Abstract

Purpose

Early childhood traumatic experiences (e.g., abuse or neglect) may contribute to sleep disturbances as well as other indicators of arousal found in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This study compared women with IBS positive for a history of childhood abuse and/or neglect to IBS women without this history, on daily gastrointestinal (GI), sleep, somatic, and psychological symptom distress, polysomnographic sleep, urine catecholamines and cortisol, and nocturnal heart rate variability (HRV).

Methods

Adult women with IBS recruited from the community were divided into 21 IBS with abuse/neglect and 19 IBS without abuse/neglect based on responses to the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect). Women were interviewed, maintained a 30-day symptom diary, and slept in a sleep laboratory. Polysomnographic and nocturnal heart rate variability data were obtained. First voided urine samples were assayed for cortisol and catecholamine levels.

Results

Women with IBS positive for abuse/neglect history were older than women without this history. Among GI symptoms, only heartburn and nausea were significantly higher in women with IBS with abuse/neglect. Sleep, somatic and psychological symptoms were significantly higher in women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group. With the exception of percent time in REM sleep, there were few differences in sleep stage variables and urine hormone levels. Mean heart rate interval and the Ln SDNN values were lower in those who experienced childhood abuse/neglect.

Conclusion

Women with IBS who self report childhood abuse/neglect are more likely to report disturbed sleep, somatic symptoms, and psychological distress. Women with IBS should be screened for adverse childhood events including abuse/neglect.

Worldwide approximately 7–10% of people report gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms compatible with a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (Spiegel, 2009). IBS is a functional GI disorder characterized by abdominal pain and alterations in bowel pattern (i.e., constipation, diarrhea, or mixed diarrhea-constipation). Patients with IBS frequently report a number of non-GI symptoms including poor sleep and fatigue (Kato, Sullivan, Evengard, & Pedersen, 2009). We, as well as others, have shown that patients with IBS self report poorer sleep quality (e.g., difficulty getting to sleep, awakening during the night) when compared to healthy controls (Jarrett, Heitkemper, Cain, Burr, & Hertig, 2000; Robert, Elsenbruch, & Orr, 2006; Ono, Komada, Kamiya, & Shirakawa, 2008; Elsenbruch, Thompson, Hamish, Exton, & Orr, 2002; Burr, Jarrett, Cain, Jun, & Heitkemper, 2009). Together these results suggest that IBS patients may be hyperaroused in relation to both internal and external stimuli. Chronic hyperarousal can be defined as an abnormal state of activation that can occur as a results of traumatic or highly stressful events (Kendall-Tackett, 2000).

The physical and psychological factors that contribute to hyperarousal in patients with IBS remain to be fully explicated. One predisposing factor may be childhood adverse events including emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse or loss of a parent through death or divorce. Approximately 30–50% of women with IBS report a history of early life adverse events including abuse (Chitkara, van Tilburg, Blois-Martin, & Whitehead, 2008; Drossman, 1997; Talley, Boyce, & Jones, 1998; Delvaux, Denis, & Allemand, 1997). In an early report Drossman found that a third of women with a functional bowel disorder had a history of rape or incest (Drossman, 1997). Delvaux reported that 31% (n = 62/196) of surveyed IBS patients reported a history of abuse in response to an anonymous, self-reporting survey (Delvaux et al., 1997). In a community survey in Minnesota, Talley reported that 22% of functional bowel disease patients had a history of abuse (13% sexual and / or physical abuse) (Talley et al., 1998). In addition they noted a significant association between IBS and abuse (sexual, emotional, verbal) history (Talley et al., 1998). Han and colleagues recently reported that 51 % of 72 women with IBS enrolled in a randomized clinical trial of paroxetine were positive for a history of childhood abuse/neglect (Han et al., 2009). In a systematic review of 25 studies, Chitkara found overall that for a proportion of patients with IBS their symptoms began in childhood and that those with the highest comorbid stress levels may be at greatest risk for symptom persistence (Chitkara et al., 2008).

In addition to IBS, a history of early childhood traumatic experiences is also associated with self-reported sleep disturbances and other pain-related conditions (Tietjen et al., 2009; Holly, Wegman, & Stetler, 2009; Heitkemper et al., 2005). However, a history of abuse/neglect has not been linked to subjective or objective sleep indices in patients with IBS. In an earlier report we found that women with severe IBS symptoms (abdominal pain, constipation or diarrhea) were significantly more likely to report a history of physical, emotional and sexual abuse (Heitkemper et al., 2005). The comparison group in that study also included women with a history of abuse and/or neglect, albeit the prevalence was much lower than in women with IBS. Given findings that childhood abuse has been associated with poor sleep it is logical to consider whether abuse history influences indicators of nighttime arousal such as increased catecholamine and cortisol excretion, reduced heart rate variability (HRV), and disturbed objective and subjective sleep measures in women with a positive history of abuse/neglect.

It has been suggested that adults with a history of severe negative experiences in childhood are more susceptible to stressors as adults (Maunder, Peladeau, Savage, & Lancee, 2010). For example, individuals with a history of abuse may be more likely to develop insomnia particularly when stressed. Laboratory studies involving comparisons of patients with and without abuse history have been limited. In a recent report Videlock and colleagues (Videlock et al., 2009) reported patients (men and women) with a history of early life adverse events demonstrate hyper-responsiveness as evidenced by increased salivary cortisol response to a visceral stressor (sigmoidoscopy). In their study of healthy controls and IBS patients, only salivary cortisol as a component of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis was measured.

The purpose of the current analysis was to compare women with IBS positive for a history of childhood abuse/neglect to women with IBS and no history of abuse/neglect on self report GI symptom, sleep, somatic and psychological distress severity, polysomnography-determined sleep quality, nocturnal HRV, and first void urine measures of catecholamines and cortisol. We hypothesized that those with a history of childhood abuse/neglect would report increased GI and other symptom distress, more sleep disruptions, reduced nocturnal HRV, and increased stress hormone secretion.

