Abstract

Background

Despite excellent breastfeeding initiation rates, physician mothers as a group are at risk of premature breastfeeding cessation. The main obstacles and reasons for breastfeeding cessation among physician mothers are work-related. We conducted this study to further explore physician mothers' personal infant feeding decisions and behavior as well as their clinical breastfeeding advocacy.

Subjects and Methods

We interviewed 80 physician mothers, mainly affiliated with the University of Florida College of Medicine (Gainesville, FL), using a questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were calculated with SPSS software version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

The 80 mothers had a total of 152 children and were able to successfully initiate breastfeeding for 97% of the infants. Although maternal goal for duration of breastfeeding had been 12 months or more for 57% of the infants, only 34% of the children were actually still breastfeeding at 12 months. In 43% of cases, physician mothers stated that breastfeeding cessation was due to demands of work. Furthermore, physician mothers who reported actively promoting breastfeeding among their female patients and housestaff had significantly longer personal breastfeeding duration compared with physician mothers who denied actively promoting breastfeeding.

Conclusions

Our findings not only emphasize the discrepancy between physician mothers' breastfeeding duration goal and their actual breastfeeding duration, but also highlight the association between their personal breastfeeding success and their own active breastfeeding advocacy. Whether this association is causal cannot be determined by the current study and can be examined further by prospective studies. Our results support developing and implementing workplace strategies and programs to promote breastfeeding duration among physician mothers returning to work.

Background

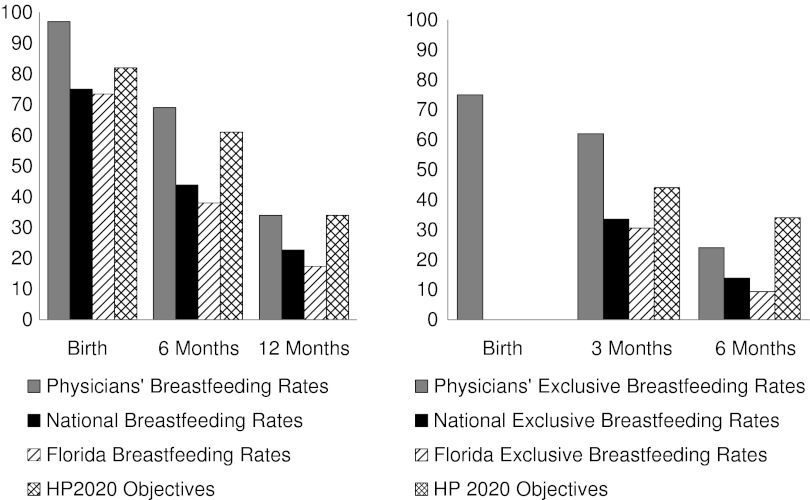

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently released the Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) objectives. HP2020 contains aims to increase breastfeeding rates in the United States to 82% ever-breastfed, 61% at 6 months, and 34% at 1 year.1 Currently, 75% of infants born in the United States are initially breastfed, but rates fall to 44% at 6 months and 24% by 12 months.2 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life,3 and HP2020 exclusive breastfeeding goals are set for 46% at 3 months and 26% at 6 months.1 However, only 15% of babies in the United States are exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months.2 We need to continue to identify and implement effective interventions to improve breastfeeding behavior and achieve HP2020 objectives.

One of the interventions that effectively increases breastfeeding initiation and continuation of mothers is their physicians' breastfeeding advice.4–7 It is interesting that the strongest predictor of physicians' clinical breastfeeding advocacy is their personal or spousal breastfeeding behavior.8–11 Therefore, physician mothers' breastfeeding behavior impacts not only the well-being of themselves and their families, but eventually the health of their patients and patients' families. Despite excellent breastfeeding initiation rates, physician mothers as a group are at risk of premature breastfeeding cessation.12–16 Physician mothers who attempt to maintain breastfeeding after maternity leave identify two main obstacles at work: lack of sufficient time and adequate place for milk expression.12–14 Similarly, physician mothers' main reasons for breastfeeding cessation, especially between 1 and 12 months postpartum, are work-related.12–14,17

Our recent pilot study of 50 physician mothers, conducted in Baltimore, MD, demonstrated discrepancy between their breastfeeding intention and behavior, suggesting that work-related factors not only influence physician mothers' breastfeeding duration, but also might have a larger impact than their education and intentions.17 To expand on these findings, we decided to replicate a similar study at the University of Florida College of Medicine (Gainesville, FL). This study expands on prior research and its purpose is to determine the relationship between an individual physician's personal breastfeeding behavior and her breastfeeding advocacy.

