Abstract

The 17-amino-acid N-terminal segment (httNT) that leads into the polyglutamine (polyQ) segment in the Huntington's disease protein huntingtin (htt) dramatically increases aggregation rates and changes the aggregation mechanism, compared to a simple polyQ peptide of similar length. With polyQ segments near or above the pathological repeat length threshold of about 37, aggregation of htt N-terminal fragments is so rapid that it is difficult to tease out mechanistic details. We describe here the use of very short polyQ repeat lengths in htt N-terminal fragments to slow this disease-associated aggregation. Although all of these peptides, in addition to httNT itself, form α-helix-rich oligomeric intermediates, only peptides with QN of eight or longer mature into amyloid-like aggregates, doing so by a slow increase in β-structure. Concentration-dependent circular dichroism and analytical ultracentrifugation suggest that the httNT sequence, with or without added glutamine residues, exists in solution as an equilibrium between disordered monomer and α-helical tetramer. Higher order, α-helix rich oligomers appear to be built up via these tetramers. However, only httNTQN peptides with N=8 or more undergo conversion into polyQ β-sheet aggregates. These final amyloid-like aggregates not only feature the expected high β-sheet content but also retain an element of solvent-exposed α-helix. The α-helix-rich oligomeric intermediates appear to be both on- and off-pathway, with some oligomers serving as the pool from within which nuclei emerge, while those that fail to undergo amyloid nucleation serve as a reservoir for release of monomers to support fibril elongation. Based on a regular pattern of multimers observed in analytical ultracentrifugation, and a concentration dependence of α-helix formation in CD spectroscopy, it is likely that these oligomers assemble via a four-helix assembly unit. PolyQ expansion in these peptides appears to enhance the rates of both oligomer formation and nucleation from within the oligomer population, by structural mechanisms that remain unclear.

Keywords: amyloid, α-helical oligomers, nucleation, polyglutamine, FTIR

Introduction

There are 91or 102 different expanded CAG repeat diseases in which a polyglutamine (polyQ) repeat expansion in a particular disease protein is associated with a neurodegenerative disorder.1 Intraneuronal polyQ-rich aggregates are found in patient brains on autopsy, and the polyQ repeat length dependence of aggregation rates in vivo3 and in vitro4,5 intriguingly mirrors the repeat length dependence of disease risk and age of onset in the diseases.1 Therefore, it has been of great interest to elucidate the mechanisms by which polyQ aggregation is initiated.

For simple polyQ sequences, aggregation rates increase with increasing repeat length,5 and the aggregation reaction follows classical nucleated growth polymerization kinetics.6–9 With such peptides, while short polyQs in the Q20 range require multimeric critical nuclei for aggregation initiation and consequently aggregate relatively slowly, polyQ sequences of Q26 or longer exhibit a critical nucleus of ~1, aggregating relatively quickly.6,9 PolyQ aggregation behavior can be further complicated by the presence of flanking amino acid sequences such as those found in disease proteins.10–17 Some flanking sequences modestly affect rates but do not fundamentally change the nucleated growth aggregation mechanism.9,13,15 Other flanking sequences, however, produce a profound change in mechanism.15,18–20

In a striking example of a flanking sequence effect, the presence of a short, 17-amino-acid N-terminal sequence (“httNT”) adjacent to the polyQ at the N-terminus of the protein huntingtin (htt) leads to an enormous rate acceleration while fundamentally changing the spontaneous aggregation mechanism.15 In this mechanism, a small portion of monomers self-associates to form roughly spherical oligomers in which all or part of the httNT segment is packed into the oligomer core, while the polyQ portion remains disordered and accessible to antibody binding.15 In a subsequent phase, the rate of aggregation of the remaining monomers dramatically increases, consistent with the operation of a nucleation event. Aggregates recovered from the reaction mixture just at the time of this rate increase exhibit evidence of a remarkable, apparently concerted transformation to more amyloid-like structure.15 The results are consistent with models in which oligomer formation contributes to polyQ amyloid formation by providing a scaffold that locally concentrates disordered polyQ segments.15,21

Many details of this mechanism, however, are yet to be elucidated. Thus, in analogy to simple polyQ peptides, aggregation rates of httNTQN peptides increase with increasing polyQ repeat length,4,15 but the mechanism of this repeat length effect on httNTQN aggregation is not well understood. Furthermore, while recent data suggest that httNT α-helix formation is part of the oligomer formation process,21 many questions remain, including the role and timing of α-helix formation, and the role(s) of the α-helical oligomers, in spontaneous amyloid assembly from httNTQN peptides. Elucidating these details is difficult with disease-associated polyQ lengths, however, since the nucleation event that triggers the rapid elongation phase likely occurs stochastically within only a small percentage of oligomers, leading to runaway elongation that obscures details of the early assembly mechanism.

We report here the results of a systematic study of httNTQNK2 peptides with short polyQ repeat lengths designed to slow the early phases of the aggregation reaction. While aggregation rates are quite slow for all of these peptides, we find some significant differences in behavior within this repeat length range. For peptides of Q7 or lower, the aggregation reaction does not progress beyond the α-helical oligomer stage. In contrast, peptides with Q8 or above are capable of moving on to the amyloid fibril stage, while nonetheless retaining an element of α-helix in the amyloid-like aggregates. Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) and circular dichroism (CD) measurements suggest that α-helix-rich oligomers build up in an organized, hierarchical fashion through tetrameric assemblies that appear to exist in equilibrium with the monomer under normal solution conditions. Other data show that oligomer dissociation rates are similar to association rates, suggesting that monomers can be generated from oligomers to support continued elongation late in the fibril growth reaction. The data shed light onto how polyQ repeat length contributes to aggregation rates in these httNTQN peptides and reveal an unprecedented case of a nucleation event associated with a net decrease in aggregation rate.

Results

Solution properties of httNTQNK2 peptides with a wide range of polyQ repeat length

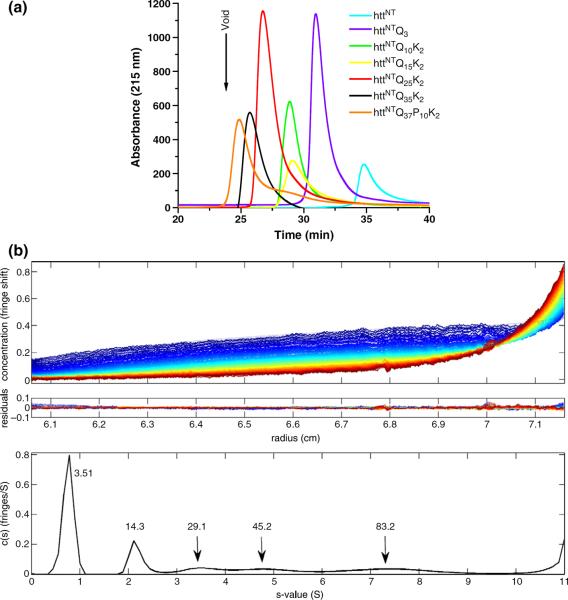

In order to address several unresolved aspects of the aggregation mechanism of htt fragments (Introduction), we purified and characterized the solution structures of a series of httNTQNK2 peptides with N ranging from 3 to 35 (Table 1). Peptides were subjected to a stringent disaggregation protocol (Materials and Methods) and were immediately subjected to analytical size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 23 °C. This analysis indicated only one detectible form, the monomer, in each case (Fig. 1a).

Table 1.

Structures of peptides used in this study

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| httNT | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF-amide |

| httNTQ | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQ |

| httNTQ3 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ |

| httNTQ4K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QKK |

| httNTQ5K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQKK |

| httNTQ6K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQKK |

| httNTQ7K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQKK |

| httNTQ8K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQQKK |

| httNTQ9K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQQQKK |

| httNTQ10K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFQQQ QQQQQQQKK |

| httNTQ15K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQKK |

| httNTQ25K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQKK |

| httNTQ35K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQKK |

| httNTQ37 P10K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQPPPPPP PPPPKK |

| K2Q37K2 | KKQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQK K |

Fig. 1.

Molecular size distribution of httNTQN peptides in PBS, pH 7.5. (a) Analytical SEC (at 23 °C) of peptides. (b) Sedimentation velocity analysis of 50 μM httNTQ10K2 at 20 °C. Data were analyzed using a continuous c(s) distribution model implemented in the program SEDFIT. The frictional ratio for each sample was a fitted parameter in the analysis, yielding 1.58 for the monomer and 1.24 for the oligomeric species. Sedimentation data, with global fits, are shown for httNTQ10K2 in the top frame, and resulting residuals for the analysis are given below the experimental data in the middle frame. The c(s) profile for the peptide species is shown in the bottom frame.

One peptide, httNTQ10K2, was further analyzed by AUC. A sedimentation velocity experiment on this peptide in PBS yielded data that fit well to a predominantly monomeric solution, with molecular weight (MW)=3500 (calculated MW=3512) (Fig. 1b). However, low levels of species with MWs of 14,300, 29,100, 45,200, and so forth, were also revealed in the best fit of the data. A shape change appears to occur upon assembly of the oligomers. The frictional coefficient decreases from 1.58 for the monomer to 1.24 for the oligomers, consistent with oligomers being more compact and/or more spherical than isolated monomers. The AUC results confirm the monomeric nature of the bulk of the sample, while at the same time suggesting that, under mild conditions, monomers can form low-MW oligomers whose sizes roughly correspond to 4-mers, 8-mers, 12-mers, and so forth, of the monomeric httNTQ10K2 peptide. We observe a similar series of small oligomers in the AUC analysis of httNT itself (data not shown), indicating that polyQ interactions are not required for formation of tetramers or higher-order oligomeric intermediates. Although we observed no corresponding oligomeric forms on injection of disaggregated peptides into SEC (Fig. 1a), these apparently fail to appear because they do not chromatograph well.