Methods

Design

Data were obtained as part of an observational study of sleep and GI symptoms in women with IBS (n = 40) and healthy comparison women (n = 36). Only healthy comparison women with no reported history of abuse or neglect are included in the analyses. Women in the control group were excluded if they had symptoms of a functional GI disorder. As previously described both healthy comparison women and women with IBS were recruited for a study of sleep and GI symptoms (Heitkemper et al., 2005). Within the IBS group comparisons were made based on the presence of a positive self-reported childhood history of emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse or neglect. Comparisons include measures of psychological distress, GI symptoms, sleep (self report and objective polysomnography [PSG]), urine cortisol and catecholamine levels, and HRV indices in addition to demographic characteristics.

Sample

The characteristics of the comparison group and the total IBS sample have been described elsewhere (Heitkemper et al., 2005). In brief, women with IBS and healthy control women, 18 to 46 years of age, were recruited through community advertisements. The study was conducted between 2001 and 2005. Women in the IBS group had to have a medical diagnosis of IBS and currently be experiencing symptoms compatible with the Rome-II criteria for IBS. Women in the comparison group were excluded if they had symptoms of a functional GI disorder. Exclusion criteria for both groups included they had: a) a history of GI pathology (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease), b) GI surgery, renal, or gynecological pathology that might result in IBS symptoms (e.g., bowel resection, endometriosis), c) a significant co-morbid condition (excluding treated hypothyroidism, mild asthma), d) had a known cardiac dysrhythmia, e) had a sleep disorder, f) were taking medications that could interfere with sleep, cortisol, catecholamines, or HRV, such as beta blockers, antihistamines, benzodiazepines, or antidepressants (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]), or g) GI prokinetic or serotonergic agents. Women could not be using hormonal contraceptive. Human subjects’ committee approval was obtained prior to recruitment. Of the women enrolled, four IBS and three control women withdrew from the study because they reconsidered the time the study would take, or had too low a hematocrit, or two anovulatory cycles). In addition, 8 women did not complete the sleep laboratory protocol (e.g., illness) but did complete their diary and PSQI questionnaire.

This report presents results from the 72 women (32 controls, 21 IBS women with a history of abuse/neglect, and 19 women with IBS and no history of abuse/neglect) who provided data on at least one of the outcome variables analyzed here. However, not all women provided all of the outcome variables, as can be seen by the varying Ns in the tables.

Procedures

Subjects came to the university sleep laboratory for their initial interview, gave written consent, completed questionnaires, and were oriented to the study procedures and sleep laboratory. The protocol began at the start of the woman’s next menses. The women completed a daily symptom diary for one menstrual cycle, tested their urine for the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge (ClearPlan Easy, Unipath Research: Princeton, NJ) and slept 3 nights in the laboratory on day 7 ( ± 2 days) after a positive LH surge, mid-luteal phase. Based on the menstrual cycle women collected a urine sample, first after waking, twice in the follicular phase, three times in luteal phase and day one or two of menses. The women were financially compensated for their participation in the study.

Sleep Assessment Protocol

The sleep assessment protocol has been described elsewhere (Heitkemper et al., 2005). For this analysis, only the second night data of a three-night sleep laboratory protocol was used. The first night was for adaptation to the laboratory and subjects were screened for apnea/hyponea and periodic leg movements (Heitkemper et al., 2005). On all nights prior to coming to the sleep laboratory, women were instructed to refrain from drinking caffeinated beverages, taking acetaminophen or aspirin within 6 hours of bedtime, drinking any alcohol, or napping. On the second night women came to the sleep laboratory 2 hours before their normal sleep time and had electrodes placed on their head, face, and chest, for a standard PSG assessment. Once the electrode placement was complete, subjects read or watched television in bed until their typical bedtime when the lights were turned out. The women were woken at their typical wake-up time.

Measures

Descriptive Characteristics

Demographic characteristics include age in years, ethnic affiliations, marital status, le.vel of formal education, type of work and job title, age when IBS pain began, and medication use. Body mass index (BMI) was computed based on the subjects’ self reported current height and weight.

Self-Reported Symptoms and Abuse

Abuse

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) is a 28-item tool that asks about five types of maltreatment (emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect) during childhood and adolescence. The questions are rated from never true (1) to very often true (5). An example question for sexual abuse is “Someone tried to touch me in a sexual way or tried to make me touch them.”, for physical abuse, “People in my family hit me so hard that it left me with bruises or marks.”, and emotional abuse, “People in my family called me things like “stupid,” “lazy,” or “ugly.” Three items make up the Minimization/Denial scale for detecting false-negative trauma reports. The mean score for each scale is computed and a threshold score for “caseness” (Bernstein et al., 1994). Confirmatory factor analyses and convergent validity supported the validity of the CTQ (Bernstein et al., 1994; Bernstein & Fink, 1998).

Daily Symptom Diary

Subjects completed a symptom diary that contained 26 symptoms, which were rated every evening. Each symptom was rated on a scale from 0 (not present) to 4 (extreme). GI pain/discomfort symptoms in the daily diary included abdominal pain, abdominal distension, bloating, intestinal gas, heartburn, and nausea. GI symptoms related to stool characteristics were diarrhea, constipation, and urgency. While results are presented for individual GI symptoms, non-GI symptoms are combined into scales: somatic (headache, backache, joint and muscle pain), anger (anger, hostility, irritability), anxiety (anxiety, nervousness/jittery, panic feelings), depression (decreased desire to talk or move, depressed/sad or blue, hopelessness), cognitive difficulty (forgetfulness, hard to concentrate, hard to make decisions, trouble with memory) and poor sleep (hard to fall asleep, waking up during the night, and wake up too early). Only participants who completed the daily diary were included in the analyses.

