Abstract

Mammary gland development is a multistage process requiring tightly regulated spatial and temporal signalling pathways. Many of these pathways have been shown to be sensitive to oxidative stress. Understanding that the loss of manganese superoxide dismutase (Sod2) leads to increased cellular oxidative stress, and that the loss or silencing of this enzyme has been implicated in numerous pathologies including those of the mammary gland, we sought to examine the role of Sod2 in mammary gland development and function in situ in the mouse mammary gland. Using Cre-recombination driven by the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter, we created a mammary-specific post-natal conditional Sod2 knock-out mouse model. Surprisingly, while substantial decreases in Sod2 were noted throughout both virgin and lactating adult mammary glands, no significant changes in developmental structures either pre- or post-pregnancy were observed histologically. Moreover, mothers lacking mammary gland expression of Sod2 were able to sustain equal numbers of litters, equal pups per litter, and equal pup weights as were control animals. Overall, our results demonstrate that loss of Sod2 expression is not universally toxic to all cell types and that excess mitochondrial superoxide can apparently be tolerated during the development and function of post-natal mammary glands.

Keywords: mouse mammary tumor virus, breast, mouse, reactive oxygen species, milk

Introduction

Mammalian mammary glands are derived from the ventral ectoderm, and development of these organs occurs in four distinct stages: embryonic, neonatal, pubertal, and reproductive [1,2]. In fully differentiated virgin mammary glands, epithelial cells line the lumens of ductal structures while myoepithelial cells surround these arrangements [3]. During lactation, milk producing alveoli derive from the epithelial ductal cells, thus creating a third major cell type within the mammary gland [3]. Each stage of development is characterised by complex and highly regulated signalling pathways (e.g. Jak/Stat, estrogen signalling, Jnk/Erk, etc.) required for proper development [4,5]. Interestingly, many of the proteins and transcription factors necessary for mammary gland development have demonstrated differential sensitivity to oxidative stress [6–9]. Furthermore, various studies have verified the effects of increased oxidative stress on fully differentiated mammary tissue and mammary carcinoma [10,11]. In contrast, while exhaustive in vitro examinations have shown reactive oxygen species (ROS) may induce aberrant protein and transcription factor signalling in various adult mammary tissue models [12–14], limited in situ data have demonstrated the role of oxidative stress in the mammalian mammary gland through its full developmental cycle.

Due to the respiratory function of the mitochondria during aerobic metabolism, this organelle serves as a major source of ROS in eukaryotic cells [15]. Additionally, non-pathologic mammary glands are rarely hypoxic, and primarily rely upon aerobic metabolism for ATP production [16]. Normally, the mitochondrially located antioxidant enzyme manganese superoxide dismutase (Sod2) maintains a nominal steady-state level of super-oxide [17]. The loss or silencing of Sod2 has demonstrated increased cellular oxidative stress, developmental aberrations, and exacerbated carcinogenesis in various experimental models [18–22]. With this understanding, it is hypothesised that Sod2 plays a critical role in the development and function of normal mammalian mammary tissue. To date, only one study has demonstrated aberrant embryonic development of the mammary gland in the absence of Sod2 [23]. Using murine Sod2 deficient mammary anlagen implanted into the renal capsule of recipient mice, it was determined that the absence of Sod2 caused decreased E-cadherin expression, increased Ki-67 labelling, and hyperplasia of the explanted mammary gland. While these results confirm Sod2 dependence in embryonic mammary development, the role of Sod2 in later stages of development remains unclear. To address these deficits in our knowledge, we employed a mammary-specific Sod2 conditional knock-out mouse to examine the effects of increased oxidative stress in post-natal mammary gland growth and function.

