Abstract

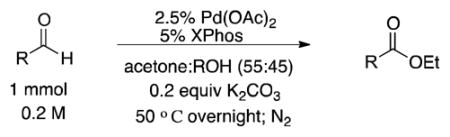

Aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes are successfully converted into their corresponding esters using Pd(OAc)2 and XPhos. This approach utilizes a hydrogen transfer protocol: concomitant reduction of acetone to isopropanol provides an inexpensive and sustainable approach that mitigates the need for other oxidants.

Historically, the most direct synthetic routes to esters either couples an activated carboxylic acid derivative with the appropriate alcohol or employs an equilibrium mediated esterification/transesterification protocol.1 These methods require stoichiometric use of toxic coupling reagents2 (e.g., DCC, HOBt), with concomitant formation of byproducts that can be difficult to remove during isolation. To address these limitations, there has been a recent emergence of investigations into direct oxidative routes to esters, allowing practitioners to select synthetic precursors in alternative oxidation states. The most widely investigated is the direct conversion of aldehydes to esters in the presence of an alcohol, and three representative approaches include: 1) oxidation of the aldehyde in the presence of an alcohol employing stoichiometric oxidants such as V2O5•H2O2,3 oxone,4 or pyridinium hydrobromide perbromide and H2O,5 2) use of NHC catalysts to activate aldehydes in situ, which in turn undergo esterification in the presence of the appropriate alcohol and stoichiometric oxidant such as MnO2,6 azobenzene,7 a substituted quinone8 or an Fe/O2 system,9 with concomitant reduction elsewhere in the molecule.10 Electrochemical oxidation has also been used in conjuction with NHC activation11 and 3) use of transition metals such as Ir,12 Rh,13 and Ru14 in the presence of an external or internal oxidant. Our group’s focus led us to explore the use of palladium catalysis to convert aldehydes directly to the corresponding esters in the presence of the appropriate alcohol, simply using acetone as the terminal oxidant.

Recent investigations have shown that palladium is a capable catalyst to effect the oxidative esterification of aldehydes, although these studies have demonstrated the requirement for stoichiometric benzyl chloride to close the Pd(II)-Pd(0) catalytic cycle.15 Under similar conditions using Pd/NHC complexes and air as the terminal oxidant, Cheng and coworkers recently demonstrated that aromatic aldehydes could be oxidatively esterified with phenols.16 Other Pd catalyzed aldehyde to ester conversions include 1,2 additions of nucleophilic siloxanes17 or arylboronic acids18 followed by oxidative esterification.

In various cross-coupling projects, our group has observed that aldehydes can be problematic substrates, providing lower-than-anticipated yields in otherwise high yielding protocols—especially when run in methanol or ethanol while using XPhos (2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,4′,6′-triisopropylbiphenyl) as a catalyst. Detailed analysis of a model reaction provided evidence of disproportionation of the aldehyde, and we observed equimolar amounts of the benzyl alcohol and ethyl/methyl benzoate derivatives. Although generally present in <5% of the overall crude reaction mixture, we hypothesized that the Pd/XPhos catalyst system might play some role in this byproduct formation.

Seeking to maximize the conversion to the ester, we hypothesized that the reduction of the aldehyde might be limited by adding a competitive “hydrogen acceptor.” Simply running the reaction with acetone as a co-solvent did just this. Preparing a reaction under strictly anaerobic conditions (glovebox, N2),19 a 0.2 M solution of 3-phenylpropanal was allowed to react with 2.5% Pd(OAc)2 and 5% XPhos in a 50:50 ethanol:acetone mixture at 50 °C overnight (Figure 1, entry b). This yielded a crude reaction mixture that was 73% ester 2, 14% alcohol 3, and 13% unreacted starting material 1. Increasing the palladium loading led to increased reactivity (5% unreacted starting material) but provided lower selectivity (18% conversion to the alcohol; Figure 1, entry a), while lowering the palladium loading saw sluggish conversion (Figure 1, entries c and d). Thus, we selected a 2.5% palladium loading and sought further optimization.

Figure 1.

