Abstract

Clinical Clostridium difficile isolates of patients with diarrhea or pseudomembranous colitis usually produce both toxin A and toxin B, but an increasing number of reports mention infections due to toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive (A−/B+) strains. Thirty-nine clinical toxin A−/B+ isolates, and 12 other unrelated isolates were obtained from Canada, the United States, Poland, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, and The Netherlands. The isolates were investigated by high-resolution genetic fingerprinting by use of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and two well-described PCR ribotyping methods. Furthermore, the toxin profile and clindamycin resistance were determined. Reference strains of C. difficile representing 30 known serogroups were also included in the analysis. AFLP discriminated 29 types among the reference strains, whereas the two PCR ribotyping methods distinguished 25 and 26 types. The discriminatory power of AFLP and PCR ribotyping among 12 different unrelated isolates was similar. Typing of 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates revealed 2 AFLP types and 2 and 3 PCR ribotypes. Of 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates, 37 had PCR ribotype 017/20 and AFLP type 20 (95%). A deletion of 1.8 kb was seen in 38 isolates, and 1 isolate had a deletion of approximately 1.7 kb in the tcdA gene, which encodes toxin A. Clindamycin resistance encoded by the erm(B) gene was found in 33 of 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates, and in 2 of the 12 unrelated isolates (P < 0.001, chi-square test). We conclude that clindamycin-resistant C. difficile toxin A−/B+ strain (PCR ribotype 017/20, AFLP type 20, serogroup F) has a clonal worldwide spread.

Clostridium difficile has been recognized as a cause of nosocomial diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis. The enteropathogenicity is associated with the production of enterotoxin A (308 kDa) and cytotoxin B (270 kDa) (6, 14). Toxin A is an extremely potent enterotoxin and has been regarded as the primary virulence factor (27, 30). The effect of cytotoxin B depends on the tissue damage caused by toxin A, suggesting that both toxins work synergistically (31).

Toxin A (tcdA) and B (tcdB) genes are located on a pathogenicity island of 19.6 kb also encompassing three other small open reading frames (20). Nontoxigenic, and therefore nonpathogenic, strains of C. difficile contain a 127-bp sequence at this locus (19). The sequence similarity and the position on the island suggests that the tcdA and tcdB genes are the result of gene duplication (15).

Clinical isolates from patients with nosocomial diarrhea or pseudomembranous colitis usually produce both toxin A and B, but an increasing number of reports mention severe infections and outbreaks due to toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive (A−/B+) strains (2, 3, 21, 24, 26, 28). Two types of toxin A−/B+ strains have been identified. The first type is characterized by a large deletion of 5.6 kb in the tcdA gene. The representative strain (8864) causes fluid secretion in rabbit intestinal loops, and it has been suggested that the production of a variant toxin is associated with its enteropathogenicity (8, 29). This variant toxin seems more potent than toxin B and is more similar to Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin (37). The second type is more frequently isolated from human fecal samples, contains a small deletion of 1.8 kb within the repetitive regions of the tcdA gene, and belongs to serogroup F (13).

PCR ribotyping has appeared to be a robust genotyping method. Results can be used for interlab comparison and for the generation of libraries. However, different primers have been proposed, which raises the question of which are most suited for future studies on the epidemiology of C. difficile. The PCR ribotyping by O’Neill as described by Stubbs et al. contains a large library which is used worldwide (38). This method has been modified with primers presumed to be more specific for C. difficile by Bidet et al. (7). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is considered the “gold standard” for genotyping, but due to intensive DNA degradation in some strains, other techniques are preferred. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) has been applied for molecular typing of a variety of bacterial species (1). Recently, AFLP analysis of C. difficile strains showed that its discriminatory power was similar to that of PFGE when tested on 30 clinical isolates. However, reference strains encompassing different reference strains and toxin A−/B+ strains were not included in the analysis (25). Therefore, in the present study we compared AFLP with two different PCR ribotyping methods. Reference strains of C. difficile were included, as were clinical isolates obtained from 7 different countries, with special attention to toxin A−/B+ isolates. Additionally, all strains were characterized for the profiles of the tcdA and tcdB genes and for clindamycin resistance.

(A part of this study has been presented at the 43rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Chicago, Ill., 14 to 17 September 2003 [R. J. van den Berg, C. H. W. Klaassen, J. S. Brazier, E. C. J. Claas, and E. J. Kuijper, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. K-727, p. 366, 2003].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Reference strains of C. difficile encompassing 30 known serogroups were included in this study as control strains: A, A1 to A11, A13 to A17, B, C, E6, F, G, H, I, K, S1 to S4, and X (supplied by M. Delmee, University of Louvain, Brussels, Belgium). Clinical isolates (n = 50) were obtained from 7 different countries (Table 1). The biochemical identification of the strains was confirmed on the basis of the morphology after Gram staining, growth on CDMN agar (C. difficile agar with moxalactam, norfloxacin, and cystein) (4), and a positive aminopeptidase reaction (18). Strains were stored at −80°C in glycerol broth and subcultured onto sheep blood agar medium in an anaerobic atmosphere for usage for 48 h.

