second, the sequences chosen for primer design were confirmed to be conserved among isolates and to be genetically stable over time. A total of 191 isolates obtained up to 20 years ago were tested (Table 3). These isolates were contained either in known positive clinical samples (previously identified by direct immunofluorescence, cell culture, or an alternative PCR assay) or in archived cell culture supernatants. A single contradictory result was obtained: a nasopharyngeal aspirate which was previously positive for influenza A virus by cell culture was negative for the virus by PCR. One avian influenza A virus (H7N7) isolated from a human conjunctival swab specimen (17) was detected in an archived, frozen cell culture supernatant by the influenza A virus-specific RT-PCR.

TABLE 3.

PCR primer verificationa

| Virus | Yr | No. of known positive samples tested

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPA | Culture supernatant | Total | ||

| Influenza A virus | 1991-2003 | 33 | 37 | 70 |

| Influenza B virus | 1987-2003 | 10 | 15 | 25 |

| RSV A | 1987-2003 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| RSV B | 1987-2003 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| HuMV | 2002-2003 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| PIV-1 | 1990-2003 | 20 | 2 | 22 |

| PIV-2b | 2001-2003 | 12 | 0 | 12 |

| PIV-3 | 1983-2003 | 28 | 10 | 38 |

| PIV-4b | 2001-2003 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

A total of 191 samples known to contain virus and archived up to 20 years ago were tested to confirm that the PCR primer sequences are genetically conserved among isolates and are stable over time. The positive samples comprised nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) (confirmed to be positive by immunofluorescence, cell culture, or an alternative PCR assay) and cell culture supernatants archived at −80°C for up to 20 years.

The primers were also validated in a previous study (2).

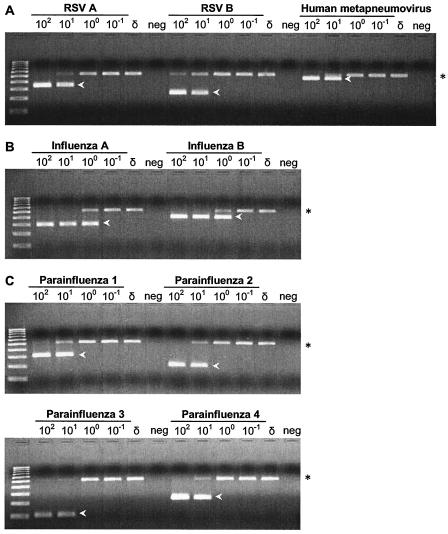

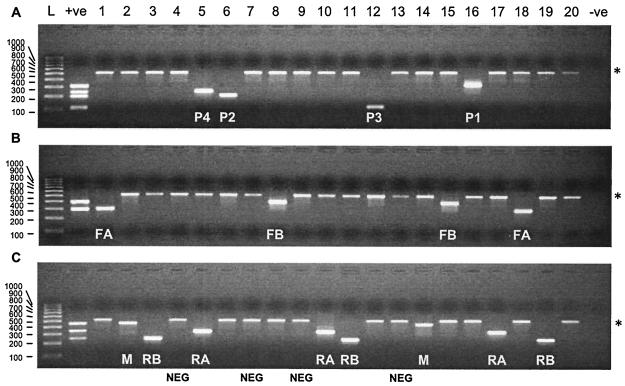

To determine whether the internal control compromised the detection limit of the PCRs, reactions were performed both with and without the control. The template was a 10-fold dilution series of positive control plasmid DNA both with (Fig. 4) and without (data not shown) the internal control (HDV cDNA). No differences in the detection limits of the PCRs were observed whether or not the control was present. As the number of target plasmid molecules increased, the amount of the control amplicon decreased or disappeared. The detection limits were 1 molecule of plasmid DNA per 50 μl of the PCR mixture for influenza A and B viruses and 10 molecules of plasmid DNA for RSV A, RSV B, HuMV, and PIV-1 to PIV-4.

FIG. 4.

