Abstract

Background

Germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH) is a neurological disease of very low birth weight premature infants leading to post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus, cerebral palsy, and mental retardation. Hydrogen (H2) is a potent antioxidant shown to selectively reverse cytotoxic oxygen-radical injury in the brain. This study investigated the therapeutic effect of hydrogen gas after neonatal GMH injury.

Methods

Neonatal rats underwent stereotaxic infusion of clostridial collagenase into the right germinal matrix brain region. Cognitive function was assessed at 3 weeks, and then sensorimotor function, cerebral, cardiac and splenic growths were measured 1 week thereafter.

Results

Hydrogen gas inhalation markedly suppressed mental retardation and cerebral palsy outcomes in rats at the juvenile developmental stage. The administration of H2 gas, early after neonatal GMH, also normalized the brain atrophy, splenomegaly and cardiac hypertrophy 1 month after injury.

Conclusion

This study supports the role of cytotoxic oxygen-radical injury in early neonatal GMH. Hydrogen gas inhalation is an effective strategy to help protect the infant brain from the post-hemorrhagic consequences of brain atrophy, mental retardation and cerebral palsy. Further studies are necessary to determine the mechanistic basis of these protective effects.

Keywords: Hydrogen gas, Neurological deficits, Stroke, experimental

Introduction

Germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH) is a clinical condition where immature blood vessels rupture within the sub- ventricular (anterior caudate) region during the first week of life [1, 2]. This affects approximately 3.5 per 1,000 births in the United States each year [3]. The clinical consequences are hydrocephalus (post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilation), developmental delay, cerebral palsy and mental retardation [4, 5]. Although this is an important clinical problem, experimental studies investigating thearapeutic modalities are lacking [6].

Interventions that target free-radical mechanisms are neuroprotective after brain hemorrhage in adult rats [7–10]. The lysis of red-blood cells after bleeding leads to the release of hemoglobin and other neurotoxins like heme and iron [11–13]. Thrombin will also contribute to this free radical-mediated injury [14–16]. This leads to oxidative damage to proteins, lipids and DNA within the first day [15, 17–20]. As a therapeutic intervention, hydrogen gas is a potent antioxidant that can selectively attenuate neurotoxic oxygen radicals and is known to protect the brain after injury in adult rats after ischemic stroke [21].

In light of this evidence, we hypothesized that hydrogen gas can be a therapeutic strategy for the amelioration of free-radical-mediated brain injury mechanisms. This can improve juvenile cognitive and sensorimotor outcomes after germinal matrix hemorrhage in neonatal rats.

Methods and Materials

Animal Groups and General Procedures

This study was in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the treatment of animals and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Loma Linda University. Timed pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were housed with food and water available ad libitum. Treatment consisted of 1 h of hydrogen gas (2.9%, mixed with air and oxygen) administered at 1 h after collagenase infusion. Postnatal day 7 (P7) pups were blindly assigned to the following (n = 8/group): sham (naive), needle (control), needle + hydrogen gas (treatment control), GMH (collagenase-infusion) and GMH + hydrogen gas (treatment). All groups were evenly divided within each litter.

Experimental Model of GMH

Using aseptic technique, rat pups were gently anaesthetized with 3% isoflurane (in mixed air and oxygen) while placed prone onto a stereotaxic frame. Betadine sterilized the surgical scalp area, which was incised in the longitudinal plane to expose the skull and reveal the bregma. The following stereotactic coordinates were determined: 1 mm (anterior), 1.5 mm (lateral) and 3.5 mm (ventral) from bregma. A bore hole (1 mm) was drilled, into which a 27-gauge needle was inserted at a rate of 1 mm/min. A microinfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) infused 0.3 units of clostridial collagenase VII-S (Sigma, St Louis, MO) through a Hamilton syringe. The needle remained in place for an additional 10 min after injection to prevent back-leakage. After needle removal, the burr hole was sealed with bone wax, the incision sutured closed and the animals allowed to recover. The entire surgery took on average 20 min. Upon recovering from anesthesia, the animals were returned to their dams. Needle controls consisted of needle insertion alone without collagenase infusion, while naïve animals did not receive any surgery.

Cognitive Measures

Higher order brain function was assessed during the third week after collagenase infusion. The T-maze assessed short-term (working) memory [22]. Rats were placed into the stem (40 cm × 10 cm) of a maze and allowed to explore until one arm (46 cm × 10 cm) was chosen. From the sequence of ten trials, of left and right arm choices, the rate of spontaneous alternation (0% = none and 100% = complete, alternations/trial) was calculated, as routinely performed [23, 24]. The Morris water maze assessed spatial learning and memory on four daily blocks, as described previously in detail [25, 26]. The apparatus consisted of a metal pool (110 cm diameter), filled to within 15 cm of the upper edge, with a platform (11 cm diameter) for the animal to escape onto, that changed location for each block (maximum = 60 s/ trial), and the data were digitally analyzed by Noldus Ethovision tracking software. Cued trials measured place learning with the escape platform visible above water. Spatial trials measured spatial learning with the platform submerged, and probe trials measured spatial memory once the platform was removed. For the locomotor activity, in an open field, the path length in open-topped plastic boxes (49 cm-long, 35.5 cm-wide, 44.5 cm-tall) was digitally recorded for 30 min and analyzed by Noldus Ethovision tracking software [26].