Sleep Quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) assesses sleep quality and disturbances over the prior month. It is composed of 19 items that are scored to determine 7 component scores: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). Each component is scored from 0 to 3 and summed into a global PSQI score. Internal consistency of the PSQI score was reported as α = .83 and test-retest reliability, with an average of 4 wks between testing, was r = .85. A global PSQI score >= 5 yielded a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% (κ = .75, p < .001) in distinguishing good from poor sleepers (Buysse et al., 1989). In an additional validation study, a global PSQI score >= 6 was predictive of primary insomnia (sensitivity = 84%; specificity of 99%) (Backhaus, Junghanns, Broocks, Riemann, & Hohagen, 2002).

Physiological Measures

Sleep Polysomnography (PSG)

PSG recording included electroencephalography (EEG) to assess brainwaves, electromyography (EMG) to assess muscle tension, and electrooculography (EOG) to detect eye movements. The EEG was recorded from the C3-A2 and C4-A1 electrode placement (Heitkemper et al., 2005; Stiasny, Oertel, & Trenkwalder, 2002; Klem, Luders, Jasper, & Elger, 1999). Recordings were done using an Embla Recording System with Somnologica software (Embla, Broomfield, CO). All records were prescreened for epochs with movement, breathing or muscle artifact, or recording difficulties; they were excluded from analysis. Sleep records were manually scored in 30 second epochs as wake, stages 1, 2, stage 3 and 4 (slow wave sleep) and 5 (REM) by an experienced technician based on Rechtschaffen and Kales scoring criteria (Rechtschaffen & Kales, 1968). Inter-rater agreement was ≥ 90% for a random 10% of each sleep record.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

ECG was recorded from a modified lead II, digitized with 16-bit amplitude resolution at 200 samples/sec, which places a nominal constraint on the accuracy of the estimation of the individual R-R interval lengths for HRV analysis to a resolution of about 5 milliseconds. Interbeat intervals were summarized in successive five minute blocks of normal sinus RR intervals and cross-linked with the manually scored PSG sleep stage codes. A discrete Fourier transform (DFT-FFT) spectral analysis algorithm was used for the development of the HRV spectral measures. Time domain (statistical) HRV measures were computed based on RR intervals (normal inter-beat intervals using the R-wave peak as the reference point measured in milliseconds) and differences in RR intervals. Parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) activity was assessed with spectral (Ln HF, natural log of the high frequency (HF) band power, f = 0.15 to 0.40 Hz) and time domain (Ln RMSSD, natural log of the root mean square of successive differences in RR intervals) measures. Mixed sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and PSNS activity was measured with two time domain measures (Ln SD5min, natural log of the average standard deviation of RR intervals within all 5 min blocks; Ln SDNN, natural log of the standard deviation of RR intervals for the entire sleep interval), and a spectral measure (Ln LF, natural log low frequency (LF) band power, f = 0.04 to 0.15 Hz). SNS/PSNS balance was indexed in the frequency domain (Square root LF/HF) (Kleiger, Stein, Bosner, & Rottman, 1992; Ori, Monir, Weiss, Sayhouni, & Singer, 1992; Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology, 1996). HRV measures were computed by averaging over all of the five-minute blocks throughout night 2.

Urine Measures. Urine catecholamines (CA) were measured by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) after extraction by cation exchange (Bio-Rex 70, BioRad Laboratories) followed by alumina oxide precipitation using a modification of the LCEC Application Note No. 15 (Bioanal.Syst., 1982). Urine samples will be preserved with Na2EDTA and Na2S205. Thawed samples will be mixed with pH 6.5 phosphate buffer with 1% NaEDTA. For reliability, 1 ml samples will be assayed in duplicate, using 1/5 the volume of solutions except for the perchlorate extraction of the CA from the alumni, 200µl will be still used. The 10µl samples in perchlorate will be run through a Beckman Ultrasphere ODS 5µm 4.6mm×25cm C-18 column using a Beckman autosampler, NECPC-8300 System Gold 116 solvent pump and ESA 5100A Coulochem Detector (guard cell, 0.35, detector 1; 0.05, and detector 2; −0.35 and gain of 25). Unknowns were determined from a standard curve made with 3 controls: clinical chemistry control I and II (Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp.) and a urine pool (Bioanal. Syst.). The values of these standards were determined by standard addition curves for each CA with 3,4 dihydroxybenzamine as an internal standard. The intra-assay variation was <5% and the inter-assay variation was <9%.

Urine cortisol was measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) using a kit from Diagnostic Products, Inc. (Los Angeles, CA), involving dichloromethane extraction of steroids. Aliquots of sample were added to tubes coated with antibodies against cortisol, exposed to iodinated cortisol and counted in a gamma counter. All assays were performed with duplicate samples and standards. The cortisol detection limit was 0.3µg/dl and there was low cross-reactivity with other steroids. Inter and intra-assay variations were 8.8% and 4.8%, respectively. Urine CA and cortisol were expressed per mg of creatinine as well as body surface area. Creatinine was measured by an autoanalyzer technique with urine buffered to pH 2.3. Body surface area was estimated from height and weight tables.

Statistical Analysis

Since the focus of this report is on the association of childhood abuse/neglect with symptom reports and physiological measures, all hypothesis test results shown relate to comparisons between the IBS with abuse/neglect and IBS without abuse/neglect groups. Summary statistics for the CTRL without abuse/neglect group are also presented, but for purely descriptive purposes.

