Abstract

A unique feature of the cancer-causing mucosotropic human papillomaviruses (HPVs) is the ability of their E6 proteins to interact with a number of PDZ domain-containing cellular substrates, including the cell polarity regulators hDlg and hScrib. These interactions are essential for the ability of these viruses to induce malignant progression. Rhesus papillomaviruses (RhPV) are similar to their human counterparts in that they also cause anogenital malignancy in their host, the Rhesus Macaque. However, unlike HPV E6, the RhPV E6 has no PDZ-binding motif. We now show that such a motif is present on the RhPV E7 oncoprotein. This motif specifically confers PDZ-binding activity and directs the interaction of RhPV E7 with the cell polarity regulator Par3, which it targets for proteasome-mediated degradation. These results demonstrate an amazing evolutionary conservation of function between the RhPV and the HPV oncoproteins, where both target proteins of the same cell polarity control network, although through different components and pathways.

Keywords: papillomavirus, oncoproteins, PDZ domains, Par3

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are small double-stranded DNA viruses that cause hyperproliferative lesions in epithelial tissues, which can ultimately result in cervical cancer. Those HPV types that are associated with cervical cancer are referred to as `high risk' and they include types such as HPV-16 and HPV-18 (zur Hausen, 1996). The oncogenic activity of these viruses is mediated by the joint action of two viral oncoproteins, E6 and E7. They interact with cellular proteins that regulate the cell cycle and apoptotic pathways, leading to immortalization and cell transformation (Mantovani and Banks, 2001; Munger et al., 2001). An understanding of the contributions of each protein to the continued growth of tumour cells has largely come from transgenic mice. In these circumstances, E7 appears to be largely responsible for driving cell proliferation while E6 enhances cell survival and malignancy (Song et al., 2000; Nguyen et al., 2003b).

A unique feature of the high-risk HPV E6 proteins is their ability to interact with PDZ domain-containing cellular proteins through a short motif located at their extreme carboxy-termini (Kiyono et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1997). The E6 proteins from low-risk HPV types, which cause benign lesions, lack this motif and it can therefore be considered as a molecular signature for cancer-causing mucosal HPV types. Indeed, an intact PDZ-binding site on E6 is important for inducing enhanced proliferation and transformation of primary human keratinocytes (Watson et al., 2003; Lee and Laimins, 2004) and epithelial hyperplasia in transgenic mice (Nguyen et al., 2003a). Well-characterized PDZ domain-containing targets of high-risk E6 include hDlg and hScrib (Lee et al., 1997; Nakagawa and Huibregtse, 2000), which are classified as potential tumor suppressor proteins regulating cell polarity and proliferation (Humbert et al., 2003).

Rhesus macaques (Maccaca mulatta) are the only species except humans in which mucosal PVs cause cervical neoplasia (Wood et al., 2007). Rhesus papillomavirus type 1 (RhPV-1) is closely related to HPV-16 (Ostrow et al., 1991): its sexual transmission and disease development resemble high-risk HPV infection in all major characteristics. However, unlike HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6, the RhPV-1 E6 has no PDZ-binding motif. We therefore investigated whether any alternative pathways might have evolved and we show that a PDZ-binding motif is, in fact, present on the carboxy terminus of RhPV-1 E7. The motif (A-S-R-V) corresponds to the canonical class I PDZ-binding consensus sequence (X-T/S-X-L/V). Intriguingly, this site directs the interaction of RhPV-1 E7 with Par3, a cell polarity regulator belonging to the same pathway of regulation as hScrib and hDlg.

Results

RhPV-1 E7 has a functional PDZ-binding domain

As RhPV-1 has been proposed to be a model for HPV-induced malignancy, we were interested to know whether RhPV-1 E6, like HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6, contains a PDZ-binding motif. As can be seen from Figure 1, no such motif exists in RhPV-1 E6. However, the RhPV-1 E7 carboxy-terminal sequence resembles a class I PDZ-binding site (Figure 1). To determine whether this is a true PDZ-recognition motif, we investigated whether RhPV-1 E7 could bind a panel of known PDZ domain-containing targets of HPV-18 E6. The wild-type RhPV-1 E7 plus carboxy-terminal V→A and ΔPDZ mutants, which should destroy the PDZ-binding site (Figure 1), were expressed as Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins and incubated with in vitro translated, radiolabeled hScrib, MAGI-2 and MAGI-3. The results of the pull-down assays in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1, show that wild-type RhPV-1 E7 can interact with MAGI-2, MAGI-3 and hScrib, albeit not as strongly as HPV-18 E6, while the RhPV-1 E7 V→A and ΔPDZ mutants show much weaker interactions. These results demonstrate that the carboxy-terminus of RhPV-1 E7 is a recognition motif for three different PDZ domain-containing substrates.

