Abstract

Human artificial chromosomes (HACs) represent a novel promising episomal system for functional genomics, gene therapy and synthetic biology. HACs are engineered from natural and synthetic alphoid DNA arrays upon transfection into human cells. The use of HACs for gene expression studies requires the knowledge of their structural organization. However, none of de novo HACs constructed so far has been physically mapped in detail. Recently we constructed a synthetic alphoidtetO-HAC that was successfully used for expression of full-length genes to correct genetic deficiencies in human cells. The HAC can be easily eliminated from cell populations by inactivation of its conditional kinetochore. This unique feature provides a control for phenotypic changes attributed to expression of HAC-encoded genes. This work describes organization of a megabase-size synthetic alphoid DNA array in the alphoidtetO-HAC that has been formed from a ~50 kb synthetic alphoidtetO-construct. Our analysis showed that this array represents a 1.1 Mb continuous sequence assembled from multiple copies of input DNA, a significant part of which was rearranged before assembling. The tandem and inverted alphoid DNA repeats in the HAC range in size from 25 to 150 kb. In addition, we demonstrated that the structure and functional domains of the HAC remains unchanged after several rounds of its transfer into different host cells. The knowledge of the alphoidtetO-HAC structure provides a tool to control HAC integrity during different manipulations. Our results also shed light on a mechanism for de novo HAC formation in human cells.

Keywords: human artificial chromosome, HAC, gene delivery, TAR cloning

INTRODUCTION

Human artificial chromosomes or HACs are an important alternative to conventional virus-based gene transfer vectors. The main advantages of HAC vectors include their maintenance as episomes in human cells, a low level of insertional mutagenesis, and capacity to carry large genes and gene clusters with all their regulatory elements (for example, genes encoding all components of a desired pathway). Therefore, HAC vectors have a great potential to be a useful tool for gene function studies and gene therapy applications 1–6.

In general, there are two types of HACs that are engineered using different approaches. HACs engineered via a “top-down” approach have been constructed by a telomere-directed chromosome truncation technique in homologous recombination-proficient chicken DT40 cells. This procedure generates linear mini-chromosomes of 2–10 Mb that maintain the essential structural and functional properties of a eukaryotic chromosome 7–13. HACs engineered via the “bottom-up” (or de novo) approach have been constructed from 30–240 kb synthetic or natural alphoid DNA arrays that are assembled into megabase-size HACs following their transfection into human cells 14–24. “Bottom-up” HACs may either be linear, if the input DNA contains telomeric repeats, or circular if input DNA lacks telomeric repeats.

Ideally, any vector used for gene delivery must be structurally characterized at the level of primary sequence organisation. Among the “top-down” HACs, a human chromosome 21-derived HAC (21HAC) is the only one with a known structure. It consists of exclusively repetitive elements representing a functional kinetochore and does not contain any endogenous genes 25. Recently it was demonstrated that the 21HAC is capable of carrying large genes such as the 2.4 Mb dystrophin gene, and it was successfully used for gene complementation assays 26. Thus, this HAC vector may have a potential to be used for gene and cell therapies as well as for animal transgenesis.

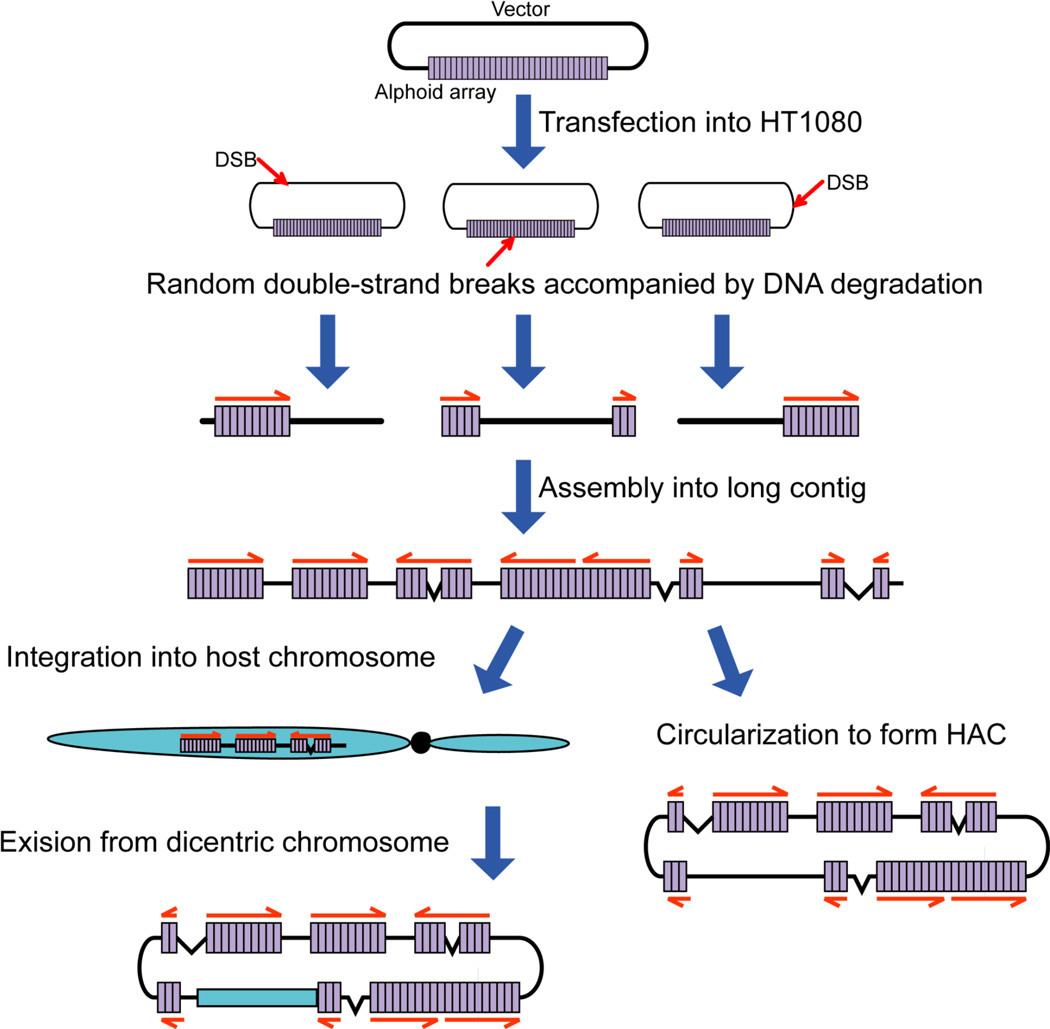

De novo HACs have been constructed by several groups, and their use in gene complementation analysis has been reported 2, 4, 6, 16, 22, 27–31. Analysis of those de novo HACs revealed a concatenated structure of the input alphoid DNA to form large arrays of 1–5 Mb in size (Figure 1a). Because the minimum size of input alphoid DNA arrays is approximately 30 kb, this structure suggests that the exogenous DNA has been amplified 30–150 times during HAC formation 17, 24, 29, 32, 33. However, as-yet, no de novo constructed HAC has been physically mapped in detail.

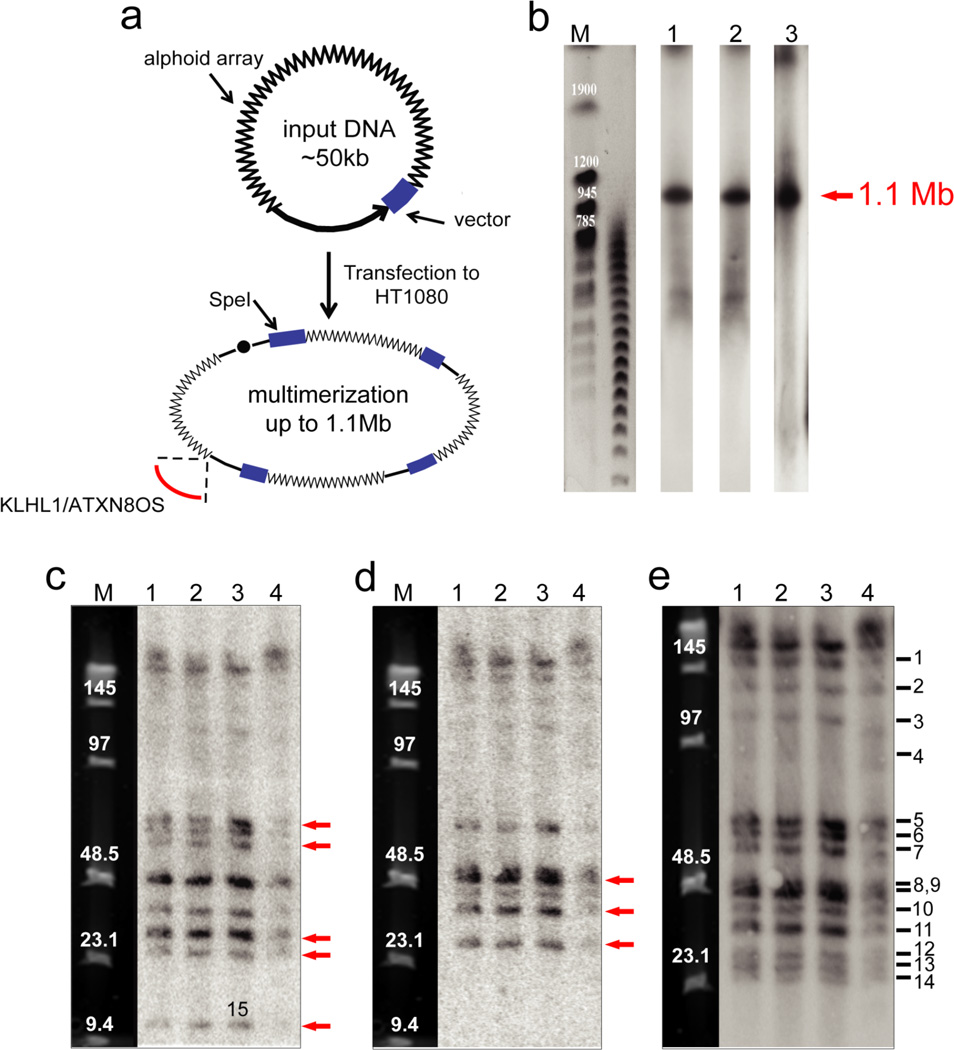

Figure 1.