TABLE 1.

Sources of clinical isolates used in this study

| Country of origin | Submitting laboratory (city) | No. of isolates | Outbreak isolates (yr) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands | Academic Medical Center (Amsterdam) | 4 | Yes (1997) | 26 |

| Leiden University Medical Center (Leiden) | 8 | No | ||

| Poland | Medical University of Warsaw (Warsaw) | 12 | No | 33 |

| France | Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire Saint-Antoine (Paris) | 8 | No | 5 |

| United States | Northwestern University (Chicago, Ill.) | 2 | No | 21 |

| Canada | University of Manitoba (Winnipeg) | 3 | Yes (1998) | 2 |

| United Kingdom | University Hospital of Wales (Cardiff) | 10 | No | 9 |

| Japan | Gifu University School of Medicine (Gifu) | 3 | No | 24 |

DNA isolation.

DNA was extracted from bacterial cultures on solid media by using QIAamp DNA isolation columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, including a preceding 10-min incubation at 55°C with proteinase K (Qiagen). The final volume of the DNA extracts was 200 μl.

PCR ribotyping. (i) O'Neill method.

The method described by Stubbs et al. (38) was followed. The primers used (PRO primers) for amplification are specified in Table 2. Briefly, amplification reactions were performed in 100-μl final volume containing 50 pmol of each primer, 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Pharmacia), 2.25 mM MgCl2, and 10 μl of DNA. The final products were separated by electrophoresis on 3% Metaphor agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) for 3 h at 200 V. Amplified fragments were visualized by staining the gel for 20 min in a 1-μg/ml ethidium bromide solution. For normalization, a molecular size standard (100 bp; Advanced Biotechnologies, Epsom, United Kingdom) was added every five lanes.

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences of oligonucleotides used for PCR ribotyping and conventional PCR in this study

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Gene | Fragment length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROsa | CTGGGGTGAAGTCGTAACAAGG | ITSc | Variable |

| PROas | GCGCCCTTTGTAGCTTGACC | ||

| PRBsb | GTGCGGCTGGATCACCTCCT | ITS | Variable |

| PRBas | CCCTGCACCCTTAATAACTTGACC | ||

| 282BacS | GAAAARGTACTCAACCAAATA | erm(B) | 639 |

| 283BacAS | AGTAACGGTACTTAAATTGTTTAC | ||

| NKV011 | TTTTGATCCTATAGAATCTAACTTAGTAAC | tcdA | 2,535 |

| NK9 | CCACCAGCTGCAGCCATA | ||

| NK104 | GTGTAGCAATGAAAGTCCAAGTTTACGC | tcdB | 204 |

| NK105 | CACTTAGCTCTTTGATTGCTGCACCT |

PRO, PCR ribotyping by O'Neill method.

PRB, PCR ribotyping by Bidet method.

ITS, internal spacer region.

(ii) Bidet method.

The method as described by Bidet et al. (7) was followed. The primers used for amplification (PRB primers) are specified in Table 2. Briefly, the amplification reactions were performed in a 50-μl final volume containing 25 μl of HotStar Taq master mix (Qiagen), 10 pmol of each primer, and 5 μl of DNA. After an initial enzyme activation step of 15 min at 95°C, the protocol consisted of 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C for denaturation, 1 min at 57°C for annealing, and 1 min at 72°C for elongation. The amplified products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose for 3 h at 85 V.

AFLP.

The conditions for AFLP were as previously described by Klaassen et al. (25). Enzymes EcoRI and MseI were used for restriction. For amplification, the labeled EcoRI primer with 6-carboxy-fluorescein was used, and for selective amplification, the MseI primer contained a G residue as the selective nucleotide.

Analysis of fingerprints.

The results of fingerprinting by the three genotyping methods were stored as tagged image file format files and imported into the BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) for further analysis, with the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean used for clustering. The clustering level of two duplicates was used to delineate different types.

Genetic identification of clindamycin resistance.

Clindamycin resistance was tested by a PCR targeting the erm(B) gene, which codes for macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) resistance, as described previously by Sutcliffe et al. (39) for several pathogenic bacterial species. The primers used (282BacS and 283BacAS) (Table 2) also reacted with C. difficile according to an alignment in BLAST. The sequence of C. difficile erm(B) is more than 97% identical with those of erm(B) genes from other bacterial species (16). Clindamycin-resistant strains were defined as strains with a 639-bp amplicon size.