Chi-square and t-tests are used to compare the IBS with abuse/neglect and the IBS without abuse groups. Since age is strongly associated with abuse/neglect status in this sample, ANCOVA and logistic regression are also used to compare the two groups, controlling for age. An alpha level of alpha .05 was used for significance.

Results

Abuse

A total of 21 IBS women reported a history of abuse/neglect and 19 women with IBS denied this history. The IBS abuse/neglect group included 16 women with a history of emotional abuse, 12 women with physical abuse and 12 women who reported sexual abuse. Six women reported all three types of abuse, 8 reported only one type (4 emotional, 2 physical, 2 sexual), and the remaining 7 reported 2 types of abuse. None of the women in the IBS groups reported a history of physical neglect and all 10 of the women with a history of emotional neglect also reported some other type of abuse.

Women in the IBS with abuse/neglect and IBS without abuse/neglect groups did not differ on race (72% white), education (52% with a college degree) or job type (32% professional). However, compared to the 19 women in the IBS without abuse/neglect group, the 21 women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group were older (mean 34.6 ± 7.9 versus 28.4 ± 7.2, p=.012), had lower income (income >$40,000, 24% versus 63%, p=.024), and were less likely to be married/partnered (19% versus 47%, p=.091).

Symptoms

Daily Gastrointestinal Symptoms

With the exception of heartburn and nausea there were no significant group differences in GI symptoms between IBS without abuse/neglect and IBS with abuse/neglect groups (Table 1). When used as a covariate age reduced the significance of these differences. Note that the sample sizes in the table reflect the fact that 3 subjects (2 IBS with abuse/neglect, 1 comparison) did not complete the daily diary.

Table 1.

Comparison of Gastrointestinal, Somatic, and Psychological Distress Symptoms in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with and without a History of Childhood Abuse and/or Neglect (mean ± SD)

| Comparison No-Abuse (n=31) |

IBS No- Abuse/Neglect (n=17) |

IBS- Abuse/Neglect (n=21) |

P1 | P2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI Symptoms | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 0.21 ± 0.34 | 1.44 ± 0.65 | 1.41 ± 0.71 | .909 | .610 |

| Bloating | 0.39 ± 0.46 | 1.09 ± 0.79 | 1.26 ± 0.78 | .518 | .631 |

| Constipation | 0.12 ± 0.18 | 0.70 ± 0.48 | 1.02 ± 0.92 | .204 | .276 |

| Diarrhea | 0.06 ± 0.11 | 0.33 ± 0.30 | 0.43 ± 0.59 | .520 | .694 |

| Intestinal gas | 0.41 ± 0.45 | 1.63 ± 0.86 | 1.60 ± 0.77 | .922 | .865 |

| Heartburn | 0.05 ± 0.11 | 0.19 ± 0.35 | 0.58 ± 0.62 | .028 | .061 |

| Nausea | 0.08 ± 0.13 | 0.22 ± 0.22 | 0.53 ± 0.64 | .035 | .071 |

| Somatica | 0.34 ± 0.39 | 0.56 ± 0.57 | 0.96 ± 0.57 | .043 | .099 |

| Psychological Distress | |||||

| Anger | 0.44 ± 0.45 | 0.37 ± 0.23 | 0.80 ± 0.65 | .013 | .015 |

| Anxiety | 0.39 ± 0.39 | 0.44 ± 0.32 | 0.68 ± 0.60 | .138 | .232 |

| Depression | 0.39 ± 0.50 | 0.32 ± 0.29 | 0.75 ± 0.57 | .007 | .112 |

| Cognitive Difficulties | 0.38 ± 0.39 | 0.65 ± 0.41 | 1.04 ± 0.65 | .042 | .145 |

| Sleep Problems | 0.28 ± 0.39 | 0.27 ± 0.31 | 0.70 ± 0.80 | .040 | .078 |

Note. P1 = unadjusted p-value, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only. P2 = p-value controlling for age, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only.

somatic symptoms include headache, backache, joint and muscle pain.