Structural analysis by restriction enzyme digestion and CHEF of the alphoidtetO-HAC in human, hamster and chicken cells. (a) Diagram illustrating multimerization of input DNA during de novo HAC formation in human cells. Input DNA consists of 40 kb alphoid DNA and 10 kb vector sequence. Chromosome 13 fragment carrying the KLHL1/ATXN8OS genes was captured during formation of the alphoidtetO-HAC. (b) Determination of the size of the multimerized input DNA in the alphoidtetO-HAC in chicken DT40, hamster CHO and human HT1080 cells. Genomic DNA possessing the HAC was digested with PmeI and separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis (range 200–1500 kb). The transferred membranes were hybridized with a radioactively labeled tetO-specific alphoid probe. A single1.1 Mb fragment was detected. Its size was determined by comparison with the DNA size standard, S. cerevisiae chromosomes. Lane 1 – the HAC in chicken cells; lane 2 – the HAC in hamster cells; lane 3 – the HAC in human cells. (c) Analysis of the alphoidtetO-HAC digested by SpeI. Genomic DNA possessing the HAC was digested with SpeI endonuclease and separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis (range 10–70 kb). The transferred membranes were hybridized with either vector probe 3 (c), vector probe 1 (d) or tetO-alphoid (e) probe. Red arrows indicate to the fragments that are specific to either probe 1 or probe 3. Lane 1 – the HAC in DT40 cells; lane 2 - the HAC in CHO cells; lane 3 - the original alphoidtetO-HAC in human HT1080 cells; lane 4 - the HAC transferred back to human cells from CHO cells. M - Pulse Markers.

Recently we described a novel HAC engineered from a synthetic alphoidtetO DNA array. This array is based on several thousand copies of a dimeric alphoid repeat in which one monomer contains a 47 bp tetracycline operator (tetO) sequence in place of the CENP-B box 34, 35. The alphoidtetO-HAC has been used for delivery of full-length genes and correction of genetic deficiencies in human cells 36. Because tetO is bound with very high affinity and specificity by the tet repressor (tetR), the tetO sequences in the HAC can be targeted with tetR fusion proteins that can be designed to inactivate the centromere and induce HAC loss 34,37. As a result, the alphoidtetO-HAC has a conditional centromere, whose activity can be modulated by co-expression of appropriate tetO binding proteins.

This unique feature of the alphoidtetO -HAC enables researchers to control for phenotypic changes attributed to expression of HAC-encoded genes by “curing” cells of the HAC through inactivation of its kinetochore in proliferating cell populations. In such experiments, phenotypic alterations due to genes expressed from the HAC should be reversed. The HAC is also potentially useful for experiments that require transient expression of a cloned gene(s) of interest, e.g. for the generation of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. In addition to its use for gene transfer experiments, the alphoidtetO-HAC has been used to study kinetochore assembly and function. The targeting of a wide range of proteins into the functional kinetochore of the alphoidtetO-HAC as fusions with tetracycline repressor allows the specific manipulation of the protein complement of the HAC kinetochore in vivo while leaving all natural kinetochores unperturbed. This approach identified a characteristic pattern of histone modifications within the kinetochore and revealed that a dynamic balance between centromeric chromatin and heterochromatin is apparently essential for vertebrate kinetochore activity 34, 37–39. Thus, the alphoidtetO-HAC has a number of advantages over other gene delivery HAC vectors.

In this study, we defined the organization of the alphoid DNA array in the alphoidtetO-HAC. This information will enable us to monitor the structural integrity of the HAC during gene loading and transfer into different host cells. Our results lead us to suggest a mechanism for de novo HAC formation in human cells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The AlphoidtetO-HAC Contains a ~1.1 Mb Alphoid DNA Array That is Stable Through HAC Transfer into Different Cells

The alphoidtetO-HAC was constructed in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells from a 40 kb synthetic alphoidtetO DNA array 34 that was cloned into the 10 kb YAC/BAC vector RCA/SAT43 40. Based on its size as determined by fluorescence microscopy and qPCR analysis, formation of the alphoidtetO-HAC was known to be accompanied by some amplification of the input DNA 34 (Figure 1a). Formation of the alphoidtetO-HAC was also accompanied by the capture of a DNA fragment from a gene-poor region of the q arm of chromosome 13 carrying the 407 kb KLHL1 gene (MIM 605332) and the 32 kb ATXN80 gene (MIM 603680) with genomic coordinates (hg19) 70,274,724 –70,682,624 and 70,681,344 – 70,713,884, correspondingly. Detailed microarray and RT-PCR analysis failed to detect specific transcription from the two brain-specific genes present in this segment of chromosome 13 in HAC-bearing cells or to reveal any requirement for this region in HAC propagation. The present MS focuses on the structure of the of the synthetic alphoid DNA array in the HAC, and detailed analysis of the chromosome 13 fragment will be presented elsewhere.

To date, neither the level of input DNA multimerization nor its detailed structural analysis has yet been performed for any de novo HAC. Such analysis in the original cell line could potentially be problematic because during transfections, input DNA is often integrated into the host chromosomes. Therefore, the alphoidtetO-HAC was transferred from HT1080 to different host cells via microcell-mediated cell transfer (MMCT) in order to “purify” the HAC away from the endogenous human chromosomes of the original transfected cell. The alphoidtetO-HAC was first moved into chicken DT40 cells, in which a single 10 kb loxP gene loading cassette was inserted into BAC vector sequences by homologous recombination 35. It was then moved into Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, where a GFP transgene was loaded into the loxP site. Ultimately, the HAC was moved back into human HT1080 cells. The presence of the autonomous form of the HAC in each of these host cells was confirmed by FISH analysis 35 and data not shown.

To determine the size of the multimerized alphoid DNA array, chromosome-size genomic DNA was prepared in agarose plugs from cells harboring the alphoidtetO-HAC, cut with PmeI endonuclease, separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis, and hybridized with an alphoidtetO probe (Table 1). PmeI cleaves the chromosome 13 fragment more than 40 times but does not cut the alphoid DNA or RCA/SAT43 vector. As seen from Figure 1b, Southern blot-hybridization revealed a single 1.1 Mb band corresponding to the continuous alphoid DNA array in the HAC. One band of 1.1 Mb in size was also observed on the Southern blot after PacI digestion (data not shown). This endonuclease does not cut the input DNA but its recognition sites are abundant in the chromosome 13 fragment. We conclude that de novo alphoidtetO-HAC formation was accompanied by an approximately 22-fold multimerization of the input DNA. Because the same size of the amplified alphoidtetO array was detected in all cell types analyzed, the gross structure of the HAC must be stably maintained in the recipient cells after microcell-mediated transfer.

Table 1.

Primers Used to Develop the Probes for Southern Blot Hybridization and for PCR Analysis

| Oligonucleotide name | Sequence | Size of PCR product (in bp) | Positions in RCA/SAT43 vector* |

|---|---|---|---|

| tetO-alphoid probe | |||

| tetO-R | 5’-CCACTTGCACATTCTACAAATAGTGTG-3’ | 276 | n/a |

| tetO-F | 5’-GAGAAACTTCTTTGTGATGTTTGCATTC-3’ | ||

| Vector probe 1 | |||

| 1F | 5’-GTCGACAGCGACACACTTG-3’ | 200 | 1–200 |

| 1R | 5’-AAGGGCAAGTATTGACATGTCG-3’ | ||

| Vector probe 3 | |||

| 3F | 5’-GGGCAATTTGTCACAGGG-3’ | 201 | 4243–4443 |

| 3R | 5’-ATCCACTTATCCACGGGGAT-3’ | ||

| Vector probe 5 | |||

| 5F | 5’-CGCATTTTCTTGAAAGCTTTG-3’ | 199 | 9701–9900 |

| 5R | 5’-TTTAAATAATCGGTGTCACTACATAAG-3’ | ||

| Vector chloramphenicol gene (Cm) | |||

| Clm-F | 5'-CGGAAGATCACTTCGCAGAA-3' | 639 | 5291–5930 |

| Clm-R | 5'-CAGGGATTGGCTGAGACGAA-3' | ||

| Linker fragment homologous to RSA/SAT43 vector sequence upstream and downstream of the SpeI site | |||

| Spe/HAC-R | 5’-AGGCATCTAACCTTCATGAGCA-3’ | 262 | 660–922 |

| Spe/HAC-F | 5’-CATCAGGGTGCTGGCTTTTC-3’ | ||

The size of the RCA/SAT vector is 10,119 bp. Position of SpeI site in the vector is 812

Alphoid DNA Array in the AlphoidtetO-HAC Has an Irregular Structure

To analyze whether the megabase-size alphoid array in the HAC consists simply of tandem repeats of the input DNA or has undergone structural rearrangements, Southern blothybridization was carried out with genomic DNA digested by SpeI endonuclease. This nuclease cuts the vector sequence once but does not have a recognition site in the alphoid DNA array (Figure 1a). The same three cell lines described above plus the original human HT1080 cell line (clone AB2.218.21) in which the alphoidtetO-HAC was formed34 were used for analysis. SpeI-digested genomic DNA was separated by CHEF and hybridized with three different probes. One probe was specific to the tetO-alphoid sequence: two others - vector probe 1 and vector probe 3, are specific for different parts of the RCA/SAT43 vector (Table 1). If the HAC was formed by simple concatenation involving rolling-circle amplification of the input DNA and had not undergone structural rearrangements, only one band of 50 kb in size would be observed on the Southern blot after SpeI digestion. Instead, multiple bands of different sizes were detected with all three probes. Hybridization with the tetO-alphoid probe revealed 14 fragments from 25 to 150 kb in size (Figure 1e). This suggests that the HAC DNA was assembled from differently rearranged input DNA molecules.