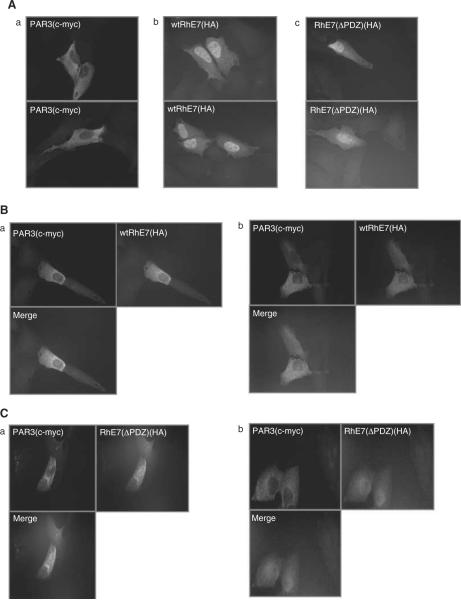

Figure 1.

The carboxy-terminal PDZ-binding motif is common to high-risk mucosal papillomavirus (PV) proteins. The PDZ-binding motif (X-T/S-X-V/L) is absent from low-risk mucosal HPV type E6s and from RhPV-1 E6. It is found at the carboxy-terminus of high-risk HPV E6s and RhPV-1 E7.

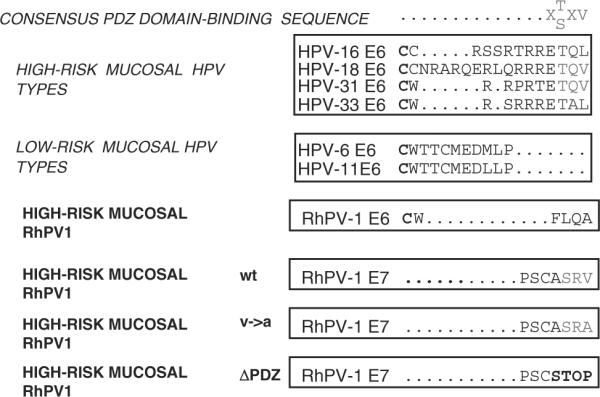

Figure 2.

RhPV-1 E7 binds to MAGI-2, MAGI-3 and Scribble. In vitro-translated MAGI-2, MAGI-3 and Scribble were incubated with GST, GST-RhPV-1 E7, GST-RhPV-1 E7 (V→A) and GST-HPV-18 E6 fusion proteins. The protein inputs are shown (MAGI-2 17%, MAGI-3 25%, Scribble 17%). Bound protein was assessed by autoradiography and input GST fusion proteins were visualized by Coomassie staining (lower panels).

These results indicate that RhPV-1 E7 has PDZ-binding potential, but that it is different from HPV-18 E6. To investigate this further we did pull-down assays using expression constructs of MAGI-3 that had been used to map the PDZ domain recognized by HPV-18 E6 (Thomas et al., 2002). The results in Supplementary Figure 2 confirm that HPV-18 E6 binds MAGI-3 PDZ1. In contrast, RhPV-1 E7 binding to MAGI-3 is weaker, and it depends upon an intact PDZ-recognition motif, and multiple PDZ domains are recognized.