Methods

Mice and characterisation

Mice homozygous for the floxed Sod2 allele (i.e. B6.Cg-Sod2tm1, shorthand Sod2L/L), in which exon 3 of the Sod2 gene is flanked by 2 loxP sequences, have been previously described [24]. B6129-Tg(MMTV-cre)4Mam/J or MMTV-Cre mice (cre-recombinase is exogenously expressed under control of the mouse mammary tumour virus (MMTV) LTR where Cre-recombinase expression is primarily limited to mammary epithelial cells in virgin and lactating mice) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, and have been previously described [25]. To obtain conditional mammary Sod2 homozygous knock-out animals (i.e. Sod2−/−), parent strains of both the floxed Sod2 and MMTV-Cre mice were bred to the F2 generation. MMTV-Cre was only passed through male parents to limit non-specific oocyte expression. Due to the variability in strains, littermate floxed animals (i.e. Sod2L/L) served as controls. Genotyping, real-time quantitative RT-PCR, and western blotting were performed as previously described [18,26]. Oligonucleotides used for real-time quantitative RT-PCR are as follows: Forward Sod2: GCTCTGGCCAAGGGAGATGT; Reverse Sod2: GGGCTCAGGTTTGTCCAGAAA; Forward 18s: GCCCGAAGCGTTTACTTTGA; Reverse 18s: TCATGGCCTCAGTTCCGAA; Forward Sod1: AATGTGACTGCTGGAAAGGACG; Reverse Sod1: GACCACCATTGTACGGCCAA; Forward Cat: GCTCAGCCCTGGAGCACAG; Reverse Cat: CTTTGTGTAGAATGTCCGCACCT; Forward Gpx1: TTTCCCGTGCAATCAGTTC; Reverse Gpx1: TCGGACGTACTTGAGGGAAT. Antibodies used are as follows: Sod2 (Catalog #06-984, Millipore, USA), Beta-actin (Catalog #E7, University of Iowa Hybridoma Core, Iowa City, IA), and 8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine (Catalog #MAB6116, Abnova, Walnut, CA). For all experiments, fresh tissue was harvested and used from female animals at 8–10 weeks of age, unless otherwise noted. All work was performed under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa.

Mammary whole mounts and histology

For whole mounts, inguinal mammary glands were excised from virgin mice and fixed overnight on glass slides in 75% EtOH + 25% Acetic Anhydride (v/v). Following this, slides were placed in 70% EtOH followed by distilled water, and then allowed to incubate in haematoxylin (SigmaPath) until fully stained. Whole mounts were cleared using acid alcohol (0.25% HCl in EtOH), and blued using lithium carbonate (1.36%). Finally, slides were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of EtOH, cleared using xylenes, and stored in light mineral oil for long-term storage. For histology, tissues were fixed in 10% neutral formalin, then processed and embedded in paraffin. Four- to five-micrometer sections were prepared with a microtome (HM 355, Microm, Walldorf, Germany) and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) with an automated slide stainer (Sakura DRS 601 Diversified Stainer, Sakura, Hayward, CA). Stained slides were mounted with Solvent 100 mounting media, and brightfield micrographs of stained sections were taken with a microscope (Olympus BX-51, Olympus, Melville, NY) fitted with an Olympus DP70 camera (Olympus).

8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine immunohistochemistry

Mouse mammary tissues were sectioned (4 μm) and hydrated through a series of ethanol and xylene baths. Antigen retrieval was performed with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a commercial heat-induced epitope unit according to manufacturer’s instructions (125°C × 5 minutes, Decloaker Chamber™ NxGen, Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide (8 minutes). Non-specific antibody binding Fc receptors (60 minutes × 10% solution, HB-197™, American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA, USA) and general tissue blocking (60 minutes, Background Buster, Innovex Biosciences, Richmond, CA) were performed to prevent background staining. Primary mouse monoclonal anti-8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine was applied (1:100 × 60 minutes) and after washes, a secondary Ab kit was applied according to manufacturer’s instructions (Dako Mouse Envision, Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Slides were counterstained in hematoxylin (1 minutes), blued in Scott’s tap water and routinely dehydrated through serial ethanol and xylene baths and coverslipped.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. All experiments were performed using 3 mice per group unless otherwise stated. For most experiments, comparisons between groups were analysed by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t-test. A p-value of less than 0.01 was considered to be significant.

Results

Sod2 is conditionally deleted in virgin and lactating mammary glands

We and others have demonstrated the conditional Sod2 knock-out mouse to be a viable model of increased oxidative stress in vivo [18,27,28]. To understand the effects of increased oxidative stress on post-natal mammary gland development, we created a conditional mammary Sod2 knock-out mouse using Cre-recombination driven under the control of the MMTV promoter. The MMTV promoter becomes activated shortly after birth (neonatal developmental stage), and has been demonstrated to be highly expressed in epithelial and myoepithelial cells in both virgin and lactating mammary glands with little or no expression in stroma, fibroblasts, or adipocytes [29], making it a never before utilised model for studying Sod2 loss in multiple cell types and stages of mammary gland development.