Catalyst loading and substrate concentration screen. Results interpreted using HPLC analysis with biphenyl as the internal standard.

Our next step was to undertake an “additive screen”. Using High-Throughput Experimentation techniques,20 in which a screen comprised of 95 various additives at 20 mol % loading was compared to our control. Screens such as this are often quite insightful, as they illustrate both conditions that improve as well as hinder the desired outcome. To accentuate any impacts, this screen was performed at room temperature, and the reaction was quenched after only two hours. To our delight, catalytic amounts of inorganic bases (K2CO3, KHCO3, K3PO4, etc.) showed a significant positive impact on the outcome of the reaction. Under these conditions, potassium carbonate provided complete conversion of the aldehyde and formation of the desired ester in 89% assay yield, with the remainder the reduced alcohol. This additive screen also indicated that oxidants such as oxone greatly interfered with the reactivity, while V(O)(acac)2 and iodosobenzene diacetate had little impact either way. This screen gave us the first indications that the aldehyde/hemiacetal equilibrium might be important in this reaction mechanism.

The general procedure involved preparing a solution of the Pd(OAc)2 and XPhos in acetone before then adding it to the aldehyde solution in ethanol. As it aged, a color change of the palladium/ligand solution was observed. We thought this color change might be an indication that the catalyst needed to preform prior to its exposure to the aldehyde, the base, and the alcohol to maximize the desired reactivity. Indeed, without this preformation process, reaction yields were ~30% lower.

Multi-time point sampling of the reaction indicated that both the initial rate and overall conversion to the ester was dependent on the loading of the K2CO3 base (Figure 2). With a full equivalent, the reaction shows no induction period, but the desired reactivity quickly stalls, equilibrating at 72% conversion. However, employing 0.2 equivalents of K2CO3 leads to maximum conversion to the ester after a short induction period, and the reaction is complete after 30 minutes. When base is excluded, the reaction is very slow, though eventually 34% conversion to the ester is observed after 25 h. This may provide further evidence that the aldehyde-hemiacetal equilibrium is important to the catalytic cycle, or may result from the necessity to deprotonate the hemiacetal, which is required to generate the Pd-O bound intermediate required for β-hydride elimination.21 Concerning the abrupt deactivation of the catalytic system when using a full equivalent of the base, we ruled out ester to carboxylic acid degradation of the product: we used rigorously dried K2CO3 and no loss of ester or appearance of the carboxylic acid was detected by GC analysis.

Figure 2. Reaction monitoring. Monitoring the effect of various amounts of base. 0.2 equiv of K2CO3 proves ideal.

aYields determined by gas chromatography using biphenyl as an internal standard. Average of two runs agreeing to within 5%.

Next, a series of control reactions was executed to investigate mechanistic possibilities. Under an atmosphere of oxygen (balloon) and replacing acetone with THF, a 1:1 ester to alcohol ratio (disproportionation) was observed.22 Use of either Cu(OAc)223 or iron/benzoquinone24 as a co-oxidant resulted in disproportionation of the starting aldehyde. These results suggest that acetone is likely acting as a formal molecular hydrogen acceptor in the catalytic cycle. Alternative hydrogen acceptors were screened, including 2,3-butanedione and hexafluoro-acetone. Both proved to be less effective, and the low price and high reactivity combination of acetone could not be matched.

With our optimal reaction conditions in hand, a range of aliphatic alcohols was screened. When coupled with the aliphatic aldehyde, primary alcohols provided the desired product in moderate to good yield in two hours at room temperature (Table 1, entries 1a, 1b). The reaction scales well, affording a higher isolated yield while simultaneously allowing a 5-fold reduction of the Pd/XPhos loading at the 7.0 mmol scale. Sterically more demanding secondary alcohols (Table 1, entries 1c, 1e) provided the desired ester, although requiring extended reaction times at 50 °C. tert-Butanol did not engage in the oxidative esterification (entry 1d). Similarly, electronic impacts could be seen: trifluoroethanol (Table 1, 1f) was less reactive than ethanol, requiring a higher temperature and longer reaction time, yet still provided the desired ester albeit in a very modest 39% isolated yield.