The HDV internal control did not compromise the limit of detection of the assay. Nine plasmids containing each of the first-round PCR amplification products were constructed. A dilution series containing 102 to 10−1 molecules of each plasmid per μl was made, and 1 μl of each dilution was amplified in each nested multiplex PCR. (A) RSV A, RSV B, and HuMV; (B) influenza A and B viruses; (C) PIV-1 to PIV-4. To determine whether the HDV internal control compromised the limit of detection, the PCR mixture also contained the HDV internal control cDNA (reverse-transcribed RNA, not plasmid HDV DNA) at the same concentration used in the diagnostic assay. The virus amplicons are indicated by arrowheads, and the HDV control is indicated by asterisks. As the concentration of the plasmid containing the target virus sequences was increased, the yield of the control amplicon decreased or disappeared completely. For comparison, a PCR mixture containing HDV cDNA alone was performed (lanes δ). neg, negative controls lacking target DNA.

Routine detection of respiratory viruses in clinical samples by internally controlled RT-PCR.

A total of 324 respiratory samples taken between 29 October 2002 and 14 April 2003 were available for testing. The samples consisted of nasopharyngeal aspirates (n = 231), throat swabs (n = 33), bronchoalveolar lavage specimens (n = 17), nasal swabs (n = 12), samples from endotracheal tips (n = 11), lung biopsy specimens (n = 8), and others (n = 12). RNA from at least one target virus was detected in 150 samples (46.3%), and the RT-PCR was inhibited by only 2 samples (Table 4). Each of the nine target viruses were identified at least once (Fig. 5 and Table 5). RNA from two different viruses was detected in three specimens (0.1%), indicating coinfections with PIV-4 and RSV A (Fig. 5, lane 5), PIV-3 and RSV B, and PIV-4 and RSV B. When RNA from the target virus was detected, the internal control RNA was not detected (Fig. 5). When a target virus was not detected, detection of the internal control provided confirmation that the assay was performed correctly and that the sample lacked inhibitors.

TABLE 4.

Clinical specimens used for routine clinical testing by the assay

| Clinical specimena | No. of specimens tested | No. of specimens in which:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus was detected | No virus was detected | Inhibition was detected | ||

| NPA | 231 | 128 | 102 | 1 |

| TS | 33 | 4 | 29 | |

| BAL | 17 | 4 | 12 | 1 |

| NS | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| ETT | 11 | 4 | 7 | |

| LB | 8 | 1 | 7 | |

| Others | 12 | 3 | 9 | |

| Total | 324 | 150 | 172 | 2 |

NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirate; TS, throat swab; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage specimen; NS, nasal swab; ETT, endotracheal tip; LB, lung biopsy specimen.

FIG. 5.

Results of screening of 20 respiratory specimens for nine target viruses by internally controlled nested multiplex RT-PCRs. Lanes 1 to 20 each include a single specimen in all three gels. (A) Assay for PIV-1 to PIV-4 (detection of each virus is indicated by P1, P2, P3, and P4, respectively); (B) assay for influenza A and B viruses (the detection of each virus is indicated by FA and FB, respectively); (C) assay for RSV A, RSV B, and HuMV (the detection of each virus is indicated by RA, RB, and M, respectively). A specimen with a dual infection is shown in lane 5. Asterisks, detection of the internal control when target viruses were not detected; lanes L, 1-kb DNA ladder (Bio-Rad); +ve, coamplified positive control plasmid DNA for each of the target viruses, −ve, negative control for contamination; NEG, the specimen is negative for virus.

TABLE 5.

Application of the assay to routine clinical testinga

| Virus | No. of clinical specimens in which virus was detected

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPA | TS | BAL | NS | ETT | LB | Other | Total | |

| Influenza A virus | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Influenza B virus | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | |||

| RSV A | 28 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 32 | |||

| RSV B | 73 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 77 | |||

| HuMV | 8 | 8 | ||||||

| PIV-1 | 0 | |||||||

| PIV-2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| PIV-3 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| PIV-4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||

A total of 324 clinical samples were tested. NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirate; TS, throat swab; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage specimen; NS, nasal swab; ETT, endotracheal tip; LB, lung biopsy specimen.