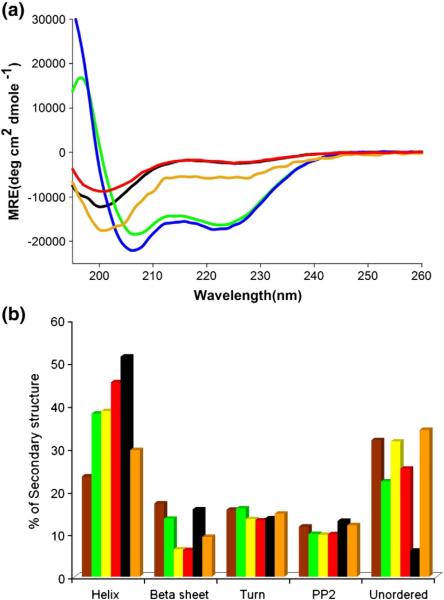

We obtained independent data consistent with an equilibrium distribution of oligomers in non-incubated samples of httNT by CD analysis. The α-helical bands in CD spectra of an httNTQ peptide exhibit a marked concentration dependence consistent with a self-associating system (Fig. 2a). The high α-helix content of samples analyzed in the 1-mM range is completely and essentially instantly reversible, since a sample diluted from a high-concentration solution exhibits a stable CD spectrum identical with that of a freshly made up solution of the same final concentration (Fig. 2a). This result has several important implications. First, it suggests that the oligomers observed in the AUC most likely exist in a rapid dynamic equilibrium with the monomer. Second, it suggests that the oligomers observed in the AUC almost certainly are α-helix rich. Third, it supports previous data15 in indicating that the httNT monomer in solution possesses no stable α-helix; rather, the bulk of the α-helix that is observed in CD analysis, at least at some concentrations, is probably due to reversible oligomer formation. Our previous CD examination of httNT peptides did not reveal such a concentration dependence,15 most likely because high concentrations in the 1-mM range were not analyzed.

Fig. 2.

CD analysis of monomeric httNTQN peptides in Tris–TFA, pH 7.4. (a) Concentration dependence of the CD spectra of httNTQ: green, 1.3 mM; blue, 0.67 mM; orange, 0.33 mM; black, 0.15 mM; red, 0.10 mM obtained by dilution from a 0.76-mM solution. All samples were analyzed in a 0.1-mm-path-length cell, except for the 0.10- mM sample, which was analyzed in a 0.1- cm cell. (b) Secondary-structure contents calculated (Materials and Methods) from CD curves, obtained in a 0.1- cm-path-length cell, of the following samples: httNTQ3, 36 μM (brown); httNTQ10K2, 32 μM (green); httNTQ15K2, 28 μM (yellow); httNTQ25K2, 25 μM (red); httNTQ35K2, 27 μM (black); httNTQ37-P10K2 20 μM (orange).

We also determined the CD spectra for each of the httNTQN peptides analyzed in Fig. 1a. Analysis of these spectra (Materials and Methods) showed only minor differences in secondary structure between the different httNT peptides, with the exception of a trend of increasing α-helix with increasing polyQ repeat length (Fig. 2b). Part of this trend may be due to contributions of α-helix from the polyQ sequence.22 It is also possible that some additional α-helix forms within the httNT segment in response to polyQ expansion. Unfortunately, CD spectroscopy is incapable of localizing secondary structure to particular sequence elements. It is clear that there are no dramatic increases in β-content as polyQ repeat length increases in this family of monomers, similar to previous results on simple polyQ peptides,5,23,24 and inconsistent with models positing large amounts of β-structure in polyQ molecules in solution.25

Aggregation properties of httNTQNK2 peptides with a wide range of polyQ repeat length

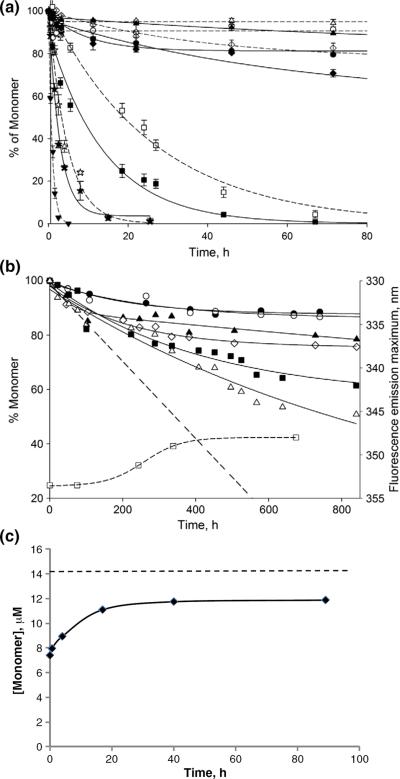

We also determined the aggregation kinetics of this set of httNTQN peptides. As reported previously,15 aggregation rates of a series of httNTQNK2 peptides are strongly dependent on polyQ repeat length (Fig. 3a). While httNTQ3 (—Δ—) aggregates very slowly, and rates increase only modestly for httNTQ10K2 (—◯—) and httNTQ15K2 (—◇—), there are substantial increases in rate as repeat lengths increase further to httNTQ25K2 (—◻—) and httNTQ35K2 (—▾—). As reported previously,15 polyQ peptides that mimic the htt exon1 fragment by containing both the httNT segment and a Pro10 segment also aggregate very much faster than simple polyQ of comparable repeat length (httNTQ37P10K2, ☆).

Fig. 3.

Aggregation kinetics of httNTQN peptides in PBS at 37 °C. (a) ~5 μM monomer with (continuous lines) and without (broken lines) 7.5 wt% httNTQ37P10K2 aggregate seeds: httNTQ3 (Δ,▲), httNTQ10K2 (◯,●), httNTQ15K2 (◊,◆), httNTQ25K2 (□,■), httNTQ35K2 (▼), and httNTQ37P10K2 (☆,★). The figure was modified from Ref.15. (b) Monomer loss (continuous lines) and shift in the Trp fluorescence emission maximum of isolated aggregates (curved broken line) for incubation of ~5 μM httNTQ4K2 (●), httNTQ5K2 (◯), httNTQ6K2 (▲), httNTQ7K2 (◊), httNTQ8K2 (■,□), and httNTQ9K2 (Δ); the straight broken line is an extrapolation of the initial oligomer formation kinetics for httNTQ9K2. (c) Dissociation kinetics of httNTQ8K2 oligomers collected after 120 h of incubation. The broken line represents total peptide (aggregate plus monomer) in the incubated sample.

Elongation rates can have an enormous influence on overall aggregation rates.8 We assessed the ability of each of these monomers to undergo seeded elongation using preformed fibrils of httNTQ37P10K2 as seeds (Fig. 3a, continuous lines). Although httNTQ3 monomers (▴) experience very little rate enhancement from seeding, monomers of httNTQ10-K2 (●), httNTQ15K2 (◆), and httNTQ25K2 (∎) all respond to the presence of seed fibrils. While these experiments are by no means definitive, the data suggest that, with the exception of httNTQ3, httNTQN monomers are all capable of undergoing seeded elongation.

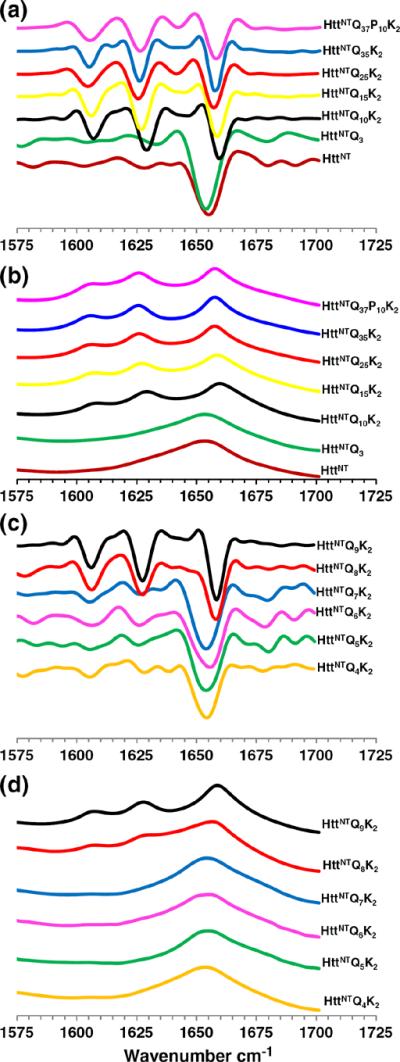

For the reactions shown in Fig. 3a, we also analyzed aggregates by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy after the reaction appeared to have reached completion. As previously described for other polyQ peptides containing an httNT flanking sequence,15 we found that aggregates of httNTQNK2 peptides with N=10 or more Gln residues exhibit three major bands in the amide I region in second-derivative (Fig. 4a) and primary (Fig. 4b) FTIR spectra: a band ~1605 cm−1, assigned to the NH2 deformation vibrations of the Gln side chain;26 a band at 1625–1630 cm−1, assigned to a β-sheet;27 and a band at 1655–1660 cm−1, assigned to C=O stretching of the Gln side chains26 (Table 2). In contrast, aggregates of the httNT and httNTQ3 peptides exhibit a single, broad band at 1655 cm−1 (Fig. 4a; Table 2). The 1648–1660 cm−1 amide I region is normally associated with α-helix.27 The β-sheet band is absent in the httNT and httNTQ3 aggregates.