Subjects and Methods

Survey instrument development

The questionnaire used in our previous study was modified to include assessment of breastfeeding advocacy by the participants. The development of that questionnaire has been previously described.17 The final instrument contained 53 items and took approximately 20–30 minutes to complete. Questions included demographic information and previous breastfeeding education. Participants were asked a series of questions for each of their children, including current age, whether or not the infant was ever breastfed, and age at which the infant first received anything other than breastmilk.

A new “yes/no” question was added to assess if breastfeeding was discontinued “due to demands at work.” Another “yes/no” question was developed to inquire whether a participant reported actively promoting breastfeeding among their female patients. For the purposes of this study and this article, we have defined this as clinical breastfeeding advocacy. Workplace breastfeeding advocacy was defined as the participant's active promotion of breastfeeding among their female housestaff. To assess workplace breastfeeding advocacy, all participants were asked about active breastfeeding promotion among female housestaff. Participants who reported not actively promoting breastfeeding among patients or housestaff were then asked the reason(s) for not doing so. While they were given a choice of possible reasons for not actively advocating breastfeeding, such as lack of time or expertise, they also had the option of choosing “other” and explaining their reasons.

Recruitment

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida approved this study protocol. Physicians (faculty and housestaff) of all disciplines at the University of Florida were notified of the study by e-mail messages distributed by residency and fellowship program directors at the institution as well as the institution's listserv for housestaff and faculty. The recruitment e-mails contained information about the nature of the study as well as e-mail and phone number of the Principal Investigator (PI) (M.S.). The PI set up interviews with potential study participants as they responded to express interest in the study.

Study

Criteria for participation included being a female physician and having had at least one biological child. Physicians were included whether they were in training (e.g., resident or fellow) or had completed training (e.g., faculty at academic site or community practice). Participants were included, regardless of their infant feeding methods. Initially, recruitment efforts only focused on physicians affiliated with the University of Florida College of Medicine. However, when physicians not affiliated with the institution at the time of the study volunteered to participate, we included them as long as they were otherwise eligible and could be interviewed in person. All interviews were conducted in person by the PI between October 2009 and July 2011.

Analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools18 hosted at the University of Florida. Descriptive statistics were calculated with SPSS software version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). We used the infant as the unit of analysis for calculation of rates because breastfeeding practices of some multiparous mothers varied with different offspring. All comparisons were performed at a 95% confidence level.

Results

Characteristics of mothers and children in the study

Eighty interviews were completed in person with physicians. The participants' ages ranged from 26 to 60 years at the time of the study, with a mean age of 38 years. Twenty-five (31%) were still in training, and 55 (69%) had completed training. Additional demographics are summarized in Table 1. Seventy-eight participants (97.5%) worked at the University of Florida or affiliated institutions, and two (2.5%) learned about the study through their spouses who were affiliated with the institution. Participants' specialties are described in Table 2. Only 30% (n=24) of physicians in the survey reported receiving breastfeeding education during residency, and fewer still (20%; n=16) reported this in medical school. Although the average length of maternity leave was 9.5 weeks (SD, 8.6 weeks), the average duration of paid leave was 6.7 weeks (SD, 6.9 weeks).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Physician Mothers in the Study (n=80)

| Demographic | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 26–30 | 12 | 15 |

| 31–34 | 15 | 19 |

| 35–39 | 27 | 34 |

| 40–49 | 20 | 25 |

| 50–60 | 6 | 8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 76 | 95 |

| Not married | 4 | 5 |

| Training level | ||

| Post-training | 55 | 69 |

| In-training | 25 | 31 |

| Number of children | ||

| 1 | 27 | 33.75 |

| 2 | 38 | 47.50 |

| 3 | 11 | 13.75 |

| 4 | 4 | 5.00 |

Table 2.