Genetic identification of tcdA and tcdB profiles.

All strains were tested for the presence of genes tcdA and tcdB. For detection of the tcdA gene, primers NKV011 and NK9 (Table 2) were used as described by Kato et al. (23). Toxin A+ strains showed a 2,535-bp amplicon size, whereas toxin A− strains were defined as strains with a deletion in the tcdA gene of 1.7 or 1.8 kb. The tcdB profile was verified with primers NK104 and NK105 (Table 2) as described previously (24). The presence of a 204-bp fragment was considered indicative for the presence of the tcdB gene. The amplified products were analyzed by separation by agarose gel electrophoresis. Isolates with the 1.8-kb deletion in the tcdA gene and with a tcdB-positive PCR were included in the toxin A−/B+ group. Isolates with other toxin profiles were included in the so-called unrelated group, since no relation with the toxin A− isolates existed.

RESULTS

C. difficile reference strains.

Twenty-one of 30 reference strains were positive for the tcdA and tcdB genes (Table 3). Strains of serogroups A7, A9, A10, A11, and B I, and X did not contain genes for the toxins, whereas those of serogroups F and S3 harbored only the tcdB gene and a variant tcdA gene. The reference strain of serogroup F had the 1.8-kb deletion in the tcdA amplicon, whereas the strain of serogroup S3 had a deletion of approximately 0.8 kb.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of AFLP with PCR ribotyping according to methods of Bidet and O'Neill for 30 reference strains of C. difficile

| Serogroupa | AFLP type | PRBb type | PROc type | tcdA deletion (kb) | tcdB gened |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 1 | NDe | None | + |

| A1 | 2 | 2 | 005 | None | + |

| A2 | 3 | 3 | 002 | None | + |

| A3 | 4 | 4 | 026 | None | + |

| A4 | 5 | 5 | 015 | None | + |

| A5 | 6 | 6 | 063 | None | + |

| A6 | 7 | 7 | 064 | None | + |

| A7 | 8 | 8 | 035 | 2.5 | − |

| A8 | 9a | 9 | 018 | None | + |

| A9 | 10 | 10 | 039 | 2.5 | − |

| A10 | 11 | 10 | 067 | 2.5 | − |

| A11 | 8 | 8 | 035 | 2.5 | − |

| A13 | 12 | 12 | 049 | None | + |

| A14 | 13 | 13 | 103 | None | + |

| A15 | 14 | 14 | 045 | None | + |

| A16 | 15 | 15 | 019 | None | + |

| A17 | 16 | 16 | 153 | None | + |

| B | 17 | 17 | 060 | 2.5 | − |

| C | 18 | 18 | 012 | None | + |

| E6 | 19 | 19 | 046 | None | + |

| F | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + |

| G | 21a | 21 | 001 | None | + |

| H | 22 | 22 | 014 | None | + |

| I | 23 | 23 | 009 | 2.5 | − |

| K | 24 | 22 | 014 | None | + |

| S1 | 25 | 9 | 056 | None | + |

| S2 | 26 | 26 | 050 | None | + |

| S3 | 27 | 27 | 110 | 0.8 | + |

| S4 | 28 | 13 | 103 | None | + |

| X | 29 | 29 | 085 | 2.5 | − |

Designation of reference strains is according to the method of Delmee and Avesani (11).

PRB, PCR ribotyping according to Bidet method.

PRO, PCR ribotyping according to O'Neill method.

PCR for detection of the tcdB gene.

ND, not done.

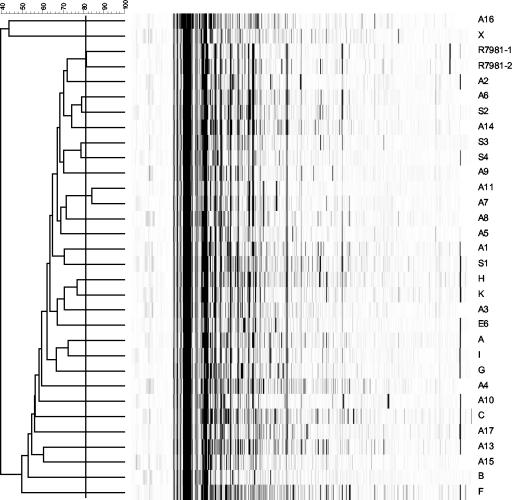

By AFLP, 29 types were distinguished among the 30 reference strains (Fig. 1; Table 3). Strains representing serogroups A7 and A11 were indistinguishable by AFLP. PCR ribotyping by the Bidet method distinguished 25 genotypes in this group. Strains of serogroups A9 and A10 and of serogroups A8 and S1 were indistinguishable by this PCR ribotyping but could be differentiated by PCR ribotyping by the O'Neill method. The latter PCR ribotyping method was able to identify 26 genotypes among the reference strains. Both PCR ribotyping techniques were not able to separate the reference strain of serogroup H from that of serogroup K and the strain of serogroup A14 from that of serogroup S4 (Table 3). As was the case with AFLP, strains of serogroup A7 and A11 could not be differentiated by the two PCR ribotyping methods.