Fig. 4.

FTIR spectra of isolated final aggregates. Second-derivative (a) and primary (b) spectra of final aggregates of httNT (2160 h), httNTQ3 (2160 h), httNT Q10K2 (1540 h), httNTQ15K (1080 h), httNTQ25K2 (80 h), httNTQ35K2 (24 h), and httNTQ37P10K2 (24 h). Second-derivative (c) and primary (d) spectra of final aggregates of httNTQ4K2 (1020 h), httNTQ5K2 (1140 h), httNTQ6K2 (960 h), httNTQ7K2 (1040 h), httNTQ8K2 (950 h), and httNTQ9K2 (950 h).

Table 2.

Major FTIR amide I bands of isolated httNTQN final aggregates

| Peptide | Gin N–H bending | β-Sheet | α-Helix | Gin C=O stretch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| httNT | 1654.8 | |||

| httNTQ3 | 1655.4 | |||

| httNTQ4K2 | 1604.2 | 1654.5 | ||

| httNTQ5K2 | 1604.4 | 1654.8 | ||

| httNTQ6K2 | 1606.6 | 1654.8 | ||

| httNTQ7K2 | 1606.6 | 1653.5 | ||

| httNTQ8K2 | 1606.6 | 1627.8 | 1656.7 | |

| httNTQ9K2 | 1606.3 | 1627.5 | 1658.4 | |

| httNTQ10K2 | 1606.6 | 1630.0 | 1658.9 | |

| httNTQ15K2 | 1606.8 | 1627.8 | 1658.7 | |

| httNTQ25K2 | 1604.3 | 1625.5 | 1656.3 | |

| httNTQ35K2 | 1605.0 | 1625.9 | 1659.0 | |

| httNTQ37P10K2 | 1605.2 | 1626.4 | 1658.9 |

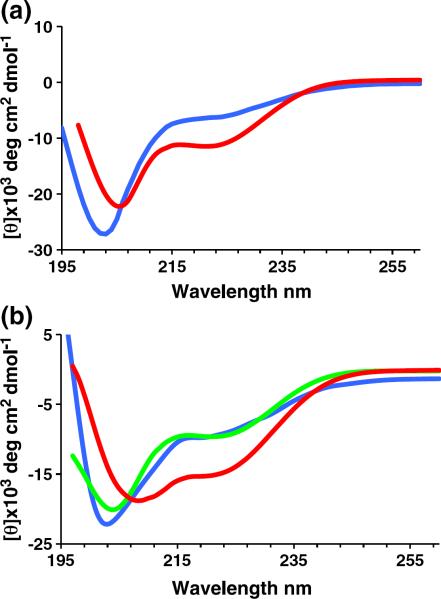

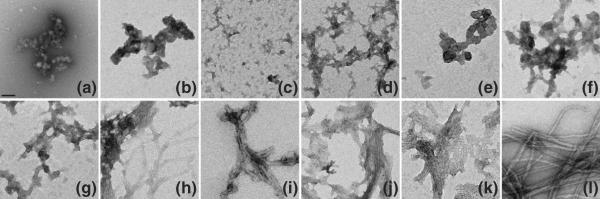

Other analyses are consistent with the above results. A CD spectrum (Fig. 5a) of partially aggregated httNTQ3 obtained after 600 h of incubation (red) exhibits an increase in α-helix content compared with the starting, freshly disaggregated peptide (blue), consistent with the FTIR data showing dominant α-helix in the isolated oligomeric aggregates. In addition, electron micrographs (EMs) of httNTQ3 aggregates exhibit clusters of oligomers (Fig. 6a), while EMs of aggregates of httNTQNK2 peptides with N=10–35 all exhibit fibrillar morphologies (Fig. 6h–k). Finally, isolated aggregates of the Q10 to Q25 peptides were all found to be good seeds for the elongation of monomeric httNTQ37P10K2 (Table 3), consistent with an amyloid-like structure in these aggregates.15,20,28 In contrast, httNTQ3 aggregates not only do not stimulate httNTQ37P10K2 aggregation compared to the unseeded reaction but also actually appear to inhibit the reaction somewhat (Table 3), similar to previously reported29 analogous results with the Aβ40 peptide. Together, these results suggest that aggregates from Q10 and higher peptides are amyloid-like, while httNTQ3 aggregates have a fundamentally different structure.

Fig. 5.

CD analysis of httNTQN aggregation. CD curves of peptides incubated in PBS at 37 °C. (a) 74 μM httNTQ3 for 0 h (blue) and 600 h (red). (b) 32.6 μM httNTQ7K2 for 0 h (blue), 48 h (green), and 120 h (red). Note that spectra reflect the mixture of monomers and aggregates at each time point.

Fig. 6.

Negative stained EMs of httNTQN peptide aggregates: httNTQ3 (a, 2160 h), httNTQ4K2 (b, 912 h), httNTQ5K2 (c, 1210 h), httNTQ6K2 (d, 800 h), httNTQ7K2 (e, 820h), httNTQ8K2 (f, 840 h), httNTQ9K2 (g, 860 h), httNT Q10K2 (h, 800 h), httNTQ15K2 (i, 1080 h), httNTQ25K2 (j, 82 h), httNTQ35K2 (k, 24 h), and httNTQ37P10K2 (l, 20 h). The scale bar represents 50 nm.

Table 3.

Seeded elongation rate constants for httNTQ37P10 monomers

| Seed aggregate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| httNTQ3 | httNTQ10 | httNTQ15 | httNTQ25 | No seed | |

| Rate constant (h−1)a | 0.085 | 0.249 | 0.236 | 0.316 | 0.171 |

Pseudo-first-order rate constants from reactions seeded with 7.5 wt% of aggregates.

Overall, this analysis of a broad range of polyQ repeat lengths suggested that there is a critical polyQ repeat length, somewhere between Q3 and Q10, at which httNTQNK2 peptides are able to grow into amyloid-like fibrils. Based on this hypothesis, we carried out a systematic examination of an additional set of peptides exploring in detail this repeat length range.

Aggregation of a narrow range of short polyQ repeat lengths in the httNTQNK2 series

We obtained and purified the polyQ repeat length series httNTQ4K2 to httNTQ9K2 and analyzed their aggregation kinetics (Fig. 3b). After about 800 h of incubation, the httNTQ4K2 (●) and httNTQ5K2 (◯) peptides reach an apparent plateau of ~12% aggregation, while the httNTQ6K2 (▴) and httNTQ7K2 (◇) peptides reach about 20% aggregation. The httNTQ8K2 (∎) and httNTQ9K2 (Δ) peptides reach substantially higher aggregation levels of 40% (httNTQ8K2) and 50% (httNTQ9K2) by 800 h.

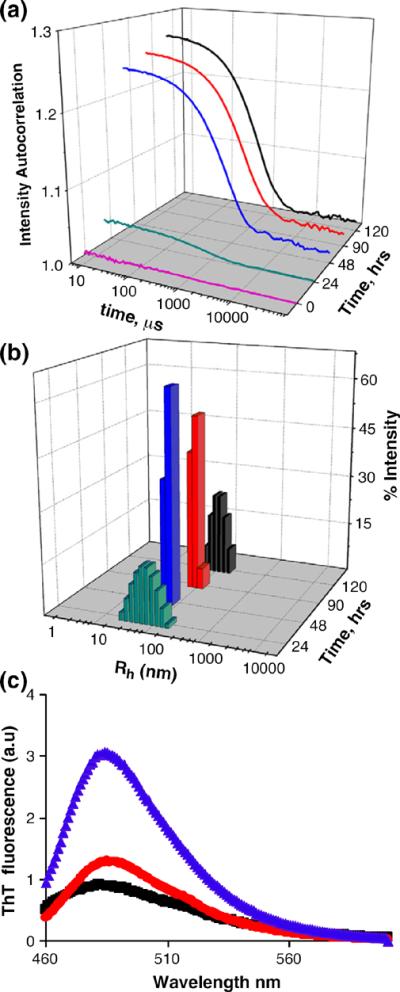

The structures of the aggregated products of these peptides exhibit a polyQ repeat length dependence that roughly correlates with the different aggregation kinetics. Second-derivative (Fig. 4c) and primary (Fig. 4d) FTIR spectra in the amide I region show a dominant α-helix band (Table 2) for the late-stage aggregates of the Q4, Q5, Q6, and Q7 peptides, in analogy to the aggregates of httNT and httNTQ3. In contrast, aggregates of the Q8 and Q9 peptides isolated at 800 h exhibit spectra essentially identical with those of all polyQ amyloid fibrils, featuring strong Gln side-chain bands and a strong β-structure band (Fig. 4c and d; Table 2). In the EM, the Q4, Q5, Q6, and Q7 (Fig. 6b–e) peptides exhibit only non-fibrillar aggregates. Although EMs of the Q8 and Q9 peptide aggregates (Fig. 6f and g) do not exhibit clear fibrillar morphologies, there is a suggestion of a filamentous substructure that may be obscured due to the greater relative mass from the non-amyloid (see below) httNT component in these peptides. A non-amyloid structure for the httNTQ7K2 aggregates is also indicated by the negligible thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescent signal from these aggregates (Fig. 7c, red curve), compared to a typical amyloid-like response from aggregates of httNTQ9K2 (Fig. 7c, blue curve). In addition, httNTQ7K2 solutions grow in α-helix content by CD over the aggregation reaction time course (Fig. 5b), and dynamic light scattering (DLS) data (Fig. 7a and b) yield a narrow range of relatively small, oligomersized particles throughout this time course.