Hybridization with vector probe 1 revealed 10 fragments while hybridization with vector probe 3 revealed 11 fragments. The latter correspond to the bands visualized by the tetO-alphoid probe (Figure 1c,d). Notably some SpeI-fragments are negative for vector probe 3 while positive for vector probe 1 and vice versa (bands 5, 7, 12, 14, 15 are probe 3-specific and bands 8, 10, 13 are probe 1-specific). This indicates that some copies of the vector sequence suffered deletions during HAC formation. Moreover, the intensity of the individual bands differs, indicating that the fragments are present in the HAC in different copy numbers. The highest intensity corresponds to the band of approximately 50 kb in size, corresponding to the size of the un-rearranged input DNA. Interestingly, the smallest band (band 15) is not visualized with the tetO-alphoid probe, suggesting that this band contains either only 1–2 copies of alphoid DNA monomer or vector sequences only. It is worth noting that the sum of sizes of all 15 fragments is about 1.1 Mb when corrected for band intensities. This corresponds to the size of the mega-base array determined by PmeI digestion. This band pattern is maintained through the HAC transfer from cell to cell, indicating that once assembled, the HAC DNA structure appears to be stable.

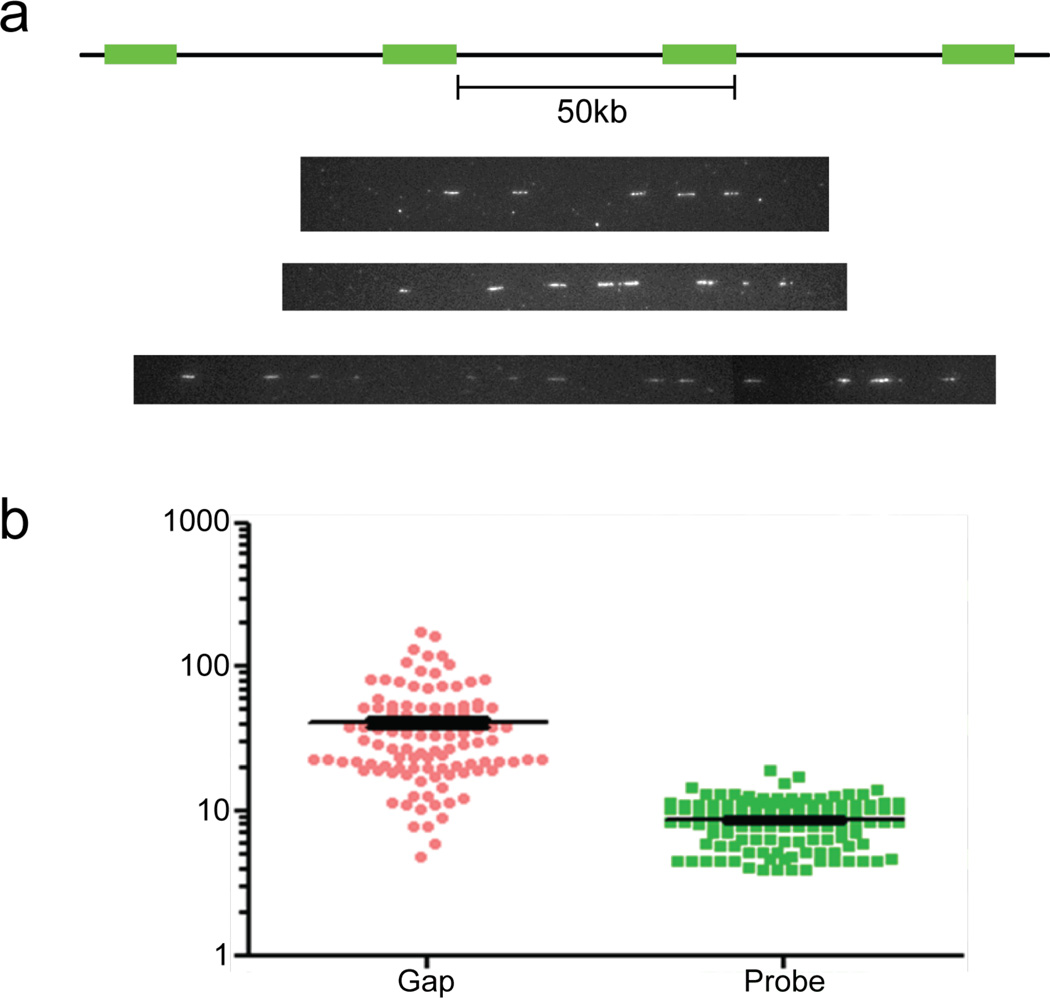

The structural rearrangements of the input alphoidtetO-HAC sequence were confirmed independently by fiber-FISH analysis. DNA fibers were prepared from HT1080 human cells containing the original HAC (clone AB2.218.21) and hybridized using the RCA/SAT43 vector DNA as a probe. Representative images are shown in Figure 2a. The lengths of the FISH signals and gaps are presented in Figure 2b. This analysis revealed that the length of the gaps (corresponding to the alphoidtetO DNA arrays) varies between 5 and 200 kb, with the most frequently observed gap being about 40 kb. This corresponds to the size of alphoid array in the input DNA. The length of the vector signal varies between 5 and 20 kb, with a mean of about 10 kb, corresponding to the length of the RCA/SAT43 vector. These results are in agreement with the pattern of the fragments observed on the Southern blots.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the alphoidtetO-HAC by fiber-FISH. Single DNA fibers from human HT1080 cells containing the HAC were stretched on silanized coverslips. HAC DNA was detected by FISH using the 10 kb RCA/SAT43 vector DNA as a probe. Representative images are showed in (a). All the FISH signals (white short lines) are vector DNA and the gaps between the FISH signals are alphoid-satellite repeat sequences. (b) The length of the FISH signals and gaps are shown as a graph. Ordinate shows the length distribution for vector sequence (probe) and for sequence between neighboring vector signals (gap) in kb.

To summarize, the alphoid DNA array in the alphoidtetO-HAC has a mosaic structure, indicating that de novo HAC formation is accompanied by rearrangements of the input DNA molecules before or during their assembly into the HAC.

The AlphoidtetO-HAC Consists of Direct and Inverted Alphoid DNA Repeats

Southern blot hybridization results presented above neither determine the orientation of the alphoidtetO DNA fragments relative to each other in the HAC nor their physical structure. To address these questions, the SpeI-digested HAC fragments identified by Southern blot-hybridization were isolated by transformation-associated recombination (TAR cloning) in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae 41, 42. This isolation was simplified by the presence in the RCA/SAT43 vector of a YAC cassette with a HIS3 selectable marker plus ARS and CEN sequences. Because linear DNA fragments are circularized very efficiently when homologous linker DNA is added 43, the transformation mixture also included a 262 bp linker-fragment homologous to the vector sequence upstream and downstream of the SpeI site (Table 1). Homologous recombination between the SpeI-digested HAC fragments and the linker fragment resulted in the rescue of the fragments as circular YAC molecules (Figure 3a).

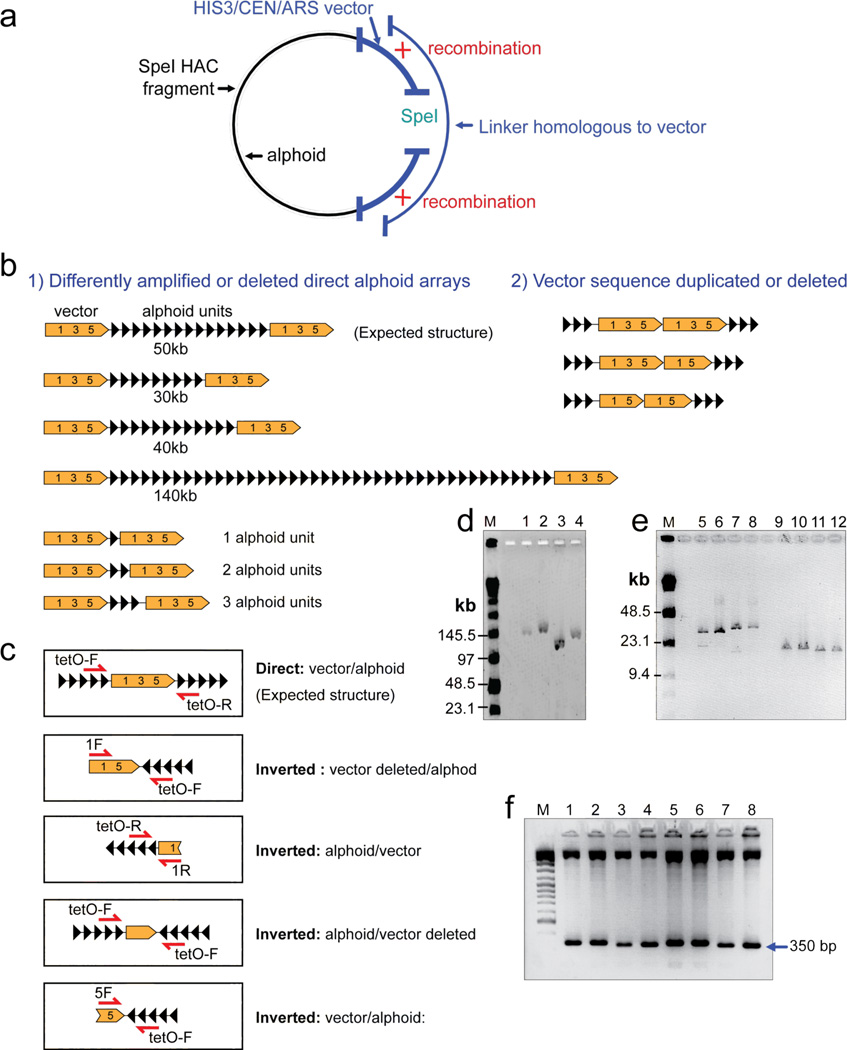

Figure 3.