FIG. 1.

AFLP of 30 reference strains after BioNumerics analysis. Designations of the strains are located to the right of the lanes. The clustering level of duplicates R7981-1 and −2 was used to delineate the different types (black line). The numbers at the top indicate the percentage of clustering.

Clinical isolates of C. difficile.

In the group of 50 clinical isolates, one sample (R11092) contained two variant strains. One variant was positive for the tcdA gene, and the second strain contained the 1.8-kb deletion. Both strains were used for analysis. A total of 39 isolates contained the deletion of 1.7 or 1.8 kb in the tcdA gene and were positive for the tcdB gene (Table 4). These strains were included in the toxin A−/B+ group. The remaining 12 isolates were included in the unrelated group. Of the unrelated 12 isolates, 9 were toxin A+/B+. Strain Ned1 was the only toxin A−/B− strain, strain 98-15845 had an amplicon size of approximately 1.9 kb, and strain 98-15323 showed an amplicon size of approximately 2.7 kb for the tcdA gene.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of AFLP with PCR ribotyping according to methods of Bidet and to O'Neill for 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates of C. difficile and 12 unrelated isolates

| Toxin profile | Isolate designation | Submitting laboratory locatione | AFLP type | PRBa type | PROb type | tcdA deletion (kb) | tcdB genec | erm(B) gened |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A−/B+ | Can1 | Winnipeg | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + |

| Can3 | Winnipeg | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | − | |

| Can5 | Winnipeg | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 60 | Paris | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 8864 | Paris | 30 | 30 | 036 | 1.7 | + | − | |

| 98-15632 | Paris | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 98-16948 | Paris | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 98-4318 | Paris | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 99-3050 | Paris | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| Jap1 | Gifu | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| Jap2 | Gifu | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | − | |

| Jap3 | Gifu | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| CD15 | Amsterdam | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| CD16 | Amsterdam | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| CD17 | Amsterdam | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| Ned6 | Leiden | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| Ned7 | Leiden | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | − | |

| 1110/98 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | − | |

| 1745/00 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 205/99 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 2233/98 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 2428/95 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 2601/98 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 2785/97 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 2887/97 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 399/98 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| 592/98 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| P250/00 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| P268/00 | Warsaw | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| CF2 | Chicago | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | − | |

| CF4 | Chicago | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R10205 | Cardiff | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R10430 | Cardiff | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R10542 | Cardiff | 20 | 20 | 047 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R11092-2 | Cardiff | 20b | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R12878 | Cardiff | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R13044 | Cardiff | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R13167 | Cardiff | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| R2140 | Cardiff | 20 | 20 | 017 | 1.8 | + | + | |

| A+/B+ | 98-15323 | Paris | 32 | 32 | 014 | −0.2 | + | − |

| 98-15845 | Paris | 31 | 31 | 045 | 0.6 | + | − | |

| CD21 | Amsterdam | 33 | 33 | 023 | None | + | − | |

| Ned2 | Leiden | 34 | 34 | 005 | None | + | − | |

| Ned3 | Leiden | 24 | 22 | 014 | None | + | − | |

| Ned4 | Leiden | 9b | 9 | 018 | None | + | + | |

| Ned5 | Leiden | 9b | 9 | 018 | None | + | + | |

| Ned8 | Leiden | 21b | 21 | 001 | None | + | − | |

| R11092-1 | Cardiff | 27 | 27 | 110 | None | + | − | |

| R7771 | Cardiff | 27 | 27 | 110 | None | + | − | |

| R7981 | Cardiff | 27 | 27 | 110 | None | + | − | |

| A−/B− | Ned1 | Leiden | 35 | 35 | 085 | 2.5 | − | − |

PRB, PCR ribotyping according to Bidet method.

PRO, PCR ribotyping according to O'Neill method.

PCR for detection of the tcdB gene.

PCR for detection of the ermB gene.

Submitting laboratories were located in Winnepeg, Canada; Paris, France; Gifu, Japan; Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Leiden, The Netherlands; Warsaw, Poland; Chicago, Ill.; and Cardiff, United Kingdom.

