Abstract

Background

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is one of the most common causes of maternal deaths related to the postpartum period. This is a devastating form of stroke for which there is no available treatment. Although premenopausal females tend to have better outcomes after most forms of brain injury, the effects of pregnancy and child birth lead to wide maternal physiological changes that may predispose the mother to an increased risk for stroke and greater initial injury.

Methods

Three different doses of collagenase were used to generate models of mild, moderate and severe cerebellar hemorrhage in postpartum female and male control rats. Brain water, blood-brain barrier rupture, hematoma size and neurological evaluations were performed 24 h later.

Results

Postpartum female rats had worsened brain water, blood-brain barrier rupture, hematoma size and neurological evaluations compared to their male counterparts.

Conclusion

The postpartum state reverses the cytoprotective effects commonly associated with the hormonal neuroprotection of (premenopausal) female gender, and leads to greater initial injury and worsened neurological function after cerebellar hemorrhage. This experimental model can be used for the study of future treatment strategies after postpartum brain hemorrhage, to gain a better understanding of the mechanistic basis for stroke in this important patient subpopulation.

Keywords: Postpartum, Neurological deficits, Intracerebral hemorrhage, Stroke

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a devastating complication of pregnancy that accounts for 1 out of 14 deaths within this subpopulation in the United States [1]. ICH is the least treatable form of stroke [2] and has an approximate 20% mortality rate when related to pregnancy [1]. Survivors retain significant brain injury and life-long neurological deficits [3, 4], with most rehabilitating patients remaining unable to be “independent” 6 months later [5]. Matched for age and gender, the relative risk for ICH is increased 30-fold during the postpartum period [6].

Almost half of the cases of postpartum ICH occur in patients with eclampsia [7], and this is associated with hemostatic elevations of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression, brain edema and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption [8]. The cerebellum contains some of the highest levels of AQP4 [9] and is one of the brain locations with the greatest AQP4 increases during the postpartum period [10]. Therefore, this brain region could be a good model to study maternal mechanisms of ICH occurring during the postpartum period.

Clostridial collagenase is a stereotaxically infused enzyme that mimics spontaneous (ICH) vascular rupture, permitting investigations targeting hemostasis and neurobehavioral outcome [11–17]. We therefore hypothesized that unilateral cerebellar collagenase infusion in postpartum rats could model important clinical features [18–24]. This experimental approach may increase the pathophysiological understanding of this disease to direct future applications of therapeutic interventions [25].

Materials and Methods

The Animals and General Procedures

One hundred and nine adult Sprague-Dawley rats (290–345 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were used. All procedures were in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Loma Linda University. Surgeries were carried out using isoflurane anesthesia with aseptic techniques, and animals were given food and water during recovery [13, 14].

Model of Cerebellar Hemorrhage

Anesthetized animals were secured prone onto a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) before an incision was made over the scalp. The following stereotactic coordinates were measured from the bregma: 11.6 mm (caudal), 2.4 mm (lateral) and 3.5 mm (deep). A (1-mm) borehole was drilled, and then a 27-gauge needle was inserted. Collagenase VII-S (0.2 U/μl, Sigma, St Louis, MO) was infused by microinfusion pump (rate = 0.2 μl/min, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). The syringe remained in place for 10 min to prevent back-leakage before being withdrawn. Then the borehole was sealed with bone wax, the incision sutured closed and animals allowed to recover. Control surgeries consisted of needle insertion alone. A thermostat-controlled heating blanket maintained the core temperature (37.0°C ± 0.5°C) throughout the operation.

Cerebellar Water

Water content was measured using the wet-weight/dry-weight method [26]. Quickly after sacrifice the brains were removed, and tissue weights were determined before and after drying for 24 h in a 100°C oven, using an analytical microbalance (model AE 100; Mettler Instrument Co., Columbus, OH) capable of measuring with 1.0-μg precision. The data were calculated as the percentage of water content: (wet weight – dry weight)/wet weight × 100.

Neurological Score

This was assessed using a modified Luciani scale [24], which is a summation of scores (maximum = 9) given for (1) decreased body tone, (2) ipsilateral limb extensions and (3) dyscoordination (0 = severe, 1 = moderate, 2 = mild, 3 = none). Scores are represented as percent of sham.

Animal Perfusion and Tissue Extraction

Animals were fatally anesthetized with isoflurane (≥%5) followed by cardiovascular perfusion with ice-cold PBS for the hemoglobin and Evans blue assays, and immunoblot analyses. The cerebella were then dissected and snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored in −80°C freezer, before spectrophotometric quantifications or protein extraction.