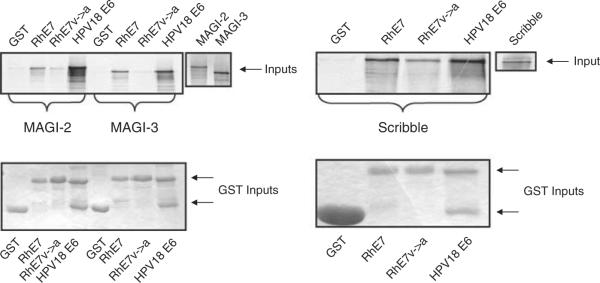

Par3 is a target of RhPV-1 E7

The degeneracy in PDZ domain recognition by RhPV-1 E7 coupled with its weaker binding characteristics, led us to conclude that these substrates of HPV-18 E6 were unlikely to be strong substrates for RhPV-1 E7 in vivo. To identify preferred cellular PDZ substrates of RhPV-1 E7, human 293 cells were transfected with a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged RhPV-1 E7 expression construct. After 24 h extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and the complex subjected to mass spectrometric analysis. Of a number of potential E7 binding partners, the only cellular PDZ-containing protein found was identified as Par3. This was intriguing as Par3 functions in the regulation of cell polarity upstream of the HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 targets, hDlg and hScrib (Humbert et al., 2006). To investigate this further, we analysed the potential of RhPV-1 to interact with Par3 in vitro. Par3 was translated then incubated with RhPV-1 GST-E7, plus HPV-18 E6 for comparison. The result of the assay in Figure 3 shows that RhPV-1 E7 binding to Par3 is much greater than that of HPV-18 E6. A single amino acid substitution in the PDZ-consensus motif greatly reduces E7 binding to Par3 and this is reduced to almost background levels if the whole PDZ-binding domain is deleted. These results demonstrate that RhPV-1 E7 binds Par3 primarily in a PDZ-dependent manner.

Figure 3.

RhPV-1 E7 protein binds to Par3 via its PDZ-binding domain. In vitro-translated Par3 was incubated with GST, wild-type and mutant GST-RhPV-1 E7, and GST-HPV-18 E6. Bound proteins were assessed by autoradiography and the input GST fusion proteins were visualized with Coomassie staining (lower panel). Input of Par3 is also shown. The numbers above each lane show the mean percentage of Par3 bound (with standard deviations) from at least three independent experiments.

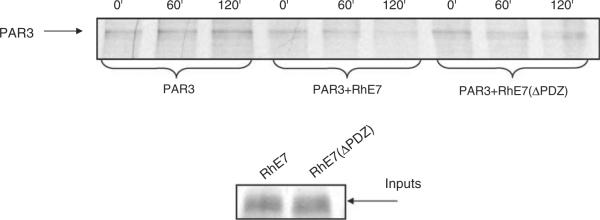

RhPV-1 E7 directs Par3 degradation

A characteristic of the HPV E6–PDZ interaction is substrate degradation (Gardiol et al., 1999; Nakagawa and Huibregtse, 2000). We wished to investigate whether RhPV-1 E7 could likewise target the degradation of Par3. To do this E7 and Par3 were translated in vitro and co-incubated at 30 °C. The level of Par3 protein remaining was ascertained by SDS–PAGE and auto-radiography. The results in Figure 4 show degradation of Par3 in the presence of RhPV-1 E7, with optimal degradation observed at the 2 h time point. This activity is much weaker with the ΔPDZ mutant of E7, demonstrating that this is also largely PDZ dependent. However, a weak degradative activity is still observed, which is consistent with the low level of interaction still seen between the ΔPDZ mutant and Par3 (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

RhPV-1 E7 directs the degradation of Par3 in vitro. Par3, RhPV-1 E7 and the ΔPDZ mutant were translated, and co-incubated at 30 °C for the times indicated. Residual Par3 was then detected by immunoprecipitation, SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. PhosphoImager quantitation of triplicate assays provides the mean (with standard deviations) percentage degradation by wild-type E7 of 32.3% (±14.2) at 60 min and 64.9% (±2.9) at 120 min with the ΔPDZ mutant degrading Par3 by 20.5% (±1.8) at 60 min and 23.5% (±2.3) at 120 min.