Nine genotypes were differentiated among the 12 unrelated isolates by PCR ribotyping by the Bidet method, whereas the PCR ribotyping by the O'Neill method discriminated 8 genotypes (Table 4). With AFLP, the same nine genotypes were distinguished as with Bidet's method. In contrast to AFLP and PCR ribotyping by the Bidet method, PCR ribotyping by the O'Neill method did not discriminate between isolates Ned3 and 98-15323.

AFLP recognized 2 genotypes among 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates. The PCR ribotyping methods of Bidet and O'Neill differentiated 2 and 3 genotypes among toxin A−/B+ isolates, respectively. Isolate R10542 was recognized as a unique type by the O'Neill method of PCR ribotyping but not by the Bidet method of PCR ribotyping and AFLP. The two other genotypes found were comparable to isolate 8864 and the serogroup F-like strains. The toxin A−/B+ isolates from The Netherlands, the United States, Canada, Poland, and Japan all belonged to one genotype, irrespective of the method used. The French isolates harbored 2 genotypes according to all three methods, and those from Wales 2 types according to the O'Neill method of PCR ribotyping, but the AFLP method and the Bidet method of PCR ribotyping could not distinguish between these two.

Of three erm(B)-positive strains also tested in our study, the presence of the erm(B) gene resulted in a clindamycin MIC of ≥256 μg/ml by the E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) (26). Clindamycin resistance was found in 33 of 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates and in 2 of the 12 unrelated isolates (P < 0.001, chi-square test) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the discriminatory power and typeability of AFLP and two different PCR ribotyping methods were compared by using 30 reference strains and 51 clinical isolates of C. difficile. The strains were also characterized for their toxin profiles and susceptibility to clindamycin. AFLP had the highest discriminatory power for differentiation of the reference strains. Concerning the 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates and 12 unrelated strains, the typeability was 100% for all three genotyping methods with a similar discriminatory power.

The AFLP method uses restriction, ligation, and selective amplification on the whole genome. Differentiation can be made due to variation per type in restriction site mutations, mutations in the sequences adjacent to the restriction sites and complementary to the selective primer extensions, and insertions and deletions within the amplified fragments. AFLP for C. difficile has been compared with PFGE by Klaassen et al. (25). Previously, PFGE was found to be more discriminatory than random amplified polymorphic DNA and PCR ribotyping (41). The study by Klaassen also showed that the typeability of AFLP was better than that of PFGE, especially for C. difficile isolates for which PFGE showed DNA degradation. In addition, AFLP was considered faster and easier to perform on small quantities of DNA. The reproducibility of AFLP was found to be similar to that of PFGE (25), which has a much higher reproducibility than restriction enzyme analysis (REA), arbitrary primed PCR, and random amplified polymorphic DNA (10). PFGE data are readily exchangeable between laboratories, and it might be expected that future standardization of techniques for AFLP will also allow interlaboratory comparisons (40).

PCR ribotyping is based on the amplification of the intergenic spacer region between the 16S and the 23S rRNA genes. Every bacterial strain contains several rRNA operons, and there is a strain-dependent variation in the size and number of the 16S-23S intergenic spacer regions. Variation in spacer length is also observed between different copies of the operons in the same genome. Amplification of these regions results in a variety of PCR products whose size and number will vary among different strains, which enables differentiation of these strains. The PCR ribotyping by Stubbs et al. was applied on 2,030 strains, including 1,631 clinical isolates and 133 reference strains, and differentiated 116 genotypes (38). Nineteen serogroups were tested and yielded different banding patterns. This method has been modified with different primers specific for C. difficile by Bidet et al. (7). The latter method tested and discriminated 20 serogroups but was not tested for further discrimination of different strains. Although this PCR ribotyping is a rapid method, there is not yet a large library, as is the case with the O'Neill method, which is used worldwide. In our study, the discriminative power of the PCR ribotyping method of O'Neill on reference strains was higher than the method of Bidet; the main difference was the ability of O'Neill's method to differentiate between strains representing serogroups A9 and A10 and A8 and S1.

The toxin profile of the reference strains of the present study was identical to that of previous studies (12, 34), except for the 3 reference strains (A9, A11, and S3). No background information was found on the toxin profile of reference strains A17 and S2. Reference strains A9 and A11 were found to be negative for the tcdA and tcdB genes, although the presence of both genes has been reported by Rupnik et al. (34). The deletion of approximately 0.8 kb in the tcdA amplicon of the reference strain for serogroup S3 was in contrast with their results as well. In their study, strains from one serogroup sometimes belonged to two or more different toxinotypes. Our discrepant results obtained with these 3 isolates may be explained by the lack of an association of serotyping with toxinotyping. Genotyping of the reference strains showed a higher discriminatory power for AFLP than for both PCR ribotyping methods. The AFLP method was not able to differentiate reference strain A7 from A11, whereas the two PCR ribotyping methods were not able to differentiate between these and other reference strains.