DISCUSSION

The HDV genome was successfully used as a reaction-specific internal control in routine clinical diagnostic RT-PCRs. Its extensive secondary structure has a self-stabilizing effect which, together with its high G+C content, makes it a difficult template for RT and amplification. HDV RNA is also known to have enhanced resistance to nucleases (3). As a consequence, the RNA was sufficiently stable for routine use and did not compromise the detection limit of the three nested multiplex RT-PCRs in which it was used. The control RNA was modified by the deletion of two nucleotides within the open reading frame encoding the delta antigen, a safety consideration designed to eliminate the ability of the RNA to replicate autonomously (5, 16). The internal control was used in three nested multiplex RT-PCRs for the routine detection of nine respiratory viruses in clinical samples. These three assays were designed to be performed under identical thermocycling conditions with cDNA from a single randomly primed synthesis reaction (Fig. 3). The advantages of this approach to the diagnostic laboratory are an improved ability to interpret assays results due to the presence of the internal control, together with savings in cost and time.

The control RNA was simple to produce and standardize by spectrophotometry. High yields of the control RNA were easily transcribed in vitro, and contaminating plasmid template DNA was not detectable at the concentrations tested in the nested RT-PCRs (Fig. 2). The RNA was stored at −80°C in 100×-concentrated stock solutions (10 pg/μl) and single-use aliquots (100 fg/μl). It proved sufficiently stable during storage for routine use (RNA stored for at least 8 months at −80°C and a 100×-concentrated stock that had undergone two freeze-thaw cycles were tested). The RNA was coextracted with each clinical sample, which provided a control for the extraction, RT, PCR, and detection steps of the assay. The modified HDV sequence may provide a suitable control for other assays based on nucleic acid amplification. Our data suggest that HDV cDNA (a plasmid or linear HDV sequence) may also be used as a suitable control in assays for the detection of pathogens with DNA genomes and that it could also be adapted for use in a real-time PCR.

The HDV genome sequence was absent from the respiratory specimens tested by the assay. However, the control sequence may be present very rarely in certain samples, such as blood from patients with hepatitis B virus infection who are coinfected with HDV. The structural characteristics which make HDV an attractive control are shared by its relatives, the plant viroids (8), which may provide an alternative to HDV. The viroids have much smaller genomes than HDV (246 to 401 nucleotides, compared to 1,700 nucleotides) and could be particularly useful controls for assays based on real-time PCR. It may also prove useful as an internal standard for samples from cell cultures and veterinary samples.

The control RNA was modified by the deletion of two nucleotides within the open reading frame encoding the delta antigen. This renders the HDV RNA incapable of replication (5, 16), which also requires the presence of hepatitis B virus. The control was therefore suitable for routine use, since it is noninfectious. Infectivity may be a possible disadvantage of the routine use of animal viruses as internal controls, (20, 27), and many laboratories lack the facilities for their production. However, animal viruses have the advantage of an intact capsid, providing an authentic control for the protein-disruption phase of the extraction step. A protein coat could be added to modified HDV RNA, possibly by using phage proteins, such as those in Armored RNA (Ambion [Europe Ltd.]) (21). This would combine the structural advantages of the HDV RNA with the advantages of the intact capsids of animal viruses.

The assay was designed so that the presence of the internal control did not detectably compromise the detection limits of the RT-PCRs (Fig. 4). When the target viruses were detected in clinical samples, the control amplicon disappeared or was reduced in intensity (Fig. 4 and 5). This may be due to the rod-like secondary structure of HDV (14, 29), which makes it a poor template for RT and which makes the resultant cDNA a suboptimal template for the first round of PCR. Subsequent rounds of PCR would be unaffected by the secondary structure, since the primers were designed from one side of the HDV rod-like genome. However, the high G+C content of HDV (60%) would adversely affect all rounds of the PCR. The difficulty of amplification of the control sequence because of its nature was illustrated experimentally by using Q solution (Qiagen Ltd.) to reduce the secondary structure of the template and the influence of its high G+C content. In the presence of Q solution, the limit of detection of the control sequence was enhanced 100-fold. Preferential amplification of the target viruses over amplification of the control was also enhanced by providing target virus primers at 0.2 μM and HDV primers at 0.1 μM and by designing target amplicons smaller than the internal control amplicon (Table 2) so that they could be more readily amplified (Fig. 5).

To date, the only conditions in which the internal control was identified to compromise the detection limit of a PCR was when it was multiplexed with highly degenerate primers specific for the target virus (data not shown). Under these conditions, in the presence of low concentrations of target virus, the control amplicon was amplified in preference to the virus amplicon. Therefore, degeneracy in the assay primers was avoided or minimized, being restricted to a single wobbling base per primer (Table 1) when it was unavoidable.