Table 1.

Alcohol Scope.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | ROH | product | time(h) | yielda (%) |

| 1a | MeOH |

|

2 | 77 |

| 1b | EtOH |

|

2 | 79, 99b |

| 1c | i-PrOH |

|

8 | 60 |

| 1d | t-BuOH | no reaction | 0 | |

| 1e | s-BuOH |

|

24 | 55c |

| 1f | CF3CH2OH |

|

24 | 51c |

Isolated yields after column chromatography.

0.5% Pd(OAc)2, 1% XPhos, 24 h, 7.0 mmol scale.

50 °C

The inability to incorporate carbon-carbon double bonds within substrates proved to be a significant limitation of this method. Alkenes may serve as effective ligands for the palladium catalyst, disrupting the catalytic cycle. Thus, no oxidative esterification was observed on substrates containing carbon-carbon double bonds that were not part of aromatic systems. Further, when cinnamaldehyde was substituted for hydrocinnamaldehyde, the deep garnet color indicative of the active catalyst immediately was quenched to a pale yellow, and no formation of the desired ester was observed. Finally, the inhibition by excess base (Figure 2) may also trace its roots to the same phenomenon. Thus, we hypothesize that aldol condensation products form between acetone and the aldehyde substrates when a full equivalent of the carbonate base is used for the reaction, eventually deactivating the catalytic system in a similar manner.

Next, we screened a range of aromatic aldehydes (Table 2), and the importance of the aldehyde/hemiacetal equilibrium again was apparent, as aromatic aldehydes required extended reaction times and elevated temperatures. Reacting the aldehydes overnight at 50 °C, moderate to good yields were observed when using primary alcohols such as methanol and ethanol, but yields suffered greatly with the bulkier isopropanol. The lone exception to this was when using 4-nitrobenzaldehyde, presumably because the electron-withdrawing nature of the ring shifted the aldehyde/hemiacetal equilibrium enough to compensate somewhat for the low reactivity of the sterically more demanding isopropanol.

Table 2.

Aromatic Aldehyde Scope with Methanol, Ethanol, and Isopropanol.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yielda (%) | |

| 2a |

|

Me | 62 |

| 2b | Et | 49 | |

| 2c | iPr | 8 | |

| 3a |

|

Me | 62 |

| 3b | Et | 75 | |

| 3c | iPr | 22 | |

| 4a |

|

Me | 50 |

| 4b | Et | 47 | |

| 4c | iPr | 51 | |

| 5a |

|

Me | 52 |

| 5b | Et | 80 | |

| 5c | iPr | 17 | |

| 6a |

|

Me | 86 |

| 6b | Et | 72 | |

| 6c | iPr | 7 | |

| 7a |

|

Me | 71 |

| 7b | Et | 70 | |

| 7c | iPr | 17 | |

Isolated yields after column chromatography.

Additional aldehydes including heterocyclic motifs were converted to the corresponding ethyl esters in good to modest yields, (Table 3, 8b–11b). Unsurprisingly, the attempted conversion of 4-chlorobenzaldehyde to the corresponding ester resulted in a messy reaction from which only 5% of the desired ester could be isolated (Table 3, 15b). Competitive oxidative addition of the palladium catalyst to the aryl chloride is the likely source of the product mixture.

Table 3.

Additional Aldehyde Scope with Ethanol.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yielda (%) |

| 8b |

|

73 |

| 9b |

|

38 |

| 10b |

|

12 |

| 11b |

|

63 |

| 12b |

|

80 |

| 13b |

|

33 |

| 14b |

|

53 |

| 15b |

|

5 |

| 16b |

|

69 |

Isolated yields after column chromatography.

Finally, seeking to investigate the importance of XPhos/Pd(OAc)2 in this transformation, a range of other ligands were examined in the conversion of benzaldehyde to ethyl benzoate using our optimized conditions. Not only did XPhos prove superior to the other phosphine ligands screened, but it seems that XPhos/Pd(OAc)2 combination is crucial to effect the desired reactivity (Figure 3, L16–L19). Somewhat unexpectedly,25 the aminobiphenyl-derived Pd/XPhos precatalyst (Figure 3, footnote b) is significantly less reactive, showing poor conversion at 50 °C and providing none of the desired product at room temperature.