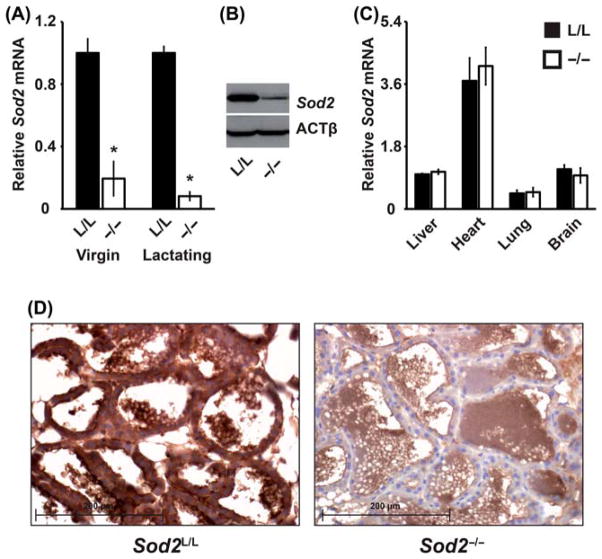

After breeding mice to the F2 generation, PCR analysis of tail sample DNA was used to confirm the proper genotype of animals (data not shown). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis demonstrated an approximate 90% decrease in Sod2 mRNA in mammary glands from both Sod2−/− virgin and lactating mice compared to their Sod2L/L littermate controls (Figure 1A). This loss of Sod2 was also seen at the protein level as revealed by both western blot and immunohistochemical analysis in lactating mammary glands (Figure 1B, D). No off-target tissues queried demonstrated any significant decreases in Sod2 mRNA (Figure 1C) supporting previous findings using MMTV driven Cre-recombination [25]. Overall, the MMTV driven Cre-recombinase-mediated excision of Sod2 provides an optimal model for studying the role of this anti-oxidant enzyme in post-natal mammary gland development and function.

Figure 1.

Sod2 is conditionally and effectively removed from virgin and lactating mammary tissue. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of Sod2 mRNA extracted from 8 to 10-week old Sod2L/L (L/L) or Sod2−/− (−/−) virgin or lactating mammary glands. Results normalised first to 18s mRNA then to respective Sod2L/L by the ddCT method. (B) Western blot analysis of Sod2 protein in 8–10-week old Sod2L/L or Sod2−/− lactating mammary glands. Beta-actin (ACTβ) is shown as a control for loading and transfer. (C) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of Sod2 mRNA extracted from 8 to 10-week old Sod2L/L (L/L) or Sod2−/− (−/−) tissues. Results normalised first to 18s mRNA then to Sod2L/L liver by the ddCT method. (D) Immunohistological analysis of Sod2 protein in 8–10-week old Sod2 L/L or Sod2−/− lactating mammary glands. Brown stain indicates Sod2 immunoreactivity; blue indicates nuclear counterstain. Three mice per experiment were analysed; data are shown as mean and s.d. Where applicable, * = p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test versus Sod2L/L.