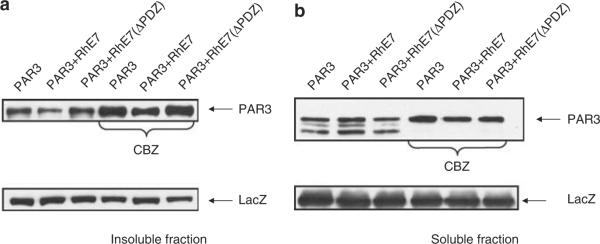

To investigate whether RhPV-1 E7 could degrade Par3 in vivo, human 293 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Par3 plus wild-type or mutant RhPV-1 E7. After 24 h the cells were harvested and Par3 levels analysed by western blotting. The results in Figure 5 show a reduction in the insoluble fraction levels of Par3 in the presence of wild-type RhPV-1 E7, part of which is due to an accumulation of Par3 in the soluble fraction. Interestingly, Par3 is unaffected by the ΔPDZ mutant, and the reduction in Par3 levels is partly proteasome dependent.

Figure 5.

RhPV-1 E7 protein enhances degradation of Par3 via the proteasome pathway. 293 cells were transfected with 1 μg Myc-tagged Par3 plus pCDNA3 (−) or plasmids expressing RhPV-1 E7 and the ΔPDZ mutant as indicated. After 24 h cells were incubated for 3 h with or without proteasome inhibitor (CBZ), before harvesting. Residual Par3 protein levels in the soluble (a) and insoluble (b) fractions were assessed by western blot analysis using anti-Myc antibody. The expression of β-galactosidase (LacZ) was used as a control for transfection efficiency and loading (lower panel). Scanning of multiple assays in the absence of CBZ treatment (in relation to the LacZ control) shows a mean change in Par3 levels in the soluble fraction of a 67% (±18.8) reduction in the presence of wild-type E7 and an 11.8% (±10.2) reduction in the presence of the ΔPDZ mutant. In the insoluble fraction the mean change in Par3 levels are a 50.3% (±8.3) increase with the wild-type E7 and an 11% (±10.8) increase with the ΔPDZ mutant.

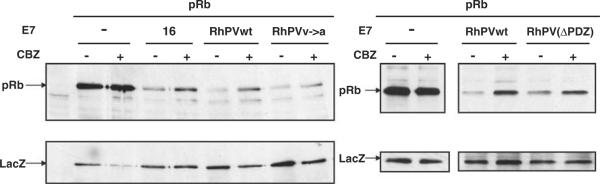

As a major target of HPV-16 E7 is the pRb tumour suppressor, we wanted to determine whether RhPV-1 E7 could likewise target pRb for degradation. Saos-2 cells were transfected with the appropriate expression plasmids and the levels of pRb expression were ascertained by western blotting. The results in Figure 6 show that RhPV-1 E7 targets pRb for proteasome-mediated degradation, similarly to that seen with HPV-16 E7. In this case the PDZ mutations in RhPV-1 E7 have no effect upon its ability to degrade pRb.

Figure 6.

RhPV-1 E7 degrades pRb via the proteasome pathway. Saos-2 cells were transfected with 3 μg pRb expression plasmid plus pCDNA3 (−) or plasmids expressing HPV-16 E7, wild-type RhPV-1 E7, the V→A and ΔPDZ mutants, as indicated. After 24 h cells were incubated for 3 h with (+) or without (−) CBZ, before harvesting. Residual pRb levels were ascertained by western blotting using anti-pRb antibody. The expression of LacZ was used as a control for transfection efficiency and loading (lower panel).

Previous studies have shown that RhPV-1 E7 can cooperate with EJ-ras in the transformation of primary BRK cells, an activity that is probably dependent upon the LxCxE motif (Ostrow et al., 1993). However, we wanted to know whether the PDZ-binding potential of RhPV-1 E7 could play a role in transformation. Therefore, co-transformation assays were performed in BRK cells using wild-type E7 or the ΔPDZ mutant together with EJ-ras. The results in Table 1 show that wild-type RhPV-1 E7 cooperates with EJ-ras at a level similar to that seen with HPV-16 E7. In contrast, the ΔPDZ mutant shows reduced levels of transforming activity, suggesting that an intact PDZ-binding motif is required for the full transforming activity of RhPV-1 E7.

Table 1.