Specialty Distribution of Physician Mothers in the Study (n=80)

| |

Study participants |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | Number | Percentage (%) | Actual numbersa |

| Anesthesiology | 5 | 6 | 47 |

| Dermatology | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Family Medicine | 4 | 5 | 41 |

| General Surgery and surgical subspecialties | 5 | 6 | 40 |

| Internal Medicine and medicine subspecialties | 37 | 46 | 140 |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 4 | 5 | 22 |

| Pathology | 2 | 3 | 31 |

| Pediatrics and pediatric subspecialties | 14 | 18 | 110 |

| Psychiatry | 3 | 4 | 43 |

| Radiology | 4 | 5 | 21 |

| Radiation oncology | 1 | 1 | 11 |

The last column represents the total numbers of female faculty and housestaff affiliated with each department in 2012 at the University of Florida College of Medicine. We do not have accurate data or markers for how many might be parents or have children.

The 80 physicians included in the study had a total of 152 children, ranging in age from 6 weeks to 28 years old. Four of the children (3%) were born prior to the mother entering medical school, seven (5%) during the mother's medical school years, 44 (29%) during residency, 23 (15%) during fellowship, and 66 (43%) after maternal completion of medical training (Table 3). Eight children (5%) were born in other stages of maternal career (three after the mother had completed medical school and before starting training, one in the interval between the mother's different stages of postgraduate training, and four after maternal completion of postgraduate training but while the mother was unemployed).

Table 3.

Maternal Factors (Work Site and Personal) Associated with 152 Pregnancies

| Factor | Ratio (n/total n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Work environment during pregnancy | ||

| Very unsupportive | 10/152 | 7 |

| Somewhat unsupportive | 11/152 | 7 |

| Neutral | 15/152 | 10 |

| Somewhat supportive | 49/152 | 32 |

| Very supportive | 66/152 | 43 |

| Not applicable | 1/152 | 1 |

| Stage of maternal career at childbirth | ||

| Prior to medical school | 4/152 | 3 |

| During medical school | 7/152 | 5 |

| During residency | 44/152 | 29 |

| During fellowship | 23/152 | 15 |

| While attending | 66/152 | 43 |

| Other | 8/152 | 5 |

| Maternal work status postpartum | ||

| Full-time | 122/152 | 80 |

| Part-time | 29/152 | 19 |

| Had not returned by time of study | 1/152 | 1 |

| Flexibility of work schedule/rotation postpartum | ||

| Yes | 62/151a | 41 |

| Somewhat | 25/151a | 17 |

| No | 64/151a | 42 |

| Maternal mental health postpartum | ||

| Severely depressed | 8/152 | 5 |

| Mildly depressed | 27/152 | 18 |

| Not depressed at all | 117/152 | 77 |

| Maternal energy level postpartum | ||

| Always tired | 15/152 | 10 |

| Often tired | 58/152 | 38 |

| Sometimes tired | 68/152 | 45 |

| Seldom tired | 11/152 | 7 |

| Maternal stress level postpartum | ||

| Very stressed | 40/152 | 26 |

| Somewhat stressed | 64/152 | 42 |

| Seldom stressed | 48/152 | 32 |

| Sufficient time at work for milk expression | ||

| Never | 8/122b | 7 |

| Occasionally | 15/122b | 12 |

| Sometimes | 33/122b | 27 |

| Often | 35/122b | 29 |

| Always | 31/122b | 25 |

| Appropriate place at work for milk expression | ||

| Never | 12/122b | 10 |

| Occasionally | 18/122b | 15 |

| Sometimes | 18/122b | 15 |

| Often | 9/122b | 7 |

| Always | 65/122b | 53 |

The total number used for determining ratio and percentages of schedule flexibility postpartum was 151, as one mother had not returned to work yet.

The total number used for determining ratio and percentages of availability of time and place at work for milk expression was 122, the number of situations where mothers expressed milk at work postpartum.