Fig. 7.

Analysis of httNTQNK2 aggregation. Autocorrelation functions (a) and particle size distributions (b) obtained from DLS measurements of 32.6 μM httNTQ7K2 incubated in PBS at 37 °C for the times indicated. (c) Fluorescence emission spectra of ThT alone (black) or bound to final aggregates of httNTQ7K2 (red) or httNTQ9K2 (blue) at monomer-equivalent concentrations of 30 μM.

Overall, these data suggest that httNTQNK2 peptides with polyQ segments of seven or less grow into aggregates that are incapable of nucleating a β-rich amyloid structure and therefore accumulate as stable, α-helix-rich, ThT-negative aggregates. If the polyQ segment is of Q8 or longer, however, β-rich aggregates slowly develop, with overall aggregation levels increasing as polyQ repeat lengths increase.

Time course of httNTQ8K2 aggregation

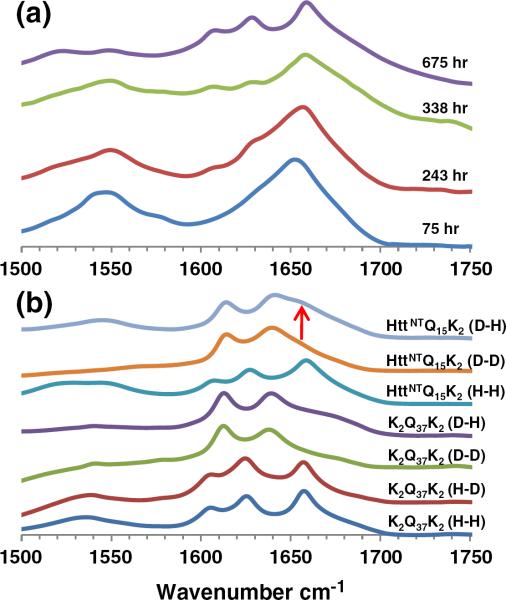

The above data define a sharp repeat length threshold in httNTQN peptides for their ability to convert from α-rich oligomers to β-rich fibrils. While suggestive, these data do not formally address whether or not those peptides that develop into β-rich aggregates do so via an α-rich oligomeric intermediate. To address this question, we isolated httNTQ8K2 aggregates at different reaction times to spectroscopically examine their secondary structures. We found that aggregates isolated at 75 h exhibit a very strong α-helix band in the FTIR at 1653 cm−1 (Fig. 8a). In addition, the fluorescence emission maximum for Trp17 in the isolated aggregates occurs at 353.5 nm (Fig. 3b, ◻), identical with that for the monomeric peptide and consistent with a Trp residue that is highly solvent exposed.15 Aggregates isolated at 243 h exhibit not only a complex FTIR spectrum with shoulders at positions of the dominant bands of mature httNTQN amyloid fibrils (Fig. 8a) but also a shift in Trp fluorescence consistent with partial burial in solvent-excluded structure (Fig. 3b). By 338 h, the growth of β-structure in the FTIR (Fig. 8a) and the shift in Trp fluorescence (Fig. 3b) are nearly complete. By 675 h, the FTIR spectrum of the httNTQ8K2 aggregates (Fig. 8a) is identical with spectra of httNTQN amyloid fibrils (Fig. 4b), and the Trp fluorescence has reached a plateau at 348 nm (Fig. 3b). These data support a model in which α-helix-rich oligomers serve as intermediates in the formation of httNTQN amyloid Interestingly, the FTIR spectra (Fig. 8a) also show that the N–H bending resonance at ~1605 cm−1 that is a common feature of all polyQ amyloid aggregates is negligible or not present in the α-helix-rich httNTQ8K2 oligomeric intermediate but develops over time, in parallel with β-sheet (in contrast to a recent description of ataxin-3 aggregation30). This suggests that this relatively sharp band is specifically associated with conformationally restricted, presumably H-bonded Gln side chains.31 This interpretation in turn supports previous data suggesting that the polyQ segments are disordered in the httNTQN oligomeric intermediates.15

Fig. 8.

FTIR structural and mechanistic analysis. (a) Primary FTIR spectra of httNTQ8K2 aggregates collected at the times indicated. (b) Primary FTIR spectra of K2Q37K and httNTQ15K2 aggregates with different exposures to H2O (“H”) and D2O (“D”). The first letter indicates the solvent used for aggregate growth, and the second letter denotes the solvent used for measurement.

The inability of polyQ httNTQN molecules with N<8 to aggregate to completion suggests that oligomer formation is reversible and is controlled by a characteristic critical concentration or Keq. To test this hypothesis, we monitored the ability of isolated httNTQ8K2 oligomers to dissociate (Materials and Methods). The results (Fig. 3c) show that oligomers in PBS at 37 °C dissociate within 20 h to an equilibrium concentration, confirming their relatively low stability and relatively rapid dissociation kinetics, on a par with their association kinetics (Fig. 3b).

Hydrogen–deuterium exchange FTIR on final aggregates

Recent solid-state NMR experiments show that the httNT segment of httNTQ30P6K2 amyloid fibrils contains a well-formed α-helical segment in residues 4–11.21 Given the strong secondary structural features observed in the FTIR spectra of the oligomeric intermediates and amyloid final products described above, one might have expected to observe an FTIR confirmation of this residual α-helical component. Unfortunately, the C=O stretch band from the Gln side chains in the final amyloid product directly overlaps the α-helix position (Table 2).

We used isotope-edited FTIR spectroscopy32 to investigate the possible existence of α-helix in the final fibril product. Figure 8b shows a typical FTIR spectrum in the amide I and II regions for an amyloid-like aggregate of a simple polyQ peptide (K2Q37K2) grown and examined in H2O (designated the “H–H” form in Fig. 8b). This spectrum exhibits the three bands for the Gln side chain and the β-sheet amide groups characteristic of all β-rich polyQ aggregates (Table 2). The assignment of these bands to the Gln side chains (1605 and 1655–1660 cm−1) and to the β-sheet (1625–1630 cm−1) was based on literature reports.26,27,30 None of these bands changes position or significant intensity when this aggregate is transferred to D2O (Fig. 8b, H–D), suggesting that the protons associated with all three of these amide resonances are strongly protected from hydrogen–deuterium exchange.

When K2Q37K2 is aggregated and analyzed in D2O, the above three bands disappear and are replaced by two new ones (Fig. 8b, D–D). [These new band locations were assigned to the β-sheet (~1612 cm−1) and to the C=O stretch from the Gln side chain (~1638 cm−1) as follows. It was previously reported that deuteration of Gln analogs has the effect of moving the C=O stretch band from around 1672 cm−1 26 to about 1640 cm−1.33 Furthermore, deuteration, as expected,32 has been observed to shift the Gln side-chain N–H band completely out of the amide I region in a Gln-containing lipopeptide.34 The amide II band at 1535 cm−1 is also expected to disappear; deuteration of proteins typically shifts the amide II bands from ~1550 cm−1 to ~1450 cm−1 .35] Reanalyzing this deuterated K2Q37K2 aggregate in H2O (Fig. 8b, D–H) produces no change, once again indicating that these FTIR bands are associated with amides that are strongly resistant to hydrogen–deuterium exchange.

A similar series of spectra of httNTQ15K2 final aggregates exhibit some subtle but important differences. The spectrum of httNTQ15K2 aggregates grown and analyzed in H2O (H–H) is remarkably similar to the corresponding H–H spectrum for K2Q37K2 (Fig. 8b). Furthermore, when httNTQ15K2 is grown in D2O and analyzed in D2O, its D–D FTIR spectrum is also essentially identical with the corresponding D–D K2Q37K2 spectrum (Fig. 8b). However, when httNTQ15K2 aggregates grown in D2O are transferred into H2O, this D–H spectrum is altered to produce two additional resonances, a band in the amide II region centered at 1545 cm−1 and a shoulder in the amide I region at ~1655 cm−1 (Fig. 8b, arrow). The emergence of these bands suggests that httNTQ15K2 aggregates possess an exchangeable, non-β-element of regular secondary structure that is not present in K2Q37K2 aggregates. Interestingly, the secondary structural feature associated with both of these band positions is the α-helix.27 The simplest explanation for this newly observed structural element is that it belongs to the httNT portion of the httNTQ15K2 peptide. This suggestion that elements of the httNT sequence reside in flexible, solvent-accessible α-helix in the amyloid fibril is consistent with recent solid-state NMR results showing the same thing.21

Discussion

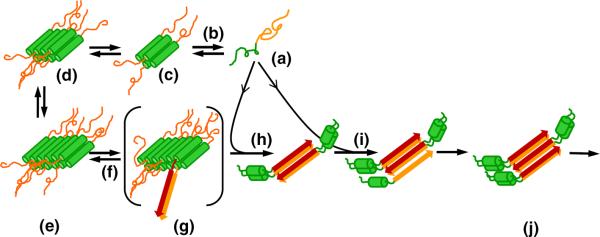

Our model for the nucleation mechanism for amyloid formation by httNTQN-type peptides suggested by these and previous experiments is shown in Fig. 9. In httNTQN monomers in solution (Fig. 9a), the polyQ portion (orange) exists in a compact coil state36–39 with no stable, regular secondary structure.5,6,23,24 The httNT segment (green) in isolation is also disordered but compact, with a modest tendency toward α-helix formation15 that is greatly enhanced in certain environments and solvents.15,40,41 Based on data presented here, it appears that the httNT segment becomes engaged in stable α-helix immediately upon assembly into oligomers and retains at least a portion of this α-helical character throughout the nucleation and elongation processes (Fig. 8a) as well as in the final httNTQN amyloid fibrils (Fig. 8b).21 Based on the high α-helix content of the oligomeric intermediates (Figs. 5 and 8), the tetrameric building block suggested by the AUC experiment (Fig. 1b), the concentration dependence of α-helix formation in a freshly solubilized httNT peptide, and the helical packing of httNT domains in crystals of some htt N-terminal fragment derivatives,41 we believe that some sort of packed four-helix assembly unit (Fig. 9c) mediates oligomer assembly.