BRK transformation assays

| Constructs | Number of transformed colonies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 | Experiment 4 | |

| RhPV-1 E7 + EJ-ras | 32 | 38 | 22 | 8 |

| RhPV-1 E7 (ΔPDZ) + EJ-ras | 15 | 18 | 3 | 0 |

| HPV-16 E7 + EJ-ras | 50 | 72 | 58 | 48 |

| EJ-ras alone | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

BRK cells from nine-day-old Wistar rats were transfected with 2 μg EJ-ras either alone or together with 5 μg HPV-16 E7, RhPV-1 E7 or RhPV-1 E7 (ΔPDZ) expression plasmids. Cells were maintained in medium containing 200 μg/ml G418 for 2 weeks and then fixed and stained. Morphologically transformed colony numbers from four independent experiments are shown.

RhPV-1 E7 and Par3 Co-localize

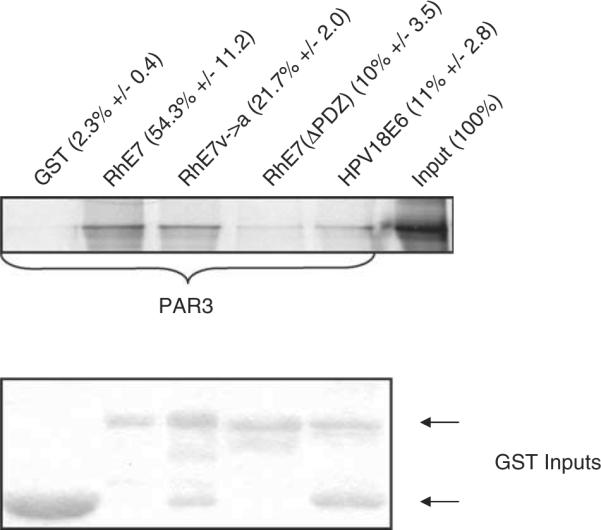

Par3 is primarily expressed at sites of cell contact and in the cytoplasm (Joberty et al., 2000), while we would expect RhPV-1 E7 to be predominantly nuclear. To determine whether specific pools of either protein could co-localize, U2OS cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Myc-tagged Par3 either alone or with HA-tagged wild-type and ΔPDZ RhPV-1 E7. After 24 h the expression of each protein was assessed by immunofluorescence. The results in Figure 7A show that Par3 is largely cytoplasmic while both wild-type and ΔPDZ E7 show nuclear and cytoplasmic expression. Upon co-transfection with Par3, however, wild-type E7 is redistributed to the cytoplasm (Figures 7B(a) and (b)), while the ΔPDZ mutant is largely unaffected (Figures 7C(a) and (b)). These results demonstrate that E7 and Par3 can co-localize, that this is pronounced when E7 and Par3 are co-expressed, and that this depends in part upon an intact PDZ motif in E7.

Figure 7.

Co-localization of RhPV-1 E7 and Par3. U2OS cells were transfected with 1 μg c-myc-tagged Par3, 2 μg HA-tagged wild-type (wt) or mutant RhPV-1 E7, alone or in combination. After 24 h, cells were fixed and probed with mouse anti-c-myc and rabbit anti-HA antibodies, followed by Rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse (red, for Par3) and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (green for RhPV-1 E7) antibodies. The slides were scanned with a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope. (A) Par 3 alone (a), wt E7 alone (b) and mutant E7 alone (c). (B) Par3 plus wt E7 (fields a and b). (C) Par3 plus mutant E7 (fields a and b). For color figure, see online version.

Discussion

PDZ domain recognition is a true molecular signature of E6 proteins derived from cervical cancer-causing HPVs. In Rhesus Macaques, RhPV-1 also causes cervical cancer, but the E6 protein has no PDZ-binding motif. However, we now show a remarkable evolutionary conservation of PDZ-binding activity on the RhPV-1 E7 protein instead. Intriguingly, this directs the binding of E7 to Par3, a protein controlling the same polarity regulation pathway as that controlled by hDlg and hScrib, the preferred PDZ domain-containing targets of HPV-18 and HPV-16 E6, respectively. These studies thus provide compelling evidence for a direct functional role for the inactivation of this pathway in the development of cervical cancer.

HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 degradation of a number of PDZ domain-containing targets contributes to these viruses' ability to induce malignancy. Lack of a PDZ-recognition motif on RhPV-1 E6 was a concern since this virus induces equivalent malignancies in its natural host. However, the finding that the RhPV-1 E7 protein has such a motif resolves this issue. In several assays we show that the carboxy-terminal four amino acids of the RhPV-1 E7 protein form a PDZ-recognition site. Using a single point mutation or deletion of the entire motif abolished PDZ recognition. However, the ability of RhPV-1 E7 to bind PDZ domains was different from that of HPV-18 E6, with respect both to the precise PDZ domains recognized as well as to the strength of the interactions. This is not surprising when one considers that the actual PDZ-binding motifs are different, even though the consensus sequence is conserved, and this would be expected to alter substrate recognition (Zhang et al., 2007). A role for this motif in the biological function of RhPV-1 E7 was shown by its requirement for optimal co-transforming activity. Previous studies had shown that RhPV-1 E7 can cooperate with EJ-ras to transform primary BRK cells (Ostrow et al., 1993), which is expected since RhPV-1 E7 retains the DLxCxE pRb recognition site (Ostrow et al., 1991). However, we found that the RhPV-1 ΔPDZE7 mutant has weaker co-transforming activity, suggesting that the ability to target one or more PDZ domain-containing substrates contributes to the ability of RhPV-1 E7 to bring about cell transformation.

Because of the differences between RhPV-1 E7 and HPV-18 E6, we attempted to identify the preferred PDZ-containing substrate of RhPV-1 E7. Using a proteomic approach we identified Par3 as a candidate interacting protein, whose association with RhPV-1 E7 is PDZ dependent. As expected from differences in the PDZ motifs, the association of RhPV-1 E7 or HPV-18 E6 with Par3 differs significantly, with E6 interacting only weakly. A striking feature of the HPV E6 and E7 proteins is their ability to direct the degradation of some of their cellular targets (Mantovani and Banks, 2001; Munger et al., 2001). Like HPV-16 E7, RhPV-1 E7 can degrade pRb. A much more intriguing finding was that RhPV-1 could target Par3 for proteasome-mediated degradation in a PDZ-dependent manner both in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism by which RhPV-1 E7 degrades Par3 is currently unknown however, the fact that this activity is readily detectable in an in vitro assay suggests that it is quite different from that used for the degradation of pRb, which is extremely difficult to recapitulate in vitro (V Tomaić, personal observation).

An important concern was whether E7 could be found in similar cellular locations to those expected for Par3 (Joberty et al., 2000). Immunofluorescent analysis showed that RhPV-1 E7 is in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments, while Par3 is mainly cytoplasmic. Interestingly, when HA-tagged RhPV-1 E7 is co-expressed with Par3 there is a clear co-localization of both proteins, with an apparent recruitment of E7 from the nucleus into the cytoplasm. This absolutely depends upon an intact PDZ-recognition motif, further supporting its role in Par3 recognition. It is notable that these studies were done using HA-tagged E7, where no degradation of Par3 is seen, and this is an important similarity with HPV-16 E7, which also requires a free N-terminal region to direct substrate proteins for proteasome-mediated degradation (Reinstein et al., 2000).

The most intriguing finding of this study is that RhPV-1 E7 targets Par3. The regulation of cell polarity and directional cell migration involves three different protein complexes: the Crumbs complex, comprising Crumbs and Stardust; the Par complex, comprising Par3, Par6, Cdc42 and aPKC; and the Scribble complex, comprising Dlg, Scrib and Lgl. Each component of these complexes is essential for the proper functioning of the whole (Humbert et al., 2006). The three complexes spatially segregate and are functionally antagonistic, restricting each other's precise cellular localization in different ways, depending on the cellular context (Humbert et al., 2006). In the case of cancer-causing mucosal HPV types, the E6 oncoproteins direct the degradation of hScrib and hDlg, and thereby induce alterations in cell migration and proliferation control (Nakagawa and Huibregtse, 2000; Watson et al., 2003). RhPV-1, which causes the same cancer, targets the same pathway albeit through a different component of the complex, Par3, but via a conserved PDZ-recognition motif. This evolutionary conservation is a very powerful argument for a critical role of the Crumbs/Par/Scrib complex in the life cycle of mucosal HPVs and in the development of HPV-induced malignancy.