Breastfeeding intentions and behavior

Intention to breastfeed was 100% as all 80 mothers reported planning to breastfeed during all pregnancies. The two most frequent reasons cited by study participants for their intention to breastfeed were infant health (98%) and bonding (84%). Other reasons reported for maternal intention to breastfeed include maternal health, convenience and cost compared with formula, support and recommendations from friends and family (including spouse and mother), and healthcare recommendations (pediatricians, obstetricians, official guidelines, and lactation consultants), breastfeeding class, wanting to be a role model to patients, and the desire to contribute to the baby's well-being while working. In 16 pregnancies, mothers either reported not having a goal regarding the length of breastfeeding or stated that they had hoped to breastfeed until return to work or as long as possible. In 136 (89%) pregnancies, mothers expressed numerical goals for breastfeeding duration that ranged anywhere from 1 to 24 months. In 57% of cases, mothers planned to breastfeed for at least 12 months.

Of the 152 children, 114 were exclusively breastfed at birth (75%), 33 received a combination of breastmilk and formula (22%), and five children received formula only (3%). Mothers successfully transitioned 20 of the 33 infants who started life with both breastmilk and formula to only breastmilk in the first few weeks postpartum (13%). Using the infant as the unit of analysis, breastfeeding initiation rate was 97% (147/152), and continuation rates were 69% (105/152) at 6 months and 34% (52/152) at 12 months (Fig. 1). The mean duration of breastfeeding was 9.3 months (SD, 6.3 months; range, 0–30 months). The mean duration of exclusive breastfeeding was 3.6 months (SD, 2.5; range, 0–13 months). Overall, 75% of infants were exclusively breastfed at birth, 62% at 3 months, and 24% at 6 months of age (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

(Left) Overall and (Right) exclusive breastfeeding rates of physician mothers in our study compared with respective national rates in the United States and Florida, obtained from National Immunization Survey data for 20082 and Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) objectives.1

Mothers reported that they were unable to provide any breastmilk for five of the infants. Three infants did not receive breastmilk because of maternal health reasons and one because of reported lack of breastmilk, and one mother decided “not to even try breastfeeding” because of previous stressful breastfeeding experiences with her other two children. The two most frequent reasons reported for complete breastfeeding cessation before 12 months were inadequate milk supply (n=49) and lack of sufficient time at work for milk expression (n=24). In 43% of cases, physician mothers stated that breastfeeding cessation was due to demands of work. In 132 instances, mothers continued breastfeeding after return to employment, and in 122 of these cases, mothers reported expressing milk at work. The median breastfeeding duration of infants breastfed during training was 8.9 months, compared with 9.6 months for infants breastfed after completion of training (p=0.540). The mothers' goal for duration of breastfeeding had a statistically significant association with their actual breastfeeding duration (r=0.652, p<0.0001). Eighteen children were still breastfeeding at the time of study. Of the children who were no longer receiving breastmilk, 46 had been weaned within 3 years of the study.

Breastfeeding promotion and advocacy

Workplace breastfeeding advocacy was assessed by asking participants whether they actively promoted breastfeeding among female housestaff. We considered physicians to have workplace breastfeeding advocacy if they answered yes or provided examples of their advocacy. Physicians who reported advocating breastfeeding among housestaff had statistically significantly longer personal breastfeeding duration and exclusive breastfeeding duration compared with physicians who reported not advocating breastfeeding among housestaff (Table 4).

Table 4.

Duration of Personal Breastfeeding and Breastfeeding Advocacy

| |

Duration (in months) of |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Breastfeeding |

Exclusive breastfeeding |

||

| Breastfeeding promotion | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Clinical | ||||

| Yes | 10.00 | 6.34 | 3.70 | 2.49 |

| No | 5.98 | 4.29 | 2.80 | 2.34 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.069 | ||

| Workplace | ||||

| Yes | 10.05 | 6.26 | 3.77 | 2.45 |

| No | 3.11 | 2.31 | 1.66 | 1.90 |

| p value | 0.000 | 0.002 | ||

Clinical breastfeeding advocacy was assessed by asking about breastfeeding promotion among patients. We considered physicians to have active clinical breastfeeding advocacy if they answered yes or provided examples of breastfeeding advocacy among patients. Nine physician mothers reported that they did not have breastfeeding patients and were eliminated from this part of the analysis (Table 4). Physicians who reported clinical breastfeeding advocacy had, on average, breastfed 4 months longer than the physicians who reported not actively promoting breastfeeding among their patients (by t test p<0.001). The main reasons for not wanting to advocate breastfeeding among patients and housestaff were avoidance of “being judgmental, putting pressure on other mothers, or making mothers feel guilty.” Many of these physician mothers identified feeling pressure, guilt, or being judged when they had to start supplementation with formula or to completely give up on their breastfeeding efforts.