Daily Non-GI Symptoms

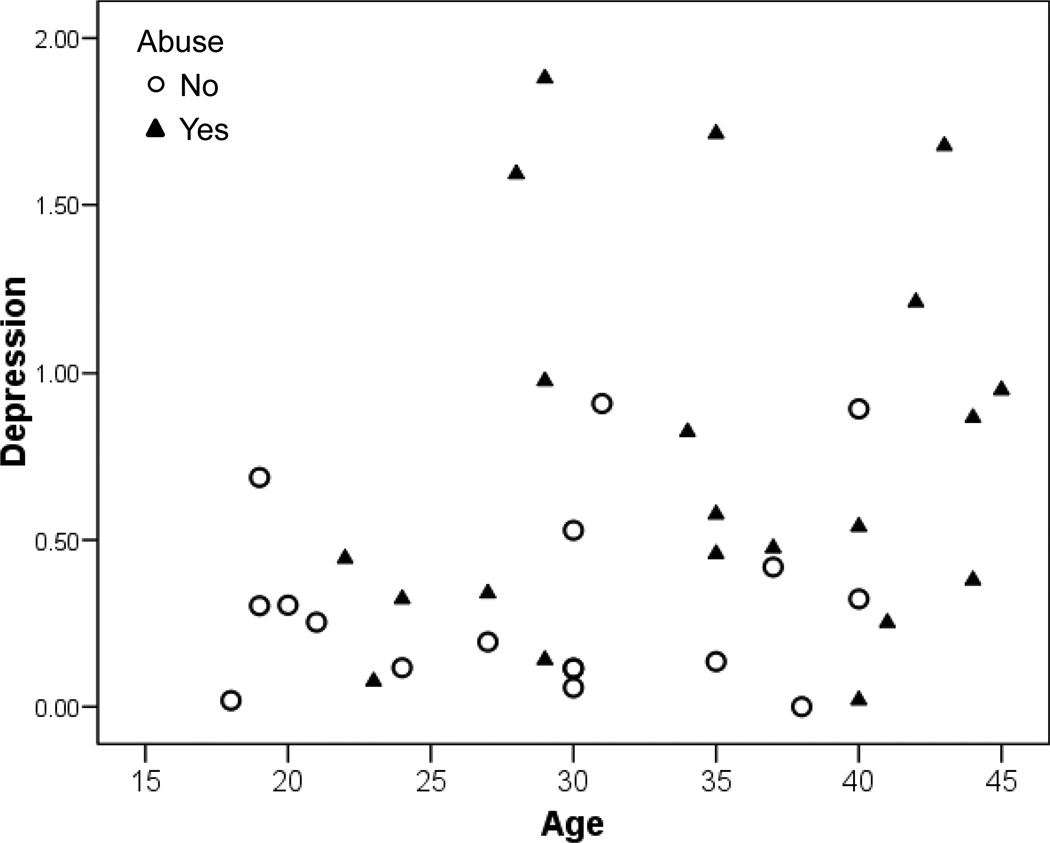

Women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group reported significantly higher levels of the somatic symptom score, though controlling for age reduces this significance. Similarly, the depression, cognitive difficulties and poor sleep scales are worse in the IBS with abuse group but the significance of this difference is greatly reduced by controlling for age. Anger is the only scale which is still significantly different after controlling for age. Figure 1 illustrates the confounding due to the age differences between the IBS without abuse/neglect and IBS with abuse/neglect groups.

Sleep Quality

Table 2 shows results on sleep quality, as measured both subjectively by self-report on the PSQI and objectively by PSG on the second night in the sleep lab. Similar to the sleep scale from the diary, women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group reported worse sleep on the PSQI. The PSQI global score becomes non-significant when age is controlled for; however, when dichotomized using either 5 or 6 as the cutpoint the elevated prevalence of poor sleep in the IBS with abuse/neglect groups remains significant even after controlling for age.

Table 2.

Objective and Subjective Sleep Variables in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome – with and without a History of Childhood Abuse and/or Neglect (mean ± SD)

| Sleep Variables | Comparison No-Abuse/ Neglect |

IBS No-Abuse/ Neglect |

IBS-Abuse/ Neglect |

P1 | P2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective sleep | n = 28 | n = 17 | n = 20 | ||

| Time in bed | 448 ± 50 | 463 ± 48 | 444 ± 49 | .251 | .380 |

| Total sleep time | 398 ± 54 | 409 ± 45 | 392 ± 53 | .289 | .640 |

| Sleep efficiency index | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.89 ± 0.06 | 0.88 0.05 | .829 | .581 |

| Sleep period efficiency index | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | .535 | .769 |

| Fragmentation index | 7.0 ± 2.2 | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 2.5 | .413 | .863 |

| Onset latency to stage 2 | 18.2 ± 17.4 | 22.3 ± 15.9 | 16.8 ± 12.0 | .239 | .390 |

| % time stage 0 & 1 | 15.5 ± 6.7 | 15.0 ± 6.6 | 16.5 ± 7.3 | .523 | .876 |

| % time stage 2 | 46.4 ± 6.0 | 47.2 ± 7.0 | 46.3 ± 9.0 | .733 | .778 |

| % time slow wave sleep | 16.9 ± 8.4 | 17.3 ± 6.3 | 13.9 ± 6.4 | .112 | .416 |

| % time in REM | 21.1 ± 3.7 | 20.4 ± 3.4 | 23.2 ± 3.9 | .026 | .032 |

| Subjective sleep | n = 32 | n = 19 | n = 21 | ||

| PSQI global | 4.00 ± 1.7 | 5.00 ± 4.0 | 7.2 ± 2.8 | .049 | .087 |

| PSQI global ≥5, n(%) | 13 (41%) | 8 (42%) | 18 (86%) | .007 | .012 |

| PSQI global ≥6, n(%) | 4 (12%) | 5 (26%) | 17 (81%) | .001 | .002 |

Note. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

P1 = unadjusted p-value, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only. P2 = p-value controlling for age, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only.

In contrast to the subjective reports of sleep quality, there is little difference between the IBS with abuse and the IBS without abuse/neglect groups on objectively measured sleep quality. The one exception is percent of time in REM sleep, which is higher in IBS with abuse.

Sleep PSG

In contrast to the subjective reports of sleep quality, there is little difference between the IBS with abuse/neglect and the IBS without abuse/neglect groups on objectively measured sleep quality. The one exception is percent of time in REM sleep, which is higher in IBS with abuse/neglect.

Heart Rate Variability

Women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group had higher nighttime heart rates (reduced RR intervals) when compared to those in the IBS without abuse group (Table 3). There was a trend for select indices of vagal modulation (LnRMSSD and LnSD5min) to be reduced in women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group as compared to those in the IBS without abuse group.

Table 3.

Comparison of Heart Rate Variability Indices in Controls and Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with and without a History of Childhood Abuse and/or Neglect (mean ± SD)

| Comparison No Abuse/Neglect n = 28 |

IBS No-Abuse/ Neglect n = 17 |

IBS-Abuse/ Neglect n = 20 |

P1 | P2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean RR interval | 905 ± 116 | 930 ± 108 | 844 ± 119 | .028a | .071 |

| Square root LF/HF | 1.44 ± 0.62 | 1.48 ± 0.70 | 1.54 ± 0.56 | .753 | .192 |

| Ln HF | 7.40 ± 0.69 | 7.53 ± 0.72 | 7.26 ± 0.61 | .226 | .704 |

| Ln RMSSD | 3.79 ± 0.59 | 3.84 ± 0.51 | 3.47 ± 0.47 | .030 | .325 |

| Ln SD5min | 4.13 ± 0.37 | 4.20 ± 0.27 | 3.93 ± 0.32 | .008 | .089 |

| Ln SDNN | 4.47 ± 0.31 | 4.53 ± 0.24 | 4.26 ± 0.30 | .006 | .041 |

P1 = unadjusted p-value, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only. P2 = p-value controlling for age, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only.