Increased oxidative stress does not alter other major antioxidant enzymes

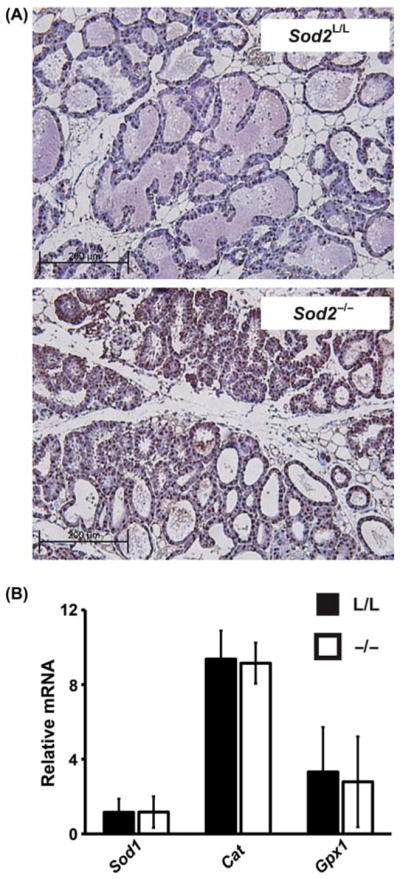

To assess the level of oxidative stress in Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− mammary glands, immunohistochemical staining for 8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine was performed on lactating mammary gland tissue. Significant increases in 8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine staining are noted in the Sod2−/− mammary glands when compared to Sod2L/L controls (Figure 2A), thus confirming increased cellular oxidative stress due to the loss of Sod2. We additionally performed immunohistochemical analysis for 3-nitrotyrosine, but levels were undetectable in Sod2L/L or Sod2−/− mammary glands. This finding of undetectable levels of 3-nitrotyrosine is consistent with previous findings using the Sod2 conditional mouse [18]. Furthermore, it would be hypothesised that this cellular oxidative stress may elicit compensatory changes in other major cellular antioxidant enzymes. To address this, quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed for Cu/Zn SOD (Sod1), catalase (Cat), and glutathione peroxidase 1 (Gpx1; Figure 2B). Surprisingly, no significant changes were noted in any of the antioxidant enzyme mRNA levels suggesting other mechanisms for adaptation to increased oxidative stress may be in effect.

Figure 2.

Oxidative stress increases have no effect on major antioxidant enzymes. (A) Immunohistological analysis of 8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine in 8–10-week old Sod2L/L or Sod2−/− lactating mammary glands. Brown stain indicates 8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine immunoreactivity; blue indicates nuclear counterstain. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of Sod1, Cat, and Gpx1 mRNA extracted from 8 to 10-week old Sod2L/L (L/L) or Sod2−/− (−/−) lactating mammary glands. Results normalised first to 18s mRNA then to Sod2L/L Sod1 mRNA by the ddCT method.

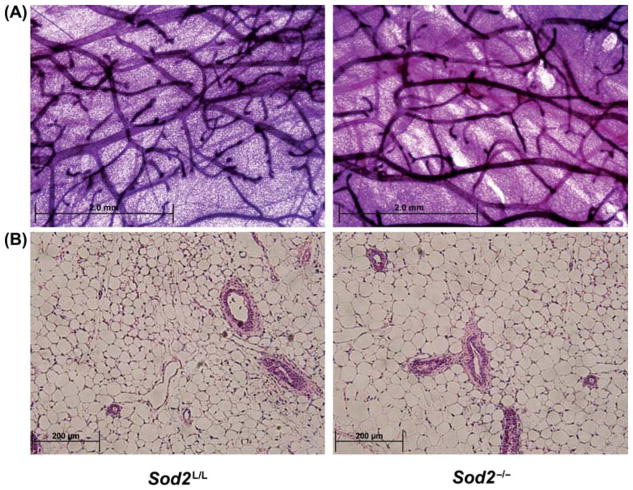

The loss of Sod2 has no apparent effect on post-natal mammary development

To understand the consequence of Sod2 loss in mammary development, whole mounts of 8–10 week old virgin mammary glands were prepared (Figure 3A). No significant differences were noted between Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− whole mounts, as similar quantities and qualities of ducts, branches and buds were observed in both groups. Histological analysis of virgin mammary glands also demonstrated no notable differences, as the number, size and quality of mammary epithelial structures were not significantly changed in Sod2−/− versus Sod2L/L (Figure 3B). Taken together, the data suggest that Sod2 does not play a significant role in the development of pubertal mammary gland structures.

Figure 3.

The loss of Sod2 has no apparent effect on virgin mammary development. (A) Low magnification (4×) of hematoxylin stained 10-week old Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− whole mounted virgin mammary glands. (B) High magnification (40×) of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained 10-week old Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− virgin mammary glands. Images reviewed by pathologist demonstrate no significant changes.