The specificities of the PCR primers were validated by using a large number of known positive clinical samples and cell culture supernatants (Table 3). The detection limit of the PCR was confirmed by using a 10-fold plasmid dilution series (Fig. 4). The difference in detection limit of the influenza A and B virus-specific RT-PCRs (in which 1 molecule was detected) compared to the RSV-, HuMV-, and PIV-specific RT-PCRs (in which 10 molecules were detected) may be due to the higher numbers of primers included in the PCRs for the last group of viruses. The lower limit of detection at the viral RNA level was not determined, as virus of known concentration is required. If a preparation of virus is assayed by cell culture, a titer can be determined, but the preparation will contain an unknown number of dead viruses; i.e., viral nucleic acid is present, but it is not possible to measure the amount.

The numbers of viruses identified in clinical samples between 29 October 2002 and 14 April 2003 (Table 5) correlated with the national trends for RSV and influenza viruses during the winter of 2002-2003 in the United Kingdom (Health Protection Agency Data[http://www.phls.co.uk/topics_az/seasonal/menu.htm]). Three coinfections were identified. This represented 0.92% of the total and is fewer than the numbers reported in many studies that have used RT-PCR (9, 12). However, the coamplification of all target amplicons from plasmids containing cloned amplicons (Fig. 5, lane +ve [positive]) indicates that coinfections can be detected. The low detection limit (as little as a single molecule of target virus) of nested RT-PCR raises the possibility that viral RNA which is not relevant to a patient's current condition may be detected. An objective measurement of the data collected in the present study, together with patient symptoms, is under way to address this issue and quantify the performances of these assays for the diagnosis of viral diseases.

The present study provides proof of concept that highly structured G+C-rich RNA or DNA molecules may be used as reaction-specific internal controls in molecular diagnostic tests. Their application to further assays based on both gel and real-time detection systems may provide a simple solution to the well-known problem of obtaining internal controls suitable for routine use.