Breastfeeding advocacy was also associated with maternal specialty (by Fisher's exact test p=0.0154). Pediatricians, obstetricians, and family practitioners consistently reported active breastfeeding promotion. It is interesting that even mothers in less obvious specialties, such as internal medicine, anesthesiology, psychiatry, and general surgery, reported actively promoting breastfeeding. For example, multiple internal medicine physicians reported discussing infant feeding choices prior to pregnancy, in early pregnancy (before referral to obstetricians), and postpartum, after female patients are released from their obstetricians. Anesthesiologists who reported active promotion considered pharmacotherapy choices in their lactating patients and also educated them about “pumping and dumping,” if necessary. A female general surgeon reported providing breast pumps for lactating patients admitted to her service. Psychiatrists reported discussing safety of psychotropic agents with their lactating patients.

Using Fisher's test or χ2 tests, we found that maternal goal for breastfeeding duration was also significantly associated with clinical (p<0.001) and workplace (p<0.001) breastfeeding advocacy. Mothers who reported that their breastfeeding cessation was work-related were significantly less likely to report workplace breastfeeding advocacy (p=0.001), but not clinical breastfeeding advocacy (p=0.458). Mothers who did not continue breastfeeding after return to work were significantly less likely to report clinical (p=0.031) and workplace (p<0.001) breastfeeding advocacy. We did not find an association between physicians' clinical and workplace breastfeeding advocacy and maternal age, marital status, breastfeeding education (medical school or residency), partner work status, perceived level of support at work environment during pregnancy, length of maternity leave, duration of paid leave, maternity leave type, work schedule flexibility, infant feeding method at birth, maternal mental health postpartum, maternal energy level postpartum, maternal stress level postpartum, satisfaction with personal breastfeeding duration, availability of time or place at work for milk expression, and workplace support for breastfeeding efforts.

Qualitative data

The one-on-one interaction with the survey participants allowed for collection of descriptive and qualitative data, even in response to forced response items in the questionnaire. For example, physicians in surgical-based fields universally reported less perceived support of their breastfeeding efforts at work as well as more employment-related obstacles. One faculty physician expressed her opinion that it would be impossible for anesthesiology housestaff to continue breastfeeding after return to work because of logistics of patient flow and availability of coverage for operating rooms.

The one-to-one interaction also revealed lingering ambivalence about childbearing and breastfeeding during training. For example, one faculty member reported being supportive of breastfeeding among both patients and housestaff, but also stated that she delayed having children during training because “it would not be fair to put fellow housestaff through her pregnancy and childbirth.” Another consistent theme discussed by this study's participants was lack of formal maternity leave. With the exception of the handful of participants who had experienced childbirth while employed in New York or California, most mothers in this study reported using sick leave, vacation time, unpaid leave, or a combination thereof as their maternity leave. Physician mothers also volunteered information about lack of accommodations for breastfeeding mothers when taking medical boards for different specialties.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that 97% of infants of physician mothers in this study were breastfed at birth, and although maternal intent to breastfeed for at least 12 months was 57%, only 34% of infants continued to receive breastmilk at 12 months of age. Furthermore, 43% of cases of breastfeeding cessation were reported to be due to work-related demands. These results support the findings from our earlier pilot at a different site that “work-related factors not only influence physician mothers' breastfeeding behavior, but might have a larger impact than these mothers' education and intentions on their breastfeeding duration.”17 Similar to physician mothers interviewed in Baltimore, the majority of physician mothers interviewed in Gainesville, reported intent to breastfeed as well as awareness of benefits of breastfeeding and current infant feeding guidelines. Although their intentions and knowledge correlated with their breastfeeding initiation practices, their breastfeeding maintenance was then determined by interaction of personal factors, such as intent and knowledge, with work-related ones. Improving breastfeeding duration of physician mothers requires identification of other work-related modifiers and recognition of importance of institutional factors, such as support for time to breastfeed or express milk at work and a place to do so.