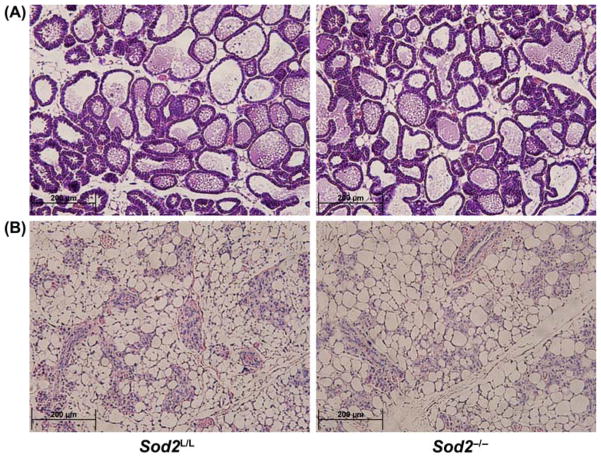

While Sod2 loss did not hinder pubertal mammary development, the role of Sod2 in the reproductive cycle of the mammary gland remained unknown. To address this, Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− female mice were mated with wild-type C57BL/6 males to induce mammary development and lactogenic differentiation. Seven days after birth (during peak lactation), mammary glands were extracted from the females and histologically analysed. Interestingly, no differences were observed between Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− lactating mammary glands as both demonstrated similar numbers and structures of differentiated ductal structures as well as colloidal material within the ducts (Figure 4A). Finally, mammary glands were extracted 14 days after weaning of the mice to assess differences during involution. Similar to the previous stages of development, no significant differences were noted in the involuted mammary glands in the presence or absence of Sod2 (Figure 4B). Taken together, these data imply that Sod2 plays a minimal role in many or most stages of post-natal mammary gland development.

Figure 4.

Reproductive stages of mammary gland development including proliferation, lobuloalveolar differentiation, and lactation are apparently unaffected by Sod2 loss. (A) High magnification (40×) of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained 7-day postpartum Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− lactating mammary glands. (B) High magnification (40×) of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained involuted Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− mammary glands. Images reviewed by pathologist demonstrate no significant changes.

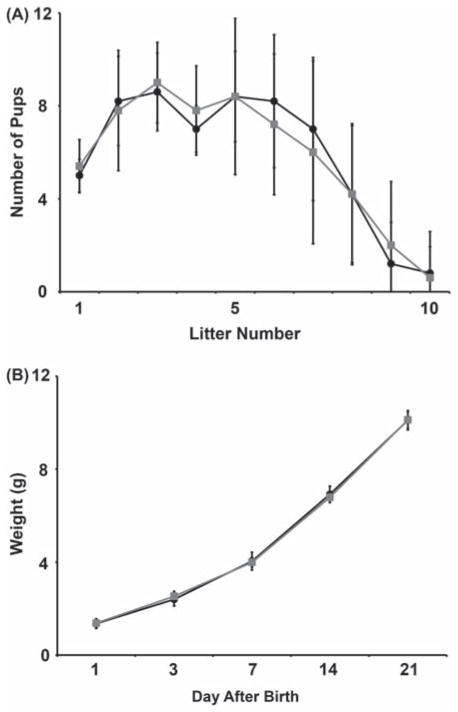

Sod2 deficient mice lactate normally and sustain healthy litters

While the physical structures comprising the mammary glands were shown to be unaffected by the loss of Sod2, the question still remained as to the functionality of the glands. To address this, Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− females were allowed to breed repetitively to assess the number of litters each group could sustain throughout their reproductive lifetime. Both Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− mothers were able to sustain equal numbers of pups per litter (Figure 5A) as well as a similar numbers of total litters (Sod2L/L average = 8.4 ± 1.1 litters, Sod2−/− average = 8.0 ± 1.6 litters, p = 0.82). In addition, the pups weights were unaffected by the loss of Sod2 in the lactating mothers, suggesting the production of normal milk quantity and quality (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Conditional mammary Sod2 knock-out mothers bear normal numbers of healthy pups and sustain multiple litters. (A) Average counts of number of pups per litter throughout reproductive lifetime in Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− mice. Black bar = Sod2L/L, Grey bar = Sod2−/−. (B) Average weight per pup at varying time points until weaning. Black bar = Sod2L/L, Grey bar = Sod2−/−. Six mice per experiment were analysed; data are shown as mean and s.d.