Fig. 9.

Model for httNTQN aggregation. Disordered monomeric htt N-terminal fragments (a) (httNT, green; polyQ, orange or red) spontaneously and reversibly assemble (b) into oligomeric intermediates in which portions of httNT assemble into a bundled α-helical core (c–e), and these assemblies grow larger upon incubation. Oligomer formation results in a high local concentration of polyQ segments, increasing the frequency of formation (f) of nuclei with segments of polyQ in β-sheet structure (g). Elongation of nuclei (h) and fibrils (i) by monomer addition generates growing amyloid-like aggregates (j). As fibrils grow and monomer is depleted, oligomers that have not undergone a productive nucleation reaction dissociate (b) to provide additional monomers to support fibril elongation. According to the mechanism in this schematic, nucleation driven by enhanced local polyQ concentrations might occur within oligomers of any size. The four-helix assemblies serving as the basic units of oligomer formation in this model are depicted as being antiparallel structures, but there is no direct evidence for this.

The ability of the httNT segment to mediate a regular tetramerization of htt N-terminal fragments has not been previously recognized and may have significant implications for the cellular life of this poorly understood protein. Low MW oligomers of htt have been observed in several cell biology studies.42 Whether these multimers reflect the operation of a generalized, reversible α-helix rich oligomer formation, or are associated with specific, perhaps pathological, processes, remains to be determined.

The timing of the structural consolidation that occurs within the aggregate pool in these and previous15 studies is consistent with nucleation occurring as a structural rearrangement within the oligomer fraction (Fig. 9g). At the same time, the poor stability of oligomers relative to fibrils (Fig. 3b), as well as the ability of oligomers to relatively rapidly dissociate (Fig. 3c), suggests that most oligomers that have not undergone this rearrangement/nucleation event ultimately serve as a reservoir for releasing monomers (Fig. 9b) to support continued fibril elongation (Fig. 9i). Given that nucleation of amyloid formation for at least some polyQ repeat lengths tends to occur at a point where the reaction mixture is still ~80% monomeric15 (Fig. 3b), it is likely that the bulk of the final amyloid mass (Fig. 9j) is formed via elongation by monomer addition of a relatively small number of oligomer-derived nuclei and fibrils (Fig. 9h and i). The pivotally important role in the aggregation mechanism of the httNT segment and its ability to engage in α-helix-rich oligomer structure are further supported by experiments characterizing the abilities of httNT analogs to inhibit the oligomer-dependent aggregation pathway.43

Figure 9 shows nucleation occurring within a 12-mer, but this schematic is not meant to suggest that sporadic nucleation events are confined to a particular oligomeric species. In fact, in the short polyQ htt N-terminal fragments studied here, the aggregation kinetics suggest that significant nucleated growth of amyloid does not begin until after 200 h of incubation, at a time when about 20% of the sample consists of pelletable (i.e., much larger than 12-mer) α-helix-rich oligomers (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, it is likely that nucleation occurs within much smaller oligomers in peptides such as httNTQ35K2, where amyloid formation occurs rapidly with little, if any, apparent lag time15 (Fig. 3a).

There is an important distinction to be made between how amyloid structure is proposed to be nucleated in the model summarized in Fig. 9 and classical nucleation theory. In the classical theory, the nucleus, its oligomeric precursors, and its polymeric products, are all formed via a continuous series of discrete homologous equilibria.44 In contrast, the Fig. 9 model consists of a series of abrupt, differentiated steps: (a) tetramer formation from monomers, (b) packing of tetramers into higher oligomers, (c) nucleation within individual oligomers, and (d) elongation of nuclei into amyloid fibrils by monomer addition. Both the classical mechanism and the oligomer-mediated nucleation mechanism, however, share the central feature of a critical, energetically unfavorable step that must be traversed before strongly thermodynamically favored amyloid formation reaction can proceed. It is important to stress that the α-helix-rich oligomers are themselves not nuclei for amyloid growth. Thus, contrary to expected behavior of nuclei, α-helical oligomers (a) exhibit a finite stability allowing characterization by AUC, CD, FTIR, DLS, EM, and sedimentation; (b) do not structurally resemble the final amyloid product; and (c) are incapable of “seeding” amyloid growth.15 Instead, the nucleus is an ephemeral species (formed within the oligomer fraction) that is uniquely capable of initiating the propagation of amyloid structure. As previously pointed out,15 the model shown in Fig. 9 is similar in some respects to the “nucleated conformational conversion” model45 for initiation of yeast prion aggregation under certain conditions. Only further studies will determine whether such models will ultimately be adequate to describe other amyloid formation reactions that feature oligomeric intermediates.

Are the α-helical oligomers on- or off-pathway?

The role of non-amyloid oligomers in the amyloid assembly process has been much debated,46 with claims that oligomers are either obligate intermediates for fibril formation (on-pathway)45,47 or not required for fibril formation (off-pathway).48 The concept of intermediates being on- or off-pathway derives from the protein folding field, where the issue is whether observed intermediates are obligatory stages through which all protein molecules must pass during productive assembly, or whether their formation merely represents a shunt that must ultimately be reversed before their molecules can productively fold. Indeed, it can be very difficult to kinetically distinguish on-pathway folding intermediates from off-pathway, since both can be seen to build up and decay during the folding reaction.49,50

In analogy, in many amyloid formation reactions, including those of the htt N-terminal fragments described here, non-amyloid aggregates are formed early but are no longer evident by the end of the reaction. In the model shown in Fig. 9, the fate of some of the initial α-helical oligomers is to undergo a nucleation process to initiate amyloid growth. At the same time, a significant portion of oligomers probably do not undergo nucleation and persist only until depletion of the monomer pool, by fibril elongation, creates a thermodynamic driving force for their dissociation to monomers. This dynamic is suggested by the very slow buildup of β-structure in a persistent field of α-helical oligomers (Figs. 3b and 8) coupled with the relatively rapid dissociation of α-oligomers back to monomers (Figs. 2a and 3c). While those oligomers that play a role in nucleation are clearly on-pathway for amyloid fibril formation, the oligomers that serve only as a reservoir for monomers can be considered off-pathway, in strict analogy to the protein folding experience.51 Thus, at least for htt N-terminal fragment amyloid formation, the α-helix-rich oligomeric intermediates serve both on-pathway and off-pathway roles. It would be premature to extend these observations to all oligomeric intermediates in amyloid formation reactions, however. Many such oligomers appear to possess significant levels of β-structure, and both their roles in nucleation and their abilities to dissociate have been little investigated.

This dual role for oligomers should have different consequences in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, as monomers are depleted during elongation, those oligomers that have not undergone amyloid nucleation should tend to dissociate and disappear according to their characteristic critical concentrations. In cells continuously producing new monomers, however, this mechanism will essentially lead to a steady-state concentration of oligomers, as has been observed.42,52

Structures and role in amyloid nucleation of α-helical oligomeric intermediates

Several models exist in the literature for how httNT and polyQ might interact to provide the rapid polyQ amyloid formation kinetics observed in such molecules. Based on domain accessibility measurements of isolated oligomeric intermediates, we proposed that httNT is buried, and polyQ is disordered and solvent exposed, in oligomers, leading to a model conceptually like that shown in Fig. 9.15 A similar oligomer-mediated model was also proposed by Tam et al.,16 based primarily on photocross-linking data; this group also proposed the existence of non-covalent, long-range httNT–polyQ interactions that might enhance nucleation of amyloid growth by favoring particular polyQ conformations. Quite different models for oligomer formation and structure, in which the oligomers are held together primarily by intermolecular polyQ interactions, have been proposed based on simulations53 or experimental data.54 We think that our observation that the httNT segment alone forms oligomeric species whether or not it is connected to a polyQ chain, and that httNT by itself exhibits a concentration dependence in forming α-helix in CD measurements, argues for httNT playing a leading (rather than a following) role in oligomerization. At the same time, it remains possible that intermolecular polyQ association might play a supporting role in helping to stabilize oligomers initially brought together by httNT interactions. This hypothesis remains to be tested experimentally.

Because of this structural role, α-helix-rich oligomers also play an important functional role in greatly stimulating overall amyloid formation rates. This is illustrated by a comparison of the aggregation kinetics of molecules containing a Q25 repeat. While a 5-μM solution of httNTQ25K2 requires only ~20 h to reach 50% amyloid formation (Fig. 3a), under the same conditions, a 10-times higher concentration of K2Q25K2 reaches 50% amyloid formation only after a 10-times longer incubation time (~250 h).9 The prime importance of httNT self-association in driving amyloid formation kinetics in this system is also supported by our observations, reported elsewhere,43 of strong aggregation inhibition by httNT and various derivatives. One interesting outcome of the httNT-mediated nucleation mechanism is that the observed rate of spontaneous amyloid formation is driven by a portion of the peptide sequence that never actually engages amyloid structure.