Perhaps an even more important finding was the positive association between physicians' personal breastfeeding duration and their self-reported clinical breastfeeding advocacy. Frank and co-workers have reported a similar association between physicians' other healthy personal habits and their preventive counseling practices.19–21 In 1995, Freed et al.11 found that among a large national sample of physicians in training and practice, previous personal or spousal breastfeeding experience was the greatest predictor of physician self-confidence in effective breastfeeding counseling. Our data expand on the results of Freed et al.11 and suggest that there might also be an association between the quality of a physician mother's breastfeeding experience and her breastfeeding advocacy.

These findings can be interpreted in several ways. A physician mother's overall breastfeeding advocacy might impact her own breastfeeding duration. On the other hand, a physician mother's breastfeeding success might strengthen her breastfeeding advocacy. Alternatively, the association between breastfeeding duration and advocacy might actually reflect the impact of these mothers' original goals on their subsequent breastfeeding behavior as well as advocacy, rather than any direct link between duration and advocacy. Another possibility is that there might be other factor(s), unidentified by our study, that independently affect maternal breastfeeding goals, actual breastfeeding duration, and the likelihood of becoming a strong advocate for breastfeeding among both patients and housestaff.

Our cross-sectional study cannot determine causality. However, if the association between physicians' personal breastfeeding experience and breastfeeding advocacy is causative, then interventions focused on promoting breastfeeding among physicians and enabling them to breastfeed successfully after return to work can potentially improve their attitudes toward advocating breastfeeding among their patients and society. It is noteworthy that we did not find an association between either clinical or workplace breastfeeding advocacy and any of the presumptively negative workplace environmental factors that we might suspect would have interfered with physicians' breastfeeding. However, we believe that this study did not have statistical power to find such an association and that a larger prospective study would better assess not only causality, but also the relationship between physicians' workplace factors and their breastfeeding advocacy.

It is important for us to mention other study limitations. Although insufficient numbers of mothers in each medical specialty and each stage of career subset made statistically meaningful comparisons impossible, to our knowledge this study is the second largest published multispecialty physician breastfeeding study in the United States. Because we gathered some retrospective data of previous breastfeeding behavior, there is a potential for recall bias. Although the validity and reliability of maternal recall for breastfeeding intent are not clear, previous studies have established that maternal recall is a valid and reliable estimate of breastfeeding initiation and duration, especially when the duration of breastfeeding is recalled within 3 years.22,23 More than one-third of the data (64 of 152 children) in this study represent data collected within 3 years of breastfeeding practice. Another possible limitation of this study is self-selection bias as we relied on data provided by physician mothers who volunteered to participate in the study. Although such bias would not affect the internal validity of our results, it might affect the external validity and generalizability of our finding. If the wording of the recruitment e-mail discouraged mothers who did not intend to or were unable to breastfeed or if these mothers were less likely to respond because of various reasons, including lack of interest in the topic or guilt, breastfeeding rates reported in this study might overrepresent actual breastfeeding rates among physician mothers. As such, even though we found that all mothers in this study intended and tried to breastfeed their infants, we cannot claim that all physician mothers in the United States intend and attempt to breastfeed all of their children. Similarly, although our study population met or exceeded most of the HP2020 goals (with the exception of breastfeeding at 12 months and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months), we cannot conclude that our results represent breastfeeding behavior of all physician mothers in the United States (Fig. 1). As a mainly single-center study at an academic medical center, a further potential limitation is institutional bias, including the perceived “pro-breastfeeding stance” of the academic institution. Although the single-institution aspect limits the generalizability of our findings, it also allowed for detailed, in-depth analysis with extensive one-on-one interviews.