Materials and methods

Cells, transfections and antibodies

U2OS, BRK and 293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium with 10% foetal bovine serum and transfected using calcium phosphate precipitation. BRK transformation assays were done as described previously (Matlashewski et al., 1987). Antibodies used were anti-HA monoclonal (Roche, Milan, Italy) and HA-polyclonal (Santa Cruz, Milan, Italy), anti-c-myc (Santa Cruz), anti-V5 (Sigma, Milan, Italy), anti pRb (Santa Cruz) and anti-β-gal (Promega, Milan, Italy).

Plasmids

The pCA plasmid was created by inserting HA and FLAG epitopes into the multiple cloning site of pCDNA3. RhPV-1 E7 was amplified from RhPV-1 genomic DNA by PCR and ligated untagged into pCDNA3 or into pCA, to produce N-terminally tagged E7. Mutants were generated using the Gene Tailor Mutagenesis kit (Sigma). To generate GST fusion proteins, RhPV-1 E7 was cloned in pGEX-2T. Myc-tagged Par3 expression plasmid was kindly provided by Ian Macara, and the hScrib, MAGI-2 and MAGI-3 plasmids have been described previously (Thomas et al., 2002), as has the EJ-ras expression plasmid pEJ6.6 (Matlashewski et al., 1987).

Binding and degradation assays

GST pull-down assays and in vitro degradation assays were performed as described previously (Thomas et al., 1996). Quantitation of the assays was done using Phosphoimaging analysis.

Sample preparation for mass spectrometry

Cells were transfected with HA-tagged RhPV-1 E7 and after 24 h, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA conjugated agarose beads (Sigma). The proteins were then eluted directly from the affinity beads using 50 ng of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) in 20 mm diammonium phosphate pH 8.0, for 6 h at 37 °C. The supernatant was removed from the beads and the cysteines were reduced and alkylated by boiling for 2 min in the presence of 10 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (Pierce, Milan, Italy) followed by incubating with 20 mm acetaminophen (Sigma) for 1 h at 37 °C. The reactions were stopped by the addition of acetic acid (Sigma) to 0.1%. The resulting mixture was desalted using C18 Ziptips (Millipore, Milan, Italy) and lyophylized to dryness.

Mass spectrometry

Nanobore columns were constructed using Picofrit columns (NewObjective, Woburn, MA, USA) packed with 15 cm of 1.8 mm Zorbax XDB C18 particles using a homemade high-pressure column loader. The desalted samples were injected onto the nanobore column in buffer A (10% methanol/0.1% formic acid) and the column was developed with a discontinuous gradient and sprayed directly into the orifice of an LTQ ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA, USA). A cycle of one full scan (400–1700 m/z) followed by eight data-dependent MS/MS scans at 25% normalized collision energy was performed throughout the LC separation. RAW files from the LTQ were converted to mzXML files by READW (version 1.6) and searched against the Ensembl human protein database and the NCBInr Viral database using the Global Proteome Machine interfaced to the X!Tandem algorithm (version 2006.06.01.2).

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in E1A buffer (25 mm HEPES (pH 7.0), 0.1% NP-40, 250 mm NaCl), cleared by centrifugation at 13 000 r.p.m for 2 min and the supernatant (soluble fraction) and pellet (insoluble fraction) were analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blot.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