Sensorimotor Function

At 4 weeks after collagenase infusion, the animals were tested for functional ability. Neurodeficit was quantified using a summation of scores (maximum = 12) given for (1) postural reflex, (2) proprioceptive limb placing, (3) back pressure towards the edge, (4) lateral pressure towards the edge, (5) forelimb placement, and (6) lateral limb placement (2 = severe, 1 = moderate, 0 = none), as routinely performed [23]. For the rotarod, striatal ability was assessed using an apparatus consisting of a horizontal, accelerated (2 rpm/5 s), rotating cylinder (7 cm-diameter × 9.5 cm-wide), requiring continuous walking to avoid falling recorded by photobeam circuit (Columbus Instruments) [25, 26]. For foot fault, the number of complete limb missteps through the openings was counted over 2 min while exploring over an elevated wire (3 mm) grid (20 cm × 40 cm) floor [24].

Assessment of Treatment upon Cerebral and Somatic Growth

At the completion of the experiments, the brains were removed and hemispheres separated by midline incision (loss of brain weight has been used as the primary variable to estimate brain damage in juvenile animals after neonatal brain injury [27]). For organ weights, the spleen and heart were separated from surrounding tissue and vessels. The quantification was performed using an analytical microbalance (model AE 100; Mettler Instrument Co., Columbus, OH) capable of 1.0 μg precision.

Statistical Analysis

Significance was considered at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with repeated measures (RM-ANOVA) for long-term neurobehavior. Significant interactions were explored with conservative Scheffé post hoc and Mann-Whitney rank sum when appropriate.