It was hypothesised that after repetitive cycles of lactation and involution that a small population of cells may have escaped Sod2 excision by poor Cre-recombinase penetrance and these cells may have selectively out-competed Sod2−/− cells during the proliferation of the reproductive mammary gland. To address this, we performed quantitative real-time PCR analysis on lactating mammary glands from Sod2L/L and Sod2−/− females as a function of the numbers of litters they bore. It was determined that Sod2 expression did in fact remain low regardless of litter number (Table I), indicating that the repopulation following involution was likely not accomplished by a stem cell compartment escaping Sod2 excision. In summary, the data presented here strongly support a negligible role for Sod2 in the normal development and function of murine mammary glands.

Table I.

Sod2 knock-out remains penetrant throughout multiple litters.

| Litter | Sod2L/L | Sod2−/− |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.01 ± 0.14 | 0.08 ± 0.01* |

| 2 | 0.98 ± 0.15 | 0.05 ± 0.02* |

| 3 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.09 ± 0.02* |

| 4 | 1.03 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.03* |

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of Sod2 mRNA extracted from Sod2L/L or Sod2−/− lactating mammary glands after respective litter number. Results normalised first to 18s mRNA then to respective Sod2L/L by the ddCT method. Three mice per experiment were analysed; data are shown as mean and s.d. Where applicable, * = p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test versus Sod2L/L.

Discussion and conclusions

The results presented here demonstrate that normal mouse mammary gland development and function are minimally affected by the loss of Sod2. These results directly contrast with numerous reports of other organs systems that are highly dependent upon Sod2 for proper development and survival. For example, the constitutive Sod2 knock-out mouse is lethal shortly after birth due to severe systemic oxygen toxicity [21,22]. Furthermore, using the Sod2 conditional knock-out mouse we and others have shown specific developmental aberrations to the loss of Sod2 in tissues such as liver, muscle, neurons, and immune cells [18,27,28,30]. While we were unable to identify any compensatory up-regulation of other antioxidant enzymes (i.e. Sod1, Cat, Gpx1) in the Sod2−/− mammary tissue, further examination is warranted in the elucidation of how this organ system is resistant to the effects of increased oxidative stress.

The use of MMTV-Cre recombination has been used extensively in the illumination of gene function necessary for normal mammary gland development and function [31–35]. While MMTV-Cre is presumably the best current model to study the effects of post-natal mammary growth, limitations exist within the model that may hinder the interpretation of results. MMTV-Cre recombination has been shown to be highly targeted to the epithelial and myoepithelial compartment of both virgin and lactating mammary tissue [25], but mosaicism of Cre-expression amongst the differentiated cell types of the mammary gland suggests a lack of full penetrance throughout the mammary gland stem cell population [29]. These findings imply that a small population of stem cells lacking Cre-recombination may in fact be able to drive mammary gland development and differentiation prior to the activation of MMTV and thus target gene excision. This phenomenon may explain the report of no effect of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) deletion on mammary gland development using MMTV-Cre recombination, when PTHrP has been shown to be critical to mammary gland growth in other models [36,37]. To address the deficits of the MMTV-Cre model, other models of mammary specific promoters of Cre-recombination could be used such as whey acidic protein, progesterone receptor or beta-lactuloglobin [25,38,39]. Each of the aforementioned models also possesses limitations on temporal and spatial expression of cre-recombinase, which confounds the ability to adequately study mammary gland development and function. While we acknowledge that the stem cells of our Sod2−/− model may still retain Sod2 function, using MMTV-driven Cre-recombination it was demonstrated that fully developed Sod2−/− mammary glands did in fact lack greater than 90% Sod2 mRNA and protein. These cells lacking Sod2 revealed no changes in overall quality or quantity of cellular structures, and they were able to normally lactate to sustain equal numbers of healthy pups as the Sod2L/L controls. Overall, while limitations of the MMTV-Cre model exist, the role of Sod2 in mammary gland growth, development, and function appears insignificant.

In conclusion, we have used a novel model of targeted Sod2 deletion to understand the role of Sod2 in mammary gland development in vivo. While no quantifiable differences were observed between Sod2−/− and Sod2L/L animals, we believe these results contribute a significant finding to redox developmental biology. Sod2 has repeatedly demonstrated a critical function to the development of mammalian organ systems, but we report for the first time a tissue apparently resistant to the loss of this anti-oxidant enzyme. Insight into the mechanism by which mammary tissue adapts or is resistant to amplified oxidative stress may increase our understanding of the tissue specific redox environment, and could lead to new targeted redox-based therapies in the future.