Structural analysis of the HAC fragments rescued by TAR cloning in yeast. (a) A scheme of rescue of the SpeI HAC fragments as circular molecules by transformation-associated homologous recombination in yeast. The vector part of input DNA contains a YAC cassette with an yeast selectable marker HIS3, ARS and CEN sequences. In vivo recombination between a HAC fragment and a linker results in a circular molecule. The clones with the circularized fragments were selected on SD-His− medium. Alphoid DNA is marked in black. Vector DNA is marked in blue. (b) Schematic diagram of the rearranged input DNA molecules rescued in yeast and E. coli. Several examples of SpeI-fragments rescued in yeast are shown. (c) PCR analysis of direct and inverted alphoid sequences in the rescued YAC clones and in the alphoidtetO-HAC propagated in chicken cells. A single tetO-F primer amplifies a part of the vector sequence (positions 2,913–3,300 in the RCA/SAT/43 vector) flanked by inverted alphoid repeats. (d, e) Characterization of the rescued clones in a BAC form. BAC DNAs were isolated from 12 randomly chosen clones, digested by SpeI for linearization, separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis (lanes 1, 2, 3, 4 with range 20–300 kb; lanes 5–12 with range 10–70 kb), and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. M - Pulse Marker™ 0.1–200 kb (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). (f) The tandem repeat structure of alphoid arrays is confirmed by StuI restriction enzyme digestion (350 bp alphoid dimer unit); the upper bands represent vector fragments.

SpeI-digests of genomic DNA prepared from DT40 cells carrying the HAC were co-transformed along with the linker-fragment into yeast. Transformants were selected on synthetic medium without histidine using freshly prepared yeast spheroplasts as described previously 42. A total of 52 His+ transformants were obtained, of which 25 were randomly selected for further analysis.

To determine the size and structure of the rescued molecules, genomic DNA from yeast transformants was prepared in agarose plugs, digested by SpeI, separated in CHEF gels and hybridized with the alphoidtetO-specific probe (Table 1). The size of isolated YACs varied between 10 and 150 kb (Table 2), corresponding to the sizes of the SpeI-fragments identified by genomic Southern blot-hybridization. To examine the extent to which the alphoidtetO DNA had been truncated or extended in individual arrays, a pair of primers, 5F/1R, was used in order to amplify the junction between the end and the beginning of two vector sequences. PCR products were obtained for three clones, #6, #11 and #23 (Table 2). Sequencing of those PCR products revealed one, two or three alphoid repeats between the flanking vector sequences. This is indicative of an extremely high degree of truncation of the alphoidtetO DNA in those arrays (Figure 3b). Arrays in other clones were presumably too long to yield PCR products in this analysis.

Table 2.

PCR-Analysis of YAC Clones carrying SpeI-fragments for the Presence of Inverted Alphoid DNA Arrays and Deletions of Vector Sequences

| Vector sequnece | Direct orientation of alphoid arrrays | Inverted orientation of alphoid arrays | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone | 1F/1R | 3F/3R | 5F/5R | 1R/tetO-F1 | 5F/tetO-R1 | Clm-F/Clm-R | 5F/1R | YAC Size | 1F/tetO-F1 | tetO-R1/1R | 5F/tetO-F1 |

| 1 | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 2 | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 40kb | − | − | − |

| 5 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | 25kb | − | − | − |

| 6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10kb (1 unit)** | − | − | − |

| 7a | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | n/d | + | + | + |

| 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 30kb | − | − | − |

| 9* | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | n/d | + | + | − |

| 10 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 11 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | 10 kb (3 units) | − | − | − |

| 12a | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | n/d | − | + | + |

| 13 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 100kb | − | − | − |

| 14 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 140kb | − | − | − |

| 15a | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | n/d | − | − | + |

| 16 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 17 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 145kb | − | − | − |

| 18 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 19 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 130kb | − | − | − |

| 20 | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 21 | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 22a | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | n/d | + | + | + |

| 23 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 10 kb (2 units) | − | − | − |

| 24 | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

| 25 | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | 50kb | − | − | − |

Inverted orientation of alphoid DNA towards a vector sequence was confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA purified from in DT40 cells containing the HAC.

In parentheses a number of alphoid DNA monomers flanked with vector sequences is shown.

To check whether portions of the vector sequences had also been lost in the rescued SpeI-fragments, we designed a set of primers for different parts of the vector (Table 1). The results of that PCR analysis are summarized in Table 2. Eleven clones were positive for sequences corresponding to probes 1, 3, 5 and the Cm gene. The entire vector sequence is likely intact in those clones. One rescued clone (#9) was positive only for the probe 1 sequence and three clones (#10, #15 and #18) were positive only for probe 3 sequence. Eleven other analyzed clones were positive for sequences corresponding to either two or three of the above probes. Thus, parts of the vector sequence had been deleted in those YAC clones.

To determine the orientation of the alphoid DNA relative to the vector sequence in the TAR-isolated clones, we designed a set of primers that would specifically amplify only the direct or inverted orientation (Table 1). For this purpose, one primer was chosen from one end of the vector sequence and another primer - from a synthetic alphoidtetO DNA dimer. PCR amplification using the “direct” pair of primers, 1R/tetO-F and 5F/tetO-R, i.e. specific for the direct configuration (as in the input vector), worked for 21 clones. In contrast, PCR reactions using the inversion-specific pair of primers 1F/tetO-F, tetO-R/1R and 5F/tetO-F worked for four clones (#7, #12, #15 and #22), suggesting that in the latter, the alphoidtetO array had been inverted relative to the vector (Table 2). Sequencing of PCR products confirmed the predicted direct or inverted orientation of alphoid DNA relative to the vector in these clones (Figure 3b,c).

These results strongly suggest that ~15% of the alphoid DNA arrays had been inverted in the HAC and that the original 40 kb alphoid DNA array containing ~ 120 repeat units may be truncated up to few repeats. However, it was important to carry out control experiments to exclude that these rearrangements have occurred during TAR rescue of the SpeI-fragments in yeast. For this purpose, the same sets of primers were used to amplify the alphoidtetO-HAC sequences directly from genomic DNA isolated from DT40 cells containing the HAC. Most of these primer pairs gave more than one PCR product. These DNA fragments were TOPO-cloned and sequenced. Sequencing confirmed the presence of both direct and inverted alphoid DNA arrays in the HAC. In addition, sequencing of PCR products obtained using the primer pair 5F/1R confirmed that alphoid DNA in the HAC may be deleted to yield minimal cores of one, two or three alphoidtetO repeats. These PCR products presumably correspond to the smallest band (band 15) identified on the genomic blot (Figure 1c). We also obtained PCR products using the single primer tetO-F (Table 1), which should amplify only alphoid repeats that were inverted relative to the vector. Sequencing of those PCR products revealed two inverted alphoid DNA units separated by a truncated vector fragment of 387 bp (corresponding to bp 2,913–3,300 in the 10 kb RCA/SAT/43 vector) (Figure 3c).

The RCA/SAT43 vector used for construction of synthetic alphoid arrays also contains a BAC sequence that allows transfer of the TAR-rescued molecules from yeast to Escherichia coli. YAC clones described above that were PCR-positive for the Cm gene (Table 2) were transferred from yeast to bacterial cells and rescued as BACs. The size of those BAC clones determined by SpeI digestion and CHEF gel separation varied from 10 to ~150 kb (Figure 3d,e), corresponding to the size range of the YAC clones in yeast. To confirm that inserts in the isolated BACs are represented by pure alphoidtetO DNA, the BAC DNAs were digested with the restriction endonuclease StuI, which cleaves each alphoidtetO dimer at a unique site. In all cases, this treatment revealed the predicted ~350 bp band, corresponding to individual copies of the dimeric tetO-containing repeat unit (Figure 3f).

To summarize, analysis of the alphoidtetO- HAC SpeI-fragments revealed that they consist of input DNA sequences of different size assembled into the 1.1 Mb alphoid contig. In addition, it was found that alphoid DNA arrays in the HAC are in both direct and inverted orientations.