Hematoma Volume

The spectrophotometric hemoglobin assay was performed as previously described [26], where extracted cerebellar tissue was placed in glass test tubes with 3 mL of distilled water, then homogenized for 60 s (Tissue Miser Homogenizer; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Ultrasonication for 1 min lysed erythrocyte membranes (then centrifuged for 30 min), and Drabkin’s reagent was added (Sigma-Aldrich) into aliquots of supernatant that reacted for 15 min. Absorbance, using a spectrophotometer (540 nm; Genesis 10uv; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), was calculated into hemorrhagic volume on the basis of a standard curve [27].

Vascular Permeability

Under general anesthesia, the left femoral vein was catheterized for 2% intravenous Evans blue injection (5 ml/kg; 1 h circulation). Extracted cerebellar tissue was weighed, homogenized in 1 ml PBS, then centrifuged for 30 min, after which 0.6 ml of the supernatant was added with equal volumes of trichloroacetic acid, followed by overnight incubation and re-centrifugation. The final supernatant underwent spectrophotometric quantification (615 nm; Genesis 10uv; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) of extravasated dye, as described [28].

Western Blotting

As routinely done [26], the concentration of protein was determined using DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for 80 min at 70 V (Bio-Rad). Blotting membranes were incubated for 2 h with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated overnight with the following primary antibodies: anti- AQP4 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-collagen IV (1:500; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and anti-zonula occludens (ZO)-1 (1:500; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). This was followed by incubation with secondary antibodies (1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and processed with ECL plus kit (Amersham Bioscience, Arlington Heights, Ill). Images were analyzed semiquantitatively using Image J (4.0, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05. Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant interactions were explored with T-test (unpaired) and Mann-Whitney rank sum test when appropriate.

Results

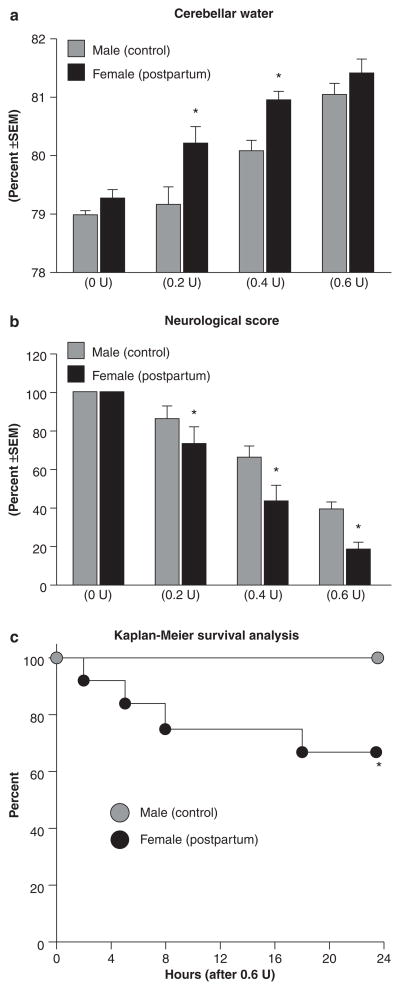

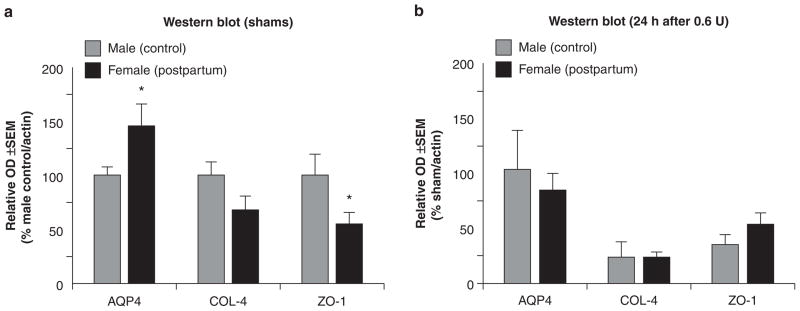

Collagenase infusion led to dose-dependent elevations of cerebellar water and neurodeficit (Figs. 1a, b). Compared to male controls, cerebellar water was significantly elevated in postpartum females at 0.2 and 0.4 units collagenase and neurodeficit across all doses (P < 0.05). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated a significantly increased mortality rate (Fig. 1c, P < 0.05) in postpartum females (approximately 30%) compared to male controls (0%). Collagenase infusion (0.6 U) led to a greater hematoma size (Fig. 2a) and vascular permeability (Fig. 2b) in postpartum females compared to male controls (P < 0.05). Immunoblots of shams (Fig. 3a) showed greater AQP4, and diminished COL-4 (collagen-IV) and ZO-1 expressions in postpartum females compared to male controls (P < 0.05), while collagenase infusion (0.6 U) injury was equivalent and did not cause any additional changes compared to respective shams (Fig. 3b, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Postpartum worsens outcomes at 24 h after collagenase infusion. (a) Cerebellar water, (b) neurological score and (c) survival analysis; groups consisted of males (control) and females (postpartum), receiving doses of 0, 0.2, 0.4 and 0.6 units collagenase. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5 (per group), *P < 0.05 compared with male (control)

Fig. 2.