Urine Measures

There were no significant differences in first void urinary cortisol or catecholamine levels (Table 4).

Table 4.

Urine Cortisol, Norepinephrine, Epinephrine Levels in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with and without a Childhood History of Abuse and/or Neglect (mean ± SD)

| Comparison Non-Abuse (n = 29) |

IBS Non- Abuse/Neglect (n = 19) |

IBS- Abuse/Neglect (n = 20) |

P1 | P2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol µg/mg Cr | 34.59 ± 16.33 | 27.85 ± 13.41 | 28.72 ± 14.98 | .849 | .669 |

| Norepinephrine ng/mg Cr | 19.66 ± 7.56 | 20.64 ± 8.97 | 22.06 ± 9.00 | .626 | .627 |

| Epinephrine ng/mg Cr | 1.70 ± 1.48 | 1.56 ± 0.92 | 1.57 ± 0.91 | .976 | .799 |

P1 = unadjusted p-value, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only. P2 = p-value controlling for age, comparison of IBS with abuse/neglect to IBS without abuse/neglect only.

Discussion

A history of sleep disturbances is prevalent in patients, in particular women with IBS. In this study, data from a previous study (Heitkemper et al, 2005) were re-analyzed to examine childhood abuse/neglect as important factors contributing to poor sleep quality, arousal, and symptom severity in women with IBS. In the current analysis approximately 50% of women in the IBS group reported that they had experienced some form of childhood abuse and/or neglect. This percentage of women with IBS and a history of abuse/neglect is comparable to that noted by other investigators (Chitkara et al., 2008; Drossman, 1997; Talley et al., 1998; Delvaux et al., 1997). The elevated prevalence of childhood abuse/neglect is also observed in other chronic conditions. Using the CTQ Tietjen noted that of 1348 migraineurs (88% women) 58% reported some form of childhood abuse or neglect (Tietjen et al., 2009). Thirty-one percent of this sample reported IBS as a co-morbid condition. Other conditions prevalent in adult women such as chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia are also associated with early adverse events including abuse and neglect (Latthe, Mignin, Gray, Hills, & Khan, 2006; Leserman, 2006).

Interestingly in the current study women with IBS who reported a history of childhood abuse/neglect were older than women with IBS who denied this history. This age-related difference in report of abuse is similar to the study by Tietjen in which reports of all forms of childhood abuse (emotional, physical, sexual) were greater in women with migraines above 40 years of age (Tietjen et al., 2009). Whether this is a cohort effect or whether it reflects an increase in the likelihood of reporting abuse with age is not known. In a Canadian telephone survey sample of men and women who experienced childhood sexual abuse (n = 804), Hebert and colleagues noted that while many reported experiencing a childhood sexual abuse, most had not previously disclosed or had significantly delayed disclosing the abuse (Hebert, Tourigny, Cyr, McDuff, & Joly, 2009). In that survey delayed disclosure was related to increased psychological distress. Additional studies are needed to examine the impact of abuse/neglect as well as its disclosure on the development and trajectory of chronic functional health problems.

One of the primary hypothesis of the current analysis was that women with IBS who reported a history of childhood abuse/neglect would also report higher levels of abdominal pain as well as GI discomfort symptoms (e.g., bloating) on the daily diary. This hypothesis was not supported. However, women with abuse/neglect did report more heartburn and nausea. Talley using the Olmstead County, Minnesota data base (919 respondents) found that dyspepsia and heartburn were significantly associated with abuse (survey included any abuse – childhood or adult) (Talley, 1994). The association of heartburn to history of abuse (any form) has been found in other populations as well (Van Oudenhove et al., 2008). In a laboratory study of gastric sensorimotor function in 223 (84 with a positive history of abuse) patients with functional dyspepsia, Geeraerts found that patients with a history of general and severe childhood sexual abuse had significantly lower thresholds for gastric distension measured with a barostat (Geeraerts et al., 2009). In this study, the report of heartburn and nausea by both groups of IBS patients was substantially lower relative to reports of abdominal pain and bloating. The diagnostic criteria for IBS involves the presence of abdominal pain and alterations in bowel pattern (diarrhea or constipation). As such, there may be a ceiling effect with regard to whether a history of childhood abuse can significantly influence abdominal pain or bowel symptom severity in this population.

Self reports of sleep disturbances either on the daily diary or PSQI were greater in women with IBS who self reported childhood abuse/neglect as compared to those who denied this history. The finding of difficulty getting to sleep and feeling unrefreshed upon awakening is similar to studies with other populations of patients who report childhood trauma (Abrams, Mulligan, Carleton, & Asmundson, 2008). Bader in a study of primary insomniacs found that individuals who reported high adverse childhood events on the CTQ exhibited a significantly higher number of awakenings and increased movement (measured by actigraphy) and decreased sleep efficiency (Bader et al., 2007). This is consistent with the notion that childhood trauma may lead to hyperarousal. However, in the current study despite significant differences in self report of poor sleep between IBS abuse/neglect and IBS non-abuse/neglect only an increase in percent time in REM sleep and trends in other PSG variables were noted. Previously in this sample (Heitkemper et al., 2005) we found that the primary IBS versus Control group differences in PSG variables (increased REM latency) occurred on the first night (adaptation night) in the sleep laboratory only. The current analysis suggests that differences in REM sleep persist beyond the sleep laboratory adaptation night when abuse/neglect group are compared with non-abuse/neglect subjects. The trend in decreased percent in slow wave sleep (stage 3 and 4) in the IBS abuse/neglect group was reduced when age was used as a covariate.