Cells were stained and fixed for immunofluorescence and appropriately tagged proteins were detected using secondary antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or Rhodamine (Molecular Probes, Milan, Italy). These were visualized with a Leica (Milan, Italy) DMLB fluorescence microscope.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro to LB and from a Public Health Service Grant from the NIH CA103645 (MAO) to MO.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- Gardiol D, Kuhne C, Glaunsinger B, Lee SS, Javier R, Banks L. Oncogenic human papillomavirus E6 proteins target the discs large tumour suppressor for proteasome-mediated degradation. Oncogene. 1999;18:5487–5496. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert P, Russell S, Richardson H. Dlg, Scribble and Lgl in cell polarity, cell proliferation and cancer. Bioessays. 2003;25:542–553. doi: 10.1002/bies.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert PO, Dow LE, Russell SM. The Scribble and Par complexes in polarity and migration: friends or foes? Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joberty G, Petersen C, Gao L, Macara IG. The cell-polarity protein Par6 links Par3 and atypical protein kinase C to Cdc42. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:531–539. doi: 10.1038/35019573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono T, Hiraiwa A, Fujita M, Hayashi Y, Akiyama T, Ishibashi M. Binding of high-risk human papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins to the human homologue of the Drosophila discs large tumor suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11612–11616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Laimins LA. Role of the PDZ domain-binding motif of the oncoprotein E6 in the pathogenesis of human papillomavirus type 31. J Virol. 2004;78:12366–12377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12366-12377.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Weiss RS, Javier RT. Binding of human virus oncoproteins to hDlg/SAP97, a mammalian homolog of the Drosophila discs large tumor suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6670–6675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani F, Banks L. The human papillomavirus E6 protein and its contribution to malignant progression. Oncogene. 2001;20:7874–7887. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlashewski G, Schneider J, Banks L, Jones N, Murray A, Crawford L. Human papillomavirus type 16 DNA cooperates with activated ras in transforming primary cells. EMBO J. 1987;6:1741–1746. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger K, Basile JR, Duensing S, Eichten A, Gonzalez SL, Grace M, et al. Biological activities and molecular targets of the human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene. 2001;20:7888–7898. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Huibregtse JM. Human scribble (Vartul) is targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation by the high-risk papillomavirus E6 proteins and the E6AP ubiquitin-protein ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8244–8253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8244-8253.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen ML, Nguyen MM, Lee D, Griep AE, Lambert PF. The PDZ ligand domain of the human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein is required for E6′s induction of epithelial hyperplasia in vivo. J Virol. 2003a;77:6957–6964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6957-6964.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MM, Nguyen ML, Caruana G, Bernstein A, Lambert PF, Griep AE. Requirement of PDZ-containing proteins for cell cycle regulation and differentiation in the mouse lens epithelium. Mol Cell Biol. 2003b;23:8970–8981. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.8970-8981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow RS, LaBresh KV, Faras AJ. Characterization of the complete RhPV 1 genomic sequence and an integration locus from a metastatic tumor. Virology. 1991;181:424–429. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90519-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow RS, Liu Z, Schneider JF, McGlennen RC, Forslund K, Faras AJ. The products of the E5, E6, or E7 open reading frames of RhPV 1 can individually transform NIH 3T3 cells or in cotransfections with activated ras can transform primary rodent epithelial cells. Virology. 1993;196:861–867. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinstein E, Scheffner M, Oren M, Ciechanover A, Schwartz A. Degradation of the E7 human papillomavirus oncoprotein by the ubiquitin-proteasome system: targeting via ubiquitination of the N-terminal residue. Oncogene. 2000;19:5944–5950. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Liem A, Miller JA, Lambert PF. Human papillomavirus types 16 E6 and E7 contribute differently to carcinogenesis. Virology. 2000;267:141–150. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Laura R, Hepner K, Guccione E, Sawyers C, Lasky L, et al. Oncogenic human papillomavirus E6 proteins target the MAGI-2 and MAGI-3 proteins for degradation. Oncogene. 2002;21:5088–5096. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Massimi P, Banks L. HPV-18 E6 inhibits p53 DNA binding activity regardless of the oligomeric state of p53 or the exact p53 recognition sequence. Oncogene. 1996;13:471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RA, Thomas M, Banks L, Roberts S. Activity of the human papillomavirus E6 PDZ-binding motif correlates with an enhanced morphological transformation of immortalized human keratinocytes. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4925–4934. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CE, Chen Z, Cline JM, Miller BE, Burk RD. Characterization and experimental transmission of an oncogenic papillomavirus in female macaques. J Virol. 2007;81:6339–6345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00233-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Dasgupta J, Ma RZ, Banks L, Thomas M, Chen XS. Structures of a human papillomavirus (HPV) E6 polypeptide bound to MAGUK proteins: mechanisms of targeting tumor suppressors by a high-risk HPV oncoprotein. J Virol. 2007;81:3618–3626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02044-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen H. Papillomavirus infections—a major cause of human cancers. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:F55–F78. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.