The findings on the toxin profiles of the clinical isolates in our study were in agreement with previously described results (2, 3, 5, 21, 24, 26, 33). Two French isolates, 98-15323 and 98-15845, had variant tcdA genes. Both isolates exhibited a positive result for toxin A detection by enzyme immunoassay, according to the original observation. Based on the original observation, isolate 98-15323 belonged to serogroup H and had an insertion of 200 bp in the fragment amplified with primers NK11 and NK9, whereas isolate 98-15845 was found to have a 600-bp deletion (5). Two variants of C. difficile strain R11092 were isolated from the stored culture. The two variants differed in PCR ribotype and AFLP pattern and therefore were probably derived from a mixed infection.

For the 12 unrelated isolates, the PCR ribotyping by the Bidet method and AFLP were able to discriminate nine types, whereas the PCR ribotyping by the O'Neill method could not discriminate isolate Ned3 (serogroup K) from 98-15323 (serogroup H). PCR ribotyping is unable to discriminate between these two serogroups.

No major difference in the discriminatory power of the three genotyping techniques was observed for toxin A−/B+ isolates. Since a large number of these isolates were apparently clonally related, the discriminatory properties of the various typing methods could not be evaluated with these isolates. Both AFLP and PCR ribotyping by the Bidet method distinguished two types and PCR ribotyping by the O'Neill method distinguished three types. Remarkably, isolate R10542 was recognized as a unique type by PCR ribotyping by the O'Neill method but not by PCR ribotyping by the Bidet method and AFLP. Isolate R10542 was isolated from a patient in Birmingham, United Kingdom, and showed no differences to other toxin A−/B+ isolates in toxin profile or toxinotype (38). Of special interest is the occurrence of one type among 12 Polish toxin A−/B+ isolates. The incidence of toxin A−/B+ strains in Poland has been reported to be as high as 11% among 159 C. difficile strains isolated from patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea (33). Molecular typing of these isolates by PCR ribotyping revealed that 8 of 17 toxin A−/B+ strains had distinct patterns. The 9 others belonged to one PCR ribotype and were included in our comparison together with three new isolates of the same PCR ribotype from Poland. All of these isolates, however, showed identical AFLP patterns, suggesting a clonal spread. Typing of 23 toxin A−/B+ strains isolates from the United Kingdom, United States, and Belgium revealed that a specific toxin A−/B+ clone (PCR type 017, serogroup F, REA type CF4) is widely distributed in Europe and North America (22). PCR ribotype 017 was also the most prevalent type in our study, since 37 of 39 toxin A−/B+ isolates (95%) represented this type. This PCR ribotype was not found among the 12 unrelated isolates. The conclusion that further subtyping of toxin A−/B+ strains is possible is not supported by the genotyping results from this study. However, it would be interesting to compare AFLP typing with toxinotyping. Recently Rupnik et al. found two new toxinotypes (XVI and XVII) among 56 toxin A−/B+ strains (36) by the toxinotyping technique. Interestingly, most toxin A−/B+ strains belonged to toxinotype VIII and PCR ribotype 017 and did not contain the binary toxin cdtB gene (35). However, the two new toxinotypes XVI and XVII both did (36).

A remarkably high percentage of 85% (33 of 39) of toxin A−/B+ C. difficile isolates showed resistance to clindamycin due to MLS resistance by the presence of the erm(B) gene. This high percentage of clindamycin resistance among toxin A−/B+ isolates compared to the unrelated isolates is noteworthy. Resistance to clindamycin increases the risk of C. difficile disease (11). The MLS resistance encoded by the erm(B) gene is found to be incorporated at a site homologous to the C. difficile tcdA gene, which suggests an association between MLS resistance and pathogenicity of toxin A−/B+ strains (32). Evidence is provided by Farrow et al. that the erm(B) gene resides on a transposon and is therefore likely to be transferred between C. difficile isolates (17). The absence of this transposon could lead to clindamycin susceptibility. Another interesting explanation is the recent observation by Johnson et al. (22), who detected two different restriction enzyme patterns (CF2 and CF4) within one PCR ribotype (017). In our study, CF2 and CF4 isolates differed in their susceptibility to clindamycin. This suggests that REA typing could discriminate between clindamycin-susceptible and -resistant strains within PCR ribotype 017.