Acknowledgments

Plasmid pTW107 was kindly supplied by John Taylor (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pa.) and Ting Ting Wu (University of California, Los Angeles). We thank Sue Wareing, Michael Alder, and Audrey Parsons for technical assistance in assessing the suitability of the assay for routine diagnostic use. We also thank Angela Brueggemann for further testing of the PIV-specific primers and for supplying cell culture supernatant of HuMV strain 26583, originally obtained from Dean Erdman at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. Alan Pawley, Nottingham Health Protection Agency Laboratory, kindly supplied 17 clinical samples previously identified as positive by cell culture; and Steve Green, Southampton General Hospital, supplied three positive clinical samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdulmawjood, A., S. Roth, and M. Bülte. 2002. Two methods for construction of internal amplification controls for the detection of Escherichia coli O157 by polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Cell. Probes 16:335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar, J. C., M. P. Pérez-Breña, M. L. Garcia, N. Cruz, D. D. Erdman, and J. E. Echevarria. 2000. Detection and identification of human parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, 3 and 4 in clinical samples of pediatric patients by multiplex reverse-transcription PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1191-1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, P. J., G. Kalpana, W. Goldberg, W. Mason, B. Werner, J. Gerin, and J. Taylor. 1986. The structure and replication of the HDV genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:8774-8778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cubero, J., J. van der Wolf, J. van Beckhoven, and M. M. López. 2002. An internal control for the diagnosis of crown gall by PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 51:387-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dingle, K. E., V. Bichko, H. Zuccola, J. Hogel, and J. Taylor. 1998. Initiation of hepatitis delta virus genome replication. J. Virol. 72:4783-4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drosten, C., E. Seifried, and W. K. Roth. 2001. Taqman 5′-nuclease human immunodeficiency virus type 1 PCR assay with phage-packaged competitive internal control for high-throughput blood donor screening. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4302-4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DuBois, D. B., C. R. Walkerpeach, M. W. Winkler, and B. L. Pasloske. 1999. Standards for PCR assays, p. 197-209. In M. Innis, D. Gelfand, and J. Sninshy (ed.), PCR applications: protocols for functional genomics. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 8.Elena, S. F., J. Dopazo, R. Flores, T. O. Diener, and A. Moya. 1991. Phylogeny of viroids, viroidlike satellite RNAs and the viroidlike domain of hepatitis δ virus RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5631-5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert, L. L., A. Dakhama, B. M. Bone, E. E. Thomas, and R. G. Hegele. 1996. Diagnosis of viral respiratory tract infections in children by using a reverse transcription-PCR panel. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:140-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayase, Y., and K. Tobita. 1997. Probable post-influenza cerebellitis. Intern. Med. 36:747-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffery, K. J., S. J. Read, T. E. Peto, R. T. Mayon-White, and C. R. Bangham. 1997. Diagnosis of viral infections of the central nervous system: clinical interpretation of PCR results. Lancet 349:313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kehl, S. C., K. J. Henrickson, W. Hua, and J. Fan. 2001. Evaluation of the hexaplex assay for detection of respiratory viruses in children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1696-1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleiboeker, S. B. 2003. Applications of competitive RNA in diagnostic RT-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2055-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kos, A., A. Dijkema, A. C. Arnberg, P. H. van der Meide, and H. Schellekens. 1986. The HDV possesses a circular RNA. Nature 323:558-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo, M. Y., J. Goldberg, L. Coates, W. Mason, J. Gerin, and J. Taylor. 1988. Molecular cloning of hepatitis delta virus RNA from an infected woodchuck liver: sequence, structure and applications. J. Virol. 62:1855-1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo, M. Y., M. Chao, and J. Taylor. 1989. Initiation of replication of the human hepatitis delta virus genome from cloned cDNA: role of the delta antigen. J. Virol. 63:1945-1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz, J., R. J. Manvell, and J. Banks. 1996. Avian influenza virus isolated from a woman with conjunctivitis. Lancet 348:901-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malorny, B., J. Hoorfar, C. Bunge, and R. Helmuth. 2003. Multicenter validation of the analytical accuracy of Salmonella PCR: toward an international standard. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:290-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munch, M., L. P. Nielsen, K. J. Handberg, and P. H. Jorgensen. 2001. Detection and subtyping (H5 and H7) of avian type A influenza virus by reverse transcription-PCR and PCR-ELISA. Arch. Virol. 146:87-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neisters, H. G. M. 2002. Clinical virology in real time. J. Clin. Virol. 25:S3-S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasloske, B. L., C. R. Walkerpeach, R. D. Obermoeller, M. Winkler, and D. B. DuBois. 1998. Armored RNA technology for production of ribonuclease-resistant RNA controls and standards. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3590-3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peret, T. C. T., G. Boivin, Y. Li, M. Couillard, C. Humphrey, D. M. E. Osterhaus, D. D. Erdman, and L. J. Anderson. 2002. Characterisation of human metapneumoviruses isolated from patients in North America. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1660-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sachadyn, P., and J. Kur. 1998. The construction and use of a PCR internal control. Mol. Cell. Probes 12:259-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selvey, S., E. W. Thompson, K. Matthaei, R. A. Lea, M. G. Irving, and L. R. Griffiths. 2001. β-Actin—an unsuitable internal control for RT-PCR. Mol. Cell. Probes 15:307-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stockton, J., J. S. Ellis, M. Saville, J. P. Clewley, and M. C. Zambon. 1998. Multiplex PCR for typing and subtyping influenza and respiratory syncytial viruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2990-2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Zee, A., C. Agterberg, M. Peeters, J. Schellekens, and F. R. Mooi. 1993. Polymerase chain reaction assay for pertussis: simultaneous detection and discrimination for Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2134-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Doornum, G. J. J., J. Guldemeester, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, and H. G. M. Neisters. 2003. Diagnosing herpesvirus infections by real-time amplification and rapid culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:576-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Elden, L. J. R., M. Nijhuis, P. Schipper, R. Schuurman, and A. M. van Loon. 2001. Simultaneous detection of influenza viruses A and B using real-time quantitative PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:196-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, K.-S., Q.-L. Choo, H. J. Weiner, R. C. Ou, R. C. Najarian, G. T. Thayer, K. J. Mullenbach, K. J. Denniston, J. L. Gerin, and M. Houghton. 1986. Structure, sequence and expression of the HDV genome. Nature 323:508-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]