This pivotal role of an α-helix-rich oligomeric intermediate in amyloid nucleation may not be unique to the htt system. Similar mechanisms have been suggested for other amyloid systems,55 including α-synuclein,56 amyloid β,57 islet amyloid polypeptide,58 and several model systems.59,60 The htt system, however, appears to be unique in that a substantial portion of the α-helix that is the basis of oligomer formation is actually retained in the final fibrils21 (Fig. 8b). The unusual retention of α-helix in httNT may be partly due to its intrinsic α-helical propensity, to a constitutive inability of elements of the httNT sequence to form amyloid,61 or to a fastidious discrimination by the polyQ segment against incorporating substantial portions of non-Gln sequence into the growing amyloid core. The clean compartmentalization of the htt mechanism, which can be teased apart by damping down aggregation kinetics through adjustments in polyQ repeat length, has allowed us to elucidate critical aspects of this general mechanism.

Mechanistic source of expanded polyQ acceleration of httNTQN aggregation

Previously, we observed that expanded polyQ sequences in httNTQN peptides tended to increase the efficiency with which these peptides form oligomers.15 We suggested that this trend might play a role in polyQ expansion enhancement of amyloid formation rates. We also provided FRET data consistent with the induction of a conformational expansion within the httNT segment by polyQ repeat expansion that could be the source of increased oligomer formation.15 Predictions from simulations, while differing considerably in detail, tend to support this conformational effect.53,62,63

At the same time, we believe that further studies are required to elucidate the basis of the polyQ expansion effect on oligomer formation. Data presented here indicate that polyQ expansion also contributes to the rate of amyloid formation coming out of the α-helix oligomer pool. Thus, amyloid nucleation in httNTQN peptides does not occur, even at long incubation times, unless the polyQ repeat length is at least Q8 (Figs. 3b and 4c). Furthermore, while oligomers of httNTQ8K2 populated by 100 h require another 300 h before the isolated aggregates are completely amyloid-like (Fig. 3b), fibril formation (via oligomers) from httNTQ35K2 monomers is complete after only a few hours under the same conditions (Fig. 3a). This great rate enhancement of the monomer-to-fibril transformation cannot be explained by rate effects on oligomer formation alone and must consider the nucleation and elongation events. PolyQ repeat length dependent secondary nucleation effects44,64–66 might contribute to the repeat length dependence of overall aggregation rates, but there is no indication that polyQ amyloid formation is susceptible to this process under typical growth conditions.6–9 In combination with other methodologies, reducing polyQ repeat length in order to slow aggregation rates may lead to future improvements in our understanding of the polyQ repeat length effect.

Amyloid formation by very short polyQ sequences

Our finding that httNTQN peptides as short as Q8 are capable of making amyloid is consistent with X-ray diffraction67 and mutational68 analyses, suggesting β-sheet widths of ~7 amino acids in simple polyQ amyloids. β-Sheet widths in the httNTQ8K2 peptide may be as much as 9 or 10 residues, since ssNMR of fibrils of a longer polyQ htt N-terminal fragment showed that Ser16 and Phe17 also exist in β-sheet.21 A recent analysis of the repeat length dependence of short polyQ solution conformations suggests that simple polyQ peptides in the Q8–Q12 repeat length range should not be capable of making amyloid.39 As shown herein, however, the biophysics appears to change significantly with the addition of flanking sequences that can, for example, contribute at least a few residues to the β-sheet21 and hence to its energetics.

The driving force for nucleated growth

Although nucleation events are normally associated with enhanced aggregation kinetics, the defining feature of nucleation is more accurately characterized as the overcoming of a significant kinetic barrier to a thermodynamically favorable transformation. This subtle distinction is illustrated in Fig. 3b, where it can be seen that the nucleation and elongation phases of amyloid formation by the httNTQ8K2 and httNTQ9K2 peptides exhibit kinetics that are actually slower than the preceding rates of oligomer formation (indicated by the broken line extrapolation). Nucleated growth of amyloid by these peptides occurs in spite of the slow kinetics because of the thermodynamic driving force for conversion of monomers and oligomers into amyloid.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Water (HPLC grade), acetonitrile (99.8% HPLC grade), hexafluoro-2-propanol (99.5%, spectrophotometric grade), and formic acid were from Acros Organics; trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (99.5%, Sequanal Grade) was from Pierce; and ThT was from Sigma. Chemically synthesized peptides (Table 1) were obtained from either the Keck Biotechnology Center at Yale University† or GenScript, Inc. In general, peptides were purified and subjected to rigorous disaggregation in volatile solvents (hexafluoro-2-propanol/TFA) for 16 h, followed by evaporation of solvents, resuspending the peptide film in TFA–water (pH 3) solution and ultracentrifugation at 435,680g, as previously described.9,15,69 Peptides were used immediately, without storage, after disaggregation. Most peptides contained a conservative Phe→Trp replacement at position 17 (Table 1) previously shown to have little effect on aggregation rates.15 For FTIR and ThT binding characterization and for use in seeding kinetics, aggregates were isolated from ongoing reactions and resuspended, and aggregate concentrations were determined as previously described.69

Determination of concentrations

Determination of monomer and aggregate concentrations is critical to obtaining interpretable data. We used analytical HPLC with integration of the peak from an A215 trace to quantify peptides. Although the A215 absorption is largely determined by the peptide bond, different sequences can exhibit significantly different extinction coefficients because of side-chain contributions. We calculated the expected extinction coefficient in the HPLC solvent for each sequence using a modification of the method of Kuipers and Gruppen.70 After HPLC purification of each peptide, the A215 absorbance of a portion of the pool was determined, and the concentration of the peptide was calculated from the extinction coefficient calculated from the Kuipers and Gruppen values.70 Calibrated peptide solutions were then adjusted in concentration for use as an HPLC standard, and a standard curve of peak area with respect to injected mass was generated for each peptide, allowing future determinations of mass for each peptide. These modifications of the published70 procedure compensate for observed sequence-dependent recovery efficiencies in analytical reverse-phase HPLC.

Secondary structure of the monomeric httNT peptides by CD spectroscopy

Far-UV CD measurements were performed on a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter using 0.1-cm- and 0.1-mm-path length-cuvettes. For the concentration dependence of httNTQ (Fig. 2a), lyophilized purified peptides were dissolved in pH 3 (TFA) water and centrifuged at 435,680g for 2 h; the top 50% of the supernatant was removed, adjusted to 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, and diluted with the same buffer to the desired concentrations. Spectra were collected at 1-nm resolution at a scan rate of 100 nm min−1. Four spectra were collected and averaged for each sample and corrected for the buffer blank. For measuring the conformations of monomeric httNTQN peptides (Fig. 2b), peptides were disaggregated as described in Materials, and centrifugation supernatants were adjusted to 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, and then filtered through 20-nm filters (Anotop inorganic membrane disc filter, Whatman) and immediately subjected to CD measurements. For aggregation reactions (Fig. 5), samples were prepared in PBS, pH 7.4, and filtered through the 20-nm filter, and then 400-μl aliquots of the ongoing reaction were subjected to CD measurements at 37 °C. Spectra were recorded from 195 to 260 nm at 1-nm resolution with a scan rate of 50 nm min−1. Six scans were averaged and the buffer spectrum was subtracted. For Fig. 2b, CD spectra were analyzed using the CONTINLL program from the CDPro package (lamar.colostate.edu/~sreeram/CDPro) in which the SP37A reference set (ibasis 5) was used to estimate the amount of secondary structure.71

Size-exclusion chromatography

To assess the aggregation state of peptides prior to spectroscopic analysis, we used a Superdex peptide column with a MW range of 7000 (GE Health Sciences) equilibrated in PBS on an Agilent 1200 isocratic HPLC system with a flow rate of 0.4 ml min−1. Freshly disaggregated peptide samples in TFA–water, pH 3.0, were adjusted to PBS, pH 7.4, using 10× PBS. Samples (100 μl of ~10–15 μM) were immediately injected with elution monitored at 214 nm.

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Sample preparation was tailored to insure a rigorous match to the buffer reference. Thus, freshly disaggre-gated httNTQ10K2 in pH 3 TFA–water was transported on ice to the AUC laboratory (30 min). The sample was then adjusted to PBS buffer using a 10× PBS stock and dialyzed for 2 h against PBS buffer at 23 °C. The dialysate was centrifuged 20–30 min in a refrigerated Eppendorf centrifuge (4 °C) to clear any pelletable aggregates. The recovered supernatant was used in the analytical centrifuge run, which was started approximately 30 min after the end of the centrifugation time. A reference buffer sample was prepared by following the above procedure, but with no peptide present, using a common dialysis buffer.