Integrity of Functional Domains in the AlphoidtetO-HAC After Multiple Rounds of MMCT

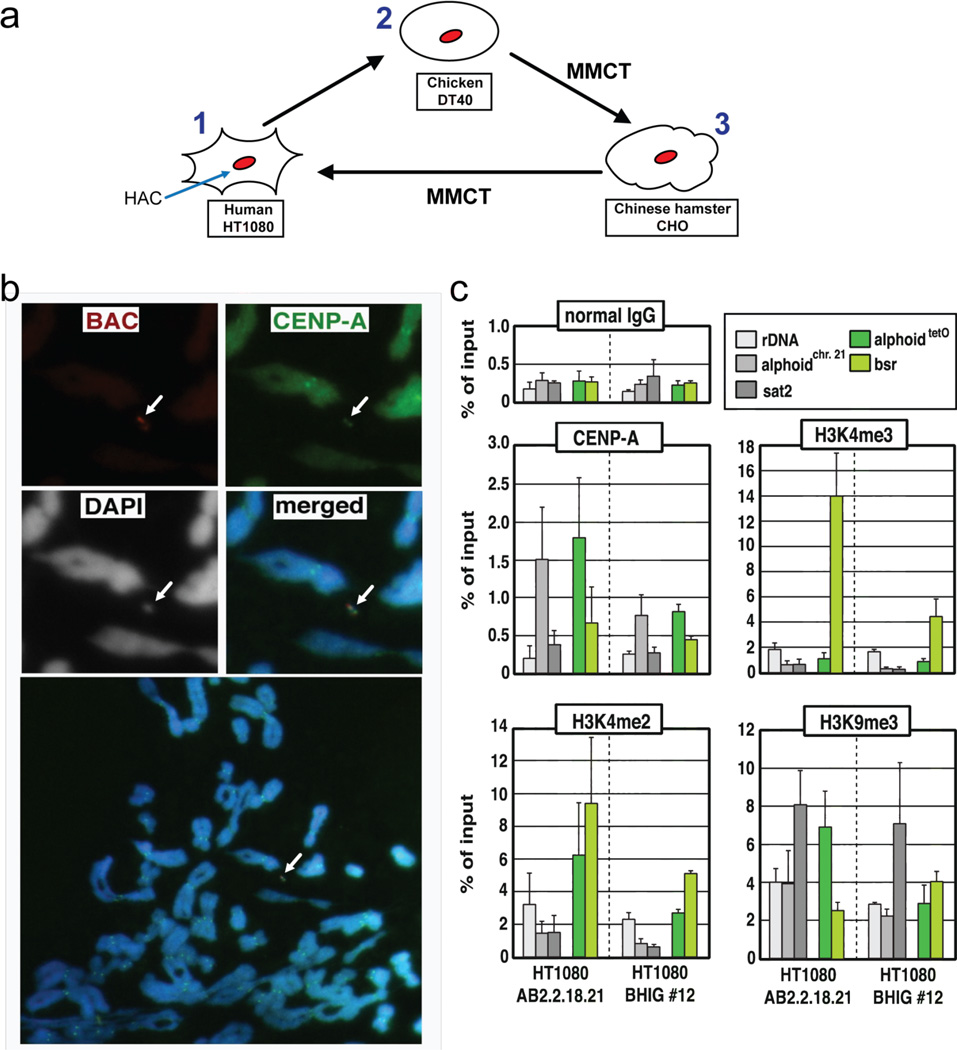

The alphoidtetO HAC is mitotically stable in DT40, CHO and HT1080 cells 34, 35. To check whether the MMCT procedure affects the epigenetic status of the HAC centromere, we analyzed the chromatin structure of the alphoidtetO-HAC in human HT1080 cells after multiple steps of micro-cell mediated transfer (Figure 4a). Immuno-FISH analysis confirmed the assembly of CENP-A chromatin on the HAC sequences in both the starting and final derived cell lines (Figure 4b). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis also showed a pattern of histone H3 modifications similar to that of the original alphoidtetO-HAC clone (AB2.2.18.21 34) for CENP-A chromatin as well as H3K4me3 (a marker for promoter-proximal transcriptionally active chromatin), H3K4me2 (a marker for open chromatin) and H3K9me3 (a marker for heterochromatin) on alphoidtetO DNA (Figure 4c). These results indicate that the alphoidtetO-HAC retained the original histone modification status of its kinetochore after several steps of MMCT.

Figure 4.

Integrity of the functional domains in the alphoidtetO-HAC that underwent three rounds of MMCT transfer. (a) The alphoidtetO-HAC was first transferred to chicken DT40 from human HT1080. A loxP cassette was inserted into the HAC by homologous recombination in DT40 cells. Then the HAC was transferred to CHO cells. From CHO cells the HAC was transferred back to HT1080. (b) Immuno-FISH analysis of metaphase chromosome spreads containing the alphoidtetO-HAC in human HT1080 cells. Cells with the alphoidtetO-HAC (clone BHIG#12) were used for analysis. Immunolocalization of the centromeric protein CENP-A on metaphases was performed by indirect immunofluorescence with anti–CENP-A antibody and Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody (green). HAC-specific DNA sequence (RCA/SAT43 vector) was used as a FISH probe to detect the HAC (red). CENP-A and BAC signals on the HAC overlap one another. (c) ChIP analysis of CENP-A assembly and modified histone H3 at the alphoidtetO-HAC. The results of ChIP analysis using normal mouse IgG (top left panel), antibodies against CENP-A (middle left panel), dimethylated histone H3 Lys4 (H3K4me2, bottom left panel), trimethylated histone H3 Lys4 (H3K4me3, middle right panel) and trimethylated histone H3 Lys9 (H3K9me3, bottom right panel). The assemblies of these proteins on the original alphoidtetO-HAC in the AB2.2.18.21 cell line (left), the alphoidtetO-HAC in the BHIG#12 cell line (right) are shown. The bars show the percentage recovery of the various target DNA loci by immunoprecipitation with each antibody to input DNA. Error bars indicate s.d. (n= 2 or 3). Analyzed loci were rDNA (5S ribosomal DNA), alphoidchr.21 (centromeric alphoid DNA of chromosome 21), sat2 (pericentromeric satellite 2), alphoidtetO (alphoid DNA with tetO motif on tetO alphoid HAC), Bsr (the marker gene in BAC vector region of tetO alphoid HAC). Comparison of the enrichment of tetO-alphoid DNA and the endogenous chromosome 21 alphoid DNA by CENP-A, H3K4me2, H3K4me3 in BHIG#12 and AB2.2.18.21 cells was carried out by calculations of the ratio between IPed tetO-alphoid DNA in the HAC and IPed endogenous chromosome 21 alphoid DNA for each cell line. As seen in Figure S1 (Supporting Information), a relative enrichment of CENP-A, H3K4me2, H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 on tetO-alphoid DNAs in BHIG#12 cells is not different from that observed in AB2.2.18.21 cells. This indicates that kinetochore regions in the HAC did not change after multiple steps of HAC transfer via MMCT.

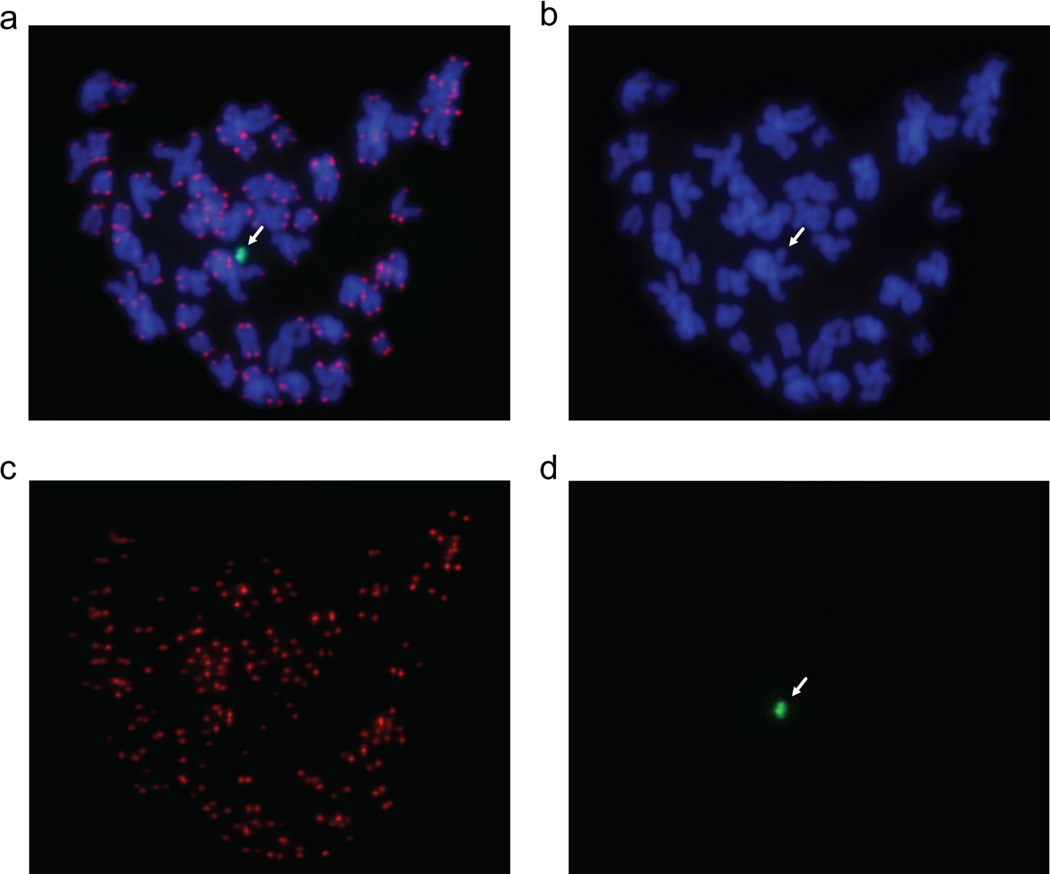

The original alphoidtetO-HAC (AB2.2.18.21 34) was generated from input DNA lacking telomeres and was therefore predicted to be circular 2–6, 21. Indeed, a telomere-specific probe does not hybridize with the HAC (data not shown). In this study, we tested whether the HAC remains circular after several steps of MMCT. Telomere-specific and tetO- specific PNA probes were designed for FISH analysis, as described in Methods. The first probe revealed strong telomeric signals on all human chromosomes except for the HAC (Figure 5a,c), which was specifically detected by the alphoidtetO probe (Figure 5a,d). These results strongly suggest that the alphoidtetO-HAC circular structure is stably maintained after several steps of MMCT.