Gastrointestinal and other visceral and somatic complaints and their relationships to traumatic childhood experiences remain to be fully characterized in women with IBS as well as those with other functional and pathological conditions. Thurston and colleagues (Thurston et al., 2008) recently reported that hot flash severity and frequency in perimenopausal women is associated with a history of childhood abuse. There are a number of possible explanations for how early traumatic experiences may influence physiological and psychological states in adulthood. Animal studies reveal that exposure to stress during early developmental stages results in both visceral sensitivity as well as behavioral changes in adult animals (O’Mahony et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2007). Early adverse stressful events and subsequent activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may modulate developing neural pathways associated with emotional regulation, cognition, and pain perception. Videlock and colleagues (Videlock et al., 2009) who found increases in salivary cortisol in response to sigmoidoscopy in those who reported adverse childhood events (e.g., divorce, loss of a parent, abuse), however we found no differences in first void urine catecholamine and cortisol excretion in IBS with abuse/neglect as compared to IBS without abuse/neglect. This suggests that differences in cortisol or other stress-related hormones such as norepinephrine and epinephrine may vary only when the individual is challenged with a stressor. In a small study of healthy women Heim and colleagues found increased pituitary-adrenal and autonomic nervous system responses to emotional stressors in women who reported a history of sexual or physical abuse during childhood Heim et al., 2000). However, in both that study and current study, the results need to be interpreted cautiously due to sample sizes.

It has also been suggested that conditions such as IBS are associated with lower socioeconomic status which has also been linked to vulnerability to adverse childhood events including abuse (Minocha, Johnson, Abell, & Wigington, 2006). Although over half of the women in the current study had a college degree, information on childhood environmental stressors such as socioeconomic status, loss of parents and poverty were not measured. Additional early childhood events including low birth weight status and use of nasogatric suction at birth have also been identified as risk factors for the presence of IBS in adults (Rey & Talley, 2009). A case-control study design could perhaps address these issues. It is interesting to note that that majority of women over age 30 in the IBS-abuse/neglect group were unmarried and unpartnered.

Thus, for some women, IBS as well as other somatic problems may be viewed as long term implications of early childhood traumatic experiences. Women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group reported on a daily basis higher levels of cognitive distress including forgetfulness, decreased ability to concentrate, and memory problems. In this young to middle-age population these differences were only modestly affected when age was controlled. Since the presence a severe psychiatric illness was used as an exclusion criteria these results suggests that women in the IBS with abuse/neglect group found these cognitive symptoms more distressing than women with IBS and no history of abuse/neglect. There are reports that women with chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia similarly relate problems with cognitive function (memory loss, difficult to concentrate) (Leavitt & Kat, 2006; Verdejo-Garcia, Lopez-Torrecillas, Calandre, Delgado-Rodriguez, & Bechara, 2009). One challenge is to determine whether these cognitive symptoms are due to premorbid states such as mood states, chronicty of illness, and/or chronic pathophysiologic processes. A recent small sample study found decrements verbal IQs in individuals with IBS (n = 29) but larger decrements in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease compared to healthy controls (Dancey, Attree, Stuart, Wilson, & Sonnet, 2009). Again, further work is needed to clarify whether mild cognitive impairments are more prevalent in patients with chronic recurring health conditions such as IBS.

The current study revealed differences in nocturnal HRV between the two groups. However, indices of vagal tone were impacted by age. HRV and in particular vagal tone decreases in both men and women with age (Cowan, Pike, & Burr, 1994). Even in this relatively narrow age range of women increasing age was associated with reduced indices of HRV. There is evidence from prior researcher that childhood abuse is associated with autonomic dysfunction as well as post traumatic stress disorder in adults (Keary, Hughes, & Palmieri, 2009; Zucker, Samuelson, Muench, Greenberg, & Gevitz, 2009). The question remains as to whether abuse directly influences the parasympathetic nervous system during a period of development thus setting the stage for decreases in HRV across the lifespan. An alternative hypothesis would be that reductions in HRV as a result of gene-environment interactions predisposes to functional problems such as IBS. In this sample we previously demonstrated IBS bowel pattern subgroup (diarrhea versus constipation) differences in HRV as well as nocturnal blood levels of norepinephrine and epinephrine on the third night in the laboratory (Burr et al., 2009). When abuse history was controlled, HRV differences between these bowel pattern subgroups was not affected.

Clinical Implications

The higher rate of abuse and neglect reported by women IBS supports the importance of gathering information regarding the childhood adverse events in clinical settings using a sensitive and perhaps standardized method. The tool used in the current study may not be adequate to capture the range of adverse events that can happen during childhood. Understanding the context of women’s lives will also help in the exploration of gene-environment factors.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of average 4 daily depression (decreased desire to talk or move, depressed/sad or blue, hopelessness) rating for 28 days on a scale of 0 ‘not present’ to 4 ‘severe’ in women with IBS with a history of abuse/neglect (n=21) and women with IBS without this history (n=17).