The descriptive data we gathered have important implications for future research, involving a larger and more diverse sample from various healthcare settings to determine whether significant differences exist in infant feeding behavior and breastfeeding advocacy of physician mothers in different healthcare settings, specialties, and those in training versus physician mothers in practice. The results of such a study, with a larger sample size of physicians from different institutions, would also be more generalizable. Cause-and-effect relationships between personal infant feeding behavior of physician mothers and their breastfeeding advocacy would best be assessed prospectively. Another area to further explore would be the relationship of physicians' self-perceived clinical breastfeeding advocacy and their patients' perception of effectiveness of the advocacy as well the patients' actual breastfeeding behavior.

Conclusions

Ultimately our findings not only support the importance of work-related factors in breastfeeding maintenance among physician mothers, but also highlight the association between physicians' personal breastfeeding success and their clinical breastfeeding advocacy. Whether this association is causal cannot be determined by the current study and should be examined further by prospective studies. Our results support developing and implementing workplace strategies and programs to promote breastfeeding duration among physician mothers returning to work. Formal maternity leave policies, nonclinical duties when physician mothers first return to work, designated private space for breastfeeding or expressing milk, protected time for milk expression during work, sanitary storage for expressed breastmilk, onsite or near-site child care, and work site support are modifiable factors that might influence physician mothers' breastfeeding duration after return to work.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Clinical and Translational Science Institute, National Institutes of Health grant 1UL1RR029890.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020/Objectives.htm. [Nov 9;2011 ]. www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020/Objectives.htm [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Among U.S. Children Born 2000–2008, CDC National Immunization Survey. www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.htm. [Mar 10;2012 ]. www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.htm

- 3.Heinig MJ. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations on breastfeeding and the use of human milk. J Hum Lact. 1998;14:2–3. doi: 10.1177/089033449801400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taveras EM. Li R. Grummer-Strawn L, et al. Opinions and practices of clinicians associated with continuation of exclusive breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e283–e290. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.e283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sikoski J. Renfrew MJ. Pindoria S, et al. Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD001141. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer MS. Chalmers B. Hodnett ED, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): A randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285:413–420. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labarere J. Gelbert-Baudino N. Aryal AS, et al. Efficacy of breastfeeding support provided by trained clinicians during an early, routine, preventive visit: A prospective, randomized, open trial of 226 mother-infant pairs. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e139–e146. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freed GL. Clark SJ. Cefalo RC, et al. Breast-feeding education of obstetrics-gynecology residents and practitioners. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1607–1613. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freed GL. Clark SJ. Lohr JA, et al. Pediatrician involvement in breast-feeding promotion: A national study of residents and practitioners. Pediatrics. 1995;96:490–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freed GL. Clark SJ. Curtis P, et al. Breast-feeding education and practice in family medicine. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed GL. Clark SJ. Sorenson J, et al. National assessment of physicians' breast-feeding knowledge, attitudes, training, and experience. JAMA. 1995;273:472–476. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520300046035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller N. Miller D. Chism M. Breastfeeding practices among resident physicians. Pediatrics. 1996;98:434–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arthur CR. Saenz RB. Replogle WH. The employment-related breastfeeding decisions of physician mothers. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2003;44:383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arthur CR. Saenz RB. Replogle WH. Personal breast-feeding behaviors of female physicians in Mississippi. South Med J. 2003;96:130–135. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000051268.43410.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kacmar JE. Taylor JS. Nothnagle M, et al. Breastfeeding practices of resident physicians in Rhode Island. Med Health R I. 2006;89:230–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sattari M. Levine D. Serwint JR. Physician mothers: An unlikely high risk group—call for action. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:353–359. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2008.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattari M. Levine D. Bertram A, et al. Breastfeeding intentions of female physicians. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:297–302. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA. Taylor R. Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank E. STUDENTJAMA. Physician health and patient care. JAMA. 2004;291:637. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank E. Rothenberg R. Lewis C, et al. Correlates of physicians' prevention related practices. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:359–367. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank E. Breyan J. Elon L. Physician disclosure of healthy personal behaviors improves credibility and ability to motivate. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:287–290. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurner LJ. Forman MR. Hundt GL, et al. Maternal recall of infant feeding events is accurate. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46:203–236. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li R. Scanlon KD. Serudla MK. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutr Rev. 2005;63:103–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]