Figure 5.

FISH analysis of the alphoidtetO-HAC in HT1080 cells using the telomere probe after several steps of MMCT transfer. FISH analysis was performed using PNA labeled probes for telomeric (red) and tetO-alphoid sequences (green). Panels c and d represent metaphase spreads hybridized with telomeric and tetO-alphoid probes, correspondingly. Panel a represents merged images of panels b, c, and d.

Summary and Conclusions

The alphoidtetO-HAC engineered from synthetic alphoidtetO DNA has the potential to be developed into an advanced vector for delivery and expression of full-length genes and gene clusters. The HAC, which possesses a conditional centromere that can be turned off by targeting certain tetO-binding proteins, offers an unprecedented opportunity for genomic manipulation of cells, since it can be eliminated from cell populations if desired. In addition to its use for gene transfer experiments, the alphoidtetO-HAC has been used to study kinetochore assembly and function 34, 37–39.

Given the multiple potential applications of the alphoidtetO-HAC, we here present data on its physical organization using a combination of different methods. Analysis showed that HAC formation was accompanied by multimerization of the input synthetic alphoidtetO-array, similar to that previously reported for HACs assembled from natural alpha-satellite DNA substrates 16, 17, 19–23. The size of the amplified synthetic alphoid DNA mega-array in the alphoidtetO-HAC is ~ 1.1 Mb. This corresponds to a ~ 22-fold amplification of the input DNA. Analyses revealed that a significant fraction of the input DNA had been rearranged during HAC formation. A set of the mature arrays was isolated in yeast using direct cloning of HAC DNA fragments by recombinational cloning in yeast (TAR cloning) 41, 42, then moved to E. coli and physically characterized. The size of the major blocks of the alphoidtetO DNA in the HAC varies from 25 to 150 kb. The spectrum of the fragments rescued by TAR cloning corresponded to the spectrum of multiple bands seen on Southern blots after genomic digestion by an endonuclease that cuts the input DNA only once. This phenomenon seems general, as similar irregular-size Southern profiles suggesting rearrangements in the input DNA have been reported for several de novo formed HACs 17, 27, 29, 32, 33. However, the detailed structural basis of the multiple bands in those HACs had not been investigated. In this study, we show that those bands correspond to rearranged input DNA with deleted or amplified alphoid and vector DNAs. Our analysis also detected blocks of alphoid DNA arrays organized as inverted repeats in the HAC.

Based on analysis of the alphoidtetO-HAC structure, we propose a mechanism for its de novo formation in human cells from a synthetic alphoid DNA array (Figure 6), initial steps of which may be general for all HACs developed from different alphoid DNA arrays. This mechanism is very similar to those proposed to describe the fate of exogenous DNA following its transfection into mammalian cells – a process known to be accompanied by a high frequency of structural rearrangements, including both degradation and generation of concatamers 44, 45. Stable transfection of cells is typically achieved by integration of multiple copies of input DNA into host chromosomes 46. Indeed, such integrants typically represent up to 80% of all clones selected during HAC formation 2, 4, 6, 16, 22, 27–31.

Figure 6.

Mechanism of de novo HAC formation in human cells from the input DNA. Input DNA contains ~40 kb of alphoid DNA and ~10 kb vector DNA. Full lines represent input alphoid DNA. Multiple molecules of input DNA penetrate into a single human cell. Red arrows indicate to randomly introduced DSBs in input DNA during or after penetration into a human cell. The ends of input DNA molecules are underwent degradation. Degradation of either alphoid DNA or vector sequence takes place. The resulting fragments are assembled by either NHEJ or homologous recombination into long contig. The final linear concatamers either are circularized by NHEJ to form a HAC or are inserted into a host chromosome. In the latter case, the dicentric chromosome underwent breakage in a subsequent mitosis, with further breakage and circularization events leading to the HAC.

We suggest that during transfection, multiple alphoidtetO vector molecules penetrate some of the target cells. One or more double strand breaks (DSBs) are then randomly introduced into both input alphoid and vector sequences on the transfected molecules. The resulting linear molecules are subsequently modified in a range of different ways. For example, alphoidtetO and vector sequences may undergo different degrees of exonucleolytic degradation. In addition, recombination between inter- and intra-molecular alphoidtetO sequences generates products in which the alphoid DNA is either amplified or deleted. Next, linear extrachromosomal fragments are randomly joined together by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) to form concatamers consisting of direct and inverted copies (head-to-tail, head-to-head, and tail-to-tail) of rearranged input DNA. Selection for large size oligomers during HAC formation (between 1–5 Mb for the HACs analyzed so far) is presumably due to the fact that some minimal size of alphoid DNA array is required for de novo assembly of a functional kinetochore and its stable maintenance during subsequent cell divisions 47. The resulting linear concatamers may be either circularized or inserted into a host chromosome. In case of the alphoidtetO-HAC, a concatamer inserted into q arm of chromosome 13 near the KLHL1/ ATXN8OS locus. The targeted locus was next either excised from the chromosome, possibly by homologous recombination or the dicentric chromosome underwent breakage in a subsequent mitosis, with further breakage and circularization events leading to the observed HAC. However we do not think that the “chromosome integration” is the obligatory step for de novo HAC formation from all alphoid DNA arrays. The efficiency of HAC formation with alphoidtetO-DNA array is ~5 times lower than that observed with native alpha-satellite arrays isolated from human chromosomes 34 suggesting that assembly of functional kinetochores on this synthetic array is less efficient. Therefore the integration of a concatamer into a chromosome may occur if mature kinetochore is not formed on an array before the first cell division. For more competent alphoid arrays, the concatamer may be simply circularized by NHEJ to form a HAC. Analogous processes have also been shown to occur during chromosomal DSB repair 48–50, suggesting that HAC formation and chromosomal DSB repair are mediated by the same cellular machinery.

If HACs are to be used as vectors, their physical characterization is important to confirm their structural integrity during different manipulations, e.g., after the targeting of its kinetochore by different proteins fused with tetracycline repressor, after gene loading into the HAC using Cre-recombinase, or during the HAC transfer into different host cells. All of these manipulations have the potential to be mutagenic. For example, it was reported that the MMCT procedure induces rearrangements in HAC structure 33 that may in turn affect HAC stability or expression of genes that it carries. To evaluate the risk of the alphoidtetO-HAC rearrangements, we checked the integrity of the alphoidtetO-HAC after its transfer from CHO into human HT1080 cells. Eight independently obtained HT1080 clones were checked by Southern blot-hybridization. Indeed, the HAC was rearranged in two of these clones (~25%) (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Thus, once established, the alphoidtetO-HAC remains relatively structurally stable during propagation in host cells, however this must be confirmed at each stage of manipulation. This is consistent with previous analyses of the behavior of human chromosomes in different cell hosts 51.

To summarize, the alphoidtetO-HAC is the first de novo formed HAC centromere to be structurally analyzed in detail. The specific pattern of its SpeI-fragments may be used as indicator for HAC integrity during different manipulations. The features of the alphoidtetO-HAC are consistent with its broad use in synthetic biology experiments.

METHODS

Cell Cultures

HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Sigma, St Louis, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biowest, Nuaille, France) with 4 µg/ml of Blasticidin S (Bsr) (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C in 5% CO2. The hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT)-deficient Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (JCRB0218) were maintained in Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture (Invitrogen, USA) plus 10% FBS with 8 µg/ml of Bsr (Funakoshi, Japan). Chicken DT40 cells were maintained in the Bsr-containing RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% chicken serum and 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol at 37°C.

Southern-Blot Hybridization Analysis

Southern-blot hybridization was performed with a 32P-labelled probe. Genomic DNA was prepared in agarose plugs and restriction-digested either by SpeI or PmeI or PacI in the buffer recommended by the enzyme supplier. The digested DNA was CHEF separated, and blot-hybridized with either a 276-bp probe specific to a tetO-containing alphoid sequence or a 200-bp probe 1 or a 201-bp probe 3 specific to a vector part. DNA sequences of the probes were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Table 1. Blots were incubated for 2 h at 65°C in pre-hybridization Church’s buffer (0.5 M Na-phosphate buffer containing 7% SDS and 100 µg/ml of unlabelled salmon sperm carrier DNA). The labeled probe was heat denatured in boiling water for 5 min and snap cooled on ice. The probe was added to the hybridization buffer and allowed to hybridize overnight at 65°C. Blots were washed twice in 2× SSC (300 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 0.1% SDS for 30 min at room temperature, then three times in 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS for 30 min at 65°C. Blots were exposed to X-ray film for 24–72 h at −70°C.

Microcell-Mediated Chromosome Transfer

Microcell-mediated chromosome transfer (MMCT) was performed as described previously 35, 52,53.