Acknowledgements

Supported by a grants NIH NR01094, P30 NR04001

Abbreviations

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- PSG

polysomnography

- HRV

heart rate variability

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Quality Sleep Index

- PSNS

parasympathetic nervous system

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

References

- Abrams MP, Mulligan AD, Carleton RN, Asmundson GJ. Prevalence and correlates of sleep paralysis in adults reporting childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:737–760. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader K, Schafer V, Schenkel M, Nissen L, Kuhl HC, Schwander J. Increased nocturnal activity associated with adverse childhood experiences in patients with primary insomnia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 2007;195:588–595. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318093ed00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Burr RL, Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Jun SE, Heitkemper MM. Catecholamine and cortisol levels during sleep in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2009;21:1148–e97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;103:765–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Zhang X, Li Z, Zhang H, Xu H, Bian Z. Neonatal maternal separation enhances central sensitivity to noxious colorectal distention in rat. Brain Research. 2007;1153:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan MJ, Pike KC, Burr RL. Effects of gender and age on heart rate variability in healthy individuals and in person after sudden cardiac arrest. Journal of Electrocardiology. 1994;27(Suppl):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(94)80037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancey CP, Attree ES, Stuart G, Wilson C, Sonnet A. Words fail me: the verbal IQ deficit in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 2009;15:852–857. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux M, Denis P, Allemand H. Sexual abuse is more frequently reported by IBS patients than by patients with organic digestive diseases or controls. Results of a multicentre inquiry. French Club of Digestive Motility. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 1997;9:345–352. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA. Irritable bowel syndrome and sexual/physical abuse history. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 1997;9:327–333. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Thompson JJ, Hamish MJ, Exton MS, Orr WC. Behavioral and physiological sleep characteristics in women with irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;97:2306–2314. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts B, Van Oudenhove L, Fischler B, Vandenberghe J, Caenepeel P, Janssens J, et al. Influence of abuse history on gastric sensorimotor function in functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2009;21:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Masand PS, Krulewicz S, Peindl K, Mannelli P, Varia IM, et al. Childhood abuse and treatment response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a post-hoc analysis of a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine controlled release. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology & Clinical Therapeutics. 2009;34:79–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert M, Tourigny M, Cyr M, McDuff P, Joly J. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and timing of disclosure in a representative sample of adults from Quebec. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;54:631–636. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkemper M, Jarrett M, Burr R, Cain KC, Landis C, Lentz M, et al. Subjective and objective sleep indices in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastenterology & Motility. 2005;17:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holly L, Wegman MA, Stetler C. A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:805–812. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett M, Heitkemper M, Cain KC, Burr RL, Hertig V. Sleep disturbance influences gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestive Diseases & Sciences. 2000;45:952–959. doi: 10.1023/a:1005581226265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengard B, Pedersen NL. A population-based twin study of functional somatic syndromes. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:497–505. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keary TA, Hughes JW, Palmieri PA. Women with posttraumatic stress disorder have larger decreases in heart rate variability during stress tasks. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2009;73:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett KA. Physiological correlates of childhood abuse: chronic hyperarousal in PTSD, depression, and irritable bowel syndrome. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:799–810. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiger RE, Stein PK, Bosner MS, Rottman JN. Time domain measurements of heart rate variability. Cardiology Clinics. 1992;10:487–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klem GH, Luders HO, Jasper HH, Elger C. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology Supplement. 1999;52:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latthe P, Mignin L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2006;332:749–755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38748.697465.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt F, Kat RS. Distraction as key determinant of impaired memory in patients with fibromyalgia. Journal of Rheumatology. 2006;33:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J. Sexual abuse history: prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;67:906–915. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188405.54425.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder RG, Peladeau N, Savage D, Lancee WJ. The prevalence of childhood adversity among healthcare workers and its relationship to adult life events, distress and impairment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minocha A, Johnson WD, Abell TL, Wigington WC. Prevalence, sociodemography, and quality of life of older versus younger patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Digestive Diseases & Sciences. 2006;51:446–453. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P, Codling C, Ceolho AM, Quigley EM, et al. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: Implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S, Komada Y, Kamiya T, Shirakawa S. A pilot study of the relationship between bowel habits and sleep health by actigraphy measurement and fecal flora analysis. Journal of Physiological Anthropology. 2008;27:145–151. doi: 10.2114/jpa2.27.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ori Z, Monir G, Weiss J, Sayhouni X, Singer DH. Heart rate variability. Frequency domain analysis. Cardiology Clinics. 1992;10:499–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute: University of California; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rey E, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: novel views on epidemiology and potential risk factors. Digestive Liver Disease. 2009;41:772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert JJ, Elsenbruch S, Orr WC. Sleep-related autonomic disturbances in symptom subgroups of women with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestive Diseases & Sciences. 2006;51:2121–2127. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9305-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel BM. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Current Gastroenterology Report. 2009;11:265–269. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiasny K, Oertel WH, Trenkwalder C. Clinical symptomatology and treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep Medicine Review. 2002;6:253–265. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Is the association between irritable bowel syndrome and abuse explained by neuroticism? A population based study. Gut. 1998;42:47–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston RC, Bromberger J, Chang Y, Goldbacher E, Brown C, Cyranowski JM, et al. Childhood abuse or neglect is associated with increased vasomotor symptom reporting among midlife women. Menopause. 2008;15:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietjen GE, Brandes JL, Peterlin BL, Eloff A, Dafer RM, Stein MR, et al. Childhood maltreatment and Migraine (Part III). Association with comorbid pain conditions. Headache. 2009 Oct 21; doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01558.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, Vos R, Persoons P, Fischler B, et al. Determinants of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: gastric sensorimotor function, psychosocial factors or somatisation? Gut. 2008;57:1666–1673. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.158162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Lopez-Torrecillas F, Calandre EP, Delgado-Rodriguez A, Bechara A. Executive function and decision-making in women with fibromyalgia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2009;24:113–122. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videlock EJ, Adeyemo M, Licudine A, Hirano M, Ohnigh G, Mayer M, et al. Childhood trauma is associated with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responsiveness in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1954–1962. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker TL, Samuelson KW, Muench F, Greenberg MA, Gevitz RN. The effects or respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback on heart rate variability and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a pilot study. Applied Psychophysiological Biofeedback. 2009;34:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s10484-009-9085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]