Postpartum increases vascular rupture at 24 h after collagenase infusion. (a) Hematoma volume and (b) vascular permeability; the values are expressed as mean ± SD. Groups consisted of males (control) and female (postpartum), receiving doses of 0 and 0.6 units collagenase, n = 5 (per group), *P < 0.05 compared with respective shams and †P < 0.05 compared with male (0.6 units, control)

Fig. 3.

Postpartum rats have increased vascular vulnerability. (a and b) Semi-quantification of immunoblots for AQP4, collagen-IV (COL-4) and ZO-1 groups consisted of males (control) and females (postpartum), receiving doses of 0 and 0.6 units of collagenase. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5 (per group), *P < 0.05 compared with males (control)

Discussion

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the least treatable form of stroke clinically and is a devastating complication after pregnancy accompanied by life-long neurodeficits [1–6]. This study infused collagenase into the unilateral (right) side of the cerebellar hemisphere of postpartum rats as an approach to model these features, since available animal models to study the pathophysiological basis of these outcomes are lacking.

Our results are in support of the clinical evidence for cerebral vascular vulnerability in the postpartum period. Around half of the cases of ICH in this patient population will have eclampsia [7], and this is related to hemostatically relevant increases of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression, blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption and brain edema [8]. In agreement, we found greater AQP4, and diminished COL-4 (collagen-IV) and ZO-1 expressions in the cerebella of postpartum female shams compared to the male controls. The collagenase model is an ideal method for study since it did not alter these levels any further; however, the increased vascular vulnerability in postpartum animals led to greater brain edema, neurodeficit, BBB rupture and hematoma size across most doses studied. The lack of significant difference in cerebellar water at the highest collagenase dose (0.6 U) is likely either a reflection of mortality (i.e., severely injured animals died) or due to the high baseline AQP4 expressions leading to an edematous outflow.

In summary, we have characterized a highly reliable and easily reproducible experimental model of intracerebral hemorrhage using postpartum rats. Since the cerebellum contains some of the highest levels of AQP4 [9] with the greatest AQP4 increase during the postpartum period [10], this ICH model provides a basis for studying the clinical and pathophysiological features of this disease while establishing a foundation for performing further preclinical therapeutic investigations.

Acknowledgments

This study is partially supported by NIH NS053407 to J.H. Zhang and NS060936 to J. Tang.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Tim Lekic, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

Robert P. Ostrowski, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA

Hidenori Suzuki, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

Anatol Manaenko, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

William Rolland, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

Nancy Fathali, Department of Human Pathology and Anatomy, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda CA 92354, USA.

Jiping Tang, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA.

John H. Zhang, Email: johnzhang3910@yahoo.com, Departments of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA and Department of Human Pathology and Anatomy, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda CA 92354, USA and Department of Neurosurgery, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA and Department of Physiology, Loma Linda University, School of Medicine, Risley Hall, Room 223, Loma Linda, CA, 92354, USA