PCR Analysis

Genomic DNA from HT1080 and DT40 cell lines was extracted using a genomic extraction kit (Gentra System, Minneapolis, MN, USA). PCR analysis was carried out using standard techniques. The primer pairs for detection of the direct and inverted alphoid DNA repeats are listed in Table 1.

FISH with PNA Probes

HT1080 cells containing the HAC were grown in DMEM medium to 70–80% confluence. Metaphase cells were obtained with addition of 1 mM of TN16 (Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA, USA) into culture and further incubation for 3 hours. Metaphase chromosomes were prepared with hypotonic solution as describe previously 54. About 20 µl of metaphase chromosome were evenly spread on the slide and let fixative solution evaporate gradually. Dry slides were rehydrated with 1xPBS for 4% formaldehyde fixation, followed by rinsing in 1xPBS and ethanol series dehydration. PNA (peptide nucleic acid) labeled probes used were telomere (CCCTAA)3-Cy3) (PerSeptive Biosystems, Inc., Framingham, MA, USA) and tetO-alphoid array (FITC-OO-ACCACTCCCTATCAG) (PANAGENE, South Korea). Twenty micrograms of PNA probes were mixed with hybridization buffer and applied to the sample, followed by denaturation at 80°C for 3 minutes. Slides were hybridized for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark room. The unspecific labeling was removed by series of washing in 70% formamide, 10mM Tris pH 7.2, 0.1% BSA and 1xTBS-T. Metaphase chromosomes were stained with DAPI in 2xSSC buffer. Slides were dehydrated gradually with series of ethanol and mounted with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen, USA). Images were capture using a Zeiss Microscope (Axiophot) equipped with a cooled-charge-couple device (CCD) camera (Cool SNAP HQ, Photometric) and analyzed by IP lab software (Signal Analytics). PNA-DNA hybrid demonstrates high hybridization efficiency, high staining intensity and exhibit more stable duplex form with complementary nucleic acid 55.

DNA Fiber-FISH by DNA Combing

DNA fiber-FISH was performed as previously described 56 with modifications. HT1080 ells with HAC were trypsinized, and resuspended in PBS. Cells were embedded in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis agarose plugs to prepare high-molecular-weight genomic DNA. After proteinase K digestion, agarose plugs were washed with TE, and then were melted in 100 mmol/L MES (pH 6.5). Agarose was digested with 2 µl of β-agarase (BioLabs, Lawrenceville, GA, USA). The DNA solution was poured into a Teflon reservoir and DNA was combed onto silanized coverslips (Microsurfaces, Inc., Austin, TX, USA) using a custom-made combing machine. Coverslips with combed DNA were baked 2 h at 60°C and ten were denatured in 0.5 N NaOH for 20 min. After washing with PBS, the DNA slides were dehydrated sequentially 70%, 90% and 100% ethanol. 20 µl of hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 2xSSC, 0.5% SDS, 0.5% sodium lauryl sarcosine, 1% blocking buffer, 10mM NaCl, 300 ng probe and 3 µg human cot-1) was added to each coverslip and incubate at 37 °C overnight in a wet chamber. Probes were labeled with BioPrime DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen, USA, 18094). After hybridization, slides were washed with 2xSSC, 50% formamide and 2xSSC at room temperature. Probes were detected with 3 layers of Alexa fluro 488 conjugated streptAvidin (Invitrogen, USA, S-32354) and 2 layers of biotinylated goat anti-streptavidin antibody (Vector, USA, BA-0500), namely, streptAvidin- anti-streptavidin antibody- streptAvidin- anti-streptavidin antibody-streptAvidin. The slides were scanned with BD pathway 855 controlled by AttoVision (Becton Dickinson). The length of probes and the length between probes were measured using ImageJ (from the National Cancer Institute) with custom-made modifications and were calculated with a constant of 2kb/micrometer. Fiber-FISH was also carried out using two differently labeled probes, i.e. RCA/SAT43 vector DNA and tetO-alphoid DNA.

Rescue of the HAC Fragments by in vivo Recombination in Yeast

For transformations, the highly transformable Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain VL6–48 (MATα, his3-Δ200, trp1-Δ1, ura3-52, lys2, ade2-101, met14) that has HIS3 deleted was used. A 262 bp linker-fragment homologous to the vector sequence (Table 1) was designed. Approximately 1 µg of genomic DNA was prepared from DT40 cells carrying the HAC, digested by SpeI and co-transformed along with the 1 µg of linker-fragment into yeast shperoplasts. Yeast transformation experiments were carried out as described previously 42.

Characterization of the TAR-Rescued Molecules

The YAC/BACs were moved to Escherichia coli by electroporation as previously described 42 and references therein. In brief, yeast chromosome-size DNAs were prepared in agarose plugs and, after melting and agarase treatment, the DNAs were electroporated into DH10B competent cells (Gibco/BRL, USA) by using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser. To check the size of inserts in the BAC clones, the BAC clones were grown at 30°C to prevent alphoid DNA instability in bacterial cells, DNA was digested with SpeI, separated by clamped homogeneous electrical field electrophoresis (CHEF), and stained with EtBr.