Highlights.

Manganese superoxide dismutase (Sod2) has been implicated in mammary pathology

We examine the role of Sod2 in post-natal gland and development

No structural differences were noted histologically in Sod2 deficient mammary glands

Sod2 deficient mammary glands were able to lactate normally to sustain healthy pups

We first report mammary tissue as resistant to increased oxidative stress by Sod2 loss

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Iowa Comparative Pathology Laboratory for their help in histology and analysis.

Abbreviations

- Sod2

manganese superoxide dismutase

- MMTV

mouse mammary tumor virus

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Sod2L/L

control loxP containing mouse

- Sod2−/−

conditional Sod2 knock-out mouse

- Sod1

copper/zinc superoxide dismutase

- Cat

catalase

- Gpx1

glutathione peroxidase 1

- PTHrP

parathyroid hormone related protein

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no financial, consulting, or personal conflicts of interest pertaining to this work.

This work was supported by the following grants: NIH RO1 CA073612, NIH RO1 CA115438, DOD PC073831, and T32 CA078586.

Author contributions

A.J.C. performed or aided in all analyses; F.E.D. was principle investigator of study providing support, facilities, and supplies. A.J.C. and F.E.D. contributed equally in writing of the article.

References

- 1.Cowin P, Wysolmerski J. Molecular mechanisms guiding embryonic mammary gland development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003251. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson CJ, Oliver CH, Khaled WT. Cytokine signalling in mammary gland development. J Reprod immunol. 2011;88:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dulbecco R, Henahan M, Armstrong B. Cell types and morphogenesis in the mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7346–7350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi S, Hass R. Extracellular signals in young and aging breast epithelial cells and possible connections to age-associated breast cancer development. Mec Ageing Dev. 2011;132:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Transcriptional regulators in mammary gland development and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1034–1051. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang X, Lu B, Scott GK, Chang CH, Baldwin MA, Benz CC. Oxidant stress impaired DNA-binding of estrogen receptor from human breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;146:151–161. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maziere C, Conte MA, Maziere JC. Activation of JAK2 by the oxidative stress generated with oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1334–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schieffer B, Luchtefeld M, Braun S, Hilfiker A, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Drexler H. Role of NAD(P)H oxidase in angiotensin II-induced JAK/STAT signaling and cytokine induction. Circulation. 2000;87:1195–1201. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Jope RS. Oxidative stress differentially modulates phosphorylation of ERK, p38 and CREB induced by NGF or EGF in PC12 cells. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bianchi MS, Bianchi NO, Bolzan AD. Superoxide dismutase activity and superoxide dismutase-1 gene methylation in normal and tumoral human breast tissues. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1992;59:26–29. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(92)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werts ED, Gould MN. Relationships between cellular superoxide dismutase and susceptibility to chemically induced cancer in the rat mammary gland. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:1197–1201. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.7.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li JJ, Oberley LW, Fan M, Colburn NH. Inhibition of AP-1 and NF-kappaB by manganese-containing superoxide dismutase in human breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 1998;12:1713–1723. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.15.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Khaletskiy A, Wang J, Wong JY, Oberley LW, Li JJ. Genes regulated in human breast cancer cells overexpressing manganese-containing superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:260–267. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manna SK, Zhang HJ, Yan T, Oberley LW, Aggarwal BB. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis and activation of nuclear transcription factor-kappaB and activated protein-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13245–13254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bos R, Zhong H, Hanrahan CF, Mommers EC, Semenza GL, Pinedo HM, et al. Levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha during breast carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:309–314. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberley LW, Buettner GR. Role of superoxide dismutase in cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1979;39:1141–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Case AJ, McGill JL, Tygrett LT, Shirasawa T, Spitz DR, Waldschmidt TJ, et al. Elevated mitochondrial superoxide disrupts normal T cell development, impairing adaptive immune responses to an influenza challenge. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hitchler MJ, Oberley LW, Domann FE. Epigenetic silencing of SOD2 by histone modifications in human breast cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hitchler MJ, Wikainapakul K, Yu L, Powers K, Attatippaholkun W, Domann FE. Epigenetic regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase expression in human breast cancer cells. Epigenetics. 2006;1:163–171. doi: 10.4161/epi.1.4.3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebovitz RM, Zhang H, Vogel H, Cartwright J, Jr, Dionne L, Lu N, et al. Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury, and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9782–9787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson JL, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat Genet. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parmar H, Melov S, Samper E, Ljung BM, Cunha GR, Benz CC. Hyperplasia, reduced E-cadherin expression, and developmental arrest in mammary glands oxidatively stressed by loss of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Breast. 2005;14:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikegami T, Suzuki Y, Shimizu T, Isono K, Koseki H, Shirasawa T. Model mice for tissue-specific deletion of the manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:729–736. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00933-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner KU, Wall RJ, St-Onge L, Gruss P, Wynshaw-Boris A, Garrett L, et al. Cre-mediated gene deletion in the mammary gland. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4323–4330. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyerholz DK, Williard DE, Grittmann AM, Samuel I. Murine pancreatic duct ligation induces stress kinase activation, acute pancreatitis, and acute lung injury. Am J Surg. 2008;196:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lustgarten M, Jang Y, Liu Y, Muller F, Qi W, Steinhelper M, et al. Conditional knockout of MnSOD targeted to type IIB skeletal muscle fibers increases oxidative stress and is sufficient to alter aerobic exercise capacity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C1520–C1532. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00372.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misawa H, Nakata K, Matsuura J, Moriwaki Y, Kawashima K, Shimizu T, et al. Conditional knockout of Mn superoxide dismutase in postnatal motor neurons reveals resistance to mitochondrial generated superoxide radicals. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner KU, McAllister K, Ward T, Davis B, Wiseman R, Hennighausen L. Spatial and temporal expression of the Cre gene under the control of the MMTV-LTR in different lines of transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 2001;10:545–553. doi: 10.1023/a:1013063514007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenart J, Dombrowski F, Gorlach A, Kietzmann T. Deficiency of manganese superoxide dismutase in hepatocytes disrupts zonated gene expression in mouse liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;462:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui Y, Miyoshi K, Claudio E, Siebenlist UK, Gonzalez FJ, Flaws J, et al. Loss of the peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) does not affect mammary development and propensity for tumor formation but leads to reduced fertility. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17830–17835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krempler A, Qi Y, Triplett AA, Zhu J, Rui H, Wagner KU. Generation of a conditional knockout allele for the Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) gene in mice. Genesis. 2004;40:52–57. doi: 10.1002/gene.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurley SJ, Bierie B, Carnahan RH, Lobdell NA, Davis MA, Hofmann I, et al. p120-catenin is essential for terminal end bud function and mammary morphogenesis. Development. 2012;139:1754–1764. doi: 10.1242/dev.072769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemade RV, Bierie B, Nozawa M, Bry C, Smith GH, Vasioukhin V, et al. Biogenesis and function of mouse mammary epithelium depends on the presence of functional alpha-catenin. Mech Dev. 2004;121:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toyo-oka K, Bowen TJ, Hirotsune S, Li Z, Jain S, Ota S, et al. Mnt-deficient mammary glands exhibit impaired involution and tumors with characteristics of myc overexpression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5565–5573. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boras-Granic K, VanHouten J, Hiremath M, Wysolmerski J. Parathyroid hormone-related protein is not required for normal ductal or alveolar development in the post-natal mammary gland. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunbar ME, Dann P, Brown CW, Van Houton J, Dreyer B, Philbrick WP, Wysolmerski JJ. Temporally regulated over-expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the mammary gland reveals distinct fetal and pubertal phenotypes. J Endocrinol. 2001;171:403–416. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1710403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selbert S, Bentley DJ, Melton DW, Rannie D, Lourenco P, Watson CJ, Clarke AR. Efficient BLG-Cre mediated gene deletion in the mammary gland. Transgenic Res. 1998;7:387–396. doi: 10.1023/a:1008848304391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soyal SM, Mukherjee A, Lee KY, Li J, Li H, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP. Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis. 2005;41:58–66. doi: 10.1002/gene.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]