Sedimentation velocity experiments in a Beckman Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge were used to evaluate the distribution of species in the peptide preparations. Epon double-sector centerpieces were filled with 400 μl of samples. For all experiments, the reference buffer sample was loaded into the reference sector. Samples were centrifuged at a rotor speed of 50,000 rpm, and data were collected in fringes using interference optics. Sedimentation velocity analyses were performed with the program SEDFIT‡ (as described in detail in Ref. 72) that carry out size distribution analyses based on Lamm equation modeling.73–75 Briefly, the analysis of velocity profiles was performed by direct boundary modeling by distributions of Lamm equation solutions c(s)

| (1) |

with where a(r,t) denotes the measured absorbance or interference profiles at position r at time t, b(r) and b(t) are the characteristic systematic offsets,73 and χ1(s,F,r,t) are solutions of the Lamm equation

| (2) |

(with w denoting the rotor angular velocity, D the diffusion coefficient, and s the sedimentation coefficient) at unit loading concentration.76D and s are related via the frictional ratio F=(f/f0) and the hydrodynamic scale relationship

| (3) |

(with h and r denoting the solvent viscosity and density, respectively, and the partial specific volume of the macromolecules, calculated using the software SEDNTERP73). The partial specific volume for the htt peptides differs from that of globular proteins due to its unusual amino acid sequence composition and was determined to be 0.655 ml g−1. Initial fits to the data on httNTQ10K2 with a variety of values for in the calculated range and a single F value gave incompatible results, either with monomer MWs at expected values and oligomer MWs that were too large or monomer MWs that were unexpectedly low in fits with oligomer MWs that were expected. From these data fits, it was clear that F was different comparing the monomer and multimer. For this reason, a fit to a model that allows for a variable F value for monomer versus oligomers was employed (i.e., a model that assumes a conformational change in assembly of oligomers from monomers), taking advantage of the known MW of the monomer as the basis for assembly of the oligomers in the fitting. Satisfactory fits to the data were generated with this approach, yielding an F value of 1.58 for the monomer and an F value of 1.24 for the oligomers.

Aggregation and seeded elongation kinetics

Htt peptides were tested for their aggregation propensity and cross-seeding ability using an analytical HPLC sedimentation assay.69 Disaggregated httNTQN peptides were incubated in PBSA (PBS plus 0.05% sodium azide, w/v) at 37 °C, aliquots were periodically removed and centrifuged, and the supernatants were analyzed by analytical HPLC.

For seeded elongation kinetics, disaggregated peptides were incubated at 37 °C in PBS either alone or in the presence of the 7.5% freshly grown aggregates delivered from the stock suspension described in Materials. The rate of monomer loss over incubation period was calculated and compared with the spontaneous aggregation rate in order to estimate the seeding efficiency.

For the oligomer stability experiment, 445 μl of 620 μM freshly disaggregated httNTQ8K2 in PBSA was incubated at 37 °C for 120 h. A 300-μl aliquot was removed and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm in a tabletop centrifuge. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the pellet was suspended in 200 μl of PBSA with gentle vortexing. A 5-μl aliquot of the resulting suspension was removed and added to 30 μl of formic acid and incubated for 30 min and then analyzed by analytical HPLC to determine the total peptide concentration (monomer plus aggregates) in the sample. For the dissociation kinetics, 25-μl aliquots were removed and centrifuged 30 min at 14,000 rpm, and 5 μl of each supernatant was added to 30 μl of formic acid, and the amount of peptide in the sample was determined by analytical HPLC to yield the monomer concentration at each time point.

ThT fluorescence

Aggregates were isolated as described above and resuspended in 350 μl of PBS, to which a ThT stock solution was added to give a final ThT concentration of 40 μM. Fluorescence emission spectra were collected using a Fluorolog-3 Research Spectrofluorometer (Horiba Jobin-Yvon). Samples were excited at 445 nm and emission spectra were recorded from 460 to 600 nm. Excitation and emission slits were at 2 nm and 5 nm, respectively.

Tryptophan fluorescence measurements

Tryptophan fluorescence measurements on aggregates were conducted as previously described, using isolated aggregates resuspended in PBS.15

DLS measurements

DLS measurements were carried out on a Wyatt DynaPro light-scattering instrument. Approximately 80-μl aliquots of ongoing aggregation reactions were transferred to wells of a 386-well plate and the autocorrelation functions were measured. The correlation curves were deconvoluted using Dynamics V6 software (Wyatt Technologies Corp.) to obtain size distribution and hydrodynamic radii (Rh).

Transmission electron microscopy

Aliquots of aggregation reaction of various htt peptide samples were placed on freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and incubated for 1 min, and the excess sample was wicked away with filter paper. The sample grid was then washed with deionized water, stained with 1% uranyl acetate (w/v) solution for 3 s, and blotted. Grids were imaged using Tecnai T12 microscope (FEI Co., Hillsboro, OR) operating at 120 kV and 30,000×magnification and equipped with an ultrascan 1000 CCD camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA) with post-column magnification of 1.4×. Aggregates visualized by this protocol almost certainly are present in the sampled solutions and are not induced artifacts; previously, we showed that a solution of an htt N-terminal fragment monomer solution, added to a grid and stained by the above procedure, is free of aggregates and identical in appearance to an empty mock-stained grid.15

FTIR spectroscopy

To provide sufficient aggregates for analysis, we conducted reactions with monomers in the 0.5–1 mM range. This did not appreciably alter aggregation rates, however, presumably because of the low concentration dependence of the formation of these non-amyloid intermediates.15 Aggregates were harvested by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 45 min on a bench top centrifuge, and the pellets were washed three times with PBS to remove traces of TFA and the other solutes. Pellets containing aggregates were then resuspended in 4 μl of PBS at around 10 mg ml−1 concentration, and spectra were acquired by placing the aggregate suspension between two polished CaF2 windows using a BioCell module (BioTools, Inc.) on an ABB Bomem FTIR instrument. Data from a total of 400 scans were collected with 4 cm−1 resolution at room temperature and averaged for each sample. Residual buffer absorption was subtracted and spectral components were identified from second-derivative minima using PROTA software.

Acknowledgements

We thank Karunakar Kar for help with the DLS determination and data analysis. We also thank Dr. Sumit Goswami and Dr. Ed Wright for useful discussions and insight for the AUC analysis and Dr. Frank Ferrone for discussions on nucleation theory. EMs were collected in the Structural Biology Department's EM facility administered by Drs. James Conway and Alexander Makhov. We acknowledge funding support from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG019322).