ChIP Assay and Real-Time PCR

ChIP with antibodies against CENP-A (mAN1), dimethyl histone H3 Lys4 (Upstate), trimethyl H3 Lys4 (Upstate USA, Charlottesville, VA, USA), trimethyl H3 Lys9 (Upstate) was carried out according to a previously described method 36. Briefly, cultured cells were cross-linked in 0.5% formaldehyde for 5 min at 22°C. After addition of 0.2 vol. of 2.5 M glycine and incubation for 5 min, fixed cells were washed with TBS buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl, 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, pH 7.4) twice and washed once with sonication buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1.5 µM aprotinin, 10 µM leupeptin, 1 mM DTT, and 40 µM MG132). Next, cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Soluble chromatin was prepared by sonication (Bioruptor sonicator; Cosmo Bio) to an average DNA size of 0.5 kb in sonication buffer and immnnoprecipitated in IP buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 600 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.05% SDS, 1.0% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol, 1.5 µM aprotinin, 10 µM leupeptin, 1 mM DTT, and 40 µM MG132). Protein G sepharose (Amersham, USA) blocked with BSA was added, and the antibody–chromatin complex was recovered by centrifugation. The recovery ratio of the immunoprecipitated DNA relative to input DNA was measured by real-time PCR using a CFX96 realtime PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, USA) and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA). Primers 5SDNA-F1 and 5SDNA-R1 for 5S ribosomal DNA, 11-10R and mCbox-4 for 11-mer of chromosome 21 alphoid DNA, Sat2-F1 and Sat2-R1 for pericentromeric satellite 2 repeat (8) tet-1 and tet-3 for the alphoidtetO DNA, and bsr-F and bsr-R for the marker gene (bsr) of the alphoidtetO-HAC were described previously 34.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, USA (VL), the Wellcome Trust and The Darwin Trust of Edinburgh (WCE), 21st Century COE program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MO), the Grand-in-Aid for Scientific Research from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MO and HM) and the Kazusa DNA Research Institute Foundation (HM).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to design of the research; N.K., A.S., I.E., H.F., M.N., Y.I., H.S.L. performed experiments; N.K. and V.L. contributed to writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ren X, Tahimic CG, Katoh M, Kurimasa A, Inoue T, Oshimura M. Human artificial chromosome vectors meet stem cells: new prospects for gene delivery. Stem Cell Review. 2006;2:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s12015-006-0008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimes BR, Monaco ZL. Artificial and engineered chromosomes: Developments and prospects for gene therapy. Chromosoma. 2005;114:230–241. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu J, Willard HF. Artificial and engineered chromosomes: Non-integrating vectors for gene therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2005;11:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monaco ZL, Moralli D. Progress in artificial chromosome technology. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:324–327. doi: 10.1042/BST20060324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macnab S, Whitehouse A. Progress and prospects: human artificial chromosomes. Gene Ther. 2009;16:1180–1188. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazuki Y, Oshimura M. Human artificial chromosomes for gene delivery and the development of animal models. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:1591–15601. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills W, Critcher R, Lee C, Farr CJ. Generation of an approximately 2.4 Mb human X centromere-based minichromosome by targeted telomere-associated chromosome fragmentation in DT40. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:751–761. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen MH, Mee PJ, Nichols J, Yang J, Brook F, Gardner RL, Smith AG, Brown WR. A structurally defined mini-chromosome vector for the mouse germ line. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)00261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang JW, Pendon C, Yang J, Haywood N, Chand A, Brown WR. Human mini-chromosomes with minimal centromeres. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1891–1902. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.12.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spence JM, Critcher R, Ebersole TA, Valdivia MM, Earnshaw WC, Fukagawa T, Farr CJ. Co-localization of centromere activity, proteins and topoisomerase II within a subdomain of the major human X alpha-satellite array. EMBO J. 2002;21:5269–5280. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auriche C, Carpani D, Conese M, Caci E, Zegarra-Moran O, Donini P, et al. Functional human CFTR produced by a stable minichromosome. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:862–868. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katoh M, Ayabe F, Norikane S, Okada T, Masumoto H, Horike S, Shirayoshi Y, Oshimura M. Construction of a novel human artificial chromosome vector for gene delivery. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazuki Y, Hoshiya H, Takiguchi M, Abe S, Iida Y, Osaki M, Katoh M, Hiratsuka M, Shirayoshi Y, Hiramatsu K, Ueno E, Kajitani N, Yoshino T, Kazuki K, Ishihara C, Takehara S, Tsuji S, Ejima F, Toyoda A, Sakaki Y, Larionov V, Kouprina N, Oshimura M. Refined human artificial chromosome vectors for gene therapy and animal transgenesis. Gene Ther. 2010;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington JJ, Van Bokkelen G, Mays RW, Gustashaw K, Willard HF. Formation of de novo centromeres and construction of first-generation human artificial microchromosomes. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:345–355. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeno M, Grimes B, Okazaki T, Nakano M, Saitoh K, Hoshino H, McGill NI, Cooke H, Masumoto H. Construction of YAC-based mammalian artificial chromosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:431–439. doi: 10.1038/nbt0598-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimes BR, Schindelhauer D, McGill NI, Ross A, Ebersole TA, Cooke HJ. Stable gene expression from a mammalian artificial chromosome. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:910–914. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mejía JE, Alazami A, Willmott A, Marschall P, Levy E, Earnshaw WC, Larin Z. Efficiency of de novo centromere formation in human artificial chromosomes. Genomics. 2002;79:297–304. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kouprina N, Ebersole T, Koriabine M, Pak E, Rogozin IB, Katoh M, Oshimura M, Ogi K, Peredelchuk M, Solomon G, Brown W, Barrett JC, Larionov V. Cloning of human centromeres by transformation-associated recombination in yeast and generation of functional human artificial chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:922–934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basu J, Stromberg G, Compitello G, Willard HF, Van Bokkelen G. Rapid creation of BAC-based human artificial chromosome vectors by transposition with synthetic alpha-satellite arrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:587–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu J, Compitello G, Stromberg G, Willard HF, Van Bokkelen G. Efficient assembly of de novo human artificial chromosomes from large genomic loci. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebersole TA, Ross A, Clark E, McGill N, Schindelhauer D, Cooke H, Grimes B. Mammalian artificial chromosome formation from circular alphoid input DNA does not require telomere repeats. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1623–1631. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.11.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moralli D, Simpson KM, Wade-Martins R, Monaco ZL. A novel human artificial chromosome gene expression system using herpes simplex virus type 1 vectors. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:911–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki N, Nishii K, Okazaki T, Ikeno M. Human artificial chromosomes constructed using the bottom-up strategy are stably maintained in mitosis and efficiently transmissible to progeny mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:26615–26623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamoto Y, Nakano M, Ohzeki J, Larionov V, Masumoto H. A minimal CENP-A core is required for nucleation and maintenance of a functional human centromere. EMBO J. 2007;26:1279–1291. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazuki Y, Hoshiya H, Takiguchi M, Abe S, Iida Y, Osaki M, Katoh M, Hiratsuka M, Shirayoshi Y, Hiramatsu K, Ueno E, Kajitani N, Yoshino T, Kazuki K, Ishihara C, Takehara S, Tsuji S, Ejima F, Toyoda A, Sakaki Y, Larionov V, Kouprina N, Oshimura M. Refined human artificial chromosome vectors for gene therapy and animal transgenesis. Gene Ther. 2011;18:384–393. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazuki Y, Hiratsuka M, Takiguchi M, Osaki M, Kajitani N, Hoshiya H, Hiramatsu K, Yoshino T, Kazuki K, Ishihara C, Takehara S, Higaki K, Nakagawa M, Takahashi K, Yamanaka S, Oshimura M. Complete genetic correction of ips cells from Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:386–393. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mejia JE, Willmott A, Levy E, Earnshaw WC, Larin Z. Functional complementation of a genetic deficiency with human artificial chromosomes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:315–326. doi: 10.1086/321977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotzamanis G, Cheung W, Abdulrazzak H, Perez-Luz S, Howe S, Cooke H, et al. Construction of human artificial chromosome vectors by recombineering. Gene. 2005;351:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breman AM, Steiner CM, Slee RB, Grimes BR. Input DNA ratio determines copy number of the 33 kb Factor IX gene on de novo human artificial chromosomes. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:315–323. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocchi L, Braz C, Cattani S, Ramalho A, Christan S, Edlinger M, Braz C, Cattani S, Ramalho A, Christan S, Edlinger M, Ascenzioni F, Laner A, Kraner S, Amaral M, Schindelhauer D. Escherichia coli-cloned CFTR loci relevant for human artificial chromosome therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010;21:1077–1092. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki N, Itou T, Hasegawa Y, Okazaki T, Ikeno M. Cell to cell transfer of the chromatin-packaged human beta-globin gene cluster. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alazami AM, Mejía JE, Monaco ZL. Human artificial chromosomes containing chromosome 17 alphoid DNA maintain an active centromere in murine cells but are not stable. Genomics. 2004;835:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moralli D, Chan DY, Jefferson A, Volpi EV, Monaco ZL. HAC stability in murine cells is influenced by nuclear localization and chromatin organization. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakano M, Cardinale S, Noskov VN, Gassmann R, Vagnarelli P, Kandels-Lewis S, Larionov V, Earnshaw WC, Masumoto H. Inactivation of a human kinetochore by specific targeting of chromatin modifiers. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iida Y, Kim JH, Kazuki Y, Hoshiya H, Takiguchi M, Hayashi M, Erliandri I, Lee HS, Samoshkin A, Masumoto H, Earnshaw WC, Kouprina N, Larionov V, Oshimura M. Human artificial chromosome with a conditional centromere for gene delivery and gene expression. DNA Res. 2010;17:293–301. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JH, Kononenko A, Erliandri I, Kim TA, Nakano M, Iida Y, Barrett JC, Oshimura M, Masumoto H, Earnshaw WC, Larionov V, Kouprina N. Human artificial chromosome (HAC) vector with a conditional centromere for correction of genetic deficiencies in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:20048–20053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114483108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cardinale S, Bergmann JH, Kelly D, Nakano M, Valdivia MM, Kimura H, Masumoto H, Larionov V, Earnshaw WC. Hierarchical inactivation of a synthetic human kinetochore by a chromatin modifier. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:4194–4204. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergmann JH, Rodríguez MG, Martins NM, Kimura H, Kelly DA, Masumoto H, Larionov V, Jansen LE, Earnshaw WC. Epigenetic engineering shows H3K4me2 is required for HJURP targeting and CENP-A assembly on a synthetic human kinetochore. EMBO J. 2011;30:328–340. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergmann JH, Jakubsche JN, Martins NM, Kagansky A, Nakano M, Kimura H, Kelly DA, Turner BM, Masumoto H, Larionov V, Earnshaw WC. Epigenetic engineering: histone H3K9 acetylation is compatible with kinetochore structure and function. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:411–421. doi: 10.1242/jcs.090639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebersole T, Okamoto Y, Noskov VN, Kouprina N, Kim JH, Leem SH, Barrett JC, Masumoto H, Larionov V. Rapid generation of long synthetic tandem repeats and its application for analysis in human artificial chromosome formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e130. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kouprina N, Larionov V. Innovation - TAR cloning: insights into gene function, long-range haplotypes and genome structure and evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2006;7:805–812. doi: 10.1038/nrg1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kouprina N, Larionov V. Selective isolation of genomic loci from complex genomes by transformation-associated recombination cloning in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature Protocols. 2008;3:371–377. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larionov V, Kouprina N, Eldarov M, Perkins E, Porter G, Resnick MA. Transformation-associated recombination between diverged and homologous DNA repeats is induced by strand breaks. Yeast. 1994;10:93–104. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calos MP, Lebkowski JS, Botchan MR. High mutation frequency in DNA transfected into mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1983;80:3015–3019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.10.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wake CT, Gudewicz T, Porter T, White A, Wilson JH. How damaged is the biologically active subpopulation of transfected DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1984;4:387–398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janicki SM, Tsukamoto T, Salghetti SE, Tansey WP, Sachidanandam R, Prasanth KV, Ried T, Shav-Tal Y, Bertrand E, Singer RH, Spector DL. From silencing to gene expression: real-time analysis in single cells. Cell. 2004;116:683–698. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spence JM, Mills W, Mann K, Huxley C, Farr CJ. Increased missegregation and chromosome loss with decreasing chromosome size in vertebrate cells. Chromosoma. 2006;115:60–74. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Critchlow SE, Jackson SP. DNA end-joining: from yeast to man. TIBS. 1988;23:394–398. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dellaire G, Yan J, Little KC, Drouin R, Chartrand P. Evidence that extrachromosomal double-strand break repair can be coupled to the repair of chromosomal double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Chromosoma. 2002;111:304–312. doi: 10.1007/s00412-002-0212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Würtele H, Little KC, Chartrand P. Illegitimate DNA integration in mammalian cells. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1791–1799. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meaburn KJ, Parris CN, Bridger JM. The manipulation of chromosomes by mankind: the uses of microcell-mediated chromosome transfer. Chromosoma. 2005;114:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oshimura M, Katoh M. Transfer of human artificial chromosome vectors into stem cells. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2008;16:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fournier RE, Ruddle FH. Microcell-mediated transfer of murine chromosomes into mouse, Chinese hamster, and human somatic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:319–323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.1.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henegariu O, Heerema NA, Wright LL, Bray-ward P, Ward DC, Vance GH. Improvement of cytogenetic slide preparation: controlled chromosome spreading, chemical aging and gradual denaturing. Cytometry. 2001;43:101–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lansdorp PM, Verwoerd NP, van de Rijke FM, Dragowska V, Little MT, Dirks RW, Raap AK, Tanke HJ. Heterogeneity in telomere length of human chromosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:685–691. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conti C, Herrick J, Bensimon A. Unscheduled DNA replication origin activation at inserted HPV 18 sequences in a HPV-18/MYC amplicon. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:724–734. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.