References

- 1.Bateman BT, Schumacher HC, Bushnell CD, Pile-Spellman J, Simpson LL, Sacco RL, Berman MF. Intracerebral hemorrhage in pregnancy: frequency, risk factors, and outcome. Neurology. 2006;67:424–429. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228277.84760.a2. 67/3/424 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciccone A, Pozzi M, Motto C, Tiraboschi P, Sterzi R. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic aspects of primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Sci. 2008;29(Suppl 2):S256–257. doi: 10.1007/s10072-008-0955-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skriver EB, Olsen TS. Tissue damage at computed tomography following resolution of intracerebral hematomas. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1986;27:495–500. doi: 10.1177/028418518602700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broderick JP, Adams HP, Jr, Barsan W, Feinberg W, Feldmann E, Grotta J, Kase C, Krieger D, Mayberg M, Tilley B, Zabramski JM, Zuccarello M. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 1999;30:905–915. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebel JM, Broderick JP. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Clin. 2000;18:419–438. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kittner SJ, Stern BJ, Feeser BR, Hebel R, Nagey DA, Buchholz DW, Earley CJ, Johnson CJ, Macko RF, Sloan MA, Wityk RJ, Wozniak MA. Pregnancy and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:768–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609123351102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharshar T, Lamy C, Mas JL. Incidence and causes of strokes associated with pregnancy and puerperium. A study in public hospitals in Ile France. Stroke Pregnancy Study Group. Stroke. 1995;26:930–936. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quick AM, Cipolla MJ. Pregnancy-induced up-regulation of aquaporin-4 protein in brain and its role in eclampsia. FASEB J. 2005;19:170–175. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1901hyp. 19/2/170 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verkman AS. Physiological importance of aquaporin water channels. Ann Med. 2002;34:192–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiegman MJ, Bullinger LV, Kohlmeyer MM, Hunter TC, Cipolla MJ. Regional expression of aquaporin 1, 4, and 9 in the brain during pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2008;15:506–516. doi: 10.1177/1933719107311783. 15/5/506 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foerch C, Arai K, Jin G, Park KP, Pallast S, van Leyen K, Lo EH. Experimental model of warfarin-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:3397–3404. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.517482. STROKEAHA.108.517482 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacLellan CL, Silasi G, Poon CC, Edmundson CL, Buist R, Peeling J, Colbourne F. Intracerebral hemorrhage models in rat: comparing collagenase to blood infusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:516–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600548. 9600548 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lekic T, Hartman R, Rojas H, Manaenko A, Chen W, Ayer R, Tang J, Zhang JH. Protective effect of melatonin upon neuropathology, striatal function, and memory ability after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:627–637. doi: 10.1089/ neu.2009.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman R, Lekic T, Rojas H, Tang J, Zhang JH. Assessing functional outcomes following intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. BrainRes. 2009;1280:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j. brainres.2009.05.038. S0006-8993(09)00957-3[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andaluz N, Zuccarello M, Wagner KR. Experimental animal models of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2002;13:385–393. doi: 10.1016/s1042-3680(02)00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiex R, Mayfrank L, Rohde V, Gilsbach JM, Tsirka SA. The role of endogenous versus exogenous tPA on edema formation in murine ICH. Exp Neurol. 2004;189:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.20 04.05.021S0014488604001840. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg GA, Mun-Bryce S, Wesley M, Kornfeld M. Collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Stroke. 1990;21:801–807. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.5.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg GA, Kaufman DM. Cerebellar hemorrhage: reliability of clinical evaluation. Stroke. 1976;7:332–336. doi: 10.1161/01.str.7.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.St Louis EK, Wijdicks EF, Li H. Predicting neurologic deterioration in patients with cerebellar hematomas. Neurology. 1998;51:1364–1369. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly PJ, Stein J, Shafqat S, Eskey C, Doherty D, Chang Y, Kurina A, Furie KL. Functional recovery after rehabilitation for cerebellar stroke. Stroke. 2001;32:530–534. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolderer S, Kallenberg K, Aschoff A, Schwab S, Schwarz S. Long-term outcome after spontaneous cerebellar haemorrhage. Eur Neurol. 2004;52:112–119. doi: 10.1159/000080268. ENE2004052002112 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thach WT. On the specific role of the cerebellum in motor learning and cognition: clues from PET activation and lesion studies in man. Behav Brain Sci. 1996;19:411–431. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strick PL, Dum RP, Fiez JA. Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:413–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro. 31.060407.125606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baillieux H, De Smet HJ, Paquier PF, De Deyn PP, Marien P. Cerebellar neurocognition: insights into the bottom of the brain. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:763–773. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.05.013. S0303-8467(08)00169-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NINDS ICH Workshop Participants. Priorities for clinical research in intracerebral hemorrhage: report from a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke workshop. Stroke. 2005;36:e23–41. doi: 10.1161/01. STR.0000155685.77775.4c. 01.STR.0000155685.77775.4c [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Liu J, Zhou C, Alexander JS, Nanda A, Granger DN, Zhang JH. Mmp-9 deficiency enhances collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage and brain injury in mutant mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000135593.05952.DE. 00004647-200410000-00007 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhri TF, Hoh BL, Solomon RA, Connolly ES, Jr, Pinsky DJ. Use of a spectrophotometric hemoglobin assay to objectively quantify intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Stroke. 1997;28:2296–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saria A, Lundberg JM. Evans blue fluorescence: quantitative and morphological evaluation of vascular permeability in animal tissues. J Neurosci Methods. 1983;8:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(83)90050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]