Figure 3. Comparison of Alternative Catalysts.a.

a Yield determined by HPLC (biphenyl internal standard).

b XPhos-Pd-G2 precatalyst:

In conclusion, a new method of direct ester synthesis from aldehydes has been developed. This approach utilizes inexpensive acetone as a hydrogen acceptor and provides a sustainable and cost-effective option to synthesize esters from the corresponding aldehydes. Initial investigations into this catalytic cycle indicate the importance of the aldehyde/hemiacetal equilibrium on the observed reactivity. The combination of XPhos with Pd(OAc)2 proved the most effective catalyst for this transformation. The results described herein also have implications for cross-coupling reactions of aldehyde-containing substrates in alcohol solvents, where the competing redox esterification may compete with the desired cross-coupling event.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support by the National Science Foundation (NSF-GOALI 0848460) and NIGMS (R01 GM035249-27, R01 GM081376) is gratefully acknowledged. Dr. Rakesh Kohli (University of Pennsylvania) is acknowledged for obtaining HRMS data.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Additional screening data, experimental procedures and characterization data for all compounds. 1H and 13C NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet athttp://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Otera J, Nishikido J. Methods, Reactions, and Applications. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2010. Esterification. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neises B, Steglich W. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1978;17:522. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopinath R, Patel BK. Org Lett. 2000;2:577. doi: 10.1021/ol990383+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Travis BR, Sivakumar M, Hollist GO, Borhan B. Org Lett. 2003;5:1031. doi: 10.1021/ol0340078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayama S, Onami T. Synlett. 2004;15:2739. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maki BE, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2008;10:4331. doi: 10.1021/ol8018488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noonan C, Baragwanath L, Connon SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:4003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar S, Grimme S, Studer A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1190. doi: 10.1021/ja910540j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy RS, Rosa JN, Veiros LF, Caddick S, Gois PMP. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:3126. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05151b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sohn SS, Bode JW. Org Lett. 2005;7:3873. doi: 10.1021/ol051269w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finney EE, Ogawa KA, Boydston AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12374. doi: 10.1021/ja304716r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Kiyooka S, Ueno M, Ishii E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:4639. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kiyooka S, Wada Y, Ueno M, Yokoyama T, Yokoyama R. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:12695. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grigg R, Mitchell T, Sutthivaiyakit S. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:4313. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murahashi S, Naota T, Ito K, Maeda Y, Taki H. J Org Chem. 1987;52:4319. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heropoulos GA, Villalonga-Barber C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:5319. [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu C, Tang S, Zheng L, Liu D, Lei A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:5662. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Zhang S, Zhang G, Chen F, Cheng J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:2480. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf C, Lerebours R. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13052. doi: 10.1021/ja063476c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin C, Wu H, Chen J, Liu M, Cheng J, Su W, Ding J. Org Lett. 2008;10:1537. doi: 10.1021/ol800176p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The reactions were initially prepared in a glovebox and the solvents were degassed to eliminate the possibility that oxygen played any role in the catalytic cycle. Reactions can be performed in air but product yields are dramatically lowered.

- 20.Dreher SD, Dormer PG, Sandrock DL, Molander GA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9257. doi: 10.1021/ja8031423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almeida MLS, Beller M, Wamg G-Z, Bäckvall J-E. Chem Eur J. 1996;2:1533. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Shue RS. Chem Commun. 1971:1510. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dams M, De Vos DE, Celen S, Jacobs PA. Agnew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:3512. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang JR, Yang CT, Liu L, Guo QX. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:5449. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Bäckvall JE, Hopkins RB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:2885. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bäckvall JE, Hopkins RB, Grennberg MM, Awasthi AK. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5160. [Google Scholar]; (c) Piera J, Bäckvall JE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:3506. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinzel T, Zhang Y, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14073. doi: 10.1021/ja1073799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.