Abbreviations used

- polyQ

polyglutamine

- htt

huntingtin

- AUC

analytical ultracentrifugation

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- MW

molecular weight

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

- EM

electron micrograph

- ThT

thioflavin T

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- PBSA

PBS plus sodium azide

Footnotes

Available online at http://www.AnalyticalUltracentrifugation.com

References

- 1.Bates GP, Benn C. The polyglutamine diseases. In: Bates GP, Harper PS, Jones L, editors. Huntington's Disease. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002. pp. 429–472. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilburn B, Rudnicki DD, Zhao J, Weitz TM, Cheng Y, Gu XF, et al. An antisense CAG repeat transcript at JPH3 locus mediates expanded polyglutamine protein toxicity in Huntington's disease-like 2 mice. Neuron. 2011;70:427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morley JF, Brignull HR, Weyers JJ, Morimoto RI. The threshold for polygluta-mine-expansion protein aggregation and cellular toxicity is dynamic and influenced by aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152161099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scherzinger E, Sittler A, Schweiger K, Heiser V, Lurz R, Hasenbank R, et al. Self-assembly of polyglutamine-containing huntingtin fragments into amyloid-like fibrils: implications for Huntington's disease pathology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4604–4609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Berthelier V, Yang W, Wetzel R. Polyglutamine aggregation behavior in vitro supports a recruitment mechanism of cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:173–182. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Ferrone F, Wetzel R. Huntington's disease age-of-onset linked to polyglutamine aggregation nucleation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11884–11889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182276099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya AM, Thakur AK, Wetzel R. Polyglutamine aggregation nucleation: thermodynamics of a highly unfavorable protein folding reaction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15400–15405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slepko N, Bhattacharyya AM, Jackson GR, Steffan JS, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Wetzel R. Normal-repeat-length polyglutamine peptides accelerate aggregation nucleation and cytotoxicity of expanded polyglutamine proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14367–14372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kar K, Jayaraman M, Sahoo B, Kodali R, Wetzel R. Critical nucleus size for disease-related polyglutamine aggregation is repeat-length dependent. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:328–336. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nozaki K, Onodera O, Takano H, Tsuji S. Amino acid sequences flanking polyglutamine stretches influence their potential for aggregate formation. NeuroReport. 2001;12:3357–3364. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dehay B, Bertolotti A. Critical role of the proline-rich region in Huntingtin for aggregation and cytotoxicity in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35608–35615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duennwald ML, Jagadish S, Muchowski PJ, Lindquist S. Flanking sequences profoundly alter polyglutamine toxicity in yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11045–11050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604547103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharyya A, Thakur AK, Chellgren VM, Thiagarajan G, Williams AD, Chellgren BW, et al. Oligoproline effects on polyglutamine conformation and aggregation. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:524–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darnell G, Orgel JP, Pahl R, Meredith SC. Flanking polyproline sequences inhibit beta-sheet structure in polyglutamine segments by inducing PPII-like helix structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;374:688–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur AK, Jayaraman M, Mishra R, Thakur M, Chellgren VM, Byeon IJ, et al. Polygluta-mine disruption of the huntingtin exon 1 N terminus triggers a complex aggregation mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:380–389. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tam S, Spiess C, Auyeung W, Joachimiak L, Chen B, Poirier MA, Frydman J. The chaperonin TRiC blocks a huntingtin sequence element that promotes the conformational switch to aggregation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1279–1285. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunders HM, Bottomley SP. Multi-domain misfolding: understanding the aggregation pathway of polyglutamine proteins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2009;22:447–451. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Chiara C, Menon RP, Dal Piaz F, Calder L, Pastore A. Polyglutamine is not all: the functional role of the AXH domain in the ataxin-1 protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;354:883–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellisdon AM, Thomas B, Bottomley SP. The two-stage pathway of ataxin-3 fibrillogenesis involves a polyglutamine-independent step. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16888–16896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ignatova Z, Thakur AK, Wetzel R, Gierasch LM. In-cell aggregation of a polyglutamine-containing chimera is a multistep process initiated by the flanking sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:36736–36743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sivanandam VN, Jayaraman M, Hoop CL, Kodali R, Wetzel R, van der Wel PC. The aggregation-enhancing huntingtin N-terminus is helical in amyloid fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4558–4566. doi: 10.1021/ja110715f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chellgren BW, Miller AF, Creamer TP. Evidence for polyproline II helical structure in short polyglutamine tracts. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;361:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masino L, Kelly G, Leonard K, Trottier Y, Pastore A. Solution structure of polyglutamine tracts in GST-polyglutamine fusion proteins. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein FA, Pastore A, Masino L, Zeder-Lutz G, Nierengarten H, Oulad-Abdelghani M, et al. Pathogenic and non-pathogenic polyglutamine tracts have similar structural properties: towards a length-dependent toxicity gradient. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang QC, Yeh TL, Leyva A, Frank LG, Miller J, Kim YE, et al. A compact beta model of huntingtin toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:8188–8196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venyaminov S, Kalnin NN. Quantitative IR spectrophotometry of peptide compounds in water (H2O) solutions. I. Spectral parameters of amino acid residue absorption bands. Biopolymers. 1990;30:1243–1257. doi: 10.1002/bip.360301309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson M, Mantsch HH. The use and misuse of FTIR spectroscopy in the determination of protein structure. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995;30:95–120. doi: 10.3109/10409239509085140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jayaraman M, Thakur AK, Kar K, Kodali R, Wetzel R. Assays for studying nucleated aggregation of polyglutamine proteins. Methods. 2011;53:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood SJ, Maleeff B, Hart T, Wetzel R. Physical, morphological and functional differences between pH 5.8 and 7.4 aggregates of the Alzheimer's peptide Ab. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;256:870–877. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natalello A, Frana AM, Relini A, Apicella A, Invernizzi G, Casari C, et al. A major role for side-chain polyglutamine hydrogen bonding in irreversible ataxin-3 aggregation. PLoS ONE. 2011:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bader R, Seeliger MA, Kelly SE, Ilag LL, Meersman F, Limones A, et al. Folding and fibril formation of the cell cycle protein Cks1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:18816–18824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arkin IT. Isotope-edited IR spectroscopy for the study of membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chirgadze YN, Fedorov OV, Trushina NP. Estimation of amino acid residue side-chain absorption in the infrared spectra of protein solutions in heavy water. Biopolymers. 1975;14:679–694. doi: 10.1002/bip.1975.360140402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Besson F, Raimbault C, Hourdou M, Buchet R. Solvent-induced conformational modifications of iturin A: an infrared and circular dichroism study of a l,d-lipopeptide of Bacillus subtilis. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 1996;52:793–803. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuart BH. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crick SL, Jayaraman M, Frieden C, Wetzel R, Pappu RV. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy shows that monomeric polyglutamine molecules form collapsed structures in aqueous solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16764–16769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608175103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Vitalis A, Wyczalkowski MA, Pappu RV. Characterizing the conformational ensemble of monomeric polyglutamine. Proteins. 2006;63:297–311. doi: 10.1002/prot.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vitalis A, Wang X, Pappu RV. Quantitative characterization of intrinsic disorder in polyglutamine: insights from analysis based on polymer theories. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1923–1937. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walters RH, Murphy RM. Examining polyglutamine peptide length: a connection between collapsed conformations and increased aggregation. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;393:978–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atwal RS, Xia J, Pinchev D, Taylor J, Epand RM, Truant R. Huntingtin has a membrane association signal that can modulate huntingtin aggregation, nuclear entry and toxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2600–2615. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim MW, Chelliah Y, Kim SW, Otwinowski Z, Bezprozvanny I. Secondary structure of Huntingtin amino-terminal region. Structure. 2009;17:1205–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ossato G, Digman MA, Aiken C, Lukacsovich T, Marsh JL, Gratton E. A two-step path to inclusion formation of huntingtin peptides revealed by number and brightness analysis. Biophys. J. 2010;98:3078–3085. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishra R, Jayaraman M, Roland BP, Landrum E, Fullam T, Kodali R, et al. Inhibiting the nucleation of amyloid structure in a huntingtin fragment by targeting α-helix-rich oligomeric intermediates. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;415:120–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrone F. Analysis of protein aggregation kinetics. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:256–274. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serio TR, Cashikar AG, Kowal AS, Sawicki GJ, Moslehi JJ, Serpell L, et al. Nucleated conformational conversion and the replication of conformational information by a prion determinant. Science. 2000;289:1317–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kodali R, Wetzel R. Polymorphism in the intermediates and products of amyloid assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mukhopadhyay S, Krishnan R, Lemke EA, Lindquist S, Deniz AA. A natively unfolded yeast prion monomer adopts an ensemble of collapsed and rapidly fluctuating structures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2649–2654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611503104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YR, Glabe CG. Distinct early folding and aggregation properties of Alzheimer amyloid-beta peptides Abeta40 and Abeta42: stable trimer or tetramer formation by Abeta42. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:24414–24422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wildegger G, Kiefhaber T. Three-state model for lysozyme folding: triangular folding mechanism with an energetically trapped intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;270:294–304. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capaldi AP, Shastry MC, Kleanthous C, Roder H, Radford SE. Ultrarapid mixing experiments reveal that Im7 folds via an on-pathway intermediate. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:68–72. doi: 10.1038/83074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powers ET, Ferrone F. Kinetic models for protein misfolding and association. In: Dobson CM, Kelly JW, Ramirez-Alvarado M, editors. Protein Misfolding Diseases: Current and Emerging Principles and Therapies. Wiley; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olshina MA, Angley LM, Ramdzan YM, Tang J, Bailey MF, Hill AF, Hatters DM. Tracking mutant huntingtin aggregation kinetics in cells reveals three major populations that include an invariant oligomer pool. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:21807–21816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williamson TE, Vitalis A, Crick SL, Pappu RV. Modulation of polyglutamine conformations and dimer formation by the N-terminus of huntingtin. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;396:1295–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Legleiter J, Mitchell E, Lotz GP, Sapp E, Ng C, DiFiglia M, et al. Mutant huntingtin fragments form oligomers in a polyglutamine length-dependent manner in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14777–14790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abedini A, Raleigh DP. A role for helical intermediates in amyloid formation by natively unfolded polypeptides? Phys. Biol. 2009;6:015005. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/6/1/015005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson VL, Ramlall TF, Rospigliosi CC, Webb WW, Eliezer D. Identification of a helical intermediate in trifluoroethanol-induced alpha-synuclein aggregation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18850–18855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012336107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirkitadze MD, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Identification and characterization of key kinetic intermediates in amyloid beta-protein fibrillo-genesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:1103–1119. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu G, Prabhakar A, Aucoin D, Simon M, Sparks S, Robbins KJ, et al. Mechanistic studies of peptide self-assembly: transient alpha-helices to stable beta-sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:18223–18232. doi: 10.1021/ja1069882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sekhar A, Udgaonkar JB. Fluoroalcohol-induced modulation of the pathway of amyloid protofibril formation by Barstar. Biochemistry. 2011;50:805–819. doi: 10.1021/bi101312h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh Y, Sharpe PC, Hoang HN, Lucke AJ, McDowall AW, Bottomley SP, Fairlie DP. Amyloid formation from an alpha-helix peptide bundle is seeded by 3(10)-helix aggregates. Chemistry. 2011;17:151–160. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.West MW, Wang W, Patterson J, Mancias JD, Beasley JR, Hecht MH. De novo amyloid proteins from designed combinatorial libraries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lakhani VV, Ding F, Dokholyan NV. Polyglutamine induced misfolding of huntingtin exon1 is modulated by the flanking sequences. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dlugosz M, Trylska J. Secondary structures of native and pathogenic huntingtin N-terminal fragments. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:11597–11608. doi: 10.1021/jp206373g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bishop MF, Ferrone FA. Kinetics of nucleation-controlled polymerization. A perturbation treatment for use with a secondary pathway. Biophys. J. 1984;46:631–644. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84062-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Padrick SB, Miranker AD. Islet amyloid: phase partitioning and secondary nucleation are central to the mechanism of fibrillogenesis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4694–4703. doi: 10.1021/bi0160462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanaka M, Collins SR, Toyama BH, Weissman JS. The physical basis of how prion conformations determine strain phenotypes. Nature. 2006;442:585–589. doi: 10.1038/nature04922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharma D, Shinchuk LM, Inouye H, Wetzel R, Kirschner DA. Polyglutamine homopolymers having 8–45 residues form slablike beta-crystal-lite assemblies. Proteins. 2005;61:398–411. doi: 10.1002/prot.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thakur A, Wetzel R. Mutational analysis of the structural organization of polyglutamine aggregates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:17014–17019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252523899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Nuallain B, Thakur AK, Williams AD, Bhattacharyya AM, Chen S, Thiagarajan G, Wetzel R. Kinetics and thermodynamics of amyloid assembly using a high-performance liquid chromatography-based sedimentation assay. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:34–74. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuipers BJ, Gruppen H. Prediction of molar extinction coefficients of proteins and peptides using UV absorption of the constituent amino acids at 214 nm to enable quantitative reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:5445–5451. doi: 10.1021/jf070337l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal. Biochem. 2000;287:252–260. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dam J, Schuck P. Calculating sedimentation coefficient distributions by direct modeling of sedimentation velocity concentration profiles. Methods Enzymol. 2004;384:185–212. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)84012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]