Results

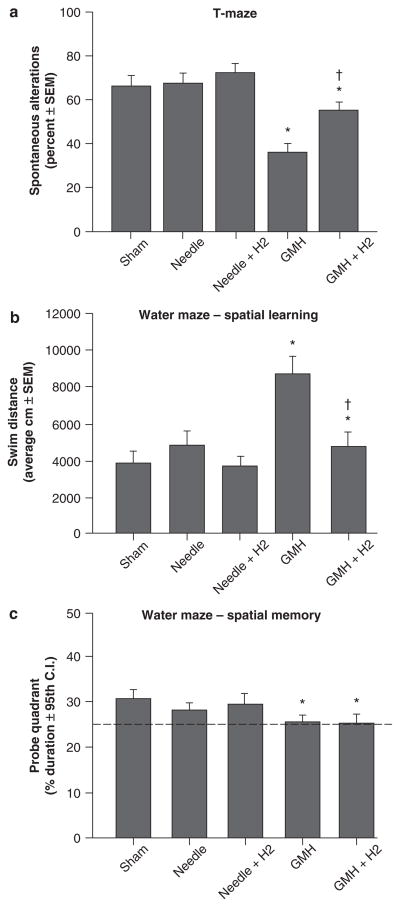

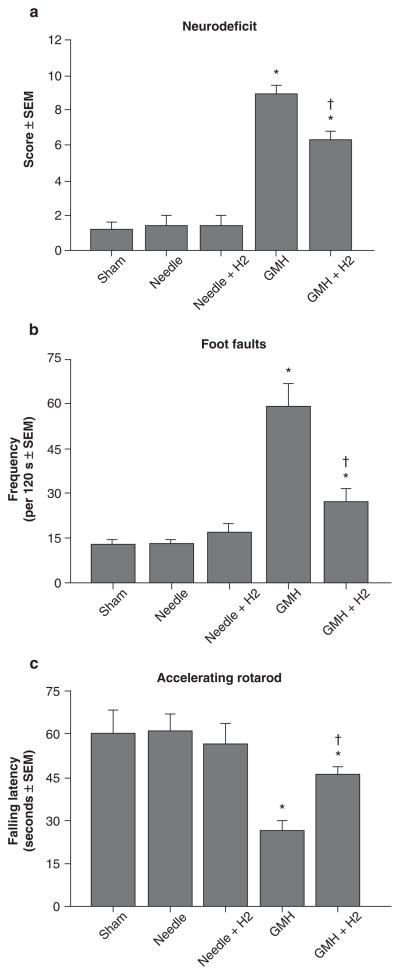

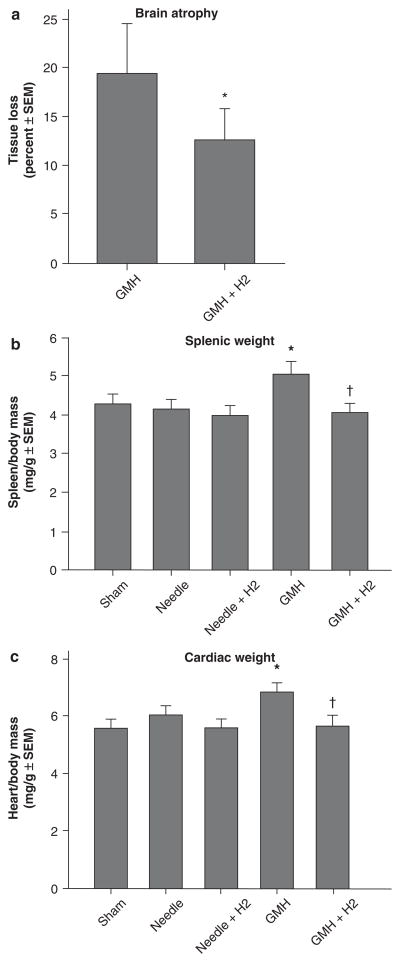

Collagenase infusion led to significant cognitive dysfunction in the T maze (working) memory and water maze (spatial) learning and memory (Fig. 1a–c, p < 0.05), while hydrogen inhalation significantly ameliorated T maze and water maze (spatial) learning deficits (Fig. 1a, b, p < 0.05), without improving spatial memory (Fig. 1c, p > 0.05). H2 also normalized (p < 0.05) sensorimotor dysfunction in juvenile GMH animals as shown by the neurodeficit score, number of foot faults and accelerating rotarod falling latency (Fig. 2a–c, p < 0.05). Neurological amelioration by hydrogen was confirmed with improvement upon brain atrophy, splenomegaly and cardiomegaly, compared to the juvenile vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 3a–c, p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Cognitive function normalization in juvenile rats by hydrogen gas (H2) after neonatal GMH. Higher order function was measured at the third week after collagenase infusion: (a) T maze, (b) spatial learning water maze, (c) spatial memory (probe) water maze. Values expressed as mean ± 95th CI (probe quadrant) or mean ± SEM (all others), n = 8 (per group), *p < 0.05 compared with controls (sham and needle trauma) and †p < 0.05 compared with GMH

Fig. 2.

Sensorimotor function normalization in juvenile rats by hydrogen gas (H2) after neonatal GMH. Cerebral palsy measurements were performed in the juveniles at 1 month after collagenase infusion: (a) neurodeficit score, (b) foot faults and (c) rotarod. Values expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8 (per group), *p < 0.05 compared with controls (sham and needle trauma), and †p < 0.05 compared with GMH

Fig. 3.

Cerebral and somatic growth normalization in juvenile rats by hydrogen gas (H2) after GMH. (a) Brain atrophy (percent tissue loss), (b) splenic weight and (c) cardiac weight were measured at 4 weeks after injury. Values expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8 (per group), *p< 0.05 compared with controls (sham and needle trauma), and †p< 0.05 compared with GMH

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that the inhalation of hydrogen gas, early after neonatal GMH, can improve brain atrophy, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, splenomegaly and cardiac hypertrophy in juvenile animals 1 month later. The therapeutic implications of H2 inhalation point to the pathophysiological role of cytotoxic oxygen-radical injury [21]. These outcomes support the findings from other brain injury studies to provide preliminary evidence about the importance of oxidative stress mechanisms on outcomes after neonatal GMH [7, 8, 10].

H2 inhalation is a neuroprotectant shown to ameliorate brain injury in an adult animal model of cerebral ischemia [21]. This study supports the notion that the hydrogen gas has no adverse affects in neonatal rats, and can be applied as a strategy to improve functional outcomes after brain injury from hemorrhagic stroke in premature infants. Further investigation is needed to determine the mechanistic basis of these neuroprotective effects.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by a grant (NS053407) from the National Institutes of Health to J.H.Z.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Tim Lekic, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

Anatol Manaenko, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

William Rolland, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

Nancy Fathali, Department of Human Pathology and Anatomy, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

Mathew Peterson, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

Jiping Tang, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

John H. Zhang, Email: johnzhang3910@yahoo.com, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA and Department of Human Pathology and Anatomy, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA and Department of Neurosurgery, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA and Department of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Risley Hall, Room 223, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA

References

- 1.Ballabh P. Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants: mechanism of disease. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:1–8. doi: 10.1203/ PDR.0b013e3181c1b176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadri H, Mawla AA, Kazah J. The incidence, timing, and predisposing factors of germinal matrix and intraventricular hemorrhage (GMH/IVH) in preterm neonates. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1086–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heron M, Sutton PD, Xu J, Ventura SJ, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2007. Pediatrics. 2010;125:4–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2416. peds.2009-2416 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M. The blood-brain barrier: an overview: structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.016. S0969996103002833 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy BP, Inder TE, Rooks V, Taylor GA, Anderson NJ, Mogridge N, Horwood LJ, Volpe JJ. Posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in the premature infant: natural history and predictors of outcome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87:F37–F41. doi: 10.1136/fn.87.1.F37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balasubramaniam J, Del Bigio MR. Animal models of germinal matrix hemorrhage. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:365–371. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peeling J, Del Bigio MR, Corbett D, Green AR, Jackson DM. Efficacy of disodium 4-[(tert-butylimino)methyl]benzene-1, 3-disulfonate N-oxide (NXY-059), a free radical trapping agent, in a rat model of hemorrhagic stroke. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:433–439. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00170-2. S0028390800001702 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peeling J, Yan HJ, Chen SG, Campbell M, Del Bigio MR. Protective effects of free radical inhibitors in intracerebral hemorrhage in rat. Brain Res. 1998;795:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00253-4. S0006-8993(98)00253-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peeling J, Yan HJ, Corbett D, Xue M, Del Bigio MR. Effect of FK-506 on inflammation and behavioral outcome following intracerebral hemorrhage in rat. Exp Neurol. 2001;167:341–347. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7564. S0014-4886(00)97564-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura T, Kuroda Y, Yamashita S, Zhang X, Miyamoto O, Tamiya T, Nagao S, Xi G, Keep RF, Itano T. Edaravone attenuates brain edema and neurologic deficits in a rat model of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:463–469. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486654. STROKEAHA.107.486654 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner KR, Sharp FR, Ardizzone TD, Lu A, Clark JF. Heme and iron metabolism: role in cerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:629–652. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000073905. 87928.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Hua Y, Keep RF, Nakamura T, Hoff JT, Xi G. Iron and iron-handling proteins in the brain after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003; 34:2964–2969. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000103140.52838.45. 01.STR.0000103140.52838.45 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:53–63. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70283-0. S1474-4422(05)70283-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xi G, Wagner KR, Keep RF, Hua Y, de Courten-Myers GM, Broderick JP, Brott TG, Hoff JT. Role of blood clot formation on early edema development after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1998;29:2580–2586. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.12.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura T, Keep RF, Hua Y, Hoff JT, Xi G. Oxidative DNA injury after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2005;1039:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres. 2005.01.036. S0006-8993(05)00104-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KR, Colon GP, Betz AL, Keep RF, Kim S, Hoff JT. Edema from intracerebral hemorrhage: the role of thrombin. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:91–96. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.1.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Erythrocytes and delayed brain edema formation following intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:991–996. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang FP, Xi G, Keep RF, Hua Y, Nemoianu A, Hoff JT. Brain edema after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: role of hemoglobin degradation products. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:287–293. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.2.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura T, Keep RF, Hua Y, Nagao S, Hoff JT, Xi G. Iron-induced oxidative brain injury after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006;96:194–198. doi: 10.1007/3-211-30714-1_42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao X, Sun G, Zhang J, Strong R, Song W, Gonzales N, Grotta JC, Aronowski J. Hematoma resolution as a target for intracerebral hemorrhage treatment: role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in microglia/macrophages. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:352–362. doi: 10.1002/ana.21097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohsawa I, Ishikawa M, Takahashi K, Watanabe M, Nishimaki K, Yamagata K, Katsura K, Katayama Y, Asoh S, Ohta S. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat Med. 2007;13:688–694. doi: 10.1038/nm1577. nm1577 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes RN. The value of spontaneous alternation behavior (SAB) as a test of retention in pharmacological investigations of memory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.06.006. S0149-7634(04)00073-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fathali N, Ostrowski RP, Lekic T, Jadhav V, Tong W, Tang J, Zhang JH. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition provides lasting protection against neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:572–578. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Fathali N, Lekic T, Tang J, Zhang JH. Glibenclamide improves neurological function in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1270:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.010. S0006-8993(09)00520-4 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lekic T, Hartman R, Rojas H, Manaenko A, Chen W, Ayer R, Tang J, Zhang JH. Protective effect of melatonin upon neuropathology, striatal function, and memory ability after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:627–637. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartman R, Lekic T, Rojas H, Tang J, Zhang JH. Assessing functional outcomes following intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1280:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.038. S0006-8993(09)00957-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andine P, Thordstein M, Kjellmer I, Nordborg C, Thiringer K, Wennberg E, Hagberg H. Evaluation of brain damage in a rat model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemia. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;35:253–260. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]