The present study shows a better discriminatory power of reference strains for the AFLP technique than for the PCR ribotyping methods. However, for toxin A−/B+ C. difficile isolates, the AFLP technique has a discriminatory power similar to that of PCR ribotyping. It can be concluded that clindamycin-resistant C. difficile toxin A−/B+ strains of PCR ribotype 017/20, AFLP type 20, and serogroup F have a clonal worldwide spread.

Acknowledgments

We thank, in alphabetical order, Michelle Alfa (University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada), Frederic Barbut (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire Saint-Antoine, Paris, France), Stu Johnson (Northwestern University, Chicago, Ill.), Haru Kato (Gifu University School of Medicine, Gifu, Japan), and Hanna Pituch (Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland) for kindly providing the isolates used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarts, H. J., L. A. van Lith, and J. Keijer. 1998. High-resolution genotyping of Salmonella strains by AFLP-fingerprinting. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 26:131-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.al Barrak, A., J. Embil, B. Dyck, K. Olekson, D. Nicoll, M. Alfa, and A. Kabani. 1999. An outbreak of toxin A negative, toxin B positive Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a Canadian tertiary-care hospital. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 25:65-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfa, M. J., A. Kabani, D. Lyerly, S. Moncrief, L. M. Neville, A. al Barrak, G. K. Harding, B. Dyck, K. Olekson, and J. M. Embil. 2000. Characterization of a toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strain of Clostridium difficile responsible for a nosocomial outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2706-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aspinall, S. T., and D. N. Hutchinson. 1992. New selective medium for isolating Clostridium difficile from faeces. J. Clin. Pathol. 45:812-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbut, F., V. Lalande, B. Burghoffer, H. V. Thien, E. Grimprel, and J. C. Petit. 2002. Prevalence and genetic characterization of toxin A variant strains of Clostridium difficile among adults and children with diarrhea in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2079-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barroso, L. A., S. Z. Wang, C. J. Phelps, J. L. Johnson, and T. D. Wilkins. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of Clostridium difficile toxin B gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bidet, P., F. Barbut, V. Lalande, B. Burghoffer, and J. C. Petit. 1999. Development of a new PCR-ribotyping method for Clostridium difficile based on ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175:261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borriello, S. P., B. W. Wren, S. Hyde, S. V. Seddon, P. Sibbons, M. M. Krishna, S. Tabaqchali, S. Manek, and A. B. Price. 1992. Molecular, immunological, and biological characterization of a toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strain of Clostridium difficile. Infect. Immun. 60:4192-4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brazier, J. S., S. L. Stubbs, and B. I. Duerden. 1999. Prevalence of toxin A negative/B positive Clostridium difficile strains. J. Hosp. Infect. 42:248-249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen, S. H., Y. J. Tang, and J. Silva, Jr. 2001. Molecular typing methods for the epidemiological identification of Clostridium difficile strains. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 1:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmee, M., and V. Avesani. 1988. Correlation between serogroup and susceptibility to chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, rifampicin and tetracycline among 308 isolates of Clostridium difficile. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 22:325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delmee, M., and V. Avesani. 1990. Virulence of ten serogroups of Clostridium difficile in hamsters. J. Med. Microbiol. 33:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Depitre, C., M. Delmee, V. Avesani, R. L'Haridon, A. Roels, M. Popoff, and G. Corthier. 1993. Serogroup F strains of Clostridium difficile produce toxin B but not toxin A. J. Med. Microbiol. 38:434-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dove, C. H., S. Z. Wang, S. B. Price, C. J. Phelps, D. M. Lyerly, T. D. Wilkins, and J. L. Johnson. 1990. Molecular characterization of the Clostridium difficile toxin A gene. Infect. Immun. 58:480-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichel-Streiber, C., R. Laufenberg-Feldmann, S. Sartingen, J. Schulze, and M. Sauerborn. 1992. Comparative sequence analysis of the Clostridium difficile toxins A and B. Mol. Gen. Genet. 233:260-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrow, K. A., D. Lyras, and J. I. Rood. 2000. The macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinant from Clostridium difficile 630 contains two erm(B) genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:411-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrow, K. A., D. Kyras, and J. I. Rood. 2001. Genomic analysis of the erythromycin resistance element Tn5398 from Clostridium difficile. Microbiology 147:2717-2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia, A., T. Garcia, and J. L. Perez. 1997. Proline-aminopeptidase test for rapid screening of Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammond, G. A., and J. L. Johnson. 1995. The toxigenic element of Clostridium difficile strain VPI 10463. Microb. Pathog. 19:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hundsberger, T., V. Braun, M. Weidmann, P. Leukel, M. Sauerborn, and C. Eichel-Streiber. 1997. Transcription analysis of the genes tcdA-E of the pathogenicity locus of Clostridium difficile. Eur. J. Biochem. 244:735-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, S., S. A. Kent, K. J. O'Leary, M. M. Merrigan, S. P. Sambol, L. R. Peterson, and D. N. Gerding. 2001. Fatal pseudomembranous colitis associated with a variant Clostridium difficile strain not detected by toxin A immunoassay. Ann. Intern. Med. 135:434-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, S., S. P. Sambol, J. S. Brazier, M. Delmee, V. Avesani, M. M. Merrigan, and D. N. Gerding. 2003. International typing study of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile variants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1543-1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato, H., N. Kato, S. Katow, T. Maegawa, S. Nakamura, and D. M. Lyerly. 1999. Deletions in the repeating sequences of the toxin A gene of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175:197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato, H., N. Kato, K. Watanabe, N. Iwai, H. Nakamura, T. Yamamoto, K. Suzuki, S. M. Kim, Y. Chong, and E. B. Wasito. 1998. Identification of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2178-2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klaassen, C. H., H. A. van Haren, and A. M. Horrevorts. 2002. Molecular fingerprinting of Clostridium difficile isolates: pulsed-field gel electrophoresis versus amplified fragment length polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:101-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuijper, E. J., J. de Weerdt, H. Kato, N. Kato, A. P. van Dam, E. R. van der Vorm, J. Weel, C. van Rheenen, and J. Dankert. 2001. Nosocomial outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea due to a clindamycin-resistant enterotoxin A-negative strain. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:528-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Libby, J. M., B. S. Jortner, and T. D. Wilkins. 1982. Effects of the two toxins of Clostridium difficile in antibiotic-associated cecitis in hamsters. Infect. Immun. 36:822-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Limaye, A. P., D. K. Turgeon, B. T. Cookson, and T. R. Fritsche. 2000. Pseudomembranous colitis caused by a toxin A− B+ strain of Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1696-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyerly, D. M., L. A. Barroso, T. D. Wilkins, C. Depitre, and G. Corthier. 1992. Characterization of a toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strain of Clostridium difficile. Infect. Immun. 60:4633-4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyerly, D. M., D. E. Lockwood, S. H. Richardson, and T. D. Wilkins. 1982. Biological activities of toxins A and B of Clostridium difficile. Infect. Immun. 35:1147-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyerly, D. M., K. E. Saum, D. K. MacDonald, and T. D. Wilkins. 1985. Effects of Clostridium difficile toxins given intragastrically to animals. Infect. Immun. 47:349-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mullany, P., M. Wilks, and S. Tabaqchali. 1995. Transfer of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) resistance in Clostridium difficile is linked to a gene homologous with toxin A and is mediated by a conjugative transposon, Tn5398. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 35:305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pituch, H., N. van den Braak, W. van Leeuwen, A. van Belkum, G. Martirosian, P. Obuch-Woszczatynski, M. Luczak, and F. Meisel-Mikolajczyk. 2001. Clonal dissemination of a toxin-A-negative/toxin-B-positive Clostridium difficile strain from patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea in Poland. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:442-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rupnik, M., V. Avesani, M. Janc, C. Eichel-Streiber, and M. Delmee. 1998. A novel toxinotyping scheme and correlation of toxinotypes with serogroups of Clostridium difficile isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2240-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rupnik, M., J. S. Brazier, B. I. Duerden, M. Grabnar, and S. L. Stubbs. 2001. Comparison of toxinotyping and PCR ribotyping of Clostridium difficile strains and description of novel toxinotypes. Microbiology 147:439-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rupnik, M., N. Kato, M. Grabnar, and H. Kato. 2003. New types of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strains among Clostridium difficile isolates from Asia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1118-1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soehn, F., A. Wagenknecht-Wiesner, P. Leukel, M. Kohl, M. Weidmann, C. Eichel-Streiber, and V. Braun. 1998. Genetic rearrangements in the pathogenicity locus of Clostridium difficile strain 8864-implications for transcription, expression and enzymatic activity of toxins A and B. Mol. Gen. Genet. 258:222-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stubbs, S. L., J. S. Brazier, G. L. O'Neill, and B. I. Duerden. 1999. PCR targeted to the 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic spacer region of Clostridium difficile and construction of a library consisting of 116 different PCR ribotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:461-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutcliffe, J., T. Grebe, A. Tait-Kamradt, and L. Wondrack. 1996. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2562-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Dijck, P., V. Avesani, and M. Delmee. 1996. Genotyping of outbreak-related and sporadic isolates of Clostridium difficile belonging to serogroup